Abstract

Background

Some of the most debilitating symptoms of fibromyalgia (FM) include widespread chronic pain, sleep disturbances, chronic fatigue, anxiety, and depression. Yet, there is a lack of effective self-management exercise interventions capable of alleviating FM symptoms. The objective of this study is to examine the efficacy of a 10-week daily Qigong, a mind–body intervention program, on FM symptoms.

Methods

20 participants with FM were randomly assigned to Qigong (experimental) or sham-Qigong (control) groups, with participants blinded to the intervention allocation. The Qigong group practiced mild body movements synchronized with deep diaphragmatic breathing and meditation. The sham-Qigong group practiced only mild body movements. Both groups practiced the interventions two times per day at home, plus one weekly group practice session with a Qigong instructor. Primary outcomes were: pain changes measured by the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire, a visual analog scale for pain, pressure pain threshold measured by a dolorimeter. Secondary outcomes were: the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Quality of Life Scale.

Results

The experimental group experienced greater clinical improvements when compared to the control group on the mean score differences of pain, sleep quality, chronic fatigue, anxiety, depression, and fibromyalgia impact, all being statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Conclusion

Daily practice of Qigong appears to have a positive impact on the main fibromyalgia symptoms that is beyond group interaction.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03441997.

Keywords: Fibromyalgia, Widespread pain, Mind–body therapies, Qigong

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a chronic syndrome that was recognized as a clinical entity in 1990. The most prevalent and debilitating symptoms of FM are widespread chronic pain, chronic fatigue, and sleep disturbances.1, 2, 3 To date, the cause of FM is unknown. Recent guidelines for the treatment of FM developed by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR)4 focus on the management of FM symptoms. Suggested interventions for the management of FM include pharmacological therapies such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, neuropathic pain modulators, cognitive behavior therapy, and physical exercise such as moderate to high-intensity aerobic exercise. The guidelines published by the EULAR4 and the guidelines developed by the Canadian Pain Society and the Canadian Rheumatology5 recommend that available interventions should be tailored according to symptom intensity and patient preferences. With mind–body interventions gaining popularity in a variety of diseases and conditions, in the past ten years, the effectiveness of Qigong for the management of FM symptoms have been under investigation.6

Qigong is a type of mind–body self-management approach rooted in traditional Chinese medicine. To date, there are six randomized controlled trials reporting the effects of Qigong in individuals with FM7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and several other reports such as open-label studies, case reports and retrospective studies.6 In general, past clinical trials report positive results. However, the trials are noted with significant inconsistency in the design of the trials, different forms of Qigong, and different lengths of practice and dosage. Also, past trials compared the Qigong practice mostly against study participants on a wait-list that only received usual FM treatment or educational program treatment,7, 8, 10, 11 which could not control for the influence of social interaction or other research-related activities in the intervention group. It is also important to note that some studies used Qigong as a component of a multimodal intervention program,7, 11 making it impossible to determine the effectiveness of Qigong alone.

This study was part of a larger project divided into two phases: (1) a crossectional design phase to evaluate the cytokines responses due to high-intensity exercise and after the practice of mild exercise (Qigong) and (2) a randomized clinical trial phase to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of Qigong on clinical outcomes in patients with FM. The current study (phase 2) assessed the therapeutic efficacy of 10-weeks of Qigong practice on FM severity, widespread pain (WCP), chronic fatigue, sleep quality, depression/anxiety, and quality of life (QOL).

2. Methods and procedures

2.1. Trial registration

This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03441997 (Registered on February 2018).

2.2. 2.2Study design

This study was a double-blind (participants and assessors) pilot randomized controlled trial. The primary focus of this study was the clinical outcomes in FM participants after the practice of a 10-week home Qigong exercise two times per day with one weekly group practice with a Qigong instructor in the research laboratory.

2.3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants were females between 18 and 70 years of age, non-obese (body mass index ≤30) with the diagnosis of FM given by a physician according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 2010 criteria13 or the ACR 1990 criteria.14 Individuals were excluded if they reported in their clinical history any of the following: regular use of opioids defined as any opioid prescription for at least 60 days within six months period; major depressive disorders; autoimmune, endocrine disorders or chronic inflammatory illness; abuse of alcohol, benzodiazepines, or other drugs; severe psychiatric illness; active cardiovascular, pulmonary illness; current systemic infection; active cancer; severe sleep apnea (as classified by the Apnea–Hypopnea Index); pregnancy or breastfeeding. Participants on a stable dosage of medication for sleep, pain, or mild depression were not excluded. Eligible participants were asked not to plan on starting any FM treatments such as biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, acupuncture, yoga, tai chi, tender point injections, and anesthetic or narcotic patches during the study period. Participants were instructed to maintain their regular physical activities, but not to initiate any new physical activity and not to change medications during the duration of the study.

