Abstract

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD) is a benign, self-limiting histiocytosis of unknown etiology. The classic form of the condition includes a painless cervical lymphaenopathy accompanied by fever, weight loss and an elevated ESR. Extra nodal RDD (ENRDD) is most frequent in the head and neck. Thirty-eight cases of ENRDD have been described. Seven cases of ENRDD were identified in our pathology biopsy services. The demographic and clinical information was tabulated logically on the basis of age, gender, location and presence or absence of symptoms, treatment and follow-up. Radiographic and histopathological features were also examined. The findings in these cases were correlated with those available from the previously reported cases. Six cases affected women and one case was diagnosed in a male. The age ranged from 22–55 years. Three cases presented as a nasal mass. One of these lesions extended into the paranasal sinuses. One case was located in the maxilla and extended to involve the maxillary sinus. Three cases were diagnosed in the mandible. The maxillary and one mandibular lesion (Case 2) resulted in significant painful irregular bone destruction with a non-healing socket and tooth mobility respectively. One mandibular lesion was asymptomatic (Case 6). The third case affecting the mandible presented as a rapidly expansile mass following a tooth extraction (Case 7). Nasal masses presented with symptoms of obstruction. Nasal masses were excised with no recurrence from up to 2–3 years of follow-up. The mandibular lesions were curetted aggressively. The oral mass in Case 7 was excised synchronously. No recurrence up to 2 years was recorded in Case 2. Follow-up information is not available for Cases 6 and 7. The maxillary lesion was not intervened surgically. The patient has persistent but stable disease for a follow-up period of 2 years. ENRDD is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis in the absence of lymph node involvement. Lesions of ENRDD resemble many other histiocytic and histiocyte-rich lesions of the head and neck. This makes the diagnosis of ENRDD challenging with the potential for under diagnosis or misdiagnosis and delay in treatment.

Keywords: Rosai-Dorfman disease, Histiocytes, Sinus histiocytosis, Lymphadenopathy, Jawbones, Nasal, Paranasal sinus, Extra nodal, Gnathic

Introduction

Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), also known as sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML), was described first by Juan Rosai and Ronald F. Dorfman in 1969 as a benign, self-limiting histiocytosis of unknown etiology [1]. The classic clinical presentation is that of a painless cervical lymphadenopathy accompanied by fever, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, weight loss, rhinorrhea and occasionally hepatosplenomegaly [1, 2]. Approximately 43% of RDD patients present without nodal involvement [3]. Extra nodal RDD (ENRDD) has been most frequently reported in the eyes, skin, nasal cavity and bones [4]. Among the extra nodal sites, the head and neck region is most commonly affected [5]. Most of the extra nodal cases of RDD in the head and neck region affect the nasal cavity, pharynx and paranasal sinuses. RDD of the paranasal sinuses and the oral cavity including the bones of the maxilla and the mandible without lymph node involvement is exceedingly rare [6]. A search of English language literature produced 38 cases of RDD of the gnathic bones, nose and paranasal sinuses without nodal involvement. We present seven additional cases of RDD of the nose, paranasal sinuses and the jawbones in the absence of nodal disease. The clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical features of ENRDD are discussed and pertinent literature is reviewed.

Materials and Methods

Seven cases of RDD of the jawbones, nose and paranasal sinuses were retrieved from the pathology services at Oral Pathology Consultants (Grosse Pointe Woods, MI), the University of Washington (Seattle, WA), Emory University (Atlanta, GA), Brigham & Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA), Joint Pathology Center (Silver Spring, MD) and Navy Medical Center (Portsmouth, VA). A sequential record of clinical features including demographic data, symptoms, physical signs, radiographic findings, treatment and follow-up of the patients when available was recorded (Table 1). A search of the English-language literature was performed using search terms Rosai-Dorfman, Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy, extranodal Rosai-Dorfman, with location combinations such as “Mandible”, “Maxilla”, “Gnathic”, “Oral”, “Nasal cavity”, “Sinus”, “Sinonasal” and “Nose”. Reports where the patient had a history of nodal disease were excluded. A total of 38 such cases were documented (Table 2).

Table 1.

Salient demographic, clinical and radiographic features of cases of ENRDD of the head and neck in the present series

| Case | Sex | Age | Location | Clinical features | Imaging study findings | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 46 | Maxilla, maxillary sinus | Pain, non-healing extraction socket | Right maxilla and sinus destruction up to pterygoid plates | Observation | Persistent disease | 2 years |

| 2 | F | 26 | Mandible | Pain, mobility of tooth #19 | Multiple irregular osteolytic foci. Scooped out appearance of superior alveolus. Tooth #19 appears extruded | Aggressive Curettage | No recurrence | 2 years |

| 3 | F | 54 | Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses | Chronic sinusitis | 3.0 × 1.5 × 3.0 cm mass, right anterior nose involving anterior and mid portions of inferior and middle turbinate | Excision | No recurrence | 2 years |

| 4 | F | 55 | Nasal cavity | Obstruction | Not available | Excision | No recurrence | 3 years |

| 5 | F | 22 | Nasal cavity | Obstruction | Not available | Excision | No recurrence | 3 years |

| 6 | M | 26 | Mandible | Incidental finding | Vaguely outlined radiolucency extending from mesial aspect of first molar tooth to mid ramus. Cortical thinning but no significant expansion. | Aggressive curettage | Not available | Not available |

| 7 | F | 38 | Mandible | Rapidly growing expansile mass | 2.5 cm × 2.3 cm × 1.3 cm mass creating a radiolucency with well-defined borders. Buccal and lingual cortical compromise | Excision of mass followed by aggressive curettage of intra bony component. | Not available | Not available |

Age range: 22–55 years (mean: 38.14 years); Gender distribution: Male: 1, Female: 6

Table 2.

