Abstract

Lymphangiomas are rare, congenital malformations of the lymphatic system which have a marked predilection for the head and neck. In this region, they most commonly occur on the dorsum of the tongue, followed by the lips, buccal mucosa, soft palate, and floor of the mouth. Lymphangiomas of the tongue are commonly present at birth; however, they may go unnoticed until after eruption of the dentition or even puberty. They may present as a defined mass or as macroglossia with impaired speech, difficulty in mastication, and, in extreme cases, airway obstruction. Clinically, lymphagiomas of the tongue are characterized by clusters of pebbly, vesicle-like nodules. A benign proliferation of lymphatic vessels is identified histologically. A classic case of a lymphangioma of the dorsal tongue is presented.

Keywords: Lymphangioma, Vascular, Soft tissue, Tongue

Clinical Features

A 24 year old female presented to a Malaysian Community Health Engagement Clinic during Pacific Partnership 2019, a joint health operation of the Unites States Navy and Malaysian Armed Forces. Her chief complaint was of a toothache for which she requested an extraction. Intraoral examination revealed partial edentulism and numerous grossly carious teeth including the one causing her pain. The patient’s dorsal tongue was notable for a mass surfaced by pebbly, vesicle-like nodules (Fig. 1). The lesion was partially translucent with areas that appeared red, purple, and yellow. The elevated mass was soft to palpation and non-tender. The patient was aware of the lesion since early childhood with her parents relaying that it had been present for over 20 years. She expressed little concern for the mass and reported only mild discomfort when eating hot and spicy foods. Due to the classic appearance, a working clinical diagnosis of lymphangioma was established.

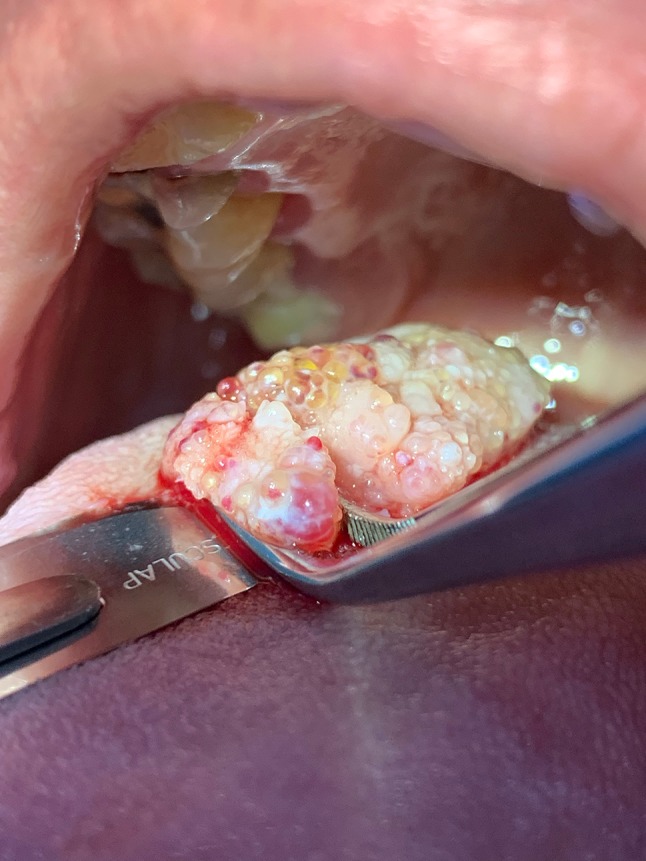

Fig. 1.

Clinical photo of the lymphangioma shows the classic pebbly, vesicle-like appearance of the tumor.

The patient consented to extraction of the tooth cited in the chief complaint, and the procedure was performed without incident. She returned 4 days later for an incisional biopsy of the tongue lesion under local anesthetic (Fig. 2). There were no complications, and the tissue was submitted in formalin for microscopic review.

Fig. 2.

Intraoperative photo shows the tumor’s clear to translucent vesicles mixed with red to purple-hued areas.

