Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to understand the knowledge, beliefs, barriers, and behaviors of mental health professionals about physical activity and exercise for people with mental illness.

Methods:

The Portuguese version of The Exercise in Mental Illness Questionnaire was used to assess knowledge, beliefs, barriers, and behaviors about exercise prescription for people with mental illness in a sample of 73 mental health professionals (68.5% women, mean age = 37.0 years) from 10 Psychosocial Care Units (Centros de Atenção Psicossocial) in Porto Alegre and Canoas, state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Results:

Most of respondents had received no formal training in exercise prescription. Exercise ranked fifth as the most important treatment, and most of the sample never or occasionally prescribed exercise. The most frequently reported barriers were lack of training in physical activity and exercise prescription and social stigma related to mental illness. Professionals who themselves met recommended physical activity levels found fewer barriers to prescribing physical activity and did so with greater frequency.

Conclusion:

Exercise is underrated and underused as a treatment. It is necessary to include physical activity and exercise training in mental health curricula. Physically active professionals are more likely to prescribe exercise and are less likely to encounter barriers to doing so. Interventions to increase physical activity levels among mental health professionals are necessary to decrease barriers to and increase the prescription of physical activity and exercise for mental health patients.

Keywords: Mental health, physical exercise, health professionals, psychosocial support center, barriers

Introduction

Mental illnesses are highly prevalent worldwide: one in four people will receive a psychiatric diagnosis in their lifetime.1,2 Pharmacological treatments are considered first-line treatment strategies for most psychiatric diagnoses, including affective and psychotic disorders. Although multiple pharmacological approaches can be formulated, in some cases, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants, the short term-benefits are only modest.3 For example, compared to placebo, the odds of clinical response of different pharmacological antidepressants range from 1.37 to 2.13.3 Moreover, antipsychotics are associated with substantial weight gain.4 Together with other lifestyle factors, such as low levels of physical activity (PA),5-8 medication use can contribute to a higher prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases, such as diabetes, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases, and to lower life expectancy in people with mental illness.9

PA and exercise (a structured, systematic subset of PA designed to maintain or improve one or more physical capacities) have been proposed as complementary therapeutic approaches in mental illness treatment guidelines in many European countries.10-12 However, for the most part Brazilian guidelines do not consider the role of PA and exercise in mental health treatment. The benefits of PA and exercise on mental health symptoms, such as depression,13,14 anxiety,15,16 and psychosis are well known.17 In addition to mental health benefits, exercise can attenuate antipsychotic-induced weight gain and improve cardiometabolic profiles in people with mental illness.9,12 More importantly, exercise can improve cardiorespiratory fitness, an independent predictor of all-cause mortality.18

In Brazil, exercise prescription and supervision are roles usually associated with exercise professionals.19 However, encouraging a healthier lifestyle is the duty of all mental health professionals (MHP) involved in patient care. Thus, all MHP working with patients and their caregivers should be engaged in and possess sufficient knowledge to encourage and facilitate PA.

The recommendation or prescription of exercise by MHP varies across different conditions and cultures. For example, about 87% of mental health staff promote PA to their patients in France and Belgium,20 about 67.7% recommend exercise to children and adolescents with depression in Australia,21 and about 96% of nurses and occupational therapists recommend exercise at least occasionally to their patients in Uganda.22 In addition, the barriers to exercise prescription faced by MHP can vary across different settings and cultures. In Australia, the fragmentation of roles, prioritization of other tasks, lack of time, limited resources,23 and lack of specific training24 were the most commonly reported barriers to exercise prescription, while medication side effects and the social stigma surrounding mental illness were the most commonly reported barriers in Uganda.22 To the best of our knowledge, no study conducted in a middle-income country has evaluated the recommendation and prescription of exercise to people with mental illness or has assessed barriers to exercise prescription or participation.

