Abstract

Background:

We used a large-scale, high-throughput DNA aptamer-based discovery proteomic platform to identify circulating biomarkers of cardiac remodeling and incident heart failure (HF) in community-dwelling individuals.

Methods:

We evaluated 1895 Framingham Heart Study (FHS) participants (age 55±10 years, 54% women) who underwent proteomic profiling and echocardiography. Plasma levels of 1305 proteins were related to echocardiographic traits and to incident HF using multivariable regression. Statistically significant protein-HF associations were replicated in the HUNT (Nord-Trøndelag Health) study (n=2497, age 63±10 years, 43% women), and results were meta-analyzed. Genetic variants associated with circulating protein levels (pQTLs) were related to echocardiographic traits in the EchoGen (n=30,201) and to incident HF in the CHARGE (n=20,926) consortia.

Results:

Seventeen proteins associated with echocardiographic traits in cross-sectional analyses (FDR q-value<0.10), and 8 of these proteins had pQTLs associated with echocardiographic traits in EchoGen (P<0.0007). In Cox models adjusted for clinical risk factors, 29 proteins demonstrated associations with incident HF in FHS (174 HF events, mean follow up 19 [limits 0.2-23.7] years). In meta-analyses of FHS and HUNT, 6 of these proteins were associated with incident HF (P<3.8x10−5; 3 with higher risk: N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide, thrombospondin-2, mannose-binding lectin; and 3 with lower risk: epidermal growth factor receptor, growth differentiation factor-11/8, and hemojuvelin). For 5 of the 6 proteins, pQTLs were associated with echocardiographic traits (p<0.0006) in EchoGen, and for hemojuvelin, a pQTL was associated with incident HF (p=0.001).

Conclusions:

A large-scale proteomics approach identified new predictors of cardiac remodeling and incident HF. Future studies are warranted to elucidate how biological pathways represented by these proteins may mediate cardiac remodeling and HF risk, and to assess if these proteins can improve HF risk prediction.

INTRODUCTION

Numerous clinical factors and pathway biomarkers are associated with increased risk of developing heart failure (HF).1-4 Despite progress in understanding the pathobiology of HF, the ability to characterize precisely and modulate effectively the risk for progressing to manifest HF remains limited. Novel biomarkers are necessary to refine existing HF risk prediction methods and to identify modifiable biological pathways related to HF development and progression that can be targeted to reduce disease burden.

Previous investigations of protein biomarkers of HF have primarily relied on assays specific to single proteins. A small number of studies have applied liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry-based platforms to perform proteomic profiling in HF samples.5, 6 Biosample throughput with this technique is limited by the burden of analytic steps and the inability to measure low-abundance proteins without extensive sample preparation.7 Consequently, prior investigations have primarily focused on select biomarkers of increased HF risk; few studies have measured a large panel of proteins to assess the activity of biological pathways that may indicate either higher or lower HF risk.8

Technological advances in aptamer-based proteomic arrays now enable systematic profiling of the plasma proteome. These methods have been employed to identify novel biomarkers of cardiovascular risk in individuals with established coronary heart disease or HF,9-12 subclinical atherosclerosis,10 myocardial injury and cardiovascular risk factors,10, 13 and early drug toxicity.14

We used a discovery proteomics approach to assay 1305 plasma protein levels using the SomaScan® platform (SomaLogic, Boulder, CO) that we then related to echocardiographic traits and incident HF in the Framingham Heart Study (FHS). Candidate proteins that were associated with incident HF in FHS were also analyzed in the HUNT cohort (the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study), and the results were meta-analyzed. We further explored genomic loci for proteins with demonstrable associations for their relations to cardiac remodeling and incident HF in large independent genetic consortia.

METHODS

Data sharing

The data supporting the study findings will be made available upon reasonable request. Framingham Heart Study data are available to research community upon request (https://www.framinghamheartstudy.org/fhs-for-researchers/data-sharing-principles/).

Study samples

The design of the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) Offspring cohort has been described.15 For the present investigation, we included a total of 1913 individuals from the fifth examination cycle in whom aptamer-based proteomic profiling and routine echocardiography were performed. This was completed in two different “batches.” In batch one 1,129 proteins (“1.1k”) were profiled in 821 individuals. As a result of platform enhancements that occurred in the interval between the first and second set of samples being run, batch 2 included an expanded panel of 1305 proteins (“1.3k”), which was assayed in 1092 participants. For the cross-sectional associations of protein biomarkers and echocardiographic traits, we excluded individuals with missing covariates (n=18), and those with missing echocardiographic measures (n= 59-482 depending on trait). For prospective analyses evaluating the associations of proteins with incident HF, we additionally excluded individuals with prevalent HF (n=9). All participants provided informed written consent, and all study protocols were approved by the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

The HUNT Study (Nord-Trøndelag Health Study) is a population-based cohort in Norway comprising >150,000 participants from the Nord-Trøndelag County.16 The current study sample included individuals from the third survey (HUNT3; enrollment period 2006-2008). Proteomic profiling was performed in 1067 participants with an incident primary cardiovascular event and in 1448 individuals randomly selected from the full HUNT3 cohort (n=50,807). After excluding individuals with prevalent HF (n=2) and missing covariates (n=16), a total of 2497 participants were available for analysis. All individuals provided informed written consent and the study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK South-East C 2018/784).

Details of covariate measurement, echocardiographic image acquisition, and outcome ascertainment are available in the Supplemental Methods.

Proteomic profiling

Proteomic profiling using the SomaScan system has been described.9, 10, 17 In FHS, plasma samples were collected in citrate-treated tubes, which were then centrifuged within 15 minutes at 2000g for 10 min and the supernatant plasma was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C without freeze thaw cycles until assayed. Proteomic profiling was performed on thawed plasma samples using the SomaScan single-stranded DNA aptamer-based platform using SOMAmer® reagents.10 Intra-assay coefficients of variation (CVs) had a median of 5.20 (25th percentile 4.06, 75th percentile 6.77) for batch 1 and 3.56 (25th percentile 2.80, 75th percentile 4.90) for batch 2. Inter-assay CVs were 11.81 (25th percentile 8.82, 75th percentile 17.17) for batch 1 and 7.52 (25th percentile 4.71, 75th percentile 12.97) for batch 2. The median interclass correlation in FHS samples was >0.95.10

In HUNT 3, plasma samples were collected in EDTA tubes, and the samples were centrifuged, plasma aspirated and frozen at −80 °C ≤24 hours after blood draw. Never-thawed samples were shipped to SomaLogic, Boulder, CO and proteomic profiling was performed using a SOMAscan panel of approximately 5000 proteins (version 4).

Statistical analysis

The analytical steps are summarized in Figure 1. Baseline characteristics were displayed for both samples and were compared using two-tailed t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for dichotomous variables. Protein concentrations were log-transformed, standardized within batch, and then pooled and normalized to a mean value of 0 and standard deviation of 1 unit (separately in the two study samples) using the Blom rank-based inverse-normal method.18 These values were then regressed on assay plate ID, and the residuals from these regressions were used for analysis to account for batch effects.

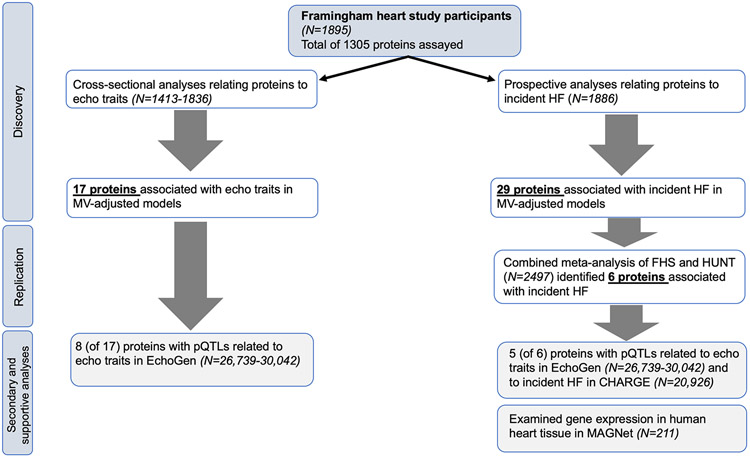

Figure 1. Flowchart of the analytical approach.

