Abstract

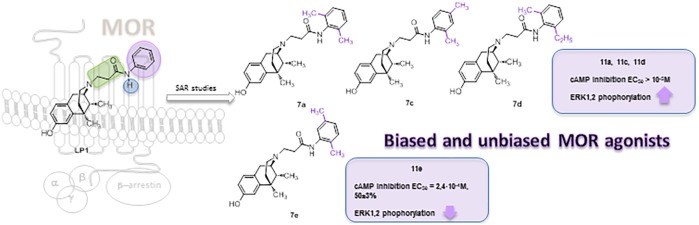

Modifications at the basic nitrogen of the benzomorphan scaffold allowed the development of compounds able to segregate physiological responses downstream of the receptor signaling, opening new possibilities in opioid drug development. Alkylation of the phenyl ring in the N-substituent of the MOR-agonist/DOR-antagonist LP1 resulted in retention of MOR affinity. Moreover, derivatives 7a, 7c, and 7d were biased MOR agonists toward ERK1,2 activity stimulation, whereas derivative 7e was a low potency MOR agonist on adenylate cyclase inhibition. They were further screened in the mouse tail flick test and PGE2-induced hyperalgesia and drug-induced gastrointestinal transit.

Keywords: Multitarget, dual-target, pain, SAR, benzomorphan, opioid

During the past decade efforts were made to develop effective multitarget opioid ligands as an alternative strategy to overcome the typical side effects associated with opioid selective agonists.1−3 For instance, a valid analgesic effect with lower propensity to produce tolerance and physical dependence was reported for both dual MOR/DOR agonist4−6 and MOR agonist/DOR antagonist ligands given in persistent pain models.7−9

Recently, the concept of biased agonists,10 able to differentially activate GPCR downstream pathways, became a new approach in the design of novel drug candidates. It was reported that opioid compounds promoting G-protein signaling produce analgesia, while β-arrestin recruitment is responsible for opioid side effects such as constipation.11−13

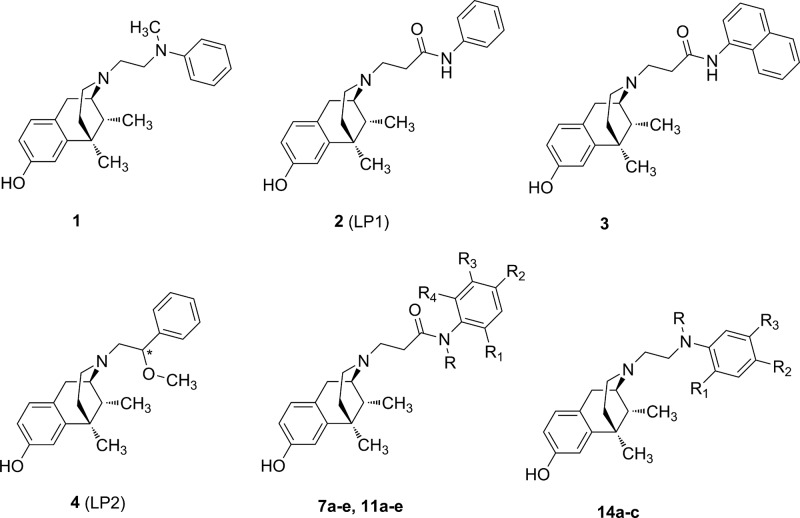

Benzomorphan nucleus represents a versatile template14,15 for the development of a specific functional profile by modifying N-substituent or 8-OH group. In this context, the introduction of a tertiary N-methyl-N-phenylethylamino group as N-substituent conferred a MOR agonist profile in vitro and in vivo (1, Figure 1).16 The replacement of the N-ethylamino spacer with the N-acetamido one was detrimental for MOR, DOR, and KOR recognition,17 while an N-propanamido spacer improved the opioid binding profile. In particular, LP1 (2, Figure 1), with an N-phenylpropanamido substituent, resulted in vitro and in vivo a potent MOR agonist/DOR antagonist18 able to counteract nociceptive pain and behavioral signs of persistent pain with low tolerance-inducing capability.19,20 The phenyl replacement with the bulkier N-naphthyl ring (3, Figure 1) switched the MOR efficacy profile from agonism to antagonism.21 Analogously, the increased steric hindrance of the aromatic moiety with an indoline, tetrahydroquinoline or diphenylamine group affected the shift from MOR agonism to antagonism.22 More recently, a dual MOR/DOR agonist, endowed of a significant long-lasting antinociceptive effect,23−25 was developed through the introduction of the short and flexible 2R/S-methoxy ethyl spacer as N-substituent (LP2 4, Figure 1). Moreover, the 2S diastereoisomer of LP2 was found to be a potent G-protein biased MOR/DOR agonist with a 3-times lower ED50 value.26

Figure 1.

Benzomorphan-based compound structures.