Previous evidence suggests that mental health nurses without formal training in exercise prescription tend not to prescribe or recommend exercise to their patients.25 However, there is a lack of data on how MHP perceive PA and exercise as a complementary tool, as well as their own and their patients’ barriers to an active lifestyle in middle-income countries. Due to these gaps, the aims of the present study were to evaluate knowledge, application, barriers, beliefs, including the importance, risks, and benefits, and correlates associated with exercise prescription and recommendation by MHP to people with mental illness in a middle-income country.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included MHP working in Psychosocial Care Units (Centros de Atenção Psicossocial ‐ CAPs). CAPs provide mental health treatment to community-dwelling individuals with mental illness in Brazil. CAPs can have a multidisciplinary team consisting of physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, exercise professionals (physical therapists and physical educators), and others. The study invited all MHP working in 10 of 13 CAPs in the two largest cities (Canoas and Porto Alegre) of the metropolitan region of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Three CAPs were not included because (1) they could not provide ethics committee approval in time to perform data collection (n=2), and (2) it was impossible to reach the person in charge to obtain approval for data collection (n=1).

The study was conducted between February and March of 2018. After approval was granted, one researcher (EK) visited the CAPs and applied the questionnaires to the MHP.

Potential participants were informed about the objectives, justifications, benefits and the voluntary nature of participation in this study. Participant confidentiality was assured, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to completing the survey.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

MHP eligible for inclusion had an undergraduate degree in any health area, including physicians, nurses, exercise professionals, social workers, occupational therapists, and psychologists, or had a technical degree, such as nurse technicians. The participants had worked for a minimum of six months at CAPs for adults and provided written informed consent. MHP who worked at CAPs for children or who specialized in alcohol and drug treatment, or those who were on any type of leave or vacation during the data collection period were not included in the study.

Procedures

Participant knowledge about exercise in people with mental illness was evaluated with the Portuguese version of The Exercise in Mental Illness Questionnaire (EMIQ).26 The instrument consists of six domains: The exercise knowledge domain includes 10 items on formal training in exercise prescription and the physical and mental health benefits of exercise. The beliefs about exercise and mental illness domain includes eight questions that rank the perceived importance of exercise compared to 10 other treatments (medication, social support, electroconvulsive therapy, phototherapy, family therapy, social skills training, behavioral cognitive therapy, and vocational rehabilitation. The exercise prescription behaviors domain includes seven questions on the frequency and manner of exercise prescription. The barriers to exercise prescription domain includes 23 items, including the main barriers identified in the literature to exercise prescription for people with mental illness. This domain is further subdivided into sections on the respondents’ perceived barriers to prescribing exercise for people with mental illness and the professionals’ perception of barriers to exercise that their patients experience. For questions 3 to 17 and 26 to 48, a five-point Likert scale was used, in which 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Higher scores indicate a higher level of agreement. The scores for each barrier subsection were summed, and an overall score for the two domains was calculated. Higher scores indicate more barriers. The personal PA habits domain includes seven items on the respondents’ PA level, and each respondent’s PA level was determined from their answers. Participants who got 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA per week were considered active. The EMIQ also examines the frequency of exercise prescription with a single item: Do you prescribe exercise for persons with a mental disorder? The four possible answers are: never, occasionally, most of the time, and always. The final domain collected demographic data.

This questionnaire also allowed participants to rank what they perceived as the most important types of therapy for mental health patients. The instrument was developed and validated in English.26 A translation to Portuguese was performed according to International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research procedures27 (the translated version is available upon request).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the means, standard deviations (SD), and frequencies (n [%]). The barrier scores were calculated as follows: strongly disagree = 1 point; disagree = 2 points; neither agree nor disagree = 3 points; agree = 4 points; and strongly agree = 5 points. The total barrier score consisted of the sum of the barriers to exercise prescription score and the perceived patient barriers score and were categorized according to frequency of PA and exercise prescription. An independent t-test was used to compare differences in continuous measures (age, years working in the field, total barrier score), and a chi-square test was used to compare proportions in categorical measures (sex, proportion of participants achieving PA recommendations) between those who never prescribe exercise vs. those who prescribe exercise occasionally, most of the time, or always. Pearson or Spearman correlations (for normally and non-normally distributed data, respectively) were also conducted to test the association between exercise prescription frequency and the participants’ total barrier score and PA level. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 22. Statistical significance was considered an alpha level < 0.05.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Centro Universitário La Salle (CAAE 76645017.6.0000.5307) and the municipal research ethics committees of Porto Alegre and Canoas.

