Abstract

CRISPRs are a promising tool being explored in combating exogenous retroviral pathogens and in disabling endogenous retroviruses for organ transplantation. The Cas12a and Cas13a systems offer novel mechanisms of CRISPR actions that have not been evaluated for retrovirus interference. Particularly, a latest study revealed that the activated Cas13a provided bacterial hosts with a “passive protection” mechanism to defend against DNA phage infection by inducing cell growth arrest in infected cells, which is especially significant as it endows Cas13a, a RNA-targeting CRISPR effector, with mount defense against both RNA and DNA invaders. Here, by refitting long terminal repeat retrotransposon Tf1 as a model system, which shares common features with retrovirus regarding their replication mechanism and life cycle, we repurposed CRISPR-Cas12a and -Cas13a to interfere with Tf1 retrotransposition, and evaluated their different mechanisms of action. Cas12a exhibited strong inhibition on retrotransposition, allowing marginal Tf1 transposition that was likely the result of a lasting pool of Tf1 RNA/cDNA intermediates protected within virus-like particles. The residual activities, however, were completely eliminated with new constructs for persistent crRNA targeting. On the other hand, targeting Cas13a to Tf1 RNA intermediates significantly inhibited Tf1 retrotransposition. However, unlike in bacterial hosts, the sustained activation of Cas13a by Tf1 transcripts did not cause cell growth arrest in S. pombe, indicating that virus-activated Cas13a likely acted differently in eukaryotic cells. The study gained insight into the actions of novel CRISPR mechanisms in combating retroviral pathogens, and established system parameters for developing new strategies in treatment of retrovirus-related diseases.

Subject terms: Molecular biology, Cell biology

Introduction

The CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat) and CRISPR-associated systems (Cas) are adaptive immunity mechanism against invading viruses or plasmids, which originated and evolved in bacteria and archaea1,2. In recent years, they have emerged as an important and promising tool being explored in combating foreign retroviral pathogens and in inactivating endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) for organ transplantation. CRISPR was considered advantageous to the previous technologies, such as TALEN3, ZFN4,5, and RNAi6,7, as it is easier to handle, more efficient, and less expensive. Both endogenous and exogenous retroviruses are known to be causes of major health issues for people, and risk factors for organ transplantation and xenotransplantation8–11. Well-known examples include acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and HIV-associated neurological disorders (HAND) caused by HIV-112–15, leukemia/lymphoma and autoimmune diseases induced by Human T-lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1)16, and cancer and autoimmunity associated with the less known Human Endogenous Retrovirus K (HERV-K)17,18. Among CRISPR systems that have been tested, class 2 type II CRISPR-Cas9 was the first engineered to combat retroviral pathogens in animals and plants. CRISPR-Cas9 was reprogrammed to targeting HIV-1 under a Tat-feedback regulation, leading to ablation of HIV-1 at a very early stage of replication in the course of the acute infection, and in latently infected cells19. CRISPR-Cas9 was found to be potent for inactivating latent HIV-1 in infected cells by targeting HIV-1 essential genes or long terminal repeat (LTR)20,21. Cas9 was used as an efficient research tool to perturb retroviral LTRs in human cells to determine their long-range effects on gene regulation22. CRISPR-Cas9 was also explored for disabling of ERVs in pigs to create ERV-inactivated animals for xenotransplantation, which is an essential step to address clinical safety issue23. The targeted deletion of retrotransposon Tos17 in rice using CRISPR-Cas9, resulted in the new generation of plant free of active Tos17 retrotransposon24.

The recently emerged class 2 type V CRISPR-Cas12a (also called Cpf1) has some intrinsic features that make it an important alternative to Cas925–29. Cas12a has a different capacity for targeting AT-rich genomic regions, which expands that of Cas9, due to its different restrictive requirement for protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence25,30. It possesses endogenous RNase activity enabling the generation of single or multiplex CRISPR RNA (crRNA) without the need for involving other RNA nucleases for processing31–34. Besides, Cas12a requires a much shorter crRNA (~41 nucleotides)25,35 than the fused crRNA-tracrRNA of Cas9 (~100 nucleotides)36,37, thus simplifying its use and assay development, such as chemical synthesis and modification of crRNA38. Further, Cas12a was reported to have better targeting precision than Cas9 in a number of genome editing experiments26,39. Despite all these superior attributes, there has been no reported study of Cas12a application in retrovirus/retrotransposon intervention. Therefore, we are severely limited in knowledge and capacity in applying this valuable CRISPR tool for combating retrovirus.

More recently, the class 2 type VI CRISPR-Cas13 group of effectors were discovered and found to possess the unique ability to specifically target and cleave single-stranded RNA rather than double-stranded DNA substrates40–43. They present the novel capacity to bind RNA molecules guided by crRNAs that contain a fixed direct repeat (DR) and variable spacer sequences. In addition, some members of them, e.g., LshCas13a40, were proved to be able to process pre-crRNA into crRNAs, thus facilitating their application by simplifying the production of crRNAs. Since its first discovery in 2016, CRISPR-Cas13 has seen actions in nucleic acid detection44, gene transcript tagging and tracking45, and gene transcript editing and mutation correction46,47, etc. Many efforts have also been focused on utilizing Cas13a in engineering RNA virus resistance in plants. LshCas13a was shown to confer resistance to TuMV infections in Nicotiana benthamiana and Arabidopsis thaliana in transient assays and in stable-expression lines48,49. Immunity was also established using Cas13a in potato against the RNA virus, Potato virus Y (PVY), and in rice against both Southern Rice Black-Streaked Dwarf Virus (SRBSDV) and Rice Stripe Mosaic Virus (RSMV)50,51.

Lately CRISPR-Cas13a was reported to provide hosts with immunity against DNA phage infection by halting the growth of infected cells in Listeria populations (termed passive protection), in addition to its ability to target and cleave RNA virus52. The nonspecific RNase activity of activated Cas13a was believed to be involved in the passive protection mechanism, which aborted the infectious cycle in bacterial populations and provided cross-protection for host cells against mutant escaper virus as well. This passive protection mechanism is particularly significant and powerful in that it endows Cas13, an RNA-targeting CRISPR effector, with mount defense against both RNA and DNA invaders. To build on this, it is reasonable to suspect that CRISPR-Cas13a may provide a potent defense against retroviruses, which transit between DNA and RNA forms in their life cycle, by either directly targeting RNA intermediates, or halting viral propagation with the passive protection mechanism. A particular aim of the current study was to test this hypothesis and investigate the system parameters in applying Cas13a to retrovirus interference, which has not been reported before.

