Abstract

Background

Skin involvement in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is common and can appear as an initial presentation of the disease or more commonly through its course.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 24-year-old male patient, previously diagnosed as having GPA, admitted with fever, hemoptysis, generalized hemorrhagic blisters associated with arthralgia, fatigue, myalgia, nasal crusting, and vertigo. Three weeks prior to admission, he developed erythematous papules on both elbows, and purpuric papules on both lower limbs. Histopathological examination revealed: interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (elbows) and foci of dermal hemorrhage, foci of interstitial histiocytes and zones of altered necrobiotic collagen (lower limbs) consistent with cutaneous lesions of GPA. Two weeks later, his rash progressed to widespread purpura associated with hemorrhagic blisters. Another biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls associated with perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils, nuclear dust and extravasated erythrocytes without an associated granulomatous inflammation or necrobiosis. The constellation of the results of the three biopsies together with clinical correlation pointed to a flare of GPA.

Conclusion

Skin involvement in GPA is quite common, and it can manifest in different forms in the same patient. Our patient developed three different skin pathologies within a short period of time.

Keywords: Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), Skin manifestations, Pathology, Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis, Leukocytoclastic vasculitis, Necrobiosis

Introduction

Cutaneous vasculitis can present in several forms, either a cutaneous component of systemic vasculitides, a skin-dominant or skin-limited expression of a systemic vasculitis; or a single-organ vasculitis of the skin that differs from recognized systemic vasculitides regarding clinical, laboratory, and histopathological features (e.g., nodular vasculitis) [1].

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) is an ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), affecting small- and medium- sized blood vessels. It is a multisystem disease characterized by necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and pauci-immune vasculitis [2].

According to a large multicenter study, skin affection in GPA is common and was found in 34% of patients. The most frequently encountered skin manifestations were petechiae or purpura (16%) followed by painful skin lesions (9.4%) and maculopapular rash (6.7%) [2].

According to the underlying histopathological changes, skin lesions in GPA can be classified as specific or non-specific. Specific lesions do not occur exclusively in GPA and can be seen in other vasculitic disorders; however, they show histopathological evidence of vasculitis or granuloma. Vasculitis can be in the form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis or granulomatous vasculitis. Granulomas can be in the form of necrobiotic palisading granulomas or abscesses surrounded by granulomatous inflammation. Classically, non-specific skin lesions do not show histopathological features of vasculitis or granuloma [3]. Extravascular granuloma can only be rarely detected in such lesions [4].

According to different reports, skin lesions may occur as the initial manifestation of the disease, however they mostly develop during the course of the disease [5], [6], [7], [8], [9].

Herein we present an unusual case of GPA who developed a disease flare presenting with three different types of skin lesions showing three different pathologies which to the best of our knowledge was not reported before.

Case report

A 24-year-old male patient, previously diagnosed with granulomatous polyangiitis (GPA), was admitted in the Internal Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, in August 2018 with fever, hemoptysis, generalized hemorrhagic blistering skin rash associated with arthralgia, fatigue, myalgia, nasal crusting, and vertigo.

A previous diagnosis of GPA was established 4 years earlier when the patient developed hemoptysis due to alveolar hemorrhage, confirmed by CT chest and bronchoscopic evaluation and lavage. He had nasal crustations and anti- PR3-ANCA was positive with no renal involvement. He received 3 pulses of methylprednisolone 1 gm for 3 days with 2 doses of 1000 mg rituximab (2 weeks apart), after which he was lost to follow-up.

