Abstract

Background

Clinical research in acupuncture has been criticized for not reflecting real-world practice in terms of diagnosis and intervention. This study aimed to collect data on the principles of diagnosis and selection of acupoints from Korean medicine doctors (KMDs) and analyze the patterns and priorities in decision-making.

Methods

The study design was based on the data of an actual patient with functional dyspepsia (FD) (according to Rome III criteria) to create simulated patients, and a KMD specialized in gastrointestinal disorders was allocated to collect the clinical information as objectively as possible. Sixty-nine KMDs were recruited to diagnose a simulated patient based on the actual patient's clinical information, in a manner similar to that performed in their clinics.

Results

After the diagnostic procedures were completed, the pattern identification, selected acupoints, reasons for choosing them, and importance of symptoms for deciding their diagnoses were documented. The information needed was clearly distinguishable from those routinely asked in western medicine, and information regarding fecal status, abdominal examination, appetite status, pulse diagnosis, and tongue diagnosis were listed as vital. The doctors identified the patient's pattern as “spleen-stomach weakness”, “liver qi depression”, or “food accumulation or phlegm-fluid retention”. The most frequently selected acupoints were CV12, LI4, LR3, ST36, and PC6.

Conclusion

There are common acupoints across different patterns, but pattern-specific acupoints were also recommended. These results can provide useful information to design clinical research and education for better clinical performance in acupuncture that reflects real-world practice.

Keywords: Acupuncture, Functional dyspepsia, Diagnostic procedure, Pattern identification, Acupoint

1. Introduction

Although randomized controlled trial (RCT) is a good research methodology, it often does not provide useful information that can be directly applied in clinical settings. Some researchers have argued that current clinical studies on acupuncture do not reflect the real-world practice, especially regarding diagnostic procedures and interventions.1 They tend to rely on a top-down approach because RCTs outnumber case reports or case series.2 A top-down approach includes the possibility that the research was detached from the actual clinical practice.2 In the early 2000s, there were several studies on how well acupuncture treatment reflects clinical practice.3, 4, 5, 6 These studies are highly valuable in determining the crucial aspects in terms of pattern diagnosis and selecting acupuncture points (acupoints). Nevertheless, they have certain limitations because they focus on finding a consensus among only a small number of doctors and researchers. Recently, pattern identification has been included in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11) of the World Health Organization.7 In line with this trend, acupuncture practitioners and researchers would be expected to activate and will pay more attention to the ‘pattern identification’ process in the diagnostic process for acupuncture treatment.7, 8, 9, 10

Acupuncture is a complex intervention. When a patient visits the doctor, a survey of the illness is conducted, followed by diagnosis and intervention plans. The doctor instructs the patient to lie down on a bed, inserts needles into specific points called acupoints on the patient's body, and then often induces responses called “deqi” through certain manipulation techniques. There are many complicated steps underlying this simple process. In the so-called traditional medicine's diagnostic process, the doctor obtains necessary information from the patient, makes a diagnosis described in terms of traditional medical patterns, and then decides which acupoints to stimulate and how to trigger deqi. Despite the necessity of a standardized process in both therapeutic settings and clinical trials,11 but academic approaches were being conducted rarely.12

Functional dyspepsia (FD) includes symptoms such as pain or burning in the gastroduodenal region, postprandial fullness, or early satiation without causes identifiable by conventional diagnostic means and has a high prevalence globally.13, 14 Current treatments for FD include antibiotics against Helicobacter pylori, proton pump inhibitors, low-dose tricyclic antidepressants, or psychological treatments.15 Nevertheless, patients who are skeptical about these methods may prefer complementary and alternative therapies, such as acupuncture treatment.16, 17, 18

In this paper, we attempted to bridge the gap between clinical trials and practical situations with respect to their convergence into a complex algorithm: what information is gathered from the patient, what pattern diagnosis is made, how acupoints are selected, and how all this information leads to the establishment of therapeutic principles. This study aimed to collect data on the principles of diagnosis and selection of acupoints from Korean medicine doctors (KMDs) and analyze patterns and priorities in decision-making based on the data of an actual patient with FD.

2. Methods

This study was conducted to evaluate the pattern diagnosis used when KMDs performed acupuncture therapy using the data of a single FD patient (patient A). In real practice, it is not feasible for a single patient to visit several clinics. Therefore, we collected the patient information prior to the study, and four female researchers were trained to act as simulated patients, fully understanding the information of patient A. The trained researchers were aware of all the collected information from the patient beforehand and conducted several trial simulations with a KMD before the study. This was done so that the study could proceed as realistically as possible, as if the KMDs were diagnosing an actual patient. Next, the researchers visited each clinic and answered questions of each of the KMDs. The KMDs conducted pattern diagnosis, and selected acupoints based on the given clinical information. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong (KHNMC-OH-IRB 2013-018).

2.1. Recruitment of a patient with functional dyspepsia and patient data collection

A patient diagnosed with FD based on Rome III criteria,19 aged between 20 and 60 years of age, was recruited. We excluded individuals with peptic ulcers or gastroesophageal reflux disease confirmed by esophagogastroduodenoscopy in the past year or those reporting a history of surgery related to the gastrointestinal tract, structural gastrointestinal diseases causing digestive symptoms, consumption of drugs that might affect the gastrointestinal tract, irritable bowel syndrome, or diagnosis of depression (Beck Depression Inventory ≥20). The patient signed a consent form agreeing to participate in this study.

