Abstract

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have reported substantial single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with major depressive disorder (MDD), but the underlying functional variations in the GWAS risk loci are unclear. Here we show that the European MDD genome-wide risk-associated allele of rs12129573 at 1p31.1 is associated with MDD in Han Chinese, and this SNP is in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with a human-unique Alu insertion polymorphism (rs70959274) in the 5′ flanking region of a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) LINC01360 (Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNA 1360), which is preferably expressed in human testis in the currently available expression datasets. The risk allele at rs12129573 is almost completely linked with the absence of this Alu insertion. The Alu insertion polymorphism (rs70959274) is significantly associated with a lower RNA level of LINC01360 and acts as a transcription silencer likely through modulating the methylation of its internal CpG sites. Luciferase assays confirm that the presence of Alu insertion at rs70959274 suppresses transcriptional activities in human cells, and deletion of the Alu insertion through CRISPR/Cas9-directed genome editing increases RNA expression of LINC01360. Deletion of the Alu insertion in human cells also leads to dysregulation of gene expression, biological processes and pathways relevant to MDD, such as the alterations of mRNA levels of DRD2 and FLOT1, transcription of genes involved in synaptic transmission, neurogenesis, learning or memory, and the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. In summary, we identify a human-unique DNA repetitive polymorphism in robust LD with the MDD risk-associated SNP at the prominent 1p31.1 GWAS loci, and offer insights into the molecular basis of the illness.

Subject terms: Functional genomics, Epigenetics, Gene regulation, Depression

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a severe mental illness substantially influenced by genetic and environmental risk factors [1]. Recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple common single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) conferring risk of MDD [2–4], such as variations spanning VRK2, DRD2, TCF4, and the extended major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region [4–6]. Majority of the risk SNPs for MDD are located in noncoding genomic regions, and identifying the functional variations among the noncoding SNPs is crucial for translating the clinical associations into molecular mechanisms and for understanding the biological basis of the illness [7, 8]. Likewise, there are many studies aiming to characterize the functional causative SNPs in the psychiatric GWAS risk loci [9–13]. However, both GWAS analyses and follow-up functional studies primarily focus on SNPs and small indels, and other types of sequence variations are relatively less investigated. Nevertheless, accumulating data have shown that sequence variations besides SNPs, such as variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs), Alu short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs), copy number variations (CNVs), and short tandem repeats (STRs), may also confer significant risk of psychiatric disorders, and some of them might be the functional units to which GWAS SNP associations are attributed [14–19].

Among these sequence variations, Alu polymorphisms are potentially important players in complex illnesses whose impact remains less characterized. Alu polymorphisms refer to the presence or absence of an Alu insertion (mobile genetic elements that are ~300-bp stretch of repetitive DNA sequences ancestrally derived from the small cytoplasmic 7SL RNA) [20]. Most Alu insertions are fixed in populations, while some are still polymorphic (comprised of presence (insertion) and absence (empty) alleles) [21]. Intriguingly, Payer et al. have previously identified many Alu polymorphisms in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) with GWAS risk SNPs of complex diseases [14]. Therefore, a comprehensive post-GWAS analysis of risk loci considering all types of sequence variations is important to identify potential causative variations and will aid in the understanding of genetic mechanisms for psychiatric disorders.

There is a GWAS risk locus at 1p31.1 in which rs12129573 and its index SNPs are genome-wide significantly associated with MDD in Europeans (p = 4.01 × 10−12 in 135,458 cases and 344,901 controls) [4]. Here we replicate the association between rs12129573 and clinical diagnosis of MDD across distinct populations. Moving beyond statistical analysis, we have discovered a human-unique Alu polymorphism (rs70959274), which is in strong LD with rs12129573, in the promoter of LINC01360 (Long Intergenic Non-Protein Coding RNA 1360). Through both in vitro luciferase reporter gene assays and CRISPR/Cas9 editing-generated HEK293T and U251 cells with different Alu polymorphisms, we reveal that absence of the Alu insertion predicts a higher transcription level of LINC01360 in cells; eQTL analyses also suggest that the absence of the Alu insertion correlates to higher expression of LINC01360 in the human tissue. We then show that the Alu insertion likely serves as a transcription silencer of LINC01360 through modulating DNA methylation. Our results describe a novel human-specific Alu insertion as a potential causative variation explaining the GWAS risk associations in the 1p31.1 locus.

Methods

MDD case-control sample and statistical analysis in Chinese population

1751 MDD cases and 2468 controls of Han Chinese origin were recruited for the current study. MDD patients were diagnosed according to the DSM-IV criteria via standard diagnostic assessments, supplemented with clinical information through thorough review of medical records and interview with family informants [22, 23]. Those who were diagnosed with other psychiatric disorders or neurological disorders, being pregnant, or breast-feeding at the time of study were excluded. Control subjects were local volunteers with no history of self-reported mental illnesses. All the protocols and methods used in this study were approved by the institutional review board of the Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences and the ethics committees of all participating hospitals and universities. All participants provided informed consents. Genomic DNA was extracted using high-salt method [24]. The PCR primers amplifying the DNA fragments spanning rs12129573 (PCR product length: 458-bp) were 5′-TGTCCTCAGCAAGAGAATGTGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AATGTTAATCTGGATGCTTTCGG-3′ (reverse), and SNP genotyping was conducted using the SNaPShot method as previously described [25]. We also confirmed the genotyping of rs12129573 of 50 randomly selected individuals using Sanger sequencing, and no genotyping errors were found. We applied logistic regression to analyze the associations between SNPs and MDD using PLINK v1.9 [26], with sex and residence of participants included in the covariates. Regional association results of the 1p31.1 loci were plotted using LocusZoom (http://locuszoom.sph.umich.edu/locuszoom/) [27].

Sequence variation analysis and genotyping of the Alu polymorphism in human populations

We examined the UCSC website (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) to identify all types of potential sequence variations in the 1p31.1 region. Genotyping of the Alu polymorphism (rs70959274) was conducted using PCR in 191 samples (including 135 Han Chinese, 36 European and 20 Pakistani individuals), and amplicons were analyzed with electrophoresis and Sanger sequencing to determine different alleles. The PCR primers for genotyping of rs70959274 were 5′-GCACAATGCAAATATGCCTTAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCATCCTCCATACACAAAACAT-3′ (reverse) (PCR product length: presence of Alu insertion: 495-bp; absence of Alu insertion: 144-bp).

Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis in human tissues

To identify the impact of risk SNP rs12129573 on mRNA expression, we utilized GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression project; https://www.gtexportal.org/) dataset to explore the gene expression regulation in human tissues [28]. Genes within 150-Kb away from the risk SNP rs12129573 were analyzed for its eQTL effects. As described in the original GTEx report [28], linear regression was conducted between genes and normalized expression matrices, with top three genotyping principal components, gender, genotyping platforms included as covariates. Detailed information of the GTEx dataset can be found in the original study and on their official website [28].

