Abstract

Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma (GPC) is an uncommon primary sinonasal neoplasm showing a perivascular myoid differentiation. Originally perceived as an intranasal counterpart to soft tissue hemangiopericytomas, initial immunohistochemical reports showed mostly negative to focal weak reactivity for CD34 as useful in separating GPC (almost always benign) from morphologic mimics, mainly solitary fibrous tumor (potentially aggressive). In anecdotally encountering cases of GPC with CD34 reactivity beyond the expected weak/negative immunoprofile, we sought to formally evaluate CD34 staining in 10 cases of GPC from two different vendors in conjunction with a meta-analysis of other GPC series reporting CD34 staining. Ten cases of GPC were retrieved from the authors’ pathology archives (left nasal cavity = 7, right nasal cavity = 3; 5 men, 5 women; average age 59.0 years with range of 43–77 years). Follow-up showed no evidence of disease after complete resection from all 10 cases (average follow-up length of 53.3 months, range 6–106 months). All 10 GPC cases (100%) showed positivity using CD34 from Leica (QBend10 clone), with most showing moderate to diffuse staining intensity and moderate extent, while only 2 of 10 cases (20%) showed positivity using CD34 from Ventana (QBend10 clone), with both positive cases showing weak staining intensity and focal extent. Literature review of other studies (reporting ≥ 5 GPC cases) found a wide spectrum of CD34 positivity ranging from 0 to 100%; including our GPC cases, CD34 showed a cumulative positivity of 28%. Although negative CD34 reactivity has been historically regarded as prototypic for GPC, in this study we have exposed laboratory variability in CD34 expression and have shown that reliance on expected negative reactivity in GPC can be a clinically relevant diagnostic pitfall. Our findings suggest a panel approach in selecting diagnostic immunostains rather than relying on CD34 alone in the assessment of spindle cell neoplasms in the sinonasal tract with admixed prominent staghorn-like vasculature.

Keywords: CD34, Glomangiopericytoma, Immunohistochemistry, Hemangiopericytoma, Nasal, Sinonasal

Introduction

Sinonasal glomangiopericytoma (GPC; formerly sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma or hemangiopericytoma-like tumor) was first described in 1976 [1] as a spindle cell neoplasm sharing morphologic features with soft tissue hemangiopericytoma [2], but showing a unique predilection for sinonasal location. Subsequent to this initial morphologic GPC description, the largest immunohistochemical assessment of GPC reported positive staining with smooth muscle actin and weak to negative CD34 staining as helpful diagnostic markers that contrasted with the opposite staining pattern of “true” hemangiopericytoma (most of which are now classified as solitary fibrous tumor) [3]. The distinction between GPC and solitary fibrous tumor is not entirely academic. GPC almost always behaves in a benign manner, while solitary fibrous tumor can behave unpredictably, with some cytologically bland cases behaving aggressively and even metastasizing.

Since this 2003 immunohistochemical study [3], we have anecdotally encountered some cases of GPC with CD34 staining intensity and extent beyond what would typically be expected, including some on small tissue biopsies creating diagnostic confusion, particularly with solitary fibrous tumor. In this study, we sought to investigate CD34 reactivity in our collection of GPC in conjunction with a meta-analysis of other GPC series reporting CD34 staining.

Materials and Methods

Ten cases of GPC were retrieved from the authors’ pathology archives with diagnoses confirmed by both authors in all cases. Clinicopathologic features were noted on all cases with clinical follow-up obtained. Immunohistochemical expression for monoclonal CD34 was assessed using the ready-to-use QBend10 clone from either Leica or Ventana on 1 whole-slide representative section from each case on 4-mm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded freshly cut sections mounted on charged slides and baked at 60 °C for 1 h. Cases were evaluated using either the BOND Polymer Refine detection kit from Leica Microsystems or Ultraview DAB from Ventana BenchMark ULTRA. A separate positive control tissue was used (normal vessels from tonsil or placenta). Membranous/cytoplasmic CD34 staining extent (0 to 3 +) and staining intensity (0 to 3 +) was scored for all cases. Staining extent and intensity were also scored for SMA, beta-catenin, STAT6, pankeratin, and S100 immunostains that were already performed on GPC cases.