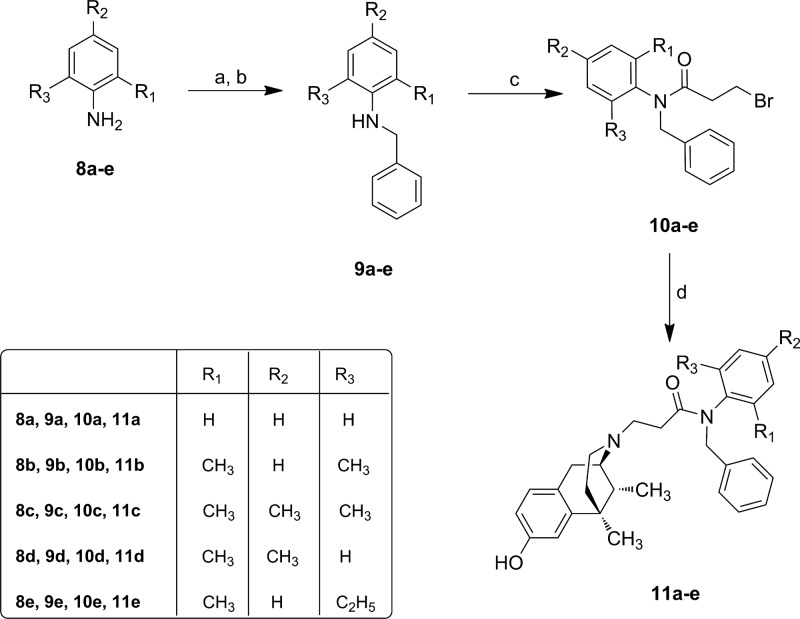

Since minor structural modifications often result in significant changes in the pharmacological profile of opioid ligands, we expanded our SAR studies by the synthesis of LP1 derivatives 7a–e, variously alkylated at the phenyl ring of the N-propanamido substituent, and 11a–e, featured also by a tertiary N-propanamido substituent. Finally, derivatives 14a–c, bearing a secondary or tertiary N-ethylamino spacer, were synthesized (Figure 1).

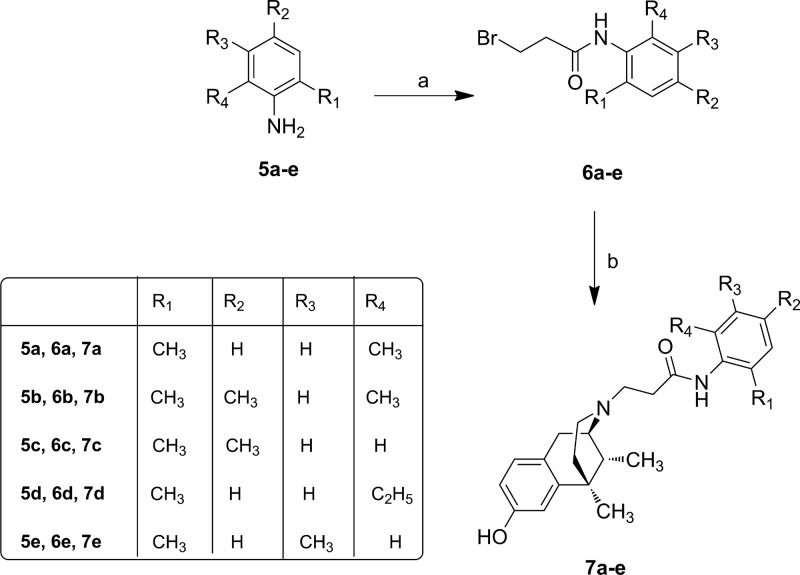

According to the previously reported method,17,28 we prepared derivatives 7a–e, 11a–e and 14a–c as reported in Schemes 1–3. After cis-(±)-N-normetazocine resolution,27 the target compounds 7a–e were obtained by alkylation of cis-(−)-(1R,5R,9R)-N-normetazocine with the respective amides 6a–e (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of N-Substituted Normetazocine Derivatives 7a–e.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 3-bromopropionyl chloride (1.5 equiv), 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) (0.47 equiv), dry THF, rt, 3h; (b) (−)-cis-(1R,5R,9R)-N-normetazocine (1 equiv), NaHCO3 (1.5 equiv), KI, DMF, 65 °C, 20 h.

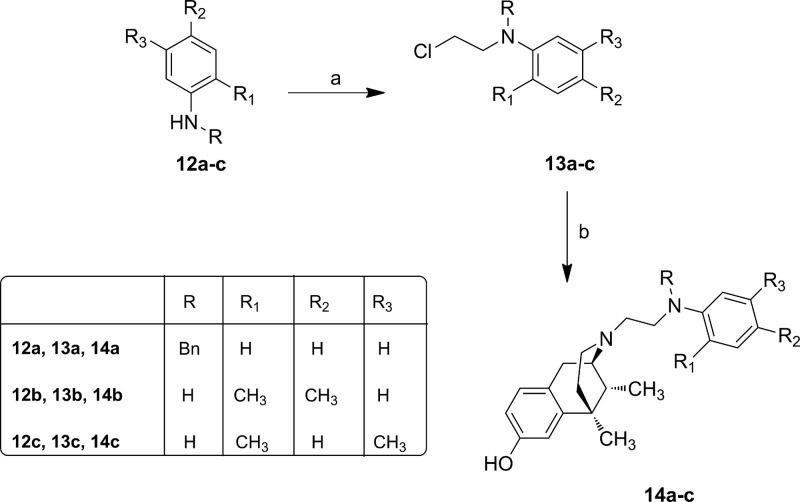

Scheme 3. Synthesis of N-Substituted Normetazocine Derivatives 14a–c.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1-bromo-2-chloroethane (0.3 equiv), CH3CN, 110 °C in sealed tube, 10 min; (b) (−)-cis-(1R,5R,9R)-N-normetazocine (1 equiv), NaHCO3 (1.5 equiv), KI, DMF, 50 °C, 12 h.

N-Benzyl anilines 9a–e, obtained by reductive amination with NaBH4, were acylated with 3-bromopropionyl chloride to obtain the respective amides 10a–e. Derivatives 11a–e were prepared according to the synthetic route shown in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of N-Substituted Normetazocine Derivatives 11a–e.

Reagents and conditions: (a) benzaldehyde (1 equiv), MeOH, reflux, 3 h; (b) NaBH4 (0.5 M solution in EtOH) reflux, 6 h; (c) 3-bromopropionyl chloride (1.5 equiv), 4-(dimethylamino)pyridine (DMAP) (0.47 equiv), dry THF, rt, 3h; (d) (−)-cis-(1R,5R,9R)-N-normetazocine (1 equiv), NaHCO3 (1.5 equiv), KI, DMF, 65 °C, 20 h.

