Abstract

As the COVID-19 pandemic wears on, its psychological, emotional, and existential toll continues to grow and indeed may now rival the physical suffering caused by the illness. Patients, caregivers, and health-care workers are particularly at risk for trauma responses and would be well served by trauma-informed care practices to minimize both immediate and long-term psychological distress. Given the significant overlap between the core tenets of trauma-informed care and accepted guidelines for the provision of quality palliative care (PC), PC teams are particularly well poised to both incorporate such practices into routine care and to argue for their integration across health systems. We outline this intersection to highlight the uniquely powerful role PC teams can play to reduce the long-term psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Words: Trauma-informed care, trauma, COVID-19, coronavirus, palliative care, transdisciplinary

Introduction

As many continue to shelter in place, physically distance, and experience loss of life and normalcy, the threat of COVID-19 is pervasive and frightening. For individuals who are COVID-19+ and require acute hospital care, information overload, disconnection, isolation, and fear of dying can overwhelm the mind and nervous system.1 Patients, caregivers, and health-care workers experiencing COVID-19 are at particularly high risk for long-term psychological distress and trauma responses.2 To mitigate the lasting effects such trauma could have on individuals and communities, a trauma-informed approach to care must be implemented broadly.

COVID-19 and Trauma

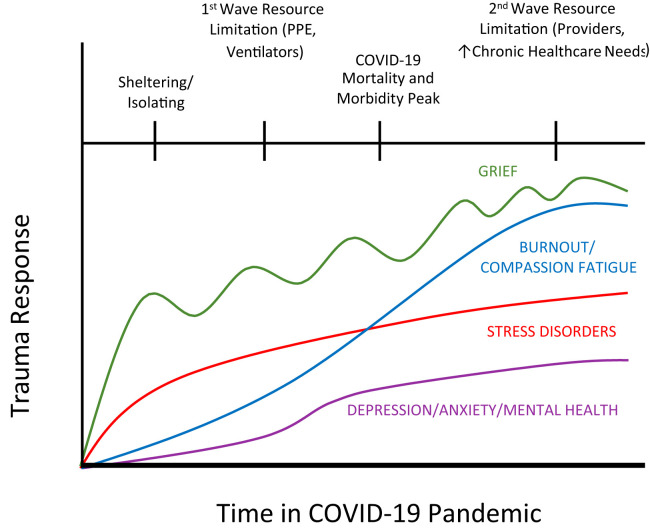

Over time, clinicians have learned how trauma manifests physically and psychologically, and how it can be exacerbated or alleviated. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association has defined trauma as resulting from “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual's functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.” 3 Recent reports of health-care workers' experiences during COVID-19 have revealed significant psychological distress related to providing care during the pandemic.4 Particularly in humanitarian crises, vicarious trauma experienced by health-care workers may result from observing suffering, caring for those dying alone, and triaging limited resources. Additional sources of psychological distress and threat to well-being for patients, caregivers, and providers may include isolation, illness stigmatization, and concern for spreading the threat of COVID-19 to others.4 After the immediate damage of COVID-19, we expect an increasing wave of trauma response from patients, caregivers, and providers alike4 (Figure 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Anticipated trauma responses during the COVID-19 pandemic. This figure is a representation of an example population response to trauma. Response rates are expected to vary by population and community. PPE = personal protective equipment.

The health-care setting poses unique risk for distress given the complex, invasive, and repetitive nature of traumatic exposure in this environment. Growing research demonstrates that traumatic experiences can lead to a variety of responses down the line, including complicated grief, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, and physical illness.5 Recognizing this risk, mental health experts and organizations such as Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Association subsequently developed a framework of “trauma-informed care” (TIC) to prevent and treat trauma responses.6

