Abstract

It is well established that pluripotent stem cells in fetal and postnatal liver (LPCs) can differentiate into both hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. However, the signaling pathways implicated in the differentiation of LPCs are still incompletely understood. Transcription Factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy, is known to be involved in osteoblast and myeloid differentiation, but its role in lineage commitment in the liver has not been investigated. Here we show that during development and upon regeneration TFEB drives the differentiation status of murine LPCs into the progenitor/cholangiocyte lineage while inhibiting hepatocyte differentiation. Genetic interaction studies show that Sox9, a marker of precursor and biliary cells, is a direct transcriptional target of TFEB and a primary mediator of its effects on liver cell fate. In summary, our findings identify an unexplored pathway that controls liver cell lineage commitment and whose dysregulation may play a role in biliary cancer.

Subject terms: Transdifferentiation, Regeneration

The Transcription Factor EB (TFEB) is known to regulate cellular homeostasis and energy metabolism, but its role in cell fate determination in the liver is unknown. Here, the authors show that TFEB regulates the progenitor/cholangiocyte lineage and that its depletion prevents tissue recovery upon injury.

Introduction

The adult liver is the largest internal organ and provides many essential metabolic, exocrine, and endocrine functions1. Being a complex organ with several cell types, liver development involves multiple cell fate decisions. For instance, during development hepatic endoderm cells, known as hepatoblasts (HBs), differentiate into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes depending on their localization with respect to the portal vein: HBs exposed to ligands from portal venous endothelial cells differentiate into primitive ductal plate cells and then form bile ducts, whereas HBs located further away from the portal vein differentiate into hepatocytes2.

Proliferation and cell fate choice are not only restricted to the embryonic stage. Indeed, despite hepatocytes in the adult liver rarely divide, under conditions in which alterations of liver mass occurs, such as surgical removal or cell loss caused by drugs or viruses, quiescent hepatocytes become proliferative and replicate to restore full liver functional capacity3. In certain injury models, hepatocytes can transdifferentiate into ductal biliary epithelial cells (BECs) to ensure tissue regeneration4–8. However, when hepatocyte proliferation is compromised, BECs become active and subsequently differentiate into hepatocytes9,10. Liver stem/progenitor cells (LPCs) may appear in chronic liver damage when hepatocyte proliferation is compromised and differentiate in both hepatocytes and bile ducts11. In humans, LPCs are evident in pathological ductular reactions often observed in a variety of liver diseases, including fatty liver diseases12, chronic viral hepatitis13, cirrhosis14, and acute hepatic injury15. Thus, LPCs are considered potential targets for liver cell transplantation and repopulation16. However, although LPCs have capacity to differentiate into hepatocytes and biliary cells in vitro and to form hepatocyte buds repopulating the liver in vivo, their ability to participate to liver regeneration in human clinical setting is still unclear17. A specialized type of cells with both LPCs and mature hepatocytes features, called hybrid hepatocytes (HybHPs), express both SRY (sex determining region Y)-box (SOX9), a marker of LPCs, and the hepatocyte marker hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α)18. HybHPs are located at the periportal region of normal liver and are efficient in liver repair when non-centrilobular hepatocytes are damaged. Thus, it appears that liver injury triggers several regenerative responses depending on the size and the proliferative capacity of the remaining liver tissue19.

The mechanisms regulating liver cell proliferation and differentiation are highly controlled to achieve accurate tissue growth and development, and deregulation of the signaling pathways involved in liver cell differentiation can impair regeneration and trigger the development of tumors with hepatocellular and cholangio-cellular differentiation features20,21. Thus, a better understanding of the processes that control liver cell differentiation in physiological and pathological conditions may contribute to the identification of druggable targets and represent a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of liver diseases.

Transcription factor EB (TFEB) belongs to the MiT-TFE family of transcription factors, which also includes MITF, TFE3, and TFEC22. In the last decade, several studies have explored the role of TFEB in physiological settings and in response to environmental cues. TFEB was first described as essential for placental vascularization23. Subsequently, TFEB has been implicated in the expression of lysosomal and autophagic genes24,25. TFEB is phosphorylated by the mTOR kinase and participates in a lysosomal signaling mechanism that is essential for nutrient sensing and maintenance of cellular homeostasis and energy metabolism26–28. In addition, TFEB has an important role in the regulation of body metabolism in liver and muscle and in the adaptation to environmental cues (e.g. fasting, high-fat diet, exercise)29,30. Furthermore, overexpression of MiT-TFE genes has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of tumors, including renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer31–34, suggesting their involvement in cell differentiation and proliferation. Consistently, it has been reported that TFEB plays a role in osteoblast35 and myeloid36 differentiation by modulating the autophagy–lysosomal pathway. Moreover, TFE3, another member of the MiT-TFE family, was shown to be involved in stem-cell commitment by enabling ESCs to withstand differentiation condition37,38. However, a role of TFEB in cell fate determination and liver cancer has not been investigated so far.

Here we show that TFEB plays a critical role in controlling cell fate and proliferation in the mammalian liver during embryogenesis and repair. Indeed, we find that TFEB is highly expressed in LPCs and BECs and that genetic manipulation of TFEB expression in the liver alters cell lineage specification in both developing and injured adult liver. Our data identify Sox9 as one important downstream target of TFEB in hepatic cell differentiation, highlighting the importance of this pathway in liver development, regeneration, and cancer.

Results

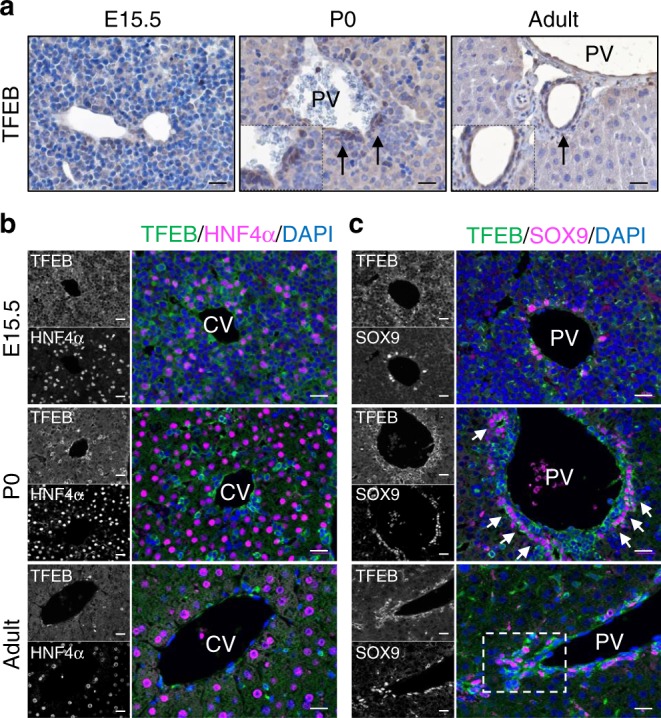

TFEB is highly expressed in the biliary compartment

To investigate whether TFEB plays a role in liver development, we examined its expression during liver specification. We used a mouse line in which the endogenous Tcfeb allele is disrupted by homologous recombination at exons 4 and 5 through the insertion of the β-galactosidase coding sequence26 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Since TcfebKO mice are embryonic lethal23,26, heterozygous embryos (TcfebLacZ/+) were collected at several embryonic stages to analyze Tcfeb promoter activity. Tcfeb expression was detected in the liver starting at embryonic stage E14.5 and increases overtime, just prior to the developmental differentiation of HBs into hepatocytes or BECs39, while no expression was detected at E12.5 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Consistent with these results, the expression of the endogenous Tcfeb mRNA and protein expression levels in fetal and neonatal livers showed a gradual increase during liver growth (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d). Immunostaining analysis revealed a dynamic expression pattern of TFEB during liver development. At E15.5 TFEB was diffuse in the entire parenchyma (Fig. 1a). At postnatal stage P0 and adult stage, a stronger expression was detected in the portal vein endothelium (Fig. 1a, b), while pericentral hepatocytes (adjacent to the central vein) showed low and diffuse TFEB expression (Fig. 1b). Indeed, TFEB was mainly detected in HNF4α−/SOX9+ ductal plate cells and mature ducts (Fig. 1b, c). X-Galactosidase staining in TcfebLacZ/+ mice showed the same pattern of expression (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Together, our results show that TFEB expression is highly enriched in progenitor/ductal cells, while mature hepatocytes display lower TFEB levels, suggesting a possible role for TFEB in liver cell fate specification.

Fig. 1. TFEB expression is enriched in ductal/progenitor cells.

a Immunohistochemistry analysis of TFEB in wild-type (WT) liver at the indicated stages showing prominent signaling in bile ductules. Arrows indicate ductal cells. b, c Representative immunofluorescence stains for TFEB/HNF4α (b) and TFEB/SOX9 (c) showing TFEB levels in the central (CV) and in the portal (PV) vein area. Scale bar 20 μm. Micrographs are representative of five mice of each stage.