The N-(2-chloroethyl)anilines 13a–c were obtained by alkylation with 1-bromo-2-chloroethane.29 Then, the next step to get target derivatives 14a–c was carried out as reported in Scheme 3. All newly synthesized compounds were characterized by IR, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, MS and elemental analysis.

To investigate the SAR of synthesized novel derivatives, their binding and efficacy profile at MOR, DOR, and KOR was explored. Binding at MOR, DOR, and KOR was evaluated by competitive displacement of [3H]DAMGO, [3H]DPDPE, and [3H]U69,593, respectively.30 Ki values of derivatives 7a–e, 11a–e, and 14a–c, calculated using nonlinear regression analysis (GraphPad Prism), are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Opioid Receptor Binding Affinity of LP1 (2) Derivatives 7a–e, 11a–e, and 14a–c.

| Ki (nM) ± SEMa,b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cmp | R | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | MOR | DOR | KOR |

| 7a | H | CH3 | H | H | CH3 | 7.4 ± 0.75 | 277 ± 12 | 252 ± 10 |

| 7b | H | CH3 | CH3 | H | CH3 | 43.7 ± 2 | >2,000 | 313 ± 15 |

| 7c | H | CH3 | CH3 | H | H | 20.8 ± 1 | 474 ± 20 | 340 ± 13 |

| 7d | H | CH3 | H | H | C2H5 | 14.9 ± 0.92 | 198 ± 8 | 320 ± 11 |

| 7e | H | CH3 | H | CH3 | H | 7.9 ± 0.65 | 478 ± 22 | 480 ± 22 |

| 11a | Bn | H | H | H | H | 606 ± 34 | >5,000 | >5,000 |

| 11b | Bn | CH3 | H | H | CH3 | 400 ± 24 | >5,000 | >3,000 |

| 11c | Bn | CH3 | CH3 | H | CH3 | 504 ± 27 | >5,000 | 444 ± 24 |

| 11d | Bn | CH3 | CH3 | H | H | 165 ± 7 | >5,000 | >2,000 |

| 11e | Bn | CH3 | H | H | C2H5 | 1,540 ± 59 | >5,000 | 151 ± 6 |

| 14a | Bn | H | H | H | H | 244 ± 12 | >1,000 | >3,000 |

| 14b | H | CH3 | CH3 | H | H | 129 ± 10 | >5,000 | >1,000 |

| 14c | H | CH3 | H | CH3 | H | 182 ± 13 | >5,000 | >2,000 |

| 1c | 6.1 ± 0.50 | 147 ± 5.70 | 31 ± 1.30 | |||||

| 2 (LP1)d | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 29 ± 1.00 | 110 ± 6.00 | |||||

| DAMGO | 0.90 ± 0.04 | - | - | |||||

| Naltrindole | - | 0.83 ± 0.04 | - | |||||

| U50,488 | - | - | 0.27 ± 0.03 | |||||

The synthesized derivatives showed a broad range of binding affinity for MOR (Ki = 7.4–1,540 nM) and low or no affinity for DOR and KOR. Derivatives 7a and 7e, having methyl groups in positions 2′,6’ and 2′,5′, respectively, possessed the highest MOR affinity, followed by derivatives 7b, 7d, and 7c, having slightly less affinity for this receptor. A third methyl group in position 4′ (7b), as well as an ethyl group in position 6′ (7d), reduced MOR affinity by 6- and 2-times compared to 7a and 7e. The dimethyl alkylation in positions 2′ and 4′ (7c) resulted in a worse MOR binding profile. Thus, methylation in ortho and meta is well tolerated while the para-methylation was unfavorable. In MOR-ligand interaction the negative influence of para substitution, with both electron-withdrawing or electron-donor groups, was outlined.22 A worse DOR and KOR binding profile was recorded for derivatives 7a–e. Indeed, in comparison to LP1 their DOR and KOR affinities were from 7- to 69-times and from 7- to 61-times lower, respectively. The introduction of a benzyl pendant at the amidic nitrogen (11a) and the simultaneous phenyl ring methylation (11b–e) was detrimental for opioid binding affinity, mainly at DOR and KOR (Table 1). Such modifications hindered the ligands to adopt a compatible ligand–receptor conformation. Derivatives 14a–c, featured by an N-ethylamino spacer, showed MOR affinity higher than derivatives 11a–e and lower than derivatives 7a–e. The steric hindrance at the amine nitrogen in derivative 14a resulted in a dramatic loss of opioid receptor affinity, mainly at MOR, with respect to compound 1 (KiMOR = 6.1 nM), featured by a tertiary N-methyl-N-phenylethylamino group.

