Abstract

We report the synthesis of unsaturated silacycles via an intramolecular silyl-Heck reaction. Using palladium catalysis, silicon electrophiles tethered to alkenes cyclize to form 5- and 6-membered silicon heterocycles. The effects of alkene substitution and tether length on the efficiency and regioselectivity of the cyclizations are described. Finally, through the use of an intramolecular tether, the first examples of disubstituted alkenes in silyl-Heck reactions are reported.

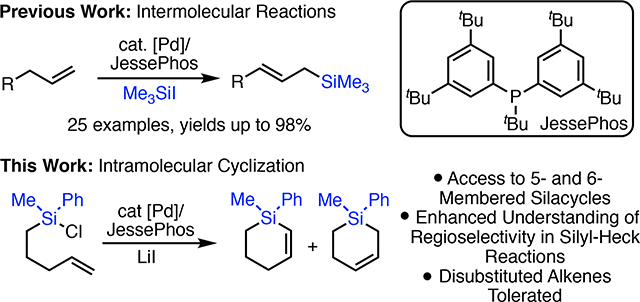

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several years our lab has developed a general and mild protocol for the direct synthesis of allyl and vinyl silanes directly from unfunctionalized terminal alkenes via the silyl-Heck reaction.1 Our main studies have focused on palladium-catalyzed reactions, which allow for highly regiospecific terminal silylation of alkenes with good to excellent levels of isomeric and geometric control of the double bond in the product. Moreover, we recently developed a second-generation ligand for these reactions, which allows for lower reaction temperatures, better yields, and greater product selectivity (Scheme 1, top).1e In 2014, we also reported nickel-catalyzed conditions that allow for the preparation of vinyl silanes.1d These methods provide a straightforward means of preparing unsaturated silanes. Most recently, Shimada and Nakajima have also shown similar reactions using chlorosilanes with Lewis acid promotors.2,3

Scheme 1.

Intramolecular Cyclization of Iodosilane 1

To date, however, all such studies have focused on bimolecular cross-coupling reactions yielding linear, silicon-containing products. We were interested in investigating an intramolecular silyl-Heck reaction wherein a silyl halide could cyclize onto a pendant alkene.4 We reasoned that such reactions would allow us to study the reactivity of internal alkenes, which has not been possible in bimolecular reactions. In addition, such a reaction would access new classes of cyclic unsaturated silicon heterocycles.

Silicon-containing heterocycles are important structures in many disciplines of chemistry. Such silacycles are common motifs in silicon derivatives of drugs, known as siladrugs.5 Silacycles are also important synthetic intermediates6 and have been utilized in many total syntheses.7 Most commonly, silicon-containing rings are oxidized to form complex diols.7–8 Unsaturated silacycles also serve as unique precursors for the formation of silicon-based polymers.9 Small silacycles, such as silacyclobutanes, have been shown to be excellent nucleophiles for Hiyama-Denmark coupling reactions.10

Classically, silacycles have been synthesized from cycloadditions of reactive silenes or silylenes with dienes.11 Alternatively, intramolecular hydrosilylation is a common strategy for the synthesis of various silacycles. Speier’s catalyst (H2PtCl6) is commonly used and gives a strong preference for exo cyclizations following the Chalk-Harrod mechanism,12 while more recently, Yamamoto and Trost have independently demonstrated that endo cyclizations are possible using aluminum trichloride or a cationic ruthenium complex.13 We envisioned that an intramolecular silyl-Heck reaction could provide an alternative approach for the synthesis of silicon-containing heterocycles.

Herein, we report the first examples of intramolecular silyl-Heck reactions (Scheme 1, bottom). These studies not only provide routes to cyclic silanes, but also provide insights into the requirements of the silyl-Heck reaction. Specifically, we show that these transformations allow access to a variety of 5- and 6-membered unsaturated silicon heterocycles with moderate to good yields. Further, through a systematic study of tether length and alkene substitution and their effect on regioselectivity and efficiency, significant insight into the steric requirements of the silyl-Heck process has been gained. Finally, by tethering the alkene to the silicon electrophile, we have observed the first examples of successful silyl-Heck reactions of 1,1- and 1,2-disubstituted alkenes.

RESULTS

For initial exploration of an intramolecular silyl-Heck reaction, we sought to design a substrate that closely resembled those of our prior bimolecular reactions, which involved silyl iodides and terminal monosubstituted alkenes. To this end, 4-pentenyldimethyl iodosilane (1) was identified as a suitable substrate due to minimal steric and electronic bias. However, because of the sensitivity of the molecule towards moisture, and the propensity of trace hydroiodic acid to result in alkene isomerization, 1 could only be prepared in limited purity (ca. 80%, according 1H NMR analysis).14,15

Despite those limitations, we decided to explore the cyclization of compound 1 nonetheless. In principle, 1 can undergo either a 6-endo (2 and/or 3) or 5-exo (4) cyclization (Scheme 1). Based on the known selectivities of Heck cyclization involving carbon electrophiles,4 the 5-exo product (4) was expected to strongly predominate. However, when 1 was subjected to reaction conditions similar to those employed in our earlier work (Pd2dba3/JessePhos),1f a surprising result was observed. Instead of the expected 5-exo pathway, 1 underwent cyclization to exclusively provide a mixture of products 2 and 3 in a 1:1 ratio in 61% yield (as determined by 1H NMR against an internal standard). Apparently, these products arise from 6-endo cyclization, followed by non-selective β–hydride elimination from intermediate 6. Unfortunately, due to their volatility, 2 and 3 proved challenging to isolate and separate. However, samples of sufficient analytical purity for structural characterization were obtained using preparative gas chromatography.16 In addition, in nearly all cases in prior studies, strong preference for the allylic isomer has been observed in silyl-Heck transformations where its formation is possible. Here a mixture of allyl and vinyl isomers is obtained. It is unclear in this case if the observed alkene mixture results from kinetic or thermodynamic selectivity.

We wished to understand the origins of the seemingly unusual regioselectivity. On one hand, in all prior examples of silyl-Heck reactions,17 silylation occurs exclusively at the terminal position of the alkene - and the observed selectivity might be due to the same effect. On the other hand, 6-endo intramolecular Heck reactions using carbon-based electrophiles are not unprecedented, but typically require electronically biased alkenes18 or are thought to undergo rearrangements and other non-traditional reaction mechanisms.19 One notable exception is a recently reported Heck-cyclization from the Gevorgian lab involving a silicon-tethered substrate.20 In that case, 6-endo cyclization was also observed, which presumably is a result of the stereoelectronic effects imparted by the long Si–C bonds contained within the product. To better understand if the observed regioselectivity in the cyclization of 1 was a manifestation of the preference for the silicon center to react at the alkene terminus, or is inherent in Heck-type cyclizations involving small silacycles, we undertook a more systemic study.