Potential FM participants were identified using the Healthcare Enterprise Repository for Ontological Narration (HERON) provided by the University of Kansas Medical Center.15

2.4. Group allocation and blinding process

After signing the consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board, the participants were randomly assigned to either experimental group (Qigong) or control group (sham-Qigong) by a computer-generated 1:1 (e.g., 0 or 1) simple randomization table created in Microsoft Excel; the randomization was conducted by an assistant researcher who was not involved in the data collection or analysis. The informed consent stated that the study aimed to compare the outcomes of two mild exercise programs without using the words “control/sham” and “intervention/experimental.” Also, terms such as “Qigong” or “meditation” were not used to prevent the control group from potential exposure to the experimental intervention. Participants were also advised to avoid researching relevant information about the study content either online or from any other external sources. Finally, all activities were separated between the experimental and control groups. Researchers involved in the data analysis were blinded to participants’ group assignments. All data were coded before releasing for analysis.

2.5. Study procedures

On the first visit day, the informed consent and baseline evaluation were conducted. Repeated measurements were conducted at the end-intervention evaluation after 10 weeks of intervention practice.

After the baseline measurements, the participants in the experimental and control groups learned the exercises from two instructors in weekly group training sessions for two weeks. After the training sessions, the participants were oriented to perform the exercises two times per day at home (morning and evening) for the remaining days of the week. Both groups were asked to come to the Neuromuscular Research Laboratory one time per week for a group practice. The weekly exercise sessions in the laboratory took approximately 45 minutes; the first 20 minutes were reserved for participants questions about the exercise interventions and general questions about FM, the remaining 25 minutes was devoted to the intervention practice with the instructor. Counting from the first week of training the interventions lasted for ten weeks. All participants were required to keep an exercise diary that was used to track their exercise compliance at home. In addition, participants were instructed to write down any safety-related issues or concerns due to the daily practice of Qigong exercise at home. Participants were asked to report to the principal investigator or research assistant immediately if an adverse event occurred due to the exercise.

2.6. Outcome measures

The primary outcome measurement was changes in pain intensity measured by the Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SMPQ),16 a visual analog scale (VAS) of pain from 0 to 10 and the evoked pressure pain threshold (PPT). In the current study, PPT was measured in the left and right side of upper neck muscles, middle trapezius, and posterior forearm. An average score was calculated from the six measured sites. The secondary outcome measures were FM impact assessed by the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionaire (FIQR),17 sleep quality assessed by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI),18 fatigue level assessed by the VAS for fatigue included in the FIQR, QOL evaluated by the Quality of Life Scale (QOLS),19 depression and anxiety evaluated by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).20

2.7. Differences from original registration

The current manuscript reports the findings from the second phase of the study. The data collected from the first phase (cytokines responses due to high-intensity exercise and after the practice of Qigong) is currently under analyses. The protocol used for the second phase reported in the current manuscript underwent updates from the original registration. The intervention was extended from 8 weeks to 10 weeks and the following outcomes measurements were added into the protocol: VAS, SMPQ and HADS.

2.8. Intervention

2.8.1. Qigong

The type of Qigong used in this study is called “six healing sounds”, consisting of the three elements – deep diaphragmatic breathing, mild body movements, and meditation, along with uttering six healing sounds. A complete description of the six healing sounds Qigong program can be found in a protocol study published by our research team.21 An experienced instructor trained a graduate research assistant. Both of them took part in the training of the participants. The research group participants were trained on how to control deep breathing using the diaphragmatic breathing technique while reciting each of the “healing sounds.” The breathing technique was synchronized with slow and smooth upper body movements that were performed according to each “healing sound.” The participants were also asked to clear their minds while in a meditated status by concentrating on the diaphragmatic contraction and expansion. Each exercise practice took approximately 25 minutes.

