Abstract

Background

The novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), infected over 3300 healthcare workers in early 2020 in China. Little information is known about nosocomial infections of healthcare workers in the initial period. We analysed data from healthcare workers with nosocomial infections in Wuhan Union Hospital (Wuhan, China) and their family members.

Methods

We collected and analysed data on exposure history, illness timelines and epidemiological characteristics from 25 healthcare workers with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and two healthcare workers in whom COVID-19 was highly suspected, as well as 10 of their family members with COVID-19, between 5 January and 12 February 2020. The demographics and clinical features of the 35 laboratory-confirmed cases were investigated and viral RNA of 12 cases was sequenced and analysed.

Results

Nine clusters were found among the patients. All patients showed mild to moderate clinical manifestation and recovered without deterioration. The mean period of incubation was 4.5 days, the mean±sd clinical onset serial interval (COSI) was 5.2±3.2 days, and the median virus shedding time was 18.5 days. Complete genomic sequences of 12 different coronavirus strains demonstrated that the viral structure, with small irrelevant mutations, was stable in the transmission chains and showed remarkable traits of infectious traceability.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 can be rapidly transmitted from person to person, regardless of whether they have symptoms, in both hospital settings and social activities, based on the short period of incubation and COSI. The public health service should take practical measures to curb the spread, including isolation of cases, tracing close contacts, and containment of severe epidemic areas. Besides this, healthcare workers should be alert during the epidemic and self-quarantine if self-suspected of infection.

Short abstract

SARS-CoV-2 can be rapidly transmitted from person to person in nosocomial and social settings, despite patients having no symptoms https://bit.ly/34BHtB5

Introduction

17 years after the 2003 epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [1, 2], a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was isolated from bronchoalveolar lavage of several patients with unknown origin pneumonia in Wuhan City, China [3]. SARS-CoV-2 has caused coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) across the country and abroad. A total of 83 157 COVID-19 cases with 4.02% mortality has been reported in China up to 7 April 2020 [4]. The confirmed cases have been identified in >180 countries and regions around the world, and >1 300 000 people have been infected globally outside China, including 78 932 deaths [5]. The hunt for patient zero is critical, but epidemiological investigations are often complex and unclear [6]. A COVID-19 patient usually presents with fever, a nonproductive cough, myalgia and malaise. Symptoms, including a productive cough and headache, are less common. Dyspnoea is observed in more than one-quarter of patients. Cases with persistent lymphopenia usually develop fatal comorbidities, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute cardiac injury, secondary infection and multiorgan dysfunction [7–9].

SARS-CoV-2 is a positive-sense and single-stranded RNA virus of zoonotic origin belonging to Betacoronavirus lineage B [3]. It has successfully crossed the animal-to-human barrier and proved to be capable of epidemic spread and may even have endemic persistence in the human population [10]. The calculated R0 of SARS-CoV-2 is as high as 2.68 [11], making prevention measures and intervention tactics very challenging. Unfortunately, current general hospital settings in Wuhan and many other cities are acting as epidemic hot spots to facilitate transmission and exacerbate spread [12]. So far, >3300 healthcare workers (HCWs) in China have been diagnosed as infected, mainly through nosocomial transmission [13]. HCWs are among the first to suffer during the epidemic. The transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in hospitals in the initial period, especially among HCWs, are important for deeper understanding of the epidemiology of the disease.

Here we investigated possible transmission links by integrating epidemiological data and whole-genome sequencing of 25 infected HCWs and two HCWs in whom infection was highly suspected, as well as their family members who were successively infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the initial period in Wuhan Union Hospital. We also collected and analysed the clinical data of the 35 laboratory-confirmed cases among these individuals.

Methods

Study design and participants

A total of 35 laboratory-confirmed cases and two highly suspected cases were enrolled between 5 January and 12 February 2020, including 27 HCWs and 10 relatives out of seven families. All participants were interviewed using a standard questionnaire that elevated communicable diseases. Items such as HCWs' contact history with the confirmed COVID-19 patients, including where, when and how they had been exposed, were assessed. We mapped all cases with the precise time of symptom onset. Cluster outbreaks, potential exposures and possible patterns of transmission were estimated.

We collected clinical data from the 35 laboratory-confirmed cases, including symptoms and signs, laboratory examinations, chest imaging, comorbidities and complications, and clinical treatment and outcomes, which were arranged using a standardised data collection form, referencing the case record form shared by the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) [14] and the household transmission investigation protocol for SARS-CoV-2 infection from the World Health Organization (WHO) [15].

Real-time reverse transcription PCR assay to detect SARS-CoV-2

The SARS-CoV-2 laboratory test assays were based on the previous WHO recommendation [16]. RNA was extracted from oropharyngeal swabs of patients suspected of having SARS-CoV-2 infection using the respiratory sample RNA isolation kit. Then real-time reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) assay of SARS-CoV-2 RNA was conducted to amplify and test two target genes, including open reading frame 1ab (ORF1ab) and nucleocapsid protein (N). Details of the manufacturer's protocols for RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR assay, and the diagnostic criteria, are illustrated in the supplementary material.