Abbreviations: MV, multivariable; pQTLs, protein quantitative trait loci; HF, heart failure; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; HUNT, Nord-Trøndelag Health Study; CHARGE, Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology; MAGNet, Myocardial Applied Genomics Network

We used multivariable-adjusted linear regression models to relate each protein (independent variable) to four primary (ln[left ventricular mass (LVM)], left ventricular diastolic diameter [LVDD], left atrial dimension [LAD], aortic root diameter [AoR]) and two secondary (left ventricular wall thickness [LVWT], fractional shortening [FS]) echocardiographic traits (dependent variables). Models were initially adjusted for age, sex, and height, and were then adjusted for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, total/HDL cholesterol, diabetes, current smoking, and prior myocardial infarction. A false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.10 (using the Benjamini-Hochberg method) was considered suggestive of statistical significance.19

We used Cox proportional hazards regression models to relate each protein to incident HF. Hazard ratios were expressed as the relative hazard for a one standard deviation increment in the transformed and normalized protein level. We confirmed that the proportionality of hazards assumption was met for each protein that was statistically significantly associated with incident HF by testing the interaction of the natural log of the time to incident HF * protein concentration (P >0.05/number of statistically significant proteins). Models were adjusted initially for age and sex, and then additionally adjusted for BMI, systolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medications, total/HDL cholesterol, diabetes, current smoking, prior myocardial infarction, and interim myocardial infarction between the baseline examination and the end of follow-up (myocardial infarction was included as a time-varying covariate). This approach was used to assess the effect of clinical covariates and the degree to which they attenuate associations of our proteins of interest. For this discovery stage, statistical significance was determined using a FDR threshold of <0.10. This value was considered to be conservative in limiting type I error due to anticipated correlation among proteins in the SomaScan discovery platform. For proteins that were only measured in 1 batch, we considered associations with hazard ratios (HR) more extreme than those for proteins with FDR q-values <0.10 to be suggestive (owing to smaller sample size) and were included in the replication analyses. In secondary analyses, we compared the baseline level of each protein between groups that developed HF with preserved versus reduced ejections fractions (HFpEF and HFrEF). We used the rank-normalized protein levels and independent two-sample t-tests (with a nominal P-value threshold of <0.0017 [0.05/29 proteins]).

Proteins that were associated with incident HF in multivariable-adjusted models in the FHS were then related to incident HF in HUNT using the same covariates. Results from FHS and HUNT were meta-analyzed using a fixed effects model. A Bonferroni-adjusted p-value threshold of 3.8×10−5 (0.05/1305 proteins tested) was used to determine statistical significance for the meta-analysis. In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted statistically significant models relating proteins to HF also for estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Correlation matrices (heat maps) were constructed to display correlations among proteins that were associated with echocardiographic traits and incident HF. Age- and sex-adjusted partial correlations between proteins were calculated and we employed a clustering algorithm which sought to maximize the variance explained by the within-cluster first principal components across all clusters, subject to the constraint that there be 10 or fewer clusters for each direction of effect. Proteins measured in one batch only were clustered separately (proc varclus, SAS). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC) in FHS, and R (Version 1.1.453) in HUNT.

Evaluating cardiac gene expression

For proteins that were statistically significantly associated with incident HF in the meta-analyses, we compared the expression of their coding genes in human heart tissue from individuals with end-stage cardiomyopathy (n=89) and controls (n=122) from Myocardial Applied Genomics Network (MAGNet; www.med.upenn.edu/magnet).20 RNA levels were compared in the two groups using a linear model adjusting for gender and age effects. A p-value of <0.0083 (0.05/6 proteins) was considered suggestive of statistical significance.

Genetic ‘look-up’ of key proteins

We investigated whether genetic loci associated with plasma protein levels (protein quantitative trait loci [pQTLs]) might be associated with echocardiographic traits and incident HF in separate samples. Protein QTLs were identified by relating genetic variants to protein levels in FHS as previously described.17 We defined pQTLs as protein-variant associations with p <1 × 10-4. We used linear regression to relate pQTLs for the proteins associated with echocardiographic traits in FHS with echocardiographic traits in the EchoGen consortium (N=30,201; 22-26% FHS participants).21, 22 An a priori p-value threshold of <7 × 10−4 (0.05/ [17 proteins * 4 primary echocardiographic traits]) was used to indicate statistical significance. We then related pQTLs for the proteins associated with incident HF in our primary study samples to echocardiographic traits in EchoGen, and to incident HF in the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium HF Working Group23 (N= 20,926 individuals [18% FHS participants] from four international cohorts, 2526 incident HF events). A nominal p-value threshold of <0.0017 (0.05/ [6 proteins * 5 traits) was used to assess statistical significance.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the samples are displayed in Table 1. The FHS sample was middle-aged and over half of the participants were women. The replication sample in HUNT was 8 years older on average with a lower proportion of women, higher blood pressure, and a higher incidence of interim MI during the follow-up period.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study samples

| Discovery Sample | Replication Sample | Standardized differences |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | FHS (N=1895) | HUNT (N=2497) | |

| Age, years | 55±10 | 63±10 | 0.800 |

| Female sex, N (%) | 1014 (54) | 1076 (43) | 0.210 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.4±5.1 | 27.8±4.2 | 0.086 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 126±19 | 139±19 | 0.684 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 74±10 | 78±12 | 0.362 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 205±36 | 228±43 | 0.580 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 50±15 | 50±15 | 0.000 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 149 (8) | 201 (8) | 0.007 |

| Antihypertensive medication, N (%) | 376 (20) | 826 (33) | 0.304 |

| Current smoking, N (%) | 369 (19) | 577 (23) | 0.089 |

| Prevalent MI at baseline, N (%) | 44 (2.3) | 4 (0.2) | 0.196 |

| Interim MI during follow up, N (%) | 150 (8) | 516 (21) | 0.370 |

| LV mass, grams* | 163±41 | -- | -- |

| LV wall thickness, cm* | 1.9±0.3 | -- | -- |

| LV diastolic dimension, cm* | 4.7±0.5 | -- | -- |

| Left atrial dimension, cm* | 3.8±0.5 | -- | -- |

| Aortic root diameter, cm* | 3.2±0.4 | -- | -- |

| Fractional shortening, %* | 37±7 | -- | -- |

Data are reported as mean ± SD or N (%)

Means or percentages for all variables differed (P <0.05) between the two samples except for HDL cholesterol and diabetes

Standardized differences compare the difference in means of the two samples in units of the pooled standard deviation

Abbreviations: FHS, Framingham Heart Study; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MI, myocardial infarction; LV, left ventricle

Total sample size with available echocardiographic measures was as follows: LV mass (N=1424), LV wall thickness (N=1449), LV diastolic dimension (N=1434), left atrial dimension (N=1817), aortic root diameter (N=1836), fractional shortening (N=1413)

Associations with cross-sectional echocardiographic traits in FHS

In age-, sex-, and height-adjusted models, statistically significant (FDR <0.10) associations were observed between plasma levels of 106 proteins and LVM, 2 proteins and LVDD, 271 proteins and LAD, and 77 proteins and AoR (Supplemental Tables 1-4). In secondary analyses, we related proteins with additional echocardiographic traits and observed associations of 118 proteins with LVWT, and 1 protein with FS (Supplemental Tables 5-6). We evaluated the correlations among the proteins significantly related to the primary echocardiographic traits and observed substantial statistical correlation, which may indicate shared biological pathways (Supplemental Figures 1-3). Upon adjustment for clinical risk factors, we identified 17 proteins to be associated with the primary echocardiographic traits (FDR q<0.10; Table 2 and Supplemental Figure 4).

Table 2.