Results

Of the potentially eligible participants, 73 (mean age = 37.0 [10.0] years, women n=50 [68.5%]) of 95 (76.8%) completed and returned the questionnaire. The participants were mostly nurses (n=25, 34.3%) or nurse technicians (n=21, 28.8%). The mean time the participants had worked in the mental health area was 9.6 years (8.0). A specialization course was the highest level of education for most of the participants (n=33, 45.2%), and most worked full time (n=33, 45.2%). Detailed information about the participants is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and personal characteristics of the participants.

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Women | 50 (68.5) |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 37.0 (10.0) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 25 (34.2) |

| Widow | 2 (2.7) |

| Cohabiting | 11 (15.1) |

| Divorced | 11 (15.1) |

| Single | 24 (32.9) |

| Profession | |

| Specialized physician (psychiatrist or other type) | 5 (6.8) |

| Psychologist | 10 (13.7) |

| General practitioner | 4 (5.5) |

| Occupational therapist/recreationist/ physiotherapist | 1 (1.4) |

| Nurse technician | 21 (28.8) |

| Nurse | 25 (34.3) |

| Social worker | 6 (8.2) |

| Exercise professional | 1 (1.4) |

| Time working in the field, years, mean (SD) | 9.6 (8.0) |

| Time since obtaining the highest level of education, years, mean (SD) | 7.23 (7.1) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 33 (45.2) |

| Part-time | 32 (43.8) |

| Casual | 2 (2.7) |

| Other | 6 (8.2) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Primary education | 1 (1.4) |

| Secondary education | 23 (31.5) |

| Higher education | 14 (19.2) |

| Specialization course | 33 (45.2) |

| Master degree | 2 (2.7) |

| Doctorate degree | 0 (0) |

Data presented as n (%), unless otherwise specified.

SD = standard deviation.

Knowledge

Most of the participants (n=67, 92%) reported receiving no formal training in exercise prescription (e.g., an undergraduate degree in physical education, physical therapy, etc. or a graduate degree or continuing education in a related field). Of the six participants who reported receiving some formal training, two (33%) rated their knowledge of exercise prescription as very low, one (16.7%) as low, one (16.7%) as average, and two (33%) as good. Three of these six (50%) professionals described themselves as having much or very much confidence in prescribing exercise to people with mental illness.

Beliefs

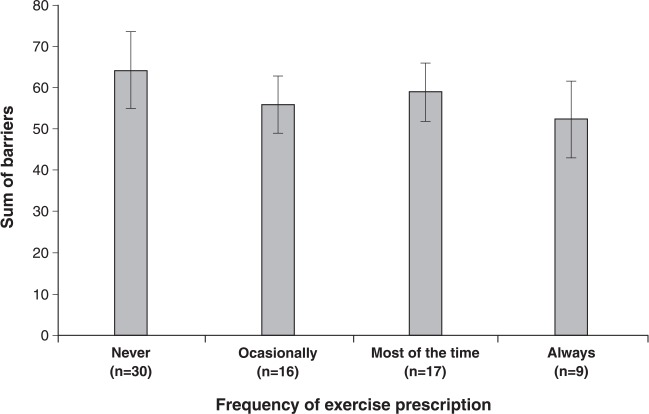

According to the respondents, the most beneficial treatments were: 1) medication (25%, n=19); 2) social support (19%, n=14); 3) family therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy (both 7%, n=5); 4) social skills training and exercise (both 1%, n=1). PA was considered the fifth most important intervention (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mental health professionals’ ranking of the importance of physical activity as a mode of therapy for people with mental illness.

