Abstract

Clear cell acanthoma (CCA), also known as pale cell acanthoma, represents a rare benign epidermal tumor with strong predilection for the lower extremities of middle-aged individuals and no frank gender preference. The etiology of CCA is poorly understood, although a localized psoriasiform reaction is favored. Herein, we report on the clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features, and HPV status of an apparent example of oral CCA. A 58-year-old female presented with a well-circumscribed, asymptomatic, exophytic, sessile and erythematous nodule of the right hard palate, measuring 0.7 cm in greatest dimension. Microscopically, the lesion featured parakeratosis and acanthosis with neutrophilic microabscesses and broad elongated rete pegs. In areas, spinous epithelial cells exhibited pale or clear cytoplasm without nuclear pleomorphism, mitoses or cytologic atypia. The supporting connective tissue revealed mild chronic inflammation with few scattered neutrophils and numerous capillary vessels. PAS histochemical stain with and without diastase disclosed the presence of cytoplasmic glycogen in the pale cells. The majority of glycogen-rich epithelial cells stained strongly for EMA and were negative for D2-40. Ki-67 immunostaining was confined only to the basal cell layer of the epithelium. A diagnosis of CCA was rendered. The lesion was negative for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, as assessed by HPV-DNA PCR using the MY09/11 primers for the L1 conserved region, thus HPV infection does not appear to contribute to the pathogenesis of oral CCA. In conclusion, we report an intraoral example of CCA in order to raise awareness about this entity.

Keywords: Clear cell acanthoma, Pale cell acanthoma, Glycogen-rich acanthoma, Oral cavity, Clear cell acanthosis, EMA, HPV–PCR

Introduction

Originally described by Degos et al. [1] in 1962, clear cell acanthoma (CCA), alternatively known as pale cell acanthoma, represents an uncommon benign epidermal tumor with strong predilection for the lower extremities, followed by the skin of the trunk and torso, and the scrotum [1–3]. CCA affects primarily middle-aged and elderly individuals between 50 and 70 years of age, with no frank gender preference [2, 4, 5]. Rare onset in younger patients has been reported [6].

Clinically, CCA manifests as a well-circumscribed, firm, elevated, dome-shaped papule or nodule with a brown or erythematous surface, measuring between 0.5 and 2.0 cm [2, 6, 7]. The red overlying surface of CCA can often appear crusted, exudative, and hemorrhagic upon minor trauma [2]. A scaly collarette and vascular puncta are usually seen [2, 4, 6, 8, 9]. By dermoscopy, CCA shows a characteristic “string of pearls” distribution of the dotted/globular vessels underlying the surface epithelium [10]. The clinical features of CCA are, apparently, non-distinctive and can mimic other reactive or neoplastic lesions especially lobular capillary hemangioma (so-called “pyogenic granuloma”) [6, 9, 11]. The progression of CCA is slow and inconspicuous, consistent with the benign nature of this lesion; some cases increased in size over the course of 2–10 years [3]. Although CCAs present typically as solitary nodules, multiple lesions have been infrequently documented in association with Cowden Syndrome [12], varicose veins and ichthyosis [6].

As indicated by its nomenclature, the histopathologic hallmark of CCA is the presence of a well-demarcated psoriasiform acanthotic lesion with abundant, large, pale (clear) epithelial cells, especially in the spinous cell layer [1–4, 12, 13]. These pale cells show high intracellular glycogen content, secondary to decreased or absent respiratory enzymes such as phosphorylase, cytochrome oxidase, and succinic dehydrogenase [2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 14]. Neutrophilic exocytosis, parakeratotic microabscesses, and vasodilatation are usually seen [2, 7, 8, 12, 13, 15, 16]. The pale cells of CCA stain positively with PAS and are labile to digestion with diastase [2, 15]. By immunohistochemistry, CCA consistently stains strongly for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) [15, 16] and involucrin [6, 17], rarely for D2-40 (podoplanin) [18], and is negative for carcinoembryonic antigen [6].