Associations of protein levels with echocardiographic traits in multivariable-adjusted models in FHS

| ln(LV Mass) | LV Diastolic Dimension | Left Atrial Diameter | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | β est. | SE | P-value | FDR | β est. | SE | P-value | FDR | β est. | SE | P-value | FDR |

| IGFBP-2* | 0.037 | 0.008 | 2.2E-06 | 0.003 | 0.063 | 0.015 | 0.00005 | 0.03 | ||||

| TGF-b R III | 0.023 | 0.006 | 0.00005 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| NT-proBNP* | 0.029 | 0.008 | 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.061 | 0.015 | 0.00004 | 0.03 | 0.081 | 0.014 | 1.5E-08 | 0.00002 |

| ESAM | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.0001 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| ART | 0.021 | 0.006 | 0.0002 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Leptin* | −0.040 | 0.011 | 0.0002 | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Osteopontin* | 0.026 | 0.007 | 0.0003 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| UNC5H3 | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| WFKN1 | −0.021 | 0.006 | 0.0004 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Epithelial cell kinase | 0.020 | 0.006 | 0.0005 | 0.07 | ||||||||

| RGMC | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.0007 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| SOD3* | 0.058 | 0.015 | 0.00007 | 0.03 | ||||||||

| HGF | −0.043 | 0.011 | 0.0002 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| MPIF-1 | 0.040 | 0.011 | 0.0002 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Chromogranin A* | 0.053 | 0.014 | 0.0002 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Ck-beta-8-1 | 0.037 | 0.011 | 0.0005 | 0.098 | ||||||||

| Dynactin subunit 2* | −0.061 | 0.016 | 0.0001 | 0.06 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: IGFBP-2, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 2; TGF-b R III, TGF-beta receptor type-3; NT-proBNP, N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide; ESAM, endothelial cell-selective adhesion molecule; ART, agouti-related protein; UNC5H3, netrin receptor, UNC5C; WFKN1, WAP, kazal, immunoglobulin, kunitz and NTR domain-containing protein 1; RGMC, repulsive guidance molecule C (hemojuvelin); SOD3, extracellular superoxide dismutase; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; MPIF-1, myeloid progenitor inhibitory factor 1 (C-C motif chemokine 23)

Protein levels were transformed by rank normalization to mean = 0 and standard deviation = 1 and betas in the table above reflect effect size for a 1 SD increment in transformed and normalized protein levels

Multivariable model is adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, hypertension treatment, total/HDL cholesterol, diabetes, current smoking, and prevalent myocardial infarction

False discovery rate (FDR) value <0.10 was used to determine statistical significance

No proteins were associated with aortic root diameter with FDR <0.10

Protein was measured on the SomaLogic 1.3k platform only (N=1081)

Associations with incident HF

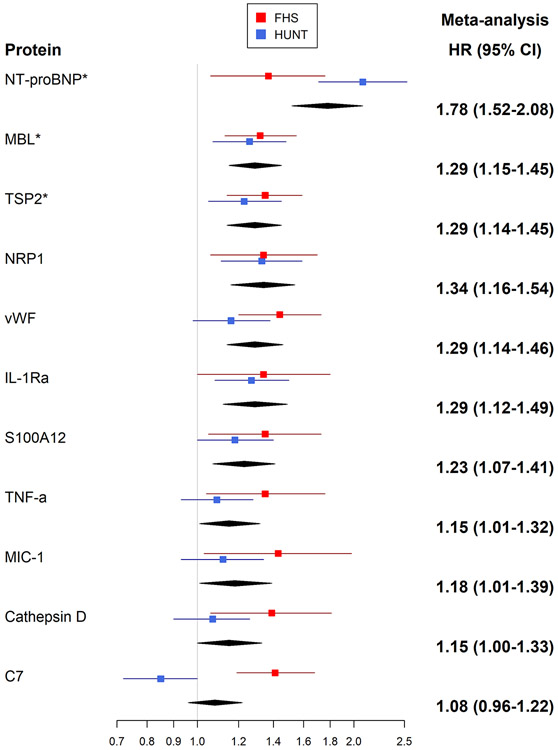

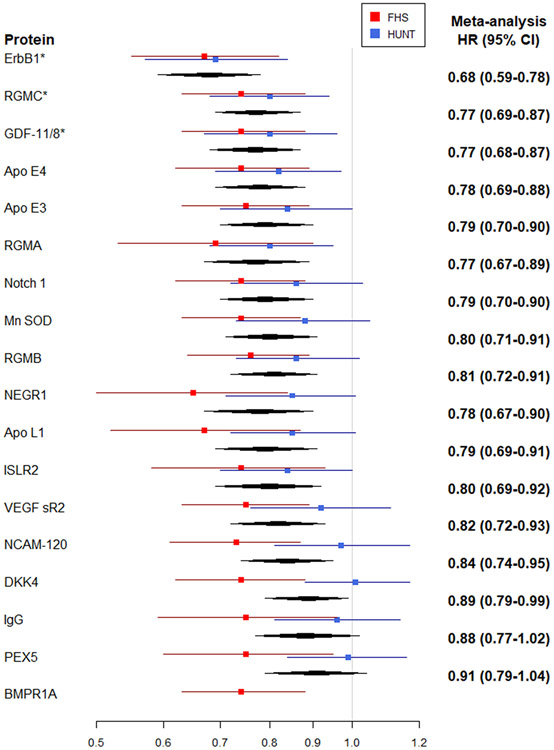

During a mean follow-up of 19 years (limits 0.2-23.7 years) in 1886 individuals free of HF at baseline, 174 new-onset HF events occurred in the FHS. In Cox models adjusted for age and sex, circulating levels of 175 proteins were associated with incident HF (FDR q <0.10; Supplemental Table 7 and Supplemental Figure 5). In models adjusted for clinical risk factors, 17 proteins were associated with HF risk (FDR q <0.10; Table 3 and Figure 2). In addition to these 17 proteins meeting the pre-specified FDR significance threshold, 12 proteins were related to incident HF with more extreme hazard ratios (effect sizes) than proteins meeting our statistical significance threshold, but with higher FDR values resulting from smaller sample sizes because they were assayed only in the 2nd batch (1.3k platform), Table 3. These 29 proteins associated with incident HF demonstrate substantial correlation among their levels (Supplemental Figure 6). Associations of additional proteins that are measured on this platform and have been previously reported to be related to HF risk are shown in Supplemental Table 8.

Table 3.

Associations of protein levels with incident heart failure in multivariable-adjusted models

| Meta-Analysis | Discovery (FHS) | Replication (HUNT) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | FDR | HR (95% CI) | P-value | Heterogeneity I2 |

| NT-proBNP* | 1.78 (1.52-2.08) | 3.5E-13 | 1.37 (1.06-1.76) | 0.02 | 0.35 | 2.08 (1.71-2.53) | 2.6E-12 | 0.85 |

| ErbB1 | 0.68 (0.59-0.78) | 4.4E-08 | 0.67 (0.55-0.82) | 0.00006 | 0.04 | 0.69 (0.57-0.84) | 0.00017 | 0.00 |

| MBL | 1.29 (1.15-1.45) | 1.2E-05 | 1.32 (1.13-1.55) | 0.0006 | 0.08 | 1.26 (1.07-1.48) | 0.0055 | 0.00 |

| RGMC | 0.77 (0.69-0.87) | 2.0E-05 | 0.74 (0.63-0.88) | 0.0008 | 0.08 | 0.80 (0.68-0.94) | 0.007 | 0.00 |

| GDF-11/8 | 0.77 (0.68-0.87) | 3.0E-05 | 0.74 (0.63-0.88) | 0.0006 | 0.08 | 0.80 (0.67-0.96) | 0.014 | 0.00 |

| TSP2 | 1.29 (1.14-1.45) | 3.1E-05 | 1.35 (1.14-1.59) | 0.0006 | 0.08 | 1.23 (1.05-1.45) | 0.013 | 0.00 |

| NRP1* | 1.34 (1.16-1.54) | 6.8E-05 | 1.34 (1.06-1.70) | 0.01 | 0.35 | 1.33 (1.11-1.59) | 0.0016 | 0.00 |

| vWF | 1.29 (1.14-1.46) | 7.6E-05 | 1.44 (1.20-1.73) | 0.00007 | 0.04 | 1.16 (0.98-1.38) | 0.093 | 0.66 |

| Apo E4 | 0.78 (0.69-0.88) | 8.9E-05 | 0.74 (0.62-0.89) | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.82 (0.69-0.97) | 0.022 | 0.00 |

| Apo E3 | 0.79 (0.70-0.90) | 0.0002 | 0.75 (0.63-0.89) | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.84 (0.70-1.00) | 0.056 | 0.00 |

| RGMA* | 0.77 (0.67-0.89) | 0.0003 | 0.69 (0.53-0.90) | 0.006 | 0.25 | 0.80 (0.68-0.95) | 0.011 | 0.00 |

| Notch 1 | 0.79 (0.70-0.90) | 0.0003 | 0.74 (0.62-0.88) | 0.0007 | 0.08 | 0.86 (0.72-1.03) | 0.094 | 0.26 |

| Mn SOD | 0.80 (0.71-0.91) | 0.0004 | 0.74 (0.63-0.87) | 0.0004 | 0.08 | 0.88 (0.73-1.05) | 0.17 | 0.47 |

