Abstract

An agonist–antagonist switching strategy was performed to discover novel PPARα antagonists. Phenyldiazenyl derivatives of fibrates were developed, bearing sulfonimide or amide functional groups. A second series of compounds was synthesized, replacing the phenyldiazenyl moiety with amide or urea portions. Final compounds were screened by transactivation assay, showing good PPARα antagonism and selectivity at submicromolar concentrations. When tested in cancer cell models expressing PPARα, selected derivatives induced marked effects on cell viability. Notably, 3c, 3d, and 10e displayed remarkable antiproliferative effects in two paraganglioma cell lines, with CC50 lower than commercial PPARα antagonist GW6471 and a negligible toxicity on normal fibroblast cells. Docking studies were also performed to elucidate the binding mode of these compounds and to help interpretation of SAR data.

Keywords: PPARs, sulfonimide, amide, antagonist, phenyldiazenyl, cytotoxicity

Since the discovery of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs), a large body of knowledge about these nuclear receptors has been collected to date.1 PPARs control important metabolic functions in the body, mainly implicated in lipid and glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and energetic metabolism, through the activation of three subtypes, namely PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ.2 PPARα and PPARγ agonists are currently marketed to treat metabolic disorders, such as hyperlipidemias, hypertriglyceridemias, and type 2 diabetes. PPARα agonists, such as fibrates, represent therapeutic options useful to decrease lipoprotein and triglyceride levels,3,4 whereas PPARγ agonists thiazolidinediones (TZDs) improve insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes and in metabolic disorders as obesity, dyslipidemia, and metabolic syndrome.5 However, a moderate activation of PPARs has been emerging as a novel therapeutic opportunity to contrast metabolic disorders; partial agonists, inverse agonists, and antagonists have been synthesized to investigate the pharmacological actions obtained by a reduced activation of PPARs. Several PPAR antagonists have been described,6 together with molecular mechanisms implicated in the PPAR repression. While some antagonists were identified by a random screening, many of these compounds have been obtained by chemical manipulation of known agonists, according to the helix12-folding inhibition hypothesis proposed by Hashimoto.7

A reduced PPARα activity has been shown to be beneficial in different types of cancer, where a metabolic switch from glucose to fatty acid oxidation (FAO) metabolism occurs. Some tumors, including leukemia, prostate, ovarian, and renal cell carcinomas, are strongly dependent on FAO for survival and proliferation.8 PPARα antagonists showed antitumor effects in different cancer cell lines,9 as chronic lymphocytic leukemia,10 renal cell carcinoma,11 glioblastoma,12 colorectal and pancreatic cancer,13 and paraganglioma.14,15

In the search for novel PPAR antagonists, in this work we describe an agonist–antagonist switching design. The modification of the carboxylic head of PPARα agonists has been proven to be a successful strategy to obtain antagonists: we reported in previous works the discovery of sulfonimide derivatives of fibrates, showing antagonistic properties on PPARα.16,17 In previous studies, we synthesized novel PPAR agonists, based on a clofibrate or gemfibrozil skeleton.18,19 Some of these derivatives showed good PPAR activation, with submicromolar potency. We selected the stilbene derivative (Lead compound I) and the phenyldiazenyl derivative (Lead compound II) as starting compounds to obtain the corresponding methyl and phenyl sulfonimide derivatives 1a–b and 2a–b (Figure 1), in the attempt to switch the pharmacological behavior from agonists to antagonists. Lead compound I is a selective PPARα agonist (EC50 1.0 μM), whereas Lead compound II is a dual PPARα/γ agonist, with a higher PPARα efficacy and submicromolar potency (EC50 PPARα 0.6 μM, PPARγ 1.4 μM).

Figure 1.

From Lead compounds I and II to sulfonimide derivatives 1a–b and 2a–b. Reagents and conditions: methane- (a) or benzenesulfonamide (b), EDC, DMAP, dry dichloromethane, 0 °C–rt, 24 h, yield 44–65%.

Lead compounds I and II were obtained as previously described.18,19 Carboxylic acids were transformed in sulfonimide derivatives 1a–b and 2a–b by treatment with methane- or benzenesulfonamide, 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide (EDC), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (Figure 1).