Salient features of 38 previously reported cases of ENRDD

| Author/s | Number of cases | Sex | Age | Location | Presentation | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shemen et al. [25] | 1 | F | 42 | Nasal cavity, sinus, septum | Nasal mass, obstruction | Excision, radiation | Multiple recurrences | 1 year |

| Wenig et al. [26] | 6 | F | 42 | Maxillary sinus | Nasal obstruction | Excision | Multiple recurrences | 1 year |

| F | 46 | Maxillary & ethmoid sinuses | Bilateral proptosis, sinusitis, saddle nose | Excision | Progression | N/A | ||

| F | 47 | 3rd molar site soft tissue and bone | Tenderness | Excision | No recurrence | N/A | ||

| F | 54 | Nasal cavity | Epistaxis | Excision | No recurrence | N/A | ||

| F | 64 | Nasal septum | Nasal obstruction | Excision | No recurrence | N/A | ||

| M | 69 | Nasal cavity | Nasal obstruction | Excision | recurrence | 3 years | ||

| Gregor et al. [27] | 1 | M | 57 | Nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus | Nasal obstruction | Excision | No recurrence | 7 years |

| Remadi et al. [28] | 1 | M | 12 | Nasal cavity, maxillary & frontal sinus | Epistaxis, enophthalmos | Excision, steroids | Multiple recurrences | 9 years |

| Ku et al. [29] | 1 | M | 40 | Nasal cavity, septum | Epistaxis | Excision | No recurrence | 2 years |

| Kademani et al. [30] | 1 | F | 44 | Maxilla, nasal cavity | Pain maxillary premolar | Excision, steroids | No recurrence | 14 months |

| Dodson et al. [31] | 1 | F | 56 | Nasal cavity, nasopharynx | Pain, headaches, seizures, hyposmia, nasal obstruction | Excision | No recurrence | 6 months |

| Sennes et al. [32] | 2 | M | 18 | Nasal cavity, septum | Nasal obstruction, epistaxis | Excision | Recurrence | 4 years |

| M | 38 | Nasal cavity, maxillary sinus | Nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, facial swelling | Excision, steroids | Recurrence | 4 months | ||

| Gupta et al. [33] | 1 | M | 6 | Nasal cavity | Nasal obstruction | Excision | No recurrence | 2 months |

| Alawi et al. [7] | 1 | F | 32 | Mandible | Mandible swelling, pain | Excision | No recurrence | 13 months |

| Keskin et al. [34] | 1 | F | 29 | Maxillary 2nd molar alveolar ridge | Maxillary pain, swelling | None, observation | Persistent disease | 16 months |

| Dickson-Gonzales et al. [35] | 1 | F | 56 | Maxillary sinus | Hard palate Swelling | Excision | N/A | N/A |

| Ilie et al. [36] | 1 | F | 43 | Nasal cavity | Nasal obstruction, epistaxis, pain | Excision | Recurrence | 3 years |

| Sellari-Franceschini et al. [37] | 1 | F | 26 | Nasal septum | Nasal obstruction, epistaxis, anosmia | Excision, steroids | No recurrence | 19 years |

| Demicco et al. [38] | 1 | M | 18 | Maxilla | N/A | N/A | Persistent disease | 35 months |

| Ojha et al. [39] | 1 | F | 47 | Maxillary 2nd molar alveolar ridge | Maxillary pain | Excision, radiation | No recurrence | 10 months |

| Khan et al. [40] | 1 | F | 30 | Nasal cavity | Nasal obstruction, orbital protrusion, decreased vision, rhinorrhea | Excision, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, steroids, iron | N/A | N/A |

| Tekin et al. [41] | 1 | F | 23 | Mandible | Pain, swelling mandibular premolar s/p extraction | Excision | No recurrence | 3 years |

| Zhu et al. [42] | 3 | M | 27 | Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses | Headache, nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, epistaxis | Excision | Persistent disease | 2 years |

| M | 28 | Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses | Nasal obstruction, lacrimation, facial swelling | Excision, steroids | Intracranial & lung lesion, metastases | 16 months | ||

| M | 53 | Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses | Nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, epistaxis | Excision, steroids | Recurrence | 1 year | ||

| Lai et al. [43] | 1 | F | 41 | Nasal cavity, septum | Nasal obstruction, epistaxis | Excision | No recurrence | 6 weeks |

| Zhao et al. [44] | 1 | F | 11 | Nasal cavity, maxillary sinus | Nasal obstruction, facial mass | Excision | Persistent disease with regression | 25 months |

| Akyigit et al. [45] | 1 | M | 15 | Nasal septum | Difficulty breathing | Excision | No recurrence | 6 months |

| Duan et al. [8] | 7 | M | 21 | Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses | Nasal obstruction, facial asymmetry, Hyposmia | Excision | Recurrence | 5.5 years |

| M | 31 | Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses | Nasal obstruction, aural fullness, hyposmia | Excision | Recurrence | 51 months | ||

| F | 32 | Nasal septum | Nasal obstruction, dyspnea, epistaxis, hyposmia | Excision | Multiple recurrences | 5.33 years | ||

| F | 44 | Nasal septum | Epistaxis, nasal dorsum lesion | Excision | Recurrence | 39 months | ||

| F | 53 | Nasal septum | Epistaxis | Excision | No recurrence | 6 months | ||

| F | 53 | Nasal septum | Nasal dorsum lesion | Excision | No recurrence | 6.5 years | ||

| M | 58 | Nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses | Nasal obstruction, decreased vision, hyposmia | Excision | No recurrence | 10 years | ||

| Hamza et al. [46] | 1 | F | 27 | Mandible | Swelling, pain, loosening of teeth | Excision | No recurrence | N/A |

