Abstract

Homeostatic plasticity refers to the ability of neuronal networks to stabilize their activity in the face of external perturbations. Most forms of homeostatic plasticity ultimately depend on changes in the expression or activity of ion channels and synaptic proteins, which may occur at the gene, transcript, or protein level. The most extensively investigated homeostatic mechanisms entail adaptations in protein function or localization following activity-dependent posttranslational modifications. Numerous studies have also highlighted how homeostatic plasticity can be achieved by adjusting local protein translation at synapses or transcription of specific genes in the nucleus. In comparison, little attention has been devoted to whether and how alternative splicing (AS) of pre-mRNAs underlies some forms of homeostatic plasticity. AS not only expands proteome diversity but also contributes to the spatiotemporal dynamics of mRNA transcripts. Prominent in the brain where it can be regulated by neuronal activity, it is a flexible process, tightly controlled by a multitude of factors. Given its extensive use and versatility in optimizing the function of ion channels and synaptic proteins, we argue that AS is ideally suited to achieve homeostatic control of neuronal output. We support this thesis by reviewing emerging evidence linking AS to various forms of homeostatic plasticity: homeostatic intrinsic plasticity, synaptic scaling, and presynaptic homeostatic plasticity. Further, we highlight the relevance of this connection for brain pathologies.

Keywords: alternative splicing, homeostatic plasticity, repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor (REST), homer1, P/Q-type Ca2+ channels

Introduction: From Genes to Function

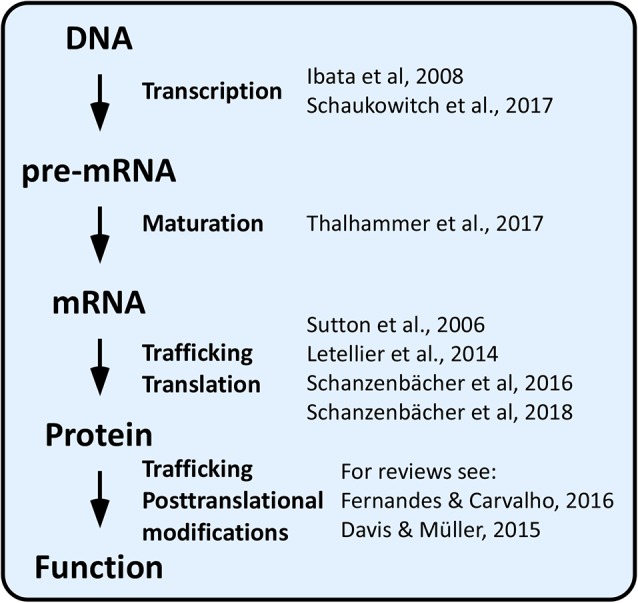

Over the last two decades, a vast array of homeostatic plasticity adaptations, which enable neuronal networks to stabilize their activity in the face of external perturbations, have been identified. These involve adjustments in synaptic strength by means of pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms (homeostatic synaptic plasticity) and in intrinsic excitability (homeostatic intrinsic plasticity). Ultimately, both synaptic and intrinsic forms of homeostatic plasticity depend on changes in expression or activity of ion channels and synaptic proteins, which may occur at the gene, transcript, or protein level (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Genes to function in homeostatic plasticity.

By far, the most extensively investigated homeostatic mechanisms involve changes in protein function or localization by means of posttranslational modifications affecting protein–protein interactions and trafficking (reviewed in Turrigiano, 2011; Davis and Müller, 2015; Fernandes and Carvalho, 2016; Cingolani et al., 2019).

Chronic changes in network activity can also be counteracted by regulating protein translation. For example, increased surface expression of the GluA1 subunit of AMPA-type glutamate receptors (AMPARs) compensates blockade of network activity within a few hours. This form of homeostatic synaptic plasticity, known as synaptic upscaling, requires local protein synthesis because it is prevented by dendritic application of the protein synthesis inhibitors anisomycin or emetine (Sutton et al., 2006), and it involves downregulation of miR92a (Letellier et al., 2014; Dubes et al., 2019). Further, the transcription of hundreds of genes was recently shown to be up- or downregulated at early (2 h) and late (24 h) stages of the homeostatic response (Schanzenbächer et al., 2016, 2018).

Synaptic upscaling following tetrodotoxin (TTX)-induced suppression of network activity is dependent also on gene transcription because the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D (ActD) blocks effectively upscaling of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and dendritic accumulation of the AMPAR subunit GluA2 (Ibata et al., 2008). More recently, chronic suppression of network activity was shown to alter the transcription of tens of genes, including that for the AMPAR clustering protein neuronal pentraxin-1 (Nptx1); Ca2+ entry via T-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs) appears essential for this signaling pathway (Schaukowitch et al., 2017). Conversely, chronic augmentation of network activity leads to Ca2+-dependent changes in the expression of hundreds of genes (Flavell and Greenberg, 2008; Schaukowitch et al., 2017), some of which, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), calcineurin, and MeCP2, are known players in homeostatic synaptic plasticity (Fernandes and Carvalho, 2016). Neuronal activity also increases the expression levels of immediate early genes, such as Arc (aka Arg3.1), which induces a counterbalancing internalization of AMPARs (Shepherd et al., 2006) and, when localized in the nucleus, decreases transcription of the AMPAR subunit GluA1, thereby reducing synaptic strength (Korb et al., 2013).

In comparison to the above outlined molecular mechanisms, little attention has thus far been devoted to whether and how homeostatic adaptations are achieved at the level of alternative splicing (AS) of pre-mRNAs (Figure 1). As detailed below, this lack of attention may come as a surprise because some AS events are well-known for being controlled by neuronal activity and because AS is ideally suited to optimize protein function to new challenges (Raj and Blencowe, 2015; Vuong et al., 2016; Baralle and Giudice, 2017). Here, we review recent findings linking homeostatic plasticity to AS and discuss the relevance of activity-dependent AS to achieve homeostatic control of neuronal output in health and diseased states.

Alternative Splicing

During RNA maturation, intervening noncoding RNA sequences (introns) are removed while coding sequences (exons) are joined together, thus contributing to transforming a newly transcribed mRNA (pre-mRNA) into a mature mRNA. RNA splicing is performed by a multi-molecular RNA–protein complex, the spliceosome, which binds to specific sequences on the pre-mRNA. These include a donor site (5′ end of the excised intron), an acceptor site (3′ end of the intron), and, upstream of the 3′ site, a polypyrimidine tract and a branch point. For some genes, rather than being univocal, the splicing process creates a range of mature mRNAs, each with a unique exon composition. If translated, these mRNA splice isoforms will produce multiple protein variants with potentially distinct functions. We talk in this case of AS. AS is regulated by cis-acting elements (regulatory RNA sequences), which act as splicing enhancers or repressors by recruiting trans-acting splicing factors (proteins or ribonucleoproteins) that favor or inhibit different steps of the splicing reaction (Matera and Wang, 2014).