TFEB influences liver cell differentiation in vitro

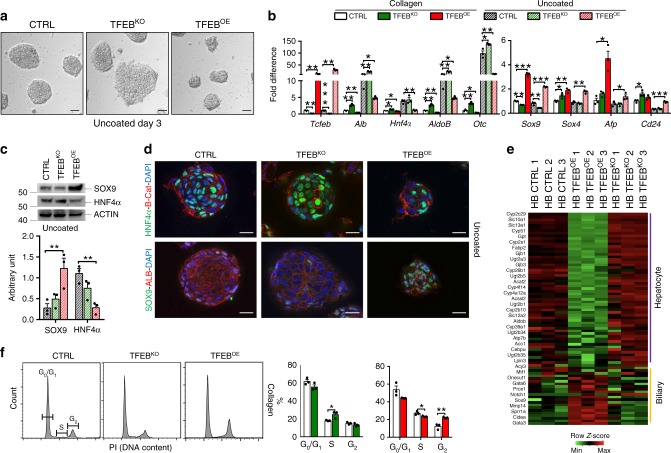

To investigate whether TFEB plays a role in liver cell commitment, we generated CRISPR/Cas9 TcfebKO (TFEBKO) (Supplementary Fig. 2a) and TFEB-overexpressing (TFEBOE) mouse HBs. To generate TFEBOE HBs, we isolated HBs from Tcfeb conditional overexpressing mice that carry Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs under the control of a strong CMV early enhancer/chicken beta-actin (CAG) promoter (Supplementary Fig. 2b)25,32. To induce Tcfeb overexpression, we infected HBs with an HDAd-BOS-CRE virus. HBs are bi-potent cells that can differentiate into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes in culture when plated on uncoated or matrigel coated plates, respectively40. Consistently, control HBs differentiated into hepatocytes forming hepatocyte clusters (Fig. 2a) and showed induction of the expression of hepatocyte-specific genes such as Alb, Hnf4α, AldoB, and Otc, with concomitant reduction of the expression of the precursor markers Sox9, Sox4, Afp, and Cd24 (Fig. 2b). Notably, HBs lacking TFEB showed significantly increased expression of the hepatocyte-specific markers and reduced Sox9 levels compared to controls, with no differences in the expression of the precursor markers Afp, Sox4, and Cd24 (Fig. 2b), suggesting that TFEB loss-of-function preferentially induces the hepatocyte differentiation program. On the contrary, TFEB-overexpressing HBs did not completely differentiate into hepatocytes, as demonstrated by the smaller size of the hepatocyte-like aggregates (Fig. 2a), lower expression levels of hepatocyte-specific genes, and higher levels of the precursor-specific markers (Fig. 2b), suggesting that TFEB overexpression prevents the hepatic differentiation of HBs, while maintaining precursor features. These results were confirmed by immunoblot and immunofluorescence analysis on HBs 3 days after hepatocytic differentiation (Fig. 2c, d).

Fig. 2. TFEB influences hepatoblast differentiation in vitro.

a Hepatocyte sphere formation of HBs of the indicated genotypes 3 days after differentiation. Scale bar 20 μm. Micrographs are representative of three independent experiments. b mRNA levels of the indicated genes were quantified by quantitative RT-PCR of total RNA isolated from control (CTRL), TFEB-overexpressing (TFEBOE), and TFEB depleted (TFEBKO) HBs undifferentiated (collagen-coated plates) or after 5 days of hepatocyte differentiation (uncoated plates). Values are indicated as mean ± SEM of n = 3 biological replicates and expressed as fold difference compared with CTRL undifferentiated HBs. c Immunoblotting analysis and relative quantification of the precursor/cholangiocyte marker SOX9 and the hepatocyte marker HNF4α in TFEBKO and TFEBOE HBs after 5 days of hepatocytic differentiation (n = 3 biological replicates). d Immunostaining for the indicated markers on TFEBKO and TFEBOE HBs 5 days after hepatocytic differentiation. Scale bar 5 μm. Micrographs are representative of three independent experiments. e Gene expression profiling of hepatocyte and biliary genes of differentiated HBs of the indicated genotypes. f Flow cytometry analysis of the cell cycle distribution of undifferentiated CTRL, TFEBKO and TFEBOE HBs and relative quantification (n = 3 biological replicates). Source data are provided in the Supplementary Fig. 10. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001 two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To confirm the defective differentiation program, we examined the effect of TFEB overexpression and depletion on the transcriptome of HBs 3 days after differentiation toward the hepatocytic lineage. Transcriptional profiles of TFEBKO and TFEBOE HBs confirmed the altered expression of hepatocyte- and progenitor/cholangiocyte-specific genes (Fig. 2e). KEGG analysis on the differentially expressed genes showed upregulation of hepatocyte-specific pathways, such as drug metabolism—cytochrome P450, fat digestion and absorption, and cholesterol metabolism in TFEBKO HBs that were instead downregulated in TFEBOE HBs (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Moreover, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) demonstrated that HNF4α targets (a master transcriptional regulator of hepatocyte differentiation) are enriched among upregulated genes in TFEBKO HBs and show a reduced expression, despite not significant, in TFEBOE HBs (Supplementary Fig. 2c). We also examined the distribution of HBs in the three phases of the cell cycle (G1 vs S vs G2/M). TFEBKO HBs showed significant increase in the percentage of S phase cells compared to controls, suggesting that TFEB depletion induces S phase arrest in HBs (Fig. 2f). Interestingly, TFEB overexpression in HBs resulted in increased percentage of cells in the G2/M phase compared with control cells with a concomitant reduction in the S phase (Fig. 2f), suggesting increased proliferation.

In contrast to the complete inhibition of hepatocyte specification, neither TFEB depletion nor overexpression impaired biliary differentiation of HBs. Indeed, TFEBKO and TFEBOE cells supported tubule formation (Supplementary Fig. 2d) and expressed biliary genes (i.e. Hif1α, Hnf6, Ggt1) after cholangiocytic differentiation despite the reduced or increased expression levels of both Sox9 and Afp, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2e).

Together these results indicate that TFEB plays a role in the lineage commitment of liver precursor cells.

TFEBOE induces a progenitor/biliary phenotype in vivo

To test whether TFEB overexpression alters cell differentiation from a progenitor state and impairs homeostasis of mature hepatocytes in vivo, we crossed the Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs mouse line (Supplementary Fig. 2b) with a transgenic line carrying Alb-Cre recombinase to obtain Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs;Alb-Cre mice (hereafter referred to as Tg). Albumin is expressed by the bipotential HB progenitors, thus enabling us to investigate the role of TFEB during liver cell specification. Tomato expression and in situ hybridization analysis confirmed TFEB overexpression in hepatocytes and BECs at E18.5, P0, and P9 (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). HB-specific expression of TFEB was assessed by qPCR analysis on liver extracts of Tg mice showing an approximately 10-fold increase of Tcfeb mRNA levels in E18.5, P0, and P9 livers and up to 65-fold in 3-month-old mice (Supplementary Fig. 3c), consistent with the progressive increase in Alb mRNA during liver specification41.

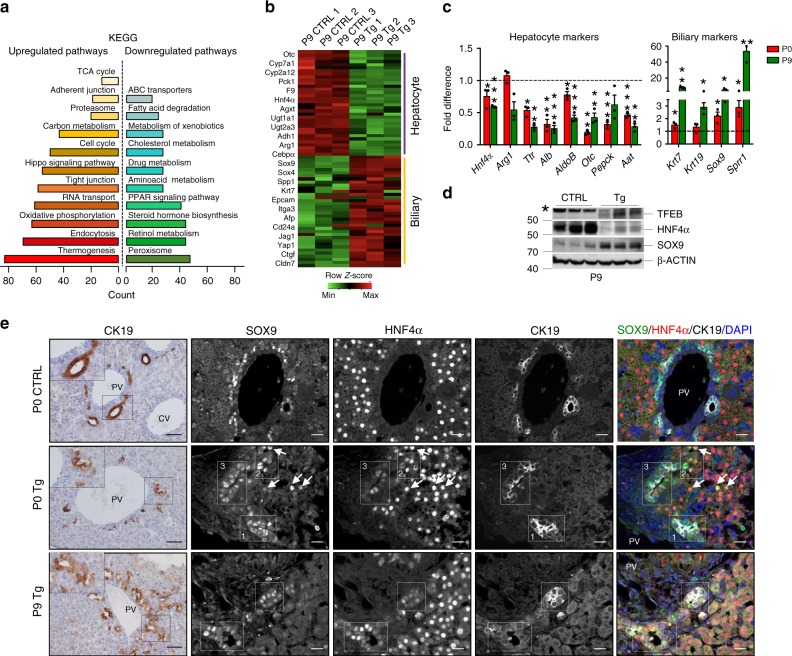

To examine the effects of TFEB overexpression in vivo, we carried out microarray analysis at an early stage (P9) showing a total of 8400 differentially expressed genes. KEGG analysis revealed that several upregulated genes are involved in oxidative phosphorylation, proteasome, cell cycle, Hippo signaling pathway and endocytosis, among others, while downregulated genes are mostly involved in hepatocyte-specific pathways, such as amino acid, cholesterol, and lipid metabolism, drug metabolism (P450), PPAR signaling pathway (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Table 3). Consistent with in vitro data, gene expression profile of Tg livers demonstrated a reduction in the expression of hepatocyte-specific genes and an increase in progenitor/cholangiocyte related genes compared with control livers (Fig. 3b, c, Supplementary Table 4). Immunoblotting analysis confirmed the reduction of HNF4α and the increase of SOX9 protein levels in liver extracts from Tg mice at P9 (Fig. 3d). Similar results were obtained in primary hepatocytes isolated from 21-day-old Tg and control mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Interestingly, while no CK19+ cells were detected in control hepatocytes, we found HNF4α+/CK19+ Tg cells, suggesting a hybrid phenotype of Tg hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Indeed, immunostaining for the cholangiocyte marker CK19 in Tg livers from P0 mice showed CK19+ cells with hepatocyte-like morphology positive for the hepatocyte marker HNF4α mainly in the periportal area (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 5a). The concomitant positive signals for both a cholangiocyte and a hepatocyte marker suggest defective differentiation. At P9, Tg mice exhibited dilated bile ducts and ectopic tubules throughout the lobule (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. 5a). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that most of the ductal CK19+ cells were positive for SOX9 (Supplementary Fig. 5b), as expected, but other cells scattered in the entire parenchyma were HNF4α+/SOX9+/CK19− in P0 and P9 livers (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig 6a), suggesting that they were hepatocytes with bi-phenotypic features. In situ hybridization analysis confirmed that SOX9 was expressed in the entire liver in Tg mice compared to controls (Supplementary Fig. 6b).