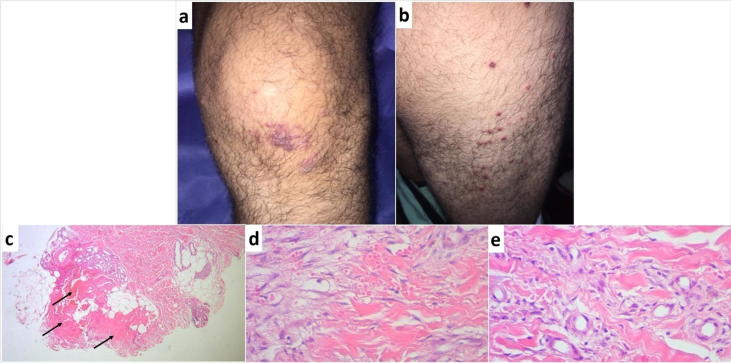

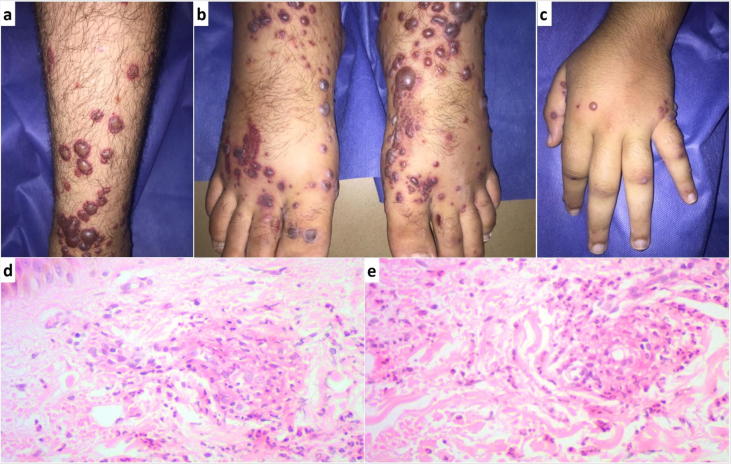

Three weeks prior to his recent admission, the patient (who had good general condition at that time) developed a skin eruption that started on his elbows followed by his lower limbs. Dermatological examination revealed erythematous papules on the elbows, some showing central umbilication, necrosis or crustations (Fig. 1a). The lower limbs lesions consisted of small dusky red purpuric papules (Fig. 2a and b). A punch skin biopsy was taken from both lesions. Histopathological examination of the elbow papules revealed: granulomatous infiltrate in the dermis composed of interstitial histiocytes infiltrating between altered necrobiotic collagen associated with interstitial mucin. Neutrophils and nuclear dust were also detected in addition to foci of necrobiosis surrounded by neutrophils (Fig. 1b–d). The findings were diagnostic of interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis), a known association of GPA. Histopathological examination of the lower limbs purpuric lesions revealed foci of dermal hemorrhage, foci of interstitial histiocytes and zones of altered necrobiotic collagen (Fig. 2c–e) which was also consistent with GPA. Two weeks later, the patient’s general condition deteriorated. He developed fever, hemoptysis, arthralgia and vertigo. His skin rash progressed to widespread purpuric lesions associated with hemorrhagic blisters (Fig. 3a–c). Another biopsy was taken from one of the hemorrhagic blisters and histopathological examination revealed typical features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis of the vessel walls and perivascular infiltrate of neutrophils, nuclear dust and extravasated erythrocytes. No granulomatous inflammation or necrobiosis was detected (Fig. 3d and e). The constellation of the results of the three biopsies together with clinical correlation concluded the diagnosis of a flare of GPA and the patient was admitted in the Internal Medicine Department.

Fig. 1.

Initial presentation (elbow papules), (a) Erythematous papules on the left elbow, some showing central umbilication, necrosis or crustations. (b–d) Photomicrographs depicting histopathological features of elbow papules; granulomatous inflammation with interstitial histiocytes (b, H&E original magnification X100), foci of necrobiosis surrounded by histiocytes (c, H&E original magnification X100) and interstitial mucin with neutrophils and nuclear dust (d, H&E original magnification X400).

Fig. 2.

Initial presentation (dusky purpuric papules over both lower limbs), (a and b) Small dusky red purpuric papules, (c–e) Photomicrographs depicting histopathological features of initial lower limb lesions; zones of necrobiotic collagen (black arrows) (c, H&E original magnification ×40), foci of dermal hemorrhage (d, H&E original magnification ×400) and interstitial histiocytes (e, H&E original magnification ×400).

Fig. 3.

Vasculitic flare, (a–c) Purpuric lesions with hemorrhagic blisters over the legs, feet and hands. (d and e) Photomicrographs depicting histopathological features of the flare lesions showing classic features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (fibrinoid necrosis of vessel walls associated with neutrophil infiltration, extravasation of erythrocytes and perivascular neutrophils (H&E original magnification ×400).

The patient had fever (38 °C). CT chest revealed cavitary lung lesions surrounded by ground-glass opacities. Laboratory investigations revealed leucocytosis (15,000/μL with shift to left) and elevated CRP (9.6 mg/dL). He had positive anti- PR3-ANCA by ELISA, negative ANA and normal urine analysis. Sputum culture showed E. coli growth. The patient received 3 daily pulses of methylprednisolone 1 gm/ day followed by prednisone 60 mg/daily without immunosuppressant. Levofloxacin 500 mg/day was given for 10 days according to sputum culture and sensitivity results. His general condition and his skin lesions showed marked improvement. Leucocytic count dropped to normal levels (8500/μL) and CRP to 0.6 mg/dL. After the control of infection, he received 2 doses of 1000 mg rituximab (2 weeks apart), and oral steroids were gradually withdrawn.

The patient was discharged and lost to follow-up.