| RGMB | 0.81 (0.72-0.91) | 0.0004 | 0.76 (0.64-0.89) | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.86 (0.73-1.02) | 0.082 | 0.12 |

| IL-1Ra* | 1.29 (1.12-1.49) | 0.0005 | 1.34 (1.00-1.80) | 0.05 | 0.5 | 1.27 (1.08-1.50) | 0.004 | 0.00 |

| NEGR1* | 0.78 (0.67-0.90) | 0.0007 | 0.65 (0.50-0.84) | 0.0009 | 0.09 | 0.85 (0.71-1.01) | 0.064 | 0.65 |

| Apo L1* | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | 0.001 | 0.67 (0.52-0.87) | 0.002 | 0.14 | 0.85 (0.72-1.01) | 0.063 | 0.56 |

| ISLR2* | 0.80 (0.69-0.92) | 0.002 | 0.74 (0.58-0.93) | 0.01 | 0.32 | 0.84 (0.70-1.00) | 0.047 | 0.00 |

| VEGF sR2 | 0.82 (0.72-0.93) | 0.003 | 0.75 (0.63-0.89) | 0.001 | 0.09 | 0.92 (0.76-1.11) | 0.39 | 0.60 |

| S100A12* | 1.23 (1.07-1.41) | 0.003 | 1.35 (1.05-1.73) | 0.02 | 0.37 | 1.18 (1.00-1.40) | 0.043 | 0.00 |

| NCAM-120 | 0.84 (0.74-0.95) | 0.007 | 0.73 (0.61-0.87) | 0.0006 | 0.08 | 0.97 (0.81-1.17) | 0.75 | 0.79 |

| TNF alpha* | 1.15 (1.01-1.32) | 0.04 | 1.35 (1.04-1.76) | 0.02 | 0.4 | 1.09 (0.93-1.28) | 0.31 | 0.49 |

| MIC-1* | 1.18 (1.01-1.39) | 0.04 | 1.43 (1.03-1.98) | 0.03 | 0.44 | 1.12 (0.93-1.34) | 0.25 | 0.40 |

| DKK4 | 0.89 (0.79-0.99) | 0.04 | 0.74 (0.62-0.88) | 0.0007 | 0.08 | 1.01 (0.88-1.17) | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Cathepsin D* | 1.15 (1.00-1.33) | 0.06 | 1.39 (1.06-1.81) | 0.02 | 0.35 | 1.07 (0.90-1.26) | 0.47 | 0.63 |

| IgG* | 0.88 (0.77-1.02) | 0.08 | 0.75 (0.59-0.96) | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.96 (0.81-1.14) | 0.64 | 0.61 |

| PEX5* | 0.91 (0.79-1.04) | 0.15 | 0.75 (0.60-0.95) | 0.02 | 0.37 | 0.99 (0.84-1.16) | 0.91 | 0.72 |

| C7 | 1.08 (0.96-1.22) | 0.21 | 1.41 (1.19-1.68) | 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.85 (0.72-1.00) | 0.048 | 0.94 |

| BMPR1A† | -- | -- | 0.74 (0.63-0.88) | 0.0006 | 0.08 | -- | -- | -- |

Abbreviations: NT-proBNP, N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide; ErbB1, epidermal growth factor receptor; MBL, mannose binding lectin; RGMC, repulsive guidance molecule C (hemojuvelin); GDF-11/8, growth/differential factor 11/8; TSP2, thrombospondin-2; NRP1, neuropilin 1; vWF, von Willebrand factor; Apo E4, apolipoprotein E (isoform E4); Apo E3, apolipoprotein E (isoform E3); RGMA, repulsive guidance molecule A; Mn SOD, superoxide dismutase [Mn], mitochondrial; Notch 1, neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 1; RGMB, RGM domain family member B; IL-1Ra, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; NEGR1, neuronal growth regulator 1; Apo L1, apolipoprotein L1; ISLR2, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine rich repeat 2; VEGF sR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; S100A12, S100 calcium binding protein A12; NCAM-120, neural cell adhesion molecule 1, 120 kDa isoform; TNF-a, tumor necrosis factor alpha; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitor cytokine 1; DKK4, Dickkopf-related protein 4; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PEX5, peroxisomal biogenesis factor 5; C7, complement component 7; BMPR1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1A

Hazard ratios represent the relative hazard for a 1 SD increment in the transformed and normalized protein level

Multivariable model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension treatment, systolic blood pressure, total/HDL cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, prior myocardial infarction, and interim myocardial infarction

False discovery rate (FDR) value <0.10 was used to determine statistical significance in the discovery sample

Protein was measured on second “run” of SomaLogic platform (1.3k) only in FHS. Proteins not marked with an asterisk were measured in the full sample.

BMPR1A was not measured in HUNT

Figure 2. Multivariable-adjusted Associations of Proteins with Incident Heart Failure.

A, Proteins associated with higher risk of HF. B, Proteins associated with lower risk of HF

Abbreviations: NT-proBNP, N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide; ErbB1, epidermal growth factor receptor; MBL, mannose binding lectin; RGMC, repulsive guidance molecule C (hemojuvelin); GDF-11/8, growth/differential factor 11/8; TSP2, thrombospondin-2; NRP1, neuropilin 1; vWF, von Willebrand factor; Apo E4, apolipoprotein E (isoform E4); Apo E3, apolipoprotein E (isoform E3); RGMA, repulsive guidance molecule A; Mn SOD, superoxide dismutase [Mn], mitochondrial; Notch 1, neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 1; RGMB, RGM domain family member B; IL-1Ra, interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; NEGR1, neuronal growth regulator 1; Apo L1, apolipoprotein L1; ISLR2, immunoglobulin superfamily containing leucine rich repeat 2; VEGF sR2, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2; S100A12, S100 calcium binding protein A12; NCAM-120, neural cell adhesion molecule 1, 120 kDa isoform; TNF-a, tumor necrosis factor alpha; MIC-1, macrophage inhibitor cytokine 1; DKK4, Dickkopf-related protein 4; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PEX5, peroxisomal biogenesis factor 5; C7, complement component 7; BMPR1A, bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1A

Hazard ratios represent the relative hazard for a 1 SD increment in the transformed and normalized protein level

Multivariable model was adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, hypertension treatment, systolic blood pressure, total/HDL cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, prior myocardial infarction, and interim myocardial infarction

* Denotes proteins meeting criteria for statistical significance in meta-analysis

In secondary analyses, we compared the mean baseline values for each of the biomarkers associated with incident HF in individuals who eventually developed HFpEF (N=75) versus those that developed HFrEF (N=84) (ejection fraction was unavailable at time of HF for 15 individuals; Supplemental Table 9) and observed no statistically significant differences in biomarker concentrations across the two HF subtypes.

Replication in HUNT

In HUNT, 149 incident HF events occurred among 2497 individuals free of HF at the baseline examination cycle over a mean follow up of 6.0 years (limits 0 – 9.2 years). Consistent directionality of association was observed for the majority of the proteins in individual cohort analyses (Table 3 and Figure 2). When results from FHS and HUNT were meta-analyzed, 6 proteins were associated with incident HF after accounting for multiple testing. Modest heterogeneity in the association for some of the proteins was observed between the two cohorts. Results for one protein (bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 1A) that was associated with incident HF in FHS was not available in HUNT. Three proteins were associated with higher HF risk: N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), thrombospondin-2 (TSP2), and mannose-binding lectin (MBL); and 3 proteins were associated with lower risk: epidermal growth factor receptor (ErbB1), growth differentiation factor 11/8 (GDF-11/8), and hemojuvelin (RGMC), Table 3. Compared with models with clinical risk factors alone, the discrimination (c-statistic) of models including these proteins demonstrated modest improvements (Table 4).

Table 4.

