Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease that is clinically characterized by progressive cognitive decline. More than 200 pathogenic mutations have been identified in amyloid-β precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and presenilin 2 (PSEN2). Additionally, common and rare variants occur within APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 that may be risk factors, protective factors, or benign, non-pathogenic polymorphisms. Yet, to date, no single study has carefully examined the effect of all of the variants of unknown significance reported in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 on Aβ isoform levels in vitro. In this study, we analyzed Aβ isoform levels by ELISA in a cell-based system in which each reported pathogenic and risk variant in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 was expressed individually. In order to classify variants for which limited family history data is available, we have implemented an algorithm for determining pathogenicity using available information from multiple domains, including genetic, bioinformatic, and in vitro analyses. We identified 90 variants of unknown significance and classified 19 as likely pathogenic mutations. We also propose that five variants are possibly protective. In defining a subset of these variants as pathogenic, individuals from these families may eligible to enroll in observational studies and clinical trials.

Keywords: APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, Alzheimer’s disease, Cell-based assays, Pathogenicity algorithm

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized clinically by progressive cognitive decline and neuropathologically by progressive neuronal loss and the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Mutations in amyloid-β precursor protein (APP), presenilin 1 (PSEN1) and presenilin 2 (PSEN2) are the pathogenic cause of autosomal dominant AD (ADAD). Rare recessive mutations in APP (A673V and E693Δ) also cause early onset AD (Di Fede et al., 2009; Giaccone et al., 2010; Tomiyama et al., 2008).

While more than 200 pathogenic mutations have been identified in APP, PSEN1, or PSEN2, more than 90 additional variants have been identified where the pathogenicity remains in question (reviewed in (Karch et al., 2014; Cruts et al., 2012)). The uncertainty in pathogenicity may be due to several reasons. In some cases, variants in APP, PSEN1 or PSEN2 have been identified in families with several generations of AD. In these cases, pathogenicity can be evaluated by segregation analysis: the presence of the variant in multiple individuals with clinically or pathologically confirmed AD and the absence of the variant in healthy, older family members. However, in many cases only the single proband has DNA available. Alternatively, there may be limited or no family history. Challenges also arise when young, healthy individuals are found to be variant carriers. To assess the pathogenicity of novel variants in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 when pedigree and clinical data is limited or incomplete, Guerreiro and colleagues (Guerreiro et al., 2010a) proposed a pathogenicity algorithm. We have since modified and expanded this algorithm to evaluate pathogenicity of six novel variants identified through the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Extended Registry (DIAN-EXR) using genetic, biochemical, biomarker, and clinical data (Hsu et al., 2018). In our modified algorithm, we found that biochemical evidence of a change in Aβ was informative in assessing pathogenicity where genetic data was limited (Hsu et al., 2018).

To date, more than 90 variants of unknown significance are included in genetic databases for Alzheimer’s disease (AD/FTD database and AlzForum Mutations database), in part due to the reliance on genetic information alone for classification of pathogenicity (Cruts et al., 2012). Here, we further modified our pathogenicity algorithm to classify 90 variants of unknown significance for which no family segregation data is available that have been previously reported in the AD/FTD and AlzForum Mutations Databases.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Identification of variants of unknown significance

To identify variants of unknown significance, we queried the AD/FTD ((5)http://www.molgen.ua.ac.be/ADMutations/) and AlzForum Mutations Databases (https://www.alzforum.org/mutations). Variants classified by the Guerreiro et al. algorithm (Guerreiro et al., 2010a) as being “not pathogenic” or “pathogenic nature unclear” were selected for evaluation by bioinformatic and in vitro analyses (n = 90; Supplemental Table 1).

2.2. Bioinformatics

To determine whether APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 variants represented rare or common polymorphisms, we investigated two population-based exome sequencing databases: Exome Variant Server (EVS) and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) browser. The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) was excluded from this study given that sequencing data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project are included in the database and thus would not be representative of a control population. Polymorphism phenotype v2 (PolyPhen-2; (Adzhubei et al., 2010)) and Sorting Intolerant From Tolerant (SIFT) were used to predict whether the amino acid change would be disruptive to the encoded protein.

2.3. In vitro analyses

2.3.1. Plasmids and mutagenesis

The full-length APP cDNA (isoform 695) was cloned into pcDNA3.1 (Wang et al., 2004). APP variants (Table 1) were introduced into the APP cDNA using a QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Clones were sequenced to confirm the presence of the variant and the absence of additional modifications. APP wild-type (WT) and pathogenic APP KM670/671NL, APP L723P and APP K724N mutations were included as controls. Three variants were not generated due to incompatibility with the cDNA plasmid: APP E296K, APP P299L, APP IVS17 83–88delAAGTAT, APP c *18C > T, and APP c *372 A > G (N/A; Table 1).

Table 1.

APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 variants of unknown significance evaluated by the pathogenicity algorithm.

| Variant | ≥5 alleles in EVS/ExAC | Conserved between PSEN1 and PSEN2 | Known pathogenic mutations | Predicted to damage proteina | Increase Aβ42/40 or Aβ42b | Predicted pathogenicityc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APP A201V | Yes | N/A | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP A235V | Yes | N/A | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP D243N | Yes | N/A | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP E246K | No | N/A | No | Possibly damaging | No | Risk factor |

| APP E296K | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| APP P299L | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| APP V340M | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP R468H | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP A479S | Yes | N/A | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP K496Q | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP A500T | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP K510N | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP Y538H | No | N/A | No | Possibly damaging | No | Not pathogenic; Possibly protective |

| APP V562I | No | N/A | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP E599K | Yes | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP T600M | Yes | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP S614G | Yes | N/A | No | Benign | Yes | Risk factor |

| APP P620A | No | N/A | No | Possibly damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| APP P620L | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| APP E665D | No | N/A | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| APP A673T | Yes | N/A | Yes | Benign | No | Not pathogenic; Possibly protective |

| APP H677R | No | N/A | No | Possibly damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| APP G708G | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | Yes | Risk factor |

| APP G709S | Yes | N/A | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| APP A713T | Yes | N/A | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Risk factor |

| APP A713V | Yes | N/A | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic; Possibly protective |

| APP H733P | No | N/A | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| APP IVS17 83–88delAAGTAT | No | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Unknown |

| APP c *18C > T | No | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Unknown |

| APP c *372 A > G | No | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | Unknown |

| PSEN1 N32N | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 R35Q | Yes | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 D40del | Yes | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | Risk factor |

| PSEN1 E69D | No | No | No | Benign | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 M84V | No | Yes | Yes | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 T99A | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 R108Q | No | No | No | Benign | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 QR127G | No | Yes | No | N/A | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 H131R | No | No | No | Benign | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 M146V | No | Yes | Yes | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 H163P | No | Yes | Yes | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN1 I168T | No | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 F175S | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 F176L | No | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 V191A | No | Yes | No | Possibly damaging | No | Not pathogenic; Possibly protective |