LTR retrotransposons and retroviruses share many common features regarding their genome structure, replication mechanism, and life cycle53,54. Both LTR retrotransposons and retroviruses replicate via reverse transcription and propagate by integrating into the host’s genome, which rely on the host transcription and translation machinery. Most LTR retrotransposons lose extracellular mobility and lack a functional envelope gene (ENV), but contain gag, protease (PR), reverse transcriptase (RT), and integrase genes (IN) that are arranged in a polycistron open reading frame (ORF), flanked by LTRs. LTR retrotransposons are abundant in genomes of some animals and plants. For example, LTR retrotransposons occupy ~8% and ~10% of the human and mouse genomes, respectively55,56. In the current study, using LTR retrotransposon Tf1 as a model system57,58, we explored the two CRISPR systems: class 2 type V CRISPR-Cas12a and type VI CRISPR-Cas13a, in interference with Tf1 retrotransposition using different mechanisms of CRISPR action. To test CRISPR-Cas12a, we first overcame the lack of Cas12a system in Schizosaccharomyces pombe by implementing and optimizing Cas12a gene editing systems in S. pombe. Second, we constructed a series of Tf1-splicing reporters by refitting the Tf1 retrotransposon with artificial introns. This system enabled the Tf1 cDNA intermediates that were reverse-transcribed from spliced-RNA, to be specifically targeted by Cas12a with designed crRNAs. While both Cas12a and Cas13a were robust in intervention with Tf1 retrotransposition, they had varying efficiencies and unequal characters in inhibition of Tf1 transposition, owing to the intrinsic differences in their nature of molecular action. By implementing and testing the versatile systems of CRISPR-Cas12a and -Cas13a, we established their system parameters for the different action mechanisms on Tf1 interference in S. pombe.

Results and discussion

Implementing and optimizing CRISPR-Cas12a editing system in S. pombe

To implement Cas12a system in S. pombe and optimize its gene editing efficiency, expression constructs of Francisella novicida Cpf1 (FnCpf1) and Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006 Cpf1 (LbCpf1) were generated with pDUAL-HFF1 vector (Supplementary Fig. S1). The expression constructs of FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 were placed in the LEU1 locus in S. pombe chromosome II by homologous recombination (HR)59 (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. S2). The impact of FnCpf1 or LbCpf1 on growth of S. pombe was assessed. The transformed strains were found to grow at rates similar to the isogenic control strain in Edinburgh minimal medium (EMM) (Fig. 1b). Therefore, the presence of a single copy of FnCpf1 or LbCpf1 gene had no detectable impact on the growth of S. pombe cells.

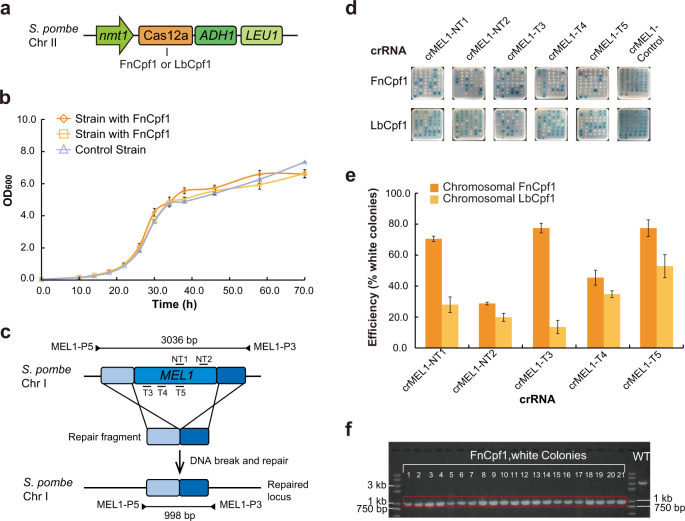

Fig. 1. Implementation of Cas12a editing system in S. pombe and editing of MEL1 gene.

a Schematic representation of the S. pombe chromosomal locus with integrated Cas12a constructs. b Growth in liquid culture media (EMM + uracil) of S. pombe strains expressing FnCpf1 or LbCpf1, compared to the control strain with blank insertion at the same locus. They had an average double time of 4.1, 4.6 and 4.5 h, respectively. Data are means ± SEM (n = 4 independent experiments). c Schematic representation of MEL1 gene editing. crRNAs were designed to target five sites (NT1, NT2, T3, T4, and T5) within MEL1 gene. The DNA cut by Cas12a is repaired with the repair fragment by HR. The arrows denote the primers, MEL1-P5 and MEL1-P3, and their PCR products for diagnostic experiments. d The editing efficiency on MEL1 gene with five different crRNAs, estimated by formation of white- and blue-colored colonies, assayed on agar plates containing the X-α-Gal. e Efficiency of genome editing on MEL1 gene with five different crRNAs. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 3. f Diagnostic PCR products of mel1 mutants (white colonies) generated from FnCpf1 editing, showing 998-bp in size. They are compared with the wild-type (WT) product, 3036-bp in size. Primer sets MEL1-P5 and MEL1-P3 (c) were used for PCR.

The genome editing efficiency of FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 was determined by editing MEL1 (SPAC869.07c) gene through introducing MEL1-targeting crRNA constructs (Supplementary Fig. S3a) into FnCpf1- or LbCpf1-expressing strains. The MEL1 gene encodes the α-galactosidase in S. pombe, which is secreted and readily assayed on agar plates containing the colorimetric substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-α-galactopyranoside (X-α-Gal)60,61. While wild-type S. pombe colonies displayed blue color, the loss-of-function mel1 mutants resulted in white colonies on X-α-Gal plates. We designed two nontargeting control crRNAs, and ten crRNAs (five for each Cas12a) for targeting FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 to five different regions of MEL1 gene in S. pombe, three on the template strand (T strand) and two on the nontemplate strand (NT strand) in its ORF (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. S3b). The editing efficiency for FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 was estimated by comparing the numbers of white-colored and blue-colored colonies. The two Cas12a had varying editing efficiencies on MEL1, ranging from 29 to 77% for FnCpf1, and 14 to 55% for LbCpf1, respectively (Fig. 1d, e and Supplementary Fig. S3b), compared to 50−98% editing efficiency for Cas9 in targeting a different gene, ADE6 in S. pombe62. While both Cas12a worked effectively in S. pombe, FnCpf1 apparently generated mel1 mutants at a higher rate than LbCpf1 for all the five targeted sites. Thus, for the current study, we chose FnCpf1 for subsequent experiments in S. pombe. It was known that the editing efficiency of Cas12a could be influenced by many factors in different organisms, e.g., base contents, sequence bias, PAM sequences, epigenetic state of targets, etc31. For example, it was previously found in rice that LbCpf1 exhibited a better editing efficiency than FnCpf1 on three endogenous genes34.

The loss-of-function mel1 mutants generated from Cas12a editing were further examined by PCR analysis and sequencing of mel1 PCR products (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. S4). The PCR products of 41 randomly picked mel1 mutants from either FnCpf1 or LbCpf1 editing indicated that mel1 mutants were all repaired via HR. While repairing via both HR and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) for CRISPR-Cas9 editing in S. pombe were documented previously62, in the case of Cas12a editing, however, NHEJ was not observed to be involved in MEL1 editing by either FnCpf1 or LbCpf1 in S. pombe. The observed high efficiency for HR may be the result of long homologous arms (~500 bp) as it was indicated that increase in HR efficiency was associated with longer homologous arms63–65.