Age range: 6–69 years (mean: 38 years); Gender distribution: Male: 15, Female: 23; Site distribution of cases: nasal cavity and nasal septum: 32 cases, maxillary sinus: 14 cases, jaw bones: 8 cases

Results

Clinical and Radiographic Findings

Six cases in our series affected women and one case was diagnosed in a male. The age range was from 22 years to 55 years with a mean of 38.14 years.

Case 1

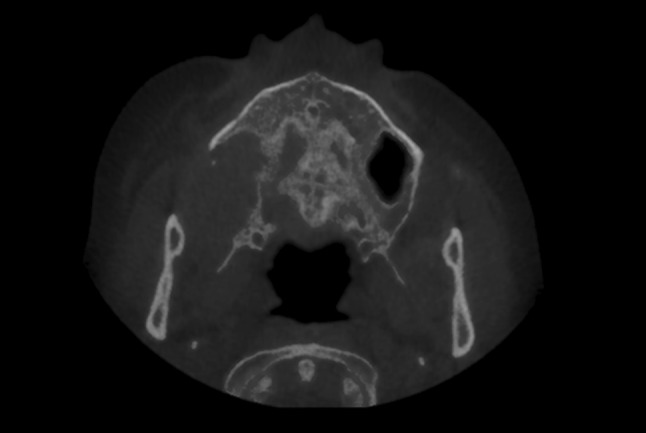

This 46-year-old female presented with pain of approximately 6 months duration and a non-healing extraction site from a maxillary molar. An axial CT showed an expansile osteolytic process of the right posterior maxilla with buccal cortical plate and tuberosity resorption and extension into the right maxillary sinus (Fig. 1). A biopsy of the posterior maxilla and maxillary sinus contents was done.

Fig. 1.

Axial CT (Case 1) demonstrating an osteolytic process of the right maxilla

Case 2

A 26-year-old female presented with pain and mobility of the lower left first molar. The symptoms were noted to be increasing gradually over 4–5 months. Radiographic examination showed multiple irregular osteolytic foci of varying size. The superior alveolus showed a scooped-out outline. Tooth #19 appeared extruded and its roots showed reduced bone support. Tooth #18 was missing, having been extracted 4–5 months before (Fig. 2). A biopsy of one of the osteolytic foci was obtained. A concurrent upper arm mass was also biopsied.

Fig. 2.

Panoramic radiograph (Case 2) demonstrating multiple osteolytic areas of left mandible. A scooped-out appearance of the superior alveolus is seen

Case 3

Patient three had over a 15-year history of chronic sinusitis which was refractory to over the counter nasal sprays and allergy medications. Nasal endoscopy showed a mass of the right nasal cavity involving the inferior turbinate. ACT scan showed a 3.0 × 1.5 × 3.0 cm mass in the right anterior nasal cavity involving the anterior and mid portions of the inferior and middle turbinates. No other masses or lesions were identified radiographically or clinically. A biopsy was obtained with a diagnosis consistent with RDD. Endoscopic excision of the right nasal cavity mass including partial right inferior turbinectomy was performed.

Case 4

Patient four had symptoms of chronic sinusitis for over 10 years with bilateral membrane removal from the maxillary and anterior ethmoid sinuses. Symptoms persisted and endoscopic antrostomy with mucous membrane removal from the bilateral maxillary and ethmoid sinuses was again performed and a diagnosis of ENRDD was given.

Case 5

Patient five had a complaint of nasal obstruction with bilateral nasal polyps. These polyps were excised and diagnosed as ENRDD on the basis of histopathological and immunohistochemical findings.

Case 6

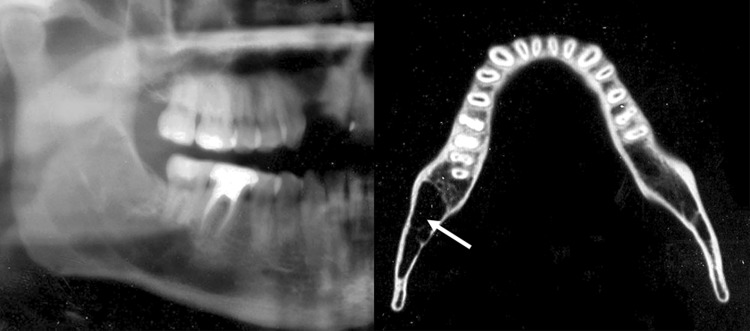

A 26-year-old male developed a radiolucent lesion of the right posterior mandible that extended from the body to the mid ramus (Fig. 3 cropped panoramic X-ray). Cortical thinning with no significant bone expansion was seen (Fig. 3 CT axial slice). The right mandibular third molar had been extracted 6–7 years ago. A biopsy was performed in the area of the extraction site.

Fig. 3.