2.8.2. Sham qigong

The participants in the sham-Qigong (control) group were trained in the same body movements as the Qigong (experimental) group. However, healing sounds combined with diaphragmatic breathing and meditation were not taught. Each exercise practice also took approximately 25 minutes.

2.9. Statistical analyses

WCP score comparisons were made using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA); upon significant changes in WCP was identified, each outcome measure was analyzed with independent t-test. Sleep quality, chronic fatigue, FMI, depression, anxiety, and QOL mean changes from baseline to post-intervention were compared with independent t-tests. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to examine the impact on changes in clinical outcomes after the intervention by any covariate that showed significant difference at baseline between the two groups. The analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 25. A significance level was set a priori at p < 0.05.

3. Results

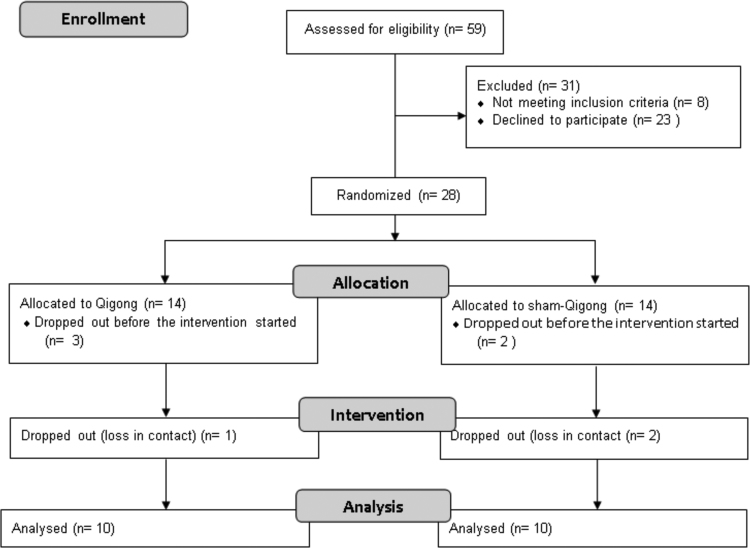

It was estimated that 40 participants with FM would be enrolled in this study. However, after a year of recruitment, only 28 participants fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. In total, 278 females with the diagnosis of FM were contacted via email by a research assistant. Fifty-five individuals replied to the email message, demonstrating an interest in participating and were contacted via telephone by a research assistant who performed screening to confirm eligibility. Twenty-four individuals were confirmed as meeting the inclusion/exclusion criteria over the phone. An additional four participants were referred to the study by a rheumatologist. In total, 28 participants completed the baseline assessments (Fig. 1). Eight participants dropped out of the study (four from each group). Five participants dropped out after the baseline measurements, but before the exercise programs started due to time conflict. Three participants dropped out after the exercise programs started (one from the experimental group and two from the control group), due to loss in contact.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

Both interventions, Qigong and sham-Qigong were well-tolerated by all the participants; none of the participants reported increasing symptoms due to the interventions or any other adverse events. Analyses of the exercise diaries showed that the intervention group had a rate of 72% of compliance to home daily Qigong exercise, whereas the control group had a compliance rate of 79%. No changes in medication were reported during the intervention period.

Ten participants in each group completed the 10-week exercise program. There was a statistically significant difference in the mean age between groups: experimental group (42.6 ± 10.7 years) and control group (56.1 ± 12.3 years) (p < 0.05). There was no statistical difference in FM duration, and FM intensity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Groups’ Characteristics

| Experimental (n = 10) | Control (n = 10) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 42.6 ± 10.7 | 56.1 ± 12.3 | 0.05 |

| Duration of FM, years | 12.5 ± 4.7 | 12.6 ± 5.0 | 0.9 |

| FM intensity | Moderate, 52.1 ± 18.5 | Moderate, 57.6 ± 16.7 | 0.5 |

The values for age and duration of FM are represented in mean ± standard deviation. The classification for FM severity was obtained according to the Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR). FM – fibromyalgia.

The experimental group experienced greater improvements in the primary outcome measurements. The mean scores of changes in the three pain measurements pre and post intervention analyzed by MANOVA were statistically significant at p < 0.05. Post hoc analysis identified a significant difference in the changes of the SMPQ scores (p < .01) and VAS scores (p < .05), while the changes in PPT scores were close to significance (p = 0.06) (Table 2). For the secondary outcome measurements the experimental group presented significant improvements in fatigue (p < 0.05), depression (p < 0.05), anxiety (p < 0.05), sleep quality (p < 0.01), and FM impact scores (p < 0.01). The control group experienced significantly better improvement than the intervention group in the changes in the total score of QOL (p < 0.05). Table 2 reports baseline and post intervention mean for each outcome measurements followed by statistical reports and effect size.