Histologic Features

The tissue specimen was received by the Department of Pathology, Tuanku Mizan Armed Forces Hospital, Kuala Lumpur. It measured 1.0 cm in greatest dimension. Histologic review revealed a collection of dilated lymphatic vessels surfaced by normal stratified squamous epithelium (Fig. 3). The lymphatic channels were intimately associated with the overlying epithelium reflecting the translucent and pebbly clinical presentation. The endothelial lining of the channels was thin, and the spaces contained proteinaceous fluid, scant lymphocytes, and red blood cells (Fig. 4). The red blood cells were attributed to the surgical procedure and/or previous trauma. Extension into deep connective tissues and muscle was focally identified. The microscopic diagnosis of lymphangioma was rendered.

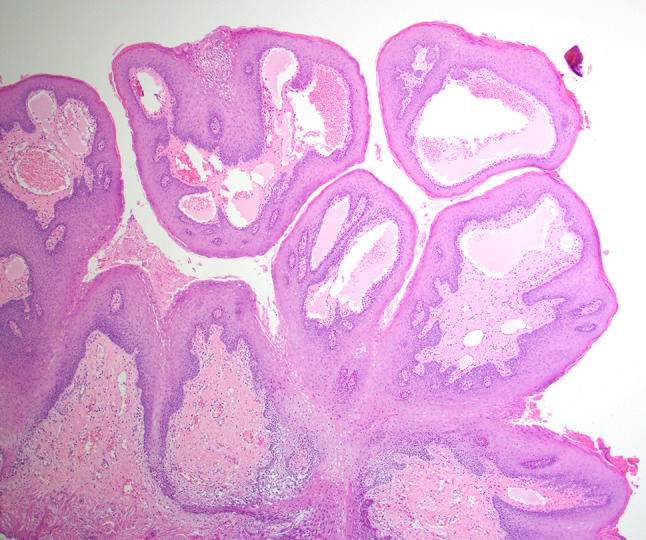

Fig. 3.

Dilated lymphatic vessels intimately associated with the overlying epithelium (low power, hematoxylin and eosin stain).

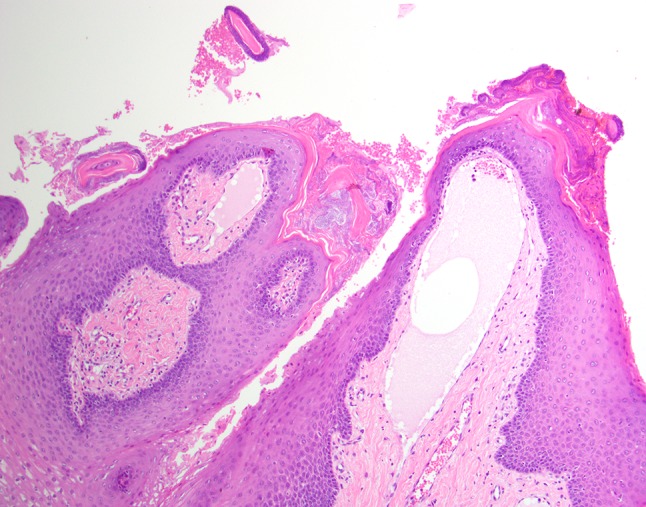

Fig. 4.

The endothelial lined spaces of the lymphangioma are readily identified (high power, hematoxylin and eosin stain).

Clinical Outcome

The patient was informed of the diagnosis and the healing of the biopsy site was uneventful. Regular follow-up intervals were established

Discussion

Lymphangioma is a congenital malformation of lymphatic channels. The proliferation of lymph vessels is hamartomatous and not considered neoplastic. Lymphangiomas are relatively uncommon but show a strong predilection for the head and neck [1, 2]. While skin is the most common site, intraoral lesions are not infrequent and mostly commonly affect the anterior two-thirds of the dorsal tongue. The lips, buccal mucosa, soft palate, and floor of mouth are other sites of occurrence [3]. Most lymphangiomas are present at birth or develop within the first 2 years of life [4, 5].

The patients’ signs and symptoms are dependent on the size and precise intraoral location. If small, lymphangiomas of the tongue may go unnoticed. Larger lesions may compromise speech and/or eating. Bleeding may occur with minor trauma associated with normal oral functions such as eating, speaking, and hygiene, and some patients report a burning sensation associated with their lesion [4]. In extreme cases, lymphagiomas can be life threatening by causing airway obstruction or if secondarily infected [4].