To facilitate that investigation, substrates that would be easier to prepare and purify, and products that would be easier to isolate and analyze were desired. Towards this end, we elected to investigate chlorosilane substrates. We have previously shown that chlorosilanes can participate in palladium-catalyzed silyl-Heck reactions when activated in situ by the addition of iodide salts.21 Moreover, chlorosilanes can be synthesized under mild reaction conditions, potentially allowing for higher yield and purity in substrate synthesis.

Initially, we focused on preparing chlorodiphenylsilane substrates. We reasoned that the added molecular mass of the two phenyl groups would lower the volatility of the products and allow easier isolation. As predicted, we were able to prepare 7 in higher purity (>95% according to 1H NMR analysis, eq 1). Unfortunately, however, this chlorodiphenylsilane substrate proved sluggish in the silyl-Heck reaction. Even with use of lithium iodide as an additive, only 41% combined yield of products 8 and 9 was obtained.22 Interestingly, however, like the earlier cyclization, only products arising from a 6-endo cyclization were observed; no 5-exo product (10) could be detected.

|

(1) |

We suspected that the poor reactivity of 7 was due to the steric demands of the two phenyl groups attached to silicon. As a means of modulating the size of the silicon center, we then turned to chloromethylphenylsilyl substates. Encouragingly, using this electrophilic silicon center, we were able to prepare substrate 11 in analytically pure fashion. Moreover, using the combination of catalytic Pd2dba3 and JessePhos, with LiI additive, 11 underwent smooth cyclization to lead to a 1:1 mixture of 12 and 13 in 81% combined yield (Table 1, entry 1). As before, product 14 (which would arise from 5-exo cyclization) was not observed.

Table 1.

Cyclizations of Chloromethylphenyl Silanes

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst (mol %) | Combined Yield (%) | Ratio 12:13:14 |

| 1 | Pd2dba3 (5), JessePhos (10) | 81 | 1:1:0 |

| 2 | (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (5) | 88 | 1:1:0 |

Before continuing to a more exhaustive study, we also wanted to examine the nature of the catalyst. We have previously reported the use of a single-component JessePhos palladium complex as an effective precatalyst for the silyl-Heck reaction.23 The use of these precatalysts simplifies reaction setup and often leads to higher and more consistent yields. Using the single-component catalyst (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15), methyl(phenyl)silane 11 cyclized to yield a 1:1 ratio of 12 and 13 in 88% combined yield (entry 2). This catalyst system was selected for further study.

With an isolable and sufficiently reactive class of silicon electrophiles and a proper catalyst identified, we set out to study the effects of both tether length and alkene substitution on the intramolecular silyl-Heck reaction. A series of homologous substrates were prepared,16 then subjected to the silyl-Heck reaction conditions. The results of those cyclization studies are presented below.

|

(2) |

Substrate 16 bearing a four-carbon tether was prepared and subjected to the reaction conditions using catalyst 15 (eq 2). With this butenyl substrate, cyclization occurred to provide a 1:1 mixture of 5-endo products 17 and 18 in 80% combined yield. The observed result is notable as it again proved dissimilar to Heck cyclizations of carbon-electrophiles; 5-endo-trig cyclizations are typically disfavored due to the distortion required for orbital overlap.24 Although 5-endo products have been observed in Heck reactions25 to form indoles and related compounds, they are thought react through 6-membered palladacycle intermediates.25i, 26 In this case, however, the substrate lacks suitable electronic bias to favor such a pathway. Additionally, although four-membered ring formation has been observed in Heck cyclization of carbon electrophiles,27 in this case silacy-clobutane 19 resulting from 4-exo cyclization was not observed.

We also prepared the substrate bearing a tether one atom shorter yet (20, eq 3). However, when this allyl substrate was subjected to the optimized reaction conditions, no cyclized product was observed. Even at elevated temperatures, only unreacted or isomerized starting material remained.

|

(3) |

Next, we next sought to examine longer alkene tether lengths. When substrate 21 (eq 4), bearing the four-carbon tether, was subjected to the reaction conditions, products 23 and 24 were obtained in 31% combined yield as a 3:1 mixture. Interestingly, both of these products are the result of 6-exo cyclization. These are the first examples of silyl-Heck cyclizations proceeding via an exo pathway. More importantly, however, they are also the first examples of the internal silylation of an alkene using this method, and demonstrate that addition of the silicon atom to the internal carbon is possible.28 Notably, although 7-endo Heck cyclizations have been reported,20, 29 the product from 7-endo cyclization in the silyl-Heck reaction (22) was not detected, indicating that the 7-endo pathway is less favorable than internal silylation. However, the overall low yield in this reaction indicates the difficulties associated with both pathways.

|

(4) |

Unfortunately, attempting to drive larger ring cyclization with the 5-atom linker of alkene 25 failed to provide product (eq 5); neither 7- or 8-membered silacycles were observed.

|

(5) |

After determining the range of reactive chain lengths, we next turned our attention to studying the effects of alkene substitution. To date, only mono-substituted alkenes have been found to be suitable substrates in bimolecular silyl-Heck reactions. Tolerance of higher alkene substitution is presumably disfavored due to unfavorable steric interactions. A similar limitation is observed in bimolecular Heck reactions employing carbon electrophiles, wherein rates of reactivity decrease dramatically with increased olefin substitution under most reaction conditions.30,31 Related intramolecular Heck cyclizations, however, have been shown to tolerate tri- and tetra-substituted alkenes.32 Considering this background, we sought to define the tolerance of alkene substitution in the intramolecular silyl-Heck reaction.

We began with a substrate bearing a tethered 1,1-disubstituted terminal alkene (26, Scheme 2). Like other disubstituted alkenes, gem-disubstituted olefins have proven to be poor substrates in bimolecular silyl-Heck reactions. Subjecting alkene 26 to the reaction conditions gave rise to products 27 and 28 in 88% yield as a 5:1 ratio of isomers, making this the first successful example of the use of a di-substituted alkene in a silyl-Heck reaction. Consistent with the previous intramolecular cases, the reaction proceeds with exclusive 6-endo selectivity, placing the silicon atom at the terminus of the alkene. However, contrary to the previous examples the vinyl isomer is largely favored over the allylic isomers.

Scheme 2.

