Abstract

Neurofibromas rarely occur within the oral cavity and infrequently involve the tongue. The majority of lingual neurofibromas arise in patients affected by neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1). Neurofibromas of the tongue unassociated with this disorder are exceedingly uncommon. The clinical and pathologic features of 10 cases of sporadic lingual neurofibromas, unassociated with NF1, were evaluated. The patients included six females and four males ranging in age from 30 to 69 years (mean 59 years; median 63 years). An asymptomatic or slowly enlarging lingual mass was the most common clinical presentation. None of the patients were documented to have NF1. Histologically, the tumors were unencapsulated and situated beneath an intact squamous mucosa. The tumors are comprised of spindle cells with wavy nuclei within a collagenous to myxoid stroma. One tumor was characterized by a plexiform growth pattern. The lesional cells were positive for S-100 protein. Clinical follow up, available for all patients, showed no recurrences and no subsequent development of additional clinical manifestations of NF1. Lingual neurofibromas should be distinguished from other peripheral nerve sheath tumors that can affect this anatomic site. This series of cases confirms that sporadic neurofibromas of the tongue may be rarely encountered in patients having no other features of NF1.

Keywords: Neurofibroma, Tongue, Mouth, Nerve sheath neoplasms, Neurofibromatosis 1, S100 protein

Introduction

Neurofibroma is a benign tumor of peripheral nerve origin composed predominantly of Schwann cells admixed with variable numbers of perineurial-like cells, transitional cells, and fibroblasts. Neurofibromas are well described in the head and neck region but are rarely encountered in the oral cavity [1–6]. The tongue, in particular, is uncommonly affected by neurofibromas. In a series of 66 head and neck cases, lingual examples represented only 4.6% [7]. The majority of neurofibromas of the tongue occur as a manifestation of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) [8–13]. In contrast, sporadic neurofibromas of the tongue, unassociated with NF1, are quite rare, and only a limited number of examples are reported in the literature [1, 14–26]. To the best of our knowledge, sporadic lingual neurofibromas have not been well characterized in a large series of cases. In this study, a comprehensive evaluation of the clinical and pathologic features of ten cases of sporadic neurofibromas of the tongue is presented.

Materials and Methods

Ten cases of neurofibromas involving the tongue were identified from the files of the Departments of Pathology of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group. Hematoxylin and eosin stained slides from all cases and previously performed immunohistochemical studies were reviewed. Clinical data, treatment, and follow up information were obtained from electronic medical records augmented by the surgical pathology reports. All patients lacked clinical manifestations of NF1. No NF1 associated lingual neurofibromas were identified. This clinical investigation was conducted in accordance and compliance with all statutes, directives, and guidelines of an Internal Review Board (authorization #5968) performed under the direction of Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

Results

Clinical Features

The study population was composed of six females and four males who ranged in age from 30 to 69 years, with a mean age at presentation of 58.8 years (median 63 years) (Table 1). Clinical presentation was variable and included an asymptomatic or enlarging mass (n = 4), localized area of tongue pain or irritation (n = 3), tongue swelling (n = 2), and a painful mass (n = 1). The duration of symptoms ranged from 1 to 96 months (mean 29.3 months). Clinical descriptions of the lesions included a nodule or mass, raised area of the tongue, and enlarged or prominent papillae. Clinical records were carefully reviewed, and none of the patients in the study group met any of the diagnostic criteria for NF1 [27].

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic features of ten cases of neurofibroma of the tongue

