Abstract

Shared decision making is a strategy to achieve health equity by strengthening patient-provider relationships and improve health outcomes. There is a paucity of research examining these factors among patients who identify as sexual or gender minorities and racial/ethnic minorities. Through intrapersonal, interpersonal and societal lenses, this project evaluates the relationship between intersectionality and shared decision making around anal cancer screening in Black gay and bisexual men, given their disproportionate rates of anal cancer. Thirty semi-structured, one-on-one interviews and two focus groups were conducted from 2016–2017. Participants were asked open-ended questions regarding intersectionality, relationships with healthcare providers and making shared decisions about anal cancer screening. 45 individuals participated; 30 in individual interviews and 15 in focus groups. All participants identified as black and male. 13 identified as bisexual and 32 as gay. Analysis revealed that the interaction of internalized racism, biphobia/homophobia, provider bias and medical apartheid lead to reduced healthcare engagement and discomfort with discussing sexual practices, potentially hindering patients from engaging in shared decision making. Non-judgmental healthcare settings and provider relationships in which patients communicate openly about each aspect of their identity will promote effective shared decision making about anal cancer screening, and thus potentially impact downstream anal cancer rates.

Keywords: shared decision making, anal cancer screening, intersectionality, gay, bisexual, LGBT, Black men

Introduction

Shared decision making is the collaborative process through which individuals and providers arrive at treatment plans that take into account the patient’s needs and preferences (Peek et al. 2016). Shared decision making has been identified as a key intervention to improve clinical outcomes through effective patient-provider communication (Peek et al. 2016; Stewart 1995). Differences in communication and shared decision making among racial/ethnic minorities may contribute to ongoing healthcare disparities (Johnson et al. 2004; Institute of Medicine 2003; Betancourt 2003). While shared decision-makingholds promise as a tool to combat healthcare disparities, there is insufficient knowledge on how it can be implemented effectively within marginalised populations. Further, persons from multiple oppressed groups are at even higher risk of suffering from healthcare disparities (Institute of Medicine 2011; Hatzenbuehler, Phelan and Link 2013).

The intersection of identities in a matrix of domination, and the interlocking, multiple systems of social stratification (e.g., racism, sexism, heteropatriarchy) that influence an individual’s lived experience, can have a profound effect on health and well-being, particularly for multiply disadvantaged persons (Peek et al. 2016). Rooted in Black Feminist theory, intersectionality clarifies the ways in which multiple social identities intersect to contribute to the total amount of social advantage or disadvantage a person experiences in their everyday life. These advantages and disadvantages are distributed through a matrix of domination that privileges membership in certain social groups (e.g., people of European descent, cisgender heterosexual males, people with light skin tones, etc.) over others (e.g., people of colour, transgender people, people with dark skin tones, people who are bisexual or gay, etc.) (Limpangog 2016). Holding membership in multiple disadvantaged groups can contribute to compounded discrimination. Cultural factors such as masculinity and religious belief may also contribute to perpetuation of discrimination (Fields 2016).

There are important gaps in the literature on specific conditions or experiences that impact on the health of sexual and gender minority andracial/ethnic minority populations. A systematic review by Peek et al. (2016) found very little literature that addressed shared decision making among sexual and gender minority Black (i.e. dual minority) populations. In this analysis we chose to focus on anal cancer screening, given increasing evidence that there may be both disparities in how anal cancer presents in Black bisexual and gay men and that few of these men may be engaged in the screening process (Walsh,Bertozzi-Villa and Schneider 2015). Additionally, shared decision making can be particularly useful in situations in which the patient and provider can choose more than one reasonable option, which is true for anal cancer screening and will be described below. This project aims to identify ways to improve SDM between Black bisexual and gay men and their providers around anal cancer screening.

Anal cancer incidence in the USA is increasing, with several populations being at particularly high risk, especially bisexual and gay men living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The incidence rate of anal cancer in the general population is 2.2 cases per 100,000 women and 1.3 cases per 100,000 men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control”HPV-Associated Anal Cancer” 2018). Gay and other men who have sex with men are a high-risk population for anal cancer (van der Zee et al. 2013). The incidence rate of anal cancer among HIV-negative men who have sex with men is 40 cases per 100,000 (Margolies and Goeren 2009). However, HIV positivemen who have sex with men have been reported to have an incidence between 75 to 137 per 100,000 (Piketty et al. 2008; D’Souza 2008; Patel et al. 2008). In terms of race/ethnicity, Black men have the highest incidence of anal cancer and related mortality in the USA (Ashktorab 2017). Amongmen who sex with men Black men are reported to have a higher prevalence of HPV infection, dysplasiaand cancer than other groups (Walsh, Bertozzi-Villa and Schneider 2015). Furthermore, Black men who have sex with menare at particularly high risk for anal cancer given high rates of HIV (Kaplan et al.2009; Tong et al. 2014; Chiao 2006). Yet, Black men are less likely to be offered and undergo anal cancer screening for unknown reasons (Walsh,Bertozzi-Villa and Schneider 2015; D’Souza et al. 2013). These findings highlight a need to delve into this topic further to understand what is occurring on the level of the patient-provider interaction that may be contributing to the screening disparities.