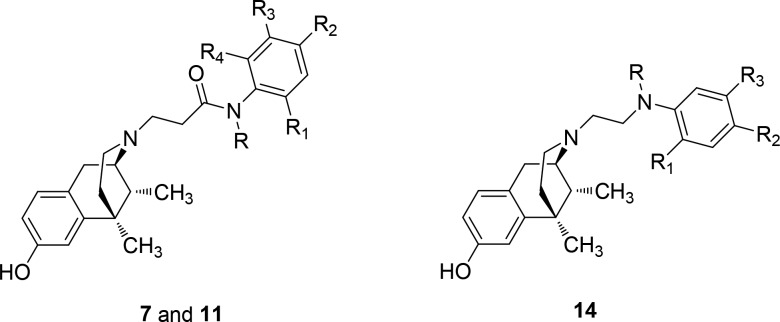

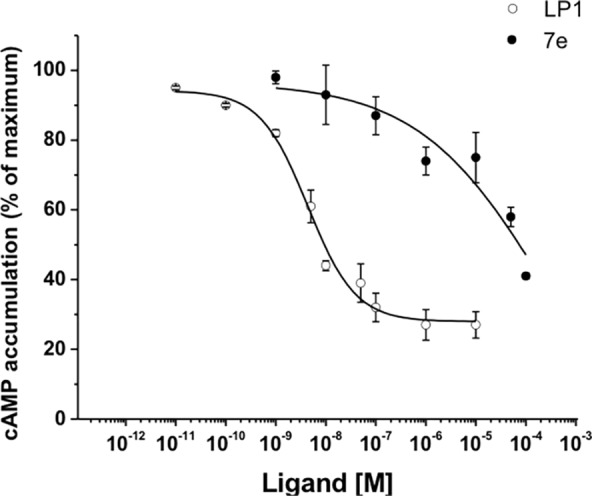

To examine the functional significance of derivatives 7a–e, displaying the best MOR binding profile, we tested their ability to affect agonist-mediated AC inhibition. Opioid receptors signal through Gi/Go proteins to inhibit AC,31−34 which is known to be one of their major pathways to induce analgesia.12 For that reason, HEK293 cells stably expressing the MOR were treated with increasing concentrations of derivatives 7a–e, and the levels of forskolin-stimulated AC activity were tested. Derivatives 7a–7d were unable to inhibit AC even at high concentrations up to 10–5 M (data not shown). Treatment of HEK293 cells with compound 7e resulted with 50 ± 3% inhibition of cAMP accumulation at a concentration of 10 μΜ (Figure 2). However, this effect was much lower than that detected with LP1 (Figure 2). These results suggest that derivative 7e could be considered as an effective MOR agonist with low potency on AC inhibition. To further identify whether derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e behave as MOR agonists, we measured alterations of ERK1,2 phosphorylation mediated by these derivatives upon MOR activation. It was previously demonstrated that opioid receptors stimulate ERK1,2 via a pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi/o-protein signaling mechanism32−34 and regulate additional effectors by interacting with other scaffolding proteins.35 In addition, it is well-known that signaling of opioid receptors through a ß-arrestin pathway leads to ERK1,2 activation.36 Serum-starved HEK293 cells expressing stably the MOR were challenged with derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e with different time intervals ranging from 5 to 15 min. As shown in Figure 3, Western blotting with a specific phospho-ERK1,2 antibody revealed an increase in ERK1,2 phosphorylation reaching a peak within 5 min administration for tested derivatives, which decreased after 15 min of compound exposure. The same pattern of increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation was also shown for LP1. However, the levels of ERK1,2 phosphorylation mediated by derivative 7e retain even after 15 min of receptor stimulation. These results suggest that 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e act as potent MOR agonists with derivatives 7a, 7c, and 7d exerting biased agonist properties toward ERK1,2 activity stimulation.

Figure 2.

Effect of derivative 7e and LP1 on MOR-mediated cAMP accumulation. The inhibition of cAMP accumulation was measured as described in the Supporting Information in HEK293 cells stably expressing the MOR in the presence of various concentrations of LP1 and 7e, in response to treatment with 50 μΜ forskolin. The IC50 values of LP1 and 7e are 4.8 × 10–9 ± 0.5 M and 2.4 × 10–4 ± 0.83 M, respectively. Data represent as cAMP accumulation (% of maximum) and are the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations from three independent experiments.

Figure 3.

Effect of derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e on ERK1,2 phosphorylation mediated upon MOR activation. Stably transformed HEK293 cells expressing the MOR were challenged with 1 μΜ of derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e for 5, 10, and 15 min, and cell lysates were resolved in SDS-PAGE (10%). The ERK1,2 phosphorylation mediated by DAMGO and LP1 (1 μΜ) after 5 min exposure was used as positive control. Phosphorylation of ERK1,2 was abolished upon pretreatment of the cells with naloxone (10 μΜ, 30 min), prior to 5 min DAMGO administration (negative control). The phosphorylated-ERK1,2 was visualized by immunoblotting with a phosphor-ERK1,2 (upper panel). Equal loading was verified by stripping and reprobing the PVDF membrane with a specific α-tubulin antibody (lower panel). Results are representative of three independent experiments.

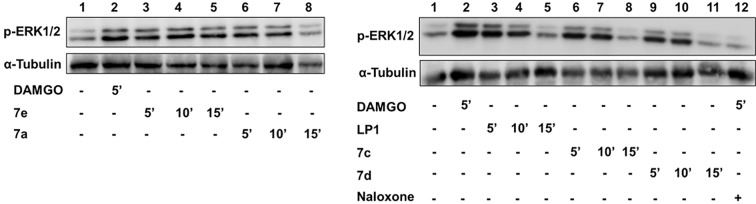

To determine if an in vitro biased and unbiased G-protein profile could reflect what is happening in animal pain models, derivatives 7a and 7e were further screened in the mouse-tail flick test. 7a and 7e, in a dose range from 2.5 up to 7.5 mg/kg i.p., did not significantly modify TFLs, during the entire time of observation (90 min, Figure 4 panel A and B, respectively) compared to the group of mice treated with saline (p > 0.05 vs saline-treated mice).

Figure 4.

Time-course (min) of derivatives 7a and 7e-induced antinociceptive effect measured by tail flick test (panel A and B, respectively). Results are expressed in seconds (s). Data are means ± SEM from 6 to 8 mice. *P < 0.05 vs saline-treated mice.