Behavior

Thirty participants (41.1%) reported that they never prescribe PA, 16 participants (21.9%) stated that they occasionally prescribe it, 17 participants (23.3%) reported prescribing it most of the time, and nine participants (12.3%) always prescribe it. One participant (0.4%) did not answer the question.

Barriers

The three most frequently reported barriers to exercise prescription by MHP were: 1) “Prescribing exercise to people with a mental illness is best left to exercise professionals, such as exercise physiologists or a physical therapists,” to which 53 (72.6%) of the participants responded agree or strongly agree; 2) “I don’t know how to prescribe exercise to people with a mental illness,” to which 28 (38.3%) participants responded agree or strongly agree; and 3) “I’m concerned they might get injured while exercising,” to which 18 (24.7%) participants responded agree or strongly agree (Table 2).

Table 2. Mental health professionals’ level of agreement with statements about barriers to prescribing exercise to people with mental illness.

| Statement | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Their mental health makes it impossible for them to participate in exercise | 26 (35.6) | 34 (46.6) | 9 (12.3) | 4 (5.5) | 0 (0) |

| I’m concerned exercise might make their condition worse | 24 (32.9) | 35 (47.9) | 11 (15.1) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| I am not interested in prescribing exercise to people with a mental illness | 25 (34.2) | 31 (42.5) | 14 (19.2) | 3 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| I don’t believe exercise will help people with mental illness | 38 (52.1) | 27 (37.0) | 3 (4.1) | 4 (5.5) | 1 (1.4) |

| Their physical health makes it impossible for them to participate in exercise | 12 (16.4) | 32 (43.8) | 19 (26.0) | 9 (12.3) | 0 (0) |

| I’m concerned they might get injured while exercising | 3 (4.1) | 31 (42.5) | 20 (27.4) | 17 (23.3) | 1 (1.4) |

| People with a mental illness won’t adhere to an exercise program | 13 (17.8) | 38 (52.1) | 19 (26.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| My workload is already too excessive to include prescribing exercise to people with a mental illness | 15 (20.5) | 38 (52.1) | 17 (23.3) | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

| Prescribing exercise to people with mental illness is not part of my job | 12 (16.4) | 29 (39.7) | 16 (21.9) | 14 (19.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| I don’t know how to prescribe exercise to people with a mental illness | 3 (4.1) | 21 (28.8) | 19 (26.0) | 25 (34.2) | 3 (4.1) |

| Prescribing exercise to people with a mental illness is best left to exercise professionals, such as exercise physiologists or a physical therapists | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | 16 (21.9) | 34 (46.6) | 19 (26.0) |

Data presented as n (%).

In the respondents’ perception, the most prevalent barriers to exercise participation by their patients were: 1) “There is too much stigma attached to having a mental illness,” to which 52 (72.2%) participants responded agree or strongly agree; 2) “There are too many side effects from the medications,” to which 34 (46.5%) participants responded agree or strongly agree; and 3) “My friends or family won’t exercise with me,” to which 26 (35.6%) participants responded agree or strongly agree, as shown in Table 3

Table 3. Mental health professionals’ level of agreement with statements about barriers people with mental illness have to participating in exercise.

| Statement | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Neither agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am too unwell to exercise | 5 (6.8) | 28 (38.4) | 24 (32.9) | 15 (20.5) | 1 (1.4) |

| It takes too much time | 6 (8.2) | 42 (57.5) | 13 (17.8) | 12 (16.4) | 0 (0) |

| There is too much stigma attached to having a mental illness | 0 (0) | 11 (15.1) | 9 (12.3) | 43 (58.9) | 9 (12.3) |

| I don’t know what I should do | 1 (1.4) | 20 (27.4) | 26 (35.6) | 22 (30.1) | 3 (4.1) |