| PSEN1 L219R | No | Yes | Yes | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN1 E318G | Yes | Yes | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 D333G | Yes | No | No | Possibly damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 R352C | Yes | No | No | Possibly damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN1 InsR352 | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | Unknown |

| PSEN1 T354I | No | No | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN1 R358Q | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 S365Y | No | No | No | Possibly damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN1 G378fs | No | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 A396T | No | No | Yes | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN1 I439V | No | Yes | Yes | Benign | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN2 T18M | Yes | No | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 R29H | No | No | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Probable pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 G34S | Yes | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 R62C | Yes | Yes | No | Possibly damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 R62H | Yes | Yes | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 P69A | Yes | Yes | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 R71W | Yes | Yes | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 K82R | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | No | Risk factor |

| PSEN2 A85V | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | No | Risk factor |

| PSEN2 V101M | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 P123L | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN2 E126fs | No | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | Risk factor |

| PSEN2 S130L | Yes | No | No | Possibly damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 V139M | Yes | No | No | Possibly damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 L143H | No | No | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 R163H | No | No | No | Probably damaging | No | Not Pathogenic |

| PSEN2 H162N | Yes | No | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 M174V | No | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 V214L | Yes | Yes | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 I235F | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN2 A237V | Yes | Yes | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 L238F | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN2 A252T | Yes | Yes | No | Possibly damaging | No | Not pathogenic; Possibly protective |

| PSEN2 A258V | No | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 R284G | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN2 T301M | Yes | No | No | Possibly damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic; Risk factor |

| PSEN2 K306fs | No | No | No | N/A | N/A | Unknown |

| PSEN2 P334A | No | No | No | Benign | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 P334R | Yes | No | No | Benign | N/A | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 P348L | No | No | No | Benign | Yes | Probable pathogenic |

| PSEN2 A377V | Yes | Yes | No | Probably damaging | N/A | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 V393M | Yes | Yes | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 T421M | No | Yes | No | Probably damaging | No | Not pathogenic |

| PSEN2 D439A | Yes | Yes | No | Probably damaging | Yes | Risk factor |

Benign, assigned by PolyPhen to mean not damaging.

N/A, cell-based data not available (see Materials and Methods).

Unknown indicates there is not sufficient functional/bioinformatic evidence to assign pathogenicity. Two assignments are made when functional/bioinformatics data is not complete.

The full-length PSEN1 cDNA was cloned into pcDNA3.1 myc/his vector (Brunkan et al., 2005). PSEN1 variants (Table 1) were introduced into the PSEN1 cDNA and screened as described above. PSEN1 WT and pathogenic PSEN1 A79V, PSEN1 L286V, and PSEN1 exon 9 deletion (ΔE9) mutations were included as controls. One variant was not generated due to incompatibility with the cDNA plasmid: PSEN1 N32N. Four additional variants failed at the mutagenesis step and were not modeled in the cellular assay: PSEN1 L219R, PSEN1 D333G, PSEN1 T354I, and PSEN1 S365Y (N/A; Table 1).

The full-length PSEN2 cDNA was cloned into pcDNA3.1 vector (Kovacs et al., 1996). PSEN2 variants (Table 1) were introduced into the PSEN2 cDNA and screened as described above. PSEN2 WT and the pathogenic PSEN2 N141I mutation were included as controls (Walker et al., 2005). Nine variants failed at the mutagenesis step and were not modeled in the cellular assay: PSEN2 T18M, PSEN2 R29H, PSEN2 V101M, PSEN2 S130L, PSEN2 H162N, PSEN1 V214L, PSEN2 T301M, PSEN2 K306fs, and PSEN2 P334R (N/A; Table 1).

In total, we generated 65 plasmids containing variants of unknown significance in APP, PSEN1 or PSEN2.

2.3.2. Transient transfection

To assess APP variants, we transiently expressed APP WT, variant, or mutant APP in mouse neuroblastoma cells (N2A). To assess PSEN1 and PSEN2 variants, we used mouse neuroblastoma cells in which endogenous Psen1 and Psen2 were knocked out by CRISPR/Cas9 (N2A-PS1/PS2 KO; Pimenova and Goate, 2020). We then transiently expressed human APP WT (695 isoform) along with the PSEN1 or PSEN2 constructs. N2A cells were maintained in equal amounts of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium and Opti-MEM, supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 100 μg/mL penicillin/streptomycin. Upon reaching confluency, cells were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Culture media was replaced after 24 h, and cells were incubated for another 24 h prior to analysis of extracellular Aβ in the media. Three independent transfections were performed for each construct and used for subsequent analyses. Six variants exhibited low expression levels when transiently expressed and thus were not included in the Aβ ELISA analyses: APP H677R, APP G709S, PSEN1 H163P, PSEN2 L143H, PSEN2 A237V and PSEN2 A377V (N/A; Table 1).

2.3.3. Aβ Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Conditioned media was collected and centrifuged at 3000 ×g at 4 °C for 10 min to remove cell debris. Levels of Aβ40 and Aβ42 in cell culture media were measured by sandwich ELISA as directed by the manufacturer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Statistical difference was measured using a one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Dunnett test.

2.3.4. Immunoblotting

Cell pellets were extracted on ice in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.6, 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP40, 0.5% Triton 100×, protease inhibitor cocktail) and centrifuged at 14,000 ×g. Protein concentration was measured by BCA method as described by the manufacturer (Pierce-Thermo). Standard SDS-PAGE was performed in 4–20% Criterion TGX gels (Bio-Rad). Samples were boiled for 5 min in Laemmli sample buffer prior to electrophoresis (Laemmli, 1970). Immunoblots were probed with 22C11 (1:1000; Millipore) and goat-anti-rabbit-HRP (1:5000; Thermo Fisher).

3. Results and discussion

3.1. The impact of variants of unknown significance in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 on Aβ levels in vitro

Prior cellular studies have largely focused on defining the impact of known pathogenic mutations in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 on extracellular Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (Haass et al., 1994; Haass et al., 1995; Sun et al., 2017). Many common and rare variants occur within APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 that may be risk factors, protective factors, or benign, non-pathogenic polymorphisms (Cruchaga et al., 2012; Sassi et al., 2014). Yet, to date, no single study has systematically examined the impact of these variants of unknown significance on Aβ isoform levels in vitro. The goal of this study was to determine the extent to which variants in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 impact Aβ isoform levels and to determine the utility of our assay to discriminate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic variants.