Cropped panoramic radiograph and axial CT slice (Case 6) showing an osteolytic process of the right posterior mandible extending to the mid ramus. The axial CT slice shows lesion (arrow) causing cortical thinning but no significant expansion

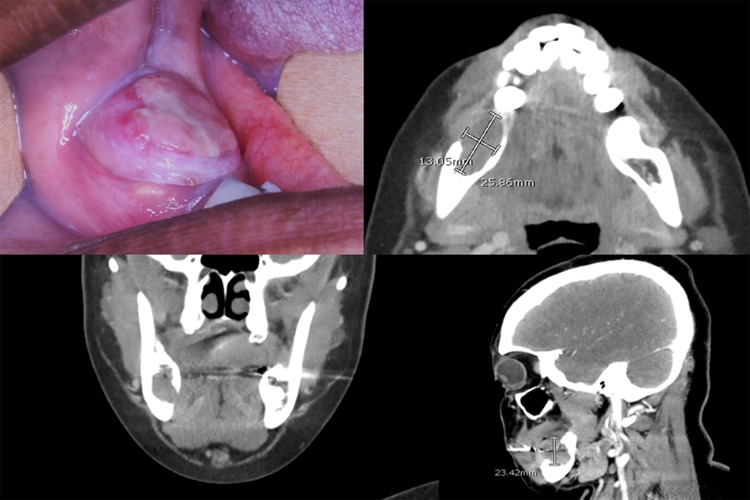

Case 7

This 38-year-old female developed a rapidly growing mass in her right posterior mandible 3.5 months following a tooth extraction. CT imaging showed a well-demarcated expansile mass with buccal and lingual cortical plate compromise (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Clinical and CT images (case 7) show a mass of the right posterior mandible causing expansion with buccal and lingual cortical plate compromise

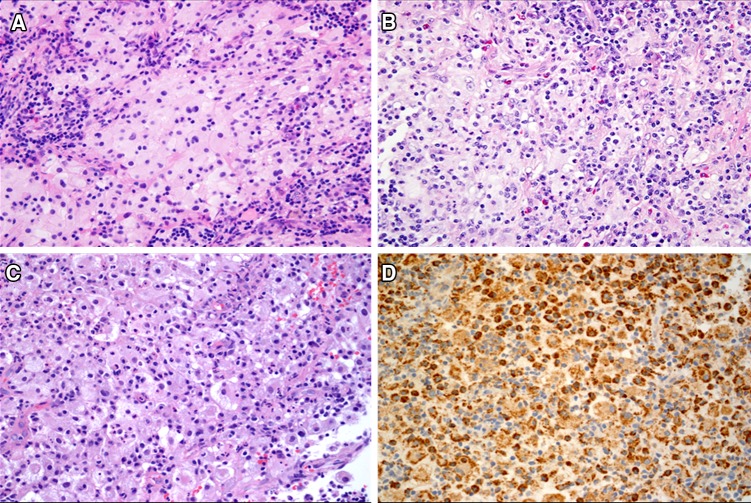

Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Findings

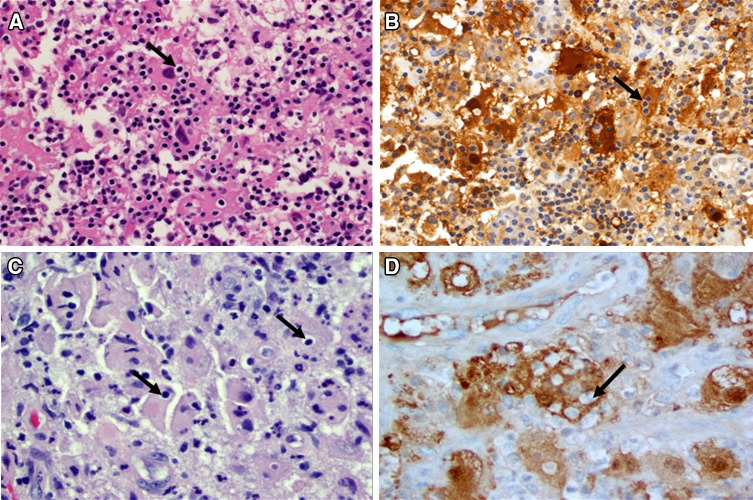

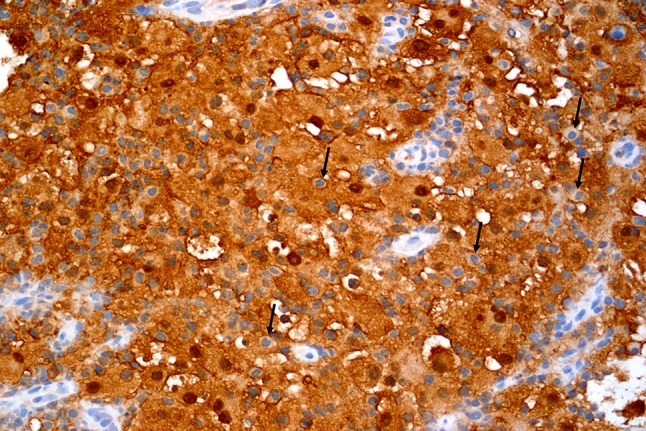

Histopathological features were fairly consistent across the seven cases. Sheets of large cells with a bright pink to slightly granular and occasionally foamy to vacuolated cytoplasm were seen. The cells showed a relatively well-defined cell membrane. A single, prominent dark nucleus was seen (Fig. 5a). Inflammation was consistently present and consisted of lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils. Eosinophils were seen in only case five (Fig. 5b). A mixed leukocytic phagocytosis was seen (Fig. 5c). Macrophage markers including CD68 (Fig. 5d), CD163 and alpha-1-antitrypsin were variably used in four cases (Cases 1, 2, 6 and 7) and were positive. Langerhans cell marker CD1a was used in only case one and two and tested negative. The cells were positive to S100 protein in all cases and phagocytosed lymphocytes (emperipolesis) remained unstained (Figs. 6, 7b and d, arrows). Emperipolesis was easier to detect in H & E stained sections in cases 6 and 7 (Fig. 7a and c respectively, arrows). The histopathological features and the immunohistochemistry reactivity were consistent with a diagnosis of Rosai-Dorfman disease in each of the cases.