Whole-genome sequencing and comparative genome analysis

Nasopharyngeal and/or oropharyngeal swabs were obtained from all COVID-19 cases for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid assay, and 22 were processed using whole-genome sequencing. Full genomes were sequenced using the BioelectronSeq 4000 (CapitalBio Corporation, Beijing, China) and assembled using the de novo genome assembler, SPAdes, version 3.10.1 [17]. The complete genome was annotated by Prokka, version 1.14.5 [18]. The mutations were analysed with the use of C-Sibelia, version 3.07 [19], based on the existing Wuhan-Hu-1 (NC_045512.2) genome, and were annotated by SnpEff, version 4.3 [20]. We integrated information from 60 published genomic sequences of SARS-CoV-2.

Full-length genomes were combined with published SARS-CoV-2 genomes and other coronaviruses and aligned using the FFT-NS-2 model by MAFFT, version 7.455 [21]. Maximum-likelihood phylogenies were inferred under a generalised-time-reversal (GTR)+ gamma substitution model and bootstrapped 1000 times to assess confidence using RAxML, version 8.2.12 [22]. The mutations of assembled amino acid sequences of Spike protein were compared with Wuhan-Hu-1 (NC_045512.2), bat-SL-CoVZC45 (MG772933.1) and SARS coronavirus isolate Tor2/FP1-10851 (JX163927.1) using Clustal Omega [23].

Epidemiological analysis

For participants with detailed onset information, a log-normal distribution was used to fit the incubation period, and the probability distribution of the incubation period was estimated. For participants with detailed medical visit information, the Weibull distribution was used to fit and determine onset-to-first-medical-visit and onset-to-admission distributions based on the dates of the onset of the illness, first medical visit and hospital admission. The clinical onset serial interval (COSI) was calculated, for which the probability distribution was estimated by the gamma distribution.

Statistical analysis

For clinical data, categorical variables were expressed as number (proportion). Continuous variables were expressed as medians and compared by Mann–Whitney U-tests. p-values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), unless otherwise indicated.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the institutional review board of the hospital, since we collected and analysed all data from the patients according to the policy for public health outbreak investigation of emerging infectious diseases issued by the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China.

Results

Nosocomial outbreak of COVID-19 pneumonia and its epidemiological transmission patterns

One male patient (aged 69 years) in the Department of Neurosurgery of Wuhan Union Hospital developed a fever of 38°C on 6 January 2020 and was finally diagnosed with COVID-19 on 16 January 2020. A female patient (aged 55 years) had a fever on 11 January 2020, and COVID-19 was confirmed on 18 January 2020. During this period, the HCWs in the Department of Neurosurgery either had direct contact with the two index patients without sufficiently efficient personal protective equipment, or they had indirect contact through their co-workers in the department gatherings on 12 and 13 January 2020. 12 of the HCWs in the Department of Neurosurgery were finally diagnosed with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 between 16 and 24 January 2020. Besides these, two HCWs (labelled as cases O and Z) were diagnosed as probable cases with similar clinical manifestations but negative viral nucleotide tests. Beyond the Department of Neurosurgery, there were 13 HCWs of other departments who were laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases. These departments also had suspects enrolled at the same time.