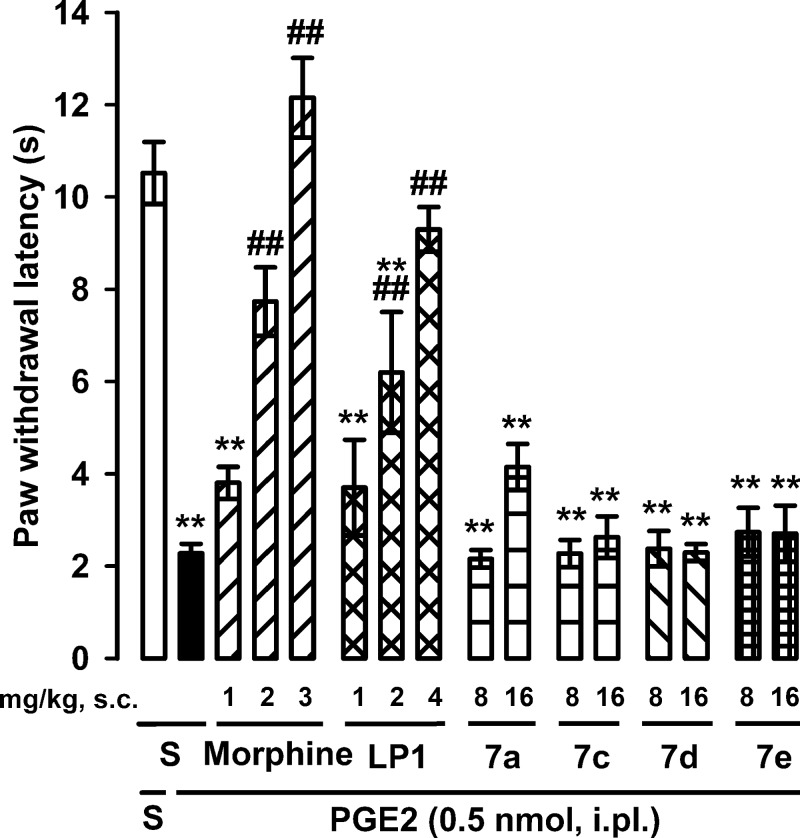

Considering that PGE2-induced hyperalgesia is well-known to be triggered by cAMP accumulation and the consequent protein kinase A activation,37 we selected this assay as a suitable index of the behavioral effects of the derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e through cAMP inhibition. The administration of PGE2 induced a marked decrease in the withdrawal latency of the injected paw to heat stimulation, in comparison to saline-injected controls, denoting the development of thermal hyperalgesia. There were no statistically significant differences between the values obtained in the paw contralateral to PGE2 or saline (data not shown). Both morphine (1–3 mg/kg, s.c.) and LP1 (1–4 mg/kg, s.c.) induced a dose-dependent increase in paw withdrawal latency in PGE2-treated mice, reaching values similar to control animals (i.e., a full antihyperalgesic effect) (Figure 5) at the highest doses tested. In contradiction, the administration of 7a, 7c, 7d, or 7e (8–16 mg/kg, s.c.) did not induce any significant antihyperalgesic effect (Figure 5). These results are in agreement with the inhibition of cAMP accumulation by morphine and LP1 and the absence of any effect detected by 7a, 7c, 7d, or 7e in the same experiments.

Figure 5.

Effects of morphine, LP1, and derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e on PGE2-induced heat hyperalgesia. The results represent the latency to hindpaw withdrawal in response to radiant heat in mice treated i.pl. with PGE2 or saline (S). Mice were tested (in the paw injected with PGE2 or its solvent) 10 min after the i.pl. injection. Morphine, LP1, 7a, 7c, 7d, 7e, or their solvent (S) was administered s.c. 20 min before the i.pl. injection. Statistically significant differences between the values obtained in mice i.pl. injected with saline and PGE2: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and between the values obtained in mice treated with PGE2 alone or associated with morphine or LP1: ##p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test).