In addition to the disparities that exist within anal cancer screening, there is uncertainty within the medical community as to the best approach for screening, which makes SDM between the provider and patient all the more important (Katz et al. 2009; Katz et al. 2010; Leeds and Fang 2016). Some experts, including the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, recommend screening for anal cancer among MSM and all HIV+ persons due to the increasing morbidity and mortality from anal cancer (Aberg 2014). Other organisations, including the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have not recommended routine anal cancer screening (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. “Preventing HPV-Associated Cancers.”2018). Of clinicians performing anal cancer screening, some recommend annual digital ano-rectal exam, while others recommend anal cytology (anal Pap) and others even recommend annual high-resolution anoscopy (Kaplan et al. 2009). The lack of national recommendations for routine screening of anal cancer in high-risk patients is mainly due to lack of data on improved outcomes through screening (Ortoski and Kell 2011; Wells et al. 2014; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of STD Prevention 2016). Given the evolving nature of the field, a shared decision makingapproach is crucial for patients to fully understand the options and the potential benefits and risks of each. This uncertainty as to the most appropriate recommendation for screening can affect the relationship between Black MSM and their providers and may be shaped by the historical experiences of Black men with the healthcare system.

Black men have experienced many forms of oppression that contribute to negative experiences within the healthcare system (Plaisime et al. 2017). Segregation according to socioeconomic status has created a system of medical apartheid1 in which persons of colour suffer increased morbidity and mortality from a wide range of conditions due to being uninsured or underinsured with poor access to care (Washington 2006; Brooks, Smith and Anderson 1991). The history of medical apartheid in the form of unwanted experimentation can affect Black individuals’ feelings of trust in their healthcare providers, which can in turn cause avoidance of care, hindering the ability to participate openly in shared decision making, and leading to reluctance to undergo necessary treatment (Jacobs et al. 2006). This legacy of white racial domination contributes to internalised racism in Black men, and Black bisexual and gay men have an added layer of external and internalised biphobia/homophobia (Gamble 1997; Herek, Chopp and Strohl 2007). Therefore, we aim to interpret the findings around shared decision making within these historical, social, and cultural contexts.

Conceptual Model

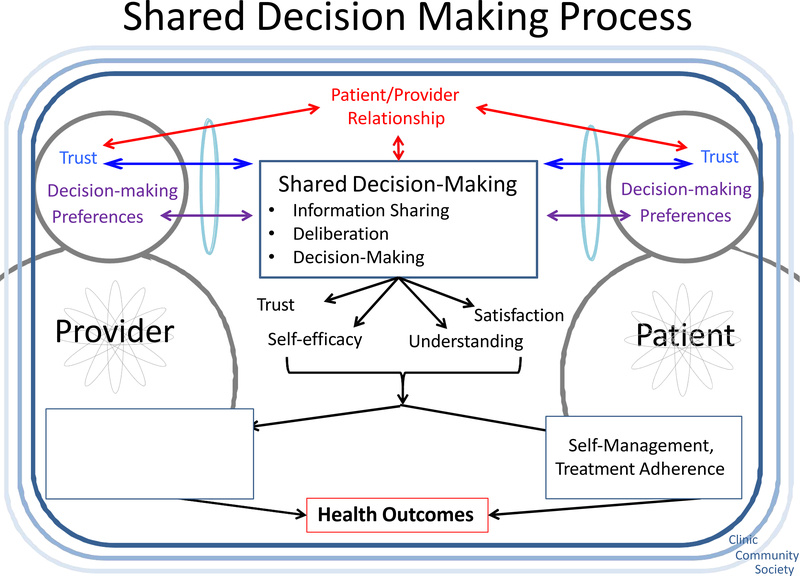

We used the Peek Model for Shared Decision Making (Figure 1) (Peek et al. 2016) as the framework for this project. In this model, patient, provider and their relationship are viewed within multiple constructs. At the individual level, provider and patient have multiple identities of race, ethnicity/culture, sexuality, gender, age, socioeconomic status, etc. These identities are influenced and moulded through perceptions, which are, in part, the internalisation of community and society’s views on these identities, shaped by personal lived experience of social advantage and/or disadvantage. Both the patient and the provider bring their own identity and self-perception to the encounter, which in turn affects the interactions and relationship (Peek et al. 2016).

Figure 1.

Peek Model for Shared Decision Making.

In addition to self-perception, provider and patient perceive the other based on known or assumed identities and roles during the patient-provider encounter. This perception occurs through lenses of stereotypes, prejudices, implicit biases and normative beliefs, as influenced by lived experiences and the community and social contexts (Peek et al. 2016). These lived experiences are also apparent in the clinical encounter, influencing actions and communication between patient and provider.

The provider’s and patient’s social identities and perceptions of others influence SDM. Patients’ and providers’ ability to engage in shared decision making is determined by their individual preferences, mutual trust and existing relationship. Successful shared decision making results in bidirectional outcomes of improved self-efficacy, trust, understanding and satisfaction that can lead to improved self-management and treatment adherence on the part of the patient as well as job satisfaction, patient-centred care and cultural competence on the part of the provider. Ultimately, these outcomes can improve care delivery to the benefit of patient health (Peek et al.2016).

Materials and Methods

Setting and Participants

Thirty individual interviews and two focus groups were conducted at multiple sites in the city of Chicago, Illinois between 2016–2017 (n=45). A multipronged approach to recruitment was taken, including launch events and flyers at local health centres, social media outlets like Facebook and Twitter, newspaper ads and outreach at events that focus on sexual and gender minorities. All participants were at least 18 years of age, identified as cisgender men and Black, and reported current or past sex with other men. Participants were excluded if they did not meet these criteria. Participants received food, water, and a $40 cash stipend upon completion of the interview. All participants provided informed verbal consent. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Chicago.