These compounds were evaluated for agonist activity on the human PPARα (hPPARα) (Table 1) and PPARγ (hPPARγ) subtypes (data not shown). For this purpose, GAL-4 PPAR chimeric receptors were expressed in transiently transfected HepG2 cells according to a previously reported procedure.20,21 Due to cytotoxicity exhibited by these compounds on HepG2 cells above 5 μM, their activity was evaluated at only three concentrations (1, 2.5, and 5 μM) and compared with that of the corresponding reference agonists (Wy-14,643 for PPARα and Rosiglitazone for PPARγ) (Supporting Information, Figure S1) whose maximum induction was defined as 100%. Only 1a–b and 2a showed a weak selective activity toward PPARα in the concentration range taken into consideration (Emax 17–29%), whereas no activity was observed on PPARγ (data not shown). Given that 2b had no detectable PPARα/γ activity, it was tested as an antagonist by conducting a competitive binding assay in which PPARα and PPARγ activity at a fixed concentration of the reference agonists Wy-14,643 and Rosiglitazone, respectively, was measured in cells treated with increasing concentrations of 2b. Compound 2b completely inhibited PPARα activity with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration of 1.2 ± 0.1 μM showing also a simultaneous inhibition of PPARγ even though with lower potency and activity (IC50 14 ± 2 μM; Imax 87%).

Table 1. hPPARα Activity by GAL-4 PPAR Transactivation Assay for Synthesized Compoundsa.

| hPPARα |

hPPARα |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Emax% | Imax% | IC50 μM | ID | Emax% | Imax% | IC50 μM |

| 1a | 17 ± 6 | – | – | 4c | 32 ± 7 | – | – |

| 1b | 24 ± 6 | – | – | 4d | i | 96 ± 4 | 2.72 ± 0.85 |

| 2a | 29 ± 6 | – | – | 10a | 24 ± 2 | 78 ± 2 | 7.0 ± 1.7 |

| 2b | i | 99 ± 1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 10b | 28 ± 3 | 12 ± 1 | – |

| 3a | i | 100 ± 1 | 0.17 ± 0.12 | 10c | 28 ± 2 | 62 ± 7 | 12.3 ± 0.9 |

| 3b | i | 99 ± 1 | 0.33 ± 0.14 | 10d | 12 ± 1 | 71 ± 2 | 12.1 ± 1.1 |

| 3c | i | 100 ± 1 | 0.21 ± 0.13 | 10e | i | 100 ± 1 | 0.24 ± 0.04 |

| 3d | i | 92 ± 1 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 13a | i | 93 ± 6 | 3.32 ± 1.31 |

| 3e | i | 100 ± 1 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 13b | i | 87 ± 4 | 1.70 ± 0.25 |

| 3f | i | 88 ± 3 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 13c | 21 ± 1 | 67 ± 3 | 6.1 ± 0.8 |

| 3g | i | 69 ± 10 | 3.20 ± 0.44 | 13d | i | 94 ± 4 | 10.3 ± 2.7 |

| 4a | i | 94 ± 4 | 2.98 ± 1.02 | 13e | i | 100 ± 5 | 1.52 ± 0.22 |

| 4b | 12.0 ± 0.3 | 95 ± 6 | 2.67 ± 1.15 | ||||

i = activity below 5% at the highest tested concentration. Emax% represents the percentage of maximum fold induction obtained with PPARα agonist Wy-14,643, taken as 100%. Imax% represents the percentage of inhibition of the maximum effect obtained with the reference agonist Wy-14,643.

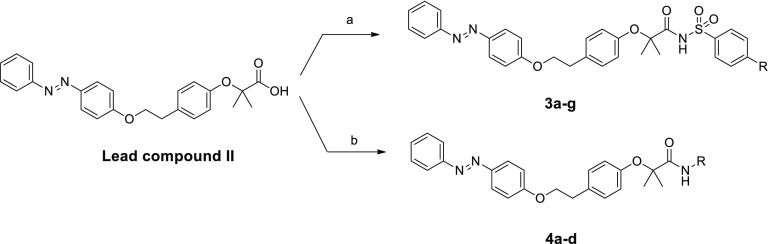

Based on these results, phenyldiazenyl compound 2b was selected as a novel scaffold to develop novel compounds by designing the benzenesulfonimide and amide derivatives displayed in Figure 2. In sulfonimide derivatives 3a–g, with the aim of probing further binding interactions inside the ligand binding domain (LBD), we introduced groups with different stereoelectronic properties in the para position, including hindered substituents containing an additional aromatic ring. As amide derivatives, we selected first the primary amide 4a and the butyl, phenyl, and benzyl secondary amides 4b–d. Next, a second series of compounds (Figure 2) was developed by replacing the azo moiety with amide or urea. Designed compounds were primary and secondary amides (10a–d and 13a–d) and benzenesulfonimide derivatives (10e and 13e).