Model discrimination for predicting incident HF with and without proteins associated with HF

| Clinical covariates | Clinical covariates + 5 proteins | Clinical covariates + 6 proteins | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-statistic | SE | C-statistic | SE | C-statistic | SE | |

| FHS | 0.859 | 0.013 | 0.872 | 0.012 | -- | -- |

| HUNT | 0.741 | 0.020 | 0.773 | 0.020 | 0.800 | 0.019 |

Clinical covariates include age, sex, body mass index, hypertension treatment, systolic blood pressure, total/HDL cholesterol, diabetes, smoking, prior myocardial infarction, and interim myocardial infarction

“5 proteins” includes the proteins measured in both batches in FHS: ErbB1, MBL, RGMC, GDF-11/8, TSP2

“6 proteins” includes the 5 proteins listed above + NT-proBNP

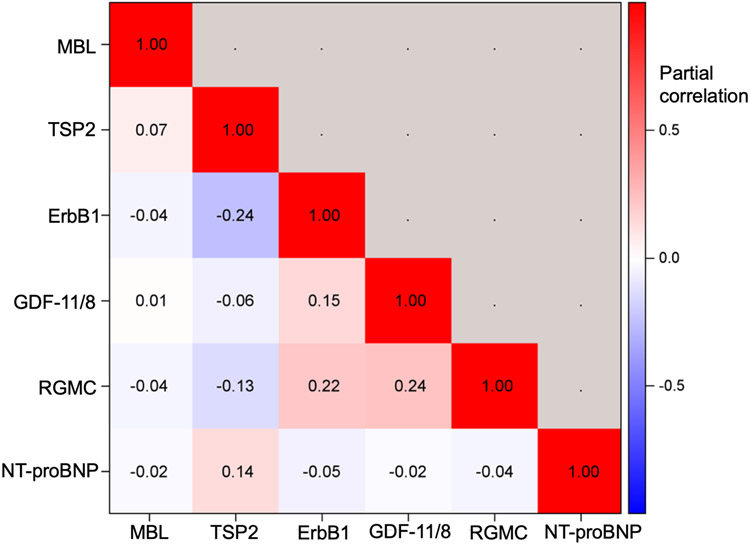

In sensitivity analyses, the 6 proteins with statistically significant associations in the meta-analyses were additionally adjusted for estimated glomerular filtration rate without any substantial changes in the protein-HF associations (Supplemental Table 10). Correlations among the circulating levels of the 6 proteins were modest (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Correlations of 6 proteins related to incident HF in meta-analysis of FHS and HUNT.

Age- and sex-adjusted partial correlations are displayed.

Corresponding mRNA abundance of relevant proteins in human heart tissue: MAGNet

Of the 6 proteins that were associated with incident HF in FHS, 5 of the 6 demonstrated expression (i.e., measurable mRNA) of the coding gene in human heart tissue (Supplemental Table 11). Transcripts for mannose binding lectin (MBL) were not observed in cardiac tissue in MAGNet. RNA levels were higher in HF hearts for TSP2 and NT-proBNP, and lower for ErbB1, consistent with their direction of associations with incident HF. RGMC levels were higher in HF hearts in MAGNet, which is directionally discordant from its association with future HF, and GDF 11 levels were not significantly different between HF and control hearts.

Associations of pQTLs

Of the 17 proteins associated with echocardiographic traits in multivariable-adjusted models, we identified 8 with pQTLs associated with echocardiographic traits in EchoGen (Supplemental Table 12, P <0.0007 for all). The majority of these pQTLs were located in trans with the coding gene for the protein, but two were located in cis (<1Mb). For the 6 proteins associated with incident HF in our meta-analyzed results, all but GDF 11 had pQTLs associated with echocardiographic traits in EchoGen (Table 5). The association of variants within the coding genes for MBL and TSP2 is particularly supportive of biological significance. RGMC was the only protein for which pQTLs also related to incident HF in CHARGE. Notably, pQTLs for NT-proBNP were not statistically significantly related to future HF.

Table 5.

Association of pQTLs for 6 proteins associated with incident HF

| Protein | Sentinel variant |

Variant position (Chr: position) |

Nearest gene (distance in kb) |

Context of variant and cognate gene (<1Mb) |

Coded/ non- coded allele |

Coded allele freq |

Effect on protein conc, β est (SE) |

P-value | Trait/ outcome |

Effect on trait, β est (SE) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT-proBNP | rs1053094 | 4:187370025 | CYP4V2 | Trans | a/t | 0.52 | 0.12 (0.03) | 5.7E-05 | LVM | −0.97 (0.28) | 0.0005 |

| ErbB1 | rs6886790 | 5:71883623 | ZNF366 (44.6) | Trans | t/c | 0.99 | 0.49 (0.12) | 6.1E-05 | LVWT | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.0004 |

| MBL | rs1343066 | 10:54346676 | MBL2 (145.2) | Cis | a/g | 0.04 | −0.68 (0.11) | 1.2E-09 | LVDD | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.0003 |

| rs10824831 | 10:54323460 | MBL2 (121.9) | Cis | a/g | 0.93 | 0.32 (0.06) | 6.1E-09 | LVM | 2.09 (0.55) | 0.0001 | |

| TSP2 | rs1485399 | 12:30140155 | TMTC1 (311.2) | Trans | t/c | 0.52 | −0.10 (0.03) | 9.6E-05 | FS | −0.16 (0.04) | 0.0004 |

| rs9717605 | 6:169394317 | THBS2 (0) | Cis | c/g | 0.26 | 0.30 (0.03) | 1.1E-24 | LAD | −0.02 (0.00) | 8.0E-06 | |

| RGMC | rs2543093 | 8:97077606 | LOC100500773 (47.9) | Trans | t/c | 0.89 | −0.22 (0.05) | 1.1E-06 | LAD | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.0003 |

| RGMC | rs6675509 | 1:167309685 | ATP1B1 (33) | Trans | a/c | 0.54 | 0.11 (0.05) | 8.1E-05 | HF | 0.09 (0.03) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: NT-proBNP, N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide; ErbB1, epidermal growth factor receptor; MBL, mannose-binding lectin; TSP2, thrombospondin-2; RGM-C, hemojuvelin

No statistically significant associations were noted between pQTLs and echocardiographic traits or HF for the proteins not listed

DISCUSSION

Principal findings

A large-scale discovery proteomic approach identified new circulating biomarkers of incident HF and cardiac remodeling in community-dwelling individuals. In analyses combining consistent associations across two separate epidemiologic cohorts, we identified six proteins to be associated with incident HF. Three proteins were associated with higher HF risk (NT-proBNP, TSP2, MBL) and 3 proteins were associated with lower risk (ErbB1, GDF 8/11, RGMC). Five of these 6 proteins also had pQTLs that were associated with either cardiac structural remodeling or incident HF in large genetic consortia. In cross-sectional analyses, a mostly separate list of 17 proteins was associated with echocardiographic traits. These findings highlight potential biological pathways and specific protein biomarkers that may prove useful for HF risk prediction and prevention.

Proteins associated with echocardiographic traits

Statistically significant associations were observed between 17 proteins and key echocardiographic traits after adjustment for clinical risk factors. Importantly, NT-proBNP – an established biomarker of echocardiographic remodeling24-26 – was positively associated with LVM, LVDD, and LAD in our sample, serving as a positive control. A large number of proteins was also related to each of the echocardiographic traits in analyses that did not account for clinical risk factors, which may suggest that traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity (and proteins associated with them) may explain a large portion of the variance in these echocardiographic measures.

RGMC was the only protein that was statistically significantly associated with both echocardiographic traits and incident HF in models adjusted for clinical risk factors. Several potential explanations exist for the apparent lack of overlap between the proteins associated with structural remodeling and those associated with future HF. Our statistical approach was designed to discover potential biomarkers with a statistical significance threshold that was conservative in regard to avoiding type I error, given the degree of correlation observed among proteins related to echocardiographic traits. Several of the proteins related to echocardiographic traits were also related to incident HF but did not meet our pre-defined statistical significance thresholds. Furthermore, predictors of HF development are not limited to those associated with cardiac traits or dysfunction.27 Indeed, mechanisms underlying cardiac structural adaptations may be insufficient to result in manifest HF without additional cardiac stressors or non-cardiac organ dysfunction. Standard criteria for diagnosing HF in epidemiologic cohorts tend to identify individuals with evidence of intravascular congestion,28 which may not be apparent until later stages of the disease process. Therefore, a larger set of proteins might be associated with abnormal cardiac structure that is evident by echocardiography but is not yet sufficient to cause overt HF symptoms.

Proteins associated with HF risk

Three proteins were associated with a higher risk of developing future HF in meta-analyses combining data from both the FHS and HUNT cohorts: NT-proBNP, TSP2, and MBL. NT-proBNP is an established biomarker for future HF development,29 and its robust association with incident HF in our study serves as a positive control. While TSP2 and MBL are not currently used for clinical HF risk assessment, both have been demonstrated to be involved in HF pathogenesis in experimental models.