Data Collection

Thirty semi-structured in-person interviews and 2 focus groups lasting 60–90 minutes in length were conducted in English. 15 individuals participated in focus groups. In-person interviews were offered to allow participants the privacy to speak on sensitive subjects, such as anal cancer screening and HIV. However, focus groups were also performed so that participants could listen to others’ experiences and comment on any similarities or differences. Participants completed a self-administered survey at the beginning of each session with items on demographics, health behaviours, and healthcare experiences. A copy of the survey instrument is available in an online appendix. Trained community members conducted interviews and functioned as focus group moderators. Interviewers were provided with a loose script to follow in the form of an interview guide. Questions were designed to promote discussion, and interviewers were encouraged to probe for additional information if clarification was needed. The interview and focus group questions were developed around Peek et al.’s (2016) model for shared decision making. Questions focused on intersectionality, healthcare experiences, disclosure of sexual identity, information sharing around anal cancer screening, decisions about anal cancer screening, and advice for healthcare providers. Participants were given information on community resources for LGBTQ persons of colour at the end of the session.

Measures and Analysis

All interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and professionally transcribed. The data were analysed using modified template approach (Crabtree and Miller 1999), in which themes were identified as they emerged from the data. An initial codebook was prepared with themes based on the interview guides and was refined throughout analysis. Three members of the research team independently coded each transcript. Discrepancies were discussed to agreement. As new codes were identified and added to the codebook, all transcripts were reviewed for these new themes. Once all coding was completed, transcripts were imported into HyperRESEARCH 3.7.4 qualitative software, which is designed to organise coded text. Coded text was reviewed and analysed. Themes emerged and illustrative quotes were selected.

Findings

Participants’ self-reported sociodemographic and health characteristics are shown in Table 1. 45 participants completed the survey instrument. Of those, 13 (28.9%) identified as bisexual, while 32 (71.1%) described themselves as gay. All participants identified as male and Black, of which 35 (77.8%) described themselves as African American, while 10 (22.2%) described themselves as multiracial. Of participants who reported employment status, the majority reported that they were either unable to work or unemployed (n=26, 59.1%), with an annual income less than $20,000 (73.8%). 37 (84.1%) participants reported public insurance as their primary health insurance. Self-reported HIV positive status was found in the majority of participants (29 (64.4%)). Participants’ names used in quotes below are pseudonyms in order to protect their confidentiality.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Health Characteristics of Your Voice! Your Health! Anal cancer sub-study participants (n=45) 2016–2017, Chicago.

| All (n=45) | Bisexual (n=13) | Gay (n=32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Male* | 45 (100) | 13 (28.9) | 32 (71.1) |

| Age group§ | |||

| ≤ 30 years | 4 (12.1) | 2 (25.0) | 2 (8.0) |

| 31–50 years | 17 (51.5) | 1 (12.5) | 16 (64.0) |

| > 50 years | 12 (36.4) | 5 (62.5) | 7 (28.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black | 45 (100) | 13 (100) | 32 (100) |

| African American | 35 (77.8) | 10 (76.9) | 26 (81.1) |

| Multiracial | 10 (22.2) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (18.8) |

| Education | |||

| < 12th grade | 4 (8.9) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (3.1) |

| High school or General Education Diploma | 9 (20.0) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (25.0) |

| Some college/2-year degree | 22 (48.9) | 5 (38.5) | 17 (53.1) |

| 4+ years of college | 10 (22.2) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (18.8) |

| Employment status§† | |||

| Full time | 7 (15.9) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (16.1) |

| Part time | 9 (20.5) | 2 (15.4) | 7 (22.6) |

| Student | 2 (4.6) | 2 (15.4) | 0 |

| Unable to work | 15 (34.1) | 4 (30.8) | 11 (35.5) |

| Unemployed | 11 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 8 (25.8) |

| Annual income§ | |||

| < $20,000/Not employed | 31 (73.8) | 9 (75.0) | 22 (73.3) |

| $20,000 – $50,000 | 9 (21.4) | 1 (8.3) | 8 (26.7) |

| > $50,000 | 2 (4.8) | 2 (16.7) | 0 |

| Health insurance§ | |||

| Private | 7 (15.9) | 2 (16.7) | 5 (15.6) |

| Medicaid and/or Medicare | 37 (84.1) | 10 (83.3) | 27 (84.4) |

| Regular healthcare provider | 44 (97.8) | 13 (100.0) | 31 (96.9) |

| Discussed anal cancer screening | 28 (62.2) | 7 (53.8) | 21 (65.6) |

| Self-perceived health status§ | |||

| Excellent/ Very Good | 26 (59.1) | 9 (75.0) | 17 (53.1) |

| Good | 11 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) | 10 (31.3) |

| Fair/ Poor | 7 (15.9) | 2 (16.7) | 5 (15.6) |

| HIV+ | 29 (64.4) | 8 (61.5) | 21 (65.6) |

| History of STI | 19 (42.2) | 6 (46.2) | 13 (40.6) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Daily | 17 (37.8) | 5 (38.5) | 12 (37.5) |

| Occasionally | 9 (20.0) | 1 (7.7) | 8 (25.0) |

| Not at all | 19 (42.2) | 7 (53.8) | 12 (37.5) |

Percentages are calculated out of the column totals except for this variable.

Variable categories may not add up to total N due to missing data.

Participants were able to choose more than one option.

Internalised biphobia and homophobia

Psychological distress resulting from internalised biphobia/homophobia may contribute to decreased health-seeking behaviours and reduced healthcare engagement. Many participants described experiences of biphobia/homophobia within the Black community.

(Marion, gay, individual interview, declined to provide age)…the south side where I grew up, it’s very homophobic and Black people are, our culture, we’re really into the church and condemnation about homosexuality…They have their own impression of what gay… means and I had an aunt that told me…I don’t mind you people being gay but why do you have to march in that parade where everybody can see you…if you are gay, you have to keep it in the closet and act like a straight man.

Experiences of biphobia/homophobia at the interpersonal and contextual levels may be consequences of historical racialised oppression (Williams 2016). External forces of discrimination and stigma are then often internalised, which may lead to intrapersonal conflict for dual minority study participants.