Figure 2.

Chemical structures of final compounds 3a–g, 4a–d, 10a–e, and 13a–e.

The synthesis of benzenesulfonimides 3a–g and of amides 4a–d was performed starting from Lead compound II. Sulfonimides 3a–g were obtained by direct coupling of starting carboxylic acid with proper para-substituted phenylsulfonamides, with EDC and DMAP, in dry CH2Cl2 (Scheme 1). For compounds 3e–g, the p-substituted phenylsulfonamides were synthesized as previously reported.22 Amides 4b–d were synthesized by coupling Lead compound II with proper amines, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBt), and N-methylmorpholine (NMM) in DMF. For derivative 4a, the starting acid was reacted with ammonium chloride, under the conditions described.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Compounds 3a–g and 4a–d.

Reagents and conditions: (a) p-substituted benzenesulfonamide, EDC, DMAP, dry CH2Cl2, N2, 0 °C–rt, 24 h, yield 21–80%; (b) R–NH2, DCC, HOBt, NMM, DMF, rt, 24 h, yield 67–90%.

Final products 10a–e and 13a–e were obtained as depicted in Scheme 2. Phenol 5 was synthesized by reacting p-aminophenol with benzoyl chloride, in the presence of triethylamine (TEA) in dry DMF, whereas the reaction of p-aminophenol with phenylisocyanate, in dry acetonitrile, afforded phenol 6. Both phenols 5 and 6 were reacted with intermediate ester 7, synthesized by reaction of 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)phenol with ethyl 2-bromoisobutyrate.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Compounds 10a–e and 13a–e.

Reagents and conditions: (a) benzoyl chloride, TEA, dry DMF, N2, 0 °C–rt, 24 h, yield 70%; (b) phenylisocyanate, dry ACN, N2, reflux, 5h, yield 65%; (c) 7, PPh3, DIAD (diisopropyl azodicarboxylate), dry THF, 24 h, yield 54–97%; (d) 2 N NaOH, THF, reflux, 16 h, yield 57–63%; (e) R–NH2, DCC, HOBt, NMM, DMF, rt, 24 h, yield 29–98% (for amides 10a–d and 13a–d); benzenesulfonamide, EDC, DMAP, dry CH2Cl2, N2, 0 °C–rt, 24 h, yield 34–64% (for sulfonimides 10e and 13e); (f) ethyl 2-bromoisobutyrate, K2CO3, DMF, reflux, 4 h, yield 75%.

The Mitsunobu coupling of phenols 5 and 6 with ester 7 produced 8 and 11, which were hydrolyzed in basic conditions to acids 9 and 12. Final amides and sulfonimides 10a–e and 13a–e were obtained as previously described for compounds 3a–g and 4a–d.

All these compounds were evaluated for agonist activity on hPPARα (Table 1) and hPPARγ (data not shown) at different concentrations in the range 1–25 μM. Most compounds were either poorly active or inactive on both PPAR subtypes; thus, they were tested as antagonists, as reported above. Overall, tested compounds were completely inactive on PPARγ (data not shown).

Sulfonimides 3a–g showed a selective good antagonist profile on PPARα, with displacement activity toward reference compound Wy-14,643 ranging from 69% to 100%. The IC50 calculated for these compounds displayed a low micromolar potency, with being 3a, 3b, and 3c the most potent compounds (IC50 0.17, 0.33, and 0.21 μM, respectively). The increased steric hindrance in the para position by introduction of an additional aromatic ring (3f and 3g) decreased the antagonist activity (IC50 2.8 and 3.2 μM, respectively).

As regards amides 4a–d, they were also able to selectively antagonize PPARα exhibiting good efficacy (94–96%) and micromolar potency (2.67–2.98 μM). Only compound 4c was not tested as PPARα antagonist due to its residual activity (Emax 32%) on this receptor subtype. The two series of compounds developed by replacing the azo moiety with amide and urea exhibited similar behavior even though with small but significant differences. All these compounds showed selective and moderate ability to antagonize PPARα, with ureido derivatives 13a–d being more effective and potent compared to corresponding amides 10a–d.