| My friends or family won’t exercise with me | 2 (2.7) | 18 (24.7) | 27 (37.0) | 25 (34.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| There are too many side effects from the medications | 1 (1.4) | 11 (15.1) | 26 (35.6) | 32 (43.8) | 2 (2.7) |

| I lack the confidence to perform any exercise | 0 (0) | 29 (39.7) | 27 (37.0) | 16 (21.9) | 1 (1.4) |

| I’m too fat to exercise | 8 (11.0) | 34 (46.6) | 16 (21.9) | 14 (19.2) | 1 (1.4) |

| I am afraid I will get hurt | 3 (4.1) | 28 (38.4) | 24 (32.9) | 17 (23.3) | 1 (1.4) |

| I have many physical health problems | 4 (5.5) | 26 (35.6) | 30 (41.1) | 13 (17.8) | 0 (0) |

| There is no safe place for me to exercise | 5 (6.8) | 37 (50.7) | 22 (30.1) | 9 (12.3) | 0 (0) |

| I don’t have any equipment to do exercise with | 4 (5.5) | 35 (47.9) | 21 (28.8) | 12 (16.4) | 1 (1.4) |

Data presented as n (%).

PA levels and recommendations

Overall, the participants themselves spent a total of 115.04 (175.37) minutes per week in vigorous PA, 71.12 (131.15) minutes in moderate PA, and 490.30 (1,158.14) minutes walking. The average time spent sitting was 377.63 (200.60) minutes per day. A total of 39 (53.4%) participants met public health PA level recommendations.

Correlates of exercise prescription

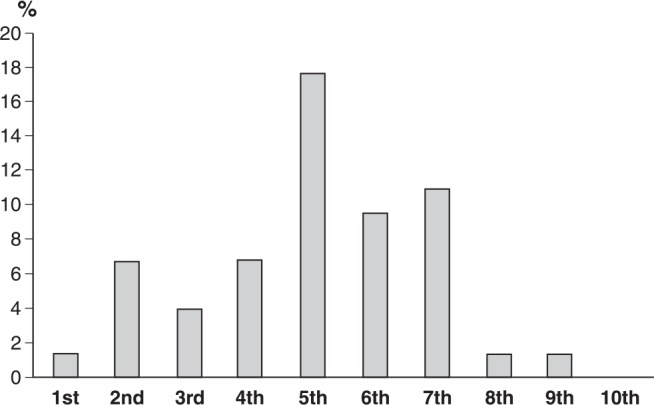

MHP who never prescribed PA and exercise did not differ from the others in age (mean = 37.79 [9.1] years vs. 36.49 [10.8] years, t = -0.516, p = 0.60) or time working in the field (mean = 9.76 [7.05] vs. 9.53 [8.5], t = -0.113, p = 0.91 years). The frequency of PA and exercise prescription did not differ by gender (30 [61.2%] women vs. 11 [57%] of men prescribe exercise, χ2 = 0.149, p = 0.928). However, those who never prescribed PA or exercise were more likely not to meet recommended PA levels themselves (MHP who met PA recommendations and prescribed PA and exercise = 27 (67.5%) vs. MHP who did not meet PA recommendations and prescribed PA and exercise = 12 (40%), χ2 = 5.25, p = 0.029). The mean number of perceived barriers according to exercise prescription frequency is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sum of the mean of barriers to exercise prescription.

Meeting PA level recommendations was inversely associated with the total barriers (r = -0.31, p = 0.04), the sum of barriers to exercise prescription (r = -0.26, p = 0.03), and the sum of barriers to patient exercise participation (r = -0.32, p = 0.009).