Fig. 3. TFEB overexpression inhibits hepatocyte differentiation in vivo.

a KEGG pathways enriched in upregulated and downregulated genes of P9 liver overexpressing TFEB compared to CTRL. b Heat map showing the relative fold change of hepatocyte and biliary genes. c RT-PCR analysis of hepatocyte- and cholangiocyte-specific markers in liver isolated from P0 and P9 mice (n = 3 biological replicates). The dashed line represents gene expression levels in CTRL liver. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01 two-tailed Student’s t-test compared to age-matched CTRL. d Immunoblotting analysis of TFEB, HNF4α, and SOX9 in liver extracts from mice at P9. Actin was used as a loading control. e Left panel: Representative images of liver sections from P0 and P9 mice stained for CK19. Scale bar 50 μm. Right panels: triple immunostaining for HNF4α (red), SOX9 (green), and CK19 (white) in liver sections from P0 and P9 mice of the indicated genotype showing the hybrid characteristics of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes in Tg mice. Note the cells expressing SOX9 and CK19 (box1), SOX9 and HNF4α (box2) or SOX9/HNF4α/CK19 (box3). Scale bar 20 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Together, these observations suggested that TFEB overexpression directs cell fate of HBs towards a progenitor/cholangiocyte lineage.

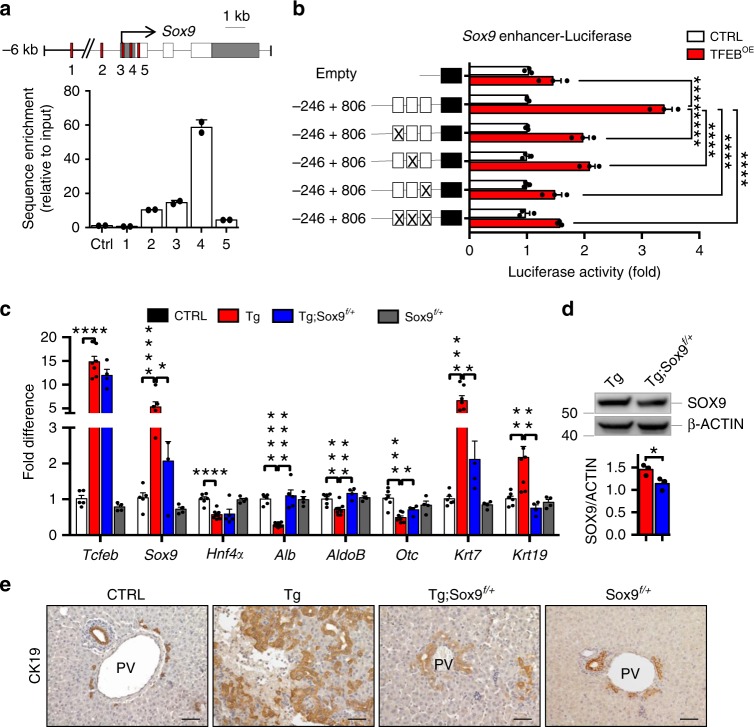

Sox9 is a direct target of TFEB

Our transcriptomic analysis in TFEBOE HBs and livers showed enrichment in several progenitor-specific genes, including Sox9. Sox9 overexpression is known to be sufficient to induce biliary genes and suppress differentiation into the hepatocyte lineage42. Therefore, we investigated whether Sox9 is a direct transcriptional target of TFEB and a mediator of TFEB effects on liver cell differentiation. We analyzed the promoter region of Sox9 gene and identified five putative TFEB target sites (i.e. the CLEAR sites)24 that were validated by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis. Compared with a control sequence, the sequences closest to the Sox9 transcriptional start site (TSS) were significantly enriched in liver samples from Tg mice (Fig. 4a). The region containing CLEAR sites closest to the TSS was cloned into a luciferase reporter plasmid to evaluate its responsiveness to TFEB in HBs. Overexpression of TFEB increased luciferase activity in HBs, whereas deletion of the CLEAR sites failed to induce transactivation (Fig. 4b). Taken together these data indicate that TFEB binds to the Sox9 promoter, identifying Sox9 as a direct transcriptional target of TFEB.

Fig. 4. TFEB directly controls Sox9 expression.

a ChIP analysis of TFEB binding to the Sox9 promoter in Tg livers. CLEAR sites in the promoter region of Sox9 are indicated by red squares. Bar graphs show the amount of immuno-precipitated DNA as detected by RT-PCR analysis. Values are representative of two independent experiments. Data were normalized to the input and plotted as relative enrichment over the control sequence. b Luciferase expression upon TFEB overexpression was measured in HBs infected with HDAd-LacZ (CTRL) or HDAd-CRE expressing viruses (TFEBOE) for 24 h and transfected with wild type or mutated Sox9-promoter luciferase reporter plasmids (n = 3 biological replicates). Deletion of the CLEAR sites resulted in reduced luciferase transactivation. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p ≤ 0.0001 two-way ANOVA. c RT-PCR expression analysis of hepatocyte- and cholangiocyte-specific markers in livers isolated from P9 mice for the indicated genotypes (n = 6 CTRL, n = 8 Tg, n = 4 Tg; Sox9f/+, n = 4 Sox9f/+). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001 two-tailed Student’s t-test. d Representative immunoblot for SOX9 in liver of the indicated genotypes and relative quantification (n = 3 biological replicates). e CK19 immunostaining of liver sections from P9 mice of the indicated genotypes. Scale bar 50 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further validate our findings, we performed genetic interaction studies by crossing Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs;Alb-Cre with Sox9f/f mice to generate double transgenic Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs;Alb-Cre;Sox9f/+ mice (hereafter Tg;Sox9f/+). The expression of Sox9 was significantly reduced in livers from Tg;Sox9f/+compared with Tg mice (Fig. 4c, d). qPCR analysis on livers from Tg;Sox9f/+ at P9 showed higher expression levels of hepatocyte-specific markers (e.g. Alb, AldoB, and Otc) and a reduction of cholangiocyte-markers (e.g. Krt7 and Krt19) compared with Tg mice (Fig. 4c). Interestingly, immunostaining analysis showed that Sox9 knockdown resulted in reduced number of CK19+ cells compared to Tg liver (Fig. 4e). These data suggest that SOX9 mediates, at least partially, the effects of TFEB on the determination of liver cell fate.

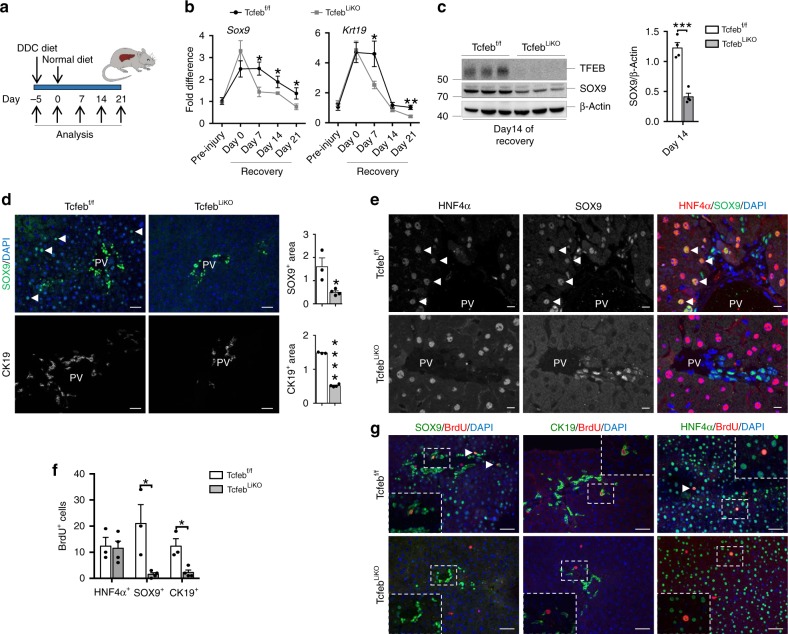

TFEB depletion impairs LPC expansion upon liver injury

We then investigated the effects of TFEB deletion on liver cell differentiation in a previously described TFEB liver-specific conditional KO mouse line Alb-Cre;Tcfebf/f (TcfebLiKO)26. While immunofluorescence analysis did not reveal any significant cell differentiation defect in TFEB-depleted livers compared to age-matched controls at P0 and 1 month (Supplementary Fig. 7), DDC-induced liver damage (Fig. 5a) in TcfebLiKO mice resulted in a reduction in the expression of Sox9 and Krt19 during the recovery phase (Fig. 5b), which was confirmed by immunoblot analysis and immunostaining for SOX9 at 14 days after recovery (Fig. 5c, d). These mice also showed a reduced ductular reaction as measured by CK19 immunostaining (Fig. 5d). Interestingly, while control livers showed hybrid hepatocytes positive for both HNF4α and SOX9 around the portal vein as a consequence of liver damage, as previously shown43, TcfebLiKO mice showed SOX9+ cells only in the portal area (Fig. 5d, e) and a strong reduction of proliferating SOX9+ and CK19+ cells, indicating impaired LPC activation (Fig. 5f, g). No main differences were observed in weight recovery after injury in the two genotypes (Supplementary Fig. 8a), while an increase in serum markers of liver damage (e.g. bilirubin and AST) was detected in TcfebLiKO mice compared to control mice (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These data suggest that liver cell differentiation after injury requires TFEB induction. Consistently, we found that TFEB translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus 7 days after recovery from DDC-induced liver injury (Supplementary Fig. 8c), a time point during which we detected a reduction in mTOR activity, as measured by detecting the phosphorylation of the mTOR substrate 4EBP1 (Supplementary Fig. 8d).