In higher eukaryotes, AS has the potential to convert a limited number of genes into an astounding variety of proteins depending on developmental stage, brain region, and cell types. For example, thousands of mRNA splicing isoforms were found to be different between neurons and glial cells when comparing purified brain cell populations (Zhang et al., 2014). Indeed, some splicing factors display cell-type specific expression (Nguyen et al., 2016; Furlanis and Scheiffele, 2018), while others regulate specific splicing events during brain development (Norris and Calarco, 2012). Transcriptomic and proteomic studies indicate that more than 90% of mammalian genes undergo AS, with the brain exhibiting the most complex repertoire of splice variants (Pan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2014; Schreiner et al., 2015). In some cases, as for neurexins and calcium channels, one single gene can give rise to potentially thousands of different mRNA isoforms (Ullrich et al., 1995; Soong et al., 2002; Lipscombe et al., 2013; Schreiner et al., 2014; Treutlein et al., 2014), many of which have been identified at the protein level (Kim et al., 2014; Schreiner et al., 2015). It should also be noted that AS is not limited to diversifying the coding sequence of an mRNA but can also modify the selection of 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs), thus affecting stability, subcellular localization and translation of mRNAs (Hermey et al., 2017; Mauger and Scheiffele, 2017).

In order to be instructive for homeostatic plasticity, AS needs to fulfill two criteria: (i) it must be regulated by neuronal activity; and (ii) the outcome of the splicing process must result in a homeostatic compensation. We will explore the requirement of AS in homeostatic plasticity in the next paragraphs following three exemplary cases.

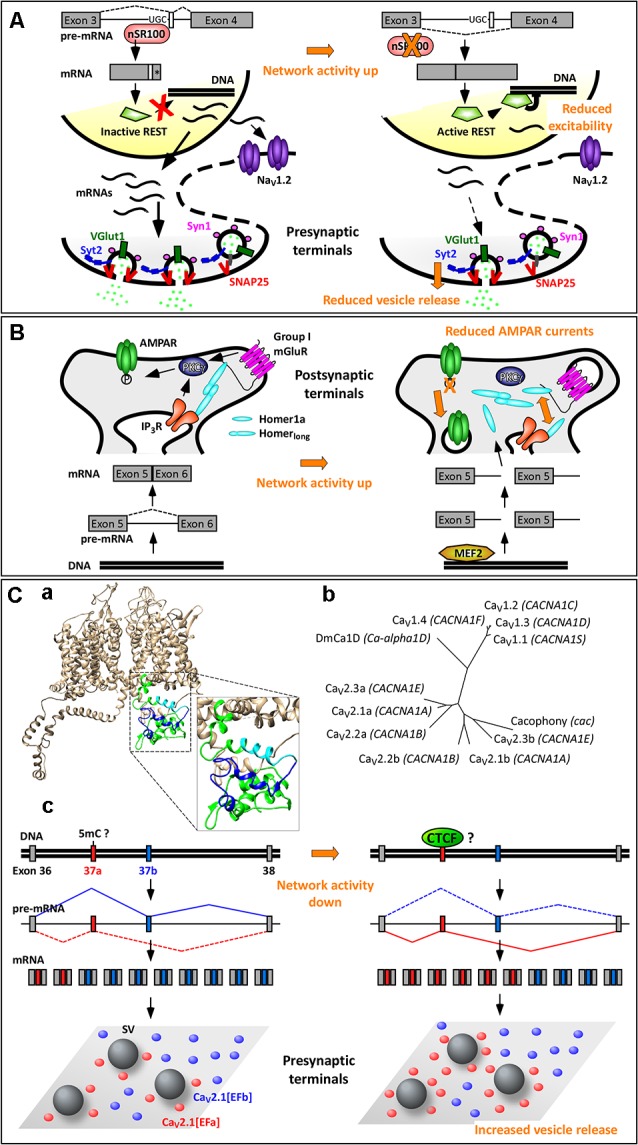

NSR100, Microexons, and Rest in Homeostatic Plasticity

Some splicing factors, such as Nova-1/2, Rbfox-1/2/3, Ptbp1/2, and nSR100 are highly enriched in neurons. Among these, the Ser/Arg repeat-related protein of 100 kDa (nSR100, aka SRRM4) binds to intronic enhancer UGC elements close to the 3’ splice sites to promote microexon inclusion (Figure 2A; Raj and Blencowe, 2015). Microexons are a class of cassette exons (exons that can be included or not in the mature transcript) that tend to be located in surface loops and intrinsically disordered regions. They generally have a length of 9–21 nucleotides (nt), often in multiples of three nt, hence leading to alternative versions of a protein with altered functions, protein–protein interaction motifs, or posttranslational modifications. Microexons are especially important in the brain, where they constitute nearly one third of all neural-regulated splicing events. They are frequently misregulated in the brain of individuals with autism spectrum disorder; this is likely due to increased neuronal activity, often associated with autism spectrum disorder, resulting in a rapid decrease in nSR100 expression and increased skipping of microexons (Irimia et al., 2014; Quesnel-Vallières et al., 2016).

Figure 2.

Activity-dependent alternative splicing in homeostatic plasticity. (A) A chronic increase in neuronal activity downregulates the expression of the splicing factor nSR100, with consequent skipping of a 16-nt-long microexon in the pre-mRNA of the transcriptional repressor REST (repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor). The resulting REST protein is active and reduces the expression of NaV1.2 and of presynaptic proteins. These two effects contribute to homeostatic intrinsic plasticity and presynaptic homeostatic plasticity, respectively. (*) Indicates a STOP codon. (B) The selective induction of the short isoform Homer1a upon increase in neuronal activity is mediated by the transcription factor myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2), which promotes expression of the Homer1 gene, and by a concomitant termination of transcription between exons 5 and 6. Homer1a outcompetes the longer isoforms of Homer1, resulting in dispersion of group 1 mGluRs and dephosphorylation of AMPARs. This contributes to synaptic downscaling. (C) Mutually exclusive splicing of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in presynaptic homeostatic plasticity. (Ca) Structural model of human CaV2.1[EFb] (UniProt ID: O00555; Martinez-Ortiz and Cardozo, 2018), highlighting the full C-terminus (green, cyan, blue), the part of the EF-hand-like domain shared between CaV2.1[EFa] and CaV2.1[EFb] (E helix; cyan) and the sequence specific to CaV2.1[EFb] (loop, F helix and downstream residues; blue). (Cb) Phylogenetic tree of human CaV1 and CaV2 channels and of Cacophony and DmCa1D from Drosophila melanogaster for the amino acidic region corresponding to exons 37 of CaV2.1 (Clustal Omega www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/, rendering using TreeDyb, http://www.phylogeny.fr/one_task.cgi?tasktype=treedyn, Chevenet et al., 2006); UniProt IDs: CaV1.1: Q13698, aa: 1414–1446; CaV1.2: Q13936, aa: 1587–1589; CaV1.3: Q01668, aa: 1497–1529; CaV1.4: O60840, aa: 1474–1506; CaV2.1b: O00555, aa: 1843–1875; CaV2.2b: Q00975, aa: 1741–1773; CaV2.3b: Q15878, aa: 1756–1788; CaV2.1a: O00555-4, aa: 1844–1876; Cacophony: P1645, aa: 1370–1402; DmCa1D: Q24270, aa: 1959–1991; sequences for CaV2.2a and CaV2.3a are as in Thalhammer et al. (2017). The three exons 37a cluster together as do the three exons 37b, suggesting conservation of these mutually exclusive exons across CaV2 channels; the corresponding region of Cacophony from D. melanogaster is more tightly related to exon 37b. (Cc) The increased expression of the isoform CaV2.1[EFa] upon chronic activity deprivation might occur following demethylation of the exon 37a locus with consequent binding of the chromatin organizer CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) to it. CaV2.1[EFa] localizes in close proximity to fuse-competent synaptic vesicles, thereby supporting effectively vesicle release and presynaptic homeostatic plasticity. Drawing of relative exon/intron length is to scale only in (Cc); numbers of mRNAs and proteins are not intended to be quantitative.