Recognition of sexual and racial identities and their intersection by providers may help facilitate shared decision making. One participant described the experience of providers addressing either race or sexual identity but not both simultaneously. This imposed fragmentation of identity can limit patient-provider trust and hinder effective shared decision making.

(Essex, gay, individual interview, age 30)…now having to deal with that dual identity and oftentimes not wanting to face what that means and having that dual identity. And oftentimes I think it’s presented where they [healthcare providers] make you or put you in a box where you’re choosing between the two depending on what the particular circumstance is, instead of making it more comprehensive. So, it’s not like I’m choosing to be Black on this day and I’m choosing to be gay on this day, but both are facets of who I am.

For some men, the experience of having multiple oppressed identities compounds the experience of oppression because one may experience marginalisation for multiple reasons simultaneously, or different forms of marginalisation across multiple contexts. Both of these kinds of experiences of oppression can wear a person down.

Provider racial bias, medical apartheid, and internalised racism

Healthcare engagement may be weakened as a consequence of oppression and disparities within the medical system. Eight individuals described the practice of Black men being reluctant to engage in healthcare and being unwilling trust healthcare providers as a consequence of the cultural memory of medical experimentation as well as ongoing healthcare disparities.

(Max, gay, focus group participant, age 38) As African-American individuals, we have just had a fear of going to the doctor, we have a fear of taking care of our health because we have been treated in certain way from the past and being experimented on.

Five individuals reported that members of the Black community are more likely to experience provider bias and racial prejudice. Five participants reported a belief that white people, including White gay men, receive more information and superior medical treatment than Black people.

(Joseph, gay, individual interview, age 34) …there is a difference between being a Black, gay male and having not the greatest insurance and being a white gay man and having some insurance. I think you are going to get better service, you’re going to get more knowledge of what is going on… I think that if this is a Black gay male…you are less likely to get the information that is needed unless you are empowered to go in and demand it for yourself.

Marion (gay, individual interview, declined to provide age) also reported racial prejudice, ‘…some of [healthcare providers] automatically have this perception that Black men in particular are invincible…we can take more pain and you know torture or diseases…’James (bisexual, focus group participant, age 40) experienced racial prejudice in the act of being put on display in the examination room. ‘She started bringing new people into the room and… not being concerned about whether this made me comfortable…and I was reminded that I am a nigga, even with light eyes, light-skinned, I am still a nigga…’ This experience of provider prejudice by being put on display is consistent with a cultural memory of slavery auction block examinations that is deeply painful and may further diminish healthcare engagement (Bailey 2017).

Internalised racism that decreases healthcare-seeking behaviours coupled with the sensitive nature of discussing sexual identity and sexual practices may further decrease the likelihood of a Black bisexual or gay man discussing anal cancer screening with a healthcare provider, particularly those men with internalised biphobia/homophobia.

(Essex, gay, individual interview, age 30) …we already as African American community alone have issues with healthcare providers…a lot of people are just uncomfortable disclosing their sexual... especially their sexual identity or what they do or what may make them feel that they’re at risk for some of those things.

Vulnerability and provider prejudice

Since anal cancer is more prevalent among bisexual and gay men, particularly those who are HIV positive, having a conversation with a provider about anal cancer screening often involves discussing sexual orientation and sexual practices (Table 2). Of the 45 survey respondents, 69.3% of bisexual men and 90.7% of gay men were open about their sexual identity with their current healthcare provider. Approximately 77.3% of bisexual and gay men felt respected by their current provider.

Table 2.

Healthcare Experiences of Your Voice! Your Health! Participants (n=45)

| Question* | All (n=45) | Bisexual (n=13) | Gay (n=32) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open about sexual orientation with providers | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Strongly agree | 28 (62.2) | 5 (38.5) | 23 (71.9) |

| Agree | 10 (22.2) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (18.8) |

| Neutral | 3 (6.7) | 3 (23.1) | 0 |

| Disagree | 2 (4.4) | 0 | 2 (6.2) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (2.2) | 1 (7.7) | 0 |

| Does not apply to me | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 1 (3.1) |

| Feel respected by providers§ | |||

| Strongly agree | 22 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 16 (51.6) |

| Agree | 12 (27.3) | 4 (30.8) | 8 (25.8) |

| Neutral | 6 (13.6) | 2 (15.4) | 4 (12.9) |

| Disagree | 3 (6.8) | 1 (7.7) | 2 (6.5) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (3.2) |

| Does not apply to me | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seek out sexual and gender minority-friendly providers§ | |||

| Strongly agree | 16 (36.4) | 5 (38.5) | 11 (35.5) |

| Agree | 7 (15.9) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (16.1) |

| Neutral | 10 (22.7) | 3 (23.1) | 7 (22.6) |

| Disagree | 7 (15.9) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (16.1) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (3.2) |

| Don’t know/no experience | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (3.2) |

| Does not apply to me | 2 (4.6) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (3.2) |

| Seek out providers of my own race/ethnicity§ | |||

| Strongly agree | 4 (9.1) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (6.5) |

| Agree | 7 (15.9) | 4 (30.8) | 3 (9.7) |

| Neutral | 15 (34.1) | 5 (38.5) | 10 (32.3) |

| Disagree | 8 (18.2) | 1 (7.7) | 7 (22.6) |

| Strongly disagree | 6 (13.6) | 1 (7.7) | 5 (16.1) |

| Don’t know/no experience | 1 (2.3) | 0 | 1 (3.2) |

| Does not apply to me | 3 (6.8) | 0 | 3 (9.7) |

| Have had a visit with my provider where I needed to make a decision about my health | |||

| Yes | 42 (93.3) | 11 (84.6) | 31 (96.9) |

| No | 3 (6.7) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (3.1) |

| Provider asked me which treatment option I prefer§ | |||

| Completely disagree | 3 (7.3) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (6.5) |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (9.8) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (9.7) |