To provide KMDs with the necessary information for the diagnosis, we discussed with the experts and conducted several simulations regarding the types and methods of patient information that can be collected. A researcher (KMD specialized in internal medicine) collected the following patient information: physical and demographic characteristics (age, sex, height, weight, blood pressure, pulse, occupation, and educations), chief complaint, present illness, past history, social history, and other states (e.g., appetite, digestion, bowel movement, urine, pitting edema, sweating, thirst, sleep, cold and heat, and fatigue). We videotaped the overall data collection process, including the patient walking into the clinic, verbally stating cardinal symptoms, pulse diagnosis, and abdominal examination process, and then attached the researcher's documentary explanation. The researcher also recorded the complexion, lip condition, eye and skin condition, and tongue condition (tongue manifestation, color, and fur), and then photographed the entire body, as well as the anterior and lateral side of the face. Additionally, a picture of the tongue was taken using a tongue diagnosis system. Furthermore, additional clinical information was gathered using the following devices and methods: Iris diagnosis [IRS-1000, Seoul, Korea],20 Ryodoraku (electro-dermal measurement of the 12 meridians, SME-5800N, Neomyth, Korea),21, 22 heart rate variability [HRV analyzer, SA-3000P, MEDICORE, Korea],22, 23 body composition analysis test [INBODY 720, BIOSPACE, Korea]).24 Finally, the patient completed the pattern diagnosis questionnaires for constitution (Questionnaire for the Sasang Constitution Classification, QSCC-II+),25 cold and heat,26 static blood,27 phlegm-retained fluid,28 Ping-Wei-San questionnaire,29 and fatigue due to overexertion,30 which were validated for identification of each pattern. All of the above patient information was prepared to provide information upon KMD's request if necessary for patient diagnosis.

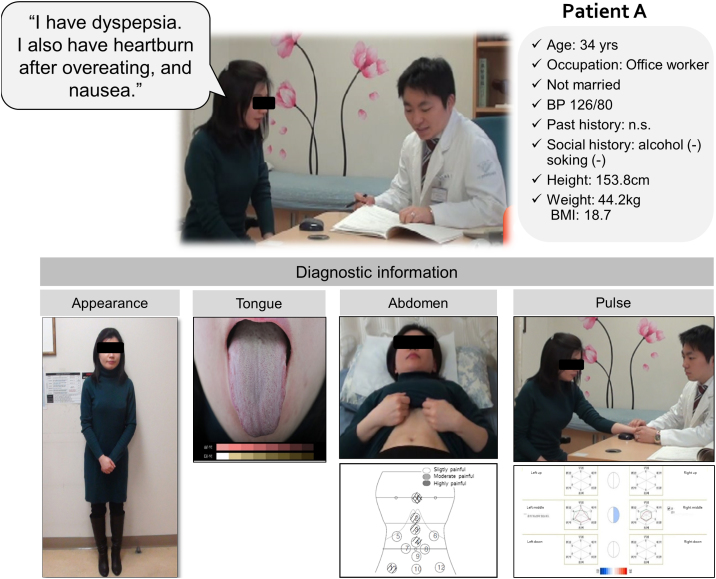

2.2. Brief case summary

The patient was a 34-year-old female with FD, who mainly complained of heartburn, nausea, belching, and bowel sounds. She usually ate a small amount of food, and the symptoms became worse after meals. Her meal times were usually irregular due to her employment at an office in a stressful environment. She also complained of headache, coldness of the hand and foot, and edema, especially in the morning. Representative characteristics observed were pale and reddened complexion, moist skin and lips, red tongue with white fur, and floating pulse on both pulse examinations. Tenderness of CV17, tenderness or rigidity of CV12 or 13, stiffness of rectus abdominis, and fullness in the chest and left hypochondrium were remarkable observations. Her previous medical history was not remarkable (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Representative clinical information provided to the physicians.

2.3. Simulated diagnostic procedures regarding the pattern diagnosis and selection of acupoints

To recruit KMDs, we randomly selected KMDs from Seoul and Gyeonggi-do Province listed in the “2012 KMDs’ membership list” published by the Association of Korean Medicine and telephoned to ask if they were willing participate. KMDs with more than three years of clinical experience and who had treated an FD patient in the past year were included. We excluded KMDs who did not routinely use acupuncture in practice.

After participants were determined as eligible, each trained simulated patient visited the clinics and underwent the simulated diagnostic procedures concerning the pattern diagnosis and selection of acupoints. The simulated patient first told the KMDs, “After watching the patient's video, please diagnose me comfortably through your routine medical practice as if I am an actual patient. If you need any more information regarding the patient, please let me know.” The simulated patient answered the KMDs’ questions as similarly as possible to the actual patient's description. Once the KMDs obtained all the information needed for diagnosis, they answered questions about the pattern diagnosis for the patient, grounds of the pattern diagnosis, and acupoints that they would use for the treatment.

2.4. Data analysis

To analyze the principles of diagnosis and priorities in decision-making of the KMDs, the following process was carried out. First, hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to identify the rules regarding how medical information was used to decide the patterns. The similarity between the grounds of patterns was evaluated by applying Jaccard distance31 using diagnostic criteria, and a neighbor-joining tree was generated using the ratio of the size of the symmetric difference based on the diagnosis. Second, we applied the bottom-up hierarchical clustering to determine the similarity based on diagnostic evidence. The phylogenetic tree32 was generated by hierarchical clustering using KMDs. From the cluster of a KMD, the other KMDs were located to determine if they were included in the same cluster. Due to the diversity of medical terminologies used, three experienced experts qualitatively grouped the patterns as per their original meanings.