6-Endo Cyclization of 26

Next, we investigated the reactivity of several internal alkenes. When methyl-substituted Z-alkene 31 was subjected to the optimal reaction conditions, 5-exo product 32 was formed in 18% yield (Scheme 3). Only the Z-alkene isomer was observed, the configuration of which was established using 1- and 2-dimensional NMR methods. The geometry of the product is consistent with a Heck-like mechanism involving syn-facial migratory insertion, C–C σ-bond rotation, and syn-periplanar β-hydride elimination (via intermediates 35-37). Notably, cyclization of the closely related Z-styrenyl substrate 33 led to a very similar result in terms of product selectivity (only 34 was observed), but the reaction was considerably more efficient (49% yield). This indicated that the electronic nature of the alkene is also important in the outcome of the silyl-Heck cyclization.

Scheme 3.

5-Exo Cyclizations of 31 and 33.

The successful cyclization of 31 and 33 are significant as these are the first internal alkenes have been observed to participate in silyl-Heck reactions. Moreover, in contrast to substrates 11 and 26, which bear identical tether lengths, these substrates cyclize with complete preferential 5-exo selectivity. This indicates that in the absence of a steric preference, the stereoelectronic effects similar to those observed in Heck cyclizations of carbon-based electrophiles predominate.4a, 33

Successful cyclization of internal alkenes, however, appears to be very substrate dependent. For example, simply switching the alkene geometry of the substrate from cis to trans resulted in no observed cyclization products from substrate 38 (eq 6). This remained true even with the use of elevated temperatures and longer reaction times. We attribute the lack of reactivity to steric congestion during the migratory insertion between the groups on silicon and the methyl group of the E-alkene, which indicates the degree of difficulty associated with silyl-palladation of internal alkenes using these methods.

|

(6) |

DISCUSSION

Overall, the results presented above paint an initial picture of the steric and stereoelectronic requirements for intramolecular silyl-Heck reactions. The predominant factor in evaluating the facility of a silyl-Heck cyclization appears to depend upon the steric nature of the alkene. With tethered, terminal alkenes, both 5- and 6-endo cyclizations appear to occur readily and are dictated by the ability of the cyclization to place the large silicon group at the non-sterically encumbered terminus of the alkene. Endo-selective cyclizations can also appear to tolerate additional substitution at the internal carbon, so long as the terminal position remains unsubstituted. 3-, 4-, and 7-Endo cyclization appear to be much more challenging. In the two former cases, no cyclization products are formed. In the latter case, 6-exo cyclization is preferred but is not efficient - presumably due to the challenges of placing the silicon group at the internal carbon of the alkene. Finally, in some cases, through use of the intramolecular tether, 1,2-disubstituted alkenes can participate in silyl-Heck reactions to some extent. However, yields in these cyclizations are low, and appear to require the less sterically demanding cis-alkene geometry in order to proceed. Finally, unlike bimolecular silyl-Heck reactions where the position of the double bond in the unsaturated organosilane product is readily predicted by the nature of the starting material, intramolecular silyl-Heck reactions provide less predictable and less selective mixtures of allyl and vinyl silane products.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, for the first time we have explored the feasibility of intramolecular silyl-Heck reactions. We have found that this method is effective for the preparation of both 5- and 6-membered unsaturated silicon heterocycles, provided that the reaction can proceed to place the silicon atom at the unsubstituted terminus of the tethered alkene. Both endo and exo selective reactions are possible. Selectivity between endo and exo modes is best understood by consideration of both ring size and the steric requirements of the alkene.

These studies have also demonstrated the first examples of more highly substituted alkenes participating in silyl-Heck reactions. Both 1,1- and 1,2-disubstituted alkenes can undergo cyclization, but the success of such reactions is dependent on the geometric and steric considerations of the reaction.

Overall, these studies have provided further insights into the steric requirements of the silyl-Heck reaction, and will provide insights into how to further develop silyl-Heck reactions of highly substituted alkenes.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

General Procedure for Silyl-Heck Reactions

In a nitrogen filled glovebox, a 1-dram vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 13.9 mg, 0.125 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (47 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (175 μL, 1.25 mmol, 5.0 equiv), and PhCF3 (500 μL, 0.5M), and silyl chloride (0.25 mmol, 1.0 equiv). The vial was sealed and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. The reaction was removed from heat, allowed to cool to rt, opened to air, and 1,3,5-trimethoxy benzene (28 mg, 2/3 equiv) was added. A small aliquot was taken for NMR analysis without concentration, the sample was returned to the crude mixture, then filtered through Celite with Et2O and concentrated in vacuo. The crude oil was purified via flash silica gel chromatography with the indicated eluent in parenthesis.

1,1-Dimethyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrosiline (2) and 1,1-Dimethyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydrosiline (3)

In a nitrogen filled glovebox, a 1-dram vial with a magnetic stir bar was charged with trisdibenzyladinedipalladium (Pd2dba3, 11 mg), JessePhos (12 mg), Et3N (175 μL) and PhCF3 (500 μL). The vial was capped, heated at 45 °C, and stirred for 5 min. The vial was removed from heat and silyliodide 1 (64 mg), was added in one portion without cooling. The vial was then resealed and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. The reaction was removed from heat and allowed to cool to rt. Mesitylene (35 μL) was added and a small aliquot was taken for NMR analysis without concentration. The volatile organic compounds (including products) of the crude mixture were vacuum transferred, to separate them from the catalyst and ligand, and analytical amounts of the two isomeric products were purified to ≥70% purity by preparatory gas chromatography. 2 (vinylsilane): 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 6.63 (dt, J = 14.1, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (dt, J = 14.1, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 2.04 – 1.92 (m, 2H), 1.78 – 1.64 (m, 2H), 0.68 – 0.57 (m, 2H), 0.08 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, C6D6) δ = 149.1, 127.1, 31.2, 21.5, 12.3, −1.6. HRMS (LIFDI) calcd for [C7H14Si]: 126.0865, found: 126.0847. 3 (allylsilane): 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 5.86 (dtt, J = 10.1, 5.0, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 5.74 (dtt, J = 10.5, 4.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 2.21 (tdt, J = 6.4, 3.8, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 1.17 (dq, J = 4.0, 1.9 Hz, 2H), 0.63 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 0.00 (s, 6H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, C6D6) δ = 130.5, 126.2, 23.2, 13.3, 10.3, −2.5. HRMS (LIFDI) calcd for [C7H14Si]: 126.0865, found: 126.0835.