Defining candidate regulatory variations

The pairwise LD (r2) between sequence variations were calculated using the Haploview program [29]. We used the SNP data from the 1000 Genomes Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/) to identify variations in strong LD (r2 ≥ 0.8) with the MDD risk SNP rs12129573 in Europeans [30]. We used HaploReg v4.1 (https://pubs.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php) dataset to help prioritize the candidate regulatory SNPs [31], which primarily utilized ChIP-Seq results of histone modifications such as H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9ac and H3K27ac in brain tissues and multiple types of cells from the ENCODE dataset [32]. We then utilized GWAVA (Genome Wide Annotation of VAriants, https://www.sanger.ac.uk/sanger/StatGen_Gwava, a web-based tool aiming to prioritize the functional variations based on the annotations of noncoding elements primarily from ENCODE/GENCODE, as well as the genome-wide properties such as evolutionary conservation and GC-content), to predict whether the epigenetic features and regulatory elements overlapped with the tested SNPs [33]. We also used AliBaba 2.1 program (http://gene-regulation.com/pub/programs/alibaba2/index.html), which is developed based on the binding sites resources from TRANSFAC® Public [34], to predict the potential binding sites of transcription factors within the Alu sequence at rs70959274.

Cell culture

The HEK293T (human embryonic kidneys 293T) and U251 (human glioma) cell lines were originally obtained from the Kunming Cell Bank, Kunming Institute of Zoology, and HCC1806 (human mammary gland epithelial) cell line was originally obtained from ATCC. PCR and microscope analyses are regularly performed to ensure that no cells were contaminated with mycoplasma during the study. All cells were cultured in a standard humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HEK293T and U251 cells were cultured in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) basic (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biological Industries), 1% non-essential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Life Technologies). HCC1806 cells were cultured in RPMI Medium 1640 Basic (Gibco) supplemented with 5% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

LINC01360 promoter activities characterized by luciferase reporter assays

Plasmid construction in pGL3-promoter vector

DNA fragments containing different alleles at rs70959274 were amplified for luciferase assays using the primers 5′-AAAGACTGCAAAGGCTTCCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCATATCCATCCTCCATACAC-3′ (reverse) (PCR product length: presence of Alu insertion: 909-bp; absence of Alu insertion: 558-bp). The sequences were then sub-cloned into pGL3-promoter vector (Promega, #E1761), and Sanger sequencing was performed to ensure that the recombinant clones only differ at rs70959274.

Transfection and luciferase reporter gene assay

The reconstructed pGL3 reporters were transiently co-transfected into HEK293T, U251, and HCC1806 cells together with an internal control reporter pRL-TK (Promega, #E224A) using Lipofectamine 3000 (Life Technologies). These plasmids were all accurately quantified and equal amounts of the plasmids were used for transfection between different wells in 24-well plate. All transfection procedures lasted 24–48 h, and the cells were then collected to measure luciferase activity using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). The activity of firefly luciferase was normalized to that of Renilla luciferase to control for variations in the transfection efficiency between different wells. All assays were performed at least in four biological replicates in independent experiments, and two-tailed t-tests were performed to analyze statistical differences between experimental groups.

Prediction of CpG islands within the Alu sequence at rs70959274 and bisulfite sequencing

EMBOSS Cpgplot (http://emboss.bioinformatics.nl/cgi-bin/emboss/cpgplot) was used to identify CpG islands (CGIs) in the Alu insertion sequence [35]. The default parameters of prediction were as follows: 1) the observed CpG/expected CpG ratios > 0.6; 2) %C + %G > 50%; and 3) sequence length > 200-bp.

We used ZYMO EZ DNA Methylation-GoldTM Kit to conduct bisulfite conversions of DNA following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sodium bisulfite converts unmethylated cytosine to uracil, which is then PCR amplified as thymidine while methylated cytosine remains cytosine. The Bisulfite sequencing PCR primers were 5′-GTGAAGTTTAGATTTGAGATTTTAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TCCATACACAAAACATACATTCT-3′ (reverse), and PCR was performed at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 55 °C for 30 sec and 72 °C for 1 min with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. PCR products from bisulfite-treated DNA were tested in 2% agarose gel and then cloned into the pEASY-T1 vector (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). The colony PCR was undertaken to screen for positive colonies. The clones of PCR products with the right size were sequenced on an ABI sequencer with dye terminators (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The methylation frequencies of all CpG sites were determined for ten clones.

CRISPR/Cas9 guide selection and genome deletion of rs70959274 region

Protospacer sequences of CRISPR/cas9 against target regions were designed by CRISPOR (http://crispor.tefor.net/crispor.py) [36]. We deleted the 1278-bp DNA sequence encompassing rs70959274 using two Cas9-guide RNA constructs. Annealed oligonucleotides were sub-cloned into the pL-CRISPR.EFS.GFP plasmid, which simultaneously delivers spCas9, GFP, and sgRNA. The sgRNA sequences were 5′-AGACATAATCCCAATATCTG-3′ (upstream) and 5′-GAGTTAGAAAATTAGGACAG-3′ (downstream).

The HEK293T, U251, and HCC1806 cells were cultured on 6-well plates and allowed to grow to ~85% confluency; HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with the pL-CRISPR.EFS.GFP-sgRNA (or pL-CRISPR.EFS.GFP-control-sgRNA which did not target human genome) constructs using Lipofectamine 3000, while U251 and HCC1806 cells were infected with pL-CRISPR.EFS.GFP-sgRNA (or pL-CRISPR.EFS.GFP-control-sgRNA) lentivirus. In all, 48 h after transfection or 72 h after infection, cells with strong GFP fluorescence signals were identified with a confocal microscopy and proceeded for genomic DNA extraction. The target region was then amplified, and electrophoresis and Sanger sequencing were performed to confirm successful editing of the genome as previously described [37]. Cells with and without editing of the target region were then allowed to grow to establish sublines. Eventually, three non-deleted and three biallelic deleted sublines after CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing were selected for subsequent RNA extraction, complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), and RNA-sequencing.

Detection of off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9

Detection of off-target effects during CRISPR/Cas9 was performed following our previous study [37]. We predicted 28 most likely off-target sites in the genome using the tools provided at http://crispor.tefor.net/crispor.py. Briefly, DNA fragments differed by less than three nucleotides compared with the target sequence were considered potential off-target sites. These DNA fragments were amplified using PCR from HEK293T cells that were used for the CRISPR/cas9 mediated deletion of the Alu polymorphism at rs70959274. The T7EN1 cleavage assay was then performed to examine the cleavage of off-target sites. Specifically, a total of 200 ng purified PCR products were denatured and reannealed in 1× NEB Buffer 2 (NEB) in 20 μl volume using a thermocycler with the following program: 95 °C, 5 min; 95–85 °C at −2 °C/s; 85–25 °C at −0.1 °C/s; hold at 4 °C. In all, 1 μl of T7EN1 enzymes (NEB) were then added to hybridize PCR products and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. The PCR products digested by T7EN1 were separated on a 2% agarose gel and images were captured by Tanon 5200 Multi.

