Abstract

Patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are at an increased risk of developing intestinal neoplasia—particularly colorectal neoplasia, including dysplasia and colorectal cancer (CRC)—as a primary consequence of chronic inflammation. While the current incidence of CRC in IBD is lower compared with prior decades, due, in large part, to more effective therapies and improved colonoscopic technologies, CRC still accounts for a significant proportion of IBD-related deaths. The focus of this review is on the pathogenesis; epidemiology, including disease- and patient-related risk factors; diagnosis; surveillance; and management of IBD-associated neoplasia.

Keywords: cancer prevention, colonic neoplasms, Crohn’s disease, diagnostic techniques, digestive system, early diagnosis, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract driven by inappropriate immune responses to an altered gut microbiome in genetically susceptible individuals.1 IBD affects at least 0.4% of Europeans and North Americans, with a rising prevalence worldwide including in areas such as Asian-Pacific and developing countries, where IBD was not described previously.2–4 It is well recognized that individuals with IBD are at increased risk of developing intestinal neoplasia—particularly colorectal neoplasia (CRN), colorectal dysplasia and colorectal cancer (CRC)—as a primary consequence of chronic colonic inflammation compounded by intermittent episodes of acute or subacute inflammation as part of the natural disease course.5–7 Presently, the incidence of CRC in IBD is lower compared with prior decades due, among other factors, to more effective and safer therapies to control inflammation and improved colonoscopic technologies. Nevertheless, CRC still accounts for a significant proportion of IBD-related deaths.8,9

Despite considerable progress in our understanding of IBD pathogenesis and management, intestinal neoplasia is still a common complication of disease. Moreover, sporadic CRC and inflammation-associated cancer may still develop in patients with IBD. The focus of this review is on the pathogenesis, epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of intestinal neoplasia, namely colorectal dysplasia and CRC, attributed to chronic intestinal inflammation in IBD.

Pathogenesis

In IBD, recurrent mucosal inflammation is the primary trigger for intestinal neoplasia. Current data support overlap between the carcinogenic pathways and molecular mechanisms of the dysplasia to carcinoma sequence implicated in sporadic CRN and those of IBD-associated neoplasia, albeit with some nuances. For example, mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene, aneuploidy, DNA methylation, microsatellite instability (MSI), activation of the oncogene k-ras, activation of Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), mutation in tumor suppressor genes deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC)/deleted in pancreatic cancer-4 (DPC4), and eventual loss of tumor protein 53 (p53) function may be observed in either sporadic or IBD-associated CRN.10 However, intestinal inflammation—the sine que non of IBD—alters the timing, frequency, and sequence of these genomic changes, yielding a process of carcinogenesis that is faster and more often multifocal.6,11 IBD-associated CRC less often have APC and k-ras mutations and more often have p53, isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1), and MYC mutations compared with sporadic tumors.12–16 Moreover, chronic colonic inflammation creates a “field effect,” with any inflamed segment at risk for neoplastic transformation.17,18 Several human and animal studies have demonstrated that, in addition to reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, proinflammatory cytokines produced during chronic inflammation can induce genetic and epigenetic changes through a variety of pathways, including point mutations, deletions, duplications, recombinations, and methylation of various tumor-related genes through various mechanisms.19 Indeed, methylation in gene promoters, such as those of ITGA4 and TFPI2, may be suitable risk biomarkers for inflammation-associated CRC.20 These molecular and epigenetic events induced by chronic inflammation alter pathways involved in normal cellular function and stimulate carcinogenesis directly. Further studies are required to identify feasible and clinically relevant biomarkers to identify patients at risk for CRN due to chronic inflammation.

Differing from sporadic CRC, in which the dysplastic precursor is the adenomatous polyp, dysplasia in IBD can be localized, diffuse, or multifocal.6,21 Small bowel cancer (SBC), although lacking in data overall, is often found in inflamed ileal segments with previous or synchronous ileal dysplasia, suggesting that inflammation-associated SBC may evolve similarly to CRC, although the genetic and molecular signatures are less defined.22

Epidemiology

Many referral centers and population-based studies have aimed to quantify the relative risk of CRC in patients with IBD compared with the general population. However, as multiple factors influence the risk of dysplasia and CRC, such as disease duration, severity, and extent, heterogeneity in study design and population might lead to heterogeneity in risk estimates.23 Biases including selection or detection bias must also be considered since asymptomatic individuals in the general population at otherwise average risk for CRC would reasonably undergo colonoscopy for CRC screening purposes only at the age of 45–50 years. While the incidence of CRC in the IBD population appears to be decreasing, most notably in European cohorts,24,25 based on several meta-analyses of population-based studies published over the past 10–15 years, the pooled risk for incident CRC remains elevated by nearly twofold for patients with IBD relative to general population controls.24,26–28 With the exception of one United States (US)-based study from Olmsted County, Minnesota,29 which reported no increased risk of CRC-related mortality in patients with IBD, most population-based studies have demonstrated a 1.2- to 2-fold higher risk of CRC-related mortality among patients with IBD, even in the modern era.25,30