1-Methyl-1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrosiline (12) and 1-Methyl-1-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydrosiline (13)

According to the general procedure, silyl chloride 11 (56 mg, 0.25 mmol), (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 13.9 mg, 0.125 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (47 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (175 μL, 1.25 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and PhCF3 (500 μL, 0.5M) were combined and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H NMR revealed an 88% yield. The crude material was purified via silica gel chromatography (hexanes) to afford a mixture of 12 and 13 as a colorless oil (38 mg, 81%): 12 (vinylsilane): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59 – 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.39 – 7.32 (m, 3H), 6.91 (dt, J = 14.1, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 5.91 – 5.79 (m, 1H), 2.25 – 2.18 (m, 2H), 1.90 – 1.80 (m, 2H), 1.03 – 0.80 (m, 2H), 0.35 (s, 3H); 13 (allylsilane): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 – 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.40 – 7.32 (m, 3H), 5.91 – 5.80 (m, 1H), 5.78 – 5.66 (m, 1H), 2.36 – 2.27 (m, 2H), 1.63 – 1.36 (m, 2H), 1.04 – 0.80 (m, 2H), 0.33 (s, 3H); 12 and 13 (mixture): 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.8, 139.0, 138.9, 134.2, 133.8, 130.7, 129.2, 129.1, 128.0, 127.9, 125.9, 124.7, 31.1, 23.0, 21.2, 12.1, 11.6, 9.4, −3.0, −3.8; FTIR (cm−1) 2907, 1590, 1427, 1251, 1111, 809, 699. HRMS (CI) m/z, calcd for [C12H16Si]: 188.1021; found: 188.1012.

1-Methyl-1-phenyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-silole (17) and 1-Methyl-1-phenyl-2,5-dihydro-1H-silole (18)

According to the general procedure, silyl chloride 16 (53 mg, 0.25 mmol), (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 13.9 mg, 0.125 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (47 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (175 μL, 1.25 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and PhCF3 (500 μL, 0.5M) were combined and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H NMR revealed an 80% yield. The crude material was purified via silica gel chromatography (pentane) to afford a mixture of 17 and 18 as a colorless oil (31 mg, 71%): 17 (vinylsilane): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55 – 7.48 (m, 2H), 7.42 – 7.32 (m, 3H), 7.00 (dt, J = 10.1, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 6.07 (dt, J = 10.1, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 2.70 – 2.51 (m, 2H), 1.06 – 0.82 (m, 2H), 0.48 (s, 3H); 18 (allylsilane): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 – 7.55 (m, 2H), 7.43 – 7.31 (m, 3H), 5.97 (s, 2H), 1.69 – 1.43 (m, 4H), 0.48 (s, 3H); 17 and 18 (mixture): 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.2, 138.9, 138.3, 134.0, 133.8, 131.2, 129.4, 129.2, 128.7, 128.0, 127.9, 32.4, 17.7, 8.8, −3.0, −3.7; FTIR (cm−1) 3019, 2905, 1114. HRMS (CI) m/z, calcd for [C11H14Si]: 174.0865; found: 174.0858.

1-Methyl-2-methylene-1-phenylsilinane (23) and 1,6-Dimethyl-1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrosiline (24)

According to the general procedure, silyl chloride 21 (240 mg, 1.0 mmol), (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 56 mg, 0.5 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (188 mg, 1.4 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (700 μL, 5.0 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and PhCF3 (2 mL, 0.5M) were combined and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H NMR revealed a 31% yield. The crude material was purified via silica gel chromatography (hexanes) to afford a mixture of 23 and 24 as a colorless oil (23 mg, 12%): 23 (exo): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.59 – 7.51 (m, 3H), 7.40 – 7.33 (m, 3H), 5.60 (dd, J = 3.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 5.19 (dt, J = 3.6, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 2.49 – 2.27 (m, 2H), 1.96 – 1.83 (m, 1H), 1.70 – 1.60 (m, 1H), 1.54 – 1.39 (m, 1H), 1.20 – 1.09 (m, 1H), 0.86 – 0.72 (m, 1H), 0.34 (s, 3H); 24 (endo): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 – 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.43 – 7.30 (m, 3H), 6.49 (dq, J = 4.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 2.23 – 2.12 (m, 2H), 1.84 – 1.76 (m, 2H), 1.71 (q, J = 2.0 Hz, 3H), 1.00 – 0.89 (m, 1H), 0.86 – 0.71 (m, 1H), 0.37 (s, 3H); 23 and 24 (mixture): 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.8, 143.9, 138.2, 137.0, 134.4, 134.3, 131.9, 129.2, 129.1, 127.9, 127.9, 123.5, 40.0, 31.0, 30.6, 24.5, 21.9, 21.4, 13.7, 11.9, −4.3, −4.9; FTIR (cm−1) 2921, 2852, 1653. HRMS (CI) m/z, calcd for [C13H18Si]: 202.1178; found: 202.1176.

1,5-Dimethyl-1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrosiline (27) and 1,5-Dimethyl-1-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydrosiline (28)

According to the general procedure, silyl chloride 26 (60 mg, 0.25 mmol), (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 13.9 mg, 0.125 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (47 mg, 0.35 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (175 μL, 1.25 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and PhCF3 (500 μL, 0.5M) were stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H NMR revealed an 88% yield. The crude material was purified via silica gel chromatography (pentane) to afford a mixture of 27 and 28 as a colorless oil (42 mg, 82%): 27 (vinylsilane): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 – 7.50 (m, 2H), 7.41 – 7.31 (m, 3H), 5.51 (s, 1H), 2.11 (t, 2H), 1.89 (d, 3H), 1.88 – 1.79 (m, 2H), 0.94 – 0.69 (m, 2H), 0.31 (s, 3H); 28 (allylsilane): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 – 7.49 (m, 2H), 7.41 – 7.31 (m, 3H), 5.51 (s, 1H), 2.29 – 2.21 (m, 2H), 1.79 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 3H), 1.53 – 1.29 (m, 2H), 0.97 – 0.68 (m, 2H), 0.31 (s, 3H); 27 and 28 (mixture): 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.0, 139.6, 134.2, 133.8, 129.1, 128.9, 127.9, 127.8, 124.3, 118.4, 100.1, 35.3, 29.5, 28.5, 22.8, 21.6, 17.4, 10.7, 9.0, −2.8; FTIR (cm−1) 2924, 1608, 1427, 1250, 1111, 815, 731, 698. HRMS (CI) m/z, calcd for [C13H18Si]: 202.1178; found: 202.1174.