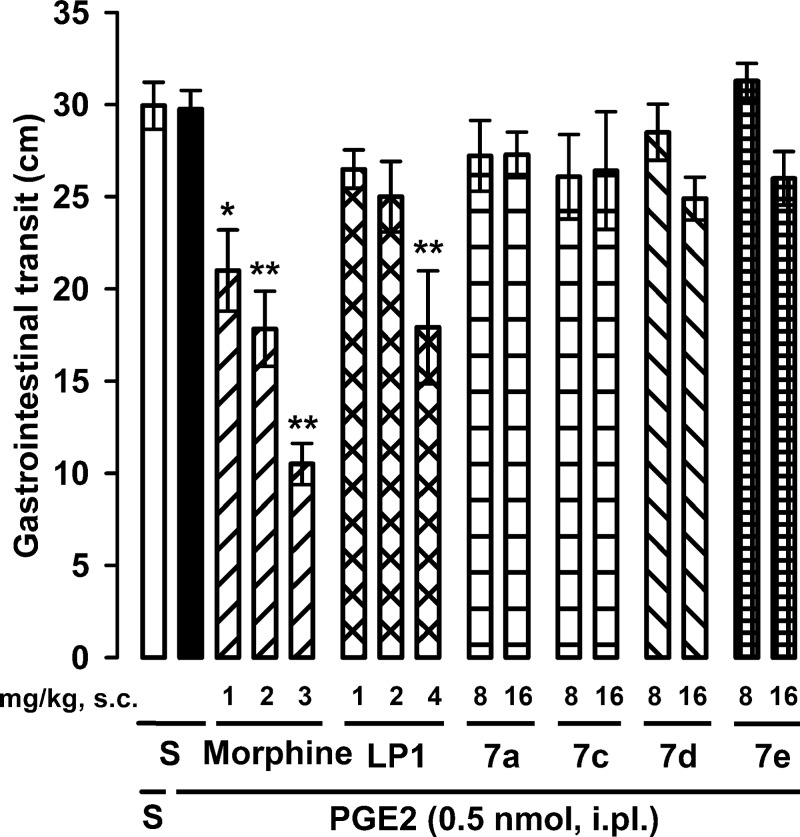

As constipation is a known opioid-induced side effect dependent on the activation of the ß-arrestin pathway,12,13 we also tested the effects of derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e on gastrointestinal transit. Immediately after the evaluation of the behavioral responses to heat stimulus, mice received intragastrically an activated charcoal solution. The charcoal meal traveled about 30 cm of the small intestine in either mouse treated i.pl. with saline or PGE2, indicating that the administration of PGE2 does not influence gastrointestinal transit (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Effects of morphine, LP1, and derivatives 7a, 7c, 7d, and 7e on gastrointestinal transit. Immediately after the evaluation of PGE2-induced hyperalgesia [i.e., 30 min after the s.c. administration of morphine, LP1, 7a, 7c, 7d, or 7e or saline (S)], mice were given a 0.5% charcoal suspension intragastrically. Transit of the charcoal was measured 30 min after its ingestion. Each bar and vertical line represents the mean ± SEM of values obtained in 6–7 mice. Statistically significant differences between the values obtained in saline-treated group and mice treated with morphine or LP1: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test).

Morphine already induced significant gastrointestinal transit inhibition at a dose devoid of antihyperalgesic effect (1 mg/kg), and this effect dose-dependently increased reaching values of distance traveled by the charcoal meal as low as 10.5 cm at the highest tested dose of the opioid (3 mg/kg) (compare Figures 5 and 6). Instead, LP1 inhibited gastrointestinal transit only at the highest dose tested (4 mg/kg), which induced a maximal antihyperalgesic effect (compare Figures 5 and 6). These results indicate that the MOR agonist/DOR antagonist LP1 has a more favorable safety profile than morphine.

However, the administration of 7a, 7c, 7d, or 7e (8–16 mg/kg, s.c.) did not alter gastrointestinal transit distances, as the charcoal meal traveled approximately 30 cm of the small intestine in all cases (Figure 6). Although these derivatives were able to act in vitro as opioid agonists mediating ERK1,2 phosphorylation, someone could assume that they may activate the ß-arrestin pathway and thus are unable to decrease gastrointestinal transit. Animals administered with these derivatives did not show either a Straub tail response (data not shown), which is a known centrally induced opioid effect.38

In summary, we have repurposed the N-modified benzomorphan scaffold to develop novel LP1 derivatives to further understanding the requirements for MOR interaction. A secondary amido N-substituent, as well as an ortho- and/or ortho/meta-methyl introduction to the phenyl ring, resulted in retention of MOR agonism. Derivatives 7a, 7e, 7c, and 7d were MOR agonists with a peculiar functional profile, being 7e a biased MOR agonist, able to stimulate G-protein pathway, and 7a, 7c, and 7d unbiased MOR agonists, able to stimulate ERK1,2 activity.

ERKs activation can be facilitated by distinct pathways mediated by G-proteins or β-arrestins dependent pathways. Fast activation of ERKs (2 min) is usually mediated by G-proteins resulted in the nuclear translocation of phosphorylated ERKs, whereas a slower activation of ERKs (10 min), the time sets that was used in our studies, is mediated by β-arrestins and resulted in the cytosolic retention of the phosphorylated ERKs. Different MOR agonists activate ERKs via β-arrestins dependent or independent pathways, thus resulting in differential subcellular localization of activated ERKs and altering their effect on gene transcription driven by the agonist.36 In addition to opioid receptor-mediated activation of ERKs via β-arrestins, β2AR stimulation resulted in ERKs activation via a β-arrestin dependent pathway.39

Compounds provided with functional selectivity could open new possibilities in opioid drug development. Indeed, biased MOR agonists toward G-protein are analgesics with low side effects incidence while biased MOR agonist toward β-arrestin could be useful to treat hypermotility disorders.

Besides the notable antinociceptive and antihyperalgesic effect, the dual-target profile of LP1 conferred a safer profile resulting in a less gastrointestinal transit inhibition than morphine. In accordance with in vitro data, synthesized derivatives did not elicit any significant antinociceptive and antihyperalgesic effect. Differences of pharmacokinetic could explain the low correlation between the in vivo inability to decrease gastrointestinal transit and the in vitro evidence. In conclusion, we found hits able to segregate physiological responses downstream of the receptor signaling that could be optimized.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by University of Catania grant (PdR 2016-2018) to Lorella Pasquinucci. The authors acknowledge Fabbrica Italiana Sintetici (Italy) for cis-(±)-N-normetazocine and Raffaele Morrone (CNR, ICB Catania) for MS. We acknowledge support by the OPENSCREEN-GR (MIS 5002691) funded by the Operational Programme NSRF 2014-2020 and cofinanced by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund). We also acknowledge Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO, grant SAF2016-80540-R). M. C. Ruiz-Cantero was supported by an FPU grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture, and Sports.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- MOR

mu opioid receptor

- DOR

delta opioid receptor

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- KOR

kappa opioid receptor

- MS

mass spectrometry

- Ki

inhibition constant

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- HEK293

human embryonic kidney 293

- ERK1

2, extracellular regulated kinase 1 and 2

- TFLs

tail flick latencies

- PGE2

Prostaglandin E2

- β-arrestins

β2AR, β-adrenergic receptor

- s.c.

subcutaneous

- i.p.

intraperitoneal

- i.pl.

intraplantar

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00549.