The acupoints were analyzed as follows: first, the pictogram was generated by grouping the selected acupoints based on their distribution (upper extremity, lower extremity, chest, abdomen, and back and shoulder); next, the frequency analysis of each acupoint was performed according to the corresponding pattern identification.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the participating Korean medicine doctors

After screening 694 KMDs via telephone, 118 qualified participants agreed to participate. Participation was withdrawn by 49 KMDs during coordination of visitation schedules, while data from 69 KMDs remained for the final analysis. The average age of the participants was 45.6 years, and the average clinical career duration was 17 years. In their routine clinical practice, the participants mainly used traditional Korean Medicine style acupuncture with diagnosis primarily based on patterns (84.1%), while a relatively high percentage (46.4%) stated that they used Sa-am acupuncture, a Korean traditional method of acupuncture based on the theory of five elements. In addition, participants responded that other various types of acupuncture style, including Dong-Si acupuncture, myofascial trigger-point acupuncture, or constitutional acupuncture, as well as pharmacopuncture, or laser acupuncture, were used as their routine treatment methods (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Traditional Korean Medicine Doctors

| Categories | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 30–39 | 14 (20.3) |

| 40–49 | 40 (58.0) | |

| 50–59 | 11 (16.0) | |

| More than 60 | 4 (5.8) | |

| Gender | Male | 60 (87.0) |

| Female | 9 (13.0) | |

| Educational status | Bachelor's degree | 19 (27.5) |

| Master's degree | 4 (5.8) | |

| Doctor's degree | 46 (66.7) | |

| Clinical experience (year) | 5–10 | 5 (7.2) |

| 10–15 | 24 (34.8) | |

| 15–20 | 15 (21.7) | |

| More than 20 | 25 (36.2) | |

| Korean Medicine specialist | Yes | 16 (23.2) |

| No (general practitioner) | 53 (76.8) | |

| Style of acupuncture that participants usually use in clinical practice | TKM style acupuncture with diagnosis primarily based on patterns | 58 (84.1) |

| Sa-am acupuncture, a Korean traditional method of acupuncture based on the theory of five elements | 32 (46.4) | |

| Others | 33 (47.8) |

TKM, tratidional Korean Medicine.

3.2. Analyses of pattern identifications

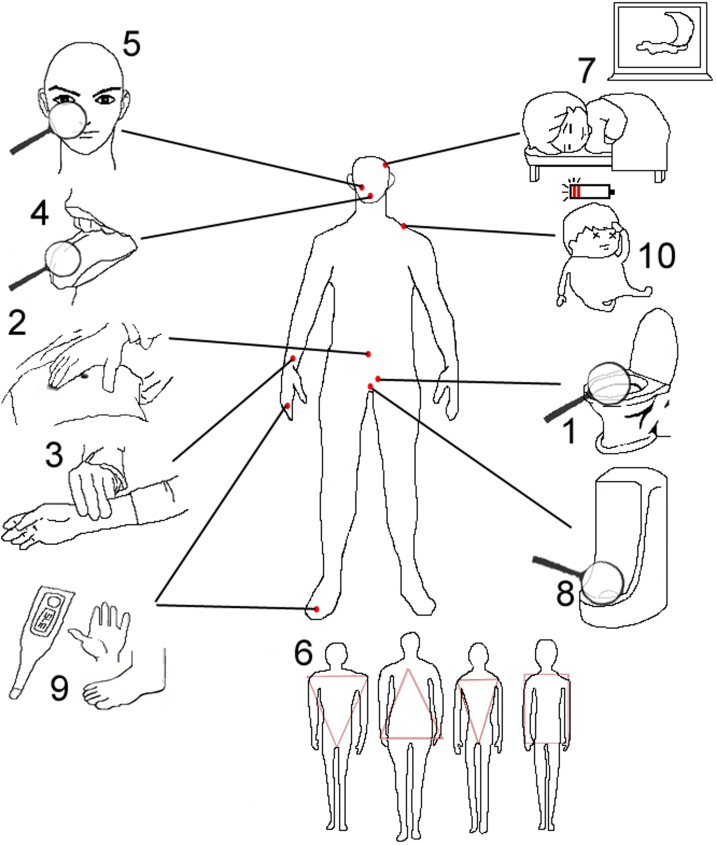

3.2.1. Analysis of the importance of patient information

In addition to chief complains (Fig. 1), the KMDs regarded bowel movement condition including fecal state as the most important patient information in the process of the pattern diagnosis and selection of acupoints (n = 44). It was followed by abdominal examination (n = 38), pulse diagnosis (n = 32), tongue diagnosis (n = 27), inspection (n = 23), balance of body shape (n = 19), sleeping state (n = 12), condition of urine (n = 12), warm heat of the hands and feet (n = 10), and fatigue (n = 9) in that order (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Prioritized information for the diagnosis and selection of acupoints in functional dyspepsia, where the numbers (1–10) indicate the priority rank of information according to the Korean medicine doctors’ responses.

They also reported that they needed more information in addition to the information we provided including detailed eating habits (types of food consumed, whether meals were consumed at regular intervals, whether water was consumed before or after meals, preferred drinking water temperature, activities performed after meals, indigestible foods consumed, habit of overeating or eating at night, and causes of aggravated symptoms), information about pressure points [e.g., details of transport points (specific points on the back where the qi of the visceral organs is infused) with tenderness on pressure)], more information regarding bowel movement condition and abdominal examination, diagnosis opinion on gastroscopy, breathing rate, images of oral check-up, body type, color of the eye ground, and strength of voice.