Among compounds 10a–e and 13a–e, the two benzenesulfonimide derivatives 10e and 13e turned out to be the best PPARα antagonists, being able to completely abolish the activation promoted by the reference agonist Wy-14,643. In this case, 10e showed higher potency than 13e (0.24 vs 1.52 μM).

Considering that 3a–e, 10e, and 13e appeared as the most promising compounds in transactivation assay, showing a PPARα antagonist activity ranging from 92% to 100%, together with a potency in terms of IC50 values ranging from 0.17 to 1.52 μM, we selected these compounds to perform gene expression analysis. We analyzed whether 3a–e, 10e, and 13e could modulate the expression of the PPARα target gene carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A (CPT1A), a key enzyme involved in fatty acid β-oxidation, considered an in vitro model to study PPARα activation.22,23 Real-time quantitative PCR (RTqPCR) was employed to assess the effects of the compounds on CPT1A expression. Compounds were tested alone, or in the presence of the potent PPARα agonist GW7647, used as control. As expected, GW7647 robustly stimulated CPT1A expression (Figure 3), whereas compounds 3a–e, 10e, and 13e induced only a weak CPT1A mRNA expression. Notably, the combinations of GW7647 with 3a–e, 10e, or 13e were able to significantly repress CPT1A expression, supporting the antagonistic behavior of the novel compounds on PPARα (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Expression of PPARα target gene CPT1A. Data shown are the means ± SD of three determinations (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

We also explored the potential antiproliferative activity of 3a–e, 10e, and 13e in eight human cancer cell lines representative of four distinct tumor types. We selected three pancreatic (AsPC-1, BxPC-3, Capan-2), two colorectal (HT-29, SW480), two paraganglioma (PTJ64i, PTJ86i), and one renal (A498) cancer cell line, which express PPARα as reported in a previous study,14 or in the Expression Atlas database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/home). Preliminary MTT experiments were conducted by treatment of the eight cancer cell lines with 3a–e, 10e, and 13e, with the PPARα antagonist GW6471, or with the PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 for 72 h, at a single concentration (75 μM) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Effect of compounds on the viability of pancreatic (A), colorectal (B), paraganglioma (C), and renal (D) tumor cell lines. Cell viability was assessed by MTT assay using compounds at 75 μM for 72 h. Data shown are the means ± SD of duplicate experiments with quintuplicates determinations. *Statistically significant differences between control and each compound concentration (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001).

Overall, Wy-14,643 did not affect cell viability across the tumor cell lines tested (Figure 4), whereas novel compounds, as well as GW6471, showed antiproliferative activities, although with variable potency. Notably, all the novel PPARα antagonists had a more marked effect on cell viability in paraganglioma (PGL), as compared to the other cancer cell lines, with inhibition rates in PGL cells ranging from 59% to 98%, in line with the effects obtained with GW6471 in the same cancer cell lines (inhibition rates from 85% to 92%). 3c, 3d, and 10e emerged as the compounds showing more consistent and relevant antiproliferative activities across the eight cancer cell lines, with inhibition rates from 41% to 92% in the pancreatic cancer cell lines, from 52% to 98% in the colon cancer cell lines, from 84% to 98% in the PGL cell lines, and from 51% to 71% in the renal cancer cell line (Figure 4). Thus, we selected these compounds for further characterization of antiproliferative effects through concentration-dependent experiments.

Pancreatic, colorectal, paraganglioma, and renal cancer cell lines were incubated with 3c, 3d, and 10e for 72 h at concentrations from 0 μM to 24 μM (Figure 5). The treatments significantly reduced cell viability in a concentration-dependent manner, showing variable effects across the tested cancer cell lines. In particular, 3c, 3d, and 10e drastically and significantly decreased paraganglioma cell line viability, as shown by concentration–response curves (Figure 5, panels A, B, C) and cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values in the low micromolar range (Figure 5, panel D). Intriguingly, the novel compounds showed greater antiproliferative effects and lower CC50 values than those previously obtained with the reference compound GW6471 in the same paraganglioma cell lines.14 Remarkably, 3c, 3d, and 10e did not show toxicity against normal HFF-1 fibroblast cells, displaying CC50 values higher than 24 μM, which was the highest concentration used in our MTT assays, and good selectivity index (SI) values (Figure 5, panels A, B, C, D).

Figure 5.