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Clinical presentation | Symptom duration (months) | Size (cm) | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | M | Painless enlarging mass | 96 | 0.6 | ANED (29) |

| 2 | 30 | F | Tongue swelling | 1.5 | 0.1 | ANED (30) |

| 3 | 76 | M | Painless enlarging mass | 12 | 2.0 | ANED (27) |

| 4 | 66 | F | Painful bump | 1 | 0.2 | ANED (31) |

| 5 | 34 | M | Localized tongue irritation | 2 | 0.2 | ANED (28) |

| 6 | 69 | F | Painless nodule | 12 | 0.5 | ANED (26) |

| 7 | 60 | F | Localized tongue pain and irritation | 12 | 0.1 | ANED (17) |

| 8 | 60 | F | Tongue swelling | 12 | 1.1 | ANED (64) |

| 9 | 68 | F | Localized tongue pain | 60 | 0.5 | ANED (33) |

| 10 | 68 | M | Painless nodule | 84 | 0.5 | ANED (79) |

M male, F female, ANED alive with no evidence of disease

Pathologic Features

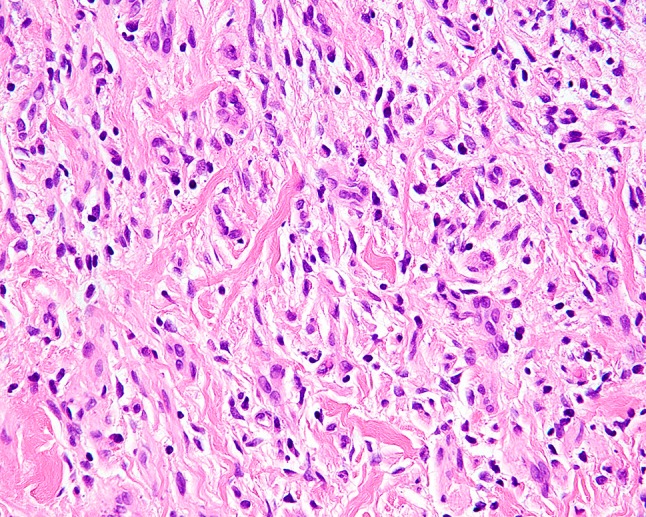

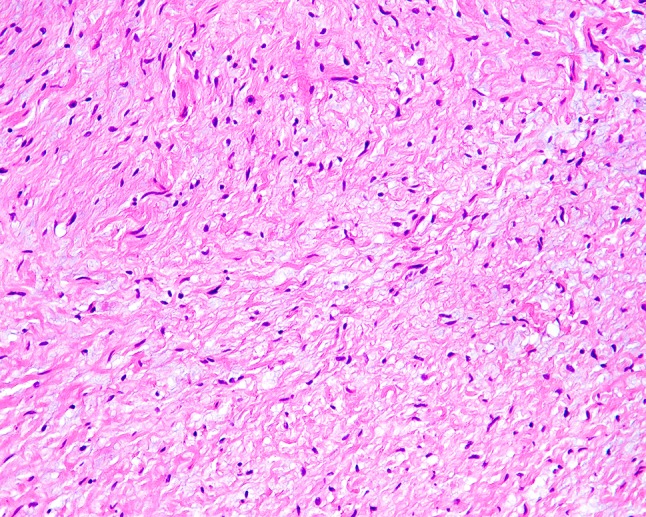

Given the relatively small size of individual lesions, gross descriptions were typically limited to tan-white and nodular. The tumors ranged from 0.1 to 2.0 cm in maximum dimension (mean 0.5 cm). Microscopically, they were ill-defined, unencapsulated, and situated beneath an intact squamous mucosa (Fig. 1). The lesions were comprised of randomly arranged, widely spaced spindle cells with wavy to curved nuclei and scant cytoplasm (Figs. 2 and 3). The spindled cells were separated by strands of collagen and variable amounts of mucoid/myxoid material (Figs. 4 and 5). Occasional small nerve fibers and scattered mast cells were also present. A plexiform growth pattern, characterized by expanded and distorted nerve fascicles replaced by lesional cells, was observed in one case (Fig. 6). The tumors showed no evidence of hypercellularity, pleomorphism, tumor necrosis, or increased mitotic activity. All tumors expressed S-100 protein by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 7).

Fig. 1.

Neurofibroma of the tongue forming an unencapsulated mass beneath an intact squamous mucosa

Fig. 2.

Typical appearance of a lingual neurofibroma. Cytologically bland cells with spindled to ovoid nuclei set in a collagenous stroma are characteristic

Fig. 3.

Spindle cells of neurofibroma frequently display nuclei with a wavy appearance

Fig. 4.