Fig. 5. TFEB depletion impairs ductular reaction and cell proliferation after liver injury.

a Experimental strategy for liver injury protocol for TFEBLiKO mice. b, c Expression levels of Sox9 and Krt19 mRNA (pre-injury n = 3, day 0–7–14–21 n = 5 biological replicates per genotype) at different time points (b) and immunoblotting with relative quantification (n = 4 biological replicates) (c) of livers isolated from TFEBf/f and TFEBLiKO mice 14 days after discontinuation of DDC food. In b, values are expressed as fold difference relative to TFEBf/f mice. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001 two-tailed Student’s t-test. d SOX9 and CK19 immunofluorescence with relative quantifications (TFEBf/f n = 3, TFEBLiKO n = 4 biological replicates/n = 5 different images/sample) of liver isolated from TFEBf/f and TFEBLiKO mice 14 days after recovery and relative quantifications. Scale bar 50 μm. e HNF4α/SOX9 dual staining of liver sections from TFEBf/f and TFEBLiKO mice. Scale bar 5 μm. f, g Quantification of BrdU+ cells (n = 3 biological replicates/n = 5 different images/sample) (f) and representative images (g). Scale bar 50 μm. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p ≤ 0.05 two-tailed Student’s t-test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

TFEBOE in regenerating adult liver subverts cell identity

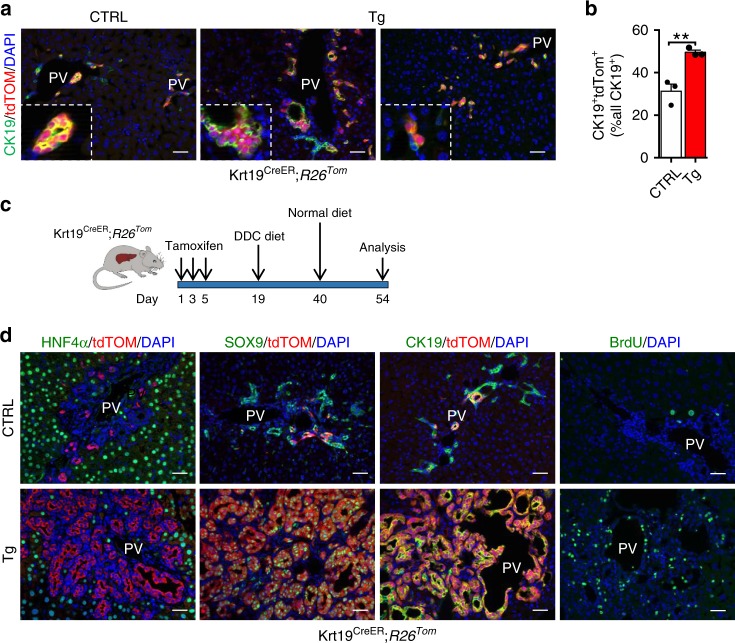

The effects of TFEB overexpression in the progenitor/cholangiocyte compartment were investigated by crossing the Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs;R26RLSLtdTomato mice with an inducible Krt19CreERT mouse line that labels the biliary epithelium with a 40% recombination efficiency (Fig. 6a, b)10. Four-weeks after tamoxifen injection, tdTom expression was observed only in biliary ducts and in small periportal ductules (Fig. 6a). Based on the results obtained in Alb-Cre mice, we hypothesized that TFEB overexpression would expand the CK19+ population in the periportal area by generating a ductal reaction. Indeed, we observed an increase in CK19+/tdTom+ cells in Tg mice compared to controls (Fig. 6b), hyperplasia of the bile ducts, and a population of cells growing within the ductal epithelium and forming multilayered structures (Fig. 6a). In addition, some of the CK19+/tdTom+ cells appeared with a rounded morphology, compared to the cuboidal biliary epithelium observed in control mice, with a migrating phenotype that mimics a ductular reaction (Fig. 6a). This phenotype strongly resembles the one observed in YAP-overexpressing biliary cells44.

Fig. 6. TFEB overexpression in progenitor/cholangiocytes gives rise to ectopic ductal structures.

a Representative image of CK19/tdTom dual immunofluorescence of CTRL and TFEBOE liver 4-weeks after tamoxifen injection. Scale bar 50 μm. b Quantification of CK19+ biliary epithelial cells that were tdTom+ (n = 3 biological replicates/n = 5 different images/sample). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. **p ≤ 0.01 two-tailed Student’s t-test. c Experimental strategy to lineage trace biliary epithelial cells on a background of liver injury. d tdTom/HNF4α, tdTom/SOX9, and tdTom/CK19 immunofluorescent images at 14 days after DDC diet. Scale bar 50 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Subsequently, to stimulate a progenitor/biliary-derived liver regenerative response, we induced chronic liver damage by feeding mice with a 0.1% 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC)-containing diet for 3 weeks and then switch to a normal diet for 14 days, a protocol causing transient LPC activation (Fig. 6c)5. Interestingly, while control mice showed tdTom+ cholangiocytes in the portal area and the expected ductular reaction as shown by tdTom, CK19 and SOX9 immunostaining (Fig. 6d), most of the CK19+ and SOX9+ cholangiocytes were tdTom+ in Tg mice, suggesting increased proliferation of the tdTom+ cells upon TFEB overexpression, as also confirmed by BrdU analysis (Fig. 6d). Notably, these mice recapitulate the same phenotype observed in the Alb-Cre;Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs mice.

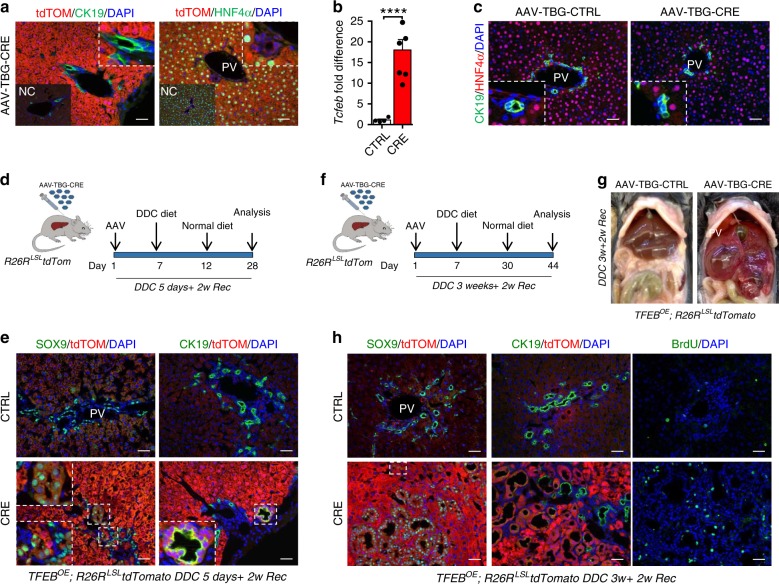

To overexpress TFEB specifically in the hepatocytes, we injected Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs;R26RLSLtdTomato mice with a CRE-expressing adeno-associated virus (AAV8-TBG-CRE). As expected, AAV8 injection induced CRE expression in 99% of the hepatocytes and no expression in the biliary cells as demonstrated by tdTom staining (Fig. 7a)5. These mice showed 20-fold increase of Tcfeb expression at 4 weeks after injection (Fig. 7b), but no alteration in cell identity compared to controls (Fig. 7c). These results suggest that TFEB overexpression in differentiated adult hepatocytes is not sufficient to induce their conversion to cholangiocytes.

Fig. 7. TFEB-overexpressing hepatocytes dedifferentiate in progenitor/cholangiocyte-like cells upon liver injury.

a tdTom/CK19 and tdTom/HNF4α immunofluorescence in AAV8-TBG-CRE-treated livers 4 weeks after injection. CRE-treated HNF4α+ hepatocytes are tdTom+ in contrast to CK19+ ductal cells located in the portal tract (PV). Insets: images of AAV-CTRL injected liver indicated as negative control (NC). Scale bar 50 μm. b Transcript levels of Tcfeb in livers isolated from AAV8-TBG-CRE-treated mice 4 weeks after injection (CTRL n = 4, CRE n = 6 biological replicates). Tcfeb mRNA levels were normalized to the CTRL. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ****p ≤ 0.0001 two-tailed Student’s t-test. c CK19/HNF4α immunofluorescence analysis in AAV8-TBG-CRE-treated and CTRL liver 4 weeks after injection showing no alteration in cell identity. Scale bar 50 μm. d Experimental design of the AAV8 injection followed by acute liver injury protocol. e Fourteen days post DDC acute injury hepatocytes dedifferentiate in progenitor/biliary cells. f Experimental design of the AAV8 injection followed by chronic liver injury protocol. g Gross appearance of AAV-injected livers from day 14 of recovery after DDC prolonged exposure. h Immunofluorescence analysis of AAV8-treated livers at day 14 of recovery after DDC diet. Scale bar 50 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To evaluate whether TFEB overexpression in hepatocytes alters cell identity upon liver injury, we fed Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs;R26RLSLtdTomato mice injected with AAV8-TBG-CTRL or AAV8-TBG-CRE with the DDC-containing diet. We first used a protocol of acute injury by feeding mice a DDC-containing diet for 5 days and switching to a normal diet for 14 days (Fig. 7d). Interestingly, CRE-injected mice showed tdTom+ hepatocytes positive for SOX9 and CK19, strongly suggesting a conversion of TFEBOE cells in progenitor/cholangiocyte-like cells upon liver damage (Fig. 7e). Notably, the chronic exposure to DDC-containing food for 3 weeks following by 14 days of recovery resulted in liver tumors in CRE-injected mice (Fig. 7f, g). Histological analysis showed that most of the CK19+/SOX9+ cells were tdTom+, and that some tdTom+ hepatocytes also expressed SOX9 (Fig. 7h), confirming that TFEB overexpression in hepatocytes leads to trans-differentiation in progenitor/cholangiocytes in conditions of liver damage when cells are more prone to proliferation and trans-differentiation.