Discussion

The present study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first in a middle-income country to use the EMIQ to evaluate the knowledge, beliefs, barriers, and behaviors of MHP regarding exercise for people with mental illness. Its main findings are: 1) most MHP have never received any formal training in exercise prescription; 2) among the various existing therapies used for treatment, medication is perceived as the most efficient, while PA and exercise were ranked as the fifth most important intervention; 3) about 41% of workers never prescribe exercise, and only 12% always prescribe it; 4) in the respondents’ view, the most common barriers to PA that patients experience were: “There is too much stigma attached to having a mental illness,” “There are too many side effects from the medications,” and “My friends or family won’t exercise with me,” whereas the barriers the respondents reported in relation to their prescription behavior were: “Prescribing exercise to people with mental illness is best left to exercise professionals such as exercise physiologists or physical therapists,” “I don’t know how to prescribe exercise to people with a mental illness,” and “I’m concerned they might get injured while exercising”; 5) only about half of the respondents met recommended PA levels; and 6) more active respondents prescribed PA and exercise more often and perceived fewer barriers to prescribing it.

Most participants have never received formal training in PA and exercise prescription and, of the six that did, only three felt very much confidence in prescribing it. This is expected, since the sample mostly consisted of nurses and nurse technicians, and PA is not part of their curriculum. Exercise was ranked as the fifth most important therapeutic approach by the respondents, while medication ranked first, followed by social support. This finding corroborates studies in other cultures. For example, in the United Kingdom most nurses reported knowing that exercise is important, but were more concerned with pharmaceutical treatments.28 This finding is expected, since international guidelines recommend medications as the first-line treatment for most mental illness.11

Our data show that about to 40% of mental health workers never prescribe PA and exercise, and only 12% always prescribe it. Interestingly, the most active professionals are more likely to prescribe exercise. Our findings corroborate other studies29-31 that found an association between self-reported PA and exercise prescription. These findings suggest that MHP are more likely to encourage healthy behaviors in their patients if they themselves engage in such behaviors.31 Therefore, encouraging lifestyle changes in MHP can result in greater adherence to PA recommendations and fewer barriers to encouraging PA in their patients. On the other hand, previous studies have shown that PA or self-reported physical fitness were not associated with exercise recommendation among psychiatrists in Australia and New Zealand.32,33 However, members of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners recommend exercise more frequently than Brazilian MHP (89 vs. 36%31). This could be due to the fact that exercise has been incorporated into the stepped care approach of the Australian guidelines for depression treatment,34 while Brazilian guidelines for major depression do not mention exercise.11,35

The most prevalent barriers to prescribing exercise to people with a mental illness were the belief that it is best left to exercise professionals or physical therapists and the perceived lack of necessary skills to properly prescribe it. The first of these barriers may be related to ethics, since in Brazil only those with a degree in physical education or physical therapy are legally permitted to prescribe exercise. Although exercise prescription is indeed the role of exercise professionals, encouraging, recommending and supporting healthier lifestyles is the responsibility of all health professionals and must be performed in a multidisciplinary way. This is an important task, since patients who exercise reported that the most important factor in their decision to do so was to prior encouragement by a professional.36 Similar findings have been reported in other countries, such as Australia, where exercise physiologists, physical therapists, general practitioners, and to a lesser extent, occupational therapists can prescribe exercise,37 although psychiatrists found barriers to doing so. It should be pointed out that although 90% of psychiatrists in Australia and New Zealand have recommended exercise, over half do not utilize exercise referral processes.32 Besides the limited knowledge of how to prescribe exercise, other barriers include unclear diagnosis, lack of organizational and financial support, competing priorities and integration of the healthcare team.38

According to the present sample of Brazilian MHP, the most common barriers to patient participation in PA are social stigma, medication side effects, and lack of support from their family and friends. These results are similar to those of other studies. Glover et al.39 found that the main reasons patients did not participate in PA were: the side effects of psychiatric drugs, external physical comorbidities, and the treatment’s focus on symptoms of the disease. Similarly, medication side effects and social stigma were the most common barriers to PA reported by Ugandan mental health patients.22 To overcome these barriers, MHP should provide patients with the necessary information, support, and encouragement to change.11,29-35