To optimize the Cas12a system for editing in S. pombe, we further varied FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 expression levels using episomal multicopy plasmid66 (Supplementary Fig. S5) and examined their efficiencies targeting the same five sites on MEL1 gene. The increased LbCpf1 expression (while crRNA levels remained constant) in S. pombe resulted in an increased editing efficiency for four of the five targeted sites in MEL1 gene of crRNA (Supplementary Fig. S6c). This observation in S. pombe is similar to that of Cas9 in previous studies, where Cas9 expression levels were found to be positively correlated with editing efficiency67,68. To our surprise, the increased FnCpf1 expression in S. pombe resulted in a decreased editing efficiency for four of the five targeted sites in MEL1 gene of crRNA (Supplementary Fig. S6b). To rule out the possibility that the reduced editing efficiency was caused by possible toxicity of high FnCpf1 level in S. pombe cells, we further examined the growth of S. pombe strains with either FnCpf1-expressing multicopy plasmid (pDUAL-HFF1-FnCpf1) or the control plasmid (pDUAL-HFF1). They were found to grow at similar rates in EMM with glucose as carbon source (Supplementary Fig. S7), indicating no toxicity on S. pombe growth with increased FnCpf1 expression.

Construction of multiple Tf1-splicing reporters for retrotransposition interference analysis in S. pombe

The retrotransposon Tf1 can mobilize in S. pombe in a manner similar to retroviruses, through synthesis of RNA intermediates, virus-like particle (VLP) formation and reverse transcription, followed by integration of DNA intermediates into host genome54. To facilitate analysis of interference with retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas12a, we constructed Tf1-G418R retrotransposition reporter systems in S. pombe, which were modified based on scheme from previous studies47,69. A geneticin (G418) resistance gene NEO had been placed in Tf1 genome just upstream of 3′-LTR, but in the opposite orientation to Tf1 transcription. Then, by design, we inserted an artificial intron element into the ORF of NEO gene in opposite orientation to the NEO transcript, which would align in the same orientation to that of Tf1 (Fig. 2a). When the artificial intron is removed upon splicing of Tf1 transcripts, the resulting retrotransposed Tf1 would make host cells G418-resistant. The reporter system was designed to allow the original Tf1 (carried by plasmids) and reverse-transcribed Tf1 DNA (before or after integration into S. pombe genome) to be distinguished and specifically targeted. For Cas12a-targeting reverse-transcribed Tf1 cDNA, we chose four sites with nearby PAM sequences in the NEO gene for inserting the artificial intron, respectively (Fig. 2b; Materials and methods), from which splicing products could be specifically targeted with designed crRNAs.

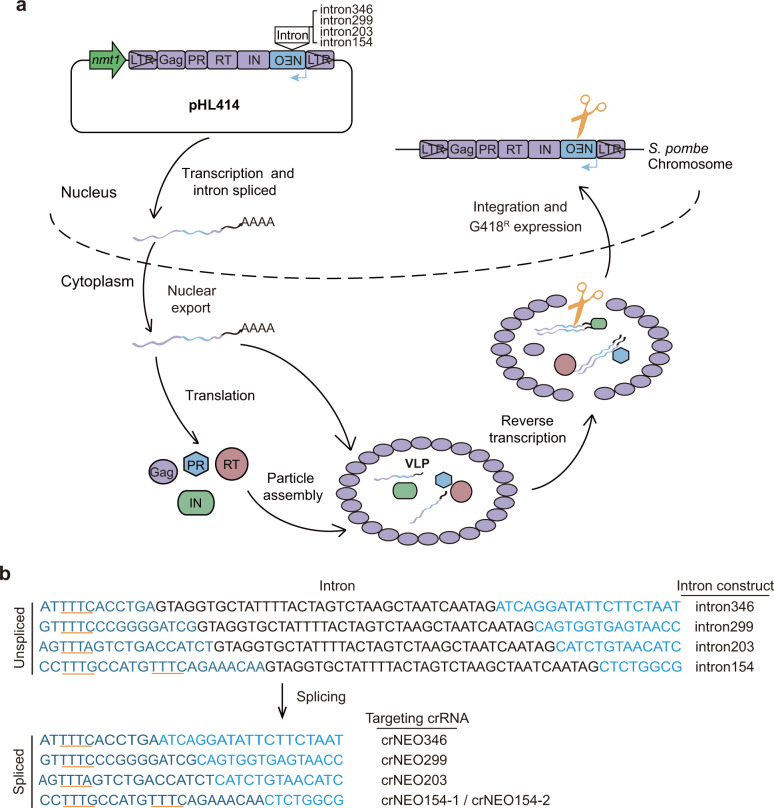

Fig. 2. Design and construction of Tf1-splicing reporter system for retrotransposition.

a Schematic representation of life cycle for Tf1-splicing reporter. The NEO gene was placed in Tf1 genome upstream of 3′-LTR, but would transcribe in the opposite orientation to Tf1 transcription (denoted by a blue arrow). Four different artificial introns were designed to be inserted in NEO gene, respectively, aligned in the same orientation to that of Tf1. Scissors denotes Cas12a-targeting sequences of NEO gene formed from splicing. nmt1 nmt1 promoter, Gag gag protein, PR protease, RT reverse transcriptase, IN integrase, NEO G418 resistance gene. b Schematic representation of four NEO gene constructs with artificial intron (black letters) in different insertion sites and their splicing products. The sequences formed via splicing are targeted by designed crRNAs (denoted to the right). The five PAM regions for Cas12a targeting are underlined in orange.

Interference with Tf1 retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas12a resulted in marginal transposition activities

To investigate interference with Tf1 retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas12a, we designed five crRNA constructs that specifically targeted the four sequence fragments (generated via splicing) of DNA intermediates, respectively (Fig. 2b). CRISPR-Cas12a was previously shown to act on DNA substrate, and had no editing activity on RNA molecules70. The five crRNAs for FnCpf1 were placed in the same reporter plasmid under the control of rrk1 promoter, respectively62 (Fig. 3a). We then transformed these reporter plasmids into the FnCpf1-carrying S. pombe strain that we generated earlier.

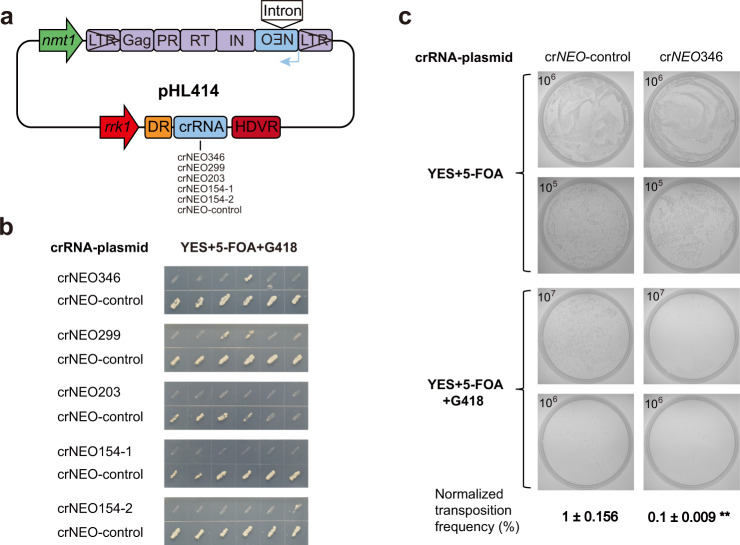

Fig. 3. Interference of Tf1 retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas12a.

a Schematic representation of six crRNA constructs for Cas12a targeting, for which the crRNA expression cassette was inserted into the Tf1-carrying pHL414 plasmid (Supplementary Table S4). crNEO-control contains nontargeting random sequence. rrk1 rrk1 promoter, DR direct repeat of crRNA, HDVR hepatitis delta virus ribozyme. b “Transfer-and-patch” assay for detection of Tf1 retrotransposition using plates containing YES media with 5-FOA and G418. The effects of the five different crRNAs and their control crNEO-control were shown side by side. c Estimation of Tf1 retrotransposition efficiency by colony-forming assay. Cells were plated in replicates to YES plates with either 5-FOA only or 5-FOA + G418. The values in the upper-left corner indicate the diluted cell concentration (cells/mL), from which 100 μL were plated (Materials and methods). Transposition efficiencies for crRNA crNEO346 and crNEO-control were estimated by comparing the number of formed colonies between the two plate conditions (Supplementary Data S2). The efficiency values were then normalized with that of crNEO-control as “1%”. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments; **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test against crNEO-control).