(Z)-2-Ethylidene-1-methyl-1-phenylsilolane (32)

According to the general procedure, silyl chloride 31 (240 mg, 1.0 mmol), (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 56 mg, 0.5 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (188 mg, 1.4 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (700 μL, 5.0 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and PhCF3 (2 mL, 0.5M) were combined and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H NMR revealed a 18% yield. The crude material was purified via silica gel chromatography (pentane) to afford 32 as a colorless oil (36 mg, 17%): 1H NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.61 – 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.40 – 7.30 (m, 3H), 6.29 (qt, J = 6.6, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 2.39 – 2.33 (m, 2H), 1.85 – 1.69 (m, 2H), 1.64 (dt, J = 6.7, 1.9 Hz, 3H), 0.98 – 0.81 (m, 2H), 0.50 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ 142.5, 138.1, 134.3, 133.8, 129.1, 127.9, 39.2, 25.5, 19.8, 15.0, −3.9; FTIR (cm−1) 2916, 1428, 1250, 1112, 732, 698. HRMS (CI) m/z, calcd for [C13H18Si]: 202.1178; found: 202.1177.

(Z)-1-Methyl-2-(4-methylbenzylidene)-1-phenylsilolane (34)

According to the general procedure, silyl chloride 33 (158 mg, 0.5 mmol), (JessePhos)2PdCl2 (15, 28 mg, 0.25 mmol, 5 mol %), LiI (94 mg, 0.7 mmol, 1.4 equiv), Et3N (350 μL, 2.5 mmol, 5.0 equiv) and PhCF3 (1.0 mL, 0.5M) were combined and stirred at 45 °C for 24 h. Analysis of the crude reaction mixture via 1H NMR revealed a 49% yield. The crude material was purified via silica gel chromatography (hexanes) to afford 34 as a colorless oil (57 mg, 41%): 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.58 – 7.52 (m, 2H), 7.37 – 7.31 (m, 3H), 7.26 (s, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.94 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.66 – 2.58 (m, 2H), 2.25 (s, 3H), 1.98 – 1.85 (m, 1H), 1.76 – 1.63 (m, 1H), 0.97 (dd, J = 7.8, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 0.38 (s, 3H); 1H NMR (400 MHz, C6D6) δ 7.62 – 7.53 (m, 2H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.26 – 7.21 (m, 2H), 7.22 – 7.17 (m, 3H), 6.79 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.66 – 2.52 (m, 2H), 1.98 (s, 3H), 1.94 – 1.79 (m, 1H), 1.71 – 1.57 (m, 1H), 0.99 – 0.84 (m, 2H), 0.41 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.0, 139.1, 138.4, 136.6, 136.6, 134.2, 129.2, 128.8, 128.0, 127.9, 42.8, 24.8, 21.3, 15.8, −5.0 (15_C); 13C NMR (101 MHz, C6D6) δ 143.6, 140.0, 138.6, 137.1, 136.8, 134.5, 129.5, 129.1, 128.3, 43.0, 25.1, 21.1, 16.1, −4.9; FTIR (cm−1) 2920, 1510, 1428, 1110, 809, 699. HRMS (CI) m/z, calcd for [C19H22Si]: 278.1491; found: 278.1493.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Silyl-Heck Reactions

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The University of Delaware and the National Science Foundation (CAREER CHE-1254360 and CHE-1800011) are gratefully acknowledged for support. Gelest, Inc. (Topper Grant Program) is acknowledged for gift of chemical supplies. Data was acquired at UD on instruments obtained with the assistance of NSF and NIH funding (NSF CHE-0421224, CHE-0840401, CHE-1229234; NIH S10 OD016267, S10 RR026962, P20 GM104316, P30 GM110758).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1) (a).McAtee JR; Martin SES; Ahneman DT; Johnson KA; Watson DA ”Preparation of Allyl and Vinyl Silanes by the Palladium-Catalyzed Silylation of Terminal Olefins: A Silyl-Heck Reaction,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 3663–3667; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Martin SES; Watson DA ”Preparation of Vinyl Silyl Ethers and Disiloxanes via the Silyl-Heck Reaction of Silyl Ditriflates,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 13330–13333; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martin SES; Watson DA ”Silyl-Heck Reactions for the Preparation of Unsaturated Organosilanes,” Synlett 2013, 24, 2177–2182; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) McAtee JR; Martin SES; Cinderella AP; Reid WB; Johnson KA; Watson DA ”The First Example of Nickel-Catalyzed Silyl-Heck Reactions: Direct Activation of Silyl Triflates without Iodide Additives,” Tetrahedron 2014, 70, 4250–4256; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) McAtee JR; Yap GPA; Watson DA ”Rational Design of a Second Generation Catalyst for Preparation of Allylsilanes Using the Silyl-Heck Reaction,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 10166–10172; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) McAtee JR; Krause SB; Watson DA ”Simplified Preparation of Trialkylvinylsilanes via the Silyl-Heck Reaction Utilizing a Second Generation Catalyst,” Adv. Synth. Catal 2015, 357, 2317–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2) (a).Matsumoto K; Huang J; Naganawa Y; Guo H; Beppu T; Sato K; Shimada S; Nakajima Y ”Direct Silyl–Heck Reaction of Chlorosilanes,” Org. Lett 2018, 20, 2481–2484; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Naganawa Y; Guo H; Sakamoto K; Nakajima Y ”Nickel-Catalyzed Selective Cross-Coupling of Chlorosilanes with Organoaluminum Reagents,” ChemCatChem 2019, 11, 3756–3759. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Recently we have also developed related silyl-Negishi reactions of silyliodides and silyl-Kumada-Corriu reactions of silyl chlorides, see: (a) Cinderella AP; Vulovic B; Watson DA ”Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Silyl Electrophiles with Alkylzinc Halides: A Silyl-Negishi Reaction,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7741–7744; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vulovic B; Cinderella AP; Watson DA ”Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Monochlorosilanes and Grignard Reagents,” ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 8113–8117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4) (a).Gibson SE; Middleton RJ ”The Intramolecular Heck Reaction,” Contemp. Org. Synth 1996, 3, 447–471; [Google Scholar]; (b) Shibasaki M; Boden CDJ; Kojima A ”The Asymmetric Heck Reaction,” Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 7371–7395; [Google Scholar]; (c) Beletskaya IP; Cheprakov AV ”The Heck Reaction as a Sharpening Stone of Palladium Catalysis,” Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 3009–3066; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Link JT, The Intramolecular Heck Reaction In Organic Reactions, John Wiley & Sons, Inc: 2002; pp 157–534; [Google Scholar]; (e) Dounay AB; Overman LE ”The Asymmetric Intramolecular Heck Reaction in Natural Product Total Synthesis,” Chem. Rev 2003, 103, 2945–2964; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zeni G; Larock RC ”Synthesis of Heterocycles via Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Addition,” Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 4644–4680; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Geoghegan K, Regioselectivity in the Heck (Mizoroki-Heck) Reaction In Selectivity in the Synthesis of Cyclic Sulfonamides: Application in the Synthesis of Natural Products, Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp 17–41. [Google Scholar]