This study has some limitations. Although the instrument went through a translation and transcultural adaption process, the psychometric proprieties of the Portuguese language version were not tested. Moreover, the instrument only measures the frequency of prescription, not the frequency of recommendation. Semantic differences could have thus played a role, since more professionals may have recommended, but not prescribed, exercise to their patients. The sample consisted of MHP working in the two largest cities in the metropolitan area of Porto Alegre, which may not be representative of other regions in Brazil. However, we included 73 out of the 95 (76.8%) MHP in the included CAPs, which suggests that this data is quite representative. Finally, we could not explore the differences between MHP classes due to the small number of participants from each profession. Future studies should investigate these limitations and include a greater number of MHP from all areas. Social desirability can be a factor in behavioral studies, so it is possible that the MHP who volunteered to participate in the study prescribed exercise more often. However, it is unlikely that this bias significantly affected our study, since most of the participants reported not prescribing exercise to their patients. Finally, given that this was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to establish causal relationships.

In conclusion, most of the MHP in this sample do not prescribe or recommend exercise to their patients. Their lack of knowledge about how to prescribe or recommend exercise is a barrier to increasing PA levels in their patients, and they considered that the stigma associated with mental illness is a further barrier to PA. In Brazil, prescribing exercise is considered the domain of exercise professionals. However, due to the importance of exercise in mental illness treatment, all MHP should acquire sufficient knowledge to be able recommend a more active lifestyle for their patients. Physically active MHP prescribe more PA and exercise and encourage lifestyle changes, and increasing PA levels among MHP may be an efficient strategy for overcoming barriers to exercise prescription.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Kleemann E, Bracht CG, Stanton R, Schuch FB. Exercise prescription for people with mental illness: an evaluation of mental health professionals’ knowledge, beliefs, barriers, and behaviors. Braz J Psychiatry. 2020;42:271-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0547