Disease-related risk factors for CRN in IBD

A wide body of literature consisting of studies from both population- and referral center-based studies informs our understanding of the risk factors for IBD-associated CRN; however, risk estimates from older studies must be interpreted in context since these are from a time prior to high-definition white light endoscopy (HD-WLE) and other technologies for enhanced neoplasia detection, and also prior to the introduction of therapies to better control inflammatory burden in IBD.17,31–33 Generally speaking, though, disease-specific risk factors include disease duration, extent, and degree of inflammation (Table 1). Duration of colonic disease has long been recognized as an important factor predicting CRC risk in IBD.34,35 A large meta-analysis from 2001, which included studies from 1966 to 1999, initially reported a cumulative CRC incidence of nearly 8% by 20 years and 18% by 30 years of disease among UC patients.36 A more recent meta-analysis of population-based and referral center studies reported a 2.6% (95% CI 0.8–4.7) and 6.6% (95% CI 1.3–13.8) cumulative risk of CRC at 10–20 years and over 20 years of IBD duration, respectively, with a 21% cumulative risk of CRC among patients with extensive disease of over 20 years duration.24 Similarly, the cumulative incidence of CRC in a prospective surveillance cohort of patients with extensive UC from St. Mark’s Hospital in the United Kingdom (UK) was reported to be 2.5% at 20 years, 7.6% at 30 years, and 10.8% at 40 years of disease.5 A Dutch study of IBD patients found that, after adjusting for age, sex, colonic disease extent, presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), and presence of pseudopolyps, patients with more than 20 years of disease had a risk ratio (RR) of 4.42 [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.07–6.36] for the development of CRC compared with patients with less than 10 years of disease.37 Despite these consistent data, most of these studies evaluated historical cohorts prior to (a) the widespread utilization of more effective therapies to control inflammation, namely biological and small molecule therapies; (b) robust data supporting the benefit of treat-to-target paradigm of mucosal healing, coupled with availability of noninvasive surrogate markers of mucosal and histologic healing; (c) data supporting the benefit of colonic surveillance programs in IBD38; and (d) enhanced technology, such as HD-WLE, for dysplasia detection. As such, these risk assessments may overestimate the impact of disease duration on CRC risk in current IBD cohorts and practice, which is problematic since, in the absence of concomitant PSC or high-risk family history, disease duration, as opposed to other determinants such as cumulative inflammatory burden, dictates when to initiate colonoscopic CRN surveillance in IBD according to current guideline recommendations.

Table 1.

Clinical risk factors for IBD-associated colorectal neoplasia.

| Patient-specific factors | Disease-specific factors | Inflammatory complications |

|---|---|---|

| PSC | Age of IBD onset | Stricture (+/–) |

| Personal history of CRN | Disease duration | Shortened tubular colon |

| Family history of CRC in first-degree relative | Disease extent | Pseudopolyps* |

| Smoking | Cumulative inflammatory burden | |

| Male sex (+/–) | Disease severity (endoscopic and histologic) |

Recent multicenter retrospective cohort studies which control for inflammation and other relevant confounders do not support an independent association of pseudopolyps with advanced CRN (see text).

CRC, colorectal cancer; CRN, colorectal neoplasia; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Colonic disease extent is also well recognized as an important factor predicting CRC risk in IBD. However, extent of colitis may change over time, and the majority of studies measured extent at a single time point, such as at diagnosis or study entry. Individuals with IBD limited to the rectum (proctitis) do not have a higher risk of CRC compared with the general population, and, thus, unless there is proximal extension of disease, do not warrant colonoscopic surveillance for CRN.28 By contrast, those with any history of extensive colitis have a considerably higher risk of CRC relative to the general population.24,39 A frequently cited study from Sweden on patients diagnosed with UC between 1922 and 1983 yielded a RR of 14.8 (95% CI 11.4–18.9) for pancolitis compared with a RR 2.8 (95% CI 1.6–4.4) in left-sided colitis, and no increased risk with proctitis.40

Severity of inflammation is an established risk factor for CRC in IBD. However, interpretation of the existing data is complicated by heterogeneity across studies, particularly with respect to the diagnostic modality for assessing inflammation severity and capturing its change over time. Limited studies have shown that severity by endoscopic (RR 5.1, 95% CI 2.7–11.1) or histologic (RR 3.0, 95% CI 1.4–6.3) disease directly impacts risk of progression to CRC.17,41 Likely, the more predictive determinant is cumulative inflammatory burden—that is, severity of inflammation over time—which is not adequately captured in most studies. Structural “surrogate” markers, though, of cumulative inflammatory burden might include post-inflammatory polyposis, strictures, tubular colon, and foreshortened colon (often the result of intestinal surgery), as discussed further below.18,42–46 In a single-center cohort study of 987 patients followed over 13 years, cumulative inflammatory burden, defined as the sum of average score between each pair of surveillance episodes multiplied by the surveillance interval in years, was significantly associated with risk of CRN development. For every 10-unit increase in cumulative inflammatory burden, or for every 10, 5, or 3 years of continuous mild, moderate, or severe inflammation, respectively, there was a 2.1-fold (95% CI 1.4–3.0) higher risk of CRN.47 Importantly, severity of inflammation based on recent colonoscopy alone was not significant [hazard ratio (HR) 0.9 per-1-unit increase in severity, 95% CI 0.7–1.2], whereas the mean severity score calculated from all colonoscopies performed in preceding 5 years was significantly associated with the risk of CRN (HR 2.2 per-1-unit increase; 95% CI 1.6–3.1). This is highly relevant, since most current guidelines base recommended surveillance intervals based on the most recent colonoscopic findings.