Lesional spindle cells of neurofibroma are separated by collagen fibers

Fig. 5.

Example of a neurofibroma of the tongue with a more prominent myxoid stroma

Fig. 6.

Plexiform neurofibroma of the tongue with multiple adjacent nerve bundles expanded by neurofibromatous tissue

Fig. 7.

Neurofibromas express S-100 protein; however, immunoreactivity is generally observed in only a subset of the lesional cells

Treatment and Follow-Up

All of the tumors were removed through biopsy or local surgical excision without additional treatment. Clinical follow up was available for all patients with a mean duration of 36.4 months (range 17–79 months). None of the patients developed recurrence and all are alive with no evidence of disease. In addition, none of the patients subsequently developed any manifestations of NF1 during the follow up period.

Discussion

The majority of reported lingual neurofibromas arise in the setting of NF1 [8–13]. The frequency of oral involvement in patients with NF1 ranges from to 26 to 37%, and the tongue is among the most common sites affected [9, 11, 28]. In contrast, sporadic neurofibromas of the tongue are rare; to our knowledge only fourteen cases have been previously described in the English literature [1, 14–26]. The clinical and pathologic features of sporadic lingual neurofibromas from the present series and prior published data are summarized in Table 2. The tumor occurs slightly more frequently in women than men, with a female to male ratio of 1.2:1. There is a wide age range at presentation (5–76 years) with a mean of 46.8 years. This differs from neurofibromas of the tongue associated with NF1 which develop predominantly in males with an average age of 20 years [12]. The typical clinical presentation is a painless lingual mass or swelling, often with a history of slow growth. A minority of patients have reported dysphagia, dysphonia, or respiratory difficulty, which correlated with tumors affecting the base of the tongue [15, 19, 23, 24]. Sporadic lingual neurofibromas are benign neoplasms managed adequately by local excision. Radiotherapy has also been proposed as an alternative therapeutic option for selected patients who are not good surgical candidates [25]. No instances of tumor recurrence or malignant transformation occurred in the current series or in prior reports with available follow up data.

Table 2.

Literature summary combined with current cases of tongue neurofibroma unassociated with NF1

| Characteristicsa | Number (n = 24) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 13 |

| Male | 11 |

| Age (in years) | |

| Range | 5–76 |

| Mean | 46.8 |

| Symptom duration (in months) | |

| Range | 0.5–240 |

| Mean | 42.9 |

| Clinical presentation | |

| Painless mass/nodule/swelling | 8 |

| Slowly enlarging mass | 6 |

| Localized pain/irritation | 6 |

| Dysphagia | 4 |

| Dysphonia | 4 |

| Dyspnea | 3 |

| Odynophagia | 1 |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| Range | 0.1–8.0 |

| Mean | 1.6 |

| Patients with follow up (n = 17) | |

| Alive, no evidence of disease | 17 |

| Patients with recurrence | 0 |

| Follow up (months) | |

| Range | 0.75–108 |

| Mean | 33.2 |

aNot stated in all cases

Neurofibromas arising in the tongue, whether sporadic or associated with NF1, exhibit similar histologic features to those occurring in other anatomic sites. The tumor is characterized by an unencapsulated proliferation of spindle cells with elongated, wavy nuclei and scant cytoplasm in a collagenous to myxoid stroma. The tumors lack pleomorphism and show an inconspicuous mitotic rate. The lesional cells may involve and expand multiple nerve fascicles resulting in a plexiform appearance. Plexiform neurofibromas are encountered most commonly in the setting of NF1 and is one diagnostic criterion for this disorder. However, several cases of plexiform neurofibroma involving the tongue are reported in patients exhibiting no other features of NF1 [16, 19, 24–26]. Whether lingual involvement in these cases is truly sporadic or representative of the initial manifestation of NF1 is difficult to determine due to limited reports with clinical follow up. A single, sporadic example of plexiform neurofibroma was identified in this series. The affected patient was a 76 year old male who lacked clinical features of NF1 at presentation and during the 37 months of follow up.