The etiology of CCA is poorly understood [19, 20]. Despite the initial hypothesis supporting a benign neoplastic process [1], a substantial body of clinical and immunohistochemical evidence favors a localized psoriasiform reaction [2, 15, 21]. CCA of the skin is frequently seen in association with various inflammatory conditions including psoriasis [22], ichthyosis [23] seborrheic keratosis [24] and stasis, atopic or bacterial dermatitis [15, 21]. Furthermore, CCA shows similar immunohistochemical features to psoriasis, lichen planus, and discoid lupus erythematous [15, 25]. The potential role of human papillomavirus (HPV) has not been thoroughly investigated in CCA.

To the best of our knowledge, well-documented intraoral CCAs in the English literature have not been reported according to an extensive Pubmed search using the keywords “oral clear/pale cell acanthoma”, “clear cell acanthosis”, “Degos acanthoma”, “glycogen-rich acanthoma”, save for an example affecting the vermillion mucosa of the lower lip [3]. In addition, a few cases of glycogenic acanthosis of the oral mucosa have been reported without further characterization [26]. Herein, we present the clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical characteristics, and HPV status of CCA involving the hard palate of a 58-year-old woman seen recently in our laboratory.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemistry

Four µm FFPE tissue sections were stained with antibodies against Epithelial Membrane Antigen for 16 min [EMA, clone E29; mouse monoclonal, prediluted from Ventana, Tucson, AZ—Antigen retrieval with Cell Condition 1 (CC1) for 36 min] and podoplanin for 32 min (clone D2-40; mouse monoclonal, prediluted from Agilent Dako, Santa Clara, CA—Antigen retrieval with CC1 for 64 min) following the manufacturers’ instructions along with appropriate positive controls. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using the ultraView Universal DAB Detection Kit on the BenchMark ULTRA fully automated immunostaining platform (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ). Immunostaining for the proliferation marker Ki-67 was performed manually using a rabbit monoclonal antibody (clone SP6; 1:400 dilution, overnight incubation, from Thermo Fischer Scientific, Rockford, IL), following a 35-min antigen retrieval step with Reveal Decloaker (BioCare Medical, Pacheco, CA).

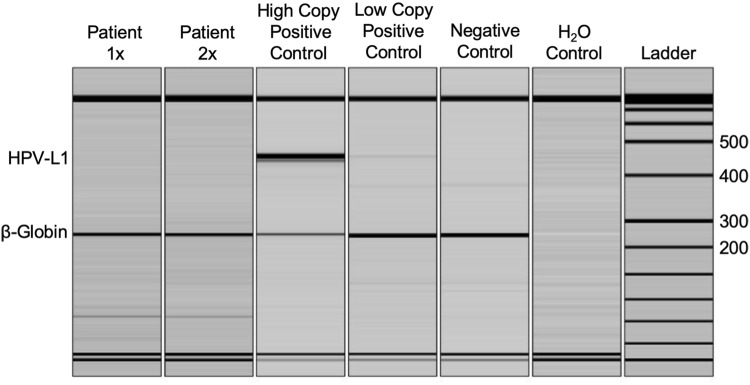

HPV DNA Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

PCR detection of HPV DNA was performed in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certified molecular diagnostics laboratory (University of Minnesota Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory). Routine sensitivity testing is performed on a quarterly basis and consistently demonstrates a limit of detection of 250 copies of the HPV viral genome. DNA was extracted from the formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue block using the DNeasy tissue kit according to manufacturer’s protocols (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Amplification of HPV DNA was performed using the MY09/11 primers for the L1 conserved region (MY11: 5′GCM CAG GGW CAT AAY AAT GG-3′; MY09: 5′ CGT CCM ARR GGA WAC TGA TC-3′; where Y = C,T; R = A,G; M = A,C; W = A,T at the degenerate nucleotide sites) in a duplexed PCR reaction with primers for human beta-globin as an internal control (Fwd: 5′ GAA GAG CCA AGG ACA GGT AC-3′; Rev: 5′ CAA CTT CAT CCA CGT TCA CC-3′). PCR amplification was carried out for 35 cycles using Amplitaq polymerase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) under the following conditions: denaturation 94 °C 30′, annealing 53 °C 30′, and extension 72 °C 30′. PCR reaction products were analyzed on a QIAxcel multicapillary gel electrophoresis system (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Expected product sizes are HPV L1 region: 450 bp (approximate), and beta-globin: 268 bp. The positive control consists of HPV type 16 DNA (WHO International Standard) mixed with HPV-negative human DNA to a dilution representative of 2 copies of the HPV genome/diploid cell. Positive samples are then restriction digested using PstI, RsaI, and HaeIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) in separate reactions, and RFLP products are separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining for genotype interpretation by a pathologist, as previously reported [27–29].