Regarding structural lesions as surrogates for inflammation severity and course over time, previous small studies suggested that the cumulative risk of dysplasia or cancer associated with strictures ranged from 0% to 86%, with up to 40% of strictures themselves harboring cancer.18,45,48,49 More recently, in a study of 293 patients with colonic strictures undergoing surgery for non-neoplastic diagnosis, nearly 4% of strictures harbored preoperatively undiagnosed cancer. In a study of patients with IBD diagnosed with colonic strictures without known preoperative neoplasia who underwent surgical resection of the stricture, among patients with UC or IBD-unclassified (IBD-U; n = 45), 2%, 2%, and 5% were found to have low-grade dysplasia (LGD), high-grade dysplasia (HGD), and CRC, respectively, whereas, among patients with CD (n = 245), 1%, 0.4%, and 0.8% were found to have LGD, HGD, and CRC, respectively.48 Based on these data, the risk of malignant transformation from dysplasia to CRC in strictures is low, suggesting that many may be managed safely with surveillance.50 Recent data from large cohort studies controlling for inflammatory burden have demonstrated that post-inflammatory polyps, or “pseudopolyps,” are not an independent risk factor for CRC, and more likely reflect cumulative inflammatory burden.51 Studies have reported a low risk of malignant transformation of pseudopolyps, supporting the practice of not removing pseudopolyps unless there is diagnostic uncertainty or features concerning for malignancy.51,52 However, if quality colonoscopic surveillance is unable to be performed due to severe pseudopolyposis interfering with visualization, colectomy should be seriously considered.42

Patient-related risk factors for CRN in IBD

Patient-related risk factors for CRC include concomitant PSC, prior history of CRN, family history of CRC in a first-degree relative particularly if diagnosed before age 50, smoking, and age of IBD onset (Table 1).42 PSC is major risk factor for CRN, as well as hepatobiliary cancers such as cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer. A meta-analysis of 11 studies in UC found an odds ratio (OR) of 4.09 (95% CI 2.89–5.76) for CRC in patients with PSC compared with those without PSC.53 In a population-based study from Denmark, comprising 32,911 patients with UC and 14,463 patients with CD, adjusting for age, sex, and calendar time, the presence of PSC was a strong risk factor for CRC in UC (RR 9.13, 95% CI 4.52–18.5) but not in CD (RR 2.90, 95% CI 0.40–20.9), or more specifically in Crohn’s colitis (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.43–1.49).32 There is also differential risk of progression of dysplasia in patients with colonic IBD with versus without PSC. A recent multicenter cohort study reported a risk of progression of LGD to advanced CRN (i.e. HGD or CRC) that was nearly threefold higher in patients with confirmed colonic IBD and concomitant PSC (8.4 per 100 patient-years) versus no PSC (2.0 per 100 patient-years; p = 0.01).54 A separate multicenter study of 1911 patients with colonic IBD (293 with PSC and 1618 without PSC) similarly reported that the rate of advanced CRN following a LGD diagnosis was 2.8 times higher in patients with IBD and concomitant PSC compared with those without PSC.41 In addition to the elevated risk of CRN, providers who care for patients with IBD and concomitant PSC must also be aware of the elevated risk of hepatobiliary cancers, and ensure appropriate screening/surveillance is similarly achieved. It is estimated that the risk of developing cholangiocarcinoma in patients with PSC is 0.5–1.5% per year, with a lifetime prevalence of 5–20%.55,56 In addition to cholangiocarcinoma, an increased frequency of gallbladder carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma is also observed in patients with PSC.57

Family history of CRC in a first-degree relative with CRC younger than 50 years of age is also a strong risk factor, and, accordingly, is recommended by most gastroenterology (GI) societies as one factor for risk stratification to determine CRN surveillance initiation in the proband. Based on a population-based cohort study of 19,876 individuals with IBD born between 1941 and 1995, among patients with IBD colitis, having a first-degree relative with CRC diagnosed younger or equal to 50 years was associated with a 9.2-fold (95% CI 3.7–23.0) higher risk of CRC.58 Having a first-degree relative who was diagnosed with CRC after age 50 is still associated with a lower, but persistently elevated, risk, demonstrating an associated 2.5-fold (95% CI 1.4–4.4) increased risk.42,58

While ample data confirm a high risk of advanced CRN following a diagnosis of LGD,59–61 the clinical significance and course of indefinite dysplasia (IND) is less well defined. Recently, a single-center retrospective cohort of 492 patients with colonic IBD for ⩾8 years, of whom 53 (11%) were diagnosed with IND without prior or synchronous LGD, demonstrated that IND alone was associated with a significantly higher risk of advanced CRN (adjusted HR 6.85, 95% CI 1.78–26.4)—that is HGD or CRC—or CRN (adjusted HR 3.25; 95% CI 1.50–7.05), defined as LGD, HGD, or CRC, compared with patients without any history of dysplasia.62 In this study, IND was confirmed by an expert GI pathologist and the authors adjusted for relevant confounders including histologic inflammation score. These data emphasize the importance of confirming histologic diagnoses of IND as well as ensuring adequate control of inflammation and continued surveillance.

IBD-associated CRC generally occurs at a younger age than sporadic CRC.37 Age and age of IBD-onset have been shown to be risk factors for CRC in IBD, with younger age of IBD onset generally associated with an increased risk that has been attributed to more aggressive disease phenotype and perhaps greater cumulative inflammatory burden. A meta-analysis of five population-based studies demonstrated a pooled standardized incidence ratio (SIR) for CRC of 8.2 (95% CI 1.8–14.6, I2 82%) for age at IBD diagnosis younger than 30 years and a pooled SIR for CRC of 1.8 (0.9–2.7, I2 81%) for age at IBD diagnosis older than 30 years.24 A population-based study from Denmark demonstrated that, among patients diagnosed with UC before age 19, the SIR was 43.8 (95% CI 27.2–70.7), among those diagnosed in between 20 and 39 years, the SIR was 2.65 (95% CI 1.97–3.56), and among those diagnosed in between 60 and 79 years, the SIR was 0.76 (95% CI 0.62–0.92).32 A population-based study from Sweden found a higher cumulative incidence of CRC in patients diagnosed with extensive colitis before the age of 14 years compared with other age groups.40 More recently, in a population-based cohort study of 96,447 patients with UC in Denmark (n = 32,919) and Sweden (n = 63,528), the HR of incident CRC was particularly high for childhood-onset UC (HR 37.0, 95% CI 25.1–54.4), whereas patients with elderly onset UC had no increased risk of CRC (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.88–1.08).63 Similarly, in a population-based cohort study of 47,035 patients with CD in Denmark (n = 13,056) and Sweden (n = 33,979), the risk of CRC was highest in children (HR 5.90, 95% CI 3.43–10.2), reflecting cumulative inflammatory burden.64

