1. RESEARCH LETTER

A novel coronavirus, currently identified as COVID‐19, was recently defined as the cause of a cluster of patients with pneumonia of unknown origin that was initially reported from Wuhan, Hubei Province, People's Republic of China. 1 In a recent summary of reports of 72,314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the overall fatality rate of COVID‐19 was estimated in 2.3%, although this figure was greater (8.0%) in the population aged between 70 and 79 years, further increasing with increasing age up to 14.8% in patients older than 80 years. 2 Moreover, the case fatality rate was higher in patients affected by various comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, hypertension and cancer. 2

Beginning on 21 February 2020, when the first cluster of 16 patients were confirmed in the Lombardy Region, COVID‐19 infection subsequently spread in Italy, and as of today—when the World Health Organization (WHO) has officially declared that COVID‐19 can be considered pandemic—the number of COVID‐19 cases recorded in Italy is 15 113 with 1016 deaths and 1258 patients recovered from infection. 3 , 4 , 5 Although the infection is mainly characterised by fever and respiratory symptoms such as cough and dyspnoea, with instrumental evidence of bilateral atypical pneumonia, and the main route of transmission is through respiratory droplets from coughing and sneezing, more recently the WHO‐China Joint Mission on COVID‐2019 emphasised the finding that viral RNA can be detected in stools in as much as 30% of cases, persisting for up to 4‐5 weeks, although it is not clear whether this might correlate with the presence of infectious virus. 1 , 3 , 5 Noteworthy, there is evidence that COVID‐19 may infect glandular cells of the digestive tract, including the rectum, determining inflammatory infiltrates characterised by the presence of interstitial oedema and lymphoplasmocytosis, although the actual association of this pathological evidence with gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea, which can be present in a proportion of patients with COVID‐19 infection, is still not clear. 1 , 6 , 7 Noteworthy, COVID‐19 infection is associated with a marked increase in levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin‐1B and tumour necrosis factor‐alpha (TNF‐α), both implicated in the pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), a disease characterised by relapse and remission phases, whose main clinical manifestations are fever, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, and where there is a complex interplay between inflammatory and remodelling processes involving several cytokines. 3 , 8 , 9

Our unit serves as a tertiary referral centre for the diagnosis and cure of IBD within a University Hospital in Genoa (approximately, 600 000 inhabitants), Italy. The most effective treatments for patients affected with IBD are immunosuppressive drugs, such as antimetabolites, and biological therapy such as anti‐TNF‐α monoclonal antibodies. 10 , 11 IBD treatment with these drugs is inherently burdened by some degree of immunosuppression and by a greater likelihood of infections, although there does not seem to be a strong association between the occurrence of infections and biological drug dose. 12 , 13 This notwithstanding, patients with IBD are often concerned regarding the potential for the occurrence of immunosuppression‐related events, and in general, in patients with IBD, the occurrence of stressor events may represent a trigger for disease relapse. 14

The recent measures adopted by the Italian government in order to contain the diffusion of COVID‐19 infection had an understandable and significant impact on ordinary hospital activities, including outpatients management, as well as on personal life of the population, obviously including patients with IBD followed at our centre.

In order to assess how general concerns regarding COVID‐19 infection and potential anxieties associated with fears of contracting the infection, including worries related to drug‐induced immunosuppression, affected the behaviour of patients with IBD, we evaluated the proportion of patients who maintained the assigned appointments for scheduled visits at our centre, and monitored the number and reasons for email messages received by the outpatient centre dedicated email address.