Case Report

A 58-year-old woman presented with a well-circumscribed, asymptomatic, exophytic, sessile and erythematous nodule of the right hard palate, measuring 0.7 cm in greatest dimension (Fig. 1). The surface of the lesion showed delicate red and white striations. The clinical differential diagnosis included squamous papilloma, verruca vulgaris and lobular capillary hemangioma (pyogenic granuloma). An excisional biopsy of the lesion was performed.

Fig. 1.

Clinical characteristics of oral clear cell acanthoma (CCA) presenting as a round, well-demarcated, sessile, erythematous nodule of the right hard palate

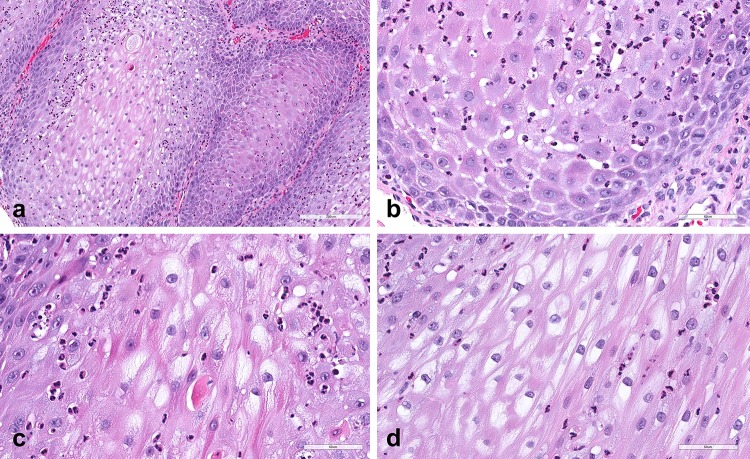

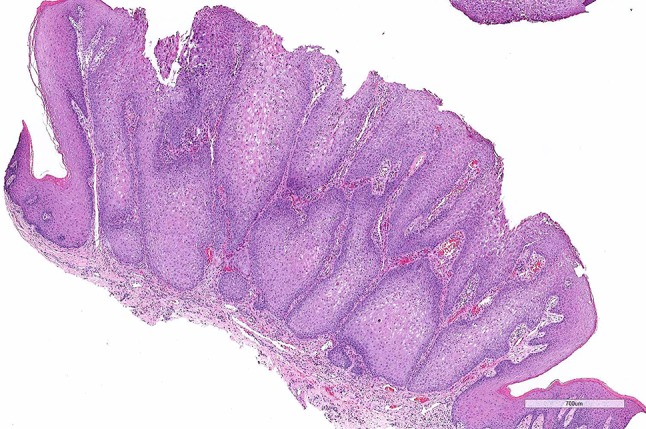

Histopathologic examination revealed an outgrowing epithelial lesion showing clear demarcation from the adjacent non-lesional stratified squamous mucosal epithelium (Fig. 2), which featured pronounced parakeratosis and acanthosis with broad, thickened and elongated rete pegs (Figs. 2, 3a). Neutrophilic microabscesses were present throughput the thickness of the lesion resembling a psoriasiform pattern (Fig. 3b, c). Prominent spongiosis was also seen (Fig. 3b). The majority of epithelial cells of the spinous cell layer exhibited pale or clear cytoplasm without nuclear pleomorphism, mitoses or cytologic atypia (Fig. 3c, d). Scarce mitotic figures were seen at the basal cell layer (Fig. 3b). The supporting connective tissue revealed numerous small capillary vessels and mild chronic inflammation with a few scattered neutrophils.

Fig. 2.

