Abstract

Sporotrichosis infections may cause cutaneous lesions mimicking other infectious or non-infectious causes such as pyoderma gangrenosum. We present a case of cutaneous sporotrichosis misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum and treated with immunosuppressants for 17 months leading to exacerbation and atypical morphology mimicking Histoplasma organisms on biopsy. Exclusion of infection prior to diagnosing pyoderma gangrenosum is important to prevent iatrogenic immunosuppression, demonstrating the challenges with application of the updated pyoderma gangrenosum diagnostic criteria.

Keywords: Pyoderma gangrenosum, sporotrichosis infection, sporotrichosis schenckii, pyoderma gangrenosum diagnostic criteria, cutaneous sporotrichosis, ulcer, deep fungal infection, histoplasmosis mimic

Introduction

Cutaneous sporotrichosis infections can be difficult to visually distinguish from other ulcerative or infiltrative lesions. The differential for ulcerative lesions includes infectious and non-infectious causes such as malignancies, vascular disorders, and inflammatory disorders. Sporotrichosis lesions have been misdiagnosed as ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) due to similar clinical appearance or lack of positive culture or histological stains.1–8 Weenig et al.1 found that 11/64 (17%) lesions misdiagnosed as PG were caused by primary cutaneous infections, with the pathogen being Sporothrix schenckii in 5/11 cases. As immunosuppressive therapies are standard of care for treating PG, exclusion of infectious etiology is especially important prior to starting therapy. Updated ulcerative PG diagnostic criteria require a biopsy demonstrating neutrophilic inflammation, making diagnosis of PG no longer purely a diagnosis of exclusion.9 This case highlights the importance of exclusion of infection as a diagnostic criterion.

Here, we report a case of cutaneous sporotrichosis misdiagnosed and treated for 17 months as ulcerative PG, leading to exacerbation and atypical morphology mimicking Histoplasma organisms on re-biopsy.

Case report

A 78-year-old male presented with a non-healing left arm ulcer in June 2017 (Figure 1). A 5-mm punch biopsy showed extensive neutrophilic inflammation and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining for fungal organisms was reported as negative, and simultaneous tissue culture was not done. The case diagnosis was compatible with PG. Various immunosuppressive treatments were tried for a year leading to worsening progression.

Figure 1.

View of the patient’s left upper arm prior to antifungal treatment showing cribriform ulceration.

The patient presented to our clinic November 2018 and was being treated with IV immunoglobulin (IVIG), prednisone, and ustekinumab for 7 months with severe disease progression. Treatment with cyclosporine and mycophenolate previously failed due to hypertension and leg swelling, and gastrointestinal disturbances, respectively. No risk factors such as environmental exposures, previous occupation, and travel were reported. Lymphangitis and lymph node involvement was not present.

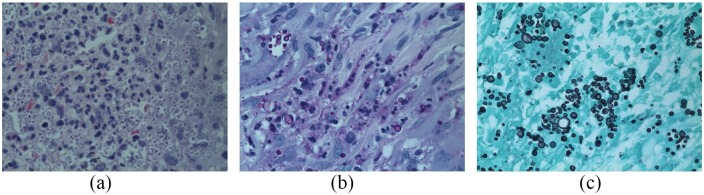

A 4-mm punch biopsy of the ulcer edge showed numerous three- to four-micron intra-cytoplasmic yeasts within histiocytes (Figure 2(a)). Hundreds of intracellular organisms were PAS stain-positive and Grocott’s methenamine silver stain-positive (Figure 2(b) and (c)), ranging from 3 to 12 microns with some budding yeasts. Despite morphological consistency with Histoplasmosis duboisii or capsulatum, tissue cultures led to isolation of S. schenckii species complex, an interesting report in histopathology.

Figure 2.

Biopsy from November 2018. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin stain (magnification 400×) showing intra-histiocytic and extracellular yeasts measuring from 3 to 5 microns, resembling Histoplasma organisms. (b) Periodic acid–Schiff stain (magnification 400×) showing yeasts measuring 3–12 microns in diameter within histiocytes. (c) Grocott’s methenamine silver stain (magnification 400×).

Prednisone was tapered and itraconazole (200 mg/day) was promptly started. Treatment continued for 4 months leading to complete wound regression and healing of the left arm (Figure 3). He received standard wound care.

Figure 3.

View of the patient’s left upper arm 3 months post-treatment.