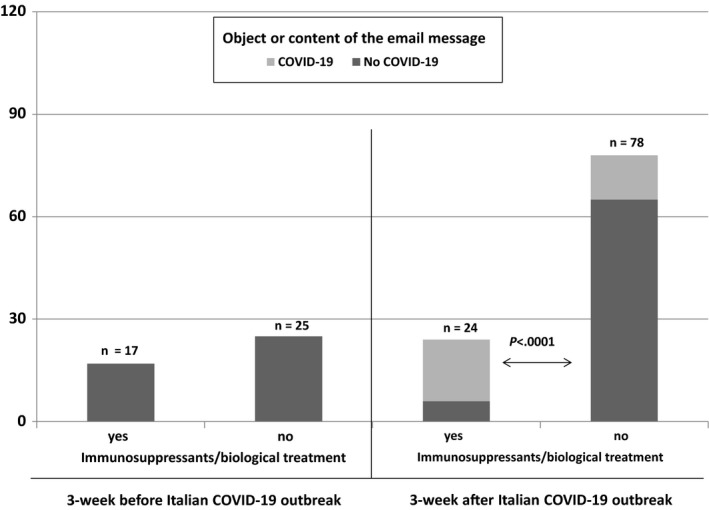

All in all, during the last 3 weeks since 21 February 2020, 36 (42.9%) of the 84 scheduled outpatients visits were cancelled. The majority (88.8%, n = 32) of the cancelled visits were so due to government indication to prevent any potentially avoidable contact of patients with hospitals, and therefore, nonurgent visits were cancelled and rescheduled by hospital personnel, while in 11.2% of cases (n = 4), the visits were cancelled by the patients themselves because of fears related to COVID‐19 infection. Among the 48 patients who presented for their scheduled visit, 15 (31.2%) were on immunosuppressant drugs, and overall, none of the 48 patients reported symptoms suggestive of COVID‐19 infection. Noteworthy, the number of email messages received at the dedicated email inbox of the centre progressively increased, up to 17 daily email messages, with a mean of 7 messages per working day. Indeed, the total number of email messages in the 3‐week period of interest was 102, with 24 messages sent by patients treated with biological or immunosuppressive drugs, of whom 18 (75.0%) had COVID‐19 as object, while 78 email messages were from patients with IBD not receiving any immunosuppressive therapy, and only 13 of them (16.7%) with a request of information on COVID‐19 and IBD as object (P < .0001). In comparison, in the 3‐week period preceding 21 February 2020—despite the epidemic of COVID‐19 was by large renowned in the public, and isolated cases had already appeared in Italy—we received a total of 42 email messages (−59%), with a mean of 3 email messages per working day: 17 and 25 messages were from patients on immunosuppressive or biological drugs or on standard medications, respectively, and none of them contained any reference to COVID‐19 (Figure 1). Since the beginning of the COVID‐19 epidemic in our country, 2 patients autonomously decided to discontinue treatment with a biological drug, while in 2 patients, the decision to delay initiation of immunosuppressant therapy was agreed upon by physicians and patients following concerns of the latter regarding the beginning of treatment in this period. Lastly, in one patient, a postponement in dose intensification of a biological drug was decided by the physician in charge of the patient after having carefully balanced the risks associated with activity of the IBD and those related to the increase in the number of visits to the hospital to receive drug infusions and more frequent controls.

FIGURE 1.

Number and proportion of patients who sent email messages to the dedicated email inbox of the inflammatory bowel disease of our centre subdivided according to two 3‐week periods, before and after COVID‐19 outbreak in Italy and to the object or content of message

All in all, although the possible greater susceptibility to COVID‐19 infection, or the potential for different clinical picture and severity of disease in patients with IBD on, or off, immunosuppressive or biological treatment is at present unknown, we observed that the diffusion of infection has raised concerns among patients with IBD, as in the general population, and we demonstrated that this concern was significantly more tangible among patients with IBD on immunosuppressive drugs. We feel that in this time and age of great concerns regarding the health and economic fallout of the COVID‐19 pandemic, every effort should be pursued by specialised centres caring for patients with IBD, and we have observed that with adequate counselling and telematics tools to provide patients with prompt and reliable answers, only 2 of the 107 patients on biological drugs withdrew treatment (1.9%), and none of the patients on clinical trials or on antimetabolites. However, we also feel that in this moment in history, every effort should be put in place in order to facilitate patients’ compliance with both ordinary care and more complex treatment for IBD, by stratifying patients considering age, comorbidities and disease activity, enhancing telemedicine use for fragile patients or those in remission, improving home delivery of medicines and, when possible, adequate facilities for infusions of biological or experimental drugs for patients with moderate‐severe activity of disease.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bassetti M, Vena A, Giacobbe DR. The novel Chinese coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infections: challenges for fighting the storm. Eur J Clin Invest. 2020;50:e13209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed on March 12, 2020.

- 5. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who‐director‐general‐s‐opening‐remarks‐at‐the‐media‐briefing‐on‐covid‐19–‐11‐march‐2020. Accessed on March 12, 2020.

- 6. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/who‐china‐joint‐mission‐on‐covid‐19‐final‐report.pdf. Accessed on March 12, 2020.

- 7. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for Gastrointestinal Infection of SARS‐CoV‐2. Gastroenterology. 2020;pii:S0016–5085(20)30282–1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nikolopoulou V, Katsakoulis E, Tsiotos P, Thomopoulos K, Salsaa B, Zoumbos N. Production of interleukin‐1b and tumor necrosis factor‐α by peripheral blood human mononuclear cells in active and inactive stages of ulcerative colitis. Z Gastroenterol. 1995;33:9‐12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carbone F, Bodini G, Brunacci M, et al. Reduction in TIMP‐2 serum levels predicts remission of inflammatory bowel diseases. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48:e13002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, et al. ECCO guidelines on therapeutics in Crohn's disease: medical treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:4‐22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Third European evidence‐based consensus on diagnosis and management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 2, Current Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:769‐784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bodini G, Demarzo MG, Saracco M, et al. High anti‐TNF alfa drugs trough levels are not associated with the occurrence of adverse events in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:1220‐1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Giannini EG, Demarzo MG, Bodini G. Reproducibility and transportability of the absence of incremental infectious adverse events in patients with higher anti‐TNF drug levels. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25:e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Torres J, Ellul P, Langhorst J, et al. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation Topical review on complementary medicine and psychotherapy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:673‐685e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]