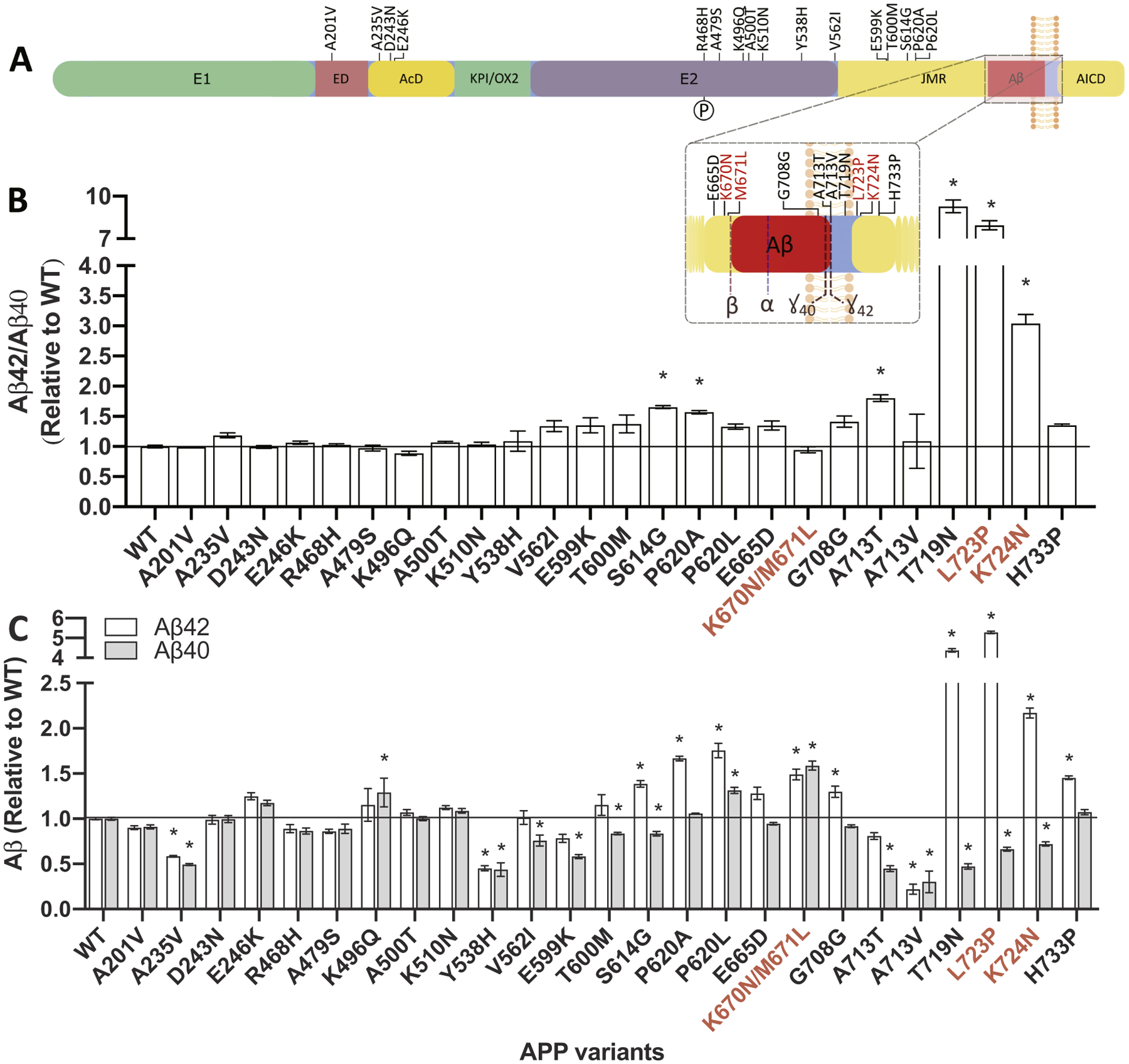

We compared extracellular Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ42/40 in the media of mouse N2A cells expressing APP WT, pathogenic APP mutations (KM670/671NL, L723P or K724N) or APP containing one of 22 variants of unknown significance (Fig. 1). We found that four of the 22 APP variants resulted in a significant increase in the Aβ42/40 ratio compared with APP WT: APP S614G, APP P620A, APP A713T, and APP T719N (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table 2). APP T719N was a variant of unknown significance that has recently been classified as pathogenic (Hsu et al., 2018). Consistent with the reported effects of APP KM670/671NL, we found that one APP variant (APP P620L) produced a significant increase in Aβ40 and Aβ42 without altering the Aβ42/40 ratio (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Table 2). Two APP variants resulted in a significant increase in Aβ42 without significantly altering the Aβ42/40 ratio: APP G708G and APP H733P (Fig. 1; Supplemental Table 2). Those variants that significantly increased the Aβ42/40 ratio or Aβ40 and Aβ42 occur in the juxtamembrane region or amyloid beta domain consistent with known pathogenic mutations; however, some variants, including APP S614G, APP P620L, and APP P620A, occur outside of the regions that are routinely sequenced (Fig. 1A) (Cruts et al., 2012).

Fig. 1. Impact of APP variants of unknown significance on Aβ levels in vitro.

A. Diagram of the location of variants of unknown significance in APP. B-C. Mouse N2A cells were transiently transfected with plasmids containing APP695 WT, known pathogenic mutations (K670N/M671L, L723P, K724N), or a variant of unknown significance. After 48 h, media was collected and analyzed for Aβ42 and Aβ40 by ELISA. B. Ratio of Aβ42/40 expressed relative to APP WT. C. Aβ42 (white box) and Aβ40 (gray box) levels expressed relative to APP WT. Graphs represent mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Significance indicated by Dunnett’s t-test (*, p < .05). Red, known pathogenic mutations. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