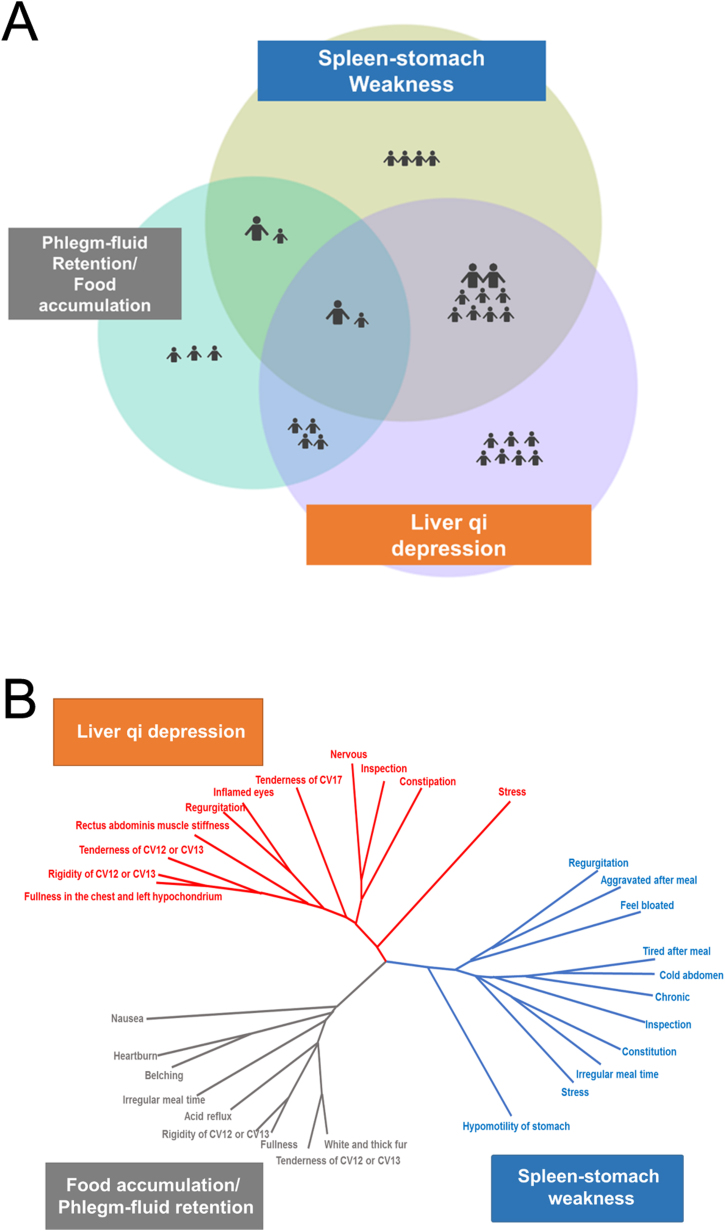

3.2.2. Analysis of the pattern diagnosis types

We classified the responses of the pattern diagnoses into three categories: spleen–stomach weakness (SSW; n = 53, 79%), liver qi depression (LQD; n = 49, 73%), and food accumulation or phlegm-fluid retention (FAPR; n = 29, 43%). Among the three categories, 14 KMDs (21%) understood the patient through one pattern diagnosis, whereas 53 KMDs (79%) understood the patient through more than two or more diagnoses (Fig. 3A). Fig. 3B shows the results of hierarchical clustering, showing which patient information was used when the KMDs determined the pattern diagnosis. Furthermore, the results show that the KMDs conducted pattern diagnosis and diagnosed the patient with SSW based on cardinal symptoms, such as eating habits, results of abdominal diagnosis, and body type. They diagnosed the patient with LQD based on pressure pain and constipation observed through abdominal examination. When they diagnosed the patient with FAPR, cardinal symptoms, such as heartburn or nausea and the result of tongue diagnosis formed the basis of the diagnosis. The results of hierarchical clustering analysis based on the diagnostic grounds used by each KMD were classified into three groups for diagnostic reasons (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

The pattern diagnosis of patient A. (A) Sixty-seven responses were categorized into liver qi depression, spleen–stomach weakness, and food accumulation or phlegm-fluid retention by content analysis (two had no information). The large icon indicates 10 responses of Korean medicine doctors, and the small icon indicates one response; (B) Phylogenetic tree of the clinical information and pattern diagnosis. To identify the priority of information for the pattern diagnosis, a neighbor-joining tree based on Jaccard distances by hierarchical clustering is created, and each node indicates clinical information of patient A. Stress, hypomotility of the stomach, and nausea were regarded as most important in liver qi depression, spleen-stomach weakness, and food accumulation or phlegm-fluid retention.