Together our data strongly confirm that TFEB overexpression in progenitors/cholangiocytes is able to influence proliferation and differentiation.

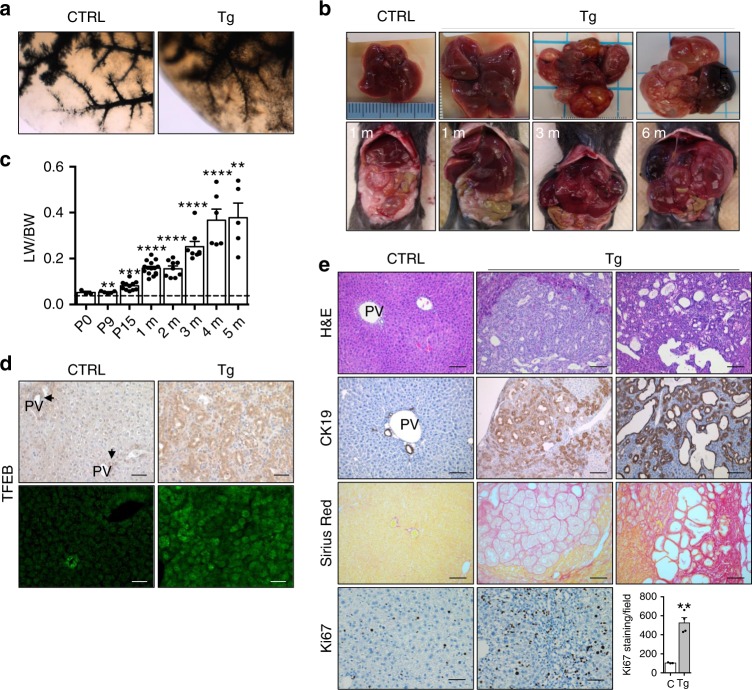

Cholangiocarcinoma-like phenotype in TFEBOE mice

We then analyzed the phenotypic consequence of the altered cell differentiation associated with TFEB overexpression in the liver. Tg mice exhibited significant hepatocellular derangement as shown by an increase of liver damage markers, as well as a significant increase in both total bilirubin and direct bilirubin at 15 days and 3 months (Supplementary Table 5) consistent with cholestasis. Serum bile acid and cholesterol levels were also increased in Tg mice compared to controls (Supplementary Table 5). Analysis of three-dimensional structure of the biliary system in adult liver, performed by retrograde injection of ink in the biliary tree in 2-month-old mice, confirmed a defect in bile duct development (Fig. 8a). Indeed, we observed reduced density of branches arising from major branches and abnormal major branches in appearance consistent with partial obstruction of bile flow, correlating with increased bilirubin and ALT levels. Furthermore, Tg mice showed a progressive increase in liver mass relative to total body mass with a 2-, 4-, and 10-fold increase at 2 weeks, 2 months, and 5 months of age, respectively (Fig. 8b, c). At 3 months, TFEB overexpression was detected in the entire parenchyma and in particular in the dilated ducts as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization analysis (Fig. 8d). Livers from Tg mice displayed variable degrees of hyperplasia of bile ducts, which were increased in size and number, and an altered morphology of epithelial cells. In addition, they showed multifocal biliary cystic hyperplasia with cysts lined by flattened epithelium at 3 months of age (Fig. 8e). Densely packed cholangiocytes, as revealed by CK19 immunostaining, associated with increased fibrosis revealed by Sirius red staining, were also detected suggesting the presence of a neoplasms of the bile ducts. All of these phenotypic features are consistent with the presence of a cholangiocarcinoma (CCA)-like phenotype. Livers from 6-month-old Tg mice showed multiple cysts replacing most of the hepatic parenchyma. At this age mice began to die or needed to be euthanized due to poor health status. Increased liver mass in Tg mice was associated with a higher proliferation index compared to control mice, as shown by increased Ki67 staining (Fig. 8e). A similar, albeit milder and with later onset, phenotype was observed in a different transgenic mouse line in which Tcfeb is overexpressed at lower levels (2.5-fold increase) suggesting a dose- and time-dependent effect of TFEB overexpression (Supplementary Fig. 9a–d).

Fig. 8. Bile duct neoplasm in TFEB-overexpressing liver.

a Retrograde injection of ink revealed abnormal development of the bile duct in Tg liver compared to control. b Gross appearance of livers in Tg mice at several ages. c Quantification of liver-to-body weight ratio (LW/BW) in Tg mice at the indicated age. (n = 3 P0, n = 5 P9, n = 11 P15, n = 15 1 month, n = 9 2 months, n = 8 3 months, n = 6 4 months, n = 5 5 months). Values were normalized to age-matched control liver as indicated by the dashed line. d Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization analysis for TFEB in CTRL and Tg liver at 3 months of age. Scale bar 50 μm. e Histological characterization of Tg liver phenotype at 3 months of age. Lower panel: Ki67 staining and relative quantification showing increased cell proliferation in Tg liver compared to CTRL (CTRL n = 3, Tg n = 4 biological replicates/n = 5 different images/sample). Data are represented as mean ± SEM. ***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001 two-tailed Student’s t-test. Scale bar 100 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

These data are consistent with a pro-cholangiocytic function of TFEB and suggest that TFEB induction may be involved in the pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma.

Discussion

Recent studies have identified an important role for MiT-TFE transcription factors (TFs) in the regulation of basic cellular processes, such as lysosome, autophagosome, and melanosome biogenesis24,25,45,46. These TFs control organismal adaptation to environmental cues, such as nutrient availability, physical exercise, and infections29,30,34,47–51. While some studies reported the involvement of MiT-TFE genes in cell differentiation, the precise role that these TFs play in cell specification and in embryonic development has remained elusive. TFEB full KO mice die at E10 due to a placental vascularization defect, indicating that embryonic development requires TFEB-mediated transcriptional control23. In addition, previous studies showed that MITF and TFEB are involved in the differentiation processes of melanocytes and osteoclasts, respectively52. A recent study also reported a role for TFEB in the activation and response to growth factor in quiescent neuronal stem cells (qNSCs)53. Furthermore, TFE3, another member of the MiT family, was shown to be involved in stem-cell commitment by enabling ESCs to withstand differentiation condition37. In the present study, we reveal an unpredicted role for TFEB in liver cell differentiation during development and in the regenerative response to injury. We found that TFEB expression levels increase overtime during liver specification. Moreover, we observed differences in the levels of TFEB expression between pericentral vs periportal area suggesting that different levels of TFEB could determine different progenitor cell fates. Indeed, our data show that TFEB mainly specify the cholangiocyte lineage. This is also supported by the finding that TFEB overexpression in HBs dictates a progenitor/cholangiocytic fate resulting in a rapid replacement of the entire liver by biliary structures. In this regard, it will be interesting to determine the mechanisms that allow the differential expression of TFEB in specific subsets of cells.

Hepatocyte identity is defined by the expression of a core group of transcription factors primarily driven by the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha (C/EBPα)54, a key hepatic transcription factor that also controls the expression of genes involved in ammonia detoxification and glucose and lipid homeostasis. Another key regulator of cell identity in the liver is SOX9, a transcription factor that drives bile duct morphogenesis and is recognized as a specific marker of precursors and biliary cells in the developing liver55. Remarkably, C/EBPα and SOX9 form a mutually antagonistic system controlling the hepatocyte versus biliary fate during normal liver homeostasis and regeneration42. Our in vitro and in vivo studies indicate that TFEB directly controls the expression of Sox9 during progenitor/ductal specification and after liver injury. Indeed, our epistatic analysis using Sox9-deficient mice provides evidence that TFEB-mediated regulation of SOX9 is required for proper differentiation of bipotential progenitors, although additional mechanisms downstream of TFEB are likely to play a role.

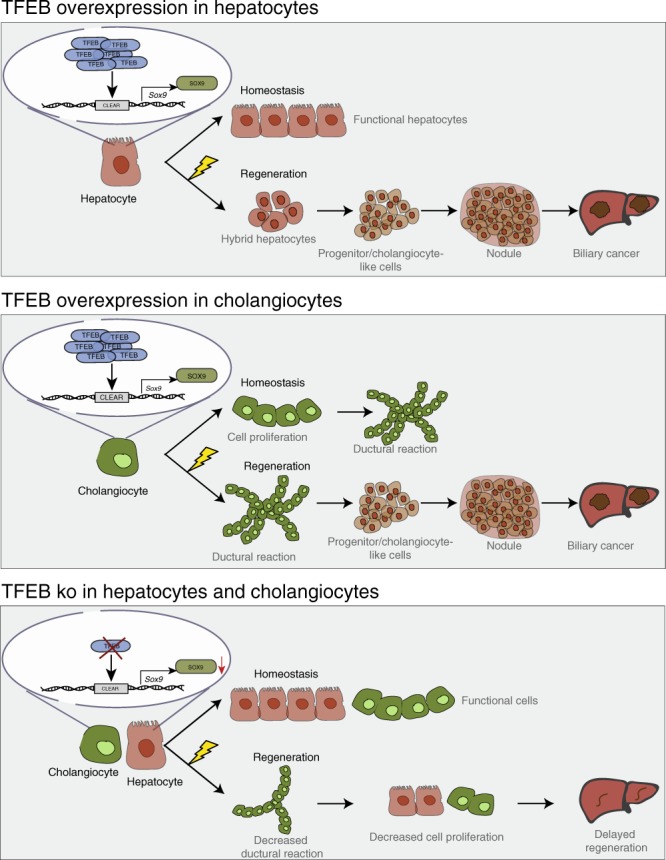

Consistent with a role of TFEB in the determination of liver cell fate, we found that mice overexpressing TFEB in the liver showed increased proliferation of progenitor cells, expansion of immature BECs and inhibition of the hepatocyte lineage. An opposite phenotype was observed in Tcfeb-depleted HBs and liver, which appeared more prone to differentiation into the hepatocyte lineage (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Schematic representation of the effects of TFEB on liver cell differentiation in vivo.