Real-time quantitative PCR analyses in cells

Total cellular RNA was isolated from HEK293T, U251 and HCC1806 cells using TRIzol reagent. The cDNA was then synthesized from the total RNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo, #K1622). An aliquot of 2 μg total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA in a 20 μl reaction mixture containing Random Hexamer Primer, RevertAid M-MuLV RT, RiboLock RNase Inhibitor, DNase I, 5× Reaction Buffer and 10 mM dNTP Mix (Thermo). The mRNA expression was quantified through RT-qPCR using the ABI PRISM 7900 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) as previously described [6, 38, 39]. RPS13 was used as the reference gene to normalize the amplification signal between different wells and the amount of input cDNA. The primers used for amplification of RPS13 were 5′-CCCCACTTGGTTGAAGTTGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTGTGCAACACCATGTGAA-3′ (reverse); primers for LRRIQ3 were 5′-CGATTTGTCTGACTGTGTTGGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CATGACTGGTTAGCTCTTCTGTGA-3′ (reverse); primers for NEGR1 were 5′-TGCAGTGCGGAAAATGATGTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTTATCAGGCCACTGCGTCC-3′ (reverse). Relative mRNA levels of these genes were presented as the means of 2−ΔΔCt. Statistical tests against different groups were conducted using two-tailed t-test.

Two pairs of primers were used to quantify the expression of LINC01360. The first pair (the forward and reverse primers were located in different exons) were 5′-CAGGCTGAGGGATGTTAGGAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGAGGTGACAGGGAGTTTGGT-3′ (reverse); the second pair (the forward and reverse primers were located in the same exon) were 5′-TTCCAAGGGCCAATTTTGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAGGCCCAGTTTGCGTCAT-3′ (reverse). The first pair of LINC01360 primers is supposed to measure the expression of only part of its transcripts; the second pair is predicted to measure the expression of majority of the LINC01360 transcripts. The predicted transcripts of LINC01360 in the Ensembl website and locations of each primer are shown in Fig. S1. Since LINC01360 is not quantifiable in some samples and cannot be statistically analyzed using RT-qPCR, we conducted semi-quantitative PCR and the amplicons were separated on 2% agarose gels to examine the accuracies and intensities of the PCR product bands. The semi-quantitative PCR of LINC01360 was performed on an Applied Biosystems Veriti Thermal Cycler following the program that firstly 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 40 repeated cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s, with one final annealing cycle at 72 °C for 5 min.

RNA-sequencing analysis in HEK293T and U251 cells

Paired-end RNA-sequencing analysis was performed for the HEK293T and U251 cells with and without CRISPR-mediated deletion of the Alu insertion. RNA-sequencing was conducted on Illumina NovaSeq 6000 with a 150-bp read length. Fastq data files were retrieved for sequencing quality and trim reads examination using trimmomatic-0.36 [40]. This process yielded results of clean paired-end reads, which were subsequently aligned to the GRCh38 of the human genome using Hisat2 [41]. FeatureCounts were used to quantify mRNA expression of genes annotated in the Ensembl build GRCh38.91 [42], and genes with average FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase Per Million Mapped Fragments) < 0.1 were excluded from further differential expression analyses. R package DESeq2 was used to analyze the gene expression differences between experimental groups [43]. Genes with false discovery rate (FDR) corrected p-value < 0.05 were identified as significantly differentially expressed.

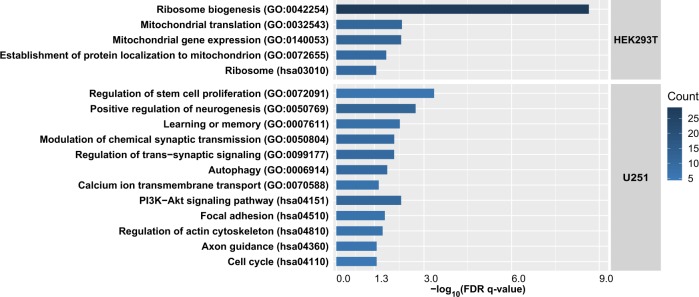

Biological processes and pathway analyses

To examine whether genes involved in essential pathways in MDD pathogenesis and relevant psychological characteristics are affected by the rs70959274 Alu polymorphism, functional annotation analyses with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway annotation and Gene Ontology (GO) annotation were performed using R package clusterProfiler [44]. KEGG pathways and GO biological process (BP) terms with a gene number <5 were excluded, and KEGG pathways and GO BP terms with FDR-corrected p-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significantly enriched. Semantic similarity analyses were then conducted with GOSemSim [45] to narrow down the enriched GO terms based on their similarity between each other (r > 0.5 was considered highly similar).

Results

rs12129573 is significantly associated with MDD in Han Chinese population

The MDD GWAS in European populations discovered significant associations of 44 independent risk loci, among which rs12129573 in 1p31.1 showed genome-wide significant associations (p = 4.01 × 10−12 in 135,458 cases and 344,901 controls) [4]. In our Han Chinese samples (1751 MDD cases and 2468 controls), the putative risk A-allele of rs12129573 was also significantly overrepresented in MDD patients compared with healthy controls (p = 2.98 × 10−5, OR = 1.239, Table S1). The allele and genotype frequencies of the SNP are shown in Table S1, and there is no deviation of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium in controls.

rs12129573 is significantly associated with a lower RNA expression of LINC01360

The rs12129573 locates in the 5′ flanking region of LINC01360 (Fig. 1). LINC01360 encodes a lncRNA with unknown function, and is also the only annotated gene within 150-Kb around the SNP. Accumulating evidence have suggested that noncoding risk variations of complex disorders tend to be associated with mRNA expression of nearby or distal genes [7], we therefore examined the associations between rs12129573 and the mRNA expression of all its potential cis-acting genes (<1-Mb) in multiple public brain eQTL datasets (BrainSeq [46], CommonMind [47], Brain xQTL [48] and GTEx-brain [28]). Unfortunately, rs12129573 was not associated with the mRNA expression of any genes in the brain tissues (data not shown).

Fig. 1. Genetic associations of SNPs spanning 1p31.1 region with major depressive disorder (MDD) in European populations, and schematic of rs12129573 and Alu polymorphism (rs70959274) locations in human genome.

A physical map of the region is given and depicts known genes within the region, and the LD is defined based on the SNP rs12129573. The dash line indicates the threshold for genome-wide significance (p = 5.00 × 10−8). Note: in the PGC2 MDD GWAS, rs12129573 showed genome-wide significant association (p = 4.01 × 10−12) with the illness in 135,458 cases and 344,901 controls. However, the summary statistics of 23andMe dataset (75,607 cases and 231,747 controls) in their GWAS were not publicly released, and we thus used the results in the remaining samples (including 59,851 cases and 113,154 controls) to make this figure via LocusZoom. Intriguingly, in this smaller dataset, rs12129573 is still the leading variation in the 1p31.1 area showing genome-wide significant association with MDD (p = 5.45 × 10−9).

To examine if rs12129573 exerted regulatory effects in human organs other than the brain, we then retrieved RNA-sequencing data of multiple human tissues from the GTEx dataset [28]. This tissue-wide analysis showed that rs12129573 was significantly associated with LINC01360 expression in human testis (N = 322 subjects, p = 1.30 × 10−60, Fig. 2a), and a detailed examination found that its risk A-allele indicated a higher RNA level of the lncRNA. The GTEx tissue-wide analysis did not reveal any significant eQTL associations in other tissues. By contrast, rs12129573 was not associated with the mRNA expression of other genes near LINC01360 at 1p31.1 in the testis, such as LRRIQ3 (>700-Kb far from rs12129573) or NEGR1 (>1-Mb far from rs12129573) (p > 0.4, Fig. S2). According to the RNA-sequencing data from GTEx dataset [28], LINC01360 is preferably expressed in human testis (Fig. S3). To examine the possibility that the relatively rare presence of LINC01360 expression in the GTEx dataset was resulted from limitations of RNA-sequencing techniques, we then conducted semi-quantitative PCR to examine the RNA expression of LINC01360 in human brain tissues (Fig. S4) and several human cell lines (HEK293T, U251, and HCC1806, as shown in the following sections). However, the expression levels of LINC01360 in these samples and cells were quite low.