TIC in Health-Care

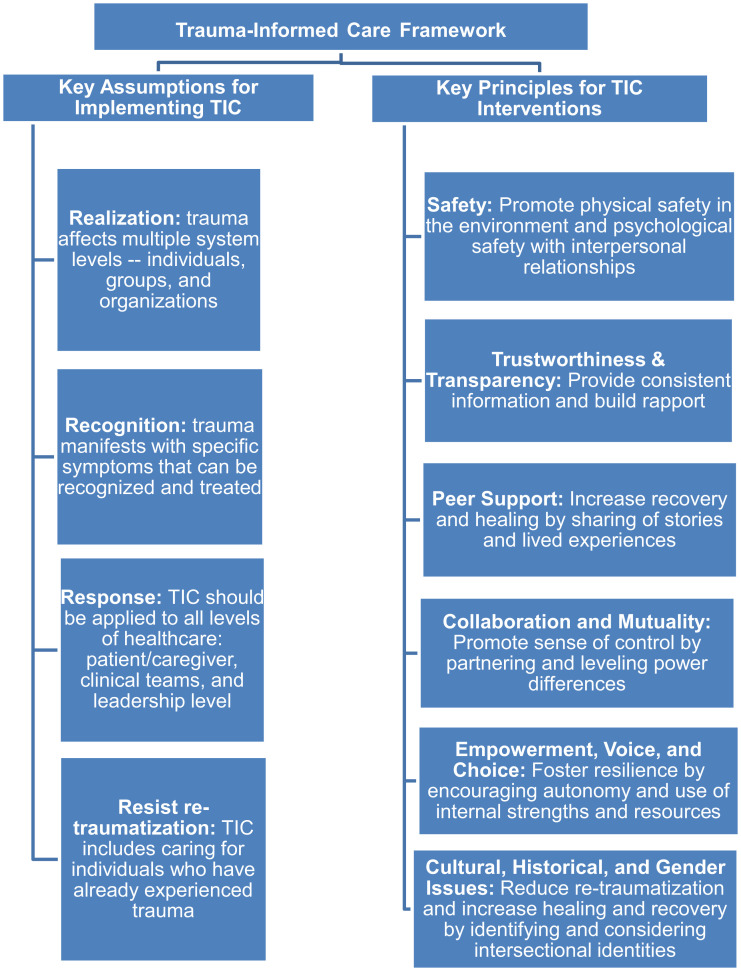

TIC adheres to four basic assumptions about trauma and integrates six essential TIC principles into patient care and organizational efforts (Figure 2 ).3 These essential assumptions and principles create a framework of care that should encompass multiple system levels—the patient and caregiver, health-care teams, and leadership across the larger health-care system—to be most effective at managing and preventing trauma system-wide.6 In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, TIC in health care has become increasingly essential.

Fig. 2.

Trauma-informed care (TIC) framework.3

Palliative Care and TIC

Palliative care (PC) teams are one of the only clinical services that extend beyond caring for patients and caregivers to supporting primary teams on the front line and interfacing with leaders who oversee the health system, making them well positioned to model this TIC framework during the COVID-19 pandemic. Owing to their transdisciplinary nature, PC teams are also well prepared to address the complex physical, psychological, and spiritual aspects of trauma that arise when caring for patients, caregivers, and primary health-care teams.

In 2018, The National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care7 disseminated the fourth edition of the Clinical Practice Guidelines, which outline core interventions for patients, caregivers, interdisciplinary teams, and health-care advocacy at the leadership level. The overlap between the NCP guidelines and TIC principles is significant and outlined in the sections that follow to further highlight how uniquely suited PC teams are to implement this care model. In addition, Table 1 provides specific examples of the many and varied trauma-informed PC interventions that teams could adopt during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1.

Examples of Trauma-Informed PC Interventions for the COVID-19 Pandemic Stratified by TIC Principle and Health System Level

| TIC Principle3 | PC Intervention at Patient/Caregiver Level | PC Intervention at Clinical Team Level | PC Intervention at Healthcare Organizational Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical and psychological safety |

|

|

|

| Trustworthiness and transparency |

|

|

|

| Peer support |

|

|

|

| Collaboration and mutuality |

|

|

|

| Empowerment, voice, and choice |

|

|

|

| Cultural, historical, and gender issues |

|

|

|

PC = palliative care; PPE = personal protective equipment; TIC = trauma-informed care.

TIC Principle 1: Safety

The NCP guidelines recognize the importance of fostering physical and psychological safety by identifying psychological, psychiatric, social, spiritual, and existential aspects of care. This includes guidelines to assess and treat emotional and spiritual distress, current or previous trauma, ability to care for self, and basic safety concerns in the home environment. NCP guidelines also highlight the importance of understanding preferences and comfort levels related to physical contact and physical space, which may vary by culture, gender, and personal preference.7

TIC Principle 2: Trustworthiness and Transparency

To achieve trustworthiness and transparency, TIC requires consistent honest information and continuous rapport building. Several NCP guidelines promote this TIC principle by encouraging patients and providers to communicate their understanding of information and ask questions; build rapport by consistently communicating with linguistic, cultural, and health literacy specifications in mind; and appreciate how historical trauma impacts levels of trust. In addition, at a patient's end of life, PC clinicians are encouraged to communicate regularly with caregivers, especially in the final days before death. NCP guidelines also outline the importance of eliciting and “honestly addressing” hopes, fears, and expectations with ongoing communication, emphasizing the PC principle of transparency.7