Most lymphangiomas of the tongue have a classic clinical appearance. Lesions of this location are usually superficial, or have a superficial component, that corresponds to the characteristic pebbly, translucent, and yellow vesicles said to resemble frog eggs [4]. Additionally, lesions frequently have a red or purple hue that results from hemorrhage into the lymphatic channels.

Histologically, lymphagiomas consist of lymphatic channels lined by endothelial cells. The size and shape of the channels are variable and lesions may be classified accordingly. Cavernous lymphangiomas comprise primarily dilated vessels, capillary lymphangiomas have capillary-sized vessels, and large, cyst-like spaces are characteristic of cystic lymphangiomas [2]. Lesions tend to be a mixture of sizes, however, and these distinctions may not be contributory to the management of the case. The endothelial cells of lymphangiomas are reactive for CD31, CD34, and D2-40 [6, 7].

The clinical differential diagnosis for a lymphangioma may include any “bump of the tongue.” As in this case, a dorsal location may suggest entities including, but not limited to, granular cell tumor, lingual thyroid, and mesenchymal tumors. Of the mesenchymal linage, vascular lesions, including hemangiomas, vascular malformations, and arteriovenous malformations are the main consideration. Additionally, pyogenic granuloma, a reactive lesion, part of the differential diagnosis. Despite the classic clinical presentation of lymphangioma of the dorsal tongue, histopathologic review will assist in providing a precise diagnosis.

When considering the differential diagnosis, hemangiomas, particularly infantile hemangiomas, share a similar clinical profile and natural history with lymphangiomas [8]. They are frequently congenital or develop soon after birth and also favor the head and neck. Hemangiomas have the same sites of predilection and are considered common [8]. Head and neck hemangiomas of the mucosa or skin, when first are noticed, may appear as flat red macules or raised masses. This is frequently followed by a proliferative stage in which the lesion grows rapidly. Over the course of years infantile hemangiomas involute. As stated previously, tongue lymphangiomas may develop soon after birth but regression is not a feature. Characteristically, tongue lymphangiomas demonstrate a classic frog egg clinical appearance, this finding is absent in hemangiomas.

Histologically, hemangiomas display multiple vessels lined by endothelial cells. Similarly to lymphangiomas, the vessels may be of varying sizes. Infantile hemangiomas may show marked endothelial proliferation, however. The intimate relationship with the overlying epithelium that is characteristic of lymphangiomas is not generally seen in hemangiomas. Additionally, infantile hemangiomas are overwhelmingly reactive (over 95%) for GLUT-1 while lymphaniomas are non-reactive [8, 9].

Of the vascular lesions, venous malformation is the next diagnostic consideration. These lesions tend to be present at birth (although they may not be noticed) and persist like lymphangiomas. Clinically, venous malformations may be red or blue. Lesions may be nodular or have blebs (a blister-like appearance) that is similar to a lymphangioma. Venous malformations are typically compressible and may demonstrate a thrill or bruit whereas lymphangiomas will not [8]. Histologically, venous malformations are composed of aberrant vessels often times dilated, filled with red blood cells. Endothelial cell proliferation is generally not a feature of vascular malformations.

A less common and perhaps a remote consideration is arteriovenous malformation, particularly in this tongue. This lesion is of concerning clinical consequence due to their high flow. Additionally, they usually do not present until adulthood. A working diagnosis is often established by clinical presentation then verified with advanced imagining. Due to concerns for excessive bleeding biopsy is not performed. Tissue may be submitted after surgical intervention and may show numerous vessels of varying sizes, thrombosis, calcification and emblolizing material [10]. The clinically worrisome presentation of this entity generally excludes lymphangioma.

Finally, pyogenic granuloma may be part of the differential diagnosis. This lesion is not a neoplasm, it is a localized reaction to trauma or irritation. Common in children and young adults, intraorally these tumor-like growths favor the gingiva, however, are frequently found on the tongue. Clinically, pyogenic granulomas may present as a sessile or pedunculated red to pink mass, frequently ulcerated. Histologically, they may resemble granulation tissue with a vague lobular architecture of the vessels. Pyogenic granulomas may be very inflamed, demonstrating both acute and chronic inflammation with or without ulceration.