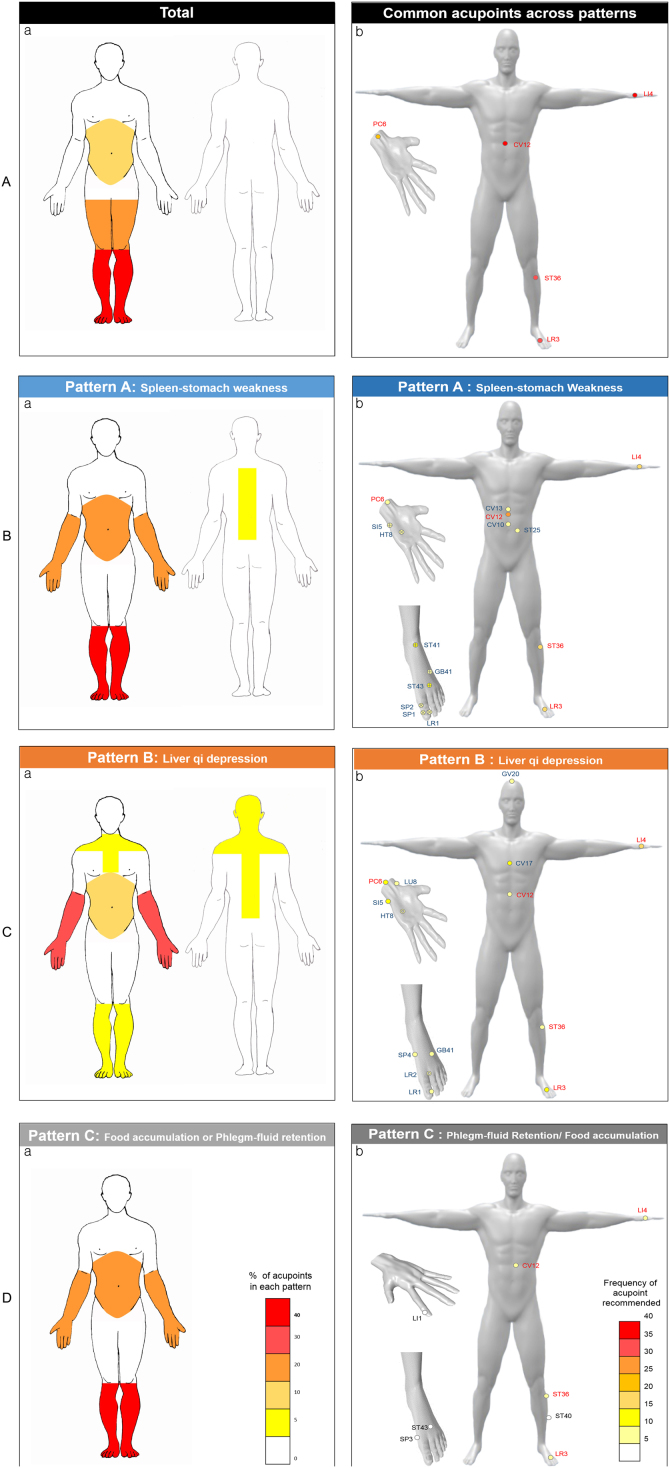

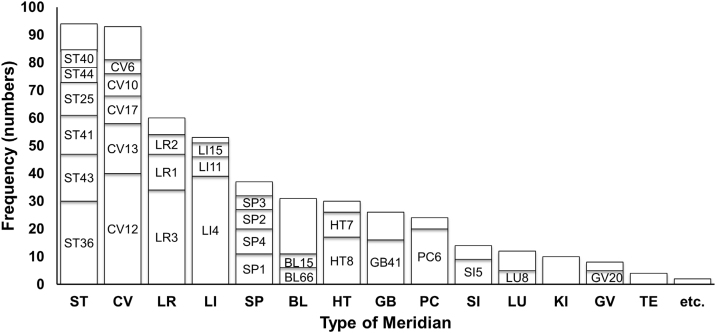

3.2.3. Analysis of selected acupoints

Overall, acupoints of the lower limbs, upper limbs, and abdomen were commonly used. The acupoints of the abdomen were more commonly used than other pattern diagnoses in the case of SSW. On the other hand, acupoints of the chest, back, and shoulder were used more, and acupoints of the abdomen were less commonly used as compared to the other pattern diagnoses in the case of LQD (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Distribution of acupoints by pattern diagnosis, where the proportion of the location of selected acupoints was encoded by the pattern diagnosis. (A) Common acupoints regardless of the pattern diagnosis and selected acupoints regarding the pattern diagnosis; (B) spleen–stomach weakness-specific acupoints; (C) liver qi depression-specific acupoints; (D) food accumulation or phlegm-fluid retention-specific acupoints (circle: acupoints; X + circle: acupoints used for Sa-am acupuncture treatment).

This study found that a total of 91 different acupoints were recommended across all KMDs. Among these points, CV12, LI4, LR3, and ST36 were frequently used by KMDs (60%, 58%, 51%, and 45%, respectively), which were commonly included in all patterns. Overall, the distinct features of the results were that selection of adjacent points was performed using abdominal acupoints, and selection of distant points was performed using a combination of five transport points and acupoints used in Sa-am acupuncture. When we examined those points from the meridian and collateral views, we determined that the stomach meridian and conception vessel, liver meridian, large intestine meridian, and spleen meridian were the most frequently mentioned (Supplementary Fig. S2).

3.2.4. Analysis of acupoints by pattern diagnosis

Forty-six acupoints were mentioned for treatment of SSW, with CV12 (n = 25), LI4 (n = 18), ST36 (n = 16), LR3 (n = 15), ST43 (n = 12), and ST41 (n = 11) used in descending order of frequency. Nourishing stomach meridian (n = 8) and nourishing spleen meridian (n = 5) were mentioned in Sa-am acupuncture (n = 13) (Fig. 4B). Sixty-five acupoints (n = 197) were mentioned for treatment of LQD, with LI4 (n = 15) and LR3 (n = 14) used the most, and CV17, PC6 (each n = 10), HT7, HT8 (each n = 8), LR1, LR2, ST36 (each n = 7), CV12 (n = 6), GV20, SP4, GB41, and LU8 (each n = 5) mentioned in descending order of frequency. Sedating liver meridian was used in Sa-am acupuncture (n = 3) (Fig. 4C). Forty-three acupoints (n = 87) were used in diagnosing FAPR, with CV12 (n = 9), ST36 (n = 7), LI4 (n = 6), LR3 (n = 5), and ST40 (n = 4) most used among them (Fig. 4D).

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to research how doctors decided which principles of acupuncture therapy they would use in treating a patient with FD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the diagnostic process of performing a pattern diagnosis, using patient information, and of selecting acupoints for the treatment.