Histopathologic features of CCA; low-power photomicrograph revealing an exophytic epithelial lesion showing parakeratosis and pronounced acanthosis with broad, thickened and elongated rete pegs. Note the clear demarcation from the adjacent non-lesional mucosal epithelium and the numerous capillaries in the connective tissue

Fig. 3.

a Medium-power photomicrograph of the lesion showing prominent acanthosis and bulky rete pegs. b High-power photomicrograph displaying psoriasiform-like neutrophilic exocytosis present throughput the thickness of the lesion. Spongiosis was seen at the cells of the spinous cell layer, as well as scarce mitoses at the basal cells. c, d The majority of epithelial cells of the spinous cell layer exhibited glycogen-rich, pale or clear cytoplasm. Note the neutrophilic microabscesses that are scattered between or around the clear cells

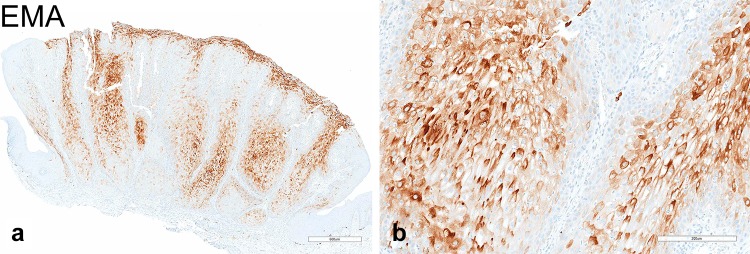

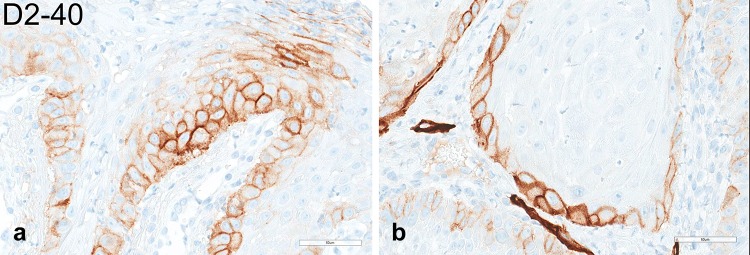

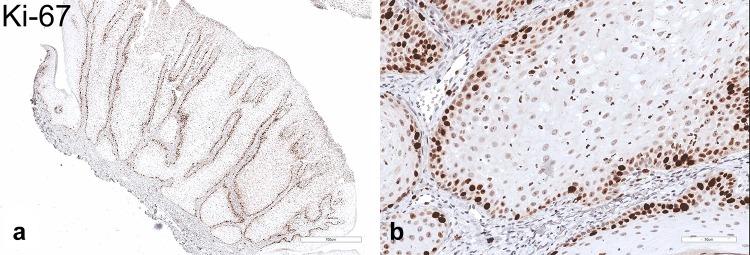

The pale/clear cell population stained strongly with Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) (Fig. 4a, b) and was sensitive to diastase treatment (Fig. 4c, d), supporting the presence of abundant cytoplasmic glycogen. On the basis of the clinicopathologic and histochemical findings, the diagnosis of CCA was rendered. By immunohistochemistry, the majority of glycogen-rich clear cells featured strong and diffuse, cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for EMA (Fig. 5a, b) but were negative for D2-40, which selectively decorated cells of the basal and suprabasal layers only (Fig. 6a, b). Expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 was low and confined to the basal cells (Fig. 7a, b). The lesion was negative for the presence of transcriptionally active HPV infection (Fig. 8).

Fig. 4.

a, b Low- and high-magnification photomicrographs of PAS staining. c, d PAS staining following diastase digestion. The pale/clear cell population stained strongly PAS but was labile to diastase treatment, confirming the presence of cytoplasmic glycogen

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical properties of CCA; a, b EMA immunostaining at low- and high-power magnification, respectively. The cytoplasm of most glycogen-rich clear cells stained strongly and diffusely against EMA. Notably, basal cells at the periphery and the normal adjacent epithelium are EMA-negative

Fig. 6.

a, b High-power photomicrographs of D2-40 immunostaining. Clear cells were negative for D2-40, which selectively decorated cells of the basal and suprabasal layer only

Fig. 7.

a, b Low- and high-power photomicrographs of the proliferation marker Ki-67. As anticipated, Ki-67 nuclear staining was confined to the basal epithelial cells

Fig. 8.