Tf1 transposition was initiated by withdrawing thiamine from media, prompting Tf1 transcription under nmt1 promoter. Retrotransposition efficiency was assayed by counting S. pombe colonies in YES plates containing 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) and G41869. Using the “transfer-and-patch” assay69 and comparing to the nontargeting control crRNA (crNEO-control), we observed dramatically reduced Tf1 retrotransposition with all five targeting crRNAs (Fig. 3b), indicating that Cas12a (FnCpf1) strongly inhibited Tf1 retrotransposition. While there was almost no Tf1 transposition with crRNAs crNEO203, crNEO154-1 and crNEO154-2, residual levels of retrotransposition occurred with crNEO299 and crNEO346.

To more accurately estimate the inhibition on Tf1 retrotransposition, we then measured the retrotransposition frequency for crRNA crNEO346 that had the least inhibitory effect among the five, using the colony-forming assay69. A normalized transposition frequency of 0.1 ± 0.009% was recorded for crNEO346. Compared to that of 1 ± 0.156% for the nontargeting control crRNA, the result represented an inhibition of 90% on Tf1 retrotransposition (Fig. 3c).

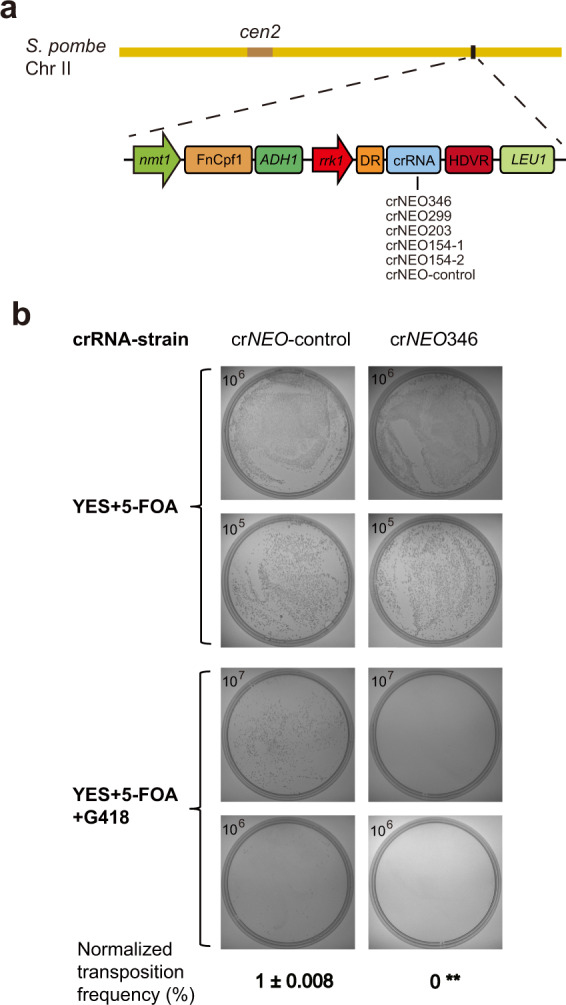

Prolonged crRNA targeting eliminated residual Tf1 retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas12a

CRISPR-Cas12a was shown to strongly inhibit Tf1 retrotransposition, allowing residual levels of transposition activities for some crRNA constructs. We reasoned that the “leaked” residual activities could be due to a lasting pool of Tf1 RNA/DNA intermediates, more persistent than crRNA and likely protected within VLPs, that remain to be further explored. That is, after the S. pombe cells were transferred to 5-FOA plates to remove pHL414 plasmids carrying Tf1, the crRNAs transcribed from the same vectors also wound down in the cells. As a result, the remnant Tf1 intermediates could enable residual retrotransposition at the time when crRNA molecules were depleted. We sought to test whether we can remove the residual Tf1 retrotransposition with prolonged crRNA targeting. Therefore, we generated six new S. pombe strains by integrating the five targeting and one nontargeting control crRNA cassettes into chromosome II at the site near FnCpf1 gene, respectively (Fig. 4a). These constructs enabled persistent crRNA expression even after Tf1-carrying plasmids were lost by 5-FOA treatment. The results showed that the persistent presence of the five crRNAs led to complete elimination of the residual Tf1 transposition activities by Cas12a (Supplementary Fig. S8). We also quantitatively assessed the Tf1 retrotransposition frequencies for crRNA crNEO346. Its normalized transposition frequency was reduced to 0 (100% inhibition), in comparison to the nontargeting crRNA control that stood at 1 ± 0.008% (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4. Prolonged crRNA targeting eliminated residual Tf1 retrotransposition by Cas12a.

a Schematic representation of six different crRNA constructs integrated into chromosome II in the six new S. pombe strains. crNEO-control contains nontargeting random sequence. cen2 centromere. b Estimation of Tf1 retrotransposition efficiency by colony-forming assay. Cells were plated in replicates to YES plates with either 5-FOA only or 5-FOA + G418. The values in the upper-left corner indicate the diluted cell concentration (cells/mL), from which 100 μL were plated (Materials and methods). Transposition efficiencies for the persistent presence of crNEO346 and crNEO-control were estimated by comparing the number of formed colonies between the two plate conditions (Supplementary Data S2). The efficiency values were then normalized with that of crNEO-control as “1%”. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments; **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test against crNEO-control).

Interfering with Tf1 retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas13a via targeting its RNA intermediates

Tf1 undergoes retrotransposition in S. pombe via RNA intermediates57,58,71, which are important target for intervention. LshCas13a was shown to have editing activity on single-strand RNA but not on DNA molecules45. We hence investigated CRISPR-Cas13a for interference with Tf1 retrotransposition. We took use of the LshCas13a-carrying S. pombe strain that we generated previously47, for which a single copy of LshCas13a gene was integrated in chromosome II at the LEU1 locus. The Tf1 retrotransposition reporter plasmid (pHL414) was modified to contain crRNAs for LshCas13a targeting. Three crRNA constructs, two targeting different regions of Tf1 transcripts and one nontargeting control, were placed under the control of rrk1 promoter, respectively (Fig. 5a). The modified plasmids were then transformed into the LshCas13a-carrying S. pombe strain.