Overall analysis of the clinical data by inspection, listening, inquiry, and palpation to help identify and chose the diagnostic pattern is a key feature of traditional East Asian practice.33 This could provide an integrative perspective on the etiology, pathology, and treatment methods.34, 35, 36 In this study, KMDs categorized the FD patient (patient A) into three pattern diagnoses of SSW, LQD, and FAPR. As shown in Fig. 3A, 80% of the KMDs understood that the symptoms were complicated, because they diagnosed the patient as having two or more pattern diagnoses. In traditional Korean medicine (TKM), it is thought that the causes of disease do not act lopsidedly; rather, disease is thought to be a result of the combination of several causes or of the interactions between the causes and body condition. This study is a good example eliciting this characteristic of the traditional East Asian medicine. In the case of patient A, the identified pattern diagnoses were not independent, but mutually related and could be converted. There are many direct and indirect causes of the disease, and each pattern diagnosis is interconnected as the disease course progresses from the acute phase to the chronic phase. The pattern diagnosis result for patient A could be differentiated, irrespective of the criteria for the diagnosis being problematic organs, provoking causes, or pathological results. Unlike the classification of diseases, each relationship of pattern diagnosis is parallel and mutually converted rather than exclusive, and these characteristics must be considered when designing clinical trials and developing an education program for clinical performance skills. Regarding the above issues, Kim23 suggested that Western medicine emphasizes a “perceived object,” and involves diagnosis and treatment by fixing and objectifying the diseases, whereas TKM emphasizes the “experience of perception,” and involves diagnosis and treatment by reflecting upon the phenomenon occurring between the principal and associated symptoms.

By analyzing the characteristics for the selection of acupoints, we found that there were pattern-specific acupoints utilized in addition to the common acupoints used for certain major symptoms. Therefore, the selection of acupoints was determined by combining common acupoints for alleviating the chief symptom, along with specific acupoints to eliminate hypothesized causal factors of the diagnosed pattern. The upper and lower limbs, where special acupoints such as five transport points, source points, and lower sea points of the six bowels are located, were the regions where most acupoints were selected even though they were distant from the actual areas of digestive symptom presentation. The acupoints ST36, CV12, LI4, and LR3, which were frequently selected in our analysis, were consistent with those selected in clinical trials of FD published over the years.37, 38, 39, 40 Additionally, in our analysis, the five transport points GB41, HT8, HT7, SI5, LR1, and LR2, used for Sa-am acupuncture therapy were more frequently selected in the pattern-specific scenario. Sa-am acupuncture provides basic acupuncture prescriptions to restore balance by applying the engendering and restraining cycle relationships using the five transport points on the 12 meridians.41, 42 This might reflect the real clinical features of Korean acupuncture.

This study was the first to focus on the process rather than on the clinical outcomes. We observed the natural flow of the diagnostic process by each KMD; thus, it had the advantage of predicting actual clinical features. Actual practical scenarios and experiences should be reflected in the process of standardization. The diversity of pattern diagnoses or selection of acupoints may result from the holistic view by considering individual differences. Thus, it is important to note that diversity needs to be considered in the standardization process. Furthermore, this study offers many ideas to educate students and evaluate students’ clinical practice ability by connecting clinical skills with textbook education. For example, clinical performance examination (CPX) evaluates subjective decision and practice under clinical situations. This study recorded the actual decision-making processes of KMDs that could be utilized to develop CPX for student education. Additional research, including the process of clinical reasoning and selection of treatment methods, is needed to design actual CPX scenarios.

Although this study utilized the symptoms of real patients to understand the diagnostic process and acupoint selection process in actual Korean Medicine practice better, it possesses a few limitations. First, the design of this study could vary from the actual diagnostic process. The KMDs participated during clinic hours, and the level of activity differed. Some KMDs asked for information such as eating habits, status of diet, or tenderness on the transport points, which were not investigated, and faced difficulty in making the proper diagnosis. Moreover, we used simulated patients rather than the actual patient, so the information was restricted even though we had trained the participants to offer information as realistically as possible. In future research, a more systematic and practical approach is needed to collect actual clinical data. Second, only one FD patient participated in the study, and identical medical information was distributed to approximately 70 KMDs (based on that patient) who provided responses about the diagnosis process; therefore, the results could not be generalized. Moreover, the symptoms of the actual patient were not severe. Finally, this study was not intended to evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment, but to acquire insight into the complex process of diagnosis and acupoint selection. Further clinical studies are needed to identify which pattern diagnosis and acupoints are appropriate for improved efficacy of acupuncture treatment.

In conclusion, we observed the clinical diagnostic process of KMDs using simulated FD patients based on data from an actual patient. These results can provide useful information to design clinical research and education to improve clinical performance in acupuncture that reflects the real-world practice. Further clinical studies are necessary to reflect the actual practical protocol on other diseases in addition to FD.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (grant K18182). The authors would like to thank all participating doctors of Korean Medicine, the four simulated patients (Hye Jin Seo, Eun Byeol Jo, Mi Ni Hwang, and Min Yeong Park), and Dr. Dong Kun Kim for their personal contributions. We are grateful to So Ra Ahn, Seon-Yong Lee, and Jong-Wu Lee for their help in preparing illustrations and translation.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conceptualization: HJP, SYK, SHH, and ISL. Methodology: SYK, SHH, YSB, YC, and HJP. Validation: HJP. Formal analysis: SHH, HJP, YSK, JK, and HL. Investigation: SKK, SJK, and JWP. Data curation: SKK, SJK, and JWP. Writing – original draft: SYK, SHH, and HJP. Writing – review & editing: SYK, and HJP. Visualization: SYK, SHH, and HJP. Supervision: HJP. Project administration: HJP. Funding acquisition: HJP.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine (grant K18182).

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Kyung Hee University Hospital at Gangdong (KHNMC-OH-IRB 2013-018).

Data availability

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Supplementary figures associated with this article can be found in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2020.100419.