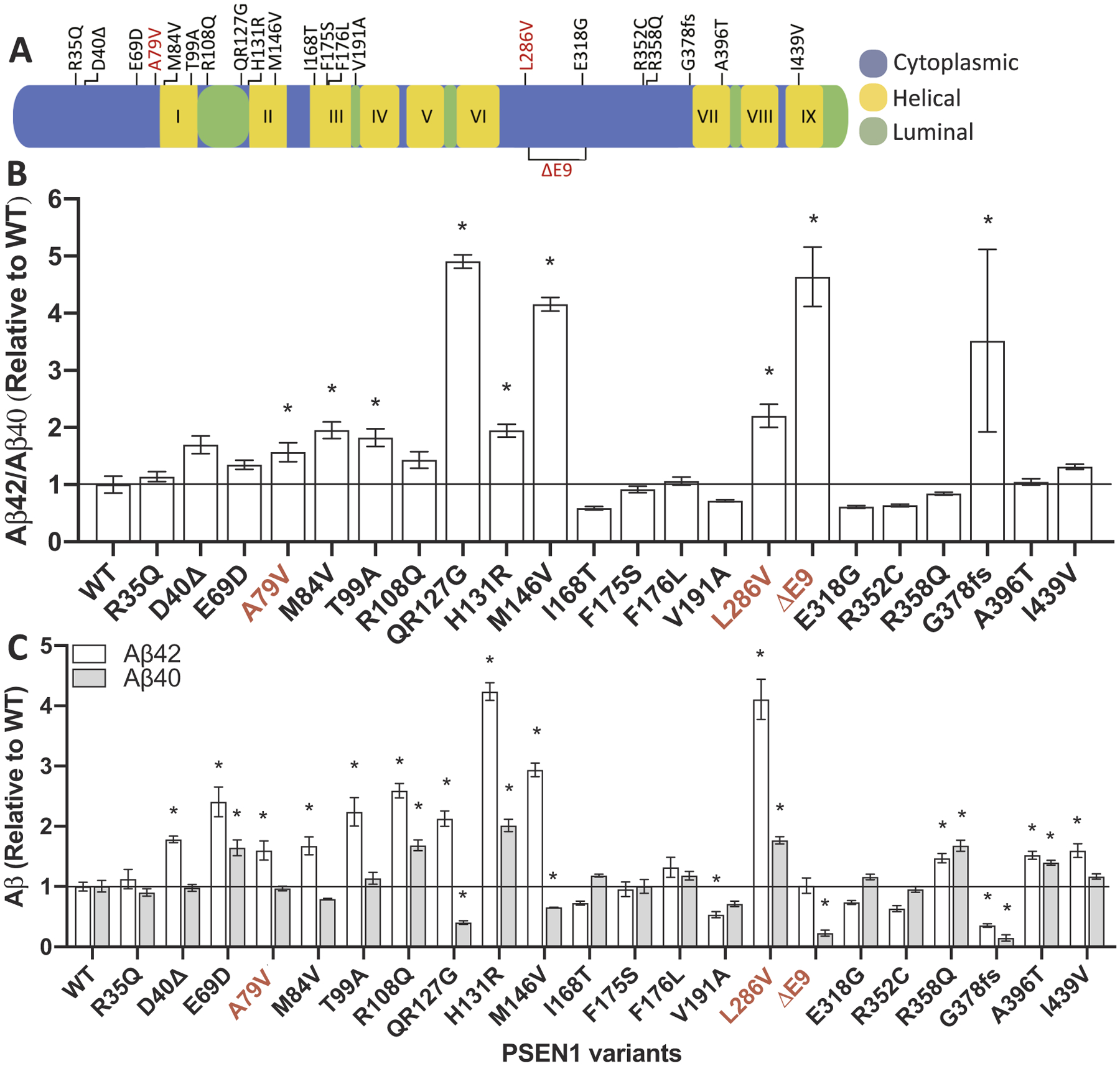

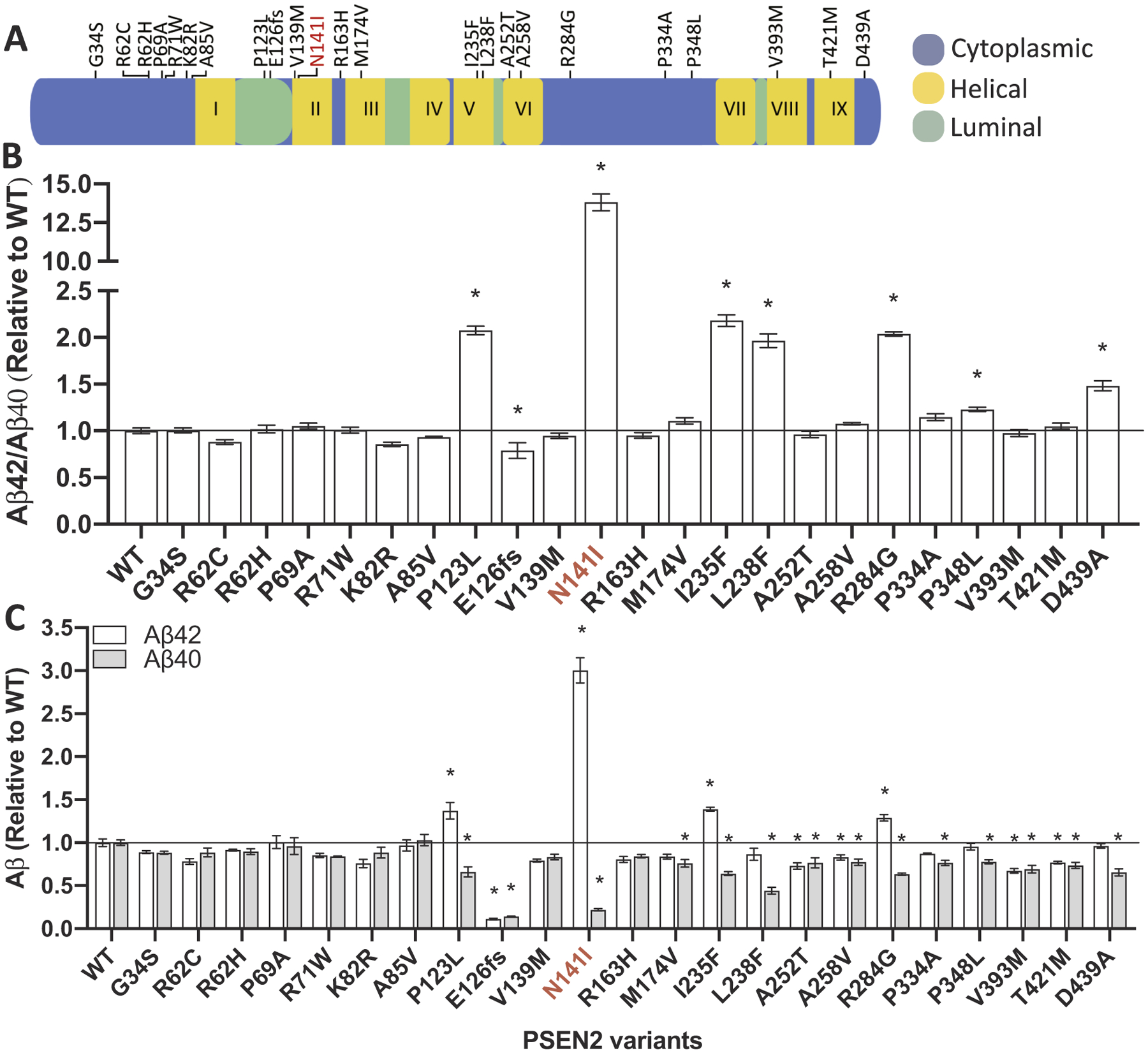

To evaluate variants of unknown significance in PSEN1 and PSEN2, we selected a cell line in which APP is metabolized similarly to neuronal cells and in which endogenous presenilin genes are absent in order to avoid background Aβ production: N2A-PS1/PS2 KO. The absence of endogenous Psen1 and Psen2 allows us to capture effects of known pathogenic mutations in these genes, where a robust reduction in Aβ40 results in a shift in the Aβ42/40 ratio. We evaluated 19 variants in PSEN1 and 22 variants in PSEN2 (Figs. 2 and 3). Aβ40, Aβ42, and Aβ42/40 levels were compared to PSEN1 WT or PSEN2 WT, respectively. Six of the 19 PSEN1 variants resulted in a significant increase in the Aβ42/40 ratio: PSEN1 M84V, PSEN1 T99A, PSEN1 QR127G, PSEN1 H131R, PSEN1 M146V, and PSEN1 G378fs (Fig. 2; Supplemental Table 2). Six variants resulted in a significant increase in Aβ40 and Aβ42 or Aβ42 only compared with PSEN1 WT: PSEN1 D40Δ, PSEN1 E69D, PSEN1 R108Q, PSEN1 R358Q, PSEN1 A396T, and PSEN1 I439V (Fig. 2; Supplemental Table 2). We found that six of 22 PSEN2 variants resulted in a significant increase in the Aβ42/40 ratio: PSEN2 P123L, PSEN2 I235F, PSEN2 L238F, PSEN2 R284G, PSEN2 P348L, and PSEN2 D439A (Fig. 3; Supplemental Table 2). We evaluated several known polymorphisms in PSEN2 that do not cause AD: PSEN2 R62H and PSEN2 R71W (Walker et al., 2005). Cells expressing these benign variants failed to produce a significant change in Aβ40 or Aβ42 (Fig. 3). Overall, variants of unknown significance in PSEN1 and PSEN2 that alter Aβ were located across the gene. Thus, leveraging multiple types of data (genetic, bioinformatic, and cellular) are most informative in evaluating variants of unknown significance.