TSP2 is a multimeric glycoprotein involved in cardiac extracellular matrix expansion in response to physiologic stress.30-32 Experimental TSP2 knockout models exhibit rapid cardiac dilation and rupture in response to hypertension confirming its crucial role in the adaptive response to hemodynamic stress.30 A recent study in humans found higher circulating TSP2 levels to be present in individuals with HF versus non-HF controls.11 Our findings extend this observation to two large community-based cohorts and demonstrate that higher TSP2 levels may be predictive of future HF development even from blood samples drawn more than 10 years before the diagnosis of HF.

We also observed MBL – a component of the innate immune response - to be directly related to HF risk. MBL is produced in the liver and secreted into the blood,33 consistent with our findings of undetectable RNA levels of MBL in cardiac tissues. Prior studies of the relations of circulating MBL levels and CVD have been conflicting.34 Genetically mediated lower MBL levels have been reported to confer a higher risk of coronary artery disease,35 but paradoxically are associated with lower mortality following acute myocardial infarction,36 and with protection against inflammatory cardiomyopathies such as Chagas disease.33 The role of MBL, or the underlying inflammatory pathways it represents, in HF development remains unknown.

An important strength of the present investigation is that our broad discovery proteomics approach enabled the identification of potentially cardioprotective biological pathways. Circulating levels of ErbB1 were robustly inversely related to HF risk. This finding is in line with experimental observations that ErbB1 protects against stress-induced cardiac injury,37 and a genetic knockout model develops dilated cardiomyopathy. 37 Under-expression of ErbB1 also leads to concomitant reduction in epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (ErbB2) expression in mice.37 This may have particular relevance to human heart failure as it is well known that pharmacologic inhibition of ErbB2 with trastuzumab can cause cardiotoxicity and HF.38 The role for ErbB1 monitoring or modulation for HF prevention may warrant further study.

Higher circulating levels of RGMC were also associated with lower HF risk. The RGM family of proteins are co-receptors for bone morphogenic proteins that are involved in various cellular processes.39 The two other RGM proteins found in humans (RGMA and RGMB) were also related with lower HF risk in both FHS and HUNT. While these results did not meet our threshold for statistical significance in the meta-analysis results, they are supportive of a role for the RGM family in HF protection. The association of RGMC in human disease has previously been focused on loss of function mutations resulting in hereditary juvenile hemochromatosis.39 Whether higher circulating levels are related to reduced HF risk via effects on iron metabolism or other biological functions remains to be determined.

Growth differentiation factor 8 and 11 are members of the transforming growth factor β superfamily and share similar amino acid sequences. With the generation of SOMAmer reagents used in our study, it is recognized that the DNA aptamers bind GDF 8 and 11 with similar affinities and so quantification may not be reliable.40, 41 While GDF 11 has been reported to have potential beneficial anti-aging activity in the heart,42 methodological concerns regarding its measurement have raised questions about these findings.40 GDF 8 has been demonstrated to have potential anti-hypertrophic effects in the heart, but its role remains controversial. Further investigations into the role of GDF 8 and GDF 11 in HF development is warranted.

Clinical significance

HF is a clinical condition that can be the end-result of manifold physiologic insults. Identification of novel protein biomarkers for future HF development can serve two broad goals: 1) to improve the precision of risk prediction; 2) to identify potentially modifiable biological pathways or druggable targets integral to the development of HF or related disease processes. We identified 6 protein biomarkers that were predictive of future HF development and their measurement should be further evaluated in relation to HF risk in other diverse populations. Development of focused protein arrays measuring these 6 proteins (with potential addition of other HF-associated protein biomarkers) would be a necessary next step in translating our findings to widespread clinical use. Our findings also suggest that biomarkers for which the activity is inversely related to HF risk may add additional incremental information to risk prediction. By studying community-based individuals without manifest HF, the present investigation identifies biological pathways that may be affected upstream of developing HF itself and could reveal potential insights regarding HF pathogenesis. The protective roles for the epidermal growth factor receptors and RGM family of proteins in HF pathogenesis may be of particular interest for future studies.

Limitations

Our study has several potential limitations. The SomaLogic platform used was designed to measure proteins in part with plausible relevance to cardiovascular disease and interpretation of the results should account for the fact that we only assayed a portion of the plasma proteome. Instances of cross-reactivity, nonspecific binding, and sequence variation in the aptamer binding sites have been described with the SomaScan platform, which may limit specificity and precision of protein quantification.43 SomaScan aptamers for four of the six proteins associated with incident HF in our study (TSP2, MBL, ErbB1, and NT-proBNP) have been verified using other methods for protein quantification.11, 44-46 For GDF11, there are concerns for cross-reactivity of the aptamer with GDF8 as discussed above.40, 41 In a currently unpublished meta-analysis of data from FHS and the Malmo Diet and Cancer Study, RGMC protein levels measured by the SomaScan platform associate with a genetic polymorphism within its cognate gene (P=2.7E-08). While this data supports aptamer specificity for RGMC, future studies are necessary for confirmation. Indeed, validation of all 6 proteins would be necessary prior to consideration for clinical risk prediction. Our study measured protein levels in circulating plasma. The protein levels in relevant tissues were not assessed. The echocardiograms that were performed at the FHS baseline examination cycle used for this investigation included primarily measures of cardiac structure; more precise measures of cardiac systolic and diastolic function (such as strain imaging) were not measured at this examination cycle. To control for multiple testing, we used a FDR threshold. This approach considers each protein to be statistically (and assumed to be biologically) independent and does not account for the strong correlations and interrelatedness of proteins we observed. To account for predicted statistical correlation among proteins, we used a slightly less stringent FDR threshold of <0.10 (as compared with <0.05). This approach was still likely to be conservative given the amount of correlation among proteins we observed; we may have underestimated the number of true associations (type II error), while also limiting our false positive rate (type I error). While we did not observe any differences in blood protein levels in individuals who went on to develop HFpEF vs. HFrEF, our statistical power to detect such differences was limited. For proteins reported previously to be associated with incident HF, we observed the expected directions of association for some, but not all. This may be a result of suboptimal aptamer specificity or differences between our study samples and the populations in which these biomarkers were reported. Lastly, our samples comprised mostly white individuals of European ancestry. These analyses should be validated in additional racial and ethnic groups.

CONCLUSIONS

We employed a large-scale discovery proteomic approach to identify new biomarkers of incident HF and adverse cardiac remodeling in community-dwelling individuals. We identified 17 proteins to be associated with echocardiographic traits in a community-based cohort. Six proteins were associated with future HF risk, with consistent associations across two separate epidemiologic cohorts. Our findings identify several pathways and biomarkers that warrant further investigation to determine if they may modulate or predict cardiac remodeling and HF risk.

Supplementary Material

What is new?

Using a discovery proteomics approach, 1305 circulating proteins were related to echocardiographic traits cross-sectionally and to incident heart failure prospectively in two large, community-based samples.

A total of 17 proteins were associated with echocardiographic traits and six proteins were associated with incident heart failure with consistent associations across two cohorts (Framingham Heart Study and HUNT [Nord-Trøndelag Health] study).

Several of these proteins were further supported by analyses linking genetic variants associated with their circulating levels with cardiac structural remodeling traits or incident heart failure in large genetic consortia.

What are the clinical implications?

Three proteins were associated with higher risk of heart failure and three proteins were associated with lower risk.

Our findings identify biological pathways that may be involved in both heart failure development and protection from heart failure.

Future studies are warranted to ascertain whether measuring these proteins can improve clinical heart failure risk prediction.

Acknowledgements:

Full lists of EchoGen and CHARGE-HF working group members and acknowledgements are available.21, 23

Funding sources: This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study (Contracts N01-HC-25195, HHSN268201500001I and 75N92019D00031) and by NIH grants K23-HL138260 (to Dr. Nayor), K08HL145095 (to Dr. Benson), R01HL132320 and R01HL133870 (to Dr. Gerszten). Dr. Vasan is supported by an Evans Scholar award from the Department of Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. "The Nord-Trøndelag Health (HUNT) Study is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology NTNU), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health."

Disclosures: Dr. Omland reports grants and personal fees from Roche Diagnostics, grants and personal fees from Abbott Diagnostics, and personal fees from Siemens; grants from Novartis, grants from SomaLogic, grants from Singulex, and personal fees from Bayer.