Males with IBD might have a higher relative risk of CRC compared with females. A meta-analysis of four population-based studies reported a pooled SIR for CRC of 2.6 (95% CI 2.2–3.0) and 1.9 (95% CI 1.5–2.3) in males and females with UC, respectively,65–68 although this was not statistically significant.28 More recently, a meta-analysis of three population-based studies in IBD (n = 9980 patients) reported a pooled SIR for CRC of 1.9 (95% CI 0.3–3.0) in males and 1.4 (95% CI 0.8–2.1) in females,65,68,69 while pooled SIRs based on data from three referral centers (n = 2090 patients) were 6.7 (95% CI 0.3–13.1) and 6.9 (95% CI 2.7–11.7) in males and females with IBD, respectively.24,70–72

Diagnosis and surveillance

No randomized controlled trials have compared the efficacy of colonoscopic surveillance with no colonoscopic surveillance in reducing incident CRC and related mortality in patients with IBD. As such, the endorsement for endoscopic surveillance programs by major GI and cancer societies is based on indirect evidence of benefit with respect to patient important outcomes.34,73–78

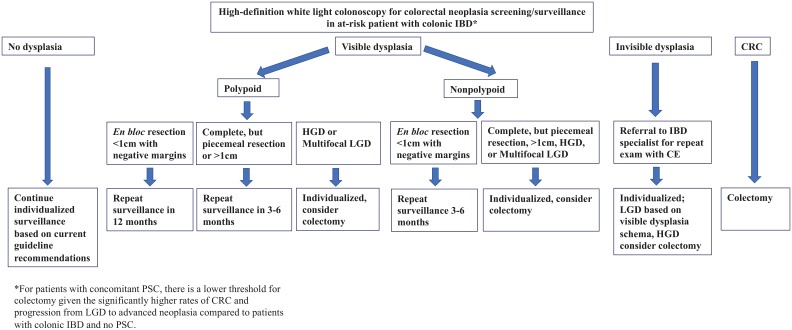

Among patients with colonic IBD who are diagnosed with PSC, colonoscopy should be performed at the time of PSC diagnosis with continued annual surveillance thereafter, unless other factors, such as LGD in the absence of colectomy planning, dictate shorter interval surveillance. Otherwise, among patients without concomitant PSC, the interval for surveillance varies by society, with some recommending specific intervals based on risk stratification (high-, intermediate-, low-risk according to patient- and disease-related clinical characteristics),52,79 while others suggest a comparatively non-stratified approach. Generally, US guidelines recommend that CRN surveillance commences 8–10 years after diagnosis among patients with colonic involvement, and continues at an interval of 1–3 years based on patient- and disease-related factors (Figure 1). Among patients with a first-degree relative with CRC, the initial exam should occur 10 years prior to age of CRC in the first-degree relative or after 8 years of IBD, whichever occurs first. Patients with isolated IBD proctitis do not require regular surveillance after the initial exam, unless there is confirmed proximal disease extension.

Figure 1.

Schema for the management of patients with colonic IBD undergoing surveillance for CRN.

CE, chromoendoscopy; CRN, colorectal neoplasia; CRC, colorectal cancer; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; LGD, low-grade dysplasia.

Quality metrics for colonoscopic surveillance in IBD generally reflect CRC screening and surveillance recommendations in the general population, albeit with some additional considerations including the use of image-enhancing techniques, such as chromoendoscopy.34,52,78–81 It is recommended that surveillance examinations be performed by an experienced gastroenterologist in IBD when disease is in remission and with adequate bowel preparation. While active disease should not preclude a surveillance exam, the extent and severity of disease activity should be noted. Even with active disease, the identification of LGD, HGD, and CRC is still reliable with interobserver agreement. In quiescent disease, a large field of pseudopolyps, scars, or impassable strictures that may compromise surveillance should prompt discussion of colectomy. Despite guidelines and quality metrics, widespread adherence to recommended surveillance techniques remains low.82–85

Prior to HD-WLE, standard of care for surveillance using standard definition white light endoscopy (SD-WLE) included four quadrant nontargeted random biopsies every 10 cm from the cecum to the rectum (minimum 32 biopsies), placed in separate jars, with the goal of detecting subtle or “invisible” dysplasia. In addition to targeted biopsies of any visible lesions or concerning mucosal areas, obtaining biopsies from the surrounding normal-appearing mucosa and placing this in separately labeled jars was also recommended as a way to evaluate for invisible dysplasia or inflammation. However, SD-WLE is no longer acceptable for surveillance,80,86 and has been replaced with newer, better, technology (HD-WLE) and other image-enhancing techniques such as chromoendoscopy (CE). These advances have substantially improved dysplasia detection and have brought into question whether “invisible” dysplasia is a true entity.87,88 Application of dye CE during colonoscopy with indigo carmine or methylene blue might improve visualization of subtle lesions by highlighting the distinction between inflamed mucosa and precancerous dysplastic lesions, assuming of course there is adequate mucosal visualization—that is, adequate bowel preparation, minimal pseudopolyps, and endoscopically quiescent disease. A meta-analysis of six studies including 1358 patients with IBD undergoing surveillance with CE (n = 670) or HD-WLE (n = 688) found that more dysplasia was identified on CE compared with HD-WLE (19% versus 9%, p = 0.08).89 Recently, a randomized controlled trial comparing HD-WLE with random biopsies (n = 102) with CE with targeted biopsies (n = 108), showed no difference in dysplasia detection.90 Similarly, other image-enhancing adjuncts to complement HD-WLE—such as virtual chromoendoscopy (VCE) and narrow-band imaging, both of which provide mucosal contrast enhancement without dye—unfortunately have also not demonstrated higher yield of dysplasia detection.50,80,91,92 In fact, a recent randomized controlled trial comparing VC, CE, and HD-WLE found that HD-WLE and VC were non-inferior to CE, with the authors concluding that HD-WLE was sufficient for the detection of dysplasia.93