TFEB overexpression in hepatocytes does not affect hepatocyte proliferation and identity in homeostasis conditions, while it induces differentiation of hepatocytes into ductular reaction (DR)-associated cholangiocytes after injury. Conversely, TFEB overexpression in cholangiocytes induces their proliferation and DR in homeostasis and upon liver injury. On the other hand, TFEB depletion in the liver impairs normal cell regeneration after injury due to reduced induction of Sox9 expression and decreased cell proliferation.

Although liver parenchymal cells turn over slowly, the liver displays high regenerative capacity, capable of restoring 70% tissue loss within a few weeks56. This ability is vital for the liver to maintain constant mass. The population of liver cell responding to injury may differ depending on the site, type, and the duration of injury. HybHPs are located in the periportal area and express progenitor markers, such as Sox9, and hepatocyte markers, such as Hnf4α. This population of specialized hepatocytes are able to reconstitute the liver mass after various chronic injuries18. Sox9+/Hnf4α+ bi-phenotypic hepatocytes able to differentiate in either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes have been also identified in DDC-injured livers43. These cells represent the intermediate status of lineage conversion during liver regeneration. We found that conditional deletion of TFEB in the liver results in impaired LPCs activation. Moreover, we demonstrated that TFEB depleted hepatocytes fail to express Sox9 after liver damage, thus suggesting that TFEB-dependent Sox9 induction plays an important role in liver homeostasis in response to injury. This observation is in line with the known role of TFEB in the cellular adaptation to environmental cues such as various types of stress conditions30,49.

It is known that overexpression of endogenous MiT-TFE transcription factors, as a result of chromosomal abnormalities such as translocations or gene amplifications, can drive tumorigenesis in renal cell carcinoma and melanoma31,32,34,57 and to support cancer growth in pancreatic cancer32–34. However, a specific role for TFEB in cell differentiation, proliferation and neoplastic transformation in the liver has never been demonstrated. Here, we show that Albumin-CRE-driven TFEB overexpression in the liver of transgenic mice results in a severe phenotype characterized by a progressive increase in liver mass, hyperplasia of bile ducts, altered biliary tree structure, multifocal biliary cystic hyperplasia, and fibrosis. Cholestasis, bile duct proliferation, and cystic alterations rapidly progress ultimately leading to biliary tumor with features resembling CCA. Previous studies showed that SOX9 is highly upregulated in many premalignant lesions and in tumor tissues and plays a role in tumor development58–60. Our results suggest that TFEB-mediated upregulation of Sox9 expression plays a role in liver cancer development by inducing progenitor cell proliferation.

In conclusion, our study identifies an important role for TFEB in liver development and cell fate under physiological and pathological conditions. Further studies of this mechanism may lead to the identification of therapeutic targets for the modulation of liver regeneration after injury.

Methods

Mouse experiments

Experiments performed in this study were conducted in accordance with the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) with an approved protocol for the care and maintenance of laboratory animals. Mice analyzed for the study were males to reduce variability and were maintained on a C57BL/6 strain background. Housing conditions were as follows: temperature set point is 72 °F (22.2 °C), light cycle of 14 h and dark cycle of 10 h. Standard food and water were given ad libitum.

TcfebLacZ/LacZ, Tcfebflox/flox, and Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs transgenic mouse line generation has been previously described25,26. Wild type, Sox9flox/flox, R26RLSLtdTomato, Albumin-Cre, and Krt19CreERT mouse lines were obtained from the Jackson laboratory (Bar, Harbor, ME).

The Krt19CreERT was induced by three individual intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen at a dose of 4 mg. Krt19CreERT mice received 2 weeks of normal diet after the last tamoxifen injection before starting an injury diet regime.

To induce liver injury, mice were given 0.1% DDC food (Custom Animal Diet, Bangor, PA) as indicated in the text. After injury, mice were given normal chow and drinking water.

Cell culture

HBs were prepared from control and Tcfeb-3xFlagfs/fs mice at embryonic day 13.5 and immortalized by plating at clonal density61. HBs were maintained in HB media (RPMI) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE) containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin, 50 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 30 ng/ml insulin-like growth factor II (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ), 10 μg/ml insulin (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) on plates coated with rat tail collagen (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were infected with HDAd-BOS-CRE or HDAd-CMV-LacZ vectors (previously described62,63) and then cultured for the specific assay. For hepatocyte differentiation, HBs were cultured on uncoated tissue culture dishes in HB medium for up to 5 days. For bile duct differentiation, 6 cm tissue culture dishes were coated with 0.5 ml Basement Membrane Matrix (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and allowed to set for 1 h. HBs in HB cell media supplemented with 100 ng/ml recombinant mouse hepatocyte growth factor (R&D System, Minneapolis, MN) were then added to the plate. Tubule formation was monitored at 24 h, 3 days, and 10 days.

For primary mouse hepatocytes isolation, we used a two-step perfusion technique previously described64. Briefly, WT or transgenic mouse liver was perfused with collagenase (C5138; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) and digested to extract parenchymal cells out from the liver. The hepatocyte suspension was further purified using a 40% of Percoll gradient (P4937; Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), washed with Hepatocyte Wash Medium (17004-024; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and seeded at an appropriate cell density. Cells were harvested for analysis after 24 h.

Generation of TcfebKO HBs through CRISPR-Cas9

To generate TFEBKO HBs, we designed and synthetized two sgRNAs targeting adjacent regions of Tcfeb exon 3 as previously described65,66 with minimal modification. CRISPRscan67 was used to design forward primers containing the T7 promoter sequence, the proto-spacer sequence, and the sgRNA scaffold overlap sequence. Full-length sgRNA scaffold was obtained through an overlap PCR with the universal scaffold reverse primer.

Tfeb sgRNA 1 Forward:

taatacgactcactataGGGTATCTGTCTGAGACCTAgttttagagctagaaatagc

Tfeb sgRNA 2 Forward:

taatacgactcactataGGCAGGCTTCGGGGAACCTTgttttagagctagaaatagc

Universal scaffold Reverse:

gttttagagctagaaatagcaagttaaaataaggctagtccgttatcaacttgaaaaagtggcaccgagtcggtgct

In vitro transcription (IVT) was performed using the HiScribe T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis kit (NEB) following the manufacturer's instructions. A pre-complex of purified sgRNAs and spCas9 protein (IDT) was generated and then sgRNA-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNP) containing the two sgRNAs were simultaneously transfected into primary mouse HBs using the NEON Transfection System (Thermo Fisher). The electroporation conditions were: Buffer R, 1400 V, 10 ms, three pulses. Deletion efficiency was assessed through PCR using the following primers:

Tcfeb Forward: GTCCACTTCCAGTCGCCC;

Tcfeb Reverse: AGGCTAGAGGCCCATAAAGAA.

Flow cytometry and cell cycle analysis

HBs were cultured on collagen-coated plates, harvested with trypsin-EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE), and washed in PBS. For cell cycle analysis, cells were fixed in 1 ml cold 70% ethanol for 30 min on ice and then centrifuged for 5 min at high speed. The pellet was washed twice in PBS and treated with RNAseA (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Propidium iodide (PI) solution was added to the cells and the mixture incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Cell debris and dead cells were excluded from FSC-A/SSC-A dot-plots (Supplementary Fig. 10a). DNA content and relative cell cycle phases were determined based on PI relative fluorescence levels on singlets (Supplementary Fig. 10b). FACS experiments were performed using an LSRII cytometer (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA Bioscience, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed using FACSDiva (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA) and Flow-Jo (Flow-Jo, LLC, Ashland, OR) software. Cell cycle phases were quantified using the Flow-Jo Cell Cycle platform (univariate). In all experiments at least 10,000 events were acquired.

RNA extraction and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from livers using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) followed by the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA from cellular lysate was extracted using RNeasy kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using a first-strand complementary deoxyribonucleic acid kit with random primers (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The generated cDNA was diluted and used as a template for RT-PCR reactions, which was performed using the CFX96 Real Time System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Melting curve analysis were performed to verify amplification specificity. The PCR reaction was performed using iTaq SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with the following thermocycler conditions: pre-heating, 5 min at 95 °C; cycling, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 15 s at 60 °C, and 25 s at 72 °C. Relative quantification of gene expression was performed according to the 2 (−∆∆CT) method. The ß2-microglobulin, Ribosomal protein S16 or Cyclophilin genes were used as endogenous controls (reference markers). Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Western blotting

Liver and cell samples were homogenized in ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.1% SDS) supplemented with complete protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Samples were kept for 20 min at 4 °C and centrifuged at 16,000g for 10 min. Protein concentration was measured by BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Denaurated samples were resolved on a 4–20% SDS-PAGE polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and then exposed to primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies and dilution used for immuno-blots are listed in Supplementary Table 7. Uncropped blots are present in Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12.

Cellular fractionation

Enriched nuclear and cytosolic cellular subfractions were isolated by differential centrifugation, as previously described47. Liver was homogenized using a Teflon pestle and suspended in cytosol isolation buffer (250 mM sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). The lysate was then centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at 4 °C to pellet the nuclei while the supernatant (cytosol) was re-centrifuged twice at 16,000g for 20 min at 4 °C and the pellets were discarded. Nuclei were re-suspended in nuclear lysis buffer (1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 20 mM HEPES, 0.5 M NaCl, 20% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100), incubated on ice for 30 min, and then sonicated 3 Å ~10 s followed by a final centrifugation step of 15 min at 16,000g. The enriched nuclear and cytosolic fractions were analyzed by Western blot analysis.