Fig. 2. Molecular characterization of the linked rs12129573 and rs70959274.

a Expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analyses of rs12129573 with LINC01360 RNA expression in GTEx dataset. b Electrophoresis of Alu polymorphism (rs70959274) different genotypes. c Sanger sequencing of individual carrying heterozygote at the Alu polymorphism (rs70959274). d–f DNA methylation status of the CpG sites within the 351-bp Alu sequence at rs70959274 in HEK293T, U251 and SH-SY5Y cells respectively. [Each row means one clone in bisulfite sequencing; the black solid circle donates unmethylation, and empty circle donates methylation].

Functional prediction analysis of rs12129573 LD linked SNPs

To pinpoint the genetic variation(s) conferring functional impact within this locus, we retrieved information of SNPs in high LD (r2 ≥ 0.8) with rs12129573 in Europeans. Briefly, 170 SNPs were in high LD with rs12129573 in Europeans, and all the 171 SNPs were in the noncoding regions near LINC01360. We therefore performed functional prediction of these SNPs using HaploReg v4.1 dataset [31]. However, we found that they unlikely resided in any DNA segments with open-chromatin peaks or transcription factors binding sites or histone markers in the brain (e.g., H3K4me1, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, and H3K27ac) (Fig. S5). Further functional prediction using other programs (e.g., GWAVA [33], Table S2) also suggested that these SNPs were unlikely functional, as the functional prediction scores of almost all SNPs were <0.5 (prediction scores from three different versions of the classifier (Region score, TSS score, Unmatched score) range 0–1, and higher scores indicate a greater likelihood that the respective variations are functional). In addition, we also utilized data from recently published studies to assess whether any of the 171 SNPs located in the open chromatin peaks in human brain tissues or neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC), so as to examine whether these SNPs exert functions in early neurodevelopment [11, 49]. However, none of the tested SNPs were overlapped with the open chromatin peaks (data not shown).

Identification of a human-unique Alu insertion polymorphism (rs70959274) in strong LD with rs12129573

Although the functional SNPs in the 1p31.1 region and the LINC01360 locus remain unclear, we have identified a 351-bp Alu insertion polymorphism (rs70959274) in 431-bp 3′ downstream of rs12129573, which was further confirmed using in silico analysis on the UCSC website (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and through Sanger DNA sequencing of the target region (Fig. 2b, c). Intriguingly, Alu polymorphisms in strong LD with GWAS risk SNPs of complex diseases have been repeatedly highlighted, and are thought to play putative roles in the pathogenesis of these diseases [14]. We therefore amplified rs70959274 and rs12129573 in 135 Han Chinese individuals, and found that the MDD risk A-allele of rs12129573 was almost completely linked with “absence” of the Alu insertion (r2 = 0.94). In 36 European and 20 Pakistani individuals, the substantial LD between rs12129573 and rs70959274 was also observed (r2 = 0.89 and 1.00, respectively). Considering that Alu elements are usually conserved in primates [20], we then examined rs70959274 across species and found that it was human-specific. Further characterization of its allelic status in multiple human cell lines revealed homozygous presence of the Alu insertion in U251 and SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma) cells, heterozygous in HEK293T cells, and homozygous absence in HCC1806 cells (Fig. S6). However, the Alu polymorphism rs70959274 was not covered in the current GWAS platforms or in public eQTL datasets. Given the tight LD between rs12129573 and rs70959274, we used the genotype of rs12129573 as the proxy of that of rs70959274, and predicted that the presence of the Alu insertion at rs70959274 was linked with a lower RNA level of LINC01360.

Alu insertion at rs70959274 decreases promoter activities in vitro

Compared with single base-pair substitution (i.e., rs12129573), the 351-bp Alu insertion polymorphism (i.e., rs70959274) likely exerts a greater impact in the genome. Indeed, Alu insertions have been demonstrated to affect transcription and post-transcription processes through affecting promoter activity, DNA methylation, alternative splicing, and RNA editing [50]. We therefore tested the regulatory effect of the Alu insertion on promoter activities using an in vitro reporter gene assay. We amplified the DNA fragments spanning rs70959274 from individuals carrying different genotypes of this Alu polymorphism. These sequences were then sub-cloned into the pGL3 promoter vector and transiently co-transfected with an internal control reporter pRL-TK into human HEK293T, U251, and HCC1806 cells. The luciferase activities of these cells were then examined. In all three cells, the transcriptional activity of the pGL3 promoter containing the Alu insertion was significantly lower than that of the promoter without the insertion (p = 1.36 × 10−5 in HEK293T cells, p = 0.01 in U251 cells, and p = 0.001 in HCC1806 cells, two-tailed t-test, Fig. 3a–c), suggesting that the Alu insertion at this locus likely exerted repressive effects on transcription, which is also consistent with the eQTL analysis in human tissues.

Fig. 3. Effects of rs70959274 on LINC01360 transcriptional activities and gene expression.

a–c Results of the reporter gene assay testing the regulatory activities of rs70959274 in HEK293T, U251, and HCC1806 cell lines. Effects of rs70959274 allele variation on pGL3 promoter activity are shown in the panels for HEK293T, U251, and HCC1806 cells. “Negative control” means pGL3 basic empty vector (which does not have promoter activity). “Empty pGL3 vector” means pGL3 promoter empty vector (which has an internal promoter). The Y-axis values represent fold changes of luciferase activity relative to the “Empty pGL3 vector” group. The means and standard deviations of at least four biological replicates are shown. #p ≤ 0.05; *p ≤ 0.01; **p ≤ 0.001; ***p ≤ 0.0001. d–f Semi-quantitative PCR of LINC01360 RNA in HEK293T, U251 and HCC1806 cell lines with and without CRISPR/Cas9 deletion of the DNA sequence spanning Alu insertion at rs70959274 (or flanking sequence only). [Control 1–3 and Alu del 1–3 respectively refer the three biological replicates in which the Alu insertion elements were either not deleted or deleted]. For the semi-quantitative PCR of LINC01360 in HEK293T and HCC1806 cells, the gel electrophoresis figure using the first pair of primer for LINC01360 was presented, and the semi-quantitative PCR using the send pair of primer yielded similar and consistent results (data not shown). For the gel electrophoresis figure in U251 cells, the semi-quantitative PCR of LINC01360 using the first pair of primer did not observe any bands even after the Alu sequence was deleted (data not shown). We then used the second pair of primer which is predicted to cover majority of the LINC01360 transcripts, and the gel electrophoresis is presented in the figure. Therefore, LINC01360 likely underwent distinct alternative splicing patterns in different cells despite all expressed in low level, and LINC01360 transcripts measured by the first pair of primer was not expressed in U251 cells. Alu del, deletion of Alu insertion.