Fig. 2. Impact of PSEN1 variants of unknown significance on Aβ levels in vitro.

A. Diagram of the location of variants of unknown significance in PSEN1. B-C. Mouse N2A-PS1/PS2 KO cells were transiently transfected with plasmids containing APP WT and PSEN1 WT, known pathogenic mutations (A79V, L286V, and ΔE9), or a variant of unknown significance. After 48 h, media was collected and analyzed for Aβ42 and Aβ40 by ELISA. B. Ratio of Aβ42/40 expressed relative to PSEN1 WT. C. Aβ42 (white box) and Aβ40 (gray box) levels expressed relative to PSEN1 WT. Graphs represent mean ± SEM. Significance indicated by Dunnett’s t-test (*, p < .05). Red, known pathogenic mutations. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 3. Impact of PSEN2 variants of unknown significance on Aβ levels in vitro.

A. Diagram of the location of variants of unknown significance in PSEN2. B-C. Mouse N2A-PS1/PS2 KO cells were transiently transfected with plasmids containing APP WT and PSEN2 WT, known pathogenic mutations (N141I), or a variant of unknown significance. After 48 h, media was collected and analyzed for Aβ42 and Aβ40 by ELISA. B. Ratio of Aβ42/40 expressed relative to PSEN2 WT. C. Aβ42 (white box) and Aβ40 (gray box) levels expressed relative to PSEN2 WT. Graphs represent mean ± SEM. Significance indicated by Dunnett’s t-test (*, p < .05). Red, known pathogenic mutations. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