Oral CCA is negative for L1 HPV DNA. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed for HPV-L1 (450 bp) and for human β-globin (250 bp) as an internal control for DNA quality. DNA extract from the patient’s lesion was tested at two different mass inputs. High copy and low copy HPV controls illustrated the dynamic range and lower limit of detection. Negative human DNA control and no template control (H2O) showed no HPV contamination

Discussion

CCA is a rare benign epithelial tumor typically affecting the skin of lower extremities, trunk, torso, and scrotum of patients in their 5th or 6th decade of life [1–3]. In women, the areola presents as a frequent location as well [7, 13]. Following the initial description of this lesion in 1962 [1], Degos and Civatte [4] reported of a cohort of 104 cases of CCA [1, 4]. Involvement of the head and neck region is rare with only two out of 104 lesions (0.02%) located at the skin of the lips [4]. In the study by Weitzner et al. [3]. reviewing 143 previously reported CCAs, 122 (85.2%) affected the lower extremities, whereas 7 (5%) the head and neck skin; two on the lip and one each on the cheek, forehead, retroauricular area, ear and nose [3, 30]. Intraoral CCA appears, thus, uncommon to say the least, with only one previously recorded example affecting the vermilion mucosa of the lower-lip which clinically resembled leukoplakia [3]. In addition, Summerlin and Tomich [26] reported on 7 oral mucosal lesions exhibiting optically clear, glycogen-rich cytoplasm and classified them as “glycogenic acanthosis” or “glycogen-rich acanthoma” based upon the size and possible association with tobacco and alcohol use. Notably, one of the lesions was in close proximity to an area of epithelial dysplasia [26]. Further information regarding the epidemiologic and clinicopathologic properties of the lesions was not provided.

The clinicopathologic characteristics of CCA are well-documented; the lesion is exophytic, well-demarcated and rounded, and features psoriasiform acanthosis with glycogen-rich clear- or pale-staining epithelial cells. Dilated blood vessels can be seen in the superficial dermis, explaining the erythematous color [2]. CCA can be categorized depending on the number of lesions as solitary or multiple. Other clinical variations include giant, eruptive, polypoid, pigmented, atypical, and cystic [2, 5]. In cases of cutaneous CCA, the differential diagnosis is broad and encompasses reactive and neoplastic processes such as actinic keratosis, epidermal nevi, wart, lymphangioma circumscriptum, eccrine poroma, pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibroma, basal or squamous cell carcinoma, and metastatic cancer [2, 3, 8, 13, 16, 18].

Microscopically, CCA should be differentiated, according to the literature, from clear cell hidradenoma or syringoma, trichilemmoma, hidroacanthoma simplex, large cell acanthoma, and eccrine carcinoma [2, 3, 7, 8, 14, 18]. Notably, CCA should not be confused with clear cell acanthosis, a reaction pattern of the epidermis that can occur within other lesions such as seborrheic keratosis and verruca vulgaris, or even normal skin [31, 32].

Although the diagnosis of CCA is rendered on the basis of the histopathologic features, ancillary histochemical and immunohistochemical markers may further support such a diagnosis. Staining with PAS prior and after digestion with diastase confirms the abundance of glycogen in the cytoplasm of keratinocytes [2, 15], also supported by electron microscopy studies [33]. In addition, the phosphorylase enzyme necessary for degradation of glycogen is found to be absent in the CCA cells [2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 14]. CCA consistently stains strongly for EMA [15, 16, 25], cytokeratin AE1/AE3 [15, 25] and involucrin [6, 17, 25]. Strong and diffuse D2-40 immunoreactivity was reported in one case [18]. In contrast to trichilemmoma, CCA fails to show any evidence of outer follicular sheath differentiation, as confirmed by negative staining for MNF116 and NGFR/p75 [15]. In the current intraoral CCA, the largest portion of clear cells stained strongly for EMA, whereas the adjacent non-lesional epithelium was negative. D2-40 was, overall, negative save for some cells of the basal and suprabasal layer.