Alu insertion at rs70959274 contains multiple DNA methylation sites

To explore the mechanisms underlying this repressive effect of the Alu insertion on transcriptional activities, we tested whether the Alu element could bind transcription repressors, or underwent hyper-methylation of the DNA. Since rs70959274 has multiple similar sequences across the genome, the current genome-wide sequencing based on short reads (such as ChIP-Seq on H3K4me1, H3K4me3 or transcription factors etc.) is not able to precisely map to the Alu region (Fig. S7). A functional prediction of the 351-bp Alu insertion sequence at rs70959274 did not identify any particular transcription repressors of interest using AliBaba 2.1 program (http://gene-regulation.com/pub/programs/alibaba2/index.html), JASPAR (http://jaspar.genereg.net/) [51], or AnimalTFDB (v3.0) (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/AnimalTFDB/#!/) [52] (Fig. S8). Intriguingly, we identified 23 CpG sites and one CpG island (CGI) within the 351-bp Alu insertion sequence, and bisulfite sequencing further found that all 23 CpG sites in HEK293T and U251 cells were completely or near completely methylated under natural condition (Fig. 2d, e). Similarly, hypermethylation of the Alu insertion at rs70959274 was also observed in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 2f).

Deletion of the Alu insertion (rs70959274) in cells increases RNA expression of LINC01360

We further tested whether the Alu insertion at rs70959274 repressed the RNA expression of LINC01360. We used a dual sgRNA-directed CRISPR/Cas9 system to knock out this Alu element in HEK293T and U251 cells, and then examined the alterations of LINC01360. Since rs70959274 is a short stretch of repetitive DNA sequences, and Alu elements generally have abundant presence of similar sequences in the genome, it is difficult to precisely delete the Alu insertion at rs70959274. To resolve this problem, we designed the sgRNAs that could delete the 1278-bp DNA sequence covering rs70959274. After CRISPR/Cas9-directed genome editing in cells, we examined 28 most likely off-target sites; 22 sites did not have any cleavage signals, and 6 sites had detectable cleavage bands, but further verification of these sites using Sanger sequencing did not find genomic DNA cleavage within 100-bp around each site (Fig. S9 and Table S3). Taken together, significant off-target signals were not detected in this CRISPR/Cas9-directed editing experiment.

Following CRISPR/Cas9 editing, clones with and without the Alu element were selected in triplicates and expanded from HEK293T and U251 cells. Through semi-quantitative PCR, we found that the RNA level of LINC01360 was significantly increased after the Alu insertion was deleted in both HEK293T and U251 cells (Fig. 3d, e). By contrast, mRNA expression of LRRIQ3 or NEGR1 was not altered after the CRISPR/Cas9 editing (Fig. S10).

Since the Alu insertion sequence (351-bp) was difficult to precisely target through CRISPR/Cas9 due to the presence of multiple homological sequences, we deleted both the Alu insertion and two segments of flanking sequences (i.e., a total of 1278-bp). To exclude the possibility that the alteration of LINC01360 after genome editing was solely caused by deletion of the flanking sequence, we performed CRISPR/Cas9 editing in the HCC1806 cells (the genotype at rs70959274 is “totally absent of Alu insertion” in these cells) using the same plasmids to delete these flanking sequences around rs70959274 (i.e., 928-bp). Deleting these flanking sequences in HCC1806 cells did not alter expression of LINC01360, LRRIQ3 or NEGR1 (Figs. 3f and S11).

Deletion of the Alu insertion (rs70959274) in cells alters expression of genes and biological processes relevant to MDD

We then conducted the RNA-sequencing analysis of the HEK293T and U251 cells respectively with and without CRISPR-mediated deletion of the Alu insertion (n = 3 per condition) to identify genes exhibiting significantly different expression levels. In the HEK293T cells, 389 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with an absolute fold change (FC) > 1.20 (|log2(FC) | > 0.26) at an FDR < 0.05 between different genotypic groups were defined (Table S4). Among these genes, 200 DEGs had significantly lower mRNA levels and 189 DEGs had higher expression following the deletion of the Alu insertion. These DEGs were enriched in pathways related to ribosome and biosynthesis of amino acids (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 4a and Table S5). Specifically, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) indicated that these DEGs were significantly enriched in the GO terms “ribosome biogenesis”, “mitochondrial translation”, “mitochondrial gene expression”, and “establishment of protein localization to mitochondrion” (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 4a and Table S6).

Fig. 4.

KEGG pathway and GO biological processes analyses of dysregulated genes in the HEK293T and U251 cell lines after CRISPR/Cas9 deletion of the Alu insertion at rs70959274.

In U251 cells, 132 genes exhibited significantly altered expression levels in cells with Alu insertion deleted compared with the wild-type cells (|log2(FC) | > 0.26 at an FDR < 0.05), among which 47 DEGs were down-regulated and 85 DEGs were upregulated following the Alu insertion deletion (Table S7). KEGG pathway analyses revealed significantly enriched signals in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, focal adhesion, regulation of actin cytoskeleton, cell cycle and axon guidance (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 4a and Table S8). More intriguingly, GSEA results indicated that these DEGs were strongly enriched in the GO terms “positive regulation of neurogenesis”, “learning or memory”, “modulation of chemical synaptic transmission”, “regulation of trans-synaptic signaling” and “regulation of stem cell proliferation” etc. (FDR < 0.05, Fig. 4a and Table S9). Besides highlighting essential pathways, RNA-sequencing analysis in U251 cells also revealed some DEGs whose involvement in MDD were supported by particularly strong evidence, such as FLOT1 and DRD2. FLOT1 has been implicated as a MDD susceptibility gene in a recent integrative analysis of GWAS and RNA-sequencing eQTL transcriptomes, and the mRNA expression of FLOT1 was significantly upregulated in the brain and peripheral blood of MDD patients compared with controls [53]. In a recent GWAS of depression, DRD2 was genome-wide significantly associated with the illness (lowest p = 3.57 × 10−39 for rs61902811 in 660,418 cases and 1,453,489 controls) [2], and dysregulation of the dopamine system has been repeatedly discussed in the pathophysiology of depression [54, 55]. Both FLOT1 and DRD2 showed elevated mRNA expression after deletion of the Alu insertion (which corresponds to higher genetic risk) in the RNA-sequencing analysis (FLOT1, log2(FC) = 0.39, FDR = 0.00934; DRD2, log2(FC) = 0.63, FDR = 0.000858; Fig. S12). The current study provides extra evidence suggesting their pivotal roles in MDD pathogenesis.

Overall, results in both cell lines supported certain pathological hypotheses. For example, abnormal mitochondrial function has been reported in MDD [56–58], although the exact mechanisms linking mitochondrial abnormalities to MDD remain unclear, transcriptomic results in HEK293T cells may provide some insights. Additionally, synaptic dysregulation and impaired learning or memory have been proposed to facilitate MDD pathogenesis [59–63], which is also confirmed in the current transcriptome analysis results in U251 cells. However, there were only six DEGs (EHD1, C15orf39, DCTPP1, PLK2, HSPB1, RRS1) highlighted in both HEK293T and U251 cells (Table S10), and these overlapped genes were not enriched in any biological processes or pathways using the currently available pathway analysis platforms.

Discussion

Chromosome 1p31.1 is a lead risk locus identified by MDD GWAS [4]. Here we identify a human-unique Alu insertion in this genomic region in strong LD with the MDD risk SNP rs12129573, and this Alu insertion acts as a silencer likely through DNA methylation mechanisms. Intriguingly, recent studies have also found altered DNA methylation of the AluY subfamily and long interspersed nuclear element (LINE-1) in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [64, 65]. Therefore, consistent evidence supports the involvement of such mobile retrotransposon elements in psychiatric disorders.