Although generally frame preserving, microexon inclusion promoted by nSR100 can also disrupt the reading frame of a gene. For example, one well-known downstream target of nSR100 is the transcriptional repressor REST (repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor; aka NRSF, neural restrictive silencing factor), which silences a multitude of neural genes (Raj et al., 2011). In this case, nSR100 promotes the inclusion of a 16-nt-long microexon located between the third and fourth exons, leading to a frameshift introducing a stop codon at the beginning of the fourth exon. The resulting isoform, REST4, is truncated and lacks the domains required for transcriptional repression of target genes (Raj et al., 2011). When neuronal activity increases, nSR100 expression is rapidly downregulated (Quesnel-Vallières et al., 2016), resulting in skipping of the 16-nt-long microexon and production of the active isoform of REST (Figure 2A). Accordingly, REST is upregulated in primary neuronal cultures after 48–96 h of network hyperactivity, and this decreases the expression of its targets, including the sodium channel NaV1.2, the calcium channel CaV3.2, and various presynaptic proteins (SNAP-25, Synapsin-1, Synaptotagmin-2, and vGlut-1; van Loo et al., 2012; Pozzi et al., 2013). Downregulation of NaV1.2 makes it more difficult for a neuron to elicit action potentials, thus contributing to homeostatic intrinsic plasticity (Pozzi et al., 2013). Decreased expression of presynaptic proteins correlates with a reduction in the number of docked synaptic vesicles and in the frequency of mEPSCs, thus contributing to presynaptic homeostatic plasticity, a prominent form of homeostatic synaptic plasticity (Figure 2A; Pecoraro-Bisogni et al., 2018).

Alternative Splice Isoforms of HOMER1 in Synaptic Scaling

The Homer1 gene generates long and short splice isoforms. The major isoforms, Homer1b, Homer1c, and Homer1d, are long, constitutively expressed, and act as scaffold proteins at postsynaptic sites (Fagni et al., 2002; Shiraishi-Yamaguchi and Furuichi, 2007). In response to various stimuli, such as electroconvulsive seizures, cocaine, kainate or nicotine exposure, two truncated isoforms of Homer1, Homer1a and Ania3, which have all the characteristics of immediate early gene products, are rapidly (1–4 h) induced (Brakeman et al., 1997; Kato et al., 1997; Berke et al., 1998; Bottai et al., 2002). This is due to myocyte enhancer factor 2 (MEF2) family transcription factors, which boost transcription of the Homer1 gene and to a concomitant termination of transcription within the large central intron between exons 5 and 6, leading to use of alternative poly(A) sites. Because of this coordinated increase in transcription rate and premature transcription termination, only the short isoforms of Homer1 are induced by neuronal activity (Figure 2B; Bottai et al., 2002; Flavell et al., 2008).

The long isoforms of Homer1 consist of two major domains: (i) an N-terminal Enabled/Vasp homology 1 (EVH1) domain, which binds to proline-rich sequences in Group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR1 and 5), inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) receptors, ryanodine receptors, TRPC1 ion channels, and the scaffold protein Shank; and (ii) a C-terminal coiled-coil (CC) structure followed by leucine zipper motifs, which favor oligomerization of homer proteins (Szumlinski et al., 2006). The long isoforms of Homer1 are therefore essential in cross-linking multiple postsynaptic proteins. Conversely, the short isoforms of Homer1 lack the C-terminal domain involved in oligomerization; once induced, they act as dominant-negative regulators disrupting the binding between Homer1 long isoforms and their effectors (Xiao et al., 1998; Kammermeier and Worley, 2007).

Increasing network activity, therefore, upregulates transiently the expression of Homer1a, which, among other things, disrupts the protein–protein interactions clustering group 1 mGluRs at perisynaptic sites. In addition, Homer1a acts as an endogenous allosteric modulator of mGluR1/5; that is, it supports a glutamate-independent activity of these mGluRs (Ango et al., 2001). This is essential in promoting homeostatic downscaling of synaptic AMPARs both in vitro and in vivo (Figure 2B; Hu et al., 2010; Diering et al., 2017), as reviewed elsewhere in this topic (Cingolani et al., 2019).

The expression of Homer1a is increased in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in schizophrenic patients (Matosin et al., 2016) and up- or downregulated in different brain regions of patients with either bipolar disorder or major depression (Leber et al., 2017). Furthermore, in Fmr1 knockout mice, a model for fragile X syndrome, mGluR5 is preferentially associated to Homer1a, leading to an enhanced glutamate-independent activation of this receptor and consequent neocortical circuit dysfunctions and behavioral abnormalities. Some of these defects are rescued by genetic deletion of Homer1a (Giuffrida et al., 2005; Ronesi et al., 2012), which is consistent with brain function being dependent on an appropriate ratio between short and long isoforms of Homer1.