Results

The 10 GPC cases were all excisional specimens from left nasal cavity (n = 7) or right nasal cavity (n = 3); one case involved both nasal cavities. GPC cases were from 5 men and 5 women, with an average age of 59.0 years (range 43–77 years). Follow-up obtained from all 10 cases showed no evidence of disease after complete resection (average follow-up length of 53.3 months, range 6–106 months).

All 10 of the GPC cases stained using CD34 from Leica showed positivity (100%), most showing moderate to diffuse staining intensity with moderate staining extent. In contrast, only 2 of 10 cases (20%) showed any positivity using CD34 from Ventana, with weak staining intensity and focal staining extent (Figs. 1 and 2). All 10 GPC cases showed positivity for SMA (100%, mostly strong/diffuse) and for nuclear beta-catenin positivity (100%, strong/diffuse), while STAT6, pankeratin, and S100 were completely negative in all 10 cases (0%; Table 1).

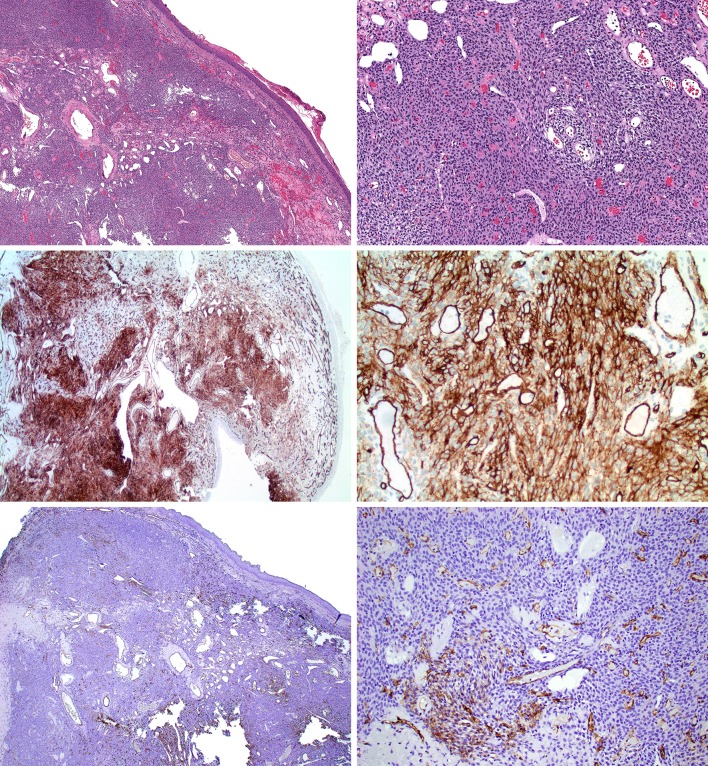

Fig. 1.

Glomangiopericytoma study case 4. (Top row, H&E) Spindled to epithelioid cellular proliferation with admixed staghorn-like vasculature with Grenz zone underlying sinonasal mucosa. (Middle row; CD34 from Leica) Diffuse moderate reactivity for CD34 in lesional cells. (Bottom row; CD34 from Ventana) Patchy weak reactivity for CD34 in lesional cells