Neurofibromas consistently express S-100 protein and SOX-10, although immunohistochemistry is not usually required for diagnosis. The extent of positivity for these markers can vary depending on the proportion of Schwann cells comprising the lesion. Constituent fibroblastic cells are positive for CD34. EMA expressed in perineurial cells can occasionally be observed at the periphery of the tumor.

While neurofibromas of the tongue are generally recognized without difficulty, the morphologic appearance may overlap with other tumors and tumor-like proliferations of peripheral nerves affecting this anatomic site [29]. Subgemmal neurogenous plaque (SNP) is a normal neural structure associated with taste buds found in the posterolateral region of the tongue [30]. Unlike neurofibromas, SNPs have a distinctive biphasic histologic appearance. They are characterized by wavy elongated spindle cells subjacent to the mucosa and a deeper component of small nerve fascicles and scattered ganglion cells. While the superficial portion of SNPs may resemble a neurofibroma, appreciation of an overall zonal pattern and the deeper area with a neuroma-like appearance facilitates recognition of this normal lingual anatomic structure.

Traumatic neuroma (TN) is a non-neoplastic neural proliferation which occurs in response to nerve injury. Similar to neurofibromas, these lesions are unencapsulated and comprise a proliferation of spindle cells representing the various cellular elements of the peripheral nerve including axons, Schwann cells, and perineurial cells. In contrast with neurofibromas, TNs are relatively more organized with spindle cells arranged in microfascicles of varying sizes. The bundles or fascicles are typically embedded in fibrocollagenous matrix that separates the bundles from each other. This finding differs from the frequently myxoid stroma of neurofibromas. A clinical history of antecedent trauma or injury to the area, if available, also facilitates a diagnosis of TN.

Mucosal neuroma (MN) is characterized by clusters of discrete, enlarged, hypertrophic nerves which are often accompanied by endoneurial mucin. Superficially, they may simulate the appearance of a plexiform neurofibroma. Although enlarged, the microscopic anatomy of the nerves is retained with a generally normal ratio of axons and Schwann cells. This is in contrast to the mixed cellular composition of the neurofibromatous tissue involving nerve fascicles of a plexiform neurofibroma.

Ganglioneuroma is composed of spindled Schwann cells arranged in intersecting bundles admixed with ganglion cells. The ganglion cell component can vary considerably in quantity and distribution, and those lesions with few ganglion cells and a predominance of spindle cells can closely resemble a neurofibroma. This issue is generally resolved by a careful search for ganglion cells which serve to differentiate a ganglioneuroma from neurofibroma.

Palisaded encapsulated neuroma (PEN), which is typified by a lobular or plexiform growth pattern, can be potentially mistaken for neurofibroma. Unlike neurofibromas, PENs are well circumscribed and at least partially encapsulated. These lesions are comparatively more cellular than neurofibromas. Their constituent spindle cells are arranged in compact fascicles and often separated by artefactual clefts. Myxoid stromal change is unusual in PENs and is more typically observed in neurofibromas.

Nerve sheath myxoma (NSM) is characterized by lobules of cells suspended in a prominent myxoid stroma and separated by thin fibrous septae. The lesional cells are often spindled and express S-100 protein, which, along with the myxoid background, may cause confusion with neurofibroma. Morphologically, the cells of NSMs are more heterogeneous with epithelioid, stellate, or ring shaped cells in addition to spindle cells. In contrast, neurofibromas are composed exclusively of spindle shaped cells. This morphologic variability of NSM aids the distinction from neurofibroma.

A spindle cell lipoma (SCL) contains spindled cells within a fatty background. In cases with limited adipose tissue, the spindled cell component may mimic a neurofibroma. SCLs tend to be well circumscribed and are characterized microscopically by a mixture of mature adipocytes, cytologically bland spindle cells, and variable proportions of interspersed bundles of thick collagen fibers. Immunohistochemistry may help the distinction from neurofibroma, as the spindled cells of SCL are positive with CD34 and negative with S-100 protein [31].