Given that psychiatric disorders are usually considered primarily or dominantly originated from humans (although they appear to decrease Darwinian fitness), there has long been the hypothesis of potential evolutionary mechanisms underlying these illnesses, and many studies have proposed that psychiatric disorders might be relevant to certain human-unique features (e.g., DNA alleles, gene expression, and protein function). For example, we have previously identified a human-specific allele that undergoes Darwinian natural selection. This allele enables humans to adapt to a colder environment in Europe, while simultaneously increases the risk of schizophrenia [66]. A previous study discovered a human-specific tandem repeat in the AS3MT gene increasing risk of psychiatric disorders in human populations [19]. In addition, we previously reported that the primate-specific gene BTN3A2 was a schizophrenia risk gene in the MHC loci [12], and have also recently characterized two human-specific Alu polymorphisms in the GWAS risk loci of psychiatric disorders at 10q24.32 and 3p21.1 respectively, and the “presence” of the Alu insertion at each locus has been recognized as psychiatric risk alleles [17, 18]. Intriguingly, the human-unique alleles at these previously reported psychiatric risk loci all indicate higher risk of psychiatric disorders, supporting the putative origination of psychiatric illnesses in humans. However, there is never an easy answer to etiology of psychiatric illnesses from the perspective of evolution. As mentioned, these diseases and variations are considered to decrease Darwinian fitness (e.g., they result in substantial reproductive disadvantage). Although there have been multiple evolutionary hypothesis (e.g., natural selection hypothesis, mutation-selection-drift hypothesis, and balancing selection hypothesis) discussing why psychiatric disorders and their risk genetic variations still exist in humans, a satisfactory and validated explanation is still lacking [67, 68]. Indeed, we herein have identified a new psychiatric risk locus whose human-unique allele (i.e., Alu insertion) reduced the genetic risk of MDD. This result thus suggests the complexity of the genetic and evolutionary basis of MDD. Considering that numerous genetic variations have pleiotropic effects in human traits, it is possible that MDD is significantly affected by the interactions between environmental exposures and genetic variations, and both evolutionary ancestral and novel alleles at distinct loci may confer risk of this illness.

We have also defined a lncRNA (LINC01360) whose expression is affected by the rs70959274 Alu polymorphism. Therefore, this lncRNA likely plays a role in the pathogenesis of MDD. Nevertheless, the caveats still exist regarding LINC01360 in the present study. Although our results strongly suggest the involvement of this lncRNA in the genetic risk of MDD related to rs12129573 and the rs70959274 Alu polymorphism, we are not able to comprehensively characterize its expression pattern in tissues relevant to MDD (e.g., the brain) using currently available data (Fig. S1) [28]. Instead, our spatial expression analysis shows that LINC01360 is preferably expressed in human testis, suggesting its putative function in spermatogenesis and testosterone production, etc. With little knowledge of the link between testis and MDD, the mechanisms by which LINC01360 participate in MDD remain unclear. Nevertheless, testosterone has been implicated in the pathophysiology and treatment of MDD before. For example, Giltay et al. [69] found that plasma testosterone levels were lower in men with MDD compared with healthy men, and Walther et al. [70] reported that testosterone treatment might to be effective and efficacious in reducing depressive symptoms in men. Therefore, further studies exploring whether LINC01360 affects MDD via modulating testosterone production or function are of great interest.

It is also worth noting that the current failure to detect LINC01360 expression in brain tissues might not be sufficient to deny its potential function in the brain. Specifically, the GTEx RNA-sequencing data [28] used in the current study is primarily obtained from postnatal brain tissues. As accumulating studies suggest that some genetic risk factors of psychiatric illnesses exert functional impact during particular stages of brain development [71–73], whether the expression of LINC01360 peaks in the brain during a specific time-window that is not covered in the current dataset remains an interesting question to answer. In addition, it is gradually recognized that gene expression profiles of different types of cells in the brain differ significantly [74, 75]. Since the data used to examine LINC01360 expression in the present study does not differentiate different types of cells, it is possible that its expression is altered only in certain cells, and the differences are therefore undetectable when data from all cells are analyzed together. As a result, we believe that quantifying LINC01360 expression in different cells in the brain during different developmental stages may provide valuable information regarding its functionality.

We have confirmed the functional impact of the rs70959274 Alu polymorphism through CRISPR/Cas9-directed genomic editing in cells. The regulatory effect of rs70959274 on LINC01360 promoter activities are consistent in different cell lines, providing valuable insights into the functional impact of this Alu polymorphism. However, caution is also needed regarding the inconsistent RNA-sequencing results between HEK293T and U251 cells following deletion of the rs70959274 Alu insertion. For example, the risk genes highlighted in U251 cells, such as FLOT1 and DRD2, were not altered in HEK293T cells; and we have observed alteration of mitochondrial-relevant pathways following genomic editing in HEK293T cells only. Therefore, we speculate that the Alu insertion and the lncRNA might exert (partially) distinct functions between HEK293T and U251 cells, as reflected in the RNA-sequencing analysis. In addition, previous studies have reported enriched Alu content in the mitochondrial genes, which might disrupt the neuronal mitochondrial homeostasis and lead to brain disorders [76], it is thus also possible that the altered mitochondrial pathway genes in HEK293T cell after deletion of the Alu insertion at rs70959274 is not related to LINC01360, but rather because of other undefined mechanisms.

In summary, our study has described the potential involvement of a novel human-specific Alu polymorphism in the genetic risk of MDD conferred by the 1p31.1 locus, and emphasizes the necessity and importance of considering repetitive DNA polymorphisms in studying psychiatric illnesses. We also reveal that a lncRNA, LINC01360, is likely modulated by this Alu polymorphism. While the exact role of LINC01360 in MDD remains unclear, further studies characterizing its expression and function in MDD-relevant tissues at different developmental stages are urgently needed to gain insights into the etiology and pathogenesis of this illness. In addition, it is well-known that DRD2 is a schizophrenia risk gene, and in previous GWAS study, the LINC01360 locus also exhibited genome-wide significant association with schizophrenia (rs12129573, p = 8.94 × 10−15 in 40,675 cases and 64,643 controls) [77], therefore our investigations on the Alu polymorphism and LINC01360 may also provide insights into the biological mechanisms of schizophrenia albeit further characterization study should be performed.