Lymphangiomas of the tongue are generally not a diagnostic dilemma. The histologic features are characteristic and the clinical appearance often classic. A detailed review of the vascular lesions in the differential diagnosis is beyond the scope of this paper, however, differentiating a lymphangioma from these entities is assisted by identifying the contents of the vessels. The channels of lymphagiomas are filled with proteinaceous fluid and scant lymphocytes whereas the other vascular lesions contain red blood cells. It is important to remember that surgical trauma or even normal functional trauma may result in red blood cells within the vessels of a lymphangioma, so their presence does not exclude this diagnosis. Additionally, immunohistochemical markers CD31 and CD34 are expressed in the endothelial cells of all vascular lesions, but only lymphatic endothelial cells are reactive to D2-40 [6, 7]. While this marker may be helpful to differentiate the type of vessels, it should be stressed that all the entities considered in the differential diagnosis are usually best interpreted with hematoxylin and eosin stained sections.

Treatment for lymphangiomas of the tongue is usually surgical excision; however, complete removal may be complicated by the size and infiltrative nature of the lesion. Several treatment modalities have also been utilized including injection of sclerosing agents, radiofrequency ablation, electrocoagulation, cryotherapy, embolization, steroid administration, radiation, and laser surgery [11, 12].

Post-operative complications are reported in as many as 12–33% of cases and recurrence is seen in 15–53% of cases [13]. Common complications associated with surgical resection of lingual lymphangioma include hemorrhage that can be difficult to control due to the vascular nature of the lesions. Incomplete resection of the lesion is another complication frequently encountered due to the infiltrative properties of lymphangiomas which contributes to the high rate of recurrence. Due to the high rates of complication and recurrence, surgery is typically driven by symptomology and functionality. After diagnosis, lesions that are asymptomatic and do not impair function can be left with routine follow up and scheduled monitoring.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their mutual gratitude for the opportunity to work together as a result of the combined efforts of the United States Navy and the Malaysian Armed Forces. Lasting professional and personal friendships were forged among the contributing teams.

Funding

This study has no funding.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author and are not to be construed as official or representing the views of the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours. 4th Edition. International Agency for Research on Cancer Lyon, 2017.

- 2.Sunil S, Gopakumar D, Sreenivasan BS. Oral lymphangioma: case reports and review of literature. Contemp Clin Dent. 2012;3(1):116–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.94561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.V U, Sivasankari T, Jeelani S, Asokan GS, Parthiban J. Lymphangioma of the tongue: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(9):ZD12–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/9890.4792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goswami M, Singh S, Gokkulakrishnan S, Singh A. Lymphangioma of the tongue. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2011;2(1):86–8. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.85862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayhan KB, Keskin Y, Kesimli MC, Ulusan M, Unur M. Lyphangioma of the tongue: report of four cases with dental aspects. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2014;24(3):172–6. doi: 10.5606/kbbihtisas.2014.00236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaita T, Onodera K, Xu H, Ooya K. Histomorphometrical study in cavernous lymphangioma of the tongue. Oral Dis. 2007;13(1):99–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2006.01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolay SK, Parwani R, Wanjari S, Singhal P. Oral lymphangiomas: clinical and histopathological realations: an immunohistochemically analyzed case series of varied clinical presentations. J Oral Maxillofacial Pathol. 2018;22(Suppl 1):S108–S111. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_157_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoff SR, Rastatter JC, Richter GT. Head and neck vascular lesions. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2015;48(1):29–45. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Vugt LJ, van der Vleuten CJM, Flucke U, Blokx WAM. The utility of GLUT1 as a diagnostic marker in cutaneous vascular anomalies: a review of the literature and recommendations for daily practice. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213(6):591–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richter GT, Suen J, North PE, James CA, Waner M, Buckmiller LM. Arterivenous malformations of the tongue: a spectrum of disease. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(2):328–35. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000249954.77551.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fliegelman LJ, Friedland D, Brandwein M, Rothchild M. Lymphatic malformation: predictive factors for recurrence. Otolaryngol head Neck Surg. 2000;123(6):760–10. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leboulanger N, Roger G, Caze A, Enjolares O, Denoyelle F, Garabedian EN. Utility of radiofrequency ablation for haemorrhagic lingual lymphangioma. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;72:953–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colbert SD, Seager L, HaIDer F, Evans BT, Anand R, Brennan PA. Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck-current concepts in management. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]