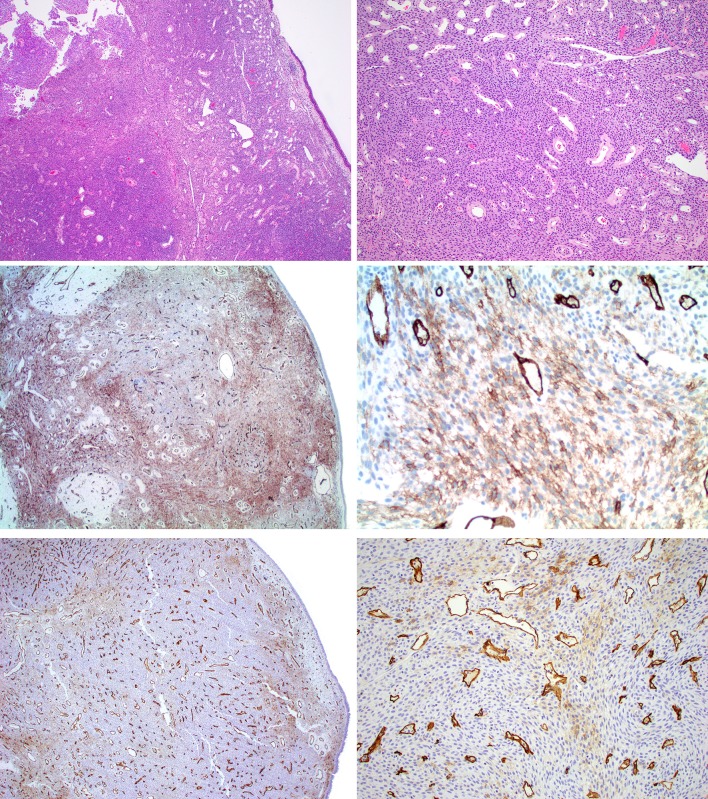

Fig. 2.

Glomangiopericytoma study case 9. (Top row, H&E) Spindled to epithelioid cellular proliferation with admixed staghorn-like vasculature with Grenz zone underlying sinonasal mucosa. (Middle row; CD34 from Leica) Diffuse moderate reactivity for CD34 in lesional cells. (Bottom row; CD34 from Ventana) Patchy weak reactivity for CD34 in lesional cells

Table 1.

Immunoprofile of glomangiopericytoma cases

| Case # | Leica CD34 intensity (0–3 +)/extent (0–3 +) | Ventana CD34 intensity (0–3 +)/extent (0–3 +) | SMA intensity (0–3 +)/extent (0–3 +) | Nuclear beta-catenin intensity (0–3 +)/extent (0–3 +) | STAT6 intensity (0–3 +)/extent (0–3 +) | S100 intensity (0–3 +)/extent (0–3 +) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 +/2 + | 0/0 | 2 +/2 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 2 | 1 +/1 + | 0/0 | 1 +/2 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 3 | 2 +/2 + | 0/0 | 3 +/3 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 4 | 2 +/2 + | 1 +/1 + | 2 +/3 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 5 | 3 +/2 + | 0/0 | 2 +/2 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 6 | 2 +/2 + | 0/0 | 3 +/3 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 7 | 2 +/2 + | 0/0 | 3 +/3 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 8 | 2 +/2 + | 0/0 | 2 +/2 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 9 | 3 +/2 + | 1 +/1 + | 2 +/2 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 10 | 2 +/2 + | 0/0 | 3 +/3 + | 3 +/3 + | 0/0 | 0/0 |

A meta-analysis literature review of previously-published series reporting CD34 immunohistochemical results in GPC (minimum of 5 cases) found 5 studies reporting a wide spectrum of CD34 positivity, ranging from 0 to 100% [3–7] (Table 2). The studies reporting positive CD34 staining in GPC described staining patterns as “weak” and/or “focal” [3, 6], although one study simply reported staining pattern as “variable.” [7] Only 3 of the 5 cases included details regarding CD34 clone used in their study while all but 1 study provided antibody dilution utilized.

Table 2.