Funding and disclosure

We sincerely acknowledge with appreciation all the individuals with major depressive disorders and healthy controls whose contributions made this work possible. We are deeply grateful to all the participants as well as to the physicians working on this project. We thanks Prof. Ceshi Chen’s lab at Kunming Institute of Zoology for providing the HCC1806 cells. This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (81722019 to M.L., 81671330 and 81971252 to L.L.); the Innovative Research Team of Science and Technology department of Yunnan Province (2019HC004); Open Program of Henan Key Laboratory of Biological Psychiatry (ZDSYS2018001 to H.C.); High Scientific and Technological Research Fund of Xinxiang Medical University (2017ZDCG-04 to L.L.); The training plan for young excellent teachers in Colleges and Universities of Henan (2016GGJS-106 to W.L.); The Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (192102310086 to W.L.), and the Strategic Priority Research Program (B) of CAS (XDB32020200 to Y.G.Y.). Xiao Xiao was also supported by the CAS Western Light Program, and Youth Innovation Promotion Association, CAS. Ming Li was also supported by CAS Pioneer Hundred Talents Program and the 1000 Young Talents Program. Data were generated as part of the CommonMind Consortium supported by funding from Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd and NIH grants R01MH085542, R01MH093725, P50MH066392, P50MH080405, R01MH097276, RO1-MH-075916, P50M096891, P50MH084053S1, R37MH057881 and R37MH057881S1, HHSN271201300031C, AG02219, AG05138 and MH06692. Brain tissue for the study was obtained from the following brain bank collections: the Mount Sinai NIH Brain and Tissue Repository, the University of Pennsylvania Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center, the University of Pittsburgh NeuroBioBank and Brain and Tissue Repositories and the NIMH Human Brain Collection Core. CMC Leadership: Pamela Sklar, Joseph Buxbaum (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai), Bernie Devlin, David Lewis (University of Pittsburgh), Raquel Gur, Chang-Gyu Hahn (University of Pennsylvania), Keisuke Hirai, Hiroyoshi Toyoshiba (Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Limited), Enrico Domenici, Laurent Essioux (F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd), Lara Mangravite, Mette Peters (Sage Bionetworks), Thomas Lehner, Barbara Lipska (NIMH).

Supplementary information

Author contributions

W.L., L.L., X.X. and M.L. designed the study and interpreted the results. W.L., W.L., X.C. and Z.Y. conducted the SNP and Alu genotyping, the primary functional assays, including molecular cloning, cell line experiments, and analysis of those data. H.L. performed the bioinformatics analysis based on RNA-sequencing data. H.C. and X.X. contributed to design the CRISPR/Cas9 experiments. W.L., X.S., M.S., D.S.Z., X.L., C.Z., M.S., L.Z., Y.Y., Y.Z., J.Z., Y.G.Y., Y.F. and L.L. contributed to collection of clinical samples. X.X. and M.L. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to the final version of the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Weipeng Liu, Wenqiang Li, Xin Cai, Zhihui Yang

Contributor Information

Luxian Lv, Email: lvx928@126.com.

Ming Li, Email: limingkiz@mail.kiz.ac.cn.

Xiao Xiao, Email: xiaoxiao2@mail.kiz.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41386-020-0659-2).