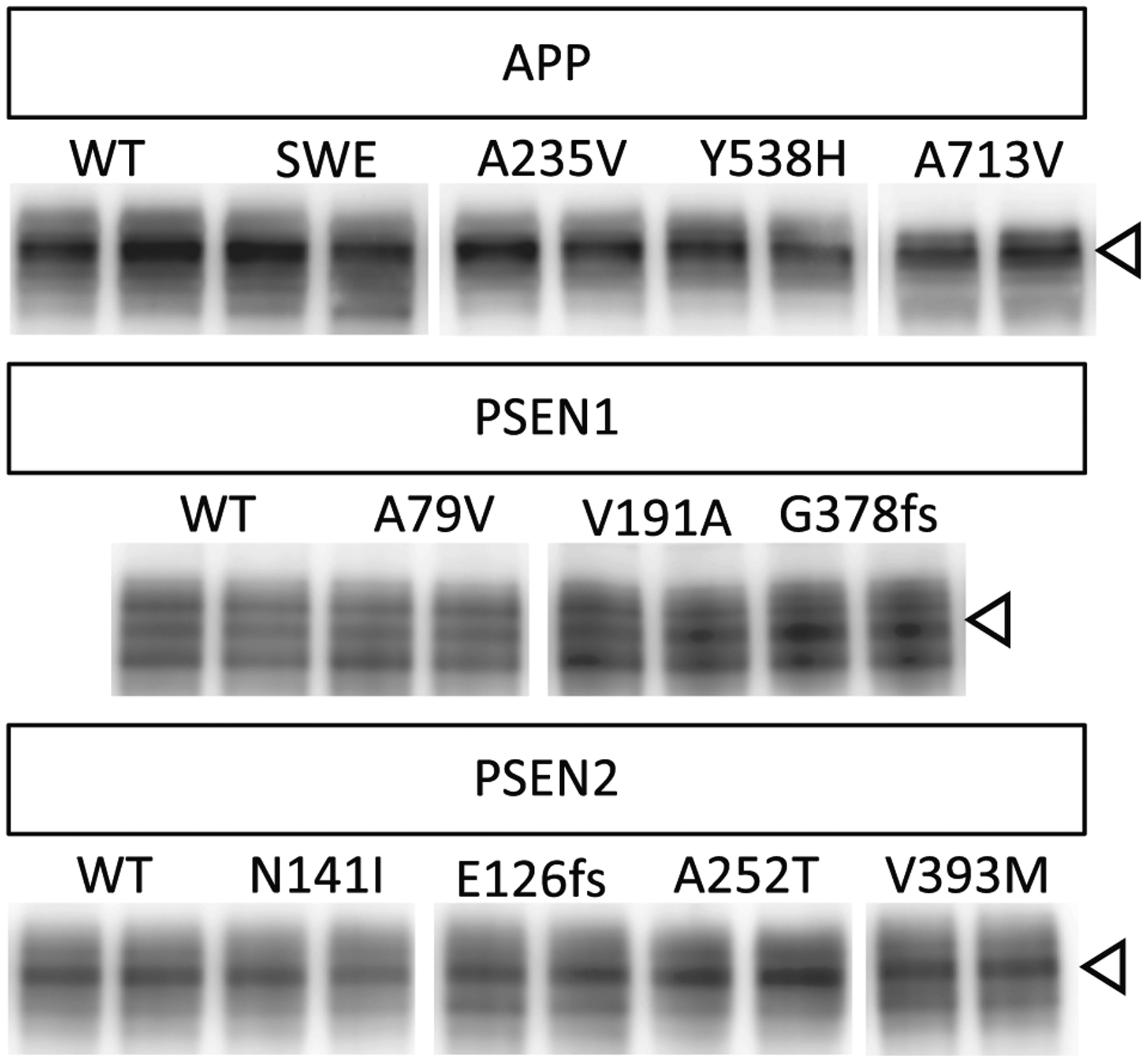

While the pathogenicity algorithm is designed to discriminate between pathogenic and non-pathogenic variants, by utilizing the in vitro assay, we have the opportunity to discriminate between benign, non-pathogenic variants and those that may confer resilience to AD. A rare variant in APP, APP A673T, has been reported to confer protection against AD risk (Jonsson et al., 2012; Maloney et al., 2014). In vitro, APP A673T results in a significant reduction of Aβ42 and Aβ40 without altering total APP levels by decreasing BACE activity (Maloney et al.,2014). Interestingly, we observed that eight variants in APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 produced significantly lower levels of Aβ42 and Aβ40 (Figs. 1–3; Supplemental Table 2) without altering total APP levels: APP A235V; APP Y538H; APP V713V; PSEN1 V191A; PSEN1 G378fs; PSEN2 E126fs; PSEN2 A252T; PSEN2 V393M (Fig. 4). Thus, we propose that these variants may reduce Aβ production and confer resilience to AD.

Fig. 4. APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 variants that reduce Aβ do not alter total APP levels.

Cells transiently overexpressing WT and risk variants for 48 h were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as described in Methods. Immunoblots were probed with 22C11 (full-length APP; open arrow). The immunoblot is representative of 3 replicate experiments.

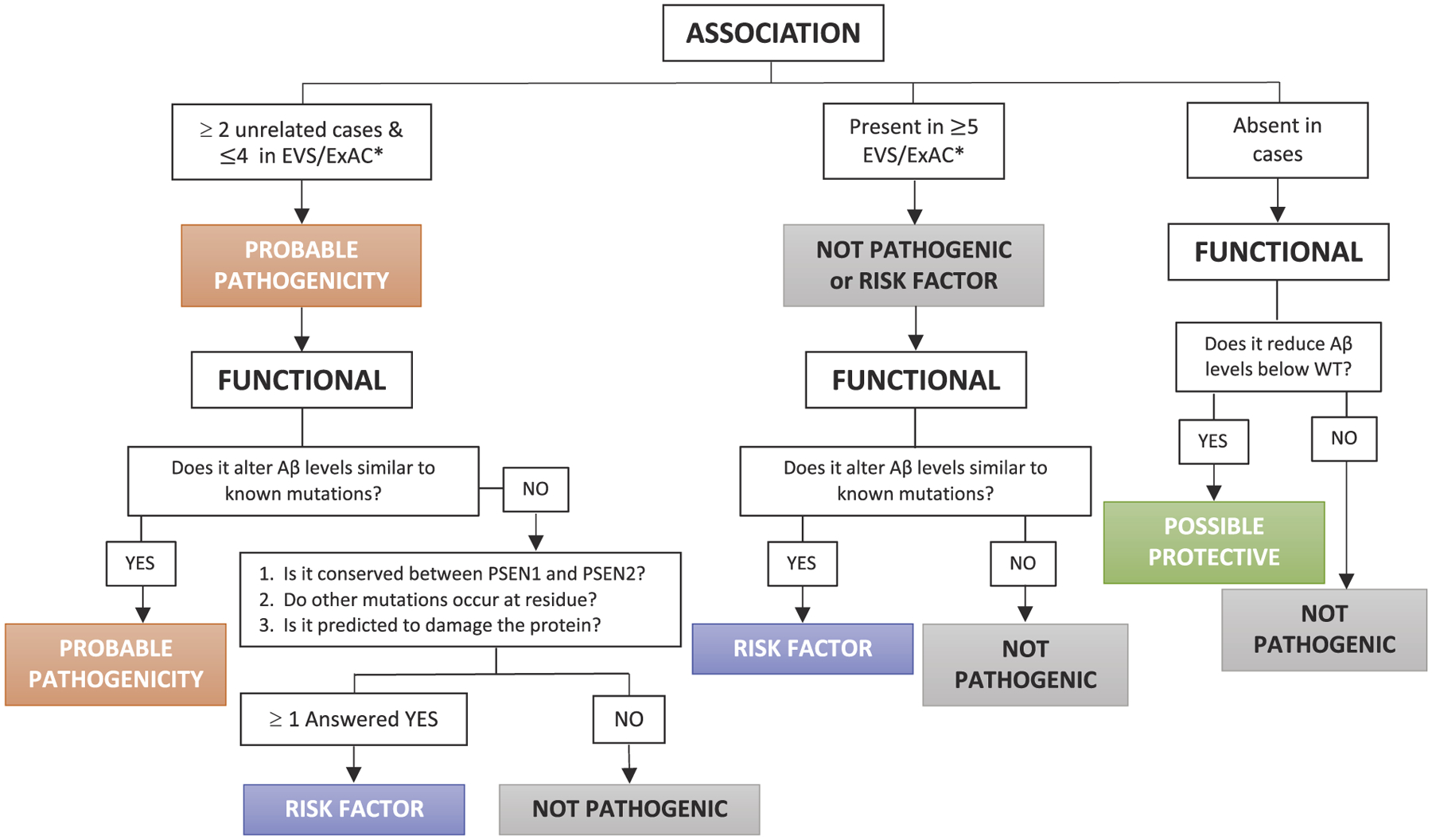

3.2. Pathogenicity

Evaluating pathogenicity of variants of unknown significance requires carefully weighing the clinical phenotype of the variant carrier along with bioinformatic predictions and functional analyses. By evaluating more than 90 variants of unknown significance in vitro, we found that only a subset of variants were able to significantly alter Aβ40, Aβ42, or Aβ42/40 in a manner consistent with known pathogenic mutations. Thus, we propose that the impact of variants on extracellular Aβ levels in vitro should be weighed separately in the pathogenicity algorithm. As such, we have revised the pathogenicity algorithm for use when segregation data is unavailable (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Algorithm to classify variants of unknown significance in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 when family segregation data is not available.

This model is modified from the algorithm previously proposed by Guerreiro et al 2010 and Hsu et al., 2018 (Guerreiro et al., 2010a; Hsu et al., 2018) to focus on variants of unknown significance for which no family segregation data is available. *EVS/ExAC databases should be used to evaluate the presence of a novel variant in the population. GnomAD contains data from the Alzheimer’s Disease Sequencing Project and thus may be enriched for variants that contribute to AD risk.