Experimental procedures for the synthesis and characterization of the compounds, radioligand binding, adenylyl cyclase inhibition, ERK1,2 activations, tail-flick, PGE2-induced hyperalgesia, and drug-induced gastrointestinal transit inhibition assays (PDF)

Author Contributions

L.P., R.T., and C.P. designed all paper experiments, analyzed and discussed results, and wrote the paper. L.P., R.T., and E.A. designed and synthesized new compounds. C.P. performed in vivo experiments. O.P. and E.Ar. performed and analyzed radioligand binding experiments. A.M., L.S., and M.D. participated to the statistical analysis and characterized compounds. Z.G. and P.P. performed and analyzed in vitro functional experiments. E.J.C. and M.C.R.-C. performed and analyzed in vivo experiments. All authors have participated in the writing refinement and given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Zhu L.; Cui Z.; Zhu Q.; Zha X.; Xu Y. Novel Opioid Receptor Agonists with Reduced Morphine-like Side Effects. Mini Rev. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 1603–1610. 10.2174/1389557518666180716124336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnaturi R.; Aricò G.; Ronsisvalle G.; Parenti C.; Pasquinucci L. Multitarget opioid ligands in pain relief: New players in an old game. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 108, 211–228. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnaturi R.; Aricò G.; Ronsisvalle G.; Pasquinucci L.; Parenti C. Multitarget Opioid/Non-opioid Ligands: A Potential Approach in Pain Management. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016, 23, 4506–4528. 10.2174/0929867323666161024151734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nastase A. F.; Griggs N. W.; Anand J. P.; Fernandez T. J.; Harland A. A.; Trask T. J.; Jutkiewicz E. M.; Traynor J. R.; Mosberg H. I. Synthesis and Pharmacological Evaluation of Novel C-8 Substituted Tetrahydroquinolines as Balanced-Affinity Mu/Delta Opioid Ligands for the Treatment of Pain. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1840–1848. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky A. T.; Sandweiss A.; Hu J.; Bilsky E. J.; Cain J. P.; Kumirov V. K.; Lee Y. S.; Hruby V. J.; Vardanyan R. S.; Vanderah T. W. Novel fentanyl-based dual μ/δ-opioid agonists for the treatment of acute and chronic pain. Life Sci. 2013, 93, 1010–1016. 10.1016/j.lfs.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei W.; Vekariya R. H.; Ananthan S.; Streicher J. M.. A Novel Mu-Delta Opioid Agonist Demonstrates Enhanced Efficacy With Reduced Tolerance and Dependence in Mouse Neuropathic Pain Models. J. Pain 2019, 19, pii: S1526−5900. 10.1016/j.jpain.2019.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harland A. A.; Yeomans L.; Griggs N. W.; Anand J. P.; Pogozheva I. D.; Jutkiewicz E. M.; Traynor J. R.; Mosberg H. I. Further Optimization and Evaluation of Bioavailable, Mixed-Efficacy μ-Opioid Receptor (MOR) Agonists/δ-Opioid Receptor (DOR) Antagonists: Balancing MOR and DOR Affinities. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 8952–69. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand J. P.; Kochan K. E.; Nastase A. F.; Montgomery D.; Griggs N. W.; Traynor J. R.; Mosberg H. I.; Jutkiewicz E. M. In vivo effects of μ-opioid receptor agonist/δ-opioid receptor antagonist peptidomimetics following acute and repeated administration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 2013–2027. 10.1111/bph.14148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietis N.; Niwa H.; Tose R.; McDonald J.; Ruggieri V.; Filaferro M.; Vitale G.; Micheli L.; Ghelardini C.; Salvadori S.; Calo G.; Guerrini R.; Rowbotham D. J.; Lambert D. G. In vitro and in vivo characterization of the bifunctional μ and δ opioid receptor ligand UFP-505. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 2881–2896. 10.1111/bph.14199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C. New concepts in opioid analgesia. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2018, 7, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnaturi R.; Chiechio S.; Salerno L.; Rescifina A.; Pittalà V.; Cantarella G.; Tomarchio E.; Parenti C.; Pasquinucci L. Progress in the development of more effective and safer analgesics for pain management. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 183, 111701. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manglik A.; Lin H.; Aryal D. K.; McCorvy J. D.; Dengler D.; Corder G.; Levit A.; Kling R. C.; Bernat V.; Hübner H.; Huang X. P.; Sassano M. F.; Giguère P. M.; Löber S.; Duan D.; Scherrer G.; Kobilka B. K.; Gmeiner P.; Roth B. L.; Shoichet B. K. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature 2016, 537, 185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond R. A.; Lucero Garcia-Rojas E. Y.; Hegde A.; Walker J. K. L. Therapeutic Potential of Targeting ß-Arrestin. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 124. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnaturi R.; Montenegro L.; Marrazzo A.; Parenti R.; Pasquinucci L.; Parenti C. Benzomorphan skeleton, a versatile scaffold for different targets: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 155, 492–502. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnaturi R.; Marrazzo A.; Parenti C.; Pasquinucci L. Benzomorphan scaffold for opioid analgesics and pharmacological tools development: A comprehensive review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 148, 410–422. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnaturi R.; Parenti C.; Prezzavento O.; Marrazzo A.; Pallaki P.; Georgoussi Z.; Amata E.; Pasquinucci L.. Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships of LP1 Derivatives: N-Methyl-N-phenylethylamino Analogues as Novel MOR Agonists. Molecules 2018, 23, pii: E677. 10.3390/molecules23030677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Prezzavento O.; Marrazzo A.; Amata E.; Ronsisvalle S.; Georgoussi Z.; Fourla D. D.; Scoto G. M.; Parenti C.; Aricò G.; Ronsisvalle G. Evaluation of N-substitution in 6,7-benzomorphan compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 4975–1482. 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenti C.; Turnaturi R.; Aricò G.; Marrazzo A.; Prezzavento O.; Ronsisvalle S.; Scoto G. M.; Ronsisvalle G.; Pasquinucci L. Antinociceptive profile of LP1, a non-peptide multitarget opioid ligand. Life Sci. 2012, 90, 957–961. 10.1016/j.lfs.2012.