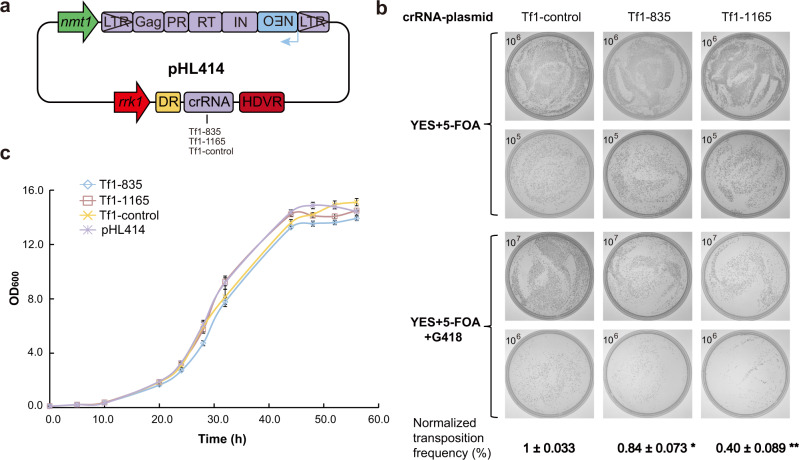

Fig. 5. Interfering with Tf1 retrotransposition by CRISPR-Cas13a via targeting its RNA intermediates.

a Schematic representation of three crRNA constructs for Cas13a targeting, for which the crRNA expression cassette was inserted into the Tf1-carrying pHL414 plasmid (as in Fig. 3a) (Supplementary Table S4). Tf1-control contains nontargeting random sequence. b Estimation of Tf1 retrotransposition efficiency by colony-forming assay. Cells were plated in replicates to YES plates with either 5-FOA only or 5-FOA + G418. The values in the upper-left corner indicate the diluted cell concentration (cells/mL), from which 100 μL were plated (Materials and methods). Transposition efficiencies for crRNAs Tf1-835, Tf1-1165 and Tf1-control were estimated by comparing the number of formed colonies between the two plate conditions (Supplementary Data S2). The efficiency values were then normalized with that of Tf1-control as “1%”. Data are means ± SEM (n = 3 independent experiments; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by Student’s t test against Tf1-control). c Growth in liquid culture media (EMM) of LshCas13a strains with either pHL414 plasmid containing Tf1 reporter or pHL414 plasmids containing Tf1 reporter and different crRNA constructs. The strains in the assay were not treated with 5-FOA, for which Cas13a was continually activated in the presence of Tf1 transcripts and targeting crRNAs. The strains containing plasmids Tf1-835, Tf1-1165, crRNA-control or the pHL414 plasmid had an average double time of 5.1, 4.8, 4.8 and 4.7 h, respectively. Data are means ± SEM (n = 4 independent experiments).

After withdrawing thiamine from culture media to initiate Tf1 retrotransposition, the transposition frequencies for different crRNAs were estimated using the colony-forming assay in YES plates containing 5-FOA with or without G418. Compared to the normalized transposition frequency of 1.0 ± 0.033% for the control strain having the nontargeting control crRNA, the strains containing targeting crRNAs Tf1-835 or Tf1-1165, displayed reduced normalized transposition frequency of 0.84 ± 0.073% or 0.40 ± 0.089%, respectively (Fig. 5b). These values represented 16% and 60% inhibition of Tf1 retrotransposition activity, respectively, compared to that of the control strain. The varying effect of crRNAs Tf1-835 and Tf1-1165 was likely due to their different capacities for targeting Cas13a toward Tf1 RNA intermediates, as it had been shown previously that targeting efficiency for Cas13a-crRNA varied largely owing to many factors, especially the secondary structure of RNA targets that influenced crRNA binding40,47. Therefore, identifying and employing high-capacity crRNAs became critically important when applying CRISPR-Cas13 techniques to retrovirus intervention. Our results indicated that acting at RNA intermediates within the life cycle of retrovirus is a promising option for intervention by CRISPR-Cas13a.

Activation of CRISPR-Cas13a by Tf1 transcripts did not induce cell growth arrest in S. pombe

CRISPR-Cas13a was recently reported to offer immunity to bacterial hosts against phage infection by inducing growth arrest of infected hosts (termed passive protection), in addition to directly targeting invading virus40,52. The mechanism was related to the nonspecific RNase activity of activated Cas13a, which aborted the infectious cycle by stopping phage proliferation, and also to provide cross-protection for hosts against mutant escaper viruses. However, it remained an open question whether the same protection mechanism for Cas13a was involved in eukaryotic hosts.

We have shown that, in the presence of crRNAs Tf1-835 or Tf1-1165, Cas13a significantly inhibited Tf1 from retrotransposition in S. pombe. It was imperative for us to test whether cell growth arrest (or growth slowdown) took place with Cas13a activation under these conditions. To look for hint of growth arrest of S. pombe cells, we resorted to measuring their growth rates in liquid culture media. However, differently from that for measuring Tf1 retrotransposition frequency (Fig. 5b), in this assay after initiating Tf1 retrotransposition and crRNA production by withdrawing thiamine, no 5-FOA was used to remove Tf1-carrying plasmids from the cells. Thus, throughout culture and measurement, Cas13a was continuously activated in the presence of Tf1 transcripts and targeting crRNAs (Fig. 5c). As a control in the assay, constructs with no crRNA (pHL414) or a nontargeting crRNA (Tf1-control) were used to compare their growth rates. The S. pombe strains containing Tf1-targeting crRNAs, Tf1-835 or Tf1-1165, were observed to have similar growth rate with those containing pHL414 or the nontargeting crRNA (Tf1-control) (Fig. 5c). Therefore, no evidence was found for induced cell growth arrest in S. pombe cells with continued activation of Cas13a by Tf1 transcripts. We further examined the ending S. pombe populations from these liquid cultures for the presence of selection markers for Cas13a gene and Tf1/crRNA-carrying plasmid, which was validated by colony formation on selective media plates (Supplementary Fig. S9). These results indicated that, differently from that in bacterial hosts, where Cas13a activation also provided passive protection by halting the growth of infected cells, the sustained Cas13a activation by Tf1 in S. pombe did not cause cell growth arrest in the eukaryotic host. It is likely that virus-activated Cas13a acted differently in the eukaryotic cells than in bacterial hosts. This agrees with the previous observation that the nonspecific RNase activity of activated Cas13a found in bacteria was otherwise undetected in mammalian cells45. By establishing the two CRISPR systems taking advantage of two different mechanisms to intervene with retrotransposition in eukaryotic cells, we gained novel insight into the molecular actions of these CRISPR tools in combating retroviral pathogens, and explored potentially new strategies and system parameters for developing therapeutic applications in treatment of retrovirus-related diseases.

Materials and methods

Materials and general molecular biology techniques

All oligonucleotides (Supplementary Data S1) were synthesized by Genwiz Biotech (Suzhou, China). Plasmids, E. coli strains, and S. pombe strains in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables S1−5. Sanger sequencing was performed by TsingKe Biotech (Shanghai, China).

PCR was performed using KOD-FX DNA polymerase (TOYOBO) or HieffTM PCR Master MixTaq (Yeasen). DNA fragments were separated on agarose gels and were extracted using the Gel Extraction Kit (OMEGA). Plasmid DNA was extracted using the Plasmid Mini Kit I (OMEGA). Cloning construction was performed using restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs), or the ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). Reverse transcription was performed on total RNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific) and oligo (dT) primers.