Fig. 5.

a Sheets of large histiocytic cells with a well-defined cytoplasmic membrane and light eosinophilic to vacuolated cytoplasm and a single prominent nucleus are mixed with variably dense inflammation. (H & E, 20×). b Inflammatory infiltrate comprised of lymphocytes, plasma cells and neutrophils. Eosinophils were seen in only case five. (H & E, 20×). c A mixed leukocytic phagocytosis was seen in all cases. Lymphophagocytosis (emperipolesis) was not prominent (H & E, 20×). d The cells expressed strong and diffuse reactivity to CD68 (20×)

Fig. 6.

Emperipolesis is evident in S100 stained tissue (arrows) (20×)

Fig. 7.

Lymphocytic emperipolesis (arrows) is seen in H & E stained sections in Case 6 (a, 40×) and Case 7 (c, 40×). These lymphocytes appear prominent within the S100 protein positive histiocytes (b, Case 6) and (d, Case 7)

Management and Follow-Up

The mandibular lesion in case two was removed by aggressive curettage and the upper arm mass was excised. The upper arm mass was diagnosed as RDD as well. The patient is disease free through a follow-up period of 2 years. The lesion of the maxilla (case 1) is currently stable and under observation. Cases 3, 4 and 5 are disease free at post-excision intervals of 2, 3 and 3 years respectively. Mandibular lesions in Cases 6 and 7 were removed by aggressive curettage. The oral mass in Case 7 was excised simultaneously. No follow-up information is available on Cases 6 and 7.

Discussion

Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (SHML), also known as Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD), is a rare, non-neoplastic histiocytosis of unknown etiology, first described in 1969 [1]. It is usually seen in the first two decades of life with about 62% of the cases occurring in patients under 10 years of age and 81% of cases occurring in patients under 20 years of age. The age range is however from 1–69 years [6]. The age of patients in our series ranged from 22 years to 55 years with a mean of 41 years and a median of 46 years. RDD does not exhibit any predilection based on gender, race or socioeconomic status [6]. However, all patients in our series were females. The most common clinical manifestation of RDD is bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. Constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, weight loss and night sweats may also be present [7]. Approximately 43% of patients present with extranodal lesions of RDD [3, 8].

However, RDD without nodal involvement is extremely rare. The most common extranodal locations for RDD are the skin, nasal cavity, eyes and the bones [4]. Table 2 lists 38 cases of extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease (ENRDD) of the head and neck. The age of patients ranged from 6–69 years with a mean of 38 years. Females were affected more than males (23:15). The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses were by far the most common location followed by the jawbones. RDD of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses present as a polyp causing variable degrees of obstruction, swelling, facial asymmetry, nasal discharge, hyposmia, headache, epistaxis, lacrimation and proptosis. The five patients in our series denied constitutional symptoms. The two nasal cavity lesions presented as obstruction causing masses while the lesion spanning the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses presented symptoms of chronic sinusitis. The maxillary bone lesion was discovered in association with a painful non-healing extraction socket. The mandibular bone lesion also presented with pain and tooth mobility (Table 3).

Table 3.

Differential diagnosis of histopathological mimics of Rosai-Dorfman disease of the head and neck

| Disease | Histopathological features | Immunohistochemical features | Ancillary findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosai-Dorfman disease | Sheets of large cells with bright pink slightly granular to foamy cytoplasm, single prominent dark nucleus. Variable patchy inflammation with polyclonal plasma cells, reactive B and T cells. Although leukocytic phagocytosis is common, emperipolesis of lymphocytes is hard to discern |

Cells are CD68, CD163 and S100 positive (often helps highlight emperipolesis) Cells are CD1a and CD207 (Langerin) negative |

|

| Rhinoscleroma | Large macrophages with a clear to foamy cytoplasm (Mikulicz cells) admixed with lymphocytes and numerous plasma cells. Squamous metaplasia or pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of surface epithelium |

Macrophages are CD68 and CD163 positive Macrophages are S100, CD1a and CD207 negative |

Warthin-Starry silver stain shows bacteria K. rhinoscleromatis within macrophages |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Sheets of ovoid or epithelioid cells with pale cytoplasm, irregular nuclear grooves, folds or indentations (kidney/coffee bean nuclei). Prominent tissue eosinophilia to eosinophilic abscess formation. Other inflammatory cells, multinucleated cells, foamy histiocytes may be variably present |

Cells are S100, CD1a and CD207 positive Cells are CD163 negative. CD68 is variable |

Electron microscopy: Tennis racket shaped Birbeck granules |

| Central xanthoma | Loose to compact sheets of large round to oval to rarely plump spindled cells with a granular to foamy cytoplasm with vesiculated or intensely dark nuclei. Unperforated lesions may show little inflammation. Occasional multinucleated cells |

Cells are CD68 and CD163 positive Cells are S100 and CD207 negative |

|

| Erdheim-Chester disease | Foamy histiocytes within thickened bone trabeculae. Occasional multinucleated giant cells. Small clusters of Langerhans cells may be present |