Discussion

The three types of skin lesions encountered in our patient showed histopathological evidence of granuloma (first two biopsies) and vasculitis (third biopsy) which are the two cardinal histopathological features characterizing specific cutaneous lesions in GPA. They include palpable purpura, papulo-necrotic lesions, dermal/subcutaneous nodules, livedo reticularis, necrotic lesions and gangrene [4].

Palpable purpura affects mainly lower limbs and takes the form of purpuric macules, papules and ecchymotic plaques. As in our patient, severe cases may show widespread extension and hemorrhagic blisters. Ulcerations secondary to skin necrosis may also occur [3]. Vasculitis is the typical histopathological finding in the palpable purpuric lesions. An interesting finding in our patient was the lack of documented vasculitic changes in the small dusky red purpuric papules appearing at initial presentation on the patient's lower limbs and the presence instead of necrobiotic granulomatous changes associated with hemorrhage. This reflects the diversity and overlap in the clinicopathological appearance of skin lesions in GPA and highlights the importance of clinicopathological correlation in diagnosing these lesions.

The presence of papulo-necrotic lesions -also known as extravascular necrotizing granuloma of Winkelmann, Churg Strauss granuloma, palisaded neutrophilic and granulomatous dermatitis or interstitial granulomatous dermatitis- is common in GPA although they are not exclusively seen in GPA and can be associated with many systemic diseases. They typically develop around elbows and knees as papules that develop central necrosis and crustations as in our patient [10], [11].

Other specific skin lesions in GPA include dermal/subcutaneous tender nodules that arise mainly in the lower limbs. Livedo reticularis in GPA is usually associated with nodules or ulcers. Like other systemic vasculitides, acral gangrene can develop in GPA. Skin necrosis and painful ulcerations may precede systemic manifestations of GPA. Although they may present as pyoderma gangrenosum, they typically lack the typical raised undermined border. Involvement of the face and neck with pyoderma gangrenosum like lesions should raise the suspicion of GPA. The presence of anti- PR3-ANCA as well as the involvement of internal organs (mainly the lung) and the absence of a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate may help in excluding other pyoderma gangrenosum [12], [4], [13], [14], [15].

Non-specific skin manifestations include oral ulcers [4], gingivitis with exophytic hyperplasia, petechial spots and erythematous granular appearance (with or without loss of alveolar bone and teeth loosening) [16], non-specific skin ulcers (with no pathology of vasculitis or granulomas) [3], erythema nodosum-like lesions [17], xanthelasmas [4], pustules, vesicles [3], acneiform lesions [18] and chronic eyelid edema and infiltration [19].

Cutaneous lesions in GPA are diverse and their development may mark a relapse of the disease which is often associated with concomitant elevation of anti- PR3-ANCA [20] as in our patient. Accordingly, awareness of them is important for proper diagnosis and management..

We present a table that describes the main studies in Granulomatosis with polyangiitis describing cutaneous involvements (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies in Granulomatosis with polyangiitis describing cutaneous involvements.

| Reference | Number of GPA cases | Number of cases with skin involvement | Clinical types of skin lesions | Special remarks related to skin involvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [2] | 702 | 239 (34%) | Petechiae or purpura [113 cases] Painful skin lesions of any type [66 cases] Maculopapular rash [47 cases] Livedo reticularis [4 cases] Livedo racemose [2 cases] Non tender nodules [8 cases] Tender nodules [21 cases] Gangrene [11 cases] Splinter hemorrhage [11 cases] Ulcer [30 cases] Urticaria [5 cases] Pruritus [26 cases] Other [33 cases] |

|

| [18] | 52 | 19 (36.5%) | Palpable purpura Pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcerations Acneiform papules and pustules Folliculitis Churg-Strauss granulomas Nondescript papules, nodules and ulcerations Vasculitic and granulomatous lesions Petichial, purpuric and erythematous rashes |

Skin involvement was the initial manifestation of the disease in 7.7% of the 19 cases with skin involvement |

| [3] | 244 | 34 (14%) (complete data were available in 30 patients) |

Palpable purpura [14 cases] Pyoderma-like ulcers [8 cases] Papules [6 cases] Petechiae [3 cases] Nodules [4 cases] Superficial ulcerations [4 cases] Bullae [3 cases] Maculae and erythema [2 cases] |

Renal disease occurred in 80% of cases with skin involvement |

| [4] | 75 | 35 (46.7%) | Palpable purpura [26 cases] Oral ulcers [15 cases] Skin nodules [6 cases] Skin ulcers [5 cases] Necrotic papules [5 cases] Gingival hyperplasia [3 cases] Pustules [2 cases] Palpebral xanthoma [2 cases] Genital ulcer [1 case] Digital necrosis [1 case] Livedo reticularis [1 case] |

|

| [7] | 180 | 82 (46%) | Palpable purpura Ulcers Vesicles Papules Subcutaneous nodules |