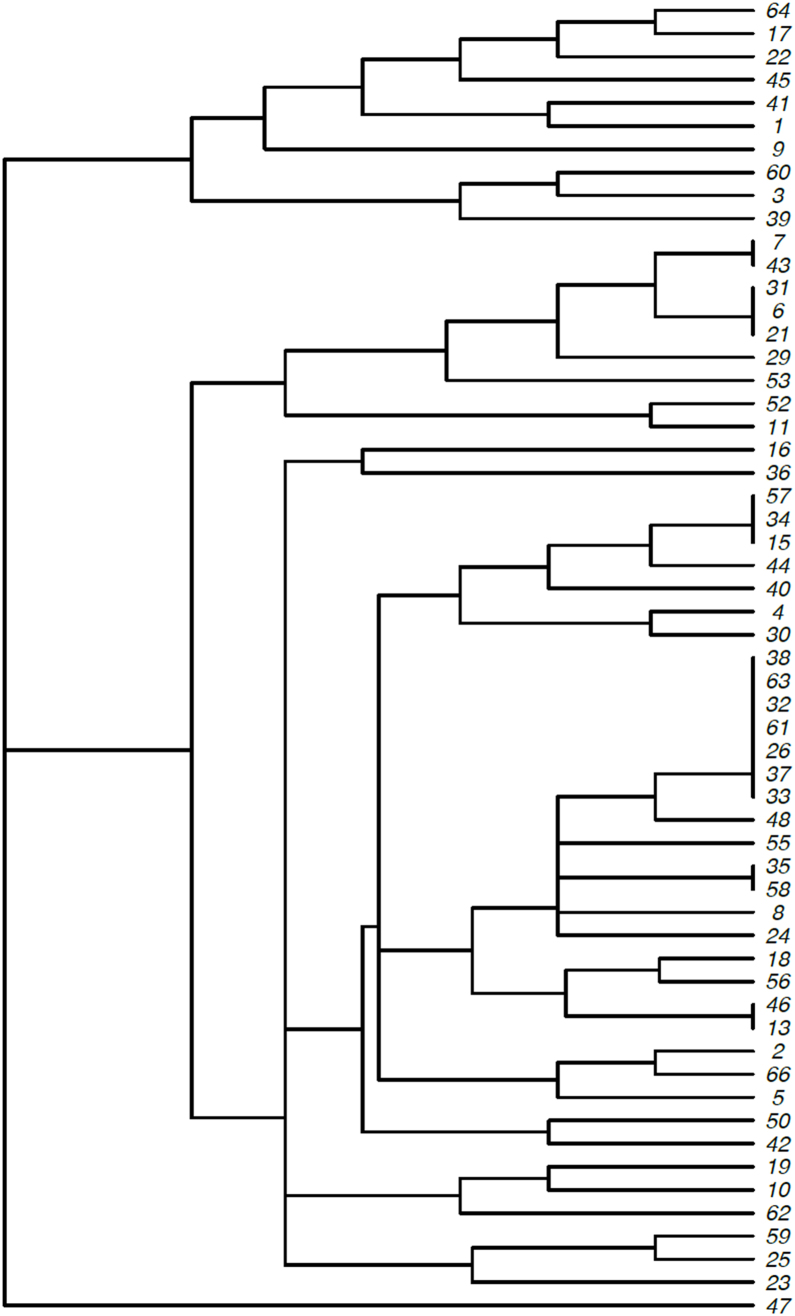

Supplementary Fig. S1 Phylogenetic tree of Korean medicine doctors (KMDs) based on the diagnostic similarity. Hierarchy clustering was created among KMDs (n = 66) who were diagnosed with a similar pattern diagnosis on a similar basis.

Supplementary Fig. S2 Used acupoints based on the meridian (BL, bladder meridian; GB, gallbladder meridian; HT; heart meridian; KI, kidney meridian; LI, large intestine meridian; LR, liver meridian; LU, lung meridian; PC, pericardium meridian; SI, small intestine meridian; SP, spleen meridian; ST, stomach meridian; TE, triple energizer meridian).

Supplementary materials

The following are the supplementary figures related to this article:

Supplementary Fig. S1.

Phylogenetic tree of Korean medicine doctors (KMDs) based on the diagnostic similarity. Hierarchy clustering was created among KMDs (n = 66) who were diagnosed with a similar pattern diagnosis on a similar basis.

Supplementary Fig. S2.

Used acupoints based on the meridian (BL, bladder meridian; GB, gallbladder meridian; HT; heart meridian; KI, kidney meridian; LI, large intestine meridian; LR, liver meridian; LU, lung meridian; PC, pericardium meridian; SI, small intestine meridian; SP, spleen meridian; ST, stomach meridian; TE, triple energizer meridian).