The competent cells of E.coli DH5α (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were used for chemical transformations for the purpose of plasmid construction and molecular cloning. G418 (geneticin), thiamine (Vitamin B1) and 5-FOA were purchased from Abcam and TCI Development Co., Ltd. All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai, China) if not indicated otherwise.

S. pombe strains, culture and transformation

The S. pombe strain FY7652 (h-leu1-32 ura4-D18) (National BioResource Project, Osaka, Japan) was used to generate derived strains by transformation with various constructed plasmids or linear DNA (Supplementary Tables S1 and S3−S5). Yeast strains were grown in YES72 media (5 g/L yeast extract and 30 g/L glucose supplemented with 50 μg/mL uracil and/or 50 μg/mL leucine) at 32 °C either on plates or in liquid medium with 220 rpm agitation.

Yeast transformation was generally carried out with 500 ng of linearized DNA or 100 ng of circular plasmid. S. pombe cultures were first grown to mid-log phase, before cells were collected and transformed using the Lithium Acetate/PEG/Heat shock protocol72. Transformants were selected on EMM72 supplemented with 50 μg/mL uracil or 50 μg/mL leucine. Transformed colonies usually appeared on medium plates after incubation at 32 °C for 2−4 days. The pombe glutamate medium (PMG)72 (3 g/L potassium hydrogen phthalate, 2.2 g/L Na2HPO4, 3.75 g/L l-glutamic acid, monosodium salt, 20 g/L glucose, 20 mL/L of 50× salt stock, 1 mL/L of 1000× vitamin stock, 0.1 mL/L of 10,000× mineral stock) supplemented with or without thiamine (10 μM) was used to culture and prepare S. pombe strains containing Tf1 reporter vectors for Tf1 retrotransposition assay.

Construction of vectors and S. pombe strains for FnCpf1, LbCpf1 and LshCas13a expression

The codon-optimized F. novicida Cpf1 (FnCpf1) and L. bacterium Cpf1 (LbCpf1) tagged with C-terminal nuclear localization signal and 3× FLAG tag were PCR-amplified from plasmids FnCpf1-OsU6 and LbCpf1-OsU6 (gifts from Dr. Jiankang Zhu’s Lab) using the primer pair pHSN-Fn-NdeI-F and pHSN-Fn-NcoI-R (Supplementary Data S1). The plasmid pDUAL-HFF1 (RIKEN BioResource Center, Ibaraki, Japan) was digested with the NdeI/NcoI restriction enzymes, before it was assembled with the above amplified FnCpf1 or LbCpf1 PCR fragments, respectively, using ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme), producing plasmids pDUAL-HFF1-FnCpf1 and pDUAL-HFF1-LbCpf1 (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S1). The pDUAL-HFF1-Cas13a expression vectors were generated in the previous study47. For chromosomal integration of FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 expression constructs, the plasmids pDUAL-HFF1-FnCpf1 and pDUAL-HFF1-LbCpf1 were digested with the NotI restriction enzyme, and treated with FastAP Thermosensitive Alkaline Phosphatase (Thermo Scientific, Shanghai) before linearized DNA was recovered from agarose gel electrophoresis for yeast transformation. Transformants with FnCpf1, or LbCpf1 expression constructs were selected on EMM plates (supplemented with 50 μg/mL uracil), and verified for chromosomal integration by PCR with primer set ADHterm-F and leu1-R59 (Supplementary Data S1). For episomal expression of FnCpf1 in S. pombe, plasmid pDUAL-HFF1-FnCpf1 was modified by adding five crRNAs targeting MEL1 and one nontargeting crRNA to produce six plasmids (Supplementary Table S3), which were used to transform yeast cells. Transformants were selected on EMM plates (supplemented with 50 μg/mL leucine), and tested for MEL1 gene editing on agar plates containing 60 μg/mL X-α-Gal.

Measurement of growth rates for different S. pombe strains

Various S. pombe strains were first plated in EMM plates supplemented with uracil (50 μg/mL) and allowed to grow at 32 °C for several days. Colonies were picked to seed liquid cultures of 3 mL EMM (with appropriate supplements), which were grown to mid-log phase. Cells were harvested and used to inoculate 20 mL EMM (with appropriate supplements) in shake-flask culture with an initial optical density (OD600) of 0.05 (or indicated otherwise). Growth of each culture was monitored by measuring OD600 at constant intervals using Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer. The growth curves were plotted with at least four replicates of shake-flask cultures.

To detect any toxicity of FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 in S. pombe cells, the growth rates of S. pombe strains with genome-integrated FnCpf1 or LbCpf1 expression constructs were measured and compared with that of isogenic control strains (transformed with control plasmid). To determine whether activation of CRISPR-Cas13a by Tf1 transcripts induces cell growth arrest, the growth rates of LshCas13a-carrying S. pombe strains (for which LshCas13a was continually activated in the presence of Tf1 transcripts and crRNAs) in liquid culture media were measured.

Construction of Tf1 retrotransposition reporters with artificial introns

Our Tf1 retrotransposition reporter plasmids were constructed from pHL414 (a gift from Dr. Levin lab), based on the scheme from the previous study69. The plasmid pHL414 carrying Tf1 retrotransposon was modified by inserting an artificial intron sequence into the ORF of NEO gene in opposite orientation to the NEO transcript, which would align in the same orientation to that of Tf1 (Fig. 2a). Four different sites with nearby PAM sequences in the NEO gene were selected for intron insertion (Fig. 2b).

To construct the four reporters with intron, NEO fragments (~250 bp) (Supplementary Data S1) with artificial introns inserted in the above four different sites selected near PAM sequences, were first synthesized by Genwiz Biotech (Suzhou, China). These NEO fragments were PCR-amplified using the primer set Neo-TYCZ-P5 and Neo-TYCZ-P3 (Supplementary Data S1), and were inserted into linearized pHL414 (digested with EcoNI/NruI) by recombination using ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit. The series of Tf1 retrotransposition reporters with artificial introns are included in Supplementary Table S4.

Construction of crRNA vectors to direct targeting by FnCpf1, LbCpf1, and LshCas13a

Construction of crRNA expression plasmids for S. pombe was similar to those of the previous study47. Briefly, crRNA-backbone plasmids were first generated in plasmid pBluescript II KS for FnCpf1, LbCpf1, and LshCas13a, respectively (Supplementary Table S1), comprising the rrk1 promoter, direct repeat sequence (DR), BspQI placeholder for spacer sequence, and HDVR (hepatitis delta virus ribozyme)34,62. The optimized DR lengths for FnCpf1, LbCpf1, and LshCas13a are 20, 21, and 28 bp, respectively, whereas lengths for their spacer sequences are 25, 25, and 28 bp, respectively. Then, an intermediate construct (Supplementary Table S2) for each crRNA cassette was completed, using the oligonucleotide pairs designed for spacer of each crRNA (Supplementary Data S1). The oligonucleotide pairs were first annealed to form stick-end, before being cloned into the BspQI placeholder.