- (5) (a).Díez-González S; Paugam R; Blanco L ”Synthesis of 1-Silabicyclo[4.4.0]dec-5-en-4-ones: A Model of the A and B Rings of 10-Silatestosterone,” Eur. J. Org. Chem 2008, 2008, 3298–3307; [Google Scholar]; (b) Franz AK; Wilson SO ”Organosilicon Molecules with Medicinal Applications,” J. Med. Chem 2013, 56, 388–405; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ramesh R; Reddy DS ”Zinc Mediated Allylations of Chlorosilanes Promoted by Ultrasound: Synthesis of Novel Constrained Sila Amino Acids,” Org. Biomol. Chem 2014, 12, 4093–4097; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Igawa K; Yoshihiro D; Abe Y; Tomooka K ”Enantioselective Synthesis of Silacyclopentanes,” Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 5814–5818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Fensterbank L; Malacria M; Sieburth SMN ”Intramolecular Reactions of Temporarily Silicon-Tethered Molecules,” Synthesis 1997, 1997, 813–854. [Google Scholar]

- (7) (a).Brummond KM; Sill PC; Chen H ”The First Total Synthesis of 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 and the Unambiguous Assignment of the C14 Stereochemistry,” Org. Lett 2004, 6, 149–152; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sellars JD; Steel PG ”Application of Silacyclic Allylsilanes to the Synthesis of β-Hydroxy-δ-lactones: Synthesis of Prelactone B,” Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 5588–5595. [Google Scholar]

- (8) (a).Brummond KM; Sill PC; Rickards B; Geib SJ ”A Silicon-Tethered Allenic Pauson–Khand Reaction,” Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 3735–3738; [Google Scholar]; (b) Kuznetsov A; Gevorgyan V ”General and Practical One-Pot Synthesis of Dihydrobenzosiloles from Styrenes,” Org. Lett 2012, 14, 914–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9) (a).Birot M; Pillot J-P; Dunogues J ”Comprehensive Chemistry of Polycarbosilanes, Polysilazanes, and Polycarbosilazanes as Precursors of Ceramics,” Chem. Rev 1995, 95, 1443–1477; [Google Scholar]; (b) Anhaus JT; Clegg W; Collingwood SP; Gibson VC ”Novel Silicon-Containing Hydrocarbon Rings and Polymers via Metathesis: X-Ray Crystal Structure of cis,cis-1,1,6,6-Tetraphenyl-1,6-disilacyclodeca-3,8-diene,” J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1991, 1720–1722; [Google Scholar]; (c) Hiroshi Y; Masato T ”Transition Metal-Catalyzed Synthesis of Silicon Polymers,” Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1995, 68, 403–419; [Google Scholar]; (d) Matsumoto K; Shimazu H; Deguchi M; Yamaoka H ”Anionic Ring-Opening Polymerization of Silacyclobutane Derivatives,” J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem 1997, 35, 3207–3216. [Google Scholar]

- (10) (a).Denmark SE; Choi JY ”Highly Stereospecific, Cross-Coupling Reactions of Alkenylsilacyclobutanes,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 5821–5822; [Google Scholar]; (b) Denmark SE; Wu Z ”Synthesis of Unsymmetrical Biaryls from Arylsilacyclobutanes,” Org. Lett 1999, 1, 1495–1498; [Google Scholar]; (c) Denmark SE; Wang Z ”1-Methyl-1-vinyl- and 1-Methyl-1-(prop-2-enyl)silacyclobutane: Reagents for Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Aryl Halides,” Synthesis 2000, 2000, 999–1003; [Google Scholar]; (d) Denmark SE; Wehrli D; Choi JY ”Convergence of Mechanistic Pathways in the Palladium(0)-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Alkenylsilacyclobutanes and Alkenylsilanols,” Org. Lett 2000, 2, 2491–2494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11) (a).Hermanns J; Schmidt B ”Five- and Six-membered Silicon-Carbon Heterocycles. Part 1. Synthetic Methods for the Construction of Silacycles,” J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1998, 2209–2230; [Google Scholar]; (b) Ottosson H; Steel PG ”Silylenes, Silenes, and Disilenes: Novel Silicon-Based Reagents for Organic Synthesis?,” Chem. Eur. J 2006, 12, 1576–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12) (a).Fessenden RJ; Kray WD ”Silicon Heterocyclic Compounds. Ring Closure by Hydrosilation,” J. Org. Chem 1973, 38, 87–89; [Google Scholar]; (b) Swisher JV; Chen H-H ”Silicon Heterocyclic Compounds I. Ring Size Effect in Ring Closure by Hydrosilation,” J. Organomet. Chem 1974, 69, 83–91; [Google Scholar]; (c) Tamao K; Maeda K; Tanaka T; Ito Y ”Intramolecular Hydrosilation of Acetylenes: Regioselective Functionalization of Homopropargyl Alcohols,” Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 6955–6956; [Google Scholar]; (d) Steinmetz MG; Udayakumar BS ”Chloroplatinic Acid Catalyzed Cyclization of Silanes Bearing Pendant Acetylenic Groups,” J. Organomet. Chem 1989, 378, 1–15; [Google Scholar]; (e) Ito Y; Suginome M; Murakami M ”Palladium(II) Acetate-tert-alkyl Isocyanide as a Highly Efficient Catalyst for the Inter- and Intramolecular Bis-silylation of Carbon-Carbon Triple Bonds,” J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 1948–1951; [Google Scholar]; (f) Sashida H; Kudoda A ”A Stereospecific Preparation of (E)-1,1-Dimethyl-2-methylidenesilachromenes by Platinum-Catalyzed Intramolecular Hydrosilylation,” Synthesis 1999, 1999, 921–923. [Google Scholar]

- (13) (a).Sudo T; Asao N; Yamamoto Y ”Synthesis of Various Silacycles via the Lewis Acid-Catalyzed Intramolecular Trans-Hydrosilylation of Unactivated Alkynes,” J. Org. Chem 2000, 65, 8919–8923; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Trost BM; Ball ZT ”Intramolecular Endo-Dig Hydrosilylation Catalyzed by Ruthenium: Evidence for a New Mechanistic Pathway,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 30–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kunai A; Ohshita J ”Selective Synthesis of Halosilanes from Hydrosilanes and Utilization for Organic Synthesis,” J. Organomet. Chem 2003, 686, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- (15).The remainder being inseparable internal alkene isomers.

- (16).See Supporting Information for details.