Table 2.

Between-group Comparison of Changes from Baseline to 10-Week Post Intervention

| Baseline |

10 weeks |

p value | Cohen's d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental (n = 10) | Control (n = 10) | Experimental (n = 10) | Control (n = 10) | |||

| Pain | ||||||

| SMPQ | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 7 ± 1.8 | 3.6 ± 2.3 | 6.4 ± 1.9 | 0.01** | 1.26 |

| PPT | 572 ± 173 | 747 ± 181 | 782 ± 196 | 750 ± 452 | 0.06 | 0.74 |

| VAS | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 7 ± 1.5 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 6.8 ± 2.1 | 0.05* | 1.58 |

| Sleep quality | 9.7 ± 2.5 | 12.2 ± 4.2 | 6 ± 3.3 | 11.3 ± 4.9 | 0.01** | 1.6 |

| Fatigue | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 7.1 ± 2 | 4.3 ± 2.8 | 6.4 ± 2.6 | 0.05* | 0.8 |

| FM impact | 52.1 ± 18.5 | 57.6 ± 16.7 | 32.5 ± 19.6 | 50.5 ± 21.2 | 0.01** | 1.17 |

| Depression | 7.4 ± 3.4 | 7.3 ± 4.9 | 4.2 ± 3.4 | 6.5 ± 4.6 | 0.05* | 0.84 |

| Anxiety | 11.4 ± 3.7 | 7.8 ± 5.5 | 7.4 ± 3.2 | 6.3 ± 4.4 | 0.05* | 0.89 |

| QOL | 76.1 ± 16.5 | 69.8 ± 21.1 | 79.4 ± 15.4 | 84.6 ± 8.8 | 0.05*• | 0.81 |

The values are shown in mean ± standard deviation.

Indicates statistical significance at P < 0.01.

Indicates statistical significance at P < 0.05

• Indicates that the control group presented superior improvement than the experimental group.

FM, fibromyalgia; PPT, pressure pain threshold; QOL, quality of life; SMPQ, Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire; VAS, visual analog scale.

ANCOVA analyses indicated that age had no significant influence on any of the dependent variables. However, it was observed that the influence of age on sleep quality presented a trend towards significance (p = 0.07).

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that the daily practice of six-healing sounds Qigong intervention may be a feasible home-based self-management intervention for individuals with FM. The participants reported no adverse events due to Qigong or sham-Qigong, and all the participants were able to memorize the exercise sequence within two weeks of practice.

The results of this study show that the 10-week Qigong exercise leads to improvements in most notorious FM symptoms, including widespread pain, chronic fatigue, sleep disturbance, FM disease intensity, depression, and anxiety. The results reported in this study are in accordance with previous studies.8, 9, 10

The mild body movements alone (sham-Qigong exercise) practiced by the control group were not enough to promote significant improvement in the majority of symptoms, except a modest decrease in FM disease intensity.

The discrepancy in the outcomes between improvement in symptoms and quality of life may be related to the small sample size and the tools used in the study to assess QOL. Also, the finding may be explained by the positive group interaction that was observed among the participants in the control group during the study period.

A possible underlying mechanism that mediated the symptom improvements observed in the experimental group might be the immune state regulation through Qigong including C-reactive protein (CRP),22 interleukin-6 (IL-6). Another possible biological pathway related to Qigong exercise may be related to its influence on hormonal stress levels. Besides the possible improvements in stress responses due to the optimization of the HPA axis promoted by Qigong, this intervention might also play a role in modulating the activity of the autonomic nervous system.23, 24 Optimized autonomic nervous system can downregulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, therefore reducing levels of pain.

The current study is not free of limitations. One of the most significant limitations of the current study is the sample size (10 participants in each group), possible exposure of mind–body exercises in the media and online sources and the use of subjective outcome measures. Another possible limitation was the difference in age encountered between groups. ANCOVA analysis indicated that differences in age likely favored improvements in sleep quality in the intervention group. Lastly, the current study did not conduct a follow-up assessment.