Applying this modified pathogenicity algorithm to the 90 variants of unknown significance, we classified 19 variants as probably pathogenic (APP P620A; APP P620L; APP H733P; PSEN1 E69D; PSEN1 M84V; PSEN1 T99A; PSEN1 R108Q; PSEN1 QR127G; PSEN1 H131R; PSEN1 M146V; PSEN1 R358Q; PSEN1 G378fs; PSEN1 A396T; PSEN1 I439V; PSEN2 P123L; PSEN2 I235F; PSEN2 L238F; PSEN2 R284G; PSEN2 P348L; Table 1). Many of the variants of unknown significance were identified in single individuals presenting clinically with AD (Guerreiro et al., 2010a; Hsu et al., 2018; Sassi et al., 2014; Nicolas et al., 2016; Guerreiro et al., 2010b; Ikeda et al., 2013; Dobricic et al., 2012; Rogaeva et al., 2001; Lohmann et al., 2012; Blauwendraat et al., 2016). Our in vitro assay revealed that nine variants significantly reduced Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels (Figs. 1C, 2C, 3C). Among these variants, four variants were identified in individuals with AD (Supplemental Table 1), while five variants were identified in individuals with no evidence of neurodegeneration (APP Y538H, APP A673T, APP A713V, PSEN1 V191A, PSEN2 A252T; Table 1). Thus, we predict that these five variants confer resilience to AD.

4. Conclusions

Here, we applied genetic, bioinformatic, and functional data to an algorithm to assess pathogenicity of variants of unknown significance in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2. We propose that 19 variants are probable pathogenic AD mutations. This algorithm was adapted and modified from a pathogenicity algorithm originally proposed by Guerreiro and colleagues (Guerreiro et al., 2010a) to impute pathogenicity when extensive genetic data is missing. We have expanded upon this algorithm in several important ways: (1) expanding the number of controls in the association analyses from 100 to 65,000 by leveraging the EVS and ExAC databases; (2) incorporating cell-based assays to evaluate the impact of novel variants on Aβ levels; and (3) evaluating the bioinformatic functional findings (e.g. conservation between PSEN1 and PSEN2 and the presence of other mutations at the same residue) independent of the cell-based functional findings. The cell-based assay focused on the impact of variants on Aβ42 and Aβ40 levels. Some pathogenic mutations have been reported to lead to reduced Aβ40 and elevated Aβ43 and Aβ42 (Chavez-Gutierrez et al., 2012). In many of these mutations, the increase in Aβ43 is much greater than Aβ42 (Chavez-Gutierrez et al., 2012). Because our assays focus on Aβ42 and Aβ40, we may not capture the magnitude of the aberrant effect on Aβ levels. Ultimately, definitive pathogenicity comes from segregation: presence of the variant in multiple family members with autopsy confirmed AD and absence in family members free of disease. Designation of a variant as pathogenic will allow for individuals to enroll in observational studies and clinical trials for AD, with clear applications in clinical and research settings.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104817.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Carlos Cruchaga for thoughtful discussion of the manuscript. Funding provided by the NIH: U01AG052411 and Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN, UF1AG032438) and the Washington University-Centene Corporation Personalized Medicine Initiative.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