Cells are CD68 and CD163 positive Small clusters of Langerhans cells will be S100 and CD1a positive (These clusters are a minor population relative to the histiocytes) |

BRAF V600E mutations in up to 100% of patients Note: A diagnosis is made only upon correlation with clinical features (upper and lower limb lesions with bone pain is most common) and identification of above mutation |

The clinical differential diagnosis of RDD of the paranasal sinuses includes rhinosinusitis, sinonasal polyps, rhinoscleroma, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s Granulomatosis). Rhinosinusitis is a common condition caused by bacterial or viral infections or environmental allergens. Symptoms include nasal stuffiness, sneezing, and drainage. Microscopic examination shows mucosal edema with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate. A predominance of eosinophils in the infiltrate suggests an allergic etiology [9]. Sinonasal polyps result from repeated rhinosinusitis. They usually occur in the nasal cavity, maxillary or ethmoid sinuses, and present with rhinorrhea, stuffiness, obstruction, and headache. Radiologically they present as multiple expansible masses within the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses. Histopathological examination shows edematous stroma with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, mucoserous glands with goblet cell hyperplasia or metaplasia, and myofibroblastic stromal cells with reactive atypia [10]. Rhinoscleroma is a granulomatous bacterial infection caused by Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. It common in Egypt, south Asia, central & south America, north & central Africa, and eastern Europe. In the US, lesions may be encountered in the immigrant population or in recent visitors to endemic areas. Patients present with nasal discharge, obstruction, expansion and deformity. Microscopic examination of infected tissue shows a granulomatous proliferation of macrophages containing silver stain positive bacteria [11]. Granulomatosis with polyangitis (GPA) is a small and medium vessel vasculitis. GPA affects the sinuses, lungs and kidneys most commonly, but lesions of the eye, ears, skin, nerves, joints, oral cavity and other organs have also been recorded. Nasal congestion, nosebleeds, shortness of breath, and bloody cough are early manifestations of GPA. Joint pain, decreased hearing, skin rashes, eye redness and/or vision changes, fatigue, fever, appetite and weight loss, night sweats, and numbness or loss of movement in the fingers, toes or limbs, oral ulcers and a strawberry gingivitis are other presenting features of GPA. Patients with GPA demonstrate elevated serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (C-ANCA) [12, 13].

RDD of the jawbones presents with intermittent pain and bone loss. A slow expansion may also be present. Radiographically, jawbone lesions of RDD may present as an ill-defined osteolytic process to variably sized multiple foci of osteolysis. The clinical and radiographic differential diagnosis of jaw lesions of RDD would include reactive, infectious and neoplastic processes such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), osteomyelitis, metastatic disease, carcinoma and lymphoma. Jaw lesions of LCH present as punched-out lucencies. Larger lesions produce a scooped out bone loss affecting the alveolus. These osteolytic foci are accompanied by pain, swelling and loosening of teeth [14]. Osteomyelitis of the jaws is usually due to uncontrolled dental infection. Pain, swelling, lymphadenopathy and other constitutional signs and symptoms of an inflammatory process are seen. Radiographically, osteomyelitis appears as a moth-eaten, mixed opaque/lucent lesion. Widening of the periodontal ligament, loss of lamina dura, and periosteal new bone formation may also be seen [14]. Jawbone metastatic disease and lymphoma may present with persistent vague pain, discomfort and tooth mobility. In advanced stages, patients may also experience numbness of lip and pathologic fractures. The diagnosis rests on histopathological examination of biopsied tissue [14, 15].

Histopathological examination of RDD shows sheets of large cells with a pink cytoplasm and a prominent nucleus characteristic of histiocytes. Inflammation is always present. Its distribution and intensity is variable. Jaw lesions in association with loose teeth may show greater amounts of inflammation that may obscure the diagnosis. RDD of the lymph nodes shows distended nodal sinuses packed with histiocytes demonstrating emperipolesis of lymphocytes. Occasionally neutrophils and red cells may also be phagocytosed. As encountered in our five cases, emperipolesis is harder to evaluate in ENRDD and is best recognized following S100 protein immunohistochemistry, where the histiocytes of RDD express strong cytoplasmic and nuclear reactivity to S100 protein. The lymphocytes within the intracytoplasmic emperipolesis vacuoles remain unstained (Fig. 4). The histiocytes are CD68, CD163 and Alpha-1-antitrypsin positive [16].

Histopathologically, RDD resembles LCH, central xanthoma, rhinoscleroma and Erdheim-Chester disease. LCH is a class I dendritic cell histiocytosis and it was reclassified as an “L” group of histiocytosis. Clonal mutations involving genes of the MAPK pathway are detected in 80% of cases [17]. A recent study showed a subgroup of cases of RDD with mutually exclusive KRAS and MAP2K1 mutations (7 cases, N = 21) with 6 out of 7 (86%) cases expressing these point mutations being localized to the head and neck [18]. The diagnosis of LCH is based on a combination of clinical and radiographic findings in association with histopathological identification of mononuclear histiocytes with a coffee bean or kidney shaped nucleus. In routine pathological diagnostic practice, detection of Birbeck granules by electron microscopy has been replaced by immunohistochemical detection of CD1a and CD207 (Langerin) in the histiocytes. Lesional tissue also shows abundant eosinophils and multinucleated giant cells [17]. Rhinoscleroma and RDD can show some overlapping features including presentation in the respiratory tract and lymph nodes and a prominent histiocytic infiltrate. Rhinoscleroma will show a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with large, vacuolated macrophages known as Mikulicz cells that harbor the bacteria made prominent with silver stains. Emperipolesis may also be seen. Cases of concurrent rhinoscleroma and RDD have been reported. Histiocytes of rhinoscleroma are S100 negative [19, 20]. Xanthoma of bone is a benign tumor consisting of a collection of granular to foamy histiocytes arranged in loose or compact sheets of large, round to oval cells. These cells may show cytoplasmic vacuolation and are CD 68 and CD 163 positive but S100 negative. [21]. Erdheim-Chester disease shows CD68 positive and S100 negative histiocytes with a granular cytoplasm. The disease affects patients between ages of 40 and 60 years. Patients present with lower leg and upper arm bone pain, headaches, seizures, cognitive impairment, diabetes insipidus, kidney and heart disease. [22].