References

- 1.Choi S.M. Korea Institute of Oriental Medicine; 2013. Status survey for the internationalization of the clinical research of acupuncture and moxibustion and the establishment of foundations for collaborations. Available from: http://www.ndsl.kr/ndsl/search/detail/report/reportSearchResultDetail.do?cn=TRKO201300031245. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langevin H.M., Wayne P.M., MacPherson H., Schnyer R., Milley R.M., Napadow V. Paradoxes in acupuncture research: strategies for moving forward. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2011/180805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogeboom C.J., Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C. Variation in diagnosis and treatment of chronic low back pain by traditional Chinese medicine acupuncturists. Complement Ther Med. 2001;9:154–166. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalauokalani D., Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C. Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: diagnosis and treatment patterns among acupuncturists evaluating the same patient. Southern Med J. 2001;94:486–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman K., Hogeboom C., Cherkin D. How traditional Chinese medicine acupuncturists would diagnose and treat chronic low back pain: results of a survey of licensed acupuncturists in Washington State. Complement Therap Med. 2001;9:146–153. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2001.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sherman K.J., Cherkin D.C., Hogeboom C.J. The diagnosis and treatment of patients with chronic low-back pain by traditional Chinese medical acupuncturists. J Alternat Complement Med. 2001;7:641–650. doi: 10.1089/10755530152755199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes J., Fisher P., Espinosa S., Brinkhaus B., Fonnebo V., Rossi E. Traditionally trained acupuncturists’ views on the World Health Organization traditional medicine ICD-11 codes: a Europe wide mixed methods study. Eur J Integr Med. 2019;25:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson N., Bovey M., Lee J., Zaslawski C., Tian P., Kim T. How do acupuncture practitioners use pattern identification – an international web-based survey? Eur J Integr Med. 2019;32:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S., Jeong J., Lim J., Kim B. Acupuncture using pattern-identification for the treatment of insomnia disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Integr Med Res. 2019;8:216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.imr.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvim D.T., Ferreira A.S. Inter-expert agreement and similarity analysis of traditional diagnoses and acupuncture prescriptions in textbook- and pragmatic-based practices. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;30:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M., Gray J.M., Haynes R.B., Richardson W.S. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berle C., Cobbin D., Smith N., Zaslawski C. An innovative method to accommodate Chinese medicine pattern diagnosis within the framework of evidence-based medical research. Chin J Integr Med. 2011;17:824–833. doi: 10.1007/s11655-011-0893-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahadeva S., Goh K.L. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661–2666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Talley N.J. Liver. Functional dyspepsia: advances in diagnosis and therapy. Gut Liver. 2017;11:349–357. doi: 10.5009/gnl16055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacy B., Talley N., Locke G., III, Bouras E., DiBaise J., El-Serag H. Current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiarioni G., Pesce M., Fantin A., Sarnelli G. Complementary and alternative treatment in functional dyspepsia. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:5–12. doi: 10.1177/2050640617724061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ouyang H., Chen J. Therapeutic roles of acupuncture in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:831–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou W., Su J., Zhang H. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for the treatment of functional dyspepsia: meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22:380–389. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tack J., Talley N.J., Camilleri M., Holtmann G., Hu P., Malagelada J.R. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y., Park S., Park Y., Park Y. A review of iridology. J Korea Inst Orient Med Diagn. 2013;17:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noh S., Kim K., Yoon Y., Yang G., Kim J., Lee B. Ryodoraku application for diagnosis: a review of Korean literature. Korean J Acupunct. 2011;28:125–135. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park J., Yoon S. A clinical study on the relationship between functional dyspepsia (FD) and biosignals from heart rate variability (HRV) and Yangdorak diagnosis. J Korean Orient Med. 2007;28:80–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim H., Kim B., Kim W. Comparative study of acute dyspepsia, functional dyspepsia, organic dyspepsia by HRV(heart rate variability) J Orient Neuropsychiatry. 2010;21:75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey B., LeCheminant G., Hope T., Bell M., Tucker L. A comparison of the agreement, internal consistency, and 2-day test stability of the InBody 720, GE iDXA, and BOD POD® gold standard for assessing body composition. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci. 2018;22:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang H., Lee E., Koh B., Song I. A study on the validity to make a diagnosis of Taeumin by QSCCII (Questionnaire for the Sasang Constitution Classification II) J Sasang Const Med. 2001;13:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae N., Yang D., Park Y.J.P., Lee Y., Oh S.H. Development of questionnaires for Yol patternization. J Korea Inst Orient Med Diagn. 2006;10:98–108. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang D., Park Y., Park Y., Lee S. Development of questionnaires for Blood Stasis pattern. J Korea Inst Orient Med Diagn. 2006;10:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park J., Yang D., Kim M., Lee S., Park Y. Development of questionnaire for Damum patternization. J Korea Inst Orient Med Diagn. 2006;10:64–77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lim J., Park Y., Park Y., Lee S., Oh H. A Study on reliability and validity of the Pyungweesan Patternization Questionnaire by the pathogenesis analysis. J Korea Inst Orient Med Diagn. 2007;11:59–67. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoon T., Park Y., Lee S., Park Y., Oh H. Development of questionnaires for pathogenesis analysis of Bojungikgitang symptom(II) J Korea Inst Orient Med Diagn. 2007;11:45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan P.N., Steinbach M., Kumar V. Pearson Education; India: 2018. Introduction to data mining. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hodge T., Jamie M., Cope T. A myosin family tree. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3353–3354. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birch S., Alraek T., Bovey M., Lee M., Lee J., Zaslawski C. Overview on Pattern identification – history, nature and strategies for treating patients: a narrative review. Eur J Integr Med. 2020;35:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J.A., Ko M.M., Lee J., Kang B.K., Alraek T., Birch S. Extraction of clinical indicators that are associated with the heat/nonheat and excess/deficiency patterns in pattern identifications for stroke. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2015/869894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific . WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila: 2007. WHO international standard terminologies on traditional medicine in the western pacific region. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiseman N., Ye F. 2nd ed. Paradigm Publications; Massachusetts: 1998. A practical dictionary of Chinese medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo L., Zhang C., Guo X. Long-term efficacy and safety research on functional dyspepsia treated with electroacupuncture and Zhizhu Kuanzhong capsule. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2011;31:1071–1077. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Han G., Ko S.J., Park J.W., Kim J., Yeo I., Lee H. Acupuncture for functional dyspepsia: study protocol for a two-center, randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lima F.A., Ferreira L.E., Pace F.H. Acupuncture effectiveness as a complementary therapy in functional dyspepsia patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:202–207. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032013000200036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park Y.C., Kang W., Choi S.-M., Son C.-G. Evaluation of manual acupuncture at classical and nondefined points for treatment of functional dyspepsia: a randomized-controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:879–884. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park M., Kim S. A modern clinical approach of the traditional Korean Saam acupuncture. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2015. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/703439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin C., Park H.-J., Chae Y., Ha E., Park H.-K., Lee H.-S. Korean acupuncture: the individualized and practical acupuncture. Neurol Res. 2007;29(Suppl 1):10–15. doi: 10.1179/016164107X172301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available upon reasonable request.