| Somewhat disagree | 3 (7.3) | 0 | 3 (9.7) |

| Somewhat agree | 5 (12.2) | 0 | 5 (16.1) |

| Strongly agree | 9 (22.0) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (19.4) |

| Completely agree | 17 (41.5) | 5 (50.0) | 12 (38.7) |

| Provider and I reached an agreement on how to proceed§ | |||

| Completely disagree | 3 (7.3) | 0 | 3 (9.7) |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (9.8) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (9.7) |

| Somewhat disagree | 2 (4.9) | 0 | 2 (6.5) |

| Somewhat agree | 4 (9.8) | 0 | 4 (12.9) |

| Strongly agree | 9 (22.0) | 3 (30.0) | 6 (19.4) |

| Completely agree | 19 (46.3) | 6 (60.0) | 13 (41.9) |

| Providers have treated me differently from other patients† | |||

| Never | 32 (71.1) | 12 (92.3) | 20 (62.5) |

| Due to biphobia/homophobia | 3 (6.7) | 0 | 3 (9.4) |

| Due to discrimination against people living with HIV | 3 (6.7) | 0 | 3 (9.4) |

| Due to race or ethnicity | 4 (8.9) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (9.4) |

| Happened for other reasons | 5 (11.1) | 0 | 5 (15.6) |

| Providers have blamed me for my health status§† | |||

| Never | 36 (80.0) | 11 (84.6) | 25 (78.1) |

| Due to biphobia/homophobia | 2 (4.4) | 0 | 2 (6.3) |

| Due to discrimination against people living with HIV | 4 (8.9) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (9.4) |

| Due to race or ethnicity | 2 (4.4) | 0 | 2 (6.3) |

| Happened for other reasons | 1 (2.2) | 0 | 1 (3.1) |

Question and response options have been shortened; please see online Appendix for full survey questions.

Variable categories may not add up to total N due to missing data.

Participants were able to choose more than one option; thus percentages may not add up to 100%.

Discussion about sexual orientation and sexual practices can create a sense of vulnerability among patients, which is potentially further heightened by an anal examination. Twelve participants experienced prejudice on at least one occasion from healthcare providers about their sexual practices and sexual identity and fifteen participants feared the judgement and vulnerability that accompanies a conversation about their sexuality.

(Joseph, gay, individual interview, age 34) They [providers] automatically assume that all gay men…receive anal sex. Some people assume that gay men are just so promiscuous, and we’re just out here doing any and everybody, any and everything.

Exercising agency in the setting of uncertainty

61.4% (n=27) of study participants reported anal cancer screening discussions with healthcare providers. The majority of those discussions occurred with a personal healthcare provider, while some occurred in the context of another research study investigating the management of pre-cancerous anal lesions in HIV positive men and women.

The majority of participants who had discussions about anal cancer screening prided themselves as being the primary decision maker. Of 40 survey respondents, 26 agreed that they vocalise their opinions to providers about diagnostic tests and treatment, and 27 either strongly or completely agreed that they have reached an agreement on a medical plan with their doctor (Table 2).

(Essex, gay, individual interview, age 30) I make it a habit of educating myself and bringing my own questions, bringing my own concerns. And even if they don’t agree, I push for my stance because, at the end of the day, this is my life. It’s my health and I have to take control of that.

Most participants stated that their opinions were valued, and they were satisfied with the decisions made about anal cancer screening. Although most identified themselves as the primary decision-maker, nearly all of the participants stated that the provider’s and the patient’s viewpoints are equally important in decision-making about anal cancer screening.

(Assotto, gay, individual interview, age 37) I think it’s fairly equal because I think the patient needs to be an equal contributor to their overall health as well as the doctor...the doctor needs to listen to the patient. The patient needs to listen to the doctor and find a nice, healthy medium…

Among HIV positive participants, many reported a feeling of responsibility for self-education, as well as a desire for the provider to share as much knowledge about anal cancer screening as possible. This belief in self-education may be related to prior experiences with HIV diagnosis and treatment.

Despite the desire for agency among study participants, anal cancer screening is an area with many unanswered questions for both patients and providers. This uncertainty may create a challenge for participants wishing to exercise their agency and make informed decisions about their healthcare. Currently, no national guidelines exist about when to screen and how to act on abnormal results (Leeds and Fang 2016; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of STD Prevention 2016), which can complicate how providers discuss anal cancer with patients.

In the setting of uncertainty, there are often several options for patients to consider. Nearly all study participants stated that they prefer to hear all options rather than the provider’s number one recommendation. (Samuel, gay, individual interview, age 53) ‘…I would like to be presented with all the options, but I will also listen to what my doctor thinks as well and then I will weigh them.’ There were mixed reactions from participants about the presence of uncertainty. Thirteen participants stated that their decision to undergo anal cancer screening would not change despite uncertainty. In contrast, five participants reported that uncertainty about the effectiveness of anal cancer screening would make them less likely to get screened. (Kwasi, bisexual, individual interview, declined to provide age)’When I hear the part about there’s no certainty…I’m reluctant to do something.’

Culturally competent, face-to-face communication

The majority of participants expressed a desire for culturally competent providers who listen to patients and are sensitive to issues affecting bisexual and gay men. (Melvin, gay, individual interview, age 25)’Well, first you have to choose a provider that is accepting, that shows no judgement, that is open to talking about any and everything.’ Another participant stated,

(Malcolm, bisexual, individual interview, declined to provide age) …if they have not been in the LGBT community or have not worked with Black, African-American men, it would be helpful for them to know, too, like the cultural significance, sort of like a cultural competency.