- (17) (a).Chatani N; Amishiro N; Murai S ”A New Catalytic Reaction Involving Oxidative Addition of Iodotrimethylsilane (Me3SiI) to Pd(0). Synthesis of Stereodefined Enynes by the Coupling of Me3SiI, Acetylenes, and Acetylenic Tin Reagents,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 1991, 113, 7778–7780; [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiroshi Y; Toshi-aki K; Teruyuki H; Masato T ”Heck-type Reaction of lodotrimethylsilane with Olefins Affording Alkenyltrimethylsilanes,” Chem. Lett 1991, 20, 761–762; [Google Scholar]; (c) Chatani N; Amishiro N; Morii T; Yamashita T; Murai S ”Pd-Catalyzed Coupling Reaction of Acetylenes, Iodotrimethylsilane, and Organozinc Reagents for the Stereoselective Synthesis of Vinylsilanes,” J. Org. Chem 1995, 60, 1834–1840. [Google Scholar]

- (18) (a).Grigg R; Stevenson P; Worakun T ”Rhodium- and Palladium-catalysed Formation of Conjugated Mono- and Bis-exocyclic Dienes. 5-Exo-Trig versus 6-Endo-Trig Cyclisations,” J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1984, 1073–1075; [Google Scholar]; (b) Hegedus LS; Sestrick MR; Michaelson ET; Harrington PJ ”Palladium-Catalyzed Reactions in the Synthesis of 3- and 4-Substituted Indoles. 4,” J. Org. Chem 1989, 54, 4141–4146; [Google Scholar]; (c) Dankwardt JW; Flippin LA ”Palladium-Mediated 6-endo-trig Intramolecular Cyclization of N-Acryloyl-7-bromoindolines. A Regiochemical Variant of the Intramolecular Heck Reaction,” J. Org. Chem 1995, 60, 2312–2313; [Google Scholar]; (d) Kim SH; Lee S; Lee HS; Kim JN ”Regioselective Synthesis of Poly-substituted Naphthalenes via a Pd-Catalyzed Cyclization of Modified Baylis–Hillman Adducts: Selective 6-endo Heck Reaction and an Aerobic Oxidation Cascade,” Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 6305–6309. [Google Scholar]

- (19) (a).Terpko MO; Heck RF ”Rearrangement in the Palladium-Catalyzed Cyclization of α-Substituted N-Acryloyl-o-Bromoanilines,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979, 101, 5281–5283; [Google Scholar]; (b) Owczarczyk Z; Lamaty F; Vawter EJ; Negishi E ”Apparent Endo-Mode Cyclic Carbopalladation With Inversion of Alkene Configuration via Exo-Mode Cyclization-Cyclopropanation Rearrangement,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 1992, 114, 10091–10092; [Google Scholar]; (c) Albéniz AC; Espinet P; Lin Y-S ”Cyclization versus Pd−H Elimination−Readdition: Skeletal Rearrangement of the Products of Pd−C6F5 Addition to 1,4-Pentadienes,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 7145–7152; [Google Scholar]; (d) Gajewski JJ; Benner CW; Stahlly BN; Hall RF; Sato RI ”Cross-Conjugated Biradicals: Kinetics and Kinetic Isotope Effects in the Thermal Isomerizations of cis- and trans-2,3-Dimethylemethylnecyclopropane, cis- and trans-3,4-Dimethyl-1,2-dimethylenecyclobutane, and of 1,2,8,9-Decatetraene,” Tetrahedron 1982, 38, 853–862; [Google Scholar]; (e) Grigg R; Sridharan V; Sukirthalingam S ”Alkylpalladium(II) Species. Reactive Intermediates in a Bis-cyclisation Route to Strained Polyfused Ring Systems,” Tetrahedron Lett. 1991, 32, 3855–3858; [Google Scholar]; (f) Rawal VH; Michoud C ”An Unexpected Heck Reaction. Inversion of Olefin Geometry Facilitated by the Apparent Intramolecular Carbamate Chelation of the s-Palladium Intermediate,” J. Org. Chem 1993, 58, 5583–5584. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Parasram M; Iaroshenko VO; Gevorgyan V ”Endo-Selective Pd-Catalyzed Silyl Methyl Heck Reaction,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 17926–17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21) (a).Olah GA; Narang SC; Gupta BGB; Malhotra R ”Synthetic Methods and Reactions. 62. Transformations with Chlorotrimethylsilane/Sodium Iodide, A Convenient in Situ Iodotrimethylsilane Reagent,” J. Org. Chem 1979, 44, 1247–1251; [Google Scholar]; (b) Lissel M; Drechsler K ”Ein einfaches Verfahren zur Herstellung von lodotrimethylsilan,” Synthesis 1983, 1983, 459. [Google Scholar]

- (22).In this, and other cases where lower yields were observed, the primary byproducts resulted from hydrolysis of the starting material upon workup and related alkene isomers.

- (23) (a).Reid WB; Spillane JJ; Krause SB; Watson DA ”Direct Synthesis of Alkenyl Boronic Esters from Unfunctionalized Alkenes: A Boryl-Heck Reaction,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 5539–5542; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Krause SB; McAtee JR; Yap GPA; Watson DA ”A Bench-Stable, Single-Component Precatalyst for Silyl–Heck Reactions,” Org. Lett 2017, 19, 5641–5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24) (a).Baldwin JE ”Rules for Ring Closure,” J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1976, 734–736; [Google Scholar]; (b) Baldwin JE; Cutting J; Dupont W; Kruse L; Silberman L; Thomas RC ”5-Endo-Trigonal Reactions: A Disfavoured Ring Closure,” J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1976, 736–738; [Google Scholar]; (c) Baldwin JE; Thomas RC; Kruse LI; Silberman L ”Rules for Ring Closure: Ring Formation by Conjugate Addition of Oxygen Nucleophiles,” J. Org. Chem 1977, 42, 3846–3852. [Google Scholar]