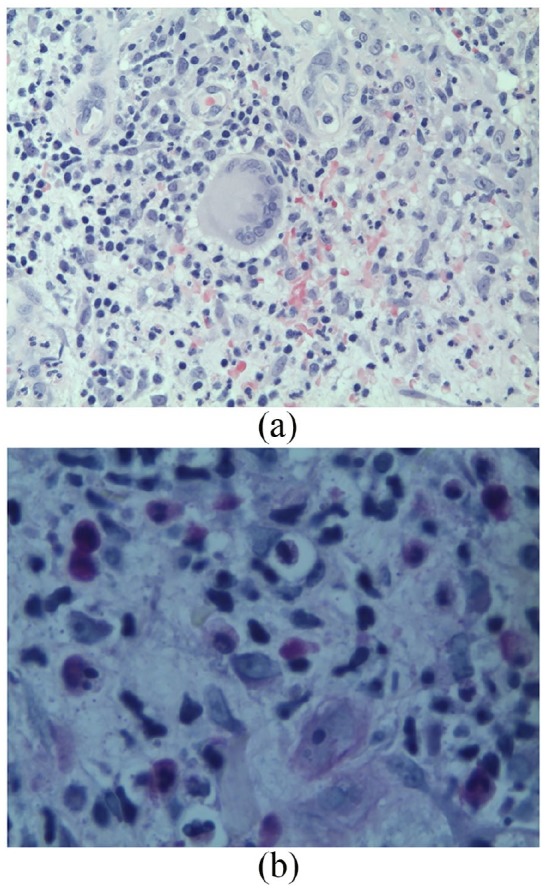

A second opinion of the initial biopsy in June 2017 reported the rare presence of PAS-positive yeast (Figure 4(a) and (b)) in the original biopsy.

Figure 4.

Biopsy from June 2017. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin stain from the biopsy showing suppurative dermatitis below an ulcer, in which focally a multinucleated histiocyte is visible (magnification 400×). (b) A single PAS-positive yeast organism measuring 4–6 microns found on re-examination (magnification 640×).

Discussion

We report a case of chronic S. schenckii cutaneous infection initially misdiagnosed as PG due to a lack of tissue culture complemented with overlook in identifying PAS-positive organisms. This led to mistreatment and severe exacerbation of the patient’s lesion for 17 months. Re-biopsy showed atypical histologic morphology of S. schenckii as hundreds of intra-cytoplasmic yeasts within histiocytes, mimicking Histoplasmosis organisms. Tissue culture results confirmed S. schenckii infection. This picture is not usually seen in a biopsy of typical sporotrichosis cases and was suspected to be caused by chronic iatrogenic immunosuppression.

S. schenckii is an environmentally ubiquitous thermodimorphic fungus existing worldwide in a filamentous form at 25°C and transforming into yeast-like cells at 35°C–37°C. Common sources of infection to trauma-induced wounds include rose thorns, soil, hay, decaying vegetation, plants, animal feces, and zoonotic transmission from cats.10

Cutaneous manifestations of sporotrichosis include lymphocutaneous, fixed cutaneous, and disseminated cutaneous. In cutaneous infections, a papulonodular lesion develops within 2–4 weeks of inoculation, followed by ulceration and purulent discharge. Lymphocutaneous infections occur with subsequent spread to lymphatic channels and accounts for up to 80% of sporotrichosis infections.11,12 Extracutaneous sporotrichosis manifestations including pulmonary, osteoarticular, mucosal, disseminated, and meningeal sporotrichosis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.11,13

An ulcerated lesion may have an infectious or non-infectious differential (Table 1). Wound culture is the diagnostic gold standard, but may take more than 5 days to grow. A PAS-positive stain was reported in only 3.2%–19.7% of sporotrichosis infections due to low fungal burden in early infections.14,15

Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of cutaneous sporotrichosis.

| Infectious causes |

|---|

| Fungal • Histoplasmosis • Cryptococcus • Blastomycosis • Coccidioidomycosis |

| Bacterial • Cutaneous anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) • Pyodermatitis (Staphylococcus, Streptococcus) • Cutaneous tuberculosis • Cat-scratch disease (Bartonella henselae) • Syphilis (Treponema pallidum) • Tularemia (Francisella tularensis) • Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), M. marinum M. chelonae, and M. ulcerans) • Cutaneous nocardiosis (Nocardia brasiliensis) • Tertiary syphilis (Treponema pallidum) |

| Parasitic • Leishmaniasis (Leishmania braziliensis) • Cutaneous amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica) |

| Non-infectious causes |

| • Pyoderma gangrenosum • Osteomyelitis • Cutaneous sarcoidosis • Sweet’s syndrome • Wegener’s granulomatosis |