Compounds 3c, 3d, and 10e affect viability in paraganglioma cancer cell lines with negligible effects on normal fibroblast cells. Concentration–response curves of 3c (A), 3d (B), and 10e (C) on viability of paraganglioma cancer cell lines (PTJ86i and PTJ64i) and of normal fibroblast cells (HFF-1). Cytotoxic effects were tested by MTT assay using compounds at the indicated concentrations for 72 h. Data shown are the means ± standard deviation of duplicate experiments with five replicates. Cytotoxic concentration (CC50) values are the drug concentrations required to inhibit 50% of cell viability. Selectivity index (SI) values were calculated for each compound as follows: CC50 on normal fibroblast cells (HFF-1)/CC50 on cancer cells (D). *Statistically significant differences between control and each compound concentration (*p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001).

Similarly, compounds 3c, 3d, and 10e showed CC50 values higher than 24 μM in pancreatic, colorectal, and renal cancer cell, except 3d that showed a CC50 of 16.99 μM in BxPC-3 and 10e that showed CC50 values of approximately 7 μM in pancreatic and colorectal cancer cell lines and of 4.6 μM in renal cancer cells (Supporting Information, Table S1).

To elucidate the binding mode of this series of compounds and to help interpretation of structure–activity relationship (SAR) data, we undertook docking studies using the GOLD Suite docking package (CCDC Software Limited: Cambridge, U.K.) with the X-ray crystal structure of PPARα in complex with the antagonist GW6471 (PDB ID: 1KKQ).24 In this structure GW6471, bearing an amide headgroup, does not interact with Y464 and pushes the H12 to assume an inactive and less structured conformation. The PPAR LBD is “Y-shaped” and is composed of a polar arm I, which is extended toward H12, a hydrophobic arm II, which is located between H3 and the β-sheet, and a hydrophobic entrance (arm III).

The most potent compounds 3a and 10e were chosen for docking as representative members of benzenesulfonimide derivatives bearing distal phenyldiazenyl and phenylbenzamide moieties, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 6, both compounds adopted a similar U-shaped configuration, wrapping around H3. The oxygen atom of the sulfonimide moiety of 3a (Figures 6A and S2, Supporting Information) was engaged in an H-bond with the OH group of Y314 side chain. Moreover, the phenyl ring of the benzenesulfonimide moiety was optimally oriented for a favorable π–π stacking interaction with the Y314 side chain, and the methyl group in para formed fruitful hydrophobic interactions with A441. The gem-dimethyl substituents were projected into the lipophilic “benzophenone pocket”,25 making further hydrophobic interactions. The central phenoxy ring also made a π–π stacking interaction with the F318 side chain, with the phenoxy oxygen forming a further H-bond with Nε2 of H440. The phenyldiazenyl group was surrounded by sulfur-containing residues such as C275, C276, M355, and M330, forming profitable sulfur–arene interactions.26 The ligand’s tail fitted well into arm II and positively contributed to overall binding through hydrophobic contacts with residues I272 of H3, L254 and L247 of H2′, and I241, I339, V332 of the β-sheet.

Figure 6.

Binding mode of compounds 3a (A, yellow sticks) and 10e (B, violet sticks) in PPARα LBD represented as green ribbon model. Only amino acids located within 4 Å of the bound ligand are displayed (white sticks) and labeled. H-bonds discussed in the text are depicted as dashed black lines.

By looking at the binding mode of compound 10e (Figures 6B and S3, Supporting Information), it was observed that an H-bond was also formed, through its carbonyl oxygen, with the OH group of the Y314 side chain, whereas the aromatic ring of the benzenesulfonamide moiety made hydrophobic interactions with V444 and F273. In addition, the central phenoxy ring was engaged in an edge-to-face π–π stacking interaction with the H440 side chain. The phenylbenzamide moiety, besides the hydrophobic contacts observed for 3a, formed two additional H-bonds with the T279 OH group and the NH backbone of A333 on the β-sheet.

The overlay of the docked pose of 3a and 10e with the X-ray crystal pose of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (Supporting Information, Figure S4A) revealed a similar binding mode, with analogous positioning of head groups and a similar orientation of the hydrophobic tail groups. Noteworthy, the benzenesulfonamide headgroup of 3a and 10e projected into an area that is usually occupied by the side chain of Y464 in PPARα LBD bound to agonist ligands, such as GW409544 (Supporting Information, Figure S4B).27 Thus, the benzenesulfonamide derivatives do not interact with this residue that is critical for receptor activation due to steric hindrance, likely forcing H12 out of the agonist bound position and inducing a PPARα LBD conformation that interacts efficiently with corepressors.