RDD that involves the jawbones and teeth may easily be misinterpreted as dental-related inflammation.

RDD may demonstrate increased numbers of IgG4 + plasma cells. However, in the absence of fibrosis with at least a focal storiform pattern, eosinophils in the inflammatory infiltrate and an obliterative phlebitis, the possibility of IgG4-related disease can be excluded [23, 24].

ENRDD of the jaws and paranasal sinuses is an indolent, self-limiting disease. Some cases of ENRDD have undergone spontaneous resolution. Observation and monitoring may be adequate in asymptomatic patients. Masses of the nasal and paranasal sinuses producing symptoms of obstruction are treated by conservative excision. Radiation therapy has also been used with some success, but this is generally restricted to patients with vital organ involvement [8].

Conclusion

RDD or SHML is a relatively rare histiocytosis of unknown origin. A diagnosis of RDD is rarely suspected in the absence of nodal involvement. Primary jaw, nasal and paranasal lesions , ENRDD are clinically mistaken for other pathologic processes with a resultant delay in diagnosis and management. Histopathologically, ENRDD of the head and neck shows relatively more mixed inflammation. Lymphophagocytosis (emperipolesis) is not visualized as readily as in nodal disease. Due to these features, ENRDD of the head and neck resembles a broad range of histiocyte rich common inflammatory conditions and other neoplastic processes that need to be excluded to arrive at a correct diagnosis.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of Army/Navy/Air Force, Department of Defense, or US Government.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Junu Ojha, Email: juojha@gmail.com.

Yeshwant B. Rawal, Email: ybrawal@gmail.com

Jason L. Hornick, Email: jhornick@bwh.harvard.edu

Kelly Magliocca, Email: kmagliocca@emory.edu.