Itraconazole is the first-line treatment for cutaneous sporotrichosis infections, with open treatment trials reporting 90%–100% success rate if continued up to 4 weeks after treatment resolution.16–18 Liposomal amphotericin B is often used for severe or extracutaneous manifestations.3,19 Local heat therapy has also been reported to be effective as temperatures >38°C minimize sporotrichosis growth.6,20

Many reported cases of sporotrichosis misdiagnosed as PG were treated with immunosuppressive treatment leading to exacerbation (Table 2). Delayed diagnosis led to reports of superinfection, disseminated sporotrichosis, and osteoarticular sporotrichosis.7,8 Because both ulcerative PG and fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis occur in absence of lymphatic involvement, the clinical picture is difficult to distinguish.3,8 In addition, 50% of sporotrichosis infections are not correlated with a history of trauma, gardening, or rose exposure.2

Table 2.

Case reports of sporotrichosis infections misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum.

| Author, year | Age and sex | History | Risk factors | Site of lesion | What led to initial diagnosis of PG? | Initial management | Sporotrichosis diagnosis (Method) | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byrd et al., 20012 | 59 and F | 6 months Hx of ulcerated nodule | Ankle prick by rose thorn | Right leg | Unknown, but was diagnosed as PG after ulceration of lesion | Prednisone, oral antibiotics, azathioprine, and cyclosporine | Cutaneous sporotrichosis (Tissue culture, positive PAS stain) | Itraconazole (200 mg/TID) for 18 months |

| Yang et al., 20063 | 40 and M | 1 year Hx of non-healing ulcer with history of sarcoidosis | Blackberry picking | Left forearm | Two previously nondiagnostic biopsies, negative tissue culture, and history of pulmonary sarcoidosis led to suspicion of ulcerative cutaneous sarcoidosis and pyoderma gangrenosum | Prednisone | Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis (Biopsy and culture) | Itraconazole (200 mg/d) for 2 months |

| Lima et al., 20174 | 39 and F | Incomplete response to itraconazole from 2 years ago | Scratched by sporotrichosis-infected cat | Abdomen progressing to right arm | Incomplete response to itraconazole from 2 years ago led to revision of diagnosis to PG | Corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, infliximab, non-opioid analgesics, and morphine | Disseminated cutaneous sporotrichosis (Biopsy, tissue culture) | Liposomal amphotericin B (400 mg/day) for 6 weeks followed by itraconazole (400 mg/d) for 12 months |

| Charles et al., 20175 | 57 and F | 10 months Hx of three enlarging ulcers after arthropod bite | Trauma | Right arm | Biopsy showed granulomatous reaction, incomplete response to itraconazole, ulcerative characteristic, and severely painful pattern led to presumed diagnosis of PG with secondary infection | Levofloxacin, ceftriaxone, prednisone, penicillin, and topical clobetasol | Cutaneous sporotrichosis (Tissue culture, positive PAS stain) | Itraconazole (200 mg/d) for 3 months followed by 200 mg/BID |

| Takazawa et al., 20186 | 47 and M | 4 months Hx of skin ulcer on leg after fall | Trauma | Right lower leg | Medical history of ulcerative colitis and clinical presentation of skin ulcer | Topical steroid | Fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis (Tissue culture, PAS stain, PCR) | Potassium iodide (500 mg) for 2 weeks followed by 1000 mg for 3 weeks |

| Saeed et al., 20197 | 35 and F | Fell on right forearm | Cat owner, previously worked as a landscaper | Legs, arm, and abdomen | Negative stains and numerous ulcers | Prednisone doxycycline | Osteoarticular and disseminated sporotrichosis (Tissue culture) | Liposomal amphotericin B for 28 days, itraconazole (200 mg/TID followed by 200 mg/BID). Amphotericin (4 mg/kg/d) for 3 weeks followed by posaconazole (300 mg/d) for 12 months |

| White et al., 20198 | 62 and M | 1 month Hx of thigh lesion after playing golf | Left thigh | Atypical presentation ulcer without lymphocutaneous spread | Cephalexin for group B streptococcus prednisone, cyclosporine, ustekinumab, and IVIG | Disseminated sporotrichosis (Tissue and blood culture) | Liposomal amphotericin B (5 mg/kg IV daily), posaconazole (300 mg/BID followed by 300 mg/d). Itraconazole (200 mg/q8 h × 9 followed by 200 mg/q12 h) for 10 months after discharge; terbinafine (250 mg/d) later added due to wound progression | |

| Present case | 78 and M | No relevant history | None | Left arm | Negative PAS stain, and lack of tissue culture | Cyclosporine, mycophenolate, IVIG, prednisone, and ustekinumab | Fixed cutaneous sporotrichosis (Tissue culture) | Itraconazole (200 mg/d) for 4 months |

PG: pyoderma gangrenosum; PAS: periodic acid–Schiff; IVIG: IV immunoglobulin; BID: two times a day; TID: three times a day.