References

- 1.Steel Z, Marnane C, Iranpour C, Chey T, Jackson JW, Patel V, et al. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis 1980-2013. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:476–93. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet (London, England). 2013;382(9904):1575–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391:1357–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spertus J, Horvitz-Lennon M, Abing H, Normand SL. Risk of weight gain for specific antipsychotic drugs: a meta-analysis. NPJ Schizophr. 2018;4:12. doi: 10.1038/s41537-018-0053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, Hallgren M, et al. Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a global systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry. 2017;16:308–15. doi: 10.1002/wps.20458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuch F, Vancampfort D, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Ward P, Reichert T, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;210:139–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch F, Rosenbaum S, De Hert M, Mugisha J, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behavior in people with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;201:145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Gaughran F, et al. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr Res. 2016;176:431–40. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, Siskind D, Rosenbaum S, Galletly C, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:675–712. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallgren M, Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Lundin A, Jääkallio P, Forsell Y. Treatment guidelines for depression: greater emphasis on physical activity is needed. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;40:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carneiro LF, Mota MP, Schuch F, Deslandes A, Vasconcelos-Raposo J. Portuguese and Brazilian guidelines for the treatment of depression: exercise as medicine. Braz J Psychiatry. 2018;40:210–1. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2017-2272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J, Veronese N, Solmi M, et al. EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: a meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). Eur Psychiatry. 2018;54:124–44. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, Rosenbaum S, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Hallgren M, Meyer JD, Lyons M, Herring MP. Association of efficacy of resistance exercise training with depressive symptoms: meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:566–76. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordon BR, McDowell CP, Lyons M, Herring MP. The effects of resistance exercise training on anxiety: a meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2017;47:2521–32. doi: 10.1007/s40279-017-0769-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Firth J, Cosco T, Veronese N, et al. An examination of the anxiolytic effects of exercise for people with anxiety and stress-related disorders: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;249:102–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Firth J, Cotter J, Elliott R, French P, Yung AR. A systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise interventions in schizophrenia patients. Psychol Med. 2015;45:1343–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714003110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belvederi Murri M, Ekkekakis P, Magagnoli M, Zampogna D, Cattedra S, Capobianco L, et al. Physical exercise in major depression: reducing the mortality gap while improving clinical outcomes. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:762. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conselho Federal de Educação Física (CONFEF) [Internet] 2019. [cited 2020 Jan 23] https://www.confef.org.br/confef/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mas S, Bernard P, Gourlan M. Determinants of physical activity promotion by smoking cessation advisors. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101:1942–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Radovic S, Melvin GA, Gordon MS. Clinician perspectives and practices regarding the use of exercise in the treatment of adolescent depression. J Sports Sci. 2018;36:1371–7. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2017.1383622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vancampfort D, Stanton R, Probst M, De Hert M, van Winkel R, Myin-Germeys I, et al. A quantitative assessment of the views of mental health professionals on exercise for people with mental illness: perspectives from a low-resource setting. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19:2172–82. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i2.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Happell B, Scott D, Platania-Phung C, Nankivell J. Nurses' views on physical activity for people with serious mental illness. Ment Health Phys Act. 2012;5:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Way K, KannisL, Lastella M, Lovell GP. Mental health practitioners’ reported barriers to prescription of exercise for mental health consumers. Ment Health Phys Act. 2018;14:52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stanton R, Happell B, Reaburn P. Investigating the exercise-prescription practices of nurses working in inpatient mental health settings. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2015;24:112–20. doi: 10.1111/inm.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanton R, Happell B, Reaburn P. The development of a questionnaire to investigate the views of health professionals regarding exercise for the treatment of mental illness. Ment Health Phys Act. 2014;7:177–82. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robson D, Haddad M, Gray R, Gournay K. Mental health nursing and physical health care: a cross-sectional study of nurses' attitudes, practice, and perceived training needs for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22:409–417. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lobelo F, de Quevedo IG. The evidence in support of physicians and health care providers as physical activity role models. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2016;10:36–52. doi: 10.1177/1559827613520120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fie S, Norman IJ, While AE. The relationship between physicians' and nurses' personal physical activity habits and their health-promotion practice: a systematic review. Health Educ J. 2013;72:102–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fibbins H, Ward PB, Watkins A, Curtis J, Rosenbaum S. Improving the health of mental health staff through exercise interventions: a systematic review. J Ment Health. 2018;27:184–91. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1437614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fibbins H, Czosnek L, Stanton R, Davison K, Lederman O, Morell R, et al. Self-reported physical activity levels of the 2017 Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) conference delegates and their exercise referral practices. J Ment Health. 2018 Oct 15:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1521935. doi: http://10.1080/09638237.2018.1521935. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stanton R, Franck C, Reaburn P, Happell B. A pilot study of the views of general practitioners regarding exercise for the treatment of depression. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51:253–9. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malhi GS, Outhred T, Hamilton A, Boyce PM, Bryant R, Fitzgerald PB, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: major depression summary. Med J Aust. 2018;208:175–80. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Associação Brasileira de Psiquiatria, Associação Brasileira de Medicina Física e Reabilitação, Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina de Família e Comunidade . Depressão unipolar: tratamento não-farmacológico [Internet]. 2011 Oct 20. [cited 2019 Nov 5] http://diretrizes.amb.org.br/_BibliotecaAntiga/depressao_unipolar_tratamento_nao_farmacologico.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelletier L, Shanmugasegaram S, Patten SB, Demers A. Self-management of mood and/or anxiety disorders through physical activity/exercise. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37:149–59. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.37.5.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pugh J, Pugh C, Savulescu J. Exercise prescription and the doctor’s duty of non-maleficence. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:1555–6. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartels S, Brunette M, Aschbrenner K, Daumit G. Implementation of a system-wide health promotion intervention to reduce early mortality in high risk adults with serious mental illness and obesity. Implement Sci. 2015;10:A15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glover CM, Ferron JC, Whitley R. Barriers to exercise among people with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2013;36:45–7. doi: 10.1037/h0094747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]