For generation of FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 crRNAs to target the endogenous MEL1 gene, the corresponding intermediate constructs were used as templates to PCR-amplify the crRNA cassettes (comprising rrk1 promoter, DR, spacer and HDVR), using the primer set pDUAL-SpeI-T3 and pDUAL-PspXI-T7 (Supplementary Data S1). The crRNA cassette PCR fragments were then inserted into linearized plasmids pDUAL-HFF1 (digested with SpeI/XhoI) by recombination using ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). As for crRNAs for episomal expression of FnCpf1, the crRNA cassette fragments were inserted into the FnCpf1 expression plasmid pDUAL-HFF1-FnCpf1, instead of pDUAL-HFF1 (Supplementary Table S3).

For generation of FnCpf1 crRNAs to target the four NEO sequences (generated via splicing) within Tf1 DNA intermediates (Fig. 2b), the corresponding intermediate constructs were used as templates to PCR-amplify the crRNA cassettes, using the primer set pHL414-NheI-T7 and pHL414-NheI-T3 (Supplementary Data S1). The crRNA cassette PCR fragments were then inserted into linearized plasmids of Tf1 retrotransposition reporters (digested with NheI) to form nine crRNA vectors (Supplementary Table S4), by recombination using ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme), respectively.

For generation of genome-integrated FnCpf1 crRNA constructs to target the four NEO sequences (generated via splicing) within Tf1 DNA intermediates (Fig. 2b), the corresponding intermediate constructs were used as templates to PCR-amplify the crRNA cassettes, using the primer set pDUAL-SpeI-SK and pDUAL-SpeI-T3 (Supplementary Data S1). The crRNA cassette PCR fragments were then inserted into linearized FnCpf1 expression plasmid, pDUAL-HFF1-FnCpf1 (digested with SpeI) to form six crRNA vectors (Supplementary Table S4), by recombination using ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme). The resulting six plasmids (five targeting crRNA and one nontargeting control) were linearized by NotI digestion for yeast transformation to create six different genome-integrated crRNA construct strains.

For generation of LshCas13a crRNAs to target Tf1 RNA intermediates, the corresponding intermediate constructs were used as templates to PCR-amplify the crRNA cassettes, using the primer set NheI-TYB-P5 and NheI-TYB-P3 (Supplementary Data S1). The crRNA cassette PCR fragments were then inserted into linearized plasmid pHL414 carrying Tf1 retrotransposon (digested with NheI) to form three crRNA vectors (Supplementary Table S5), by recombination using ClonExpress® II One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme).

In above crRNA constructs, a nontargeting crRNA was designed and constructed as Cas12a and Cas13a targeting controls, respectively. For Cas12a, the nontargeting spacer sequence was “AACAGCGCCTTAAAAGAACTAGAAA”. For Cas13a, the nontargeting spacer sequence was “CAGACTATGCGTCGACAAGCCAGGCATT”. All constructed plasmids were validated by diagnostic PCR and Sanger sequencing.

Assay for Tf1 retrotransposition in S. pombe

To qualitatively determine the Tf1 retrotransposition, the “transfer-and-patch” assay was performed following the previously developed protocol47,69. In brief, various S. pombe strains were first plated in EMM plates supplemented with thiamine (10 μM) and were grown for 4 days at 32 °C. Then individual colonies were picked with sterile toothpicks and transferred on PMG plates with thiamine (10 μM) for patch growth. After incubation at 32 °C for 3 days, the patches were transferred to PMG plates (without thiamine to initiate transcription and retrotransposition), and allowed to grow for 4 days. The patches were transferred to PMG plates containing 5-FOA, uracil and thiamine, and allowed to grow for 3 days before patches were transferred to YES plates containing 5-FOA, uracil and G418.

To quantitatively measure Tf1 retrotransposition frequency, the colony-forming assay was performed following the previously developed protocol47,69. In brief, various S. pombe strains were first plated on EMM plates supplemented with thiamine (10 μM) and were grown for 4 days at 32 °C. Then individual colonies were picked and transferred on PMG plates with thiamine (10 μM) for patch growth. After incubation at 32 °C for 3 days, the patches were transferred to liquid PMG medium (without thiamine to initiate transcription and retrotransposition) at OD600 of 0.05. The cultures were allowed to grow at 32 °C for another 4 days before being treated in liquid PMG containing 5-FOA (1 mg/mL) and uracil (50 μg/mL) for 36 h. The cultures were used subsequently to make serial dilutions for 107, 106 and 105 cells/mL, and 100 μL of them were plated onto paired YES plates containing either 5-FOA or both 5-FOA and G418. Plated cells were allowed to grow for 2−3 days, and the numbers of colonies formed on paired plates were counted, for which frequencies of Tf1 retrotransposition were estimated by comparing the colony numbers from paired plates with both G418 and 5-FOA, or with 5-FOA only.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Henry Levin for plasmids containing retrotransposon Tf1, and Dr. Jiankang Zhu for plasmids containing FnCpf1 and LbCpf1 genes. This study was supported in part by the National Science and Technology Major Projects (2018YFC0310600), the Strategic Projects of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA24010400, ZSYS-014), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31771412, 31972881).

Author contributions

P.H. conceived the project and directed the study. N.Z. and X.J. performed experiments, analyzed data and prepared the manuscript. Y.L., M.C., X.Z. and J.J. helped with experiments and data analysis. X.L. and H.W. advised on the study and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Niubing Zhang, Xinyun Jing

Contributor Information

Xuan Li, Email: lixuan@sippe.ac.cn.

Pei Hao, Email: phao@ips.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper at (10.1038/s41421-020-0164-0).