Many participants stated that it was important for their provider to know their sexual orientation in order to provide the best possible healthcare.

(Essex, gay, individual interview, age 30) …in order for me to receive comprehensive healthcare services and to receive the care that I need, my provider needs to be aware of any potential risk, background, whatever it is that’s going on with me, so that we can create the best comprehensive healthcare plan for me.

All participants valued face-to-face communication above all other forms of communication. Written communication was believed to be helpful by 78.6% of participants. 63.2%, 59.1% and 36.4% of participants valued community health-workers, web-based communication and phone communication, respectively. Study participants were clear that providers need education on anal cancer screening and need to be comfortable sharing that knowledge with patients.

(Joseph, gay, individual interview, age 34)…it’s their responsibility as a healthcare provider to provide you with information…It’s like, if you don’t mention it, probably a layperson or a regular person is not going to know that there’s an anal cancer screening available for them.

In addition, telephone conversations and sharing of information over the Internet, via email or websites, were not desirable forms of communication for many participants due to concerns over privacy.

Discussion

When aspects of identity interact, vulnerability can be heightened. Multiply oppressed people are more likely to report discrimination, psychological distress and worse self-rated health than their singly oppressed contemporaries (Peek et al. 2016; Gayman and Barragan2013; Mays and Cochran 2001; Grollman 2012, 2014; Meyer, Schwartz and Frost 2008). In the Peek et al. (2016) conceptual model, relationships between trust, individualdecision-making preferences and the quality of the patient-provider interaction mould the shared decision making experience. Lack of healthcare engagement and poor health outcomes are downstream events that can result from providers’ failure to recognise the role of intersectionality in shared decision making.

As previously mentioned, risk factors for anal cancer include receptive anal intercourse and HIV infection, among others (van der Zee et al. 2013; Margolies and Goeren 2009; Piketty et al. 2008; D’Souza 2008; Patel et al. 2008; Ashktorab 2017; Kaplan et al. 2009; Tong et al. 2014; Chiao 2006). Given that Black men are disproportionately burdened by HIV, those who also engage in anal receptive sex are at especially high risk for anal cancer (Walsh, Bertozzi-Villa and Schneider 2015). Discussing sexual practices is key to accurately identifying patients who may benefit from anal cancer screening. Our data suggest that the matrix of domination and the cultural memory of medical apartheid were catalysts for internalised racism and biphobia/homophobia, reduced healthcare engagement, and discomfort with discussing sexual practices. Experiences of anti-Blackness and biphobia/homophobia can degrade Black men’s belief that good health and receipt of quality healthcare is possible. Additionally, binegative/homonegative cultural expectations from within the Black community can lead to subconscious repression of sexual identity (Fields, Morgan and Sanders 2016). To navigate those expectations and avoid binegativity/homonegativity, Black bisexual and gay men may subconsciously allow their racial identity to be dominant and their sexual identity to be subordinate. By so doing, Black bisexual and gay men may maintain supportive relationships within the Black community that would otherwise be challenged by a perception of weakness and femininity (Fields, Morgan and Sanders 2016). As religion is often prominent in Black communities, faith-based binegativity/homonegativity can also lead to the suppression of sexual identity, internalisation of biphobia/homophobia and gradual degradation of supportive community relationships (Fields 2015). A consequence of reduced healthcare engagement and discomfort with disclosing sexual practices is that patients at higher risk for anal cancer often may not be identified by providers and may not be able to engage in effective shared decision making about anal cancer screening.

Our data show that Black bisexual and gay men often wish to be open about their sexual orientation with sensitive, culturally competent providers in face-to-face communication. Providers wishing to build strong and collaborative relationships with their Black bisexual and gay patients should ensure their cultural competency through education. Providers should also carefully observe for their own stereotypes, prejudices and implicit biases that are brought to the clinical encounter often in the form of expectations. Among healthcare providers, awareness should be raised of the vulnerability of Black patients who face both internalised racism and internalised biphobia/homophobia, as this potentially can lead to worse mental and physical health outcomes. Creating safe, non-judgmental spaces for patients to communicate openly about each aspect of their identity can promote disclosure of sexual identity and sexual practices and effective shared decision making, which is necessary to providing comprehensive and appropriate medical care, including anal cancer screening. Importantly, our data suggest that providers should recognise the desire among many of their patients to be the primary healthcare decision-maker. It is therefore paramount that providers both share their knowledge of anal cancer screening to empower their patients and create environments in which patients can safely exercise their agency. HIV positive participants’ experience with chronic disease and their previous engagement with the healthcare system has likely reinforced their belief in knowledge as power. Importantly, our data shows that the uncertainty associated with anal cancer screening can have variable effects on patients’ willingness to rely on provider recommendations and proceed with screening.

This study is limited by a lack of incorporation of other intersectional identities in the analysis, including class and age, which could have profound impacts on the patient-provider relationship and shared decision making. Future studies could include additional intersectional identities, as well as evaluate the implementation of patient and provider shared decision-making tools for anal cancer screening. We would also be interested in assessing how experiences of provider bias vary by the race/ethnicity of the provider.

As providers struggle to find more effective ways of affecting health inequities and disparities within the clinic setting including provider-patient interactions and making their organisations more culturally competent, the realities of how the world outside of the clinic affects health outcomes for patients are driving many to consider the matrix of domination as a public health issue (Gomez and Muntaner 2005). This approach will bring medical doctors out into the communities of their patients and in work that addresses the social, systemic and structural factors within the matrix of domination that contribute to poor health outcomes for their patients (Gomez 2012). More research is needed to develop best practices and possibility models that more providers can use to do this important and necessary work outside of the clinic setting.