In situ hybridization

Livers from P9 and 3-month-old WT and Tg mice were collected and frozen without prior fixation in OCT cryoprotection media. Tissue was cut into 25-μm sections, mounted on slides with ProlongGold with DAPI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and used for RNA in situ hybridization. We utilized the previously described method68 but modified the development of the signal by using a Cy3-labeled tyramide instead of the biotin-labeled tyramide. Tcfeb-probe-F1 5′-GCGGCAGAAGAAAGACAATC-3′ and Tcfeb-probe-R1 5′-AGGTGATGGAACGGAGACTG-3′ were used to amplify 1300 bp from mouse liver cDNA and cloned into pGEM_T Easy vector (Promega, Madison, MI). This template was used to generate a DIG-labeled mRNA probe using IVT reagents from Roche (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Liver staining

Dissected livers were processed for paraffin embedding as previously described47. Paraffin blocks were cut into 6 μm sections. For Sirius red staining the sections were rehydrated and stained for 1 h in picro-sirius red solution (0.1% Sirius red in a saturated aqueous solution of picric acid) (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). After two changes of acidified water (5 ml glacial acetic acid in 1 l of water), the sections were dehydrated in three washes of 100% ethanol, cleared in xylene, and mounted on a resinous medium. X-Gal and H&E stainings were performed following the IHC World protocol. For immunostaining, the sections were rehydrated to PBS pH 7.4 and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton in PBS. Heat Induced Epitope Retrieval using the citrate buffer method (pH 6.0) was performed to retrieve the antigen sites. The sections were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with blocking solution (3% BSA, 5% donkey serum, 20 mM MgCl2, 0.3% Tween 20 in PBS pH 7.4). For co-stainings, primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies made in donkey were: AlexaFluor-488 anti-rabbit and AlexaFluor-555 anti-mouse (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Slides were mounted on ProlongGold with DAPI (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For IHC, the Vectastain ABC kit and DAB (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) were used following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sections were counterstained using Mayer’s hematoxylin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). For BrdU staining, 2 mg of BrdU (BD Bioscience) diluted in PBS 1× was injected by intraperitoneal injection 4 h before tissue collection. Livers were dissected, fixed, with buffered 10% formalin overnight at 4 °C and embedded into OCT blocks and cut into 10-μm sections. BrdU signal was revealed by using a rat anti-BrdU antibody. Stained liver sections were examined under a Zeiss Axiocam MR microscope and analyzed using Zen black software. For staining quantification, Image J Software (NIH) was used to calculate the percent area positively stained in five random low power views.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA from HBs 3 days after hepatocytic differentiation was quantified using the Qubit 2.0 fluorimetric Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Libraries were prepared from 100 ng of total RNA using the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit FWD for Illumina (Lexogen GmbH). Quality of libraries was assessed by using screen tape High sensitivity DNA D1000 (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system using an S1, 100 cycles flow cell (Illumina Inc.). Sequence reads were trimmed using bbduk software (bbmap suite 37.31) to remove adapter sequences, poly-A tails, and low-quality end bases (regions with average quality below 6). Alignment was performed with STAR 2.6.0a on mm10 reference assembly. The expression levels of genes were determined with htseq-count 0.9.1 by using mm10 Ensembl assembly (release 90). We have filtered out all genes having <1 cpm in less than two samples. Differential expression analysis was performed using edgeR69.

Microarray analysis was performed on liver from P9 mice of each of the two genotypes (n = 3 per group). All samples were processed on Affymetrix Mouse 430A 2.0 arrays using GeneChip 3′-IVT Plus and Hybridization Wash and Stain kits by means of Affymetrix standard protocols. Raw intensity values of the six arrays were processed and normalized by Robust Multi-Array Average Method70 using the Bioconductor R package Affy71. The data have been deposited in NCBIs Gene Expression Omnibus72 (GEO) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE35015.

Enrichment analyses of KEGG pathways on differentially expressed genes were performed using the Bioconductor R package clusterProfiler (FDR ≤ 0.05). Gene GSEA was run on HNF4α targets downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB)73.

Promoter analysis

The analysis of TFEB binding sites was performed using the CLEAR matrix74 and the matchPWM algorithm implemented in the Biostrings package. Putative binding sites were filtered with threshold of significance set at 0.8.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed using livers of 2-month-old Alb-Cre;Tcfeb-3xFlag and control mice as previously described30. Primers used for RT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 8.

Luciferase assay

The Sox9 promoter was amplified from mouse genomic DNA and cloned into the pGL4 plasmid (Promega, Madison, MI). A quick-change site directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) was used for the mutagenesis of CLEAR sites in the Sox9 promoter. Primers used for mutagenesis are listed in Supplementary Table 9. The Sox9 promoter-reporter luciferase construct was transfected along with the pRL-TK (Promega, Madison, MI) in control HBs and HBs overexpressing Tcfeb. Twenty-four hours after transfection cells were collected and subjected to luminescence detection by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega, Madison, MI). The luminescence was measured using a Turner Designs Luminometer (DLReady) (Promega, Madison, MI) and normalized against Renilla luciferase activity.

Biliary tree casting

Two-month-old mice were euthanized with isoflurane (Vedco Saint Joseph MO). Ink (Hyatt’s) was injected into the common bile duct using a 30-gauge needle. The entire liver was removed, formalin-fixed, and clarified in a 1:2 solution of benzyl alcohol and benzyl benzoate.

Blood chemistry analysis

Blood samples were collected by retroorbital bleeding. Serum was frozen at −80 °C or used immediately after collection. Total Bile Acids (TBA) Enzymatic Cycling Assay Kit was obtained from BQKITS (San Diego, CA).

Vector production and injections

pAAV-TBG-GFP-pA (GFP) was obtained from Thomas Vallim (University of California, Los Angeles). pAAV-TBG-PI-Cre-rBG (Cre Recombinase) and plasmids required for AAV packaging, adenoviral helper plasmid pAdDeltaF6 (PL-F-PVADF6), and AAV8 packaging plasmid pAAV2/8 (PL-T-PV0007) were obtained from the University of Pennsylvania Vector Core. AAV were generated as previously described with some modifications75,76. Each AAV transgene construct was co-transfected with the packaging constructs into 293 T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216) using polyethylenimine (PEI). Cell pellets were harvested and purified using a single cesium chloride density gradient centrifugation. Fractions containing AAV vector genomes were pooled and then dialyzed against PBS using a 100kD Spectra-Por® Float-A-Lyzer® G2 dialysis device (Spectrum Labs, G235059) to remove the cesium chloride. Purified AAV were concentrated using a Sartorius™ Vivaspin™ Turbo 4 Ultrafiltration Unit (VS04T42) and stored at −80 °C until use. AAV titers were calculated after DNase digestion using the qPCR standard method. Primers used for titer are included in Supplementary Table 10. Viruses were administered by retroorbital injection at the dose of 2 × 1011 genome copies/mouse.

Statistical analyses

Data are expressed as averages ± standard error. Statistical significance was computed using GraphPad Prism v7 using Student’s two-tailed t-test or two-way ANOVA as indicated in the figure legends. A p value <0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Huda Zoghbi, Nicola Brunetti-Pierri, Roberto Zoncu, Rushika Perera, and Graciana Diez Roux for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to Diego Carrella and Rossella De Cegli (TIGEM) for promoter analysis and ChIP primer design. We thank Dr. Thomas Vallim (University of California, Los Angeles) for the pAAV-TBG-GFP plasmid. We also thank the NGS Core at TIGEM for help with gene expression analysis. This work was supported by a grant from the US National Institutes of Health (R01-NS078072), AIRC (Italian Association for Cancer Research) (IG 2015-17639), Foundation Louis-Jeantet and Telethon Foundation to A.B. The project was supported in part by the RNA In Situ Hybridization Core facility at Baylor College of Medicine which is supported by a Shared Instrumentation grant from the NIH (1S10OD016167) and the NIH IDDRC Grant (1U54HD083092-02) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. This project was also supported in part by the NIDDK Digestive Disease Center Core with funding from the NIH (NIH P30DK58338) and in part by the Pathology and histology Core at Baylor College of Medicine with funding from the NIH (NCI-CA125123).

Source data

Author contributions

N.P. performed the experiments, interpreted the results, and generated the Fig.9. T.H., N.J.H., A.C., and L.D. provided technical support to N.P. T.J.K. performed ChIP experiments. L.B. helped with the generation of CRISPR/Cas9 clones and with FACS analysis. K.K. isolated primary hepatocytes. M.D.G., A.H., and W.R.L. provided AAV8 viruses. A.C. and M.M. analyzed the gene expression data. N.A., D.D.M., C.S., M.J.F., and S.J.F. contributed to interpretation of the results. A.B. and N.P designed the overall study, supervised the work, and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBIs Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the accession code GSE35015.

The source data underlying Figs. 2b, c, f, 3c, 4a–d, 5b–d, f, 6b, 7b, 8c, e, Supplementary Figs. 1c, d, 2e, 3c, 4a, 8a–d, 9a, d are provided as a Source Data file.

Competing interests

A.B. is a co-founder of CASMA Therapeutics, Boston, MA, USA. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Masaaki Komatsu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nunzia Pastore, Email: pastore@tigem.it.

Andrea Ballabio, Email: ballabio@tigem.it.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-16300-x.