Docking studies allowed deriving some clues about SAR. As regards derivatives 3a–g, when the methyl group at position para of 3a was replaced with methoxy (3b) or chlorine (3c), the IC50 remained in the low micromolar range, suggesting that these compounds are able to form the same favorable interactions observed for 3a. Thus, the para position of the benzenesulfonimide moiety requires substituents with a certain degree of lipophilicity, but quite limited in size. In fact, the insertion of the more hydrophilic nitro group (3d), or the bulkier methylamide group (3e), caused a slight decrease in potency; for derivatives 3f and 3g, a further drop in PPARα antagonistic activity was observed, produced by the impaired accommodation of an additional aromatic ring into arm I of PPARα. The overlay of the docked poses of 3a and 3g (Figure S5A, Supporting Information) revealed that the benzyl amide substituent was shifted upward in arm I and dramatically altered the interactions pattern of the benzenesulfonimide group. Derivatives 4a–d, bearing the amide headgroup and phenyldiazenyl tail group, turned out to be less active because of the loss of profitable H-bonds and π–π stacking interactions with Y314 observed in docking experiments. On comparing the docked pose of 3a and 4c (Figure S5B, Supporting Information), it is clear that, despite a similar positioning of the phenyldiazenyl tail, the amide moiety was not properly oriented to engage an H bond with Y314. Also for derivatives 10a–e, the presence of the benzenesulfonamide group was critical for the antagonistic activity, as only derivative 10e displayed an IC50 in the low micromolar range. From the docked pose of 10e, it can be argued that the primary amide (10a) was no longer able to form the hydrophobic interactions with residues V444 and F273, whereas both aliphatic (10b) and aromatic groups (10c and 10d) could not be placed at an optimal distance to favorably interact with such residues. As shown in Figure S5C, the phenylbenzamide tails of both 10e and 10b displayed the same orientation; however, the butyl amide headgroup of 10b could not properly interact with Y314, but instead was oriented toward Q277. Thus, the weak interactions formed by the headgroup were unable to induce an antagonistic conformation. This might account for the slight receptor activation and, in turn, the low antagonistic activity shown by derivatives 10a–d. For derivatives 13a–e, the presence of the urea moiety at the tail group improved the antagonistic activity (see 13a and 13b) due to its propensity to extend more deeply into arm II and to make an H-bond with the C275 backbone. However, introduction of phenyl and benzyl substituents (13c and 13d) on the amide headgroup introduced steric restrictions, making it more difficult for the ligands to interact with Y314 and with the hydrophobic residues A441, V444, and F273. Again, the introduction of the benzenesulfonamide group increased potency (13e). As shown in Figure S5D, this moiety well anchored the ligand into arm I in a similar fashion to 10e. The presence of the sulfonyl group avoids the steric restrictions by rotation of the phenyl ring to a position that is better suited to interact with hydrophobic residues. Thus, the benzenesulfonamide moiety is a key structural feature in this series of derivatives to confer antagonistic activity.

In conclusion, this study led to the identification of novel sulfonimide and amide PPARα antagonists. Most potent compounds induced marked antiproliferative activity when tested in in vitro cancer cells expressing PPARα (pancreatic, colorectal, paraganglioma, and renal cancer cell lines). In addition, binding modes of representative benzenesulfonimide derivatives 3a and 10e helped to rationalize results from transactivation assay and give information about SAR of this class of compounds.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PPARs

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors

- TZDs

thiazolidinediones

- FAO

fatty acid oxidation

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- LBD

ligand binding domain

- DCC

N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- HOBt

1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate

- NMM

N-methylmorpholine

- TEA

triethylamine

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- CPT1A

carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A

- RTqPCR

real-time quantitative PCR

- PGL

paraganglioma

- CC50

median cytotoxic concentration.

Biography

Alessandra Ammazzalorso received her Ph.D. from the G. d’Annunzio University, Chieti-Pescara, Italy, in 2001. She is currently an Assistant Professor at Pharmacy Department, University of Chieti-Pescara. Her research interests include the design and synthesis of small-molecule drugs, mainly PPAR ligands and enzymatic inhibitors of nitric oxide synthases and aromatase. The results of these studies have been published in over 60 papers.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00666.