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- HF

heart failure

- FHS

Framingham Heart Study

- HUNT cohort

Nord-Trøndelag Health Study

- CV

coefficient of variation

- LVM

left ventricular mass

- LVDD

left ventricular diastolic diameter

- LAD

left atrial dimension

- AoR

aortic root diameter

- LVWT

left ventricular wall thickness

- FS

fractional shortening

- BMI

body mass index

- FDR

false discovery rate

- HR

hazard ratio

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- pQTL

protein quantitative trait loci

- NT-proBNP

N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide

- TSP2

thrombospondin-2

- MBL

mannose-binding lectin

- ErbB1

epidermal growth factor receptor

- GDF-11/8

growth differentiation factor 11/8

- RGMC

hemojuvelin

- ErbB2

epidermal growth factor receptor 2

References

- 1.Ibrahim NE and Januzzi JL Jr. Established and Emerging Roles of Biomarkers in Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2018;123:614–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Felker GM and Ahmad T. Biomarkers for the Prevention of Heart Failure: Are We There Yet? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:3255–3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Boer RA, Nayor M, deFilippi CR, Enserro D, Bhambhani V, Kizer JR, Blaha MJ, Brouwers FP, Cushman M, Lima JAC, Bahrami H, van der Harst P, Wang TJ, Gansevoort RT, Fox CS, Gaggin HK, Kop WJ, Liu K, Vasan RS, Psaty BM, Lee DS, Hillege HL, Bartz TM, Benjamin EJ, Chan C, Allison M, Gardin JM, Januzzi JL, Jr., Shah SJ, Levy D, Herrington DM, Larson MG, van Gilst WH, Gottdiener JS, Bertoni AG and Ho JE. Association of Cardiovascular Biomarkers With Incident Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow SL, Maisel AS, Anand I, Bozkurt B, de Boer RA, Felker GM, Fonarow GC, Greenberg B, Januzzi JL Jr., Kiernan MS, Liu PP, Wang TJ, Yancy CW, Zile MR, American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology Committee of the Council on Clinical C, Council on Basic Cardiovascular S, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Y, Council on C, Stroke N, Council on Cardiopulmonary CCP, Resuscitation, Council on E, Prevention, Council on Functional G, Translational B, Council on Quality of C and Outcomes R. Role of Biomarkers for the Prevention, Assessment, and Management of Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e1054–e1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemesle G, Maury F, Beseme O, Ovart L, Amouyel P, Lamblin N, de Groote P, Bauters C and Pinet F. Multimarker proteomic profiling for the prediction of cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shibayama J, Yuzyuk TN, Cox J, Makaju A, Miller M, Lichter J, Li H, Leavy JD, Franklin S and Zaitsev AV. Metabolic remodeling in moderate synchronous versus dyssynchronous pacing-induced heart failure: integrated metabolomics and proteomics study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JG and Gerszten RE. Emerging Affinity-Based Proteomic Technologies for Large-Scale Plasma Profiling in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2017;135:1651–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, Demissei BG, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, van der Harst P, Hillege HL, Lang CC, Metra M, Ng LL, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Voors AA and van der Meer P. Novel endotypes in heart failure: effects on guideline-directed medical therapy. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:4269–4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosley JD, Benson MD, Smith JG, Melander O, Ngo D, Shaffer CM, Ferguson JF, Herzig MS, McCarty CA, Chute CG, Jarvik GP, Gordon AS, Palmer MR, Crosslin DR, Larson EB, Carrell DS, Kullo IJ, Pacheco JA, Peissig PL, Brilliant MH, Kitchner TE, Linneman JG, Namjou B, Williams MS, Ritchie MD, Borthwick KM, Kiryluk K, Mentch FD, Sleiman PM, Karlson EW, Verma SS, Zhu Y, Vasan RS, Yang Q, Denny JC, Roden DM, Gerszten RE and Wang TJ. Probing the Virtual Proteome to Identify Novel Disease Biomarkers. Circulation. 2018;138:2469–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngo D, Sinha S, Shen D, Kuhn EW, Keyes MJ, Shi X, Benson MD, O’Sullivan JF, Keshishian H, Farrell LA, Fifer MA, Vasan RS, Sabatine MS, Larson MG, Carr SA, Wang TJ and Gerszten RE. Aptamer-Based Proteomic Profiling Reveals Novel Candidate Biomarkers and Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2016;134:270–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells QS, Gupta DK, Smith JG, Collins SP, Storrow AB, Ferguson J, Smith ML, Pulley JM, Collier S, Wang X, Roden DM, Gerszten RE and Wang TJ. Accelerating Biomarker Discovery Through Electronic Health Records, Automated Biobanking, and Proteomics. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2195–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganz P, Heidecker B, Hveem K, Jonasson C, Kato S, Segal MR, Sterling DG and Williams SA. Development and Validation of a Protein-Based Risk Score for Cardiovascular Outcomes Among Patients With Stable Coronary Heart Disease. JAMA. 2016;315:2532–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacob J, Ngo D, Finkel N, Pitts R, Gleim S, Benson MD, Keyes MJ, Farrell LA, Morgan T, Jennings LL and Gerszten RE. Application of Large-Scale Aptamer-Based Proteomic Profiling to Planned Myocardial Infarctions. Circulation. 2018;137:1270–1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams SA, Murthy AC, DeLisle RK, Hyde C, Malarstig A, Ostroff R, Weiss SJ, Segal MR and Ganz P. Improving Assessment of Drug Safety Through Proteomics: Early Detection and Mechanistic Characterization of the Unforeseen Harmful Effects of Torcetrapib. Circulation. 2018;137:999–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ and Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyngbakken MN, Skranes JB, de Lemos JA, Nygard S, Dalen H, Hveem K, Rosjo H and Omland T. Impact of Smoking on Circulating Cardiac Troponin I Concentrations and Cardiovascular Events in the General Population: The HUNT Study (Nord-Trondelag Health Study). Circulation. 2016;134:1962–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson MD, Yang Q, Ngo D, Zhu Y, Shen D, Farrell LA, Sinha S, Keyes MJ, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Smith JG, Wang TJ and Gerszten RE. Genetic Architecture of the Cardiovascular Risk Proteome. Circulation. 2018;137:1158–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blom G Statistical estimates and transformed beta-variables. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Das A, Morley M, Moravec CS, Tang WH, Hakonarson H, Consortium MA, Margulies KB, Cappola TP, Jensen S and Hannenhalli S. Bayesian integration of genetics and epigenetics detects causal regulatory SNPs underlying expression variability. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wild PS, Felix JF, Schillert A, Teumer A, Chen MH, Leening MJG, Volker U, Grossmann V, Brody JA, Irvin MR, Shah SJ, Pramana S, Lieb W, Schmidt R, Stanton AV, Malzahn D, Smith AV, Sundstrom J, Minelli C, Ruggiero D, Lyytikainen LP, Tiller D, Smith JG, Monnereau C, Di Tullio MR, Musani SK, Morrison AC, Pers TH, Morley M, Kleber ME, Aragam J, Benjamin EJ, Bis JC, Bisping E, Broeckel U, Cheng S, Deckers JW, Del Greco MF, Edelmann F, Fornage M, Franke L, Friedrich N, Harris TB, Hofer E, Hofman A, Huang J, Hughes AD, Kahonen M, Investigators K, Kruppa J, Lackner KJ, Lannfelt L, Laskowski R, Launer LJ, Leosdottir M, Lin H, Lindgren CM, Loley C, MacRae CA, Mascalzoni D, Mayet J, Medenwald D, Morris AP, Muller C, Muller-Nurasyid M, Nappo S, Nilsson PM, Nuding S, Nutile T, Peters A, Pfeufer A, Pietzner D, Pramstaller PP, Raitakari OT, Rice KM, Rivadeneira F, Rotter JI, Ruohonen ST, Sacco RL, Samdarshi TE, Schmidt H, Sharp ASP, Shields DC, Sorice R, Sotoodehnia N, Stricker BH, Surendran P, Thom S, Toglhofer AM, Uitterlinden AG, Wachter R, Volzke H, Ziegler A, Munzel T, Marz W, Cappola TP, Hirschhorn JN, Mitchell GF, Smith NL, Fox ER, Dueker ND, Jaddoe VWV, Melander O, Russ M, Lehtimaki T, Ciullo M, Hicks AA, Lind L, Gudnason V, Pieske B, Barron AJ, Zweiker R, Schunkert H, Ingelsson E, Liu K, Arnett DK, Psaty BM, Blankenberg S, Larson MG, Felix SB, Franco OH, Zeller T, Vasan RS and Dorr M. Large-scale genome-wide analysis identifies genetic variants associated with cardiac structure and function. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1798–1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasan RS, Glazer NL, Felix JF, Lieb W, Wild PS, Felix SB, Watzinger N, Larson MG, Smith NL, Dehghan A, Grosshennig A, Schillert A, Teumer A, Schmidt R, Kathiresan S, Lumley T, Aulchenko YS, Konig IR, Zeller T, Homuth G, Struchalin M, Aragam J, Bis JC, Rivadeneira F, Erdmann J, Schnabel RB, Dorr M, Zweiker R, Lind L, Rodeheffer RJ, Greiser KH, Levy D, Haritunians T, Deckers JW, Stritzke J, Lackner KJ, Volker U, Ingelsson E, Kullo I, Haerting J, O’Donnell CJ, Heckbert SR, Stricker BH, Ziegler A, Reffelmann T, Redfield MM, Werdan K, Mitchell GF, Rice K, Arnett DK, Hofman A, Gottdiener JS, Uitterlinden AG, Meitinger T, Blettner M, Friedrich N, Wang TJ, Psaty BM, van Duijn CM, Wichmann HE, Munzel TF, Kroemer HK, Benjamin EJ, Rotter JI, Witteman JC, Schunkert H, Schmidt H, Volzke H and Blankenberg S. Genetic variants associated with cardiac structure and function: a meta-analysis and replication of genome-wide association data. Jama. 2009;302:168–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith NL, Felix JF, Morrison AC, Demissie S, Glazer NL, Loehr LR, Cupples LA, Dehghan A, Lumley T, Rosamond WD, Lieb W, Rivadeneira F, Bis JC, Folsom AR, Benjamin E, Aulchenko YS, Haritunians T, Couper D, Murabito J, Wang YA, Stricker BH, Gottdiener JS, Chang PP, Wang TJ, Rice KM, Hofman A, Heckbert SR, Fox ER, O’Donnell CJ, Uitterlinden AG, Rotter JI, Willerson JT, Levy D, van Duijn CM, Psaty BM, Witteman JC, Boerwinkle E and Vasan RS. Association of genome-wide variation with the risk of incident heart failure in adults of European and African ancestry: a prospective meta-analysis from the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology (CHARGE) consortium. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:256–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velagaleti RS, Gona P, Levy D, Aragam J, Larson MG, Tofler GH, Lieb W, Wang TJ, Benjamin EJ and Vasan RS. Relations of biomarkers representing distinct biological pathways to left ventricular geometry. Circulation. 2008;118:2252–8, 5p following 2258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Larson MG, Leip EP, Wang TJ, Wilson PWF and Levy D. Natriuretic Peptides for Community Screening for Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Systolic Dysfunction: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 2002;288:1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groenning BA, Nilsson JC, Sondergaard L, Pedersen F, Trawinski J, Baumann M, Larsson HBW and Hildebrandt PR. Detection of left ventricular enlargement and impaired systolic function with plasma N-terminal pro brain natriuretic peptide concentrations. American Heart Journal. 2002;143:923–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam CS, Lyass A, Kraigher-Krainer E, Massaro JM, Lee DS, Ho JE, Levy D, Redfield MM, Pieske BM, Benjamin EJ and Vasan RS. Cardiac dysfunction and noncardiac dysfunction as precursors of heart failure with reduced and preserved ejection fraction in the community. Circulation. 2011;124:24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roger VL. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013;113:646–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, Leip EJ, O’mland T, Wolf PA and Vasan RS. Plasma Natriuretic Peptide Levels and the Risk of Cardiovascular Events and Death. N Engl J Med. 2009;350:655–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schroen B, Heymans S, Sharma U, Blankesteijn WM, Pokharel S, Cleutjens JP, Porter JG, Evelo CT, Duisters R, van Leeuwen RE, Janssen BJ, Debets JJ, Smits JF, Daemen MJ, Crijns HJ, Bornstein P and Pinto YM. Thrombospondin-2 is essential for myocardial matrix integrity: increased expression identifies failure-prone cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004;95:515–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chistiakov DA, Melnichenko AA, Myasoedova VA, Grechko AV and Orekhov AN. Thrombospondins: A Role in Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schellings MW, van Almen GC, Sage EH and Heymans S. Thrombospondins in the heart: potential functions in cardiac remodeling. J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:201–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisen DP and Minchinton RM. Impact of mannose-binding lectin on susceptibility to infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1496–1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heitzeneder S, Seidel M, Forster-Waldl E and Heitger A. Mannan-binding lectin deficiency - Good news, bad news, doesn’t matter? Clin Immunol. 2012;143:22–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Best LG, Davidson M, North KE, MacCluer JW, Zhang Y, Lee ET, Howard BV, DeCroo S and Ferrell RE. Prospective analysis of mannose-binding lectin genotypes and coronary artery disease in American Indians: the Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;109:471–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trendelenburg M, Theroux P, Stebbins A, Granger C, Armstrong P and Pfisterer M. Influence of functional deficiency of complement mannose-binding lectin on outcome of patients with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:1181–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pareja M, Sanchez O, Lorita J, Soley M and Ramirez I. Activated Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (ErbB1) Protects the Heart Against Stress-Induced Injury in Mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cote GM, Sawyer DB and Chabner BA. ERBB2 inhibition and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corradini E, Babitt JL and Lin HY. The RGM/DRAGON family of BMP co-receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:389–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schafer MJ, Atkinson EJ, Vanderboom PM, Kotajarvi B, White TA, Moore MM, Bruce CJ, Greason KL, Suri RM, Khosla S, Miller JD, Bergen HR 3rd and LeBrasseur NK. Quantification of GDF11 and Myostatin in Human Aging and Cardiovascular Disease. Cell Metab. 2016;23:1207–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Short Technical Note on SOMAmer reagent. Somalogic. 2019. https://12tksl28b87d3fw47i3ndu3e-wpengine.netdnassl.com/wpcontent/uploads/2019/07/Short-Technical-Note-SOMAmer-specificity.pdf