The etiology of CCA is unknown. CCA was originally considered to be a benign neoplasm [1, 4] originating from the epidermis, hair follicles, or the acrosyringium/sweat gland [2]. However, more recent clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical findings strongly indicate that CCA is a reactive and localized, psoriasiform dermatitis [2, 21, 25]. Interestingly, CCA shares similar immunohistochemical characteristics of cytokeratin expression with psoriasis, lichen planus and discoid lupus erythematosus [15, 25]. Furthermore, cases of CCA are frequently reported in association with active plaque-type psoriasis [22], ichthyosis [23] seborrheic keratosis [24] and stasis, atopic or bacterial dermatitis [15, 21]. Potenziani et al. [12] reported multiple CCAs in a 63-year-old male patient with Cowden syndrome. The possibility of trauma contributing to the development of CCA cannot be excluded, especially in the present lesion affecting the palate. Finally, the potential implication of HPV in CCA of the skin has rarely been addressed, with negative results [2]. HPV-DNA PCR failed to demonstrate transcriptionally active HPV infection in the current intraoral CCA, further indicating that the pathogenesis of CCA is not viral-related.

The prognosis of cutaneous CCA is excellent with rare examples of recurrences reported following surgical excision [34, 35]. Treatment options depend on size, location and number of lesions. The treatment of choice is complete surgical removal. Malignant variants of CCA have been infrequently reported and are characterized by pronounced cytologic atypia and high cellular proliferation with more than 50% of cells detected as Ki-67 positive [14]. In our case, atypia, pleomorphism and mitotic figures were absent, and Ki-67 immunopositivity was limited only to the basal epithelial layer. No recurrence has been reported after a 6-month follow-up period.

In conclusion, we are presenting the clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features, and HPV status of an ostensible example of CCA manifesting in the oral cavity. In our opinion, in regard to intraoral CCA, the non-pathognomonic clinical appearance of the lesion and the overlapping histopathologic characteristics (i.e. psoriasiform exocytosis) with other reactive pathoses may lead to failure to diagnose the entity.

Acknowledgements

The authors are indebted to Mr. Brian Dunnette (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN) for his assistance with preparation of the illustrations.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Degos R, Delort J, Civatte J, Poiares Baptista A. Epidermal tumor with an unusual appearance: clear cell acanthoma. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1962;89:361–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tempark T, Shwayder T. Clear cell acanthoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:831–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weitzner S. Clear-cell acanthoma of vermilion mucosa of lower lip. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1974;37:911–914. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(74)90443-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Degos R, Civatte J. Clear-cell acanthoma. Experience of 8 years. Br J Dermatol. 1970;83:248–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1970.tb15695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morrison LK, Duffey M, Janik M, Shamma HN. Clear cell acanthoma: a rare clinical diagnosis prior to biopsy. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1008–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patterson JW, Weedon D. Weedon’s skin pathology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuo KL, Lo CS, Lee LY, Yang CH, Kuo TT. Clear cell acanthoma (CCA)-like lesions of the nipple/areola: a clinicopathological study of 12 cases supporting a nonneoplastic eczematous disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veiga RR, Barros RS, Santos JE, Abreu Junior JM, MeJ Bittencourt, Miranda MF. Clear cell acanthoma of the areola and nipple: clinical, histopathological, and immunohistochemical features of two Brazilian cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:84–89. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962013000100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patterson JW, Wick MR. Nonmelanocytic tumors of the skin. Washington: American registry of pathology in collaboration with the Armed forces Institute of pathology; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyake T, Minagawa A, Koga H, Fukuzawa M, Okuyama R. Histopathological correlation to the dermoscopic feature of “string of pearls” in clear cell acanthoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:498–499. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2014.2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dudley K, Barr WG, Armin A, Massa MC. Nevus comedonicus in association with widespread, well-differentiated follicular tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:1123–1127. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(86)70278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Potenziani S, Applebaum D, Krishnan B, Gutiérrez C, Diwan AH. Multiple clear cell acanthomas and a sebaceous lymphadenoma presenting in a patient with Cowden syndrome—a case report. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:79–82. doi: 10.1111/cup.12823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borda LJ, Mervis JS, Romanelli P, Lev-Tov H. Clear Cell Acanthoma on the Areola. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. [PubMed]