Review of CD34 immunohistochemical results for glomangiopericytoma

| Study | Positive cases | Staining pattern | Antibody vendor/clone/dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thompson et al. [3] | 5/60 (8%) | Focal, weak | BioGenex Labs/unspecified clone/1:40 |

| Tse et al. [4] | 0/6 (0%) | None | Becton–Dickinson/My10/unspecified dilution |

| Kuo et al. [5] | 0/5 (0%) | None | Dako/unspecified clone/1:50 |

| Agaimy et al. [6] | 4/6 (67%) | Focal, weak | Immunotech/QBend10/1:200 |

| Lasota et al. [7] | 13/13 (100%) | Variable | Dako/QBend10/1:150 |

| Current | 5/5 (100%) | Mostly moderate, diffuse | Leica/QBend10/ready-to-use |

| Current | 1/5 (20%) | Focal, weak | Ventana/QBend10/ready-to-use |

| Total | 28/100 (28%) |

Conclusions

GPC is an uncommon primary sinonasal neoplasm showing a perivascular myoid differentiation. Initially reported as “hemangiopericytoma-like intranasal tumor,” [1] based on morphology alone, the first large-series immunohistochemical analysis of GPC reported mostly negative staining for CD34, with 8% of positive cases showing only focal, weak reactivity [3]. Subsequent studies corroborated this initial expected negative/weak CD34 reactivity in GPC, while others showed a significantly higher percentage of CD34 positivity (Table 2). Our findings, using the same ready-to-use CD34 clone but from different vendors, similarly demonstrated a wide range of positivity in GPC ranging from 20 to 100%, notably including mostly diffuse, moderate positivity with the CD34 antibody from Leica. Including our GPC cases with those (n ≥ 5 cases) previously-published, CD34 showed a cumulative positivity of 28% (Table 2). Of note, the QBend CD34 clone shows higher sensitivity (79%) than non-QBend clones (8%; excluding data from single study not including clone description).

While the goal of this study was not to provide a complete review of the complex principles of diagnostic immunohistochemistry, it should be noted that issues related to the tissue (fixation), slide preparation (sectioning, mounting, drying), or immunohistochemical platform (antigen retrieval, detection, blocking, counterstaining) are just some of the variables which may be attributable to the wide differences in CD34 positivity. Another less familiar potential source of variability involves initial validation of CD34 antibody. In some labs, a unique orderable CD34 immunostain is available in the work-up of hematolymphoid neoplasms versus soft tissue tumors, both of which have undergone separate validations and titrations.

The importance of recognizing laboratory variability of CD34 expression in GPC demonstrated by this study rests on avoiding reliance of the “expected” CD34 negative immunoprofile as diagnostic for GPC. In most cases, morphologic features including intact surface epithelium and a Grenz zone overlying a cellular, syncytial proliferation of spindled to epithelioid cells with intimately admixed staghorn-like vessels with perivascular hyalinization are sufficient in accurately diagnosing GPC. When confirmatory immunohistochemistry is needed, the “myoid” phenotype can be demonstrated with positivity for SMA. However, particularly on small sinonasal biopsy samples, obtaining a CD34 positive/SMA positive result adds solitary fibrous tumor as another plausible diagnostic consideration. Although the addition of nuclear beta-catenin immunoreactivity was initially touted as a useful marker for GPC [7], a follow-up study demonstrated poor specificity for nuclear beta-catenin, showing reactivity in GPC, solitary fibrous tumor, and also synovial sarcoma and even biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma [8]. As such, reliance on STAT6 immunostain (surrogate marker of NAB2-STAT6 fusion typically seen in solitary fibrous tumor [9, 10]) is most helpful distinguishing solitary fibrous tumor from GPC [6]. Table 3 lists the key differential diagnostic considerations from GPC, emphasizing a panel-approach to immunohistochemistry.

Table 3.

Key differential diagnosis for glomangiopericytoma and suggested immunohistochemical panel

| Benign/borderline tumors | Suggested immunoprofile |

|---|---|

| Glomangiopericytoma | SMA+, STAT6-, TLE1-, CD31-, CD117-, SOX10-, S100-, EMA- |

| Solitary fibrous tumor | STAT6+, TLE1- |

| Myopericytoma | Nuclear beta catenin-, STAT6-, TLE1- |

| Lobular capillary hemangioma | CD31+, SMA-, STAT6-, TLE1- |

| Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma | CD117+, AR+, SMA-, STAT6-, TLE1- |

| Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor | SOX10+, S100+, STAT6-, TLE1- |

| Meningioma | EMA+, PR+, STAT6-, TLE1- |

| Malignant tumors | Suggested immunoprofile |

|---|---|

| Monophasic synovial sarcoma | TLE1+, STAT6-, SOX10-, S100- |

| Biphenotypic sinonasal sarcoma | PAX3+, S100+, SMA+, SOX10-, STAT6-, TLE1- |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | SOX10+, S100+, STAT6-, TLE1-, INI1- (epithelioid type), h3k27me3- |

| Melanoma | SOX10+, S100+, STAT6-, TLE1- |

All 10 of our GPC cases showed no evidence of disease after complete resection, consistent with regarded indolent behavior for these tumors [11]. Interestingly, one review evaluating various clinicopathologic characteristics of GPC reported “negative staining for CD34” as an independent prognostic indicator significant to overall survival [12]. Although this meta-analysis did not provide details on CD34 staining cut-offs to constitute positive versus negative cases, and while we are not aware our clinicians using CD34 status in making management decisions in GPC, in light of the findings from our study, extrapolating any diagnostic or prognostic findings based on CD34 staining result should be done cautiously.

In summary, although negative CD34 reactivity has been historically regarded as prototypic for GPC, in this study we have exposed laboratory variability in CD34 expression and have shown that reliance on expected negative reactivity in GPC can be a diagnostic pitfall, especially on small tissue samples. Our findings suggest a panel-approach in selecting diagnostic immunostains rather than relying on CD34 alone in the assessment of spindle cell neoplasms in the sinonasal tract with admixed prominent staghorn-like vasculature.

Funding

This study was funded, in part, by the Jane B. and Edwin P. Jenevein M.D. Endowment in Pathology at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Compagno J, Hyams VJ. Hemangiopericytoma-like intranasal tumors A clinicopathologic study of 23 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1976;66(4):672–683. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/66.4.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stout AP, Murray MR. Hemangiopericytoma: a vascular tumor featuring zimmermann’s pericytes. Ann Surg. 1942;116(1):26–33. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194207000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson LD, Miettinen M, Wenig BM. Sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 104 cases showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(6):737–749. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tse LL, Chan JK. Sinonasal haemangiopericytoma-like tumour: a sinonasal glomus tumour or a haemangiopericytoma? Histopathology. 2002;40(6):510–517. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuo FY, Lin HC, Eng HL, Huang CC. Sinonasal hemangiopericytoma-like tumor with true pericytic myoid differentiation: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of five cases. Head Neck. 2005;27(2):124–129. doi: 10.1002/hed.20122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agaimy A, Barthelmeß S, Geddert H, et al. Phenotypical and molecular distinctness of sinonasal haemangiopericytoma compared to solitary fibrous tumour of the sinonasal tract. Histopathology. 2014;65(5):667–673. doi: 10.1111/his.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasota J, Felisiak-Golabek A, Aly FZ, Wang ZF, Thompson LD, Miettinen M. Nuclear expression and gain-of-function β-catenin mutation in glomangiopericytoma (sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma): insight into pathogenesis and a diagnostic marker. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(5):715–720. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jo VY, Fletcher CDM. Nuclear β-catenin expression is frequent in sinonasal hemangiopericytoma and its mimics. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(2):119–123. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0737-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, Mertens F, Hornick JL. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol. 2014;27(3):390–395. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2013.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Ohno M, et al. STAT6 immunohistochemistry is helpful in the diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38(4):552–559. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson L, Flucke U, Wenig M, et al. Sinonasal Glomangiopericytoma. In: El-Naggar A, Chan J, Grandis J, et al., editors. WHO classification of head and neck tumors. 4. Lyon: IARC Press; 2017. pp. 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park ES, Kim J, Jun SY. Characteristics and prognosis of glomangiopericytomas: a systematic review. Head Neck. 2017;39(9):1897–1909. doi: 10.1002/hed.24818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]