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Parenti C.; Turnaturi R.; Aricò G.; Marrazzo A.; Prezzavento O.; Ronsisvalle S.; Georgoussi Z.; Fourla D. D.; Scoto G. M.; Ronsisvalle G. The benzomorphan-based LP1 ligand is a suitable MOR/DOR agonist for chronic pain treatment. Life Sci. 2012, 90, 66–70. 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parenti C.; Turnaturi R.; Aricò G.; Gramowski-Voss A.; Schroeder O. H.; Marrazzo A.; Prezzavento O.; Ronsisvalle S.; Scoto G. M.; Ronsisvalle G.; Pasquinucci L. The multitarget opioid ligand LP1’s effects in persistent pain and in primary cell neuronal cultures. Neuropharmacology 2013, 71, 70–82. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Turnaturi R.; Aricò G.; Parenti C.; Pallaki P.; Georgoussi Z.; Ronsisvalle S. Evaluation of N-substituent structural variations in opioid receptor profile of LP1. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 2832–42. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Parenti C.; Amata E.; Georgoussi Z.; Pallaki P.; Camarda V.; Calò G.; Arena E.; Montenegro L.; Turnaturi R.. Synthesis and Structure-Activity Relationships of (−)-cis-N-Normetazocine-Based LP1 Derivatives. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, pii: E40. 10.3390/ph11020040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Turnaturi R.; Prezzavento O.; Arena E.; Aricò G.; Georgoussi Z.; Parenti R.; Cantarella G.; Parenti C. Development of novel LP1-based analogues with enhanced delta opioid receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 4745–4752. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Turnaturi R.; Montenegro L.; Caraci F.; Chiechio S.; Parenti C. Simultaneous targeting of MOR/DOR: A useful strategy for inflammatory pain modulation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 847, 97–102. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2019.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicario N.; Pasquinucci L.; Spitale F. M.; Chiechio S.; Turnaturi R.; Caraci F.; Tibullo D.; Avola R.; Gulino R.; Parenti R.; Parenti C. Simultaneous Activation of Mu and Delta Opioid Receptors Reduces Allodynia and Astrocytic Connexin 43 in an Animal Model of Neuropathic Pain. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 7338–7354. 10.1007/s12035-019-1607-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinucci L.; Turnaturi R.; Calò G.; Pappalardo F.; Ferrari F.; Russo G.; Arena E.; Montenegro L.; Chiechio S.; Prezzavento O.; Parenti C. (2S)-N-2-methoxy-2-phenylethyl-6,7-benzomorphan compound (2S-LP2): Discovery of a biased mu/delta opioid receptor agonist. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 168, 189–198. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brine G. A.; Berrang B.; Hayes J. P.; Carroll F. I. An improved resolution of (±)-cis-N-normetazocine. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1990, 27, 2139–2143. 10.1002/jhet.5570270753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Accolla M. L.; Turnaturi R.; Sarpietro M. G.; Ronsisvalle S.; Castelli F.; Pasquinucci L. Differential scanning calorimetry approach to investigate the transfer of the multitarget opioid analgesic LP1 to biomembrane model. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 77, 84–90. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romera J. L.; Cid J. M.; Trabanco A. A. Potassium iodide catalysed monoalkylation of anilines under microwave irradiation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 8797–8800. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prezzavento O.; Arena E.; Sánchez-Fernández C.; Turnaturi R.; Parenti C.; Marrazzo A.; Catalano R.; Amata E.; Pasquinucci L.; Cobos E. J. (+)-and (−)-Phenazocine enantiomers: Evaluation of their dual opioid agonist/σ(1) antagonist properties and antinociceptive effects. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 125, 603–610. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers S. R. Opioid receptor-coupled second messenger systems. Life Sci. 1991, 48, 1991–2003. 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fourla D. D.; Papakonstantinou M. P.; Vrana S.; Georgoussi Z. Selective interactions of spinophilin with the C-terminal domains of the δ- and μ-opioid receptors and G-proteins differentially modulate opioid receptor signaling. Cell. Signalling 2012, 24, 2315–2328. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morou E.; Georgoussi Z. Expression of the third intracellular loop of the delta-opioid receptor inhibits signaling by opioid receptors and other G protein coupled receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005, 315, 1368–1379. 10.1124/jpet.105.089946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou M. P.; Karoussiotis C.; Georgoussi Z. RGS2 and RGS4 proteins: New modulators of the κ-opioid receptor signaling. Cell. Signalling 2015, 27, 104–114. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoussi Z.; Georganta E.-M.; Milligan G. The other side of opioid receptor signaling: Regulation by protein-protein interaction. Curr. Drug Targets 2012, 13, 80–102. 10.2174/138945012798868470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H.; Loh H. H.; Law P. Y. Beta-arrestin-dependent mu-opioid receptor-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) Translocate to Nucleus in Contrast to G protein-dependent ERK activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 73, 178–190. 10.1124/mol.107.039842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grösch S.; Niederberger E.; Geisslinger G. Investigational drugs targeting the prostaglandin E2 signaling pathway for the treatment of inflammatory pain. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 2017, 26, 51–61. 10.1080/13543784.2017.1260544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath C.; Gupta M. B.; Patnaik G. K.; Dhawan K. N. Morphine-induced straub tail response: mediated by central mu2-opioid receptor. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 263, 203–205. 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90543-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy S. K.; Drake M. T.; Nelson C. D.; Houtz D. A.; Xiao K.; Madabushi S.; Reiter E.; Premont R. T.; Lichtarge O.; Lefkowitz R. J. beta-arrestin-dependent, G protein-independent ERK1/2 activation by the beta2 adrenergic receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 1261–1273. 10.1074/jbc.M506576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.