AMG is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board for Denali Therapeutics and on the Genetic Scientific Advisory Panel for Pfizer. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR, 2010. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods 7, 248–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauwendraat C, Wilke C, Jansen IE, Schulte C, Simon-Sanchez J, Metzger FG, Bender B, Gasser T, Maetzler W, Rizzu P, Heutink P, Synofzik M, 2016. Pilot whole-exome sequencing of a German early-onset Alzheimer’s disease cohort reveals a substantial frequency of PSEN2 variants. Neurobiol Aging 37 (208 e211–208 e217). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunkan AL, Martinez M, Walker ES, Goate AM, 2005. Presenilin endoproteolysis is an intramolecular cleavage. Mol. Cell. Neurosci 29, 65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez-Gutierrez L, Bammens L, Benilova I, Vandersteen A, Benurwar M, Borgers M, Lismont S, Zhou L, Van Cleynenbreugel S, Esselmann H, Wiltfang J, Serneels L, Karran E, Gijsen H, Schymkowitz J, Rousseau F, Broersen K, De Strooper B, 2012. The mechanism of gamma-secretase dysfunction in familial Alzheimer disease. EMBO J. 31, 2261–2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruchaga C, Haller G, Chakraverty S, Mayo K, Vallania FL, Mitra RD, Faber K, Williamson J, Bird T, Diaz-Arrastia R, Foroud TM, Boeve BF, Graff-Radford NR, St Jean P, Lawson M, Ehm MG, Mayeux R, Goate AM, 2012. Rare variants in APP, PSEN1 and PSEN2 increase risk for AD in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease families. PLoS One 7, e31039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruts M, Theuns J, Van Broeckhoven C, 2012. Locus-specific mutation databases for neurodegenerative brain diseases. Hum. Mutat 33, 1340–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Fede G, Catania M, Morbin M, Rossi G, Suardi S, Mazzoleni G, Merlin M, Giovagnoli AR, Prioni S, Erbetta A, Falcone C, Gobbi M, Colombo L, Bastone A, Beeg M, Manzoni C, Francescucci B, Spagnoli A, Cantu L, Del Favero E, Levy E, Salmona M, Tagliavini F, 2009. A recessive mutation in the APP gene with dominant-negative effect on amyloidogenesis. Science 323, 1473–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobricic V, Stefanova E, Jankovic M, Gurunlian N, Novakovic I, Hardy J, Kostic V, Guerreiro R, 2012. Genetic testing in familial and young-onset Alzheimer’s disease: mutation spectrum in a Serbian cohort. Neurobiol. Aging 33 (1481) (e1487–1412). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaccone G, Morbin M, Moda F, Botta M, Mazzoleni G, Uggetti A, Catania M, Moro ML, Redaelli V, Spagnoli A, Rossi RS, Salmona M, Di Fede G, Tagliavini F, 2010. Neuropathology of the recessive A673V APP mutation: Alzheimer disease with distinctive features. Acta Neuropathol. 120, 803–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro RJ, Baquero M, Blesa R, Boada M, Brás JM, Bullido MJ, Calado A, Crook R, Ferreira C, Frank A, Gómez-Isla T, Hernández I, Lleó A, Machado A, Martínez-Lage P, Masdeu J, Molina-Porcel L, Molinuevo JL, Pastor P, Pérez-Tur J, Relvas R, Oliveira CR, Ribeiro MH, Rogaeva E, Sa A, Samaranch L, Sánchez-Valle R, Santana I, Tàrraga L, Valdivieso F, Singleton A, Hardy J, Clarimón J, 2010a. Genetic screening of Alzheimer’s disease genes in Iberian and African samples yields novel mutations in presenilins and APP. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro RJ, Baquero M, Blesa R, Boada M, Bras JM, Bullido MJ, Calado A, Crook R, Ferreira C, Frank A, Gomez-Isla T, Hernandez I, Lleo A, Machado A, Martinez-Lage P, Masdeu J, Molina-Porcel L, Molinuevo JL, Pastor P, Perez-Tur J, Relvas R, Oliveira CR, Ribeiro MH, Rogaeva E, Sa A, Samaranch L, Sanchez-Valle R, Santana I, Tarraga L, Valdivieso F, Singleton A, Hardy J, Clarimon J, 2010b. Genetic screening of Alzheimer’s disease genes in Iberian and African samples yields novel mutations in presenilins and APP. Neurobiol. Aging 31, 725–731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Hung AY, Selkoe DJ, Teplow DB, 1994. Mutations associated with a locus for familial Alzheimer’s disease result in alternative processing of amyloid beta-protein precursor. J. Biol. Chem 269, 17741–17748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, Lemere CA, Capell A, Citron M, Seubert P, Schenk D, Lannfelt L, Selkoe DJ, 1995. The Swedish mutation causes early-onset Alzheimer’s disease by beta-secretase cleavage within the secretory pathway. Nat. Med 1, 1291–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S, Gordon BA, Hornbeck R, Norton JB, Levitch D, Louden A, Ziegemeier E, Laforce R Jr., Chhatwal J, Day GS, McDade E, Morris JC, Fagan AM, Benzinger TLS, Goate AM, Cruchaga C, Bateman RJ, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer N., Karch CM, 2018. Discovery and validation of autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease mutations. Alzheimers Res. Ther 10, 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Yonemura K, Kakuda S, Tashiro Y, Fujita Y, Takai E, Hashimoto Y, Makioka K, Furuta N, Ishiguro K, Maruki R, Yoshida J, Miyaguchi O, Tsukie T, Kuwano R, Yamazaki T, Yamaguchi H, Amari M, Takatama M, Harigaya Y, Okamoto K, 2013. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of phosphorylated tau and Abeta1–38/Abeta1–40/Abeta1–42 in Alzheimer’s disease with PS1 mutations. Amyloid 20, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson T, Atwal JK, Steinberg S, Snaedal J, Jonsson PV, Bjornsson S, Stefansson H, Sulem P, Gudbjartsson D, Maloney J, Hoyte K, Gustafson A, Liu Y, Lu Y, Bhangale T, Graham RR, Huttenlocher J, Bjornsdottir G, Andreassen OA, Jonsson EG, Palotie A, Behrens TW, Magnusson OT, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Watts RJ, Stefansson K, 2012. A mutation in APP protects against Alzheimer’s disease and age-related cognitive decline. Nature 488, 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karch CM, Cruchaga C, Goate AM, 2014. Alzheimer’s disease genetics: from the bench to the clinic. Neuron 83, 11–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs DM, Fausett HJ, Page KJ, Kim TW, Moir RD, Merriam DE, Hollister RD, Hallmark OG, Mancini R, Felsenstein KM, Hyman BT, Tanzi RE, Wasco W, 1996. Alzheimer-associated presenilins 1 and 2: neuronal expression in brain and localization to intracellular membranes in mammalian cells. Nat. Med 2, 224–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK, 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann E, Guerreiro RJ, Erginel-Unaltuna N, Gurunlian N, Bilgic B, Gurvit H, Hanagasi HA, Luu N, Emre M, Singleton A, 2012. Identification of PSEN1 and PSEN2 gene mutations and variants in Turkish dementia patients. Neurobiol. Aging 33 (1850), e1817–e1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney JA, Bainbridge T, Gustafson A, Zhang S, Kyauk R, Steiner P, van der Brug M, Liu Y, Ernst JA, Watts RJ, Atwal JK, 2014. Molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease protection by the A673T allele of amyloid precursor protein. J. Biol. Chem 289 (45), 30990–31000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas G, Wallon D, Charbonnier C, Quenez O, Rousseau S, Richard AC, Rovelet-Lecrux A, Coutant S, Le Guennec K, Bacq D, Garnier JG, Olaso R, Boland A, Meyer V, Deleuze JF, Munter HM, Bourque G, Auld D, Montpetit A, Lathrop M, Guyant-Marechal L, Martinaud O, Pariente J, Rollin-Sillaire A, Pasquier F, Le Ber I, Sarazin M, Croisile B, Boutoleau-Bretonniere C, Thomas-Anterion C, Paquet C, Sauvee M, Moreaud O, Gabelle A, Sellal F, Ceccaldi M, Chamard L, Blanc F, Frebourg T, Campion D, Hannequin D, 2016. Screening of dementia genes by whole-exome sequencing in early-onset Alzheimer disease: input and lessons. Eur. J. Hum. Genet 24, 710–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimenova AA, Goate AM, 2020. February 4. Novel presenilin 1 and 2 double knock-out cell line for in vitro validation of PSEN1 and PSEN2 mutations. Neurobiol Dis. 138, 104785. 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaeva EA, Fafel KC, Song YQ, Medeiros H, Sato C, Liang Y, Richard E, Rogaev EI, Frommelt P, Sadovnick AD, Meschino W, Rockwood K, Boss MA, Mayeux R, St George-Hyslop P, 2001. Screening for PS1 mutations in a referral-based series of AD cases: 21 novel mutations. Neurology 57, 621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassi C, Guerreiro R, Gibbs R, Ding J, Lupton MK, Troakes C, Al-Sarraj S, Niblock M, Gallo JM, Adnan J, Killick R, Brown KS, Medway C, Lord J, Turton J, Bras J, Alzheimer’s Research UKC, Morgan K, Powell JF, Singleton A, Hardy J, 2014. Investigating the role of rare coding variability in Mendelian dementia genes (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, GRN, MAPT, and PRNP) in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 35 (2881 e2881–2881 e2886). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhou R, Yang G, Shi Y, 2017. Analysis of 138 pathogenic mutations in presenilin-1 on the in vitro production of Abeta42 and Abeta40 peptides by gamma-secretase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 114, E476–E485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama T, Nagata T, Shimada H, Teraoka R, Fukushima A, Kanemitsu H, Takuma H, Kuwano R, Imagawa M, Ataka S, Wada Y, Yoshioka E, Nishizaki T, Watanabe Y, Mori H, 2008. A new amyloid beta variant favoring oligomerization in Alzheimer’s-type dementia. Ann. Neurol 63, 377–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker ES, Martinez M, Brunkan AL, Goate A, 2005. Presenilin 2 familial Alzheimer’s disease mutations result in partial loss of function and dramatic changes in Abeta 42/40 ratios. J. Neurochem 92, 294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Brunkan AL, Hecimovic S, Walker E, Goate A, 2004. Conserved “PAL” sequence in presenilins is essential for gamma-secretase activity, but not required for formation or stabilization of gamma-secretase complexes. Neurobiol. Dis 15, 654–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.