Among the various neural tumors which may arise in the tongue, schwannoma is perhaps the lesion most often considered in the differential diagnosis of neurofibroma. In contrast with most schwannomas, neurofibromas lack a thick, well-formed capsule and are more likely to have ill-defined borders. The spindle cells of neurofibroma are uniformly distributed throughout the lesion and do not exhibit the alternating cellular Antoni A and loosely arranged Antoni B areas characteristic of schwannoma. The presence of a palisaded arrangement of nuclei and prominent thick walled or hyalinized vessels are also features favoring a diagnosis of schwannoma.

When entertaining a diagnosis of neurofibroma of the tongue it is important to exclude the possibility of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor. In most circumstances, this distinction is not difficult as the majority of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor exhibit features of a high grade sarcoma. These include a fascicular or storiform growth pattern, prominent cellular atypia, increased mitotic activity, and areas of tumor necrosis. Loss of H3K27me3 expression by immunohistochemistry also supports a diagnosis of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor [32]. However, distinguishing a neurofibroma displaying atypical histologic features from a low-grade peripheral nerve sheath tumor remains a challenge. Recently, the term “atypical neurofibromatous neoplasm of uncertain biologic potential” has been proposed for tumors with at least two of the following histologic features: nuclear atypia, hypercellularity, loss of neurofibroma architecture, and mitotic activity of > 1/50 and < 3/10 high powered fields [33].

In summary, neurofibromas of the tongue are uncommon tumors. The present series emphasizes that neurofibromas can rarely arise in the tongue without association with NF1. In contrast with lingual neurofibromas associated with this disorder, sporadic neurofibromas of the tongue present at an older age and have a slight predilection for females. Clinically, the tumor follows a benign course with no risk of recurrence or malignant transformation. The diagnosis of neurofibroma of the tongue is generally straightforward and based on morphologic features, but distinction from other peripheral nerve sheath tumors that also occur at this site is required.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed are those of the authors solely and do not represent endorsement from Southern California Permanente Medical Group.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest as it relates to this research project.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this retrospective data analysis involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board (IRB #5968), which did not require informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.do Nascimento GJ, de Albuquerque Pires Rocha D, Galvao HC, de Lisboa Lopes Costa A, de Souza LB. A 38-year review of oral schwannomas and neurofibromas in a Brazilian population: clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical study. Clin Oral Investig. 2011;15(3):329–335. doi: 10.1007/s00784-010-0389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos MS, Fontes A, Marocchio LS, Nunes FD, de Sousa SC. Clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features of oral neurofibroma. Acta Odontol Scand. 2012;70(6):577–582. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2011.640286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen SY, Miller AS. Neurofibroma and schwannoma of the oral cavity. A clinical and ultrastructural study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1979;47(6):522–528. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(79)90275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones AV, Franklin CD. An analysis of oral and maxillofacial pathology found in adults over a 30-year period. J Oral Pathol Med. 2006;35(7):392–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salla JT, Johann AC, Garcia BG, Aguiar MC, Mesquita RA. Retrospective analysis of oral peripheral nerve sheath tumors in Brazilians. Braz Oral Res. 2009;23(1):43–48. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242009000100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherrick HM, Eversole LR. Benign neural sheath neoplasm of the oral cavity: report of thirty-seven cases. Oral Surgery Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;32(6):900–909. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(71)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marocchio LS, Oliveira DT, Pereira MC, Soares CT, Fleury RN. Sporadic and multiple neurofibromas in the head and neck region: a retrospective study of 33 years. Clin Oral Invest. 2007;11(2):165–169. doi: 10.1007/s00784-006-0096-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bongiorno MR, Pistone G, Arico M. Manifestations of the tongue in neurofibromatosis type 1. Oral Dis. 2006;12(2):125–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Ambrosio JA, Langlais RP, Young RS. Jaw and skull changes in neurofibromatosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;66(3):391–396. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasi HB, Herr BS, Jr, Sperer AV. Neurofibromatosis of the tongue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965;35:657–665. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196506000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro SD, Abramovitch K, Van Dis ML, Skoczylas LJ, Langlais RP, Jorgenson RJ, et al. Neurofibromatosis: oral and radiographic manifestations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1984;58(4):493–498. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(84)90350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baden E, Jones JR, Khedekar R, Burns WA. Neurofibromatosis of the tongue: a light and electronmicroscopic study with review of the literature from 1849 to 1981. J Oral Med. 1984;39(3):157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayres WW, Delaney AJ, Backer MH. Congenital neurofibromatous macroglossia associated in some cases with von Recklinghausen’s disease; a case report and review of the literature. Cancer. 1952;5(4):721–726. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195207)5:4<721::aid-cncr2820050410>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roy S, Ray KS. A case of solitary neurofibroma of tongue. Indian J Cancer. 1965;2(4):215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roy P, Chakraborty S, Das S, Roy A. Solitary neurofibroma at the base of the tongue: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60(5):497–499. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.164374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sirinoglu H, Bayramicli M. Isolated plexiform neurofibroma of the tongue. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21(3):926–927. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181d7ae5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagahata S, Takagi S, Nishijima K. Neurofibroma of the tongue: a case report. Acta Med Okayama. 1983;37(3):269–272. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lykke E, Noergaard T, Rasmussen ER. Lingual neurofibroma causing dysaesthesia of the tongue. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-010440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guclu E, Tokmak A, Oghan F, Ozturk O, Egeli E. Hemimacroglossia caused by isolated plexiform neurofibroma: a case report. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(1):151–153. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000184511.86579.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahmud SA, Shah N, Chattaraj M, Gayen S. Solitary encapsulated neurofibroma not associated with neurofibromatosis-1 affecting tongue in a 73-year-old female. Case Rep Dent. 2016;2016:3630153. doi: 10.1155/2016/3630153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutta M, Ghatak S. Isolated neurofibroma of the tongue presenting as a papilloangiomatous mass. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011;90(2):58–59. doi: 10.1177/014556131109000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatt AP. Case of the month: neurofibroma of the tongue. J Indian Dent Assoc. 1985;57(10):inside front cover [PubMed]