References

- 1.Barrangou R, Marraffini LA. CRISPR-Cas systems: prokaryotes upgrade to adaptive immunity. Mol. Cell. 2014;54:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marraffini LA. CRISPR-Cas immunity in prokaryotes. Nature. 2015;526:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature15386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuong EB, Elde NC, Feschotte C. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: from conflicts to benefits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017;18:71–86. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klug A. The discovery of zinc fingers and their applications in gene regulation and genome manipulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:213–231. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-010909-095056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liang C, Wainberg MA, Das AT, Berkhout B. CRISPR/Cas9: a double-edged sword when used to combat HIV infection. Retrovirology. 2016;13:37–37. doi: 10.1186/s12977-016-0270-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwarteng A, Ahuno ST, Kwakye-Nuako G. The therapeutic landscape of HIV-1 via genome editing. AIDS Res. Ther. 2017;14:32–32. doi: 10.1186/s12981-017-0157-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, et al. Evaluation of a combinatorial RNAi lentivirus vector targeting foot-and-mouth disease virus in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015;12:6672–6678. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergallo M, et al. CMV induces HERV-K and HERV-W expression in kidney transplant recipients. J. Clin. Virol. 2015;68:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuyl ACVD. HIV infection and HERV expression: a review. Retrovirology. 2012;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown J, Matthews AL, Sandstrom PA, Chapman LE. Xenotransplantation and the risk of retroviral zoonosis. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:411–415. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(98)01347-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yann M, Yannick B, Hélène F, André J. Porcine endogenous retrovirus integration sites in the human genome: features in common with those of murine leukemia virus. J. Virol. 2006;80:10980–10988. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00904-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss RA. How does HIV cause AIDS? Science. 1993;260:1273–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.8493571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo RC. A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years. Retrovirology. 2006;3:72. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gougeon ML. Alarmins and central nervous system inflammation in HIV-associated neurological disorders. J. Intern. Med. 2016;281:433–447. doi: 10.1111/joim.12570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nightingale S, et al. Controversies in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quaresma JAS, et al. HTLV-1, immune response and autoimmunity. Viruses. 2016;8:5. doi: 10.3390/v8010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downey RF, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus K and cancer: innocent bystander or tumorigenic accomplice? Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:1249–1257. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakagawa K. The potential roles of endogenous retroviruses in autoimmunity. Immunol. Rev. 2010;152:193–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.1996.tb00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaminski R, et al. Negative feedback regulation of HIV-1 by gene editing strategy. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31527. doi: 10.1038/srep31527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu W, et al. RNA-directed gene editing specifically eradicates latent and prevents new HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:11461–11466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405186111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G, Zhao N, Berkhout B, Das AT. A combinatorial CRISPR-Cas9 attack on HIV-1 DNA extinguishes all infectious provirus in infected T cell cultures. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2819–2826. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fuentes DR, Swigut T, Wysocka J. Systematic perturbation of retroviral LTRs reveals widespread long-range effects on human gene regulation. eLife. 2018;7:e35989. doi: 10.7554/eLife.35989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niu D, Wei HJ. Inactivation of porcine endogenous retrovirus in pigs using CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2017;357:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saika H, Mori A, Endo M, Toki S. Targeted deletion of rice retrotransposon Tos17 via CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;38:455–458. doi: 10.1007/s00299-018-2357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zetsche B, et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163:759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinstiver BP, et al. Genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas Cpf1 nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:869–874. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hui KK, et al. In vivo high-throughput profiling of CRISPR–Cpf1 activity. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:153–159. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stella S, Alcón P, Montoya G. Class 2 CRISPR-Cas RNA-guided endonucleases: Swiss Army knives of genome editing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:882–892. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swiat MA, et al. FnCpf1: a novel and efficient genome editing tool for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:12585–12598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamano T, et al. Structural basis for the canonical and non-canonical PAM recognition by CRISPR-Cpf1. Mol. Cell. 2017;67:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonfara I, Richter H, Bratovič M, Le RA, Charpentier E. The CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA. Nature. 2016;532:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zetsche B, et al. Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:31–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhong G, Wang H, Li Y, Mai HT, Farzan M. Cpf1 proteins excise CRISPR RNAs from mRNA transcripts in mammalian cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13:839–841. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Mao Y, Lu Y, Tao X, Zhu JK. Multiplex gene editing in rice using the CRISPR-Cpf1 system. Mol. Plant. 2017;10:1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fagerlund RD, Staals RHJ, Fineran PC. The Cpf1 CRISPR-Cas protein expands genome-editing tools. Genome Biol. 2015;16:251. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0824-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Le C, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li B, et al. Engineering CRISPR–Cpf1 crRNAs and mRNAs to maximize genome editing efficiency. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017;1:0066. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim D, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016;34:863–868. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abudayyeh OO, et al. C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science. 2016;353:aaf5573. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eastseletsky A, et al. Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature. 2016;538:270–273. doi: 10.1038/nature19802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knott GJ, et al. Guide-bound structures of an RNA-targeting A-cleaving CRISPR-Cas13a enzyme. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2017;24:825–833. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smargon AA, et al. Cas13b is a type VI-B CRISPR-associated RNA-guided RNase differentially regulated by accessory proteins Csx27 and Csx28. Mol. Cell. 2017;65:618–630. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gootenberg JS, et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science. 2017;356:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abudayyeh OO, et al. RNA targeting with CRISPR-Cas13. Nature. 2017;550:280–284. doi: 10.1038/nature24049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dbt C, et al. RNA editing with CRISPR-Cas13. Science. 2017;358:1019–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jing X, et al. Implementation of the CRISPR-Cas13a system in fission yeast and its repurposing for precise RNA editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:90. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Aman R, et al. RNA virus interference via CRISPR/Cas13a system in plants. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1381-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aman R, Mahas A, Butt H, Aljedaani F, Mahfouz M. Engineering RNA virus interference via the CRISPR/Cas13 machinery in Arabidopsis. Viruses. 2018;10:732. doi: 10.3390/v10120732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhan X, et al. Generation of virus-resistant potato plants by RNA genome targeting. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:1814–1822. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang T, et al. Establishing CRISPR/Cas13a immune system conferring RNA virus resistance in both dicot and monocot plants. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2019;17:1185–1187. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meeske AJ, Nakandakari-Higa S, Marraffini LA. Cas13-induced cellular dormancy prevents the rise of CRISPR-resistant bacteriophage. Nature. 2019;570:241–245. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1257-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Havecker ER, Gao X, Voytas DF. The diversity of LTR retrotransposons. Genome Biol. 2004;5:225–225. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-6-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garcia-Pérez, J. L. Transposons and Retrotransposons (Humana Press, 2016).

- 55.Wicker T, et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007;8:973–982. doi: 10.1038/nrg2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mccarthy EM, Mcdonald JF. Long terminal repeat retrotransposons of Mus musculus. Genome Biol. 2004;5:14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haag AL, Lin JH, Levin HL. Evidence for the packaging of multiple copies of Tf1 mRNA into particles and the trans priming of reverse transcription. J. Virol. 2000;74:7164–7170. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.15.7164-7170.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levin HL, Weaver DC, Boeke JD. Novel gene expression mechanism in a fission yeast retroelement: Tf1 proteins are derived from a single primary translation product. EMBO J. 1993;12:4885–4895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matsuyama A, Yoshida M. Heterologous gene expression by chromosomal integration in fission yeast. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;824:433–450. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-433-9_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rupp S. LacZ assays in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:112–131. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)50959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pokharel S, Beal PA. High-throughput screening for functional adenosine to inosine RNA editing systems. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006;1:761–765. doi: 10.1021/cb6003838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobs JZ, Ciccaglione KM, Tournier V, Zaratiegui M. Implementation of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in fission yeast. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5344. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Au V, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 methodology for the generation of knockout deletions in Caenorhabditis elegans. G3. 2019;9:135–144. doi: 10.1534/g3.118.200778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu Y, et al. Recombinant expression of truncated exonuclease VIII and its application in in vitro DNA recombination. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2019;35:827–836. doi: 10.13345/j.cjb.180496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kunitake E, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene replacement in the basidiomycetous yeast Pseudozyma antarctica. Fungal Genet Biol. 2019;130:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsuyama A, et al. pDUAL, a multipurpose, multicopy vector capable of chromosomal integration in fission yeast. Yeast. 2004;21:1289–1305. doi: 10.1002/yea.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuen G, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout is insensitive to target copy number but is dependent on guide RNA potency and Cas9/sgRNA threshold expression level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:12039–12053. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen S, Lee B, Lee AY, Modzelewski AJ, He L. Highly efficient mouse genome editing by CRISPR ribonucleoprotein electroporation of Zygotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:14457–14467. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.733154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sangesland M, Atwood-Moore A, Rai SK, Levin HL. Qualitative and quantitative assays of transposition and homologous recombination of the retrotransposon Tf1 in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1400:117–130. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3372-3_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen JS, et al. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science. 2018;360:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Levin HL, Boeke JD. Demonstration of retrotransposition of the Tf1 element in fission yeast. EMBO J. 1992;11:1145–1153. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05155.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sabatinos SA, Forsburg SL. Molecular genetics of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:759–795. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70032-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.