Experimental procedures, full characterization of compounds, 2D ligand-interaction diagrams of compounds into the PPAR binding pocket, NMR spectra (PDF)

This work was supported by FAR funds (Italian Ministry for Instruction, University and Research) assigned to A.A. The study was also supported by the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR), Progetti di Ricerca di Interesse Nazionale (PRIN) funds (Grant Number 2017EKMFTN_005), assigned to A.C.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Issemann I.; Green S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature 1990, 347, 645–650. 10.1038/347645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger J. P.; Akiyama T. E.; Meinke P. T. PPARs: therapeutic targets for metabolic disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2005, 26, 244–251. 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staels B.; Dallongeville J.; Auwerx J.; Schoonjans K.; Leitersdorf E.; Fruchart J.-C. Mechanism of action of fibrates on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation 1998, 98, 2088–2093. 10.1161/01.CIR.98.19.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsiki N.; Nikolic D.; Montalto G.; Banach M.; Mikhailidis D. P.; Rizzo M. The role of fibrate treatment in dyslipidemia: an overview. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 3124–3131. 10.2174/1381612811319170020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarafidis P. A. Thiazolidinedione derivatives in diabetes and cardiovascular disease: an update. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 22, 247–264. 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammazzalorso A.; De Filippis B.; Giampietro L.; Amoroso R. Blocking the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR): an overview. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 1609–1616. 10.1002/cmdc.201300250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y.; Miyachi H. Nuclear receptor antagonists designed based on the helix-folding inhibition hypothesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2005, 13, 5080–5093. 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudio I.; Fiegl M.; Andreeff M. Mitochondrial uncoupling and the Warburg effect: molecular basis for the reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2163–2166. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Lellis L.; Cimini A.; Veschi S.; Benedetti E.; Amoroso R.; Cama A.; Ammazzalorso A. The anticancer potential of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor antagonists. ChemMedChem 2018, 13, 209–219. 10.1002/cmdc.201700703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messmer D.; Lorrain K.; Stebbins K.; Bravo Y.; Stock N.; Cabrera G.; Correa L.; Chen A.; Jacintho J.; Chiorazzi N.; Yan X. J.; Spaner D.; Prasit P.; Lorrain D. A selective novel Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR)-α antagonist induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation of CLL cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 410–419. 10.2119/molmed.2015.00139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abu Aboud O.; Donohoe D.; Bultman S.; Fitch M.; Riiff T.; Hellerstein M.; Weiss R. H. PPARα inhibition modulates multiple reprogrammed metabolic pathways in kidney cancer and attenuates tumor growth. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2015, 308, C890–C898. 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti E.; d’Angelo M.; Ammazzalorso A.; Gravina G.; Laezza C.; Antonosante A.; Panella G.; Cinque B.; Cristiano L.; Dhez A. C.; Astarita C.; Galzio R.; Cifone M. G.; Ippoliti R.; Amoroso R.; Di Cesare E.; Giordano A.; Cimini A. PPARα antagonist AA452 triggers metabolic reprogramming and increases sensitivity to radiation therapy in human glioblastoma primary cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2017, 232, 1458–1466. 10.1002/jcp.25648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammazzalorso A.; De Lellis L.; Florio R.; Bruno I.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Giampietro L.; Maccallini C.; Perconti S.; Verginelli F.; Cama A.; Amoroso R. Cytotoxic effect of a family of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor antagonists in colorectal and pancreatic cancer cell lines. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2017, 90, 1029–1035. 10.1111/cbdd.13026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florio R.; De Lellis L.; di Giacomo V.; Di Marcantonio M. C.; Cristiano L.; Basile M.; Verginelli F.; Verzilli D.; Ammazzalorso A.; Prasad S. C.; Cataldi A.; Sanna M.; Cimini A.; Mariani-Costantini R.; Mincione G.; Cama A. Effects of PPARα inhibition in head and neck paraganglioma cells. PLoS One 2017, 12 (6), e0178995 10.1371/journal.pone.0178995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammazzalorso A.; De Lellis L.; Florio R.; Laghezza A.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Giampietro L.; Maccallini C.; Tortorella P.; Veschi S.; Loiodice F.; Cama A.; Amoroso R. Synthesis of novel benzothiazole amides: evaluation of PPAR activity and anti-proliferative effects in paraganglioma, pancreatic and colorectal cancer cell lines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 29, 2302–2306. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammazzalorso A.; Giancristofaro A.; D’Angelo A.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Giampietro L.; Maccallini C.; Amoroso R. Benzothiazole-based N-(phenylsulfonyl)amides as a novel family of PPARα antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21, 4869–4872. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammazzalorso A.; D’Angelo A.; Giancristofaro A.; De Filippis B.; Di Matteo M.; Fantacuzzi M.; Giampietro L.; Linciano P.; Maccallini C.; Amoroso R. Fibrate-derived N-(methylsulfonyl)amides with antagonistic properties on PPARα. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 58, 317–322. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippis B.; Giancristofaro A.; Ammazzalorso A.; D’Angelo A.; Fantacuzzi M.; Giampietro L.; Maccallini C.; Petruzzelli M.; Amoroso R. Discovery of gemfibrozil analogues that activate PPARα and enhance the expression of gene CPT1A involved in fatty acids catabolism. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 46, 5218–5224. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampietro L.; D’Angelo A.; Giancristofaro A.; Ammazzalorso A.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Linciano P.; Maccallini C.; Amoroso R. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of fibrate-based analogues inside PPARs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 7662–7666. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.09.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinelli A.; Godio C.; Laghezza A.; Mitro N.; Fracchiolla G.; Tortorella V.; Lavecchia A.; Novellino E.; Fruchart J. C.; Staels B.; Crestani M.; Loiodice F. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling investigation of new chiral fibrates with PPARα and PPARγ agonist activity. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 5509–5519. 10.1021/jm0502844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcelli L.; Gilardi F.; Laghezza A.; Piemontese L.; Mitro N.; Azzariti A.; Altieri F.; Cervoni L.; Fracchiolla G.; Giudici M.; Guerrini U.; Lavecchia A.; Montanari R.; Di Giovanni C.; Paradiso A.; Pochetti G.; Simone G. M.; Tortorella P.; Crestani M.; Loiodice F. Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of ureidofibrate-like derivatives endowed with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor activity. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 37–54. 10.1021/jm201306q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammazzalorso A.; Carrieri A.; Verginelli F.; Bruno I.; Carbonara G.; D’Angelo A.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Florio R.; Fracchiolla G.; Giampietro L.; Giancristofaro A.; Maccallini C.; Cama A.; Amoroso R. Synthesis, in vitro evaluation, and molecular modeling investigation of benzenesulfonimide Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors α antagonists. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 114, 191–200. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giampietro L.; Laghezza A.; Cerchia C.; Florio R.; Recinella L.; Capone F.; Ammazzalorso A.; Bruno I.; De Filippis B.; Fantacuzzi M.; Ferrante C.; Maccallini C.; Tortorella P.; Verginelli F.; Brunetti L.; Cama A.; Amoroso R.; Loiodice F.; Lavecchia A. Novel phenyldiazenyl fibrate analogues as PPARα/γ/δ pan-agonists for the amelioration of metabolic syndrome. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 545–551. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. E.; Stanley T. B.; Montana V. G.; Lambert M. H.; Shearer B. G.; Cobb J. E.; McKee D. D.; Galardi C. M.; Plunket K.; Nolte R. T.; Parks D. J.; Moore J. T.; Kliewer S. A.; Willson T. M.; Stimmel J. B. Structural basis for antagonist-mediated recruitment of nuclear co-repressors by PPARα. Nature 2002, 415, 813–817. 10.1038/415813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gampe R. T. Jr; Montana V. G.; Lambert M. H.; Miller A. B.; Bledsoe R. K.; Milburn M. V.; Kliewer S. A.; Willson T. M.; Xu H. E. Asymmetry in the PPARγ/RXRα crystal structure reveals the molecular basis of heterodimerization among nuclear receptors. Mol. Cell 2000, 5, 545–555. 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes C. R.; Sinha S. K.; Ganguly H. K.; Bai S.; Yap G. P. A.; Patel S.; Zondlo N. J. Insights into thiol-aromatic interactions: a stereoelectronic basis for S-H/π interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 1842–1855. 10.1021/jacs.6b08415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. E.; Lambert M. H.; Montana V. G.; Plunket K. D.; Moore L. B.; Collins J. L.; Oplinger J. A.; Kliewer S. A.; Gampe R. T. Jr.; McKee D. D.; Moore J. T.; Willson T. M. Structural determinants of ligand binding selectivity between the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 13919–13924. 10.1073/pnas.241410198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.