David R. Montgomery, Email: montgomdds@gmail.com

Robert D. Foss, Email: robert.d.foss.ctr@mail.mil

Kevin R. Torske, Email: kevin.r.torske.mil@mail.mil

Brent Accurso, Email: brent.accurso@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a newly recognized benign clinicopathological entity. Arch Pathol. 1969;87(1):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: a pseudolymphomatous benign disorder. Analysis of 34 cases. Cancer. 1972;30(5):1174–1188. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197211)30:5<1174::aid-cncr2820300507>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang E, Anzai Y, Paulino A, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease presenting with isolated bilateral orbital masses: report of two cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(7):1386–1388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaitonde S. Multifocal, extranodal sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: an overview. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(7):1117–1121. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-1117-MESHWM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bist SS, Bisht M, Varshney S, Kishore S. Rosai-Dorfman disease. Ear Nose Throat J. 2008;87(1):16–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foucar E, Rosai J, Dorfman RF. Sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy: current status and future directions. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(8):1211–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alawi F, Robinson BT, Carrasco L. Rosai-Dorfman disease of the mandible. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102(4):506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duan HG, Zheng CQ, Wang DH, Ding GQ, Luo JQ, Zang CP, et al. Extranodal sinonasal Rosai-Dorfman disease: a clinical study of 10 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(9):2313–2318. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad N, Zacharek MA. Allergic rhinitis and rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(2):267–281. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2007.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Passàli D, Bellussi L, Hassan HA, Mösges R, Bastaic L, Bernstein JM, et al. Consensus conference on nasal polyposis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2004;24(2 Suppl 77):3–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson K, Parham K. Nasal and paranasal sinus infections. In: Hupp J, editor. Head, neck, and orofacial infections. Elsevier: St. Louis; 2016. pp. 248–270. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falk RJ, Gross WL, Guillevin L, Hoffman G, Jayne DR, Jennette JC, et al. Granulomatosis with polyangitis: an alternative name for Wegener’s granulomatosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(4):704. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.150714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkielman JD, Lee AS, Hummel AM, Viss MA, Jacob GL, Homburger HA, et al. ANCA are detectable in nearly all patients with active severe Wegener’s granulomatosis. Am J Med. 2007;120(7):643.e9–643.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquot JE. Oral and maxillofacial pathology. 4. St. Louis: Saunders; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bugshan A, Kassolis J, Basile J. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the mandible: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2015;8(3):451–455. doi: 10.1159/000441469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantilla JG, Goldberg-Stein S, Wang Y. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease: clinicopathologic series of 10 patients with radiologic correlation and review of the literature. Am J Clin Pathol. 2016;145(2):211–221. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqv029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haroche J, Cohen-Aubart F, Rollins BJ, Donadieu J, Charlotte F, Idbaih A, et al. Histiocytoses: emerging neoplasia behind inflammation. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(2):113–125. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garces S, Medeiros LJ, Patel KP, Li S, Pina-Oviedo S, Li J, et al. Mutually exclusive recurrent KRAS and MAP2K1 mutations in Rosai-Dorfman disease. Mod Pathol. 2017;30(10):1367–1377. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumari JO. Coexistence of rhinoscleroma with Rosai-Dorfman disease: is rhinoscleroma a cause of this disease? J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126(6):630–632. doi: 10.1017/S0022215112000552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasper HU, Hegenbarth V, Buhtz P. Rhinoscleroma associated with Rosai-Dorfman reaction of regional lymph nodes. Pathol Int. 2004;54(2):101–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2004.01597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rawal YB, Chandra SR, Hall JM. Central xanthoma of the jaw bones: a benign tumor. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11(2):192–202. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0764-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tzankov A, Kremer M, Leguit R, Orazi A, van der Walt J, Gianelli U, et al. Histiocytic cell neoplasms involving the bone marrow: summary of the workshop cases submitted to the 18th Meeting of the European Association for Haematopathology (EAHP) organized by the European Bone Marrow Working Group, Basel 2016. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(11):2117–2128. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3436-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, Yi EE, Sato Y, Yoshino T, Klöppel G, et al. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(9):1181–1192. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Menon MP, Evbuomwan MO, Rosai J, Jaffe ES, Pittaluga S. A subset of Rosai-Dorfman disease cases show increased IgG4-positive plasma cells: another red herring or a true association with IgG4-related disease? Histopathology. 2014;64(3):455–459. doi: 10.1111/his.12274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shemen L, D′Anton M, Klijian A, Toth I, Galantich P. Rosai-Dorfman disease involving the premaxilla. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991;100(10):845–851. doi: 10.1177/000348949110001011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wenig BM, Abbondanzo SL, Childers EL, Kapadia SB, Heffner DR. Extranodal sinus histiocytosis with massive lymphadenopathy (Rosai-Dorfman disease) of the head and neck. Hum Pathol. 1993;24(5):483–492. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90160-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregor RT, Ninnin D. Rosai-Dorfman disease of the paranasal sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108(2):152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Remadi S, Anagnostopoulou ID, Jlidi R, Cox JN, Seemayer TA. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease in childhood. Pathol Res Pract. 1996;192(10):1007–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0344-0338(96)80042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ku PK, Tong MC, Leung CY, Pak MW, Van Hasselt CA. Nasal manifestation of extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease–diagnosis and management. J Laryngol Otol. 1999;113(3):275–280. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100143786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kademani D, Patel SG, Prasad ML, Huvos AG, Shah JP. Intraoral presentation of Rosai-Dorfman disease: a case report and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93(6):699–704. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.123495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dodson KM, Powers CN, Reiter ER. Rosai Dorfman disease presenting as synchronous nasal and intracranial masses. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24(6):426–430. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0709(03)00090-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sennes L, Koishi H, Cahali R, Sperandio F, Butugan O. Rosai-Dorfman disease with extranodal manifestation in the head. Ear Nose Throat J. 2004;83(12):844–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta L, Batra K, Motwani G. A rare case of Rosai-Dorfman disease of the paranasal sinuses. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;57(4):352–354. doi: 10.1007/BF02907713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keskin A, Genç F, Günhan OJ. Rosai-Dorfman disease involving maxilla: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(12):2563–2568. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickson-González SM, Jiménez L, Barbella RA, Mota-Gamboa JD, Rodríguez-Morales AJ, Vals J, Molina A. Maxillofacial Rosai-Dorfman disease in a newly diagnosed HIV-infected patient. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12(2):219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ilie M, Guevara N, Castillo L, Hofman PJ. Polypoid intranasal mass caused by Rosai-Dorfman disease: a diagnostic pitfall. J Laryngol Otol. 2010;124(3):345–348. doi: 10.1017/S0022215109990818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sellari-Franceschini S, Lenzi R, Tognetti A, Seccia V. Extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease of bone and nose: a case report and review of literature. Pathologica. 2010;102(2):62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demicco EG, Rosenberg AE, Björnsson J, Rybak LD, Unni KK, Nielsen GP. Primary Rosai-Dorfman disease of bone: a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(9):1324–1333. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ea50b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ojha J, McIlwain R, Said-Al Naief N. A large radiolucent lesion of the posterior maxilla. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2010;110(4):423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khan AA, Siraj F, Rai D, Aggarwal S. Rosai-Dorfman disease of the paranasal sinuses and orbit. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2011;4(2):94–96. doi: 10.5144/1658-3876.2011.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tekin U, Tüz HH, Günhan O. Reconstruction of a patient with Rosai-Dorfman disease using ramus graft and osseointegrated implants: a case report. J Oral Implantol. 2012;38(1):79–83. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-10-00056.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu F, Zhang JT, Xing XW, Wang DJ, Zhu RY, Zhang Q, et al. Rosai-Dorfman disease: a retrospective analysis of 13 cases. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345(3):200–210. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3182553e2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lai KL, Abdullah V, Ng KS, Fung NS, van Hasselt CA. Rosai-Dorfman disease: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Head Neck. 2013;35(3):E85–E88. doi: 10.1002/hed.21930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao XC, McHugh J, Thorne MC. Pathology quiz case 2: extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease (RDD)of the maxillary sinus. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(5):529–531. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.2864a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Akyigit A, Akyol H, Sakallioglu O, Polat C, Keles E, Alatas O. Rosai-Dorfman disease originating from nasal septal mucosa. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/232898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamza A, Zhang Z, Al-Khafaji B. Solitary extranodal Rosai-Dorfman disease of the mandible: an exceedingly rare presentation. Autops Case Rep. 2018;8(3):e2018036. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]