Acknowledgments

Would like to thank all the study participants for their time and participation in the anal cancer screening Your Voice! Your Health! sub-study. This study was funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Grant number U18HS023050, Principal Investigator Marshall H. Chin, MD, MPH. Author John Schneider is also funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. Grant number R01MH112406.

Appendix A

Survey questions and response options as administered to study participants.

| I’m generally quite open about being LGBTQ when I visit a healthcare professional. |

| Strongly Agree |

| Agree |

| Neutral |

| Disagree |

| Strongly Disagree |

| Don’t Know/No Experience |

| Does Not Apply to Me |

| In general, I feel respected for who I am as an LGBTQ person by healthcare professionals. |

| Strongly Agree |

| Agree |

| Neutral |

| Disagree |

| Strongly Disagree |

| Don’t Know/No Experience |

| Does Not Apply to Me |

| I actively seek out LGBTQ-friendly healthcare professionals. |

| Strongly Agree |

| Agree |

| Neutral |

| Disagree |

| Strongly Disagree |

| Don’t Know/No Experience |

| Does Not Apply to Me |

| I actively seek out healthcare professionals who match my own race or ethnic origin. |

| Strongly Agree |

| Agree |

| Neutral |

| Disagree |

| Strongly Disagree |

| Don’t Know/No Experience |

| Does Not Apply to Me |

| I have had a visit or consultation with my provider when I discussed tests or treatment and needed to make a decision about my health. |

| Yes |

| No, I never discussed tests or treatment and needed to make a decision about my health |

| My doctor asked me which treatment option I prefer. |

| Completely Disagree |

| Strongly Disagree |

| Somewhat Disagree |

| Somewhat Agree |

| Strongly Agree |

| Completely Agree |

| My doctor and I reached an agreement on how to proceed. |

| Completely Disagree |

| Strongly Disagree |

| Somewhat Disagree |

| Somewhat Agree |

| Strongly Agree |

| Agree |

| Healthcare professionals treated me differently from other patients. |

| This has never happened to me |

| This has happened to me because of homophobia or prejudice against people who are lesbian, gay, or bisexual |

| This has happened to me because of transphobia or prejudice against people who are transgender |

| This has happened to me because of discrimination or prejudice against people living with HIV |

| This has happened to me because of my race or ethnicity |

| This has happened to me, but not for the reasons listed |

| Healthcare professionals blamed me for my health status. |

| This has never happened to me |

| This has happened to me because of homophobia or prejudice against people who are lesbian, gay, or bisexual |

| This has happened to me because of transphobia or prejudice against people who are transgender |

| This has happened to me because of discrimination or prejudice against people living with HIV |

| This has happened to me because of my race or ethnicity |

| This has happened to me, but not for the reasons listed |

Footnotes

Medical apartheid, a term coined by medical writer Harriet A Washington to describe the systemic racial violence of the field of medicine on people of African descent, has deep roots going back to slavery, perpetuated by the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, and persists today related to ongoing healthcare disparities and stigma (Hatzenbuehler 2013; Washington 2006; Brooks 1991; Gamble 1997; Jacobs et al. 2006; Hammond 2010; Guzzo 2012), contributing to medical mistrust.

References

- Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Ghanem KG, Emmanuel P, Zingman BS, and Horberg MA; Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014. “Primary Care Guidelines for the Management of Persons Infected with HIV: 2013 Update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 58 (1): 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashktorab H, Kupfer SS, Brim H, and Carethers JM. 2017. “Racial Disparity in Gastrointestinal Cancer Risk.” Gastroenterology 153 (4): 910–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey AC 2017. The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, and Ananeh-Firempong O. 2003. “Defining Cultural Competence: A Practical Framework for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care.” Public Health Reports 118 (4): 293–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks DD, Smith DR, and Anderson RJ. 1991. “Medical Apartheid: An American Perspective.” The Journal of the American Medical Association 266 (19): 2746–2749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. “HPV-Associated Anal Cancer Rates by Race and Ethnicity.” 2018, August 20 https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/statistics/anal.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. “Preventing HPV-Associated Cancers.” 2018, August 22 https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/basic_info/prevention.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of STD Prevention, Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD and TB Prevention. “HPV-Associated Cancers and Precancers.” 2016, May 23 https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/hpv-cancer.htm.