Alternative Splicing of P/Q-Type Ca2+ Channels in Presynaptic Homeostatic Plasticity

Mutually exclusive splicing is a form of AS, whereby the splicing of two or more exons is coordinated in such a way that only one is retained while the others are spliced out from the mature mRNA (Figure 2Cc). Mutually exclusive exons are generally highly similar possibly because they originated from exon duplication. However, far from being redundant, they usually allow the formation of protein isoforms that differ in the function of specific domains while preserving the overall structure and size. Indeed, mutually exclusive splicing in many genes is spatially and temporally regulated (Pohl et al., 2013). Recent data indicate that mutually exclusive exons may be much more frequent in mammals than previously thought and that they are overrepresented in genes encoding for ion channels (Hatje et al., 2017). Interestingly, the occurrence of pathogenic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in mutually exclusive and cassette exons is significantly higher than in other types of exons, suggesting that these two forms of AS are especially susceptible to pathogenic mutations. For mutually exclusive splicing, the pathogenic SNPs tend to be present in only one of the two possible exons. Thus, the second mutually exclusive exon cannot normally replace the defective one either because of functional diversification or because of differential spatiotemporal expression patterns (Hatje et al., 2017).

A well-characterized case of mutually exclusive exons occurs in the proximal C-terminus of the pore-forming α1 subunit of the CaV2 VGCCs (CaV2.1, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3; Bourinet et al., 1999; Bell et al., 2004; Gray et al., 2007; Hatje et al., 2017), which serve as primary Ca2+ entry for the release of synaptic vesicles at most presynaptic terminals. The 97-nt-long mutually exclusive exons 37a and 37b encode part of an EF-hand-like domain, thus creating two variants of it (EFa and EFb; Figure 2Ca; Bourinet et al., 1999; Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Thalhammer et al., 2017). This motif is not specific to CaV2 channels but conserved across Ca2+ and Na+ channels (Babitch, 1990; Ben-Johny et al., 2014); in particular, exons 37a and 37b in CaV2 channels exhibit a high level of similarity with the corresponding exons in CaV1 channels (Figure 2Cb).

Which are the functions of the EF-hand-like domain and why do CaV2 channels need two variants of it? Three major, not mutually exclusive, functional differences have been proposed. In N-type Ca2+ channels (CaV2.2), mutually exclusive splicing at exons 37 has been shown to regulate sensitivity of the channel to voltage-independent inhibition by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). That is, several GPCRs, including opioid receptors, inhibit CaV2.2[EFa] but not CaV2.2[EFb] through kinase phosphorylation of a tyrosine residue (Y1743) present exclusively in the former isoform (Raingo et al., 2007; Andrade et al., 2010). Because CaV2.2[EFa] is enriched in capsaicin-responsive nociceptors of dorsal root ganglia (Bell et al., 2004), this isoform-specific regulation mediates analgesia, for example, by morphine (Andrade et al., 2010).

In P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (CaV2.1), the two isoforms have been shown to differ in how elevations in intracellular Ca2+ regulate the activity of the channel. Specifically, activation of CaV2.1[EFa], but not CaV2.1[EFb], is facilitated by preceding Ca2+ entry (Ca2+-dependent facilitation, CDF; Chaudhuri et al., 2004). This is in accordance with a large body of evidence indicating that the EF-hand-like domain in the proximal C-terminus of Ca2+ and Na+ channels, rather than binding directly to Ca2+, represents a general transduction element for the regulation of the channel by Ca2+-calmodulin (Peterson et al., 2000; Ben-Johny et al., 2014; Gardill et al., 2018). Calmodulin itself binds, in a Ca2+-independent manner, to downstream domains in the C-terminus of Ca2+ and Na+ channels (Peterson et al., 1999; Zuhlke et al., 1999; Mori et al., 2000; Erickson et al., 2001).

More recently, experiments in native systems have revealed that the two isoforms of CaV2.1 regulate neurotransmitter release and short-term synaptic plasticity at hippocampal synapses in opposite directions. While CaV2.1[EFa] promotes synaptic efficacy and short-term synaptic depression, CaV2.1[EFb] characterizes synapses with low release probability and prominent short-term synaptic facilitation (Thalhammer et al., 2017). This is contrary to what the isoform-specific CDF, as characterized in non-neuronal cells, would have predicted (Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Weyrer et al., 2019); it likely reflects instead a differential spatial relationship of the two isoforms to fuse-competent synaptic vesicles, with a tight and loose coupling configuration for CaV2.1[EFa] and CaV2.1[EFb], respectively (Figure 2Cc; Thalhammer et al., 2017). More in general, AS of CaV2.1 might underlie most of the intra- and inter-synaptic differences in nanoscale topographical arrangements of this channel, as recently revealed (Holderith et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2015; Rebola et al., 2019).

Whereas the expression of CaV2.1[EFb] remains relatively constant throughout postnatal development, that of CaV2.1[EFa] increases postnatally, in parallel with a tightening of the coupling between VGCCs and the neurotransmitter release machinery. As a result, both isoforms are expressed at similar levels in most regions of the adult brain (Bourinet et al., 1999; Soong et al., 2002; Vigues et al., 2002; Chaudhuri et al., 2004; Thalhammer et al., 2017). The developmental upregulation of CaV2.1[EFa] occurs in rodents between the second and third postnatal week, the same period when ataxic symptoms become apparent in CaV2.1−/− knockout mice (Mark et al., 2011). Further, four point mutations associated with episodic ataxia type II have been identified in the exon 37a of CACNA1A (the gene for the α1 subunit of CaV2.1) in four unrelated families (Graves et al., 2008; Mantuano et al., 2010), while none has been found, to date, in exon 37b, suggesting that CaV2.1[EFa] might be more relevant for the etiology of episodic ataxia type II than CaV2.1[EFb].

At the cellular level, while most neurons express both isoforms to various degrees, parvalbumin interneurons, which rely on P/Q-type Ca2+ channels to form synapses characterized by nanodomain coupling, high release probability, and short-term synaptic depression (Eggermann et al., 2012), stand out for expressing exclusively CaV2.1[EFa] (Huntley et al., 2020), again pointing to functional synaptic specialization of the two CaV2.1 splice isoforms.

Besides these differences in spatiotemporal expression patterns, the relative synaptic abundance of the two isoforms is regulated by network activity in a homeostatic fashion. Specifically, hippocampal neurons increase exclusively the synaptic expression of CaV2.1[EFa] in response to activity deprivation. Because this isoform is the more efficient of the two in driving vesicle release, its higher expression levels appear perfectly suited to counteract the decrease in network activity (Figure 2Cc; Thalhammer et al., 2017). These findings provide therefore a precise molecular basis for the involvement of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels in presynaptic homeostatic plasticity (Frank et al., 2006; Jakawich et al., 2010; Lazarevic et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011; Jeans et al., 2017) and highlight the importance of activity-dependent AS in homeostatic synaptic plasticity.