- 23.Grey P, Kapadia R. Neurofibroma of tongue—case report. J Laryngol Otol. 1972;86(3):275–279. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100075241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharma A, Sengupta P, Das AK. Isolated plexiform neurofibroma of the tongue. J Lab Phys. 2013;5(2):127–129. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.119867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson TC, Buck DA, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Powers CN, Reiter ER. Isolated plexiform neurofibroma: treatment with three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(7):1139–1142. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma SC, Srinivasan S. Isolated plexiform neurofibroma of tongue and oropharynx: a rare manifestation of von Recklinghausen’s disease. J Otolaryngol. 1998;27(2):81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neurofibromatosis. Conference statement. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(5):575–8. [PubMed]

- 28.Jouhilahti EM, Visnapuu V, Soukka T, Aho H, Peltonen S, Happonen RP, et al. Oral soft tissue alterations in patients with neurofibromatosis. Clin Oral Invest. 2012;16(2):551–558. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0519-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright BA, Jackson D. Neural tumors of the oral cavity. A review of the spectrum of benign and malignant oral tumors of the oral cavity and jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980;49(6):509–522. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(80)90075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzaga AKG, Moreira DGL, Sena DAC, Lopes M, de Souza LB, Queiroz LMG. Subgemmal neurogenous plaque of the tongue: a report of three cases. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;21(3):351–355. doi: 10.1007/s10006-017-0629-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau SK, Bishop JA, Thompson LD. Spindle cell lipoma of the tongue: a clinicopathologic study of 8 cases and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9(2):253–259. doi: 10.1007/s12105-014-0574-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cleven AH, Sannaa GA, Briaire-de Bruijn I, Ingram DR, van de Rijn M, Rubin BP, et al. Loss of H3K27 tri-methylation is a diagnostic marker for malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and an indicator for an inferior survival. Mod Pathol. 2016;29(6):582–590. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM, Kim A, Lazar AJ, Quezado MM, et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview. Hum Pathol. 2017;67:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]