In 13% of the cases, skin lesions occurred initially |

| [5] | 18 (with severe renal disease) | 12 (66.7%) | Vasculitis [9 cases] Diffuse non itchy macular or maculopapular erythematous rash [10 cases] Nodular lesions [1 case] |

Two cases developed skin lesions as the initial manifestation |

| [6] | 85 | 38 (45%) | Papules Vesicles Palpable purpura Ulcers Subcutaneous nodules |

Skin rash was the presenting sign in 11 (13%) of cases |

Conclusion

Our patient represented an unusual case of GPA with the development of three different specific skin pathologies. It highlights the importance of clinicopathological correlation in establishing a diagnosis of skin lesions arising in the context of a systemic vasculitic disorder.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Cairo University.

References

- 1.Sunderkötter C.H., Zelger B., Chen K.R. Nomenclature of cutaneous vasculitis: dermatologic addendum to the 2012 revised international Chapel Hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70:171–184. doi: 10.1002/art.40375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ChiesaFuxench Z., Micheletti R., Luqmani R., Watts R., Craven A., Merkel P.A. Cutaneous manifestations of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(suppl 10) doi: 10.1002/art.41310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daoud M.S., Gibson L.E., De Remee R.A., Specks U., El-Azhary R.A., Su W.P.D. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis: clinical, histopathologic and immunopathologic features of thirty patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:605–612. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francès C., Lê Thi Huong D., Piette J.C. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Dermatological manifestations in 75 cases with clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:861–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinching A.J., Lockwood C.M., Pussell B.A. Wegener’s granulomatosis: observations on 18 patients with severe renal disease. Q J Med. 1983;52:435–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauci A.S., Haynes B.F., Katz P., Wolff S.M. Wegener’s granulomatosis: prospective clinical and therapeutic experience with 85 patients for 21 years. Ann Intern Med. 1983;98:76–85. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-1-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoffman G.S., Kerr G.S., Leavitt R.Y. Wegener granulomatosis: an analysis of 158 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:488–498. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-116-6-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guillevin L., Cordier J.F., Lhote F. A prospective, multicenter, randomized trial comparing steroids and pulse cyclophosphamide versus steroids and oral cyclophosphamide in the treatment of generalized Wegener’s granulomatosis. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2187–2198. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lie J.T. Wegener’s granulomatosis: histological documentation of common and uncommon manifestations in 216 patients. Vasa. 1997;26:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finan M.C., Winkelmann R.K. The cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma (Churg–Strauss granuloma) and systemic disease: a review of 27 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983;62:142–158. doi: 10.1097/00005792-198305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huizenga T., Kado J.A., Pellicane B., Borovicka J., Mehregan D.R., Mehregan D.A. Interstitial granulomatous dermatitis and palisaded neutrophilic granulomatous dermatitis. Cutis. 2018;101:E19–E21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patten S.F., Tomecki K.J. Wegener’s granulomatosis: cutaneous and oral mucosal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:710–718. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70098-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kluger N., Francès C. Cutaneous vasculitis and their differential diagnoses. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(Suppl 2):S124–S138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Genovese G., Tavecchio S., Berti E., Rongioletti F., Marzano A.V. Pyoderma gangrenosum-like ulcerations in granulomatosis with polyangiitis: two cases and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2018;38:1139–1151. doi: 10.1007/s00296-018-4035-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moen B.H., Nystad T.W., Barrett T.M., Sandvik L.F. A boy in his teens with large ulcerations of the head and neck. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2019;139(7) doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.18.0647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manchanda Y., Tejasvi T., Handa R., Ramam M. Strawberry gingiva: a distinctive sign in Wegener’s granulomatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:335–337. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Comfere N.I., Macaron N.C., Gibson L.E. Cutaneous manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis: a clinicopathologic study of 17 patients and correlation to antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody status. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:739–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wright A.C., Gibson L.E., Davis D.M. Cutaneous manifestations of pediatric granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a clinicopathologic and immunopathologic analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:859–867. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gajic-Veljic M., Nikolic M., Peco-Antic A., Bogdanovic R., Andrejevic S., Bonaci-Nikolic B. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's granulomatosis) in children: report of three cases with cutaneous manifestations and literature review. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;(4):e37–e42. doi: 10.1111/pde.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mock M., Cerottini J.P., Derighetti M., Buxtorf K., Livio F., Panizzon R.G. Wegner's granulomatosis: description of a case where cutaneous involvement was correlated with elevation of the c-ANCA titer. Dermatology. 2001;202:347–349. doi: 10.1159/000051679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]