Although CE is endorsed by the Surveillance for Colorectal Endoscopic Neoplasia Detection and Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: International Consensus (SCENIC) recommendations,80 the role of CE and random biopsies in the era of HD-WLE is controversial as the vast majority of neoplasia is accepted to be visible, not to mention that CE adds procedural time and might be cumbersome.86,88,90,94–96 A recent single-center study reported that, among 302 polypoid lesions biopsied or resected from 131 patients with IBD in whom lesion-adjacent biopsies were obtained, the yield for invisible dysplasia was 0%.97 Current data do, however, support random biopsies with CE for those at high risk of CRC, including patients with PSC, a personal history of dysplasia, or a tubular-appearing colon suggestive of high cumulative inflammatory burden.88 Currently, questions remain regarding which surveillance technique is superior for the group of patients with IBD and colonic involvement but no other risk factors for CRC: HD-WLE with random biopsies, HD-WLE with CE and targeted biopsies, or HD-WLE with targeted biopsies.

Dysplasia types and categories

The management of IBD-associated dysplasia hinges on consistent definitions and appropriate endoscopic characterization of lesions. These descriptors are critical for determining resectability, prognosis, and future surveillance. Recently, imprecise terminologies such as dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM), adenoma-associated lesion or mass (ALM), flat and raised dysplasia, were replaced by a modified Paris classification,98 which has been classically applied to dysplastic lesions diagnosed in individuals without IBD, in an effort to describe dysplastic lesions in individuals with IBD more appropriately and consistently.80 The SCENIC consensus statement recommended broad categorization of dysplasia as “visible”, defined as a dysplastic lesion seen on endoscopy, and “invisible”, defined as dysplasia diagnosed on histopathology from a nontargeted biopsy in the absence of a discrete lesion. The modified classification also included polypoid and nonpolypoid lesions under the broader category of “visible,” and was further modified to include descriptors for visible dysplasia, including the presence of ulceration and the distinctness of the borders of the lesion. As detailed above, the yield of random biopsies to evaluate for invisible dysplasia has been scrutinized in the era of HD-WLE and other technologies.

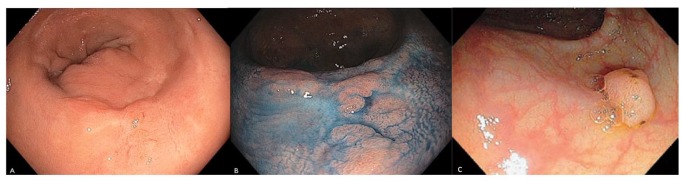

When a lesion that is concerning for dysplasia is identified on endoscopy, the minimum descriptors should include size, morphology (polypoid versus nonpolypoid; Figure 2), border (distinct versus indistinct), and features suggestive of submucosal invasion and invasiveness, including depressed areas, ulceration, or nonlifting with submucosal injection.80 Polypoid lesions, such as those that are pedunculated or sessile, are defined as protruding at least 2.5 mm into the lumen, whereas nonpolypoid lesions, such as those that are slightly elevated, flat, or depressed, may range from superficially elevated to depressed.99 A potentially resectable lesion should have discrete margins that are identifiable and would enable complete resection endoscopically. Biopsies of the tissue surrounding the polyp should be obtained to ensure that the surrounding tissue is free of dysplasia.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic images of non-polypoid (a, b) and polypoid (c) dysplastic lesions. (a, c) WLE; (b) CE.

Photos courtesy of Steven H. Itzkowitz.

CE, chromoendoscopy; WLE, white-light endoscopy.

Management

The management of visible dysplasia in IBD is multidisciplinary and encompasses confirmation by an expert gastrointestinal pathologist, therapeutic resection, medical management to achieve/maintain IBD remission, risk factor modification, low threshold for surgical consultation, and, in the absence of colectomy, continued surveillance (Figure 1). The SCENIC consensus emphasized the importance of distinguishing polypoid from non-polypoid (i.e. flat) lesions, due primarily to therapeutic and prognostic implications, as well as subsequent surveillance considerations.

Non-polypoid lesions have a higher risk of progression to CRC compared with polypoid lesions.100,101 In addition, histologic grade and focality impacts prognosis and subsequent surveillance. For patients for whom en bloc resection of polypoid lesions less than 1 cm is achieved with confirmed negative margins, surveillance colonoscopy is recommended at 12 months.80 For lesions removed piecemeal or with size greater than 1 cm, surveillance colonoscopy should be performed within 3–6 months, with the shorter interval favored for HGD if surgery is not pursued.80 Progression to HGD or CRC following complete resection of unifocal LGD is rare, whereas multifocal LGD carries substantial risk.54,87,102,103 Management following complete resection of a visible lesion with HGD is controversial, and the decision of continuing shorter interval surveillance versus colectomy should be made on a case-by-case basis.80,81,104 Compared with polypoid lesions, the course of non-polypoid lesions following endoscopic resection is not as defined. Classically, non-polypoid dysplasia had been an indication for colectomy. However, in patients for whom complete endoscopic resection of non-polypoid dysplasia is achieved, ongoing surveillance is suggested rather than colectomy, with intervals similar to those recommended for polypoid dysplasia and with similar alterations according to histology and other individual-level factors, including patient preference. Surgical referral should still be discussed with patients, given the higher risk of incomplete resection of non-polypoid lesions with a corresponding higher rate of recurrence and progression of LGD to HGD/CRC compared with polypoid lesions.60