In conclusion, the findings of this study suggest that the combination of the three components that constitute Qigong exercise (deep diaphragmatic breathing mild body movements, and meditation) may have a therapeutic effect on FM symptoms. However, further rigours large sample-sized studies are needed to confirm the efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Michael Steinbacher for helping with recruitment and data entry. We also would like to thank all the participants for their time commitment to this project.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conceptualization: CS and WL; methodology: CS, WL, and SM; validation: CS, WL, and SM; data analysis: CS, SL, and WL; investigation: CS, SM, and TP; resources: CS and TP; data curation: CS and TP; writing and revisions: CS, SM, TP, IS, YC, SL, and WL; supervision: WL; project administration: CS and WL.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Kansas Medical Center (STUDY00141263). Written consent to participate in this study was obtained from each participant.

Data availability

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Mannerkorpi K., Burckhardt C.S., Bjelle A. Physical performance characteristics of women with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7:123–129. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F., Clauw D.J., Fitzcharles M.A., Goldenberg D.L., Katz R.S., Mease P. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:600–610. doi: 10.1002/acr.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe F., Smythe H.A., Yunus M.B., Bennett R.M., Bombardier C., Goldenberg D.L. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcantara Montero A., Sanchez Carnerero C.I. [EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia] Semergen. 2017;43:472–473. doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fitzcharles M.A., Ste-Marie P.A., Goldenberg D.L., Pereira J.X., Abbey S., Choiniere M. 2012 Canadian Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of fibromyalgia syndrome: executive summary. Pain Res Manag. 2013;18:119–126. doi: 10.1155/2013/918216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sawynok J., Lynch M.E. Qigong and fibromyalgia circa 2017. Medicines (Basel) 2017;4 doi: 10.3390/medicines4020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Astin J.A., Berman B.M., Bausell B., Lee W.L., Hochberg M., Forys K.L. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation plus Qigong movement therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2257–2262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haak T., Scott B. The effect of Qigong on fibromyalgia (FMS): a controlled randomized study. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:625–633. doi: 10.1080/09638280701400540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu W., Zahner L., Cornell M., Le T., Ratner J., Wang Y. Benefit of qigong exercise in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Int J Neurosci. 2012;122:657–664. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.707713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch M., Sawynok J., Hiew C., Marcon D. A randomized controlled trial of qigong for fibromyalgia. Arthrit Res Therapy. 2012;14:R178. doi: 10.1186/ar3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mannerkorpi K., Arndorw M. Efficacy and feasibility of a combination of body awareness therapy and qigong in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36:279–281. doi: 10.1080/16501970410031912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maddali Bongi S., Del Rosso A., Di Felice C., Cala M., Giambalvo Dal Ben G. Resseguier method and Qi Gong sequentially integrated in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(Suppl 74):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe F., Clauw D.J., Fitzcharles M.A., Goldenberg D.L., Hauser W., Katz R.S. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:1113–1122. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe F. Fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1990;16:681–698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waitman L.R., Warren J.J., Manos E.L., Connolly D.W. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings AMIA Symposium, 2011. 2011. Expressing observations from electronic medical record flowsheets in an i2b2 based clinical data repository to support research and quality improvement; pp. 1454–1463. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz J., Melzack R. Measurement of pain. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:231–252. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70381-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett R.M., Friend R., Jones K.D., Ward R., Han B.K., Ross R.L. The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthrit Res Therapy. 2009;11:R120. doi: 10.1186/ar2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buysse D.J., Reynolds C.F., 3rd, Monk T.H., Berman S.R., Kupfer D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flanagan J.C. A research approach to improving our quality of life. Am Psychol. 1978;33:138–147. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon S., Sarmento C.V.M., Smirnova I.V., Colgrove Y., Lyons K.E., Lai S.M. Effects of Qigong exercise on non-motor symptoms and inflammatory status in parkinson's disease: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Medicines (Basel) 2019;6 doi: 10.3390/medicines6010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan N., Irwin M.R., Chung M., Wang C. The effects of mind–body therapies on the immune system: meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qigong Sawynok J. Parasympathetic function and fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia: Open Access. 2016;1 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M.S., Huh H.J., Kim B.G., Ryu H., Lee H.S., Kim J.M. Effects of Qi-training on heart rate variability. Am J Chin Med. 2002;30:463–470. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X02000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.