- 14.Lin CY, Lee LY, Kuo TT. Malignant clear cell acanthoma: report of a rare case of clear cell acanthoma-like tumor with malignant features. Am J Dermatopathol. 2016;38:553–556. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zedek DC, Langel DJ, White WL. Clear-cell acanthoma versus acanthosis: a psoriasiform reaction pattern lacking tricholemmal differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:378–384. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31806f46f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shalin SC, Rinaldi C, Horn TD. Clear cell acanthoma with changes of eccrine syringofibroadenoma: reactive change or clue to etiology? J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:1021–1026. doi: 10.1111/cup.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hashimoto T, Inamoto N, Nakamura K, Harada R. Involucrin expression in skin appendage tumours. Br J Dermatol. 1987;117:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1987.tb04139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasuga N, Kunisada M, Tanaka M, Nishigori C. Case of podoplanin-positive clear cell acanthoma. J Dermatol. 2018;45:233–235. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy R, Kesseler ME, Slater DN. Giant clear cell acanthoma. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:1114–1115. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamasaki K, Hatamochi A, Shinkai H, Manabe T. Clear cell acanthoma developing in epidermal nevus. J Dermatol. 1997;24:601–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SY, Jung JY, Na JI, Byun HJ, Cho KH. A case of polypoid clear cell acanthoma on the nipple. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:337–340. doi: 10.5021/ad.2010.22.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finch TM, Tan CY. Clear cell acanthoma developing on a psoriatic plaque: further evidence of an inflammatory aetiology? Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:842–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landry M, Winkelmann RK. Multiple clear-cell acanthoma and ichthyosis. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:371–383. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1972.01620060013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams RE, Lever R, Seywright M. Multiple clear cell acanthomas–treatment by cryotherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:300–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohnishi T, Watanabe S. Immunohistochemical characterization of keratin expression in clear cell acanthoma. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Summerlin D-J, Tomich C. Abstracts of papers presented at the forty-seventh annual meeting of the American Academy of Oral Pathology. Oral Pathol Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1993;76:13. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Argyris PP, Nelson AC, Papanakou S, Merkourea S, Tosios KI, Koutlas IG. Localized juvenile spongiotic gingival hyperplasia featuring unusual p16INK4A labeling and negative human papillomavirus status by polymerase chain reaction. J Oral Pathol Med. 2015;44:37–44. doi: 10.1111/jop.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Argyris PP, Kademani D, Pambuccian SE, Nguyen R, Tosios KI, Koutlas IG. Comparison between p16 INK4A immunohistochemistry and human papillomavirus polymerase chain reaction assay in oral papillary squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;71:1676–1682. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Argyris PP, Nelson AC, Koutlas IG. Keratinizing odontogenic cyst with verrucous pattern featuring negative human papillomavirus status by polymerase chain reaction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119:e233–e240. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brownstein MH, Fernando S, Shapiro L. Clear cell acanthoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 37 new cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1973;59:306–311. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/59.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fukushiro S, Takei Y, Ackerman AB. Pale-cell acanthosis. A distinctive histologic pattern of epidermal epithelium. Am J Dermatopathol. 1985;7:515–527. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198512000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ko CJ, Subtil A. Clear (pale) cell acanthosis as an incidental finding. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:573–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Desmons F, Breuillard F, Thomas P, Leonardelli J, Hildebrand HF. Multiple clear-cell acanthoma (Degos): histochemical and ultrastructural study of two cases. Int J Dermatol. 1977;16:203–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1977.tb01853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashimoto T, Inamoto N, Nakamura K. Two cases of clear cell acanthoma: an immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1988;15:27–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1988.tb00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim CY, Kim NG, Oh CW. Multiple reddish weeping nodules on the genital area of a girl Giant clear cell acanthoma (CCA) Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e67–e69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]