Although it is not known how network activity regulates this splicing event, it has recently been proposed that inclusion of exon 37a or 37b in CaV2.2 is consequent to differences in chromatin structure and transcription rates, rather than being directly regulated at the mRNA level (Javier et al., 2019; Lopez Soto and Lipscombe, 2020). Because splicing occurs mostly co-transcriptionally (Luco et al., 2011), rapid transcription of Cacna1b (the gene for the α1 subunit of CaV2.2) would lead to simultaneous availability to the splicing machinery of the two mutually exclusive exons. Direct competition between them would results in inclusion of the downstream stronger exon 37b. Conversely, a slow transcription rate would favor recruitment of the splicing machinery to the first upstream exon 37a, thus leading to inclusion of this weaker exon into the final transcript. Indeed, the zinc finger DNA-binding protein CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF), a well-known organizer of chromatin architecture, binds to the exon 37a locus of Cacna1b to promote inclusion of this exon (Javier et al., 2019; Lopez Soto and Lipscombe, 2020). This is likely because CTCF favors the formation of intragenic chromatin loops and slows down the elongation rate of the RNA polymerase II (Pol II; Shukla et al., 2011; Ruiz-Velasco et al., 2017). Importantly, CTCF binding is not constitutive but prevented by methylation of the Cacna1b exon 37a locus, which consequently leads to exon 37a exclusion (Javier et al., 2019; Lopez Soto and Lipscombe, 2020).

Because the methylation level of chromosomal DNA is key to both memory formation and homeostatic synaptic plasticity (Day and Sweatt, 2010; Meadows et al., 2015), it is conceivable that activity-dependent methylation and demethylation might regulate also the inclusion of exon 37a in Cacna1a during presynaptic homeostatic plasticity. According to databases of chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq1, ENCODE Project Consortium, 2012), CTCF binds indeed also to the Cacna1a exon 37a locus (Figure 2Cc).

Discussion: Implications of Activity-Dependent Alternative Splicing for Brain Disorders

Genome-wide transcriptomic studies indicate that AS is more prominent in the brain than in other tissues (Yeo et al., 2004; Pan et al., 2008). Accordingly, defects in AS have been implicated in neurological and neurodegenerative disorders (Raj and Blencowe, 2015; Furlanis and Scheiffele, 2018; Montes et al., 2019). AS defects can originate from mutations that alter either cis-acting elements on specific genes or trans-acting splicing factors affecting the splicing of multiple transcripts. As discussed briefly in this minireview article, the former mutations are prominent in mutually exclusive and cassette exons involved mostly in monogenic brain pathologies such as episodic ataxia type II, the latter are especially critical for multifactorial brain disorders, for example, for autism spectrum disorder (Gehman et al., 2011; Voineagu et al., 2011; Irimia et al., 2014; Quesnel-Vallières et al., 2016; Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis et al., 2018).

In both cases, to fully understand how defective AS alters circuit and brain function, it is important to consider that some AS events in the brain are regulated by network activity and that the outcome of the splicing process can in turn compensate for changes in activity levels, thus establishing negative feedback loops that make brain function especially resilient to damage. Rather than being direct, the effects of defective AS on brain function are therefore likely to be indirectly mediated by deficient or aberrant homeostatic plasticity mechanisms.

Elucidating the interplay between activity-dependent AS and homeostatic plasticity, as well as implementing new technologies, such as genome editing approaches aimed at correcting pathogenic mutations interfering with AS or at rebalancing splice isoform levels (Gapinske et al., 2018; Konermann et al., 2018; Thalhammer et al., 2018; Yuan et al., 2018), will help us to develop new and improved splicing therapies for brain disorders.

Author Contributions

AT, FJ, and LC contributed jointly to the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Benfenati for support for this article and G. Alberini for assistance with Chimera.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMPAR

AMPA-type glutamate receptor

- AS

alternative splicing

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CDF

Ca2+-dependent facilitation

- CTCF

CCCTC-binding factor

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- mEPSCs

miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents

- mGluR

metabotropic glutamate receptor

- nSR100

Ser/Arg repeat-related protein of 100 kDa

- nt

nucleotides

- REST

repressor element 1 silencing transcription factor

- SNP

single-nucleotide polymorphism

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- UTR

untranslated region

- VGCC

voltage-gated calcium channel.

Funding. The funding was provided by the Italian Institute of Technology and grants from Ataxia UK and Telethon (GGP19181) to LC.