If invisible dysplasia is identified and confirmed by a second pathologist with specific GI expertise, timely referral to an expert in IBD surveillance using CE with HD-WLE is required. If no lesions are identified, random biopsies should be repeated. If LGD is detected randomly, surveillance should be performed every 3–6 months at a minimum; however, surgery should still be discussed with patients given the significant risk of progressing to HGD/CRC.60 In patients with PSC, given the significantly higher risk of progression, there is a much lower threshold for colectomy. If HGD is detected on random biopsies and confirmed by an expert pathologist, a repeat examination should be performed as soon as possible by an endoscopist experienced in IBD dysplasia detection and resection using HD-WLE with CE; if no resectable lesions are identified, colectomy is indicated.

The success of endoscopic resection relies on the achievement of en bloc resection with negative margins. Endoscopic resection techniques include mucosal resection (EMR) and submucosal dissection (ESD), with the latter having only limited data in the IBD population.105–107 If endoscopic resection cannot be reliably achieved, then surgery may be indicated, with the surgery of choice being colectomy in UC or, possibly, segmental resection in Crohn’s colitis depending on disease involvement. Other indications for surgery include any dysplasia in a patient with PSC, a personal history of CRC, severe pseudopolyposis or stricture limiting adequate quality surveillance, or multifocal dysplasia.35

Conclusion

The management of IBD-associated intestinal neoplasia requires careful consideration patient, disease, endoscopic, and histologic factors. Despite the above risk factors and guidelines for CRN in IBD, it is important to recognize that inflammation is dynamic, and surveillance intervals should be based on individual patient factors, cumulative burden of inflammation, and consecutive colonoscopic findings.108 Moreover, there are few data on IBD-related CRN in non-Western populations, and, although recent data from China suggests similar risk factors for the development of CRN in Western populations, future investigations are required to reveal major population differences in risk factors for IBD-related CRN.109 While there have been dramatic improvements in the prevention, identification, and management of colorectal neoplasia in IBD, there are several areas requiring further study. These areas include (a) increasing adherence to recommended quality metrics and surveillance practices; (b) appropriate surveillance intervals tailored to individual patient characteristics and updated to reflect current evidence supporting (cumulative inflammatory burden) or refuting (pseudopolyps) risk determinants; (c) noninvasive biomarker development to complement endoscopy; and (d) efforts to reduce barriers to surveillance, including safely lengthening intervals in those at lowest risk. With the introduction of newer technologies and surveillance modalities, and the expanding population affected by, and aging with, colonic IBD, cost and resource utilization must be considered in tandem with shared patient–physician decision making.

Footnotes

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Writing assistance: No additional writing assistance was used for this manuscript.

ORCID iD: Shailja C. Shah  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2049-9959

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2049-9959

Contributor Information

Jordan E. Axelrad, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at NYU Langone Health, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, NYU School of Medicine, New York, USA

Shailja C. Shah, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 10th floor Rm 1030-C, 2215 Garland Avenue, Medical Research Building IV, Nashville, TN 37203, USA.