References

- 1.Sullivan PF, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Genetic epidemiology of major depression: review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1552–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke TK, Hafferty JD, Gibson J, Shirali M, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:343–52. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Luo Z, Gu C, Hall LS, McIntosh AM, Zeng Y, et al. Common variants on 6q16.2, 12q24.31 and 16p13.3 are associated with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:2146–53. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M, Trzaskowski M, Byrne EM, Abdellaoui A, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet. 2018;50:668–81. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li M, Yue W. VRK2, a candidate gene for psychiatric and neurological disorders. Mol Neuropsychiatry. 2018;4:119–33. doi: 10.1159/000493941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Chang H, Song X, Liu W, Li L, Wang L, et al. Integrative analyses of major histocompatibility complex loci in the genome-wide association studies of major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1552–61. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards SL, Beesley J, French JD, Dunning AM. Beyond GWASs: illuminating the dark road from association to function. Am J Hum Genet. 2013;93:779–97. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visscher PM, Wray NR, Zhang Q, Sklar P, McCarthy MI, Brown MA, et al. 10 years of GWAS discovery: biology, function, and translation. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;101:5–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duan J, Shi J, Fiorentino A, Leites C, Chen X, Moy W, et al. A rare functional noncoding variant at the GWAS-implicated MIR137/MIR2682 locus might confer risk to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:744–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huo Y, Li S, Liu J, Li X, Luo XJ. Functional genomics reveal gene regulatory mechanisms underlying schizophrenia risk. Nat Commun. 2019;10:670. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08666-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest MP, Zhang H, Moy W, McGowan H, Leites C, Dionisio LE, et al. Open chromatin profiling in hiPSC-derived neurons prioritizes functional noncoding psychiatric risk variants and highlights neurodevelopmental loci. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21:305–18 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y, Bi R, Zeng C, Ma C, Sun C, Li J, et al. Identification of the primate-specific gene BTN3A2 as an additional schizophrenia risk gene in the MHC loci. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:530–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang CP, Li X, Wu Y, Shen Q, Zeng Y, Xiong Q, et al. Comprehensive integrative analyses identify GLT8D1 and CSNK2B as schizophrenia risk genes. Nat Commun. 2018;9:838. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payer LM, Steranka JP, Yang WR, Kryatova M, Medabalimi S, Ardeljan D, et al. Structural variants caused by Alu insertions are associated with risks for many human diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E3984–E92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704117114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song JHT, Lowe CB, Kingsley DM. Characterization of a human-specific tandem repeat associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;103:421–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marshall CR, Howrigan DP, Merico D, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Wu W, Greer DS, et al. Contribution of copy number variants to schizophrenia from a genome-wide study of 41,321 subjects. Nat Genet. 2017;49:27–35. doi: 10.1038/ng.3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang Z, Zhou D, Li H, Cai X, Liu W, Wang L, et al. The genome-wide risk alleles for psychiatric disorders at 3p21.1 show convergent effects on mRNA expression, cognitive function and mushroom dendritic spine. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:48–66. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang Z, Cai X, Qu N, Zhao L, Zhong BL, Zhang SF, et al. Identification of a functional 339-bp Alu polymorphism in the schizophrenia-associated locus at 10q24.32. Zool Res. 2020;41:84–9. doi: 10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2020.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M, Jaffe AE, Straub RE, Tao R, Shin JH, Wang Y, et al. A human-specific AS3MT isoform and BORCS7 are molecular risk factors in the 10q24.32 schizophrenia-associated locus. Nat Med. 2016;22:649–56. doi: 10.1038/nm.4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deininger P. Alu elements: know the SINEs. Genome Biol. 2011;12:236. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-12-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stoneking M, Fontius JJ, Clifford SL, Soodyall H, Arcot SS, Saha N, et al. Alu insertion polymorphisms and human evolution: evidence for a larger population size in Africa. Genome Res. 1997;7:1061–71. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.11.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang C, Wu Z, Zhao G, Wang F, Fang Y. Identification of IL6 as a susceptibility gene for major depressive disorder. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31264. doi: 10.1038/srep31264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao X, Zheng F, Chang H, Ma Y, Yao YG, Luo XJ, et al. The Gene Encoding Protocadherin 9 (PCDH9), a novel risk factor for major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:1128–37. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aljanabi SM, Martinez I. Universal and rapid salt-extraction of high quality genomic DNA for PCR-based techniques. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4692–3. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.22.4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Luo XJ, Xiao X, Shi L, Liu XY, Yin LD, et al. Analysis of common genetic variants identifies RELN as a risk gene for schizophrenia in Chinese population. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14:91–9. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.587891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2336–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.GTEx Consortium, Laboratory Data Analysis, Coordinating Center-Analysis Working Group, Statistical Methods groups-Analysis Working Group, Enhancing GTEx groups, NIH Common Fund. et al. Genetic effects on gene expression across human tissues. Nature. 2017;550:204–13. doi: 10.1038/nature24277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genomes Project Consortium. Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward LD, Kellis M. HaploReg: a resource for exploring chromatin states, conservation, and regulatory motif alterations within sets of genetically linked variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D930–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Encode Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ritchie GR, Dunham I, Zeggini E, Flicek P. Functional annotation of noncoding sequence variants. Nat Methods. 2014;11:294–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wingender E, Dietze P, Karas H, Knuppel R. TRANSFAC: a database on transcription factors and their DNA binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:238–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larsen F, Gundersen G, Lopez R, Prydz H. CpG islands as gene markers in the human genome. Genomics. 1992;13:1095–107. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90024-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haeussler M, Schonig K, Eckert H, Eschstruth A, Mianne J, Renaud JB, et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 2016;17:148. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-1012-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang H, Yi B, Ma R, Zhang X, Zhao H, Xi Y. CRISPR/cas9, a novel genomic tool to knock down microRNA in vitro and in vivo. Sci Rep. 2016;6:22312. doi: 10.1038/srep22312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao L, Chang H, Zhou DS, Cai J, Fan W, Tang W, et al. Replicated associations of FADS1, MAD1L1, and a rare variant at 10q26.13 with bipolar disorder in Chinese population. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:270. doi: 10.1038/s41398-018-0337-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu W, Yan H, Zhou D, Cai X, Zhang Y, Li S, et al. The depression GWAS risk allele predicts smaller cerebellar gray matter volume and reduced SIRT1 mRNA expression in Chinese population. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:333. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0675-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012;16:284–7. doi: 10.1089/omi.2011.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu G, Li F, Qin Y, Bo X, Wu Y, Wang S. GOSemSim: an R package for measuring semantic similarity among GO terms and gene products. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:976–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jaffe AE, Straub RE, Shin JH, Tao R, Gao Y, Collado-Torres L, et al. Developmental and genetic regulation of the human cortex transcriptome illuminate schizophrenia pathogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1117–25. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0197-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fromer M, Roussos P, Sieberts SK, Johnson JS, Kavanagh DH, Perumal TM, et al. Gene expression elucidates functional impact of polygenic risk for schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1442–53. doi: 10.1038/nn.4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ng B, White CC, Klein HU, Sieberts SK, McCabe C, Patrick E, et al. An xQTL map integrates the genetic architecture of the human brain’s transcriptome and epigenome. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1418–26. doi: 10.1038/nn.4632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fullard JF, Giambartolomei C, Hauberg ME, Xu K, Voloudakis G, Shao Z, et al. Open chromatin profiling of human postmortem brain infers functional roles for non-coding schizophrenia loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26:1942–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hasler J, Strub K. Alu elements as regulators of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5491–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fornes O, Castro-Mondragon JA, Khan A, van der Lee R, Zhang X, Richmond PA, et al. JASPAR 2020: update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:D87–92. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu H, Miao YR, Jia LH, Yu QY, Zhang Q, Guo AY. AnimalTFDB 3.0: a comprehensive resource for annotation and prediction of animal transcription factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D33–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong J, Li S, Zeng W, Li X, Gu C, Liu J, et al. Integration of GWAS and brain eQTL identifies FLOT1 as a risk gene for major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44:1542–51. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0345-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grace AA. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:524–32. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dunlop BW, Nemeroff CB. The role of dopamine in the pathophysiology of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:327–37. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cai N, Chang S, Li Y, Li Q, Hu J, Liang J, et al. Molecular signatures of major depression. Curr Biol. 2015;25:1146–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shao L, Martin MV, Watson SJ, Schatzberg A, Akil H, Myers RM, et al. Mitochondrial involvement in psychiatric disorders. Ann Med. 2008;40:281–95. doi: 10.1080/07853890801923753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang Q, Dwivedi Y. Transcriptional profiling of mitochondria associated genes in prefrontal cortex of subjects with major depressive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2017;18:592–603. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2016.1197423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Penzes P, Cahill ME, Jones KA, VanLeeuwen JE, Woolfrey KM. Dendritic spine pathology in neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:285–93. doi: 10.1038/nn.2741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forrest MP, Parnell E, Penzes P. Dendritic structural plasticity and neuropsychiatric disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:215–34. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duman RS, Aghajanian GK, Sanacora G, Krystal JH. Synaptic plasticity and depression: new insights from stress and rapid-acting antidepressants. Nat Med. 2016;22:238–49. doi: 10.1038/nm.4050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kang HJ, Voleti B, Hajszan T, Rajkowska G, Stockmeier CA, Licznerski P, et al. Decreased expression of synapse-related genes and loss of synapses in major depressive disorder. Nat Med. 2012;18:1413–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duman RS, Aghajanian GK. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science. 2012;338:68–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1222939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li S, Zong L, Hou Y, Zhang W, Zhou L, Yang Q, et al. Altered DNA methylation of the AluY subfamily in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Epigenomics. 2019;11:581–6. doi: 10.2217/epi-2018-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li S, Yang Q, Hou Y, Jiang T, Zong L, Wang Z, et al. Hypomethylation of LINE-1 elements in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;107:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li M, Wu DD, Yao YG, Huo YX, Liu JW, Su B, et al. Recent positive selection drives the expansion of a schizophrenia risk nonsynonymous variant at SLC39A8 in Europeans. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:178–90. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Keller MC. Evolutionary perspectives on genetic and environmental risk factors for psychiatric disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2018;14:471–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050817-084854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Uher R. The role of genetic variation in the causation of mental illness: an evolution-informed framework. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:1072–82. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giltay EJ, van der Mast RC, Lauwen E, Heijboer AC, de Waal MWM, Comijs HC. Plasma testosterone and the course of major depressive disorder in older men and women. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25:425–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Walther A, Breidenstein J, Miller R. Association of testosterone treatment with alleviation of depressive symptoms in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:31–40. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tao R, Cousijn H, Jaffe AE, Burnet PW, Edwards F, Eastwood SL, et al. Expression of ZNF804A in human brain and alterations in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: a novel transcript fetally regulated by the psychosis risk variant rs1344706. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:1112–20. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Birnbaum R, Jaffe AE, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Prenatal expression patterns of genes associated with neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:758–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walker RL, Ramaswami G, Hartl C, Mancuso N, Gandal MJ, de la Torre-Ubieta L, et al. Genetic control of expression and splicing in developing human brain informs disease mechanisms. Cell. 2019;179:750–71 e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kanton S, Boyle MJ, He Z, Santel M, Weigert A, Sanchis-Calleja F, et al. Organoid single-cell genomic atlas uncovers human-specific features of brain development. Nature. 2019;574:418–22. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1654-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhong S, Zhang S, Fan X, Wu Q, Yan L, Dong J, et al. A single-cell RNA-seq survey of the developmental landscape of the human prefrontal cortex. Nature. 2018;555:524–8. doi: 10.1038/nature25980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Larsen PA, Lutz MW, Hunnicutt KE, Mihovilovic M, Saunders AM, Yoder AD, et al. The Alu neurodegeneration hypothesis: a primate-specific mechanism for neuronal transcription noise, mitochondrial dysfunction, and manifestation of neurodegenerative disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:828–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pardinas AF, Holmans P, Pocklington AJ, Escott-Price V, Ripke S, Carrera N, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet. 2018;50:381–9. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.