- 42.Loffredo FS, Steinhauser ML, Jay SM, Gannon J, Pancoast JR, Yalamanchi P, Sinha M, Dall’Osso C, Khong D, Shadrach JL, Miller CM, Singer BS, Stewart A, Psychogios N, Gerszten RE, Hartigan AJ, Kim MJ, Serwold T, Wagers AJ and Lee RT. Growth differentiation factor 11 is a circulating factor that reverses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 2013;153:828–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joshi A and Mayr M. In Aptamers They Trust: The Caveats of the SOMAscan Biomarker Discovery Platform from SomaLogic. Circulation. 2018;138:2482–2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Emilsson V, Ilkov M, Lamb JR, Finkel N, Gudmundsson EF, Pitts R, Hoover H, Gudmundsdottir V, Horman SR, Aspelund T, Shu L, Trifonov V, Sigurdsson S, Manolescu A, Zhu J, Olafsson Ö, Jakobsdottir J, Lesley SA, To J, Zhang J, Harris TB, Launer LJ, Zhang B, Eiriksdottir G, Yang X, Orth AP, Jennings LL and Gudnason V. Co-regulatory networks of human serum proteins link genetics to disease. Science (New York, NY). 2018;361:769–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ngo D, Sinha S, Shen D, Kuhn EW, Keyes MJ, Shi X, Benson MD, O’Sullivan JF, Keshishian H, Farrell LA, Fifer MA, Vasan RS, Sabatine MS, Larson MG, Carr SA, Wang TJ and Gerszten RE. Aptamer-Based Proteomic Profiling Reveals Novel Candidate Biomarkers and Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation. 2016;134:270–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, Burgess S, Jiang T, Paige E, Surendran P, Oliver-Williams C, Kamat MA, Prins BP, Wilcox SK, Zimmerman ES, Chi A, Bansal N, Spain SL, Wood AM, Morrell NW, Bradley JR, Janjic N, Roberts DJ, Ouwehand WH, Todd JA, Soranzo N, Suhre K, Paul DS, Fox CS, Plenge RM, Danesh J, Runz H and Butterworth AS. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature. 2018;558:73–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.