In 2018, Maverakis et al. published revised diagnostic criteria for diagnosing ulcerative PG.8 The major diagnostic criterion of histological presence of neutrophilic infiltrate at the ulcer edge must be met along with four other minor diagnostic criteria (Table 3). Under previous diagnostic criteria of exclusion, our case would not have satisfied the PG diagnostic criterion as a proper exclusion of infection was not done. However, under the new diagnostic criteria where exclusion of infectious causes is not required, potential for misdiagnosis and treatment exacerbation increases.

Table 3.

New diagnostic criteria for ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum.

| Major diagnostic criterion—Must be met: Biopsy of ulcer edge demonstrates neutrophilic infiltrate |

| Minor diagnostic criterion—At least four must be met: Pathergy(ulcer occuring at the site of trauma) Exclusion of infection via histological stains and tissue culture Pathergya History (personal or family) of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis History of papule pustule, or vesicle that rapidly ulcerated Peripheral erythema, undermining border, and tenderness at site of ulceration Multiple ulcerations with at least one occurring on anterior lower leg Cribriform or “wrinkled paper” scar(s) at site of healed ulcer Decrease in ulcer size within 1 month of initiating immunosuppressive medication(s) |

Source: Modified from Maverakis et al. (2018).

Ulcers occurring at trauma sites should extend past the area of trauma.

Ultimately, this case highlights the importance of tissue culture in excluding infectious causes before diagnosing PG and presents an atypical S. schenckii morphology mimicking Histoplasma organisms in chronically immunosuppressed infections.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Weenig RH, Davis MDP, Dahl PR, et al. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. New Engl J Med 2002; 347(18): 1412–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Byrd DR, El-Azhary RA, Gibson LE, et al. Sporotrichosis masquerading as pyoderma gangrenosum: case report and review of 19 cases of sporotrichosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2001; 15(6): 581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang DJ, Krishnan RS, Guillen DR, et al. Disseminated sporotrichosis mimicking sarcoidosis. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45(4): 450–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lima RB, Jeunon-Sousa MAJ, Jeunon T, et al. Sporotrichosis masquerading as pyoderma gangrenosum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017; 31(12): e539–e541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Charles K, Lowe L, Shuman E, et al. Painful linear ulcers: a case of cutaneous sporotrichosis mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. JAAD Case Report 2017; 3(6): 519–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Takazawa M, Harada K, Kakurai M, et al. Case of pyoderma gangrenosum-like sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix globosa in a patient with ulcerative colitis. J Dermatol 2018; 45(8): e226–e227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Saeed L, Weber RJ, Puryear SB, et al. Disseminated cutaneous and osteoarticular sporotrichosis mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019; 6(10): ofz395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. White M, Adams L, Phan C, et al. Disseminated sporotrichosis following iatrogenic immunosuppression for suspected pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19(11): e385–e391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154(4): 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(4): 633–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lopes-Bezerra LM, Schubach A, Costa RO. Sporothrix schenckii and sporotrichosis. Anais Da Academia Brasileira De Ciências 2006; 78: 293–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Orofino-Costa R, Macedo PM, Rodrigues AM, et al. Sporotrichosis: an update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An Bras Dermatol 2017; 92(5): 606–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Almeida-Paes R, de Oliveira MM, Freitas DF, et al. Sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Sporothrix brasiliensis is associated with atypical clinical presentations. Plos Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8(9): e3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Sharma RC, et al. Cutaneous sporotrichosis in Himachal Pradesh, India. Mycoses 2005; 48(1): 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Song Y, Li SS, Zhong SX, et al. Report of 457 sporotrichosis cases from Jilin province, northeast China, a serious endemic region. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2013; 27(3): 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharkey-Mathis PK, Kauffman CA, Graybill JR, et al. Treatment of sporotrichosis with itraconazole. NIAID mycoses study group. Am J Med 1993; 95(3): 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Conti Diaz IA, Civila E, Gezuele E, et al. Treatment of human cutaneous sporotrichosis with itraconazole. Mycoses 1992; 35(5–6): 153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Lima Barros MB, Schubach AO, de Vasconcellos Carvalhaes de Oliveira R, et al. Treatment of cutaneous sporotrichosis with itraconazole—study of 645 patients. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52(12): e200–e206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kauffman CA. Old and new therapies for sporotrichosis. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 21(4): 981–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kauffman CA, Bustamante B, Chapman SW, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of sporotrichosis: 2007 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45(10): 1255–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]