- Chiao EY, Giordano TP, Palefsky JM, Tyring S, and El Serag H. 2006. “Screening HIV-Infected Individuals for Anal Cancer Precursor Lesions: A Systematic Review.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 43 (2): 223–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree BF, and Miller WL. 1999. “Using Codes and Code Manuals: A Template Organizing Style of Interpretation” InDoing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed., edited by Crabtree BF, Miller WL, 163–177. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza G, Wiley DJ, Li X, Chmiel JS, Margolick JB, Cranston RD, and Jacobson LP. 2008. “Incidence and Epidemiology of Anal Cancer in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 48 (4): 491–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza G, Rajan SD, Bhatia R, Cranston RD, Plankey MW, Silvestre A, Ostrow DG, Wiley D, Shah N, and Brewer NT. 2013. “Uptake and Predictors of Anal Cancer Screening in Men Who Have Sex with Men.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (9): e88–e95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields EL, Bogart LM, Smith KC, Malebranche DJ, Ellen J, and Schuster MA. 2015. ““I Always Felt I Had to Prove My Manhood”: Homosexuality, Masculinity, Gender Role Strain, and HIV Risk Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men.” American Journal of Public Health 105 (1): 122–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields E, Morgan A, Sanders RA. 2016. “The Intersection of Sociocultural Factors and Health-Related Behavior in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: Experiences Among Young Black Gay Males as an Example.” Pediatric Clinics of North America 63 (6): 1091–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamble VN 1997. “Under the Shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care.” American Journal of Public Health 87 (11): 1773–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayman M, and Barragan J. 2013. “Multiple Perceived Reasons for Major Discrimination and Depression.” Society and Mental Health 3 (3): 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MB, Muntaner C. 2005. “Urban Redevelopment and Neighborhood Health in East Baltimore, Maryland: The Role of Communitarian and Institutional Social Capital.” Critical Public Health 15 (2): 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez MB 2012. Race, Class, Power, and Organizing in East Baltimore: Rebuilding Abandoned Communities in America. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA 2012. “Multiple Forms of Perceived Discrimination and Health Among Adolescents and Young Adults.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 53 (2): 199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grollman EA 2014. “Multiple Disadvantaged Statuses and Health: The Role of Multiple Forms of Discrimination.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 55 (1): 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, and Hayford SR. 2012. “Race-Ethnic Differences in Sexual Health Knowledge.” Race and Social Problems 4 (3–4): 158–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP 2010. “Psychosocial Correlates of Medical Mistrust Among African American Men.” American Journal of Community Psychology 45 (1–2): 87–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, and Link BG. 2013. “Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities.” American Journal of Public Health 103 (5): 813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Chopp R, and Strohl D. 2007. “Sexual Stigma: Putting Sexual Minority Health Issues in Context” In The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations, edited by Meyer IH and Northridge ME, 171–208. New York: Springer Science and Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. 2011. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. 2003. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, Whitaker EE, and Warnecke RB. 2006. “Understanding African Americans’ Views of the Trustworthiness of Physicians.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 21 (6): 642–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, and Cooper LA. 2004. “Patient Race/Ethnicity and Quality of Patient–Physician Communication During Medical Visits.” American Journal of Public Health 94 (12): 2084–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KK, Brooks JT, Pau A, and Masur H; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); National Institutes of Health; HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009. “Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Recommendations and Reports 58 (RR-4): 1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz KA, Clarke CA, Bernstein KT, Katz MH, and Klausner JD. 2009. “Is There a Proven Link Between Anal Cancer Screening and Reduced Morbidity or Mortality?” Annals of Internal Medicine 150 (4): 283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz MH, Katz KA, Bernestein KT, and Klausner JD. 2010. “We Need Data on Anal Cancer Screening Effectiveness Before Focusing on Increasing It.” American Journal of Public Health 100 (11): 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeds IL, and Fang SH. 2016. “Anal Cancer and Intraepithelial Neoplasia Screening: A Review.” World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery 8 (1): 41–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limpangog CP 2016. “Matrix of Domination” In: The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 1st ed, edited by Naples N, 1–3. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Margolies L, and Goeren B. 2009. “Anal Cancer, HIV, and Gay/Bisexal Men” In Gay Men’s Health Crisis: Treatment Issues, edited by Schaefer N, 1–2. New York: GMHC, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Cochran SD. 2001. “Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States.” American Journal of Public Health 91 (11): 1869–1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH, Schwartz S, and Frost DM. 2008. “Social Patterning of Stress and Coping: Does Disadvantaged Social Statuses Confer More Stress and Fewer Coping Resources?” Social Science and Medicine 67 (3): 368–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortoski RA, and Kell CS. 2011. “Anal Cancer and Screening Guidelines for Human Papillomavirus in Men.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 111 (3 Suppl 2): S35–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Hanson DL, Sullivan PS, Novak RM, Moorman AC, Tong TC, Holmberg SD, and Brooks JT. 2008. “Incidence of Types of Cancer Among HIV-Infected Persons Compared with the General Population in the United States, 1992–2003.” Annals of Internal Medicine 148 (10): 728–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peek ME, Lopez FY, Williams HS, Xu LJ, McNulty MC, Acree ME, and Schneider JA. 2016. “Development of a Conceptual Framework for Understanding Shared Decision Making Among African-American LGBT Patients and Their Clinicians.” Journal of General Internal Medicine 31 (6): 677–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piketty C, Selinger-Leneman H, Grabar S, Duvivier C, Bonmarchan M, Abramowitz L, Costagliola D, and Mary-Krause M; FHDH-ANRS CO 4. 2008. “Marked Increase in the Incidence of Invasive Anal Cancer Among HIV-Infected Patients Despite Treatment with Combination Antiretroviral Therapy.” AIDS 22 (10): 1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaisime MV, Malebranche DJ, Davis AL, and Taylor JA. 2017. “Healthcare Providers’ Formative Experiences with Race and Black Male Patients in Urban Hospital Environments.” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 4 (6): 1120–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart MA 1995. “Effective Physician-Patient Communication and Health Outcomes: A Review.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 152 (9): 1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong WW, Hillman RJ, Kelleher AD, Grulich AE, and Carr A. 2014. “Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Squamous Cell Carcinoma in HIV-Infected Adults.” HIV Medicine 15 (2): 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zee RP, Richel O, de Vries HJ, and Prins JM. 2013. “The Increasing Incidence of Anal Cancer: Can It Be Explained by Trends in Risk Groups?” The Netherlands Journal of Medicine 71 (8): 401–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh T, Bertozzi-Villa C, and Schneider JA. 2015. “Systematic Review of Racial Disparities in Human Papillomavirus-Associated Anal Dysplasia and Anal Cancer Among Men Who Have Sex with Men.” American Journal of Public Health 105 (4): e34–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington HA 2006. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Wells JS, Holstad MM, Thomas T, and Bruner DW. 2014. “An Integrative Review of Guidelines for Anal Cancer Screening in HIV-Infected Persons.” AIDS Patient Care and STDs 28 (7): 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams HS 2016. “Introduction to Afrocentric Decolonizing Kweer Theory and Epistemology of the Erotic.” Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships 2 (4): 1–31. [Google Scholar]