- (25) (a).Iida H; Yuasa Y; Kibayashi C ”Intramolecular Cyclization of Enaminones Involving Arylpalladium Complexes. Synthesis of Carbazoles,” J. Org. Chem 1980, 45, 2938–2942; [Google Scholar]; (b) Shaw KJ; Luly JR; Rapoport H ”Routes to Mitomycins. Chirospecific Synthesis of Aziridinomitosenes,” J. Org. Chem 1985, 50, 4515–4523; [Google Scholar]; (c) Sakamoto T; Nagano T; Kondo Y; Yamanaka H ”Condensed Heteroaromatic Ring Systems; XVII: Palladium-Catalyzed Cyclization of β-(2-Halophenyl)amino Substituted α,β-Unsaturated Ketones and Esters to 2,3-Disubstituted Indoles,” Synthesis 1990, 1990, 215–218; [Google Scholar]; (d) Michael JP; Chang S-F; Wilson C ”Synthesis of Pyrrolo[1,2-α]indoles by Intramolecular Heck Reaction of N-(2-Bromoaryl) Enaminones,” Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 8365–8368; [Google Scholar]; (e) Koerber-Plé K; Massiot G ”Synthesis of an Unusual 2,3,4-Trisubstituted Indole Derivative Found in the Antibiotic Nosiheptide,” Synlett 1994, 1994, 759–760; [Google Scholar]; (f) Chen L-C; Yang S-C; Wang H-M ”Palladium-Catalyzed Synthesis of 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-4-oxo-β-carbolines,” Synthesis 1995, 1995, 385–386; [Google Scholar]; (g) Chen C.-y.; Lieberman DR; Larsen RD; Verhoeven TR; Reider PJ ”Syntheses of Indoles via a Palladium-Catalyzed Annulation between Iodoanilines and Ketones,” J. Org. Chem 1997, 62, 2676–2677; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Henke BR; Aquino CJ; Birkemo LS; Croom DK; Dougherty RW; Ervin GN; Grizzle MK; Hirst GC; James MK; Johnson MF; Queen KL; Sherrill RG; Sugg EE; Suh EM; Szewczyk JW; Unwalla RJ; Yingling J; Willson TM ”Optimization of 3-(1H-Indazol-3-ylmethyl)-1,5-benzodiazepines as Potent, Orally Active CCK-A Agonists,” J. Med. Chem 1997, 40, 2706–2725; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Grigg R; Savic V ”Palladium Catalysed Synthesis of Pyrroles from Enamines,” Chem. Commun 2000, 873–874; [Google Scholar]; (j) Yamazaki K; Kondo Y ”Immobilized α-Diazophosphonoacetate as a Versatile Key Precursor for Palladium Catalyzed Indole Synthesis on a Polymer Support,” Chem. Commun 2002, 210–211; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Ackermann L; Kaspar LT; Gschrei CJ ”Hydroamination/Heck Reaction Sequence for a Highly Regioselective One-pot Synthesis of Indoles Using 2-Chloroaniline,” Chem. Commun 2004, 2824–2825; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Watanabe T; Arai S; Nishida A ”Novel Synthesis of Fused Indoles by the Palladium-Catalyzed Cyclization of N-Cycloalkenyl-o-haloanilines,” Synlett 2004, 2004, 907–909. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ichikawa J; Sakoda K; Mihara J; Ito N ”Heck-type 5-endo-trig Cyclizations Promoted by Vinylic Fluorines: Ring-Rluorinated Indene and 3H-Pyrrole Syntheses from 1,1-Difluoro-1-alkenes,” J. Fluorine Chem 2006, 127, 489–504. [Google Scholar]

- (27) (a).Bräse S ”Synthesis of Bis(enolnonaflates) and their 4-exo-trig-Cyclizations by Intramolecular Heck Reactions,” Synlett 1999, 1999, 1654–1656; [Google Scholar]; (b) Yoshito T; Tetsuya S; Masahiro M; Masakatsu N ”Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Benzyl Ketones and α,β-Unsaturated Carbonyl and Phenolic Compounds with o-Dibromobenzenes to Produce Cyclic Products,” Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn 1999, 72, 2345–2350; [Google Scholar]; (c) Innitzer A; Brecker L; Mulzer J ”Functionalized Cyclobutanes via Heck Cyclization,” Org. Lett 2007, 9, 4431–4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28). In this case, 24 must result from isomerization of 23 after its initial formation.

- (29) (a).Gibson SE; Middleton RJ ”Synthesis of 7-, 8- and 9-Membered Rings via endo Heck Cyclisations of Amino Acid Derived Substrates,” J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1995, 1743–1744; [Google Scholar]; (b) Rigby JH; Hughes RC; Heeg MJ ”Endo-Selective Cyclization Pathways in the Intramolecular Heck Reaction,” J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7834–7835; [Google Scholar]; (c) E. Gibson S; Guillo N; J. Middleton R; Thuilliez A; J. Tozer M ”Synthesis of Conformationally Constrained Phenylalanine Analogues via 7-, 8- and 9-endo Heck Cyclisations,” J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans 1 1997, 447–456; [Google Scholar]; (d) Iimura S; Overman LE; Paulini R; Zakarian A ”Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Guanacastepene N Using an Uncommon 7-Endo Heck Cyclization as a Pivotal Step,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 13095–13101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Heck RF, Palladium-Catalyzed Vinylation of Organic Halides In Organic Reactions, John Wiley & Sons, Inc: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- (31) (a).Sigman has recently developed a series of bimolecular redox relay Heck reactions that tolerate higher degrees of alkene substitution, see: Mei T-S; Patel HH; Sigman MS ”Enantioselective Construction of Remote Quaternary Stereocentres,” Nature 2014, 508, 340–344; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang C; Santiago CB; Crawford JM; Sigman MS ”Enantioselective Dehydrogenative Heck Arylations of Trisubstituted Alkenes with Indoles to Construct Quaternary Stereocenters,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 15668–15671; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Patel HH; Sigman MS ”Enantioselective Palladium-Catalyzed Alkenylation of Trisubstituted Alkenols to form Allylic Quaternary Centers,” J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 14226–14229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32) (a).Earley WG; Oh T; Overman LE ”Synthesis Studies Directed Toward Gelsemine. Preparation of an Advanced Pentacyclic Intermediate,” Tetrahedron Lett. 1988, 29, 3785–3788; [Google Scholar]; (b) Madin A; Overman LE ”Controlling Stereoselection in Intramolecular Heck Reactions by Tailoring the Palladium Catalyst,” Tetrahedron Lett. 1992, 33, 4859–4862; [Google Scholar]; (c) Ashimori A; Overman LE ”Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Quarternary Carbon Centers. Palladium-Catalyzed Formation of Either Enantiomer of Spirooxindoles and Related Spirocyclics Using a Single Enantiomer of a Chiral Diphosphine Ligand,” J. Org. Chem 1992, 57, 4571–4572; [Google Scholar]; (d) Ashimori A; Matsuura T; Overman LE; Poon DJ ”Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Either Enantiomer of Physostigmine. Formation of Quaternary Carbon Centers with High Enantioselection by Intramolecular Heck Reactions of (Z)-2-Butenanilides,” J. Org. Chem 1993, 58, 6949–6951. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Overman LE ”Application of Intramolecular Heck Reactions for Forming Congested Quaternary Carbon Centers in Complex Molecule Total Synthesis,” Pure Appl. Chem 1994, 66, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.