References

- Andrade A., Denome S., Jiang Y. Q., Marangoudakis S., Lipscombe D. (2010). Opioid inhibition of N-type Ca2+ channels and spinal analgesia couple to alternative splicing. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1249–1256. 10.1038/nn.2643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ango F., Prézeau L., Muller T., Tu J. C., Xiao B., Worley P. F., et al. (2001). Agonist-independent activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors by the intracellular protein Homer. Nature 411, 962–965. 10.1038/35082096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babitch J. (1990). Channel hands. Nature 346, 321–322. 10.1038/346321b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baralle F. E., Giudice J. (2017). Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 437–451. 10.1038/nrm.2017.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell T. J., Thaler C., Castiglioni A. J., Helton T. D., Lipscombe D. (2004). Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron 41, 127–138. 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00801-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Johny M., Yang P. S., Niu J., Yang W., Joshi-Mukherjee R., Yue D. T. (2014). Conservation of Ca2+/calmodulin regulation across Na and Ca2+ channels. Cell 157, 1657–1670. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke J. D., Paletzki R. F., Aronson G. J., Hyman S. E., Gerfen C. R. (1998). A complex program of striatal gene expression induced by dopaminergic stimulation. J. Neurosci. 18, 5301–5310. 10.1523/jneurosci.18-14-05301.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottai D., Guzowski J. F., Schwarz M. K., Kang S. H., Xiao B., Lanahan A., et al. (2002). Synaptic activity-induced conversion of intronic to exonic sequence in Homer 1 immediate early gene expression. J. Neurosci. 22, 167–175. 10.1523/jneurosci.22-01-00167.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E., Soong T. W., Sutton K., Slaymaker S., Mathews E., Monteil A., et al. (1999). Splicing of α 1A subunit gene generates phenotypic variants of P- and Q-type calcium channels. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 407–415. 10.1038/8070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakeman P. R., Lanahan A. A., O’Brien R., Roche K., Barnes C. A., Huganir R. L., et al. (1997). Homer: a protein that selectively binds metabotropic glutamate receptors. Nature 386, 284–288. 10.1038/386284a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D., Chang S. Y., DeMaria C. D., Alvania R. S., Soong T. W., Yue D. T. (2004). Alternative splicing as a molecular switch for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J. Neurosci. 24, 6334–6342. 10.1523/jneurosci.1712-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevenet F., Brun C., Bañuls A. L., Jacq B., Christen R. (2006). TreeDyn: towards dynamic graphics and annotations for analyses of trees. BMC Bioinformatics 7:439. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani L. A., Vitale C., Dityatev A. (2019). Intra- and extracellular pillars of a unifying framework for homeostatic plasticity: a crosstalk between metabotropic receptors and extracellular matrix. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13:513. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. W., Müller M. (2015). Homeostatic control of presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 77, 251–270. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day J. J., Sweatt J. D. (2010). DNA methylation and memory formation. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1319–1323. 10.1038/nn.2666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diering G. H., Nirujogi R. S., Roth R. H., Worley P. F., Pandey A., Huganir R. L. (2017). Homer1a drives homeostatic scaling-down of excitatory synapses during sleep. Science 355, 511–515. 10.1126/science.aai8355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubes S., Favereaux A., Thoumine O., Letellier M. (2019). miRNA-dependent control of homeostatic plasticity in neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 13:536. 10.3389/fncel.2019.00536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermann E., Bucurenciu I., Goswami S. P., Jonas P. (2012). Nanodomain coupling between Ca2+ channels and sensors of exocytosis at fast mammalian synapses. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 7–21. 10.1038/nrn3125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENCODE Project Consortium . (2012). An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74. 10.1038/nature11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson M. G., Alseikhan B. A., Peterson B. Z., Yue D. T. (2001). Preassociation of calmodulin with voltage-gated Ca2+ channels revealed by FRET in single living cells. Neuron 31, 973–985. 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00438-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagni L., Worley P. F., Ango F. (2002). Homer as both a scaffold and transduction molecule. Sci. STKE 2002:re8. 10.1126/stke.2002.137.re8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes D., Carvalho A. L. (2016). Mechanisms of homeostatic plasticity in the excitatory synapse. J. Neurochem. 139, 973–996. 10.1111/jnc.13687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell S. W., Greenberg M. E. (2008). Signaling mechanisms linking neuronal activity to gene expression and plasticity of the nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 563–590. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavell S. W., Kim T. K., Gray J. M., Harmin D. A., Hemberg M., Hong E. J., et al. (2008). Genome-wide analysis of MEF2 transcriptional program reveals synaptic target genes and neuronal activity-dependent polyadenylation site selection. Neuron 60, 1022–1038. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank C. A., Kennedy M. J., Goold C. P., Marek K. W., Davis G. W. (2006). Mechanisms underlying the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Neuron 52, 663–677. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlanis E., Scheiffele P. (2018). Regulation of neuronal differentiation, function and plasticity by alternative splicing. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 34, 451–469. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100617-062826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapinske M., Luu A., Winter J., Woods W. S., Kostan K. A., Shiva N., et al. (2018). CRISPR-SKIP: programmable gene splicing with single base editors. Genome Biol. 19:107. 10.1186/s13059-018-1482-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardill B. R., Rivera-Acevedo R. E., Tung C. C., Okon M., McIntosh L. P., Van Petegem F. (2018). The voltage-gated sodium channel EF-hands form an interaction with the III-IV linker that is disturbed by disease-causing mutations. Sci. Rep. 8:4483. 10.1038/s41598-018-22713-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehman L. T., Stoilov P., Maguire J., Damianov A., Lin C. H., Shiue L., et al. (2011). The splicing regulator Rbfox1 (A2BP1) controls neuronal excitation in the mammalian brain. Nat. Genet. 43, 706–711. 10.1038/ng.841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida R., Musumeci S., D’Antoni S., Bonaccorso C. M., Giuffrida-Stella A. M., Oostra B. A., et al. (2005). A reduced number of metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptors are associated with constitutive homer proteins in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. J. Neurosci. 25, 8908–8916. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0932-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T., Wu M., Braunschweig U., Roth J., Han H., Best A. J., et al. (2018). Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 interrogation of splicing networks reveals a mechanism for recognition of autism-misregulated neuronal microexons. Mol. Cell 72, 510.e12–524.e12. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves T. D., Imbrici P., Kors E. E., Terwindt G. M., Eunson L. H., Frants R. R., et al. (2008). Premature stop codons in a facilitating EF-hand splice variant of CaV2.1 cause episodic ataxia type 2. Neurobiol. Dis. 32, 10–15. 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray A. C., Raingo J., Lipscombe D. (2007). Neuronal calcium channels: splicing for optimal performance. Cell Calcium 42, 409–417. 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatje K., Rahman R. U., Vidal R. O., Simm D., Hammesfahr B., Bansal V., et al. (2017). The landscape of human mutually exclusive splicing. Mol. Syst. Biol. 13:959. 10.15252/msb.20177728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermey G., Bluthgen N., Kuhl D. (2017). Neuronal activity-regulated alternative mRNA splicing. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 91, 184–193. 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holderith N., Lorincz A., Katona G., Rózsa B., Kulik A., Watanabe M., et al. (2012). Release probability of hippocampal glutamatergic terminals scales with the size of the active zone. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 988–997. 10.1038/nn.3137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J. H., Park J. M., Park S., Xiao B., Dehoff M. H., Kim S., et al. (2010). Homeostatic scaling requires group I mGluR activation mediated by Homer1a. Neuron 68, 1128–1142. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley M. A., Srinivasan K., Friedman B. A., Wang T. M., Yee A. X., Wang Y., et al. (2020). Genome-wide analysis of differential gene expression and splicing in excitatory neurons and interneuron subtypes. J. Neurosci. 40, 958–973. 10.1523/jneurosci.1615-19.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibata K., Sun Q., Turrigiano G. G. (2008). Rapid synaptic scaling induced by changes in postsynaptic firing. Neuron 57, 819–826. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimia M., Weatheritt R. J., Ellis J. D., Parikshak N. N., Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T., Babor M., et al. (2014). A highly conserved program of neuronal microexons is misregulated in autistic brains. Cell 159, 1511–1523. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakawich S. K., Nasser H. B., Strong M. J., McCartney A. J., Perez A. S., Rakesh N., et al. (2010). Local presynaptic activity gates homeostatic changes in presynaptic function driven by dendritic BDNF synthesis. Neuron 68, 1143–1158. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier E., Soto L., Lipscombe D. (2019). Cell-specific exon methylation and CTCF binding in neurons regulates calcium ion channel splicing and function. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 10.1101/2019.12.15.876185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeans A. F., van Heusden F. C., Al-Mubarak B., Padamsey Z., Emptage N. J. (2017). Homeostatic presynaptic plasticity is specifically regulated by P/Q-type Ca2+ channels at mammalian hippocampal synapses. Cell Rep. 21, 341–350. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammermeier P. J., Worley P. F. (2007). Homer 1a uncouples metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 from postsynaptic effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 104, 6055–6060. 10.1073/pnas.0608991104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato A., Ozawa F., Saitoh Y., Hirai K., Inokuchi K. (1997). vesl, a gene encoding VASP/Ena family related protein, is upregulated during seizure, long-term potentiation and synaptogenesis. FEBS Lett. 412, 183–189. 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00775-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Pinto S. M., Getnet D., Nirujogi R. S., Manda S. S., Chaerkady R., et al. (2014). A draft map of the human proteome. Nature 509, 575–581. 10.1038/nature13302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konermann S., Lotfy P., Brideau N. J., Oki J., Shokhirev M. N., Hsu P. D. (2018). Transcriptome engineering with RNA-targeting type VI-D CRISPR effectors. Cell 173, 665.e14–676.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korb E., Wilkinson C. L., Delgado R. N., Lovero K. L., Finkbeiner S. (2013). Arc in the nucleus regulates PML-dependent GluA1 transcription and homeostatic plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 874–883. 10.1038/nn.3429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarevic V., Schöne C., Heine M., Gundelfinger E. D., Fejtova A. (2011). Extensive remodeling of the presynaptic cytomatrix upon homeostatic adaptation to network activity silencing. J. Neurosci. 31, 10189–10200. 10.1523/jneurosci.2088-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber S. L., Llenos I. C., Miller C. L., Dulay J. R., Haybaeck J., Weis S. (2017). Homer1a protein expression in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. J. Neural Transm. 124, 1261–1273. 10.1007/s00702-017-1776-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letellier M., Elramah S., Mondin M., Soula A., Penn A., Choquet D., et al. (2014). miR-92a regulates expression of synaptic GluA1-containing AMPA receptors during homeostatic scaling. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 1040–1042. 10.1038/nn.3762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscombe D., Andrade A., Allen S. E. (2013). Alternative splicing: functional diversity among voltage-gated calcium channels and behavioral consequences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1828, 1522–1529. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luco R. F., Allo M., Schor I. E., Kornblihtt A. R., Misteli T. (2011). Epigenetics in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 144, 16–26. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez Soto E. J., Lipscombe D. (2020). Cell-specific exon methylation and CTCF binding in neurons regulate calcium ion channel splicing and function. Elife 9:e54879. 10.7554/eLife.54879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantuano E., Romano S., Veneziano L., Gellera C., Castellotti B., Caimi S., et al. (2010). Identification of novel and recurrent CACNA1A gene mutations in fifteen patients with episodic ataxia type 2. J. Neurol. Sci. 291, 30–36. 10.1016/j.jns.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M. D., Maejima T., Kuckelsberg D., Yoo J. W., Hyde R. A., Shah V., et al. (2011). Delayed postnatal loss of P/Q-type calcium channels recapitulates the absence epilepsy, dyskinesia, and ataxia phenotypes of genomic Cacna1a mutations. J. Neurosci. 31, 4311–4326. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5342-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Ortiz W., Cardozo T. J. (2018). An improved method for modeling voltage-gated ion channels at atomic accuracy applied to human cav channels. Cell Rep. 23, 1399–1408. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera A. G., Wang Z. (2014). A day in the life of the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 108–121. 10.1038/nrm3742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matosin N., Fernandez-Enright F., Lum J. S., Engel M., Andrews J. L., Gassen N. C., et al. (2016). Molecular evidence of synaptic pathology in the CA1 region in schizophrenia. NPJ Schizophr. 2:16022. 10.1038/npjschz.2016.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauger O., Scheiffele P. (2017). Beyond proteome diversity: alternative splicing as a regulator of neuronal transcript dynamics. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 45, 162–168. 10.1016/j.conb.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows J. P., Guzman-Karlsson M. C., Phillips S., Holleman C., Posey J. L., Day J. J., et al. (2015). DNA methylation regulates neuronal glutamatergic synaptic scaling. Sci. Signal. 8:ra61. 10.1126/scisignal.aab0715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montes M., Sanford B. L., Comiskey D. F., Chandler D. S. (2019). RNA splicing and disease: animal models to therapies. Trends Genet. 35, 68–87. 10.1016/j.tig.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori M., Konno T., Ozawa T., Murata M., Imoto K., Nagayama K. (2000). Novel interaction of the voltage-dependent sodium channel (VDSC) with calmodulin: does VDSC acquire calmodulin-mediated Ca2+-sensitivity? Biochemistry 39, 1316–1323. 10.1021/bi9912600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Harada H., Kamasawa N., Matsui K., Rothman J. S., Shigemoto R., et al. (2015). Nanoscale distribution of presynaptic Ca2+ channels and its impact on vesicular release during development. Neuron 85, 145–158. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. M., Schreiner D., Xiao L., Traunmuller L., Bornmann C., Scheiffele P. (2016). An alternative splicing switch shapes neurexin repertoires in principal neurons versus interneurons in the mouse hippocampus. Elife 5:e22757. 10.7554/eLife.22757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris A. D., Calarco J. A. (2012). Emerging roles of alternative pre-mRNA splicing regulation in neuronal development and function. Front. Neurosci. 6:122. 10.3389/fnins.2012.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q., Shai O., Lee L. J., Frey B. J., Blencowe B. J. (2008). Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 40, 1413–1415. 10.1038/ng.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pecoraro-Bisogni F., Lignani G., Contestabile A., Castroflorio E., Pozzi D., Rocchi A., et al. (2018). REST-dependent presynaptic homeostasis induced by chronic neuronal hyperactivity. Mol. Neurobiol. 55, 4959–4972. 10.1007/s12035-017-0698-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. Z., DeMaria C. D., Adelman J. P., Yue D. T. (1999). Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+ -dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels. Neuron 22, 549–558. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80709-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson B. Z., Lee J. S., Mulle J. G., Wang Y., de Leon M., Yue D. T. (2000). Critical determinants of Ca2+-dependent inactivation within an EF-hand motif of L-type Ca2+ channels. Biophys. J. 78, 1906–1920. 10.1016/s0006-3495(00)76739-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl M., Bortfeldt R. H., Grützmann K., Schuster S. (2013). Alternative splicing of mutually exclusive exons—a review. Biosystems 114, 31–38. 10.1016/j.biosystems.2013.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzi D., Lignani G., Ferrea E., Contestabile A., Paonessa F., D’Alessandro R., et al. (2013). REST/NRSF-mediated intrinsic homeostasis protects neuronal networks from hyperexcitability. EMBO J. 32, 2994–3007. 