References

- 1. Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2010; 28: 573–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet 2018; 390: 2769–2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 720–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 46–54.e42; quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1030–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ullman TA, Itzkowitz SH. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology 2011; 140: 1807–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beaugerie L, Itzkowitz SH. Cancers complicating inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1441–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Munkholm P. Review article: the incidence and prevalence of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 18(Suppl. 2): 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gyde S, Prior P, Dew MJ, et al. Mortality in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1982; 83: 36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 2013; 339: 1546–1558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Axelrad JE, Lichtiger S, Yajnik V. Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: the role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22: 4794–4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Horvath B, Liu G, Wu X, et al. Overexpression of p53 predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and mucosa changes indefinite for dysplasia. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2015; 3: 344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Choi W-T, Rabinovitch PS, Wang D, et al. Outcome of “indefinite for dysplasia” in inflammatory bowel disease: correlation with DNA flow cytometry and other risk factors of colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol 2015; 46: 939–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wen KW, Rabinovitch PS, Wang D, et al. Utility of DNA flow cytometric analysis of paraffin-embedded tissue in the risk stratification and management of “indefinite for dysplasia” in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2019; 13: 472–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yaeger R, Shah MA, Miller VA, et al. Genomic alterations observed in colitis-associated cancers are distinct from those found in sporadic colorectal cancers and vary by type of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2016; 151: 278–287e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med 1988; 319: 525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, et al. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1099–105; quiz 1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, et al. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut 2004; 53: 1813–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chiba T, Marusawa H, Ushijima T. Inflammation-associated cancer development in digestive organs: mechanisms and roles for genetic and epigenetic modulation. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 550–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gerecke C, Scholtka B, Löwenstein Y, et al. Hypermethylation of ITGA4, TFPI2 and VIMENTIN promoters is increased in inflamed colon tissue: putative risk markers for colitis-associated cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2015; 141: 2097–2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Itzkowitz SH, Yio X. Inflammation and cancer IV. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: the role of inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2004; 287: G7–G17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Svrcek M, Piton G, Cosnes J, et al. Small bowel adenocarcinomas complicating Crohn’s disease are associated with dysplasia: a pathological and molecular study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 1584–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adami H-O, Bretthauer M, Emilsson L, et al. The continuing uncertainty about cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2016; 65: 889–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lutgens MWMD, Oijen MGH van, Heijden GJMG van der, et al. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013; 19: 789–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Söderlund S, Brandt L, Lapidus A, et al. Decreasing time-trends of colorectal cancer in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1561–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 645–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jess T, Gamborg M, Matzen P, et al. Increased risk of intestinal cancer in Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 2724–2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jess T, Rungoe C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 639–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Delaunoit T, Limburg PJ, Goldberg RM, et al. Colorectal cancer prognosis among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singh H, Nugent Z, Lix L, et al. 1124 there is no decrease in the mortality from IBD associated colorectal cancers over 25 years: a population based analysis. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: S226–S227. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rubin DT, Huo D, Kinnucan JA, et al. Inflammation is an independent risk factor for colonic neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 1601–1608e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, et al. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 375–381.e1; quiz e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beaugerie L, Svrcek M, Seksik P, et al. Risk of colorectal high-grade dysplasia and cancer in a prospective observational cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2013; 145: 166–175.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kornbluth A, Sachar DB; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College Of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105: 501–523; quiz 524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Itzkowitz SH, Present DH; Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America Colon Cancer in IBD Study Group. Consensus conference: colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005; 11: 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Eaden JA, Abrams KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 2001; 48: 526–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baars JE, Looman CWN, Steyerberg EW, et al. The risk of inflammatory bowel disease-related colorectal carcinoma is limited: results from a nationwide nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bye WA, Nguyen TM, Parker CE, et al. Strategies for detecting colon cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017; 9: CD000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roda G, Narula N, Pinotti R, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: proximal disease extension in limited ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45: 1481–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med 1990; 323: 1228–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shah SC, Ten Hove JR, Castaneda D, et al. High risk of advanced colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16: 1106–1113.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA technical review on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010; 138: 746–774, 774.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reiser JR, Waye JD, Janowitz HD, et al. Adenocarcinoma in strictures of ulcerative colitis without antecedent dysplasia by colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89: 119–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. De Dombal FT, Watts JM, Watkinson G, et al. Local complications of ulcerative colitis: stricture, pseudopolyposis, and carcinoma of colon and rectum. Br Med J 1966; 1: 1442–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lashner BA, Turner BC, Bostwick DG, et al. Dysplasia and cancer complicating strictures in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci 1990; 35: 349–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mahmoud R, Shah S, Ten Hove J, et al. Su1882 - post-inflammatory polyps do not predict colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multinational retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: S-618–S-619. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Choi C-HR, Al Bakir I, Ding N-SJ, et al. Cumulative burden of inflammation predicts colorectal neoplasia risk in ulcerative colitis: a large single-centre study. Gut. Epub head of print 17 November 2017. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fumery M, Pineton de Chambrun G, Stefanescu C, et al. Detection of dysplasia or cancer in 3.5% of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and colonic strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 1770–1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gumaste V, Sachar DB, Greenstein AJ. Benign and malignant colorectal strictures in ulcerative colitis. Gut 1992; 33: 938–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ignjatovic A, Tozer P, Grant K, et al. Outcome of benign strictures in ulcerative colitis. Gut 2011; 60: A221–A222. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mahmoud R, Shah SC, Ten Hove JR, et al. No association between pseudopolyps and colorectal neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 2019; 156: 1333–1344.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eaden JA, Mayberry JF; British Society for Gastroenterology; Association of Coloproctology for Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for screening and surveillance of asymptomatic colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2002; 51(Suppl. 5): V10–V12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Soetikno RM, Lin OS, Heidenreich PA, et al. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 48–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pekow JR, Hetzel JT, Rothe JA, et al. Outcome after surveillance of low-grade and indefinite dysplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 2010; 16: 1352–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Burak K, Angulo P, Pasha TM, et al. Incidence and risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Khaderi SA, Sussman NL. Screening for malignancy in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2015; 17: 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Singh S, Talwalkar JA. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: diagnosis, prognosis, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 11: 898–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Askling J, Dickman PW, Karlén P, et al. Family history as a risk factor for colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2001; 120: 1356–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thomas T, Abrams KA, Robinson RJ, et al. Meta-analysis: cancer risk of low-grade dysplasia in chronic ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007; 25: 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Choi CR, Ignjatovic-Wilson A, Askari A, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: risk factors for developing high-grade dysplasia or colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1461–1471; quiz 1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ullman T, Croog V, Harpaz N, et al. Progression of flat low-grade dysplasia to advanced neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2003; 125: 1311–1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mahmoud R, Shah SC, Torres J, et al. Association between indefinite dysplasia and advanced neoplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases undergoing surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Epub ahead of print 22 August 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Olén O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395: 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Olén O, Erichsen R, Sachs MC, et al. Colorectal cancer in Crohn’s disease: a Scandinavian population-based cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. Epub ahead of print 13 February 2020. DOI: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jess T, Loftus EV, Velayos FS, et al. Risk of intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study from olmsted county, Minnesota. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bernstein CN, Blanchard JF, Kliewer E, et al. Cancer risk in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Cancer 2001; 91: 854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Winther KV, Jess T, Langholz E, et al. Long-term risk of cancer in ulcerative colitis: a population-based cohort study from Copenhagen county. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2: 1088–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Söderlund S, Granath F, Broström O, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease confers a lower risk of colorectal cancer to females than to males. Gastroenterology 2010; 138: 1697–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Jess T, Riis L, Vind I, et al. Changes in clinical characteristics, course, and prognosis of inflammatory bowel disease during the last 5 decades: a population-based study from Copenhagen, Denmark. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007; 13: 481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Macdougall IM. The cancer risk in ulcerative colitis. Lancet 1964; 284: 655–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Prior P, Gyde SN, Macartney JC, et al. Cancer morbidity in ulcerative colitis. Gut 1982; 23: 490–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gyde SN, Prior P, Macartney JC, et al. Malignancy in Crohn’s disease. Gut 1980; 21: 1024–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Lutgens MWMD, Oldenburg B, Siersema PD, et al. Colonoscopic surveillance improves survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Cancer 2009; 101: 1671–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Choi PM, Nugent FW, Schoetz DJ, et al. Colonoscopic surveillance reduces mortality from colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1993; 105: 418–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010; 138: 738–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002). Gut 2010; 59: 666–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2013; 7: 982–1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Standards of Practice Committee, Shergill AK, Lightdale JR, et al. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81: 1101–1121.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Harbord M, Eliakim R, Bettenworth D, et al. Corrigendum: third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis 2017; 11: 1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, et al. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 81: 489–501.e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Annese V, Beaugerie L, Egan L, et al. European evidence-based consensus: inflammatory bowel disease and malignancies. J Crohns Colitis 2015; 9: 945–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gearry RB, Wakeman CJ, Barclay ML, et al. Surveillance for dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a national survey of colonoscopic practice in New Zealand. Dis Colon Rectum 2004; 47: 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kaplan GG, Heitman SJ, Hilsden RJ, et al. Population-based analysis of practices and costs of surveillance for colonic dysplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007; 13: 1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Eaden JA, Ward BA, Mayberry JF. How gastroenterologists screen for colonic cancer in ulcerative colitis: an analysis of performance. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51: 123–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rijn AF, van, Fockens P, Siersema PD, et al. Adherence to surveillance guidelines for dysplasia and colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis patients in the Netherlands. WJG 2009; 15: 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Iannone A, Ruospo M, Wong G, et al. Chromoendoscopy for surveillance in ulcerative colitis and crohn’s disease: a systematic review of randomized trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15: 1684–1697e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ten Hove JR, Mooiweer E, Meulen de, Jong AE, van der, et al. Clinical implications of low grade dysplasia found during inflammatory bowel disease surveillance: a retrospective study comparing chromoendoscopy and white-light endoscopy. Endoscopy 2017; 49: 161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Moussata D, Allez M, Cazals-Hatem D, et al. Are random biopsies still useful for the detection of neoplasia in patients with IBD undergoing surveillance colonoscopy with chromoendoscopy? Gut 2018; 67: 616–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jegadeesan R, Desai M, Sundararajan T, et al. P172 chromoendoscopy versus high definition white light endoscopy for dysplasia detection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: S93. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Yang D-H, Park SJ, Kim H-S, et al. High-definition chromoendoscopy versus high-definition white light colonoscopy for neoplasia surveillance in ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114: 1642–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dekker E, Broek FJ, van den, Reitsma JB, et al. Narrow-band imaging compared with conventional colonoscopy for the detection of dysplasia in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy 2007; 39: 216–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Pellisé M, López-Cerón M, Rodríguez de, Miguel C, et al. Narrow-band imaging as an alternative to chromoendoscopy for the detection of dysplasia in long-standing inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, randomized, crossover study. Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 74: 840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Iacucci M, Kaplan GG, Panaccione R, et al. A randomized trial comparing high definition colonoscopy alone with high definition dye spraying and electronic virtual chromoendoscopy for detection of colonic neoplastic lesions during IBD surveillance colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114: 384–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Broek FJC, van den, Stokkers PCF, Reitsma JB, et al. Random biopsies taken during colonoscopic surveillance of patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis: low yield and absence of clinical consequences. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rubin DT, Rothe JA, Hetzel JT, et al. Are dysplasia and colorectal cancer endoscopically visible in patients with ulcerative colitis? Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 65: 998–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Lahiff C, Mun Wang L, Travis SPL, et al. Diagnostic yield of dysplasia in polyp-adjacent biopsies for patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a cross-sectional study. J Crohns Colitis 2018; 12: 670–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Anonymous. The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 58: S3–S43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Endoscopic Classification Review Group. Update on the paris classification of superficial neoplastic lesions in the digestive tract. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 570–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Wanders LK, Dekker E, Pullens B, et al. Cancer risk after resection of polypoid dysplasia in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Voorham QJM, Rondagh EJA, Knol DL, et al. Tracking the molecular features of nonpolypoid colorectal neoplasms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 1042–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Navaneethan U, Jegadeesan R, Gutierrez NG, et al. Progression of low-grade dysplasia to advanced neoplasia based on the location and morphology of dysplasia in ulcerative colitis patients with extensive colitis under colonoscopic surveillance. J Crohns Colitis 2013; 7: e684–e691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Zisman TL, Bronner MP, Rulyak S, et al. Prospective study of the progression of low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis using current cancer surveillance guidelines. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 2240–2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans JA, Chandrasekhara V, et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of premalignant and malignant conditions of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 82: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Iacopini F, Saito Y, Yamada M, et al. Curative endoscopic submucosal dissection of large nonpolypoid superficial neoplasms in ulcerative colitis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 82: 734–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Suzuki N, Toyonaga T, East JE. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of colitis-related dysplasia. Endoscopy 2017; 49: 1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Kinoshita S, Uraoka T, Nishizawa T, et al. The role of colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 87: 1079–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Shah SC, Itzkowitz SH. Reappraising risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease-associated neoplasia: implications for colonoscopic surveillance in IBD. J Crohns Colitis. Epub ahead of print 9 March 2020. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wu X-R, Zheng X-B, Huang Y, et al. Risk factors for colorectal neoplasia in patients with underlying inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter study. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf) 2019; 7: 67–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]