TIC Principle 3: Peer Support

NPC guidelines include robust recommendations for providing emotional support to patients, caregivers, and clinicians in distress. PC teams are expected to assess patients, caregivers, and staff for distress and grief; provide education and resources; and implement interventions for peer support, particularly when considering end of life and bereavement needs. For both the health of the individual and health-care system, avoiding clinician burnout is imperative and “considered an ethical obligation in all care settings” to promote sustainability.7

TIC Principle 4: Collaboration and Mutuality

Partnering with patients and caregivers in creating tailored care plans is a central tenet of both PC practice and TIC. It is well understood in both fields that patients are the experts on their bodies, their values, and their preferred type of medical, psychological, and spiritual care. The NCP guidelines outline steps to create patient- and family-centered assessments and care plans, including guidelines for considering whether decision-making structures should be individualistic, communal, or collective. Identifying appropriate community involvement is a core tenant of TIC in treating the emotional, existential, and spiritual suffering inherent to trauma. NCP guidelines highlight the importance of collaborating with peers and teams from various professions and experiences to optimize PC, as well as mobilizing patients’ personal communities.7

TIC Principle 5: Empowerment, Voice, and Choice

TIC emphasizes the importance of promoting autonomy, internal strengths, and resilience to prevent and overcome instances of trauma. The transdisciplinary nature of PC fosters this TIC principle, emphasizing the spiritual, psychological, social, and cultural resources of patients and caregivers that can be identified, uplifted, and integrated into a PC plan to promote resilience. PC interventions incorporate these aspects of care across all domains of NCP guidelines. To encourage autonomy and individual choice, “the patient's preferences, needs, values, expectations, and goals, as well as the family's concerns, provide the foundation and framework for the palliative plan of care.”7

TIC Principle 6: Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues

The importance of cultural, historical, and gender issues is addressed across the continuum of PC in the NCP guidelines. At the patient and caregiver level, the guidelines recommend “developing a care plan that reflects patient and family culture, values, strengths, goals, and preferences” and stress that “if historical trauma was assessed, the treatment plan adopts a trauma-informed approach to develop trust.” At the health-care team and organizational levels, clinicians and teams should “work to increase awareness of their own biases and seek opportunities to learn about the provision of culturally sensitive care.” PC teams should “regularly evaluate and, if needed, modify services, policies, and procedures to maximize cultural sensitivity and reduce disparities in care.”7

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, TIC is a crucial framework that can be implemented across system levels, clinical specialties, and care settings. It was not until recently that TIC became a focus within the field of PC.8 The integration of TIC principles into the NCP guidelines for Quality PC is a demonstration of the inherent alignment between these two frameworks of care.2 , 9 By rigorously implementing these core trauma-informed interventions in our work with patients and caregivers, front-line providers, and health-care leaders, PC teams can help reduce the long-term psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

This research received no specific funding/grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Coronavirus disease 2019: stress and coping. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress- anxiety.html Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 2.Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress (CSTS) Psychological effects of quarantine during the coronavirus outbreak: what healthcare providers need to know. 2020. https://www.cstsonline.org/assets/media/documents/CSTS_FS_Psychological_Effects_Quarantine_During_Coronavirus_Outbreak_Providers.pdf Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) SAMHSA's concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. 2014. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4884.pdf Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 4.Ayanian J.Z. Mental health needs of health care workers providing frontline COVID-19 care. J Am Med Assoc, Online Health Forum. 2020. https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health-forum/fullarticle/2764228 Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Van der Kolk B.A. Penguin Books; New York, New York: 2015. The body keeps the score: brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson C., Pence D.M., Conradi L. Trauma-informed care. Encyclopedia Social Work. 2013. https://oxfordre.com/socialwork/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.001.0001/acrefore-9780199975839-e-1063?print=pdf Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020.

- 7.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th edition. 2018. https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf Available from. Accessed April 29, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Ganzel B.L. Trauma-informed hospice and palliative care. Gerontologist. 2018;58:409–419. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman D.B. Stepwise psychosocial palliative care: a new approach to the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder at the end of life. J Social Work End-of-Life Palliat Care. 2017;13:113–133. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2017.1346543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makoff E. Racial trauma: a palliative care perspective. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:577–578. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]