10.1038/emboj.2013.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel-Vallières M., Dargaei Z., Irimia M., Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T., Ip J. Y., Wu M., et al. (2016). Misregulation of an activity-dependent splicing network as a common mechanism underlying autism spectrum disorders. Mol. Cell 64, 1023–1034. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raingo J., Castiglioni A. J., Lipscombe D. (2007). Alternative splicing controls G protein-dependent inhibition of N-type calcium channels in nociceptors. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 285–292. 10.1038/nn1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj B., Blencowe B. J. (2015). Alternative splicing in the mammalian nervous system: recent insights into mechanisms and functional roles. Neuron 87, 14–27. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj B., O’Hanlon D., Vessey J. P., Pan Q., Ray D., Buckley N. J., et al. (2011). Cross-regulation between an alternative splicing activator and a transcription repressor controls neurogenesis. Mol. Cell 43, 843–850. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebola N., Reva M., Kirizs T., Szoboszlay M., Lorincz A., Moneron G., et al. (2019). Distinct nanoscale calcium channel and synaptic vesicle topographies contribute to the diversity of synaptic function. Neuron 104, 693.e9–710.e9. 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronesi J. A., Collins K. A., Hays S. A., Tsai N. P., Guo W., Birnbaum S. G., et al. (2012). Disrupted Homer scaffolds mediate abnormal mGluR5 function in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 431–440, S1. 10.1038/nn.3033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Velasco M., Kumar M., Lai M. C., Bhat P., Solis-Pinson A. B., Reyes A., et al. (2017). CTCF-mediated chromatin loops between promoter and gene body regulate alternative splicing across individuals. Cell Syst. 5, 628.e6–637.e6. 10.1016/j.cels.2017.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanzenbächer C. T., Langer J. D., Schuman E. M. (2018). Time- and polarity-dependent proteomic changes associated with homeostatic scaling at central synapses. Elife 7:e33322. 10.7554/eLife.33322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanzenbächer C. T., Sambandan S., Langer J. D., Schuman E. M. (2016). Nascent proteome remodeling following homeostatic scaling at hippocampal synapses. Neuron 92, 358–371. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaukowitch K., Reese A. L., Kim S. K., Kilaru G., Joo J. Y., Kavalali E. T., et al. (2017). An intrinsic transcriptional program underlying synaptic scaling during activity suppression. Cell Rep. 18, 1512–1526. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.01.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner D., Nguyen T. M., Russo G., Heber S., Patrignani A., Ahrné E., et al. (2014). Targeted combinatorial alternative splicing generates brain region-specific repertoires of neurexins. Neuron 84, 386–398. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner D., Simicevic J., Ahrné E., Schmidt A., Scheiffele P. (2015). Quantitative isoform-profiling of highly diversified recognition molecules. Elife 4:e07794. 10.7554/eLife.07794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J. D., Rumbaugh G., Wu J., Chowdhury S., Plath N., Kuhl D., et al. (2006). Arc/Arg3.1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors. Neuron 52, 475–484. 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi-Yamaguchi Y., Furuichi T. (2007). The homer family proteins. Genome Biol. 8:206. 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S., Kavak E., Gregory M., Imashimizu M., Shutinoski B., Kashlev M., et al. (2011). CTCF-promoted RNA polymerase II pausing links DNA methylation to splicing. Nature 479, 74–79. 10.1038/nature10442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong T. W., DeMaria C. D., Alvania R. S., Zweifel L. S., Liang M. C., Mittman S., et al. (2002). Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel α12.1 subunits: implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J. Neurosci. 22, 10142–10152. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10142.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. A., Ito H. T., Cressy P., Kempf C., Woo J. C., Schuman E. M. (2006). Miniature neurotransmission stabilizes synaptic function via tonic suppression of local dendritic protein synthesis. Cell 125, 785–799. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szumlinski K. K., Kalivas P. W., Worley P. F. (2006). Homer proteins: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 16, 251–257. 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalhammer A., Contestabile A., Ermolyuk Y. S., Ng T., Volynski K. E., Soong T. W., et al. (2017). Alternative splicing of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels shapes presynaptic plasticity. Cell Rep. 20, 333–343. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thalhammer A., Jaudon F., Cingolani L. A. (2018). Combining optogenetics with artificial microRNAs to characterize the effects of gene knockdown on presynaptic function within intact neuronal circuits. J. Vis. Exp. 133:e57223. 10.3791/57223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutlein B., Gokce O., Quake S. R., Südhof T. C. (2014). Cartography of neurexin alternative splicing mapped by single-molecule long-read mRNA sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 111, E1291–E1299. 10.1073/pnas.1403244111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrigiano G. (2011). Too many cooks? Intrinsic and synaptic homeostatic mechanisms in cortical circuit refinement. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 89–103. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich B., Ushkaryov Y. A., Südhof T. C. (1995). Cartography of neurexins: more than 1000 isoforms generated by alternative splicing and expressed in distinct subsets of neurons. Neuron 14, 497–507. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90306-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loo K. M., Schaub C., Pernhorst K., Yaari Y., Beck H., Schoch S., et al. (2012). Transcriptional regulation of T-type calcium channel CaV3.2: bi-directionality by early growth response 1 (Egr1) and repressor element 1 (RE-1) protein-silencing transcription factor (REST). J. Biol. Chem. 287, 15489–15501. 10.1074/jbc.m111.310763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigues S., Gastaldi M., Massacrier A., Cau P., Valmier J. (2002). The α1A subunits of rat brain calcium channels are developmentally regulated by alternative RNA splicing. Neuroscience 113, 509–517. 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00213-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voineagu I., Wang X., Johnston P., Lowe J. K., Tian Y., Horvath S., et al. (2011). Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature 474, 380–384. 10.1038/nature10110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuong C. K., Black D. L., Zheng S. (2016). The neurogenetics of alternative splicing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 17, 265–281. 10.1038/nrn.2016.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang E. T., Sandberg R., Luo S., Khrebtukova I., Zhang L., Mayr C., et al. (2008). Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 456, 470–476. 10.1038/nature07509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyrer C., Turecek J., Niday Z., Liu P. W., Nanou E., Catterall W. A., et al. (2019). The role of CaV2.1 channel facilitation in synaptic facilitation. Cell Rep. 26, 2289.e3–2297.e3. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B., Tu J. C., Petralia R. S., Yuan J. P., Doan A., Breder C. D., et al. (1998). Homer regulates the association of group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors with multivalent complexes of homer-related, synaptic proteins. Neuron 21, 707–716. 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80588-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo G., Holste D., Kreiman G., Burge C. B. (2004). Variation in alternative splicing across human tissues. Genome Biol. 5:R74. 10.3390/ijms20163977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J., Ma Y., Huang T., Chen Y., Peng Y., Li B., et al. (2018). Genetic modulation of RNA splicing with a CRISPR-guided cytidine deaminase. Mol. Cell 72, 380.e7–394.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Chen K., Sloan S. A., Bennett M. L., Scholze A. R., O’Keeffe S., et al. (2014). An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 34, 11929–11947. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C., Dreosti E., Lagnado L. (2011). Homeostatic synaptic plasticity through changes in presynaptic calcium influx. J. Neurosci. 31, 7492–7496. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6636-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuhlke R. D., Pitt G. S., Deisseroth K., Tsien R. W., Reuter H. (1999). Calmodulin supports both inactivation and facilitation of L-type calcium channels. Nature 399, 159–162. 10.1038/20200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]