References

- 1.Zhao R, Duncan SA. Embryonic development of the liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:956–967. doi: 10.1002/hep.20691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boulter L, Lu WY, Forbes SJ. Differentiation of progenitors in the liver: a matter of local choice. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:1867–1873. doi: 10.1172/JCI66026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sell S. Heterogeneity and plasticity of hepatocyte lineage cells. Hepatology. 2001;33:738–750. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tarlow BD, et al. Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yanger K, et al. Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes Dev. 2013;27:719–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.207803.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Hepatocytes, rather than cholangiocytes, can be the major source of primitive ductules in the chronically injured mouse liver. Am. J. Pathol. 2014;184:1468–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yanger K, et al. Adult hepatocytes are generated by self-duplication rather than stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaub JR, et al. De novo formation of the biliary system by TGFbeta-mediated hepatocyte transdifferentiation. Nature. 2018;557:247–251. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0075-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng, X. et al. Chronic liver injury induces conversion of biliary epithelial cells into hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.022 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Raven A, et al. Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature. 2017;547:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature23015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yovchev MI, et al. Identification of adult hepatic progenitor cells capable of repopulating injured rat liver. Hepatology. 2008;47:636–647. doi: 10.1002/hep.22047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roskams TA, Libbrecht L, Desmet VJ. Progenitor cells in diseased human liver. Semin. Liver Dis. 2003;23:385–396. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-815564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lowes KN, Croager EJ, Abraham LJ, Olynyk JK, Yeoh GC. Upregulation of lymphotoxin beta expression in liver progenitor (oval) cells in chronic hepatitis C. Gut. 2003;52:1327–1332. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, et al. Osteopontin induces ductular reaction contributing to liver fibrosis. Gut. 2014;63:1805–1818. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khuu DN, Nyabi O, Maerckx C, Sokal E, Najimi M. Adult human liver mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells participate in mouse liver regeneration after hepatectomy. Cell Transplant. 2013;22:1369–1380. doi: 10.3727/096368912X659853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, et al. Human hepatocyte growth factor (hHGF)-modified hepatic oval cells improve liver transplant survival. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kopp JL, Grompe M, Sander M. Stem cells versus plasticity in liver and pancreas regeneration. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:238–245. doi: 10.1038/ncb3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Font-Burgada J, et al. Hybrid periportal hepatocytes regenerate the injured liver without giving rise to cancer. Cell. 2015;162:766–779. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilgenkrantz H, Collin de l’Hortet A. Understanding liver regeneration: from mechanisms to regenerative medicine. Am. J. Pathol. 2018;188:1316–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roskams T. Liver stem cells and their implication in hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2006;25:3818–3822. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita T, Wang XW. Cancer stem cells in the development of liver cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:1911–1918. doi: 10.1172/JCI66024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemesath TJ, et al. microphthalmia, a critical factor in melanocyte development, defines a discrete transcription factor family. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2770–2780. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.22.2770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steingrimsson E, Tessarollo L, Reid SW, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG. The bHLH-Zip transcription factor Tfeb is essential for placental vascularization. Development. 1998;125:4607–4616. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sardiello M, et al. A gene network regulating lysosomal biogenesis and function. Science. 2009;325:473–477. doi: 10.1126/science.1174447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Settembre C, et al. TFEB links autophagy to lysosomal biogenesis. Science. 2011;332:1429–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1204592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Settembre C, et al. A lysosome-to-nucleus signalling mechanism senses and regulates the lysosome via mTOR and TFEB. EMBO J. 2012;31:1095–1108. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roczniak-Ferguson A, et al. The transcription factor TFEB links mTORC1 signaling to transcriptional control of lysosome homeostasis. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:ra42. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martina JA, Chen Y, Gucek M, Puertollano R. MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy. 2012;8:903–914. doi: 10.4161/auto.19653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansueto G, et al. Transcription factor EB controls metabolic flexibility during exercise. Cell Metab. 2017;25:182–196. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Settembre C, et al. TFEB controls cellular lipid metabolism through a starvation-induced autoregulatory loop. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013;15:647–658. doi: 10.1038/ncb2718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haq R, Fisher DE. Biology and clinical relevance of the micropthalmia family of transcription factors in human cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:3474–3482. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.6223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calcagni, A. et al. Modelling TFE renal cell carcinoma in mice reveals a critical role of WNT signaling. eLife5, e17047 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Perera, R. M. et al. Transcriptional control of autophagy-lysosome function drives pancreatic cancer metabolism. Nature 524, 361–365 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Di Malta C, et al. Transcriptional activation of RagD GTPase controls mTORC1 and promotes cancer growth. Science. 2017;356:1188–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.aag2553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoneshima E, et al. The transcription factor EB (TFEB) regulates osteoblast differentiation through ATF4/CHOP-dependent pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2016;231:1321–1333. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orfali, N. et al. All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) induced TFEB expression is required for myeloid differentiation in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL). Eur. J. Haematol. 10.1111/ejh.13367 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Betschinger J, et al. Exit from pluripotency is gated by intracellular redistribution of the bHLH transcription factor Tfe3. Cell. 2013;153:335–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Villegas F, et al. Lysosomal signaling licenses embryonic stem cell differentiation via inactivation of Tfe3. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:257–270. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zorn, A. M. Liver Development (StemBook, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008).

- 40.Lemaigre FP. Development of the biliary tract. Mechanisms Dev. 2003;120:81–87. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisend CM, Kundert JA, Suvorova ES, Prigge JR, Schmidt EE. Cre activity in fetal albCre mouse hepatocytes: utility for developmental studies. Genesis. 2009;47:789–792. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Neill KE, et al. Hepatocyte-ductal transdifferentiation is mediated by reciprocal repression of SOX9 and C/EBPalpha. Cell Reprogram. 2014;16:314–323. doi: 10.1089/cell.2014.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanimizu N, Nishikawa Y, Ichinohe N, Akiyama H, Mitaka T. Sry HMG box protein 9-positive (Sox9+) epithelial cell adhesion molecule-negative (EpCAM-) biphenotypic cells derived from hepatocytes are involved in mouse liver regeneration. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:7589–7598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.517243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yimlamai D, et al. Hippo pathway activity influences liver cell fate. Cell. 2014;157:1324–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martina JA, et al. The nutrient-responsive transcription factor TFE3 promotes autophagy, lysosomal biogenesis, and clearance of cellular debris. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra9. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF: master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol. Med. 2006;12:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pastore N, et al. TFE3 regulates whole-body energy metabolism in cooperation with TFEB. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017;9:605–621. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201607204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Najibi M, Labed SA, Visvikis O, Irazoqui JE. An evolutionarily conserved PLC-PKD-TFEB pathway for host defense. Cell Rep. 2016;15:1728–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastore N, et al. TFEB and TFE3 cooperate in the regulation of the innate immune response in activated macrophages. Autophagy. 2016;12:1240–1258. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1179405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Visvikis O, et al. Innate host defense requires TFEB-mediated transcription of cytoprotective and antimicrobial genes. Immunity. 2014;40:896–909. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pastore, N. et al. Nutrient-sensitive transcription factors TFEB and TFE3 couple autophagy and metabolism to the peripheral clock. EMBO J. 10.15252/embj.2018101347 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Steingrimsson E, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Melanocytes and the microphthalmia transcription factor network. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:365–411. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leeman DS, et al. Lysosome activation clears aggregates and enhances quiescent neural stem cell activation during aging. Science. 2018;359:1277–1283. doi: 10.1126/science.aag3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kyrmizi I, et al. Plasticity and expanding complexity of the hepatic transcription factor network during liver development. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2293–2305. doi: 10.1101/gad.390906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Antoniou A, et al. Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2325–2333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michalopoulos GK. Principles of liver regeneration and growth homeostasis. Compr. Physiol. 2013;3:485–513. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c120014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kauffman EC, et al. Molecular genetics and cellular features of TFE3 and TFEB fusion kidney cancers. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2014;11:465–475. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomsen MK, et al. SOX9 elevation in the prostate promotes proliferation and cooperates with PTEN loss to drive tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:979–987. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ling S, et al. An EGFR-ERK-SOX9 signaling cascade links urothelial development and regeneration to cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3812–3821. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Matheu A, et al. Oncogenicity of the developmental transcription factor Sox9. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1301–1315. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strick-Marchand H, Weiss MC. Inducible differentiation and morphogenesis of bipotential liver cell lines from wild-type mouse embryos. Hepatology. 2002;36:794–804. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palmer D, Ng P. Improved system for helper-dependent adenoviral vector production. Mol. Ther. 2003;8:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Terashima T, et al. DRG-targeted helper-dependent adenoviruses mediate selective gene delivery for therapeutic rescue of sensory neuronopathies in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119:2100–2112. doi: 10.1172/JCI39038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seglen PO. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 1976;13:29–83. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)61797-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gundry MC, et al. Highly efficient genome editing of murine and human hematopoietic progenitor cells by CRISPR/Cas9. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1453–1461. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brunetti, L., Gundry, M. C., Kitano, A., Nakada, D. & Goodell, M. A. Highly efficient gene disruption of murine and human hematopoietic progenitor cells by CRISPR/Cas9. J. Vis. Exp.134, 10.3791/57278 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Moreno-Mateos MA, et al. CRISPRscan: designing highly efficient sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 targeting in vivo. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:982–988. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yaylaoglu MB, et al. Comprehensive expression atlas of fibroblast growth factors and their receptors generated by a novel robotic in situ hybridization platform. Dev. Dyn. 2005;234:371–386. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gautier L, Cope L, Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA. affy–analysis of Affymetrix GeneChip data at the probe level. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:307–315. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palmieri M, et al. Characterization of the CLEAR network reveals an integrated control of cellular clearance pathways. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:3852–3866. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jarrett KE, et al. Somatic editing of Ldlr with adeno-associated viral-CRISPR is an efficient tool for atherosclerosis tesearch. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018;38:1997–2006. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lagor WR, Johnston JC, Lock M, Vandenberghe LH, Rader DJ. Adeno-associated viruses as liver-directed gene delivery vehicles: focus on lipoprotein metabolism. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;1027:273–307. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-369-5_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBIs Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under the accession code GSE35015.