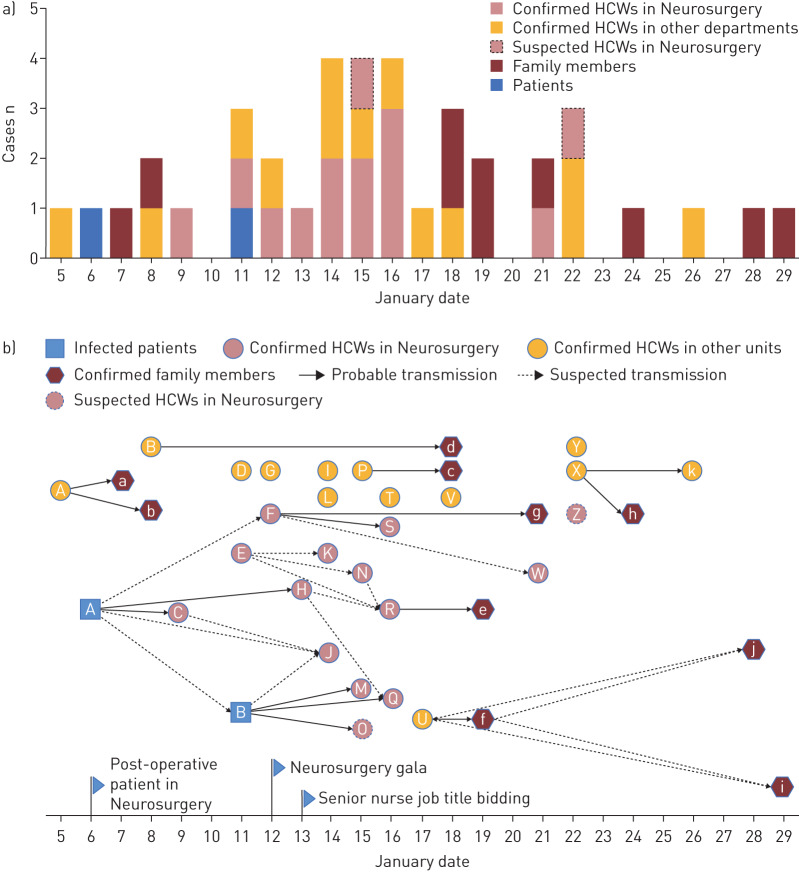

After the 25 HCWs' onset of illness, 10 out of 43 family members were confirmed as COVID-19 cases via nucleotide tests. The remaining 33 family members of the HCWs were not secondarily infected, due to the strict self-quarantine strategies taken by the HCWs immediately after their onset of illness, including wearing a facial mask when they came home, living alone in a separated room, never eating together with their families, etc. In summary, from 5 to 29 January 2020, 25 HCWs and 10 family members out of seven families were diagnosed with COVID-19 in a single hospital. The detailed epidemiological and contact history, as well as cluster information, are shown in the supplementary material. The time distribution of symptom onset and speculative transmission pattern are shown in figure 1a and b, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Transmission patterns. a) Timeline of onset of illness of 37 laboratory-confirmed and two suspected COVID-19 cases, including two laboratory-confirmed index patients admitted to the Department of Neurosurgery, 25 laboratory-confirmed healthcare workers (HCWs), 12 of whom were in the Department of Neurosurgery, 10 of their family members with COVID-19 and two HCWs highly suspected to have infection. b) Transmission map of two laboratory-confirmed index patients, 25 laboratory-confirmed HCWs, 10 of their family members with COVID-19 and two HCWs with suspected COVID-19. The letters represent the patient ID labels. In the Department of Neurosurgery, two gatherings were held: a department gala and a meeting among senior nurses, on 12 and 13 January 2020, respectively. There are nine clear transmission chains, as follows. Cluster 1: the first hospitalised man (index patient A) in the Department of Neurosurgery, with two nurses (C and H) who took care of him. Cluster 2: index patient B at the same ward as patient A, with three nurses (M, Q and O) who had close contact with patient B; nurse O, a probable case, had a negative viral nucleic acid test but had COVID-19-like symptoms and imaging findings. Cluster 3: nurse U with her mother-in-law f, her mother i and grandmother j. Cluster 4: nurse P with her husband c. Cluster 5: nurse F with her husband g, and her colleague (doctor S) who had close contact with F at the gala. Cluster 6: nurse R with her husband e. Cluster 7: nurse A with her husband a and daughter b. Cluster 8: nurse B with her boyfriend d; they had contact since 15 January. Cluster 9: doctor X with her mother h and father k who is a retired doctor. There are seven sporadic laboratory-confirmed cases: doctor D who was mainly responsible for gastroscopy; nurse G in the Department of Cardiology; nurse I in the Department of Cardiac Surgery; nurse V in the laboratory department, who is responsible for delivering clinical specimens daily; staff L in the finance department; doctor T, the director of a fever clinic; and doctor Y, in the Department of Neurology.

Transmission, incubation period and serial interval

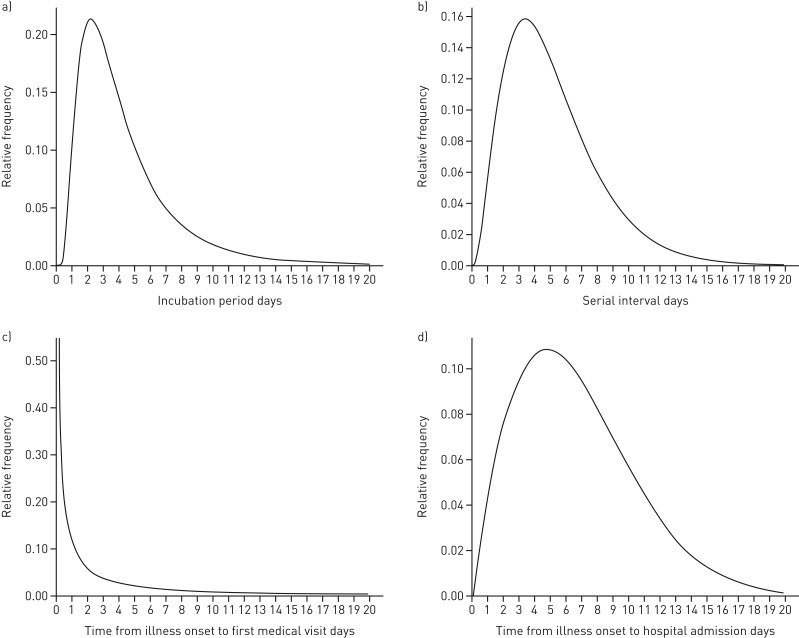

According to the information from 14 laboratory-confirmed cases who had specific dates of exposure and symptom onset, we estimated that the mean incubation period was 4.5 days (95% CI 3.0–6.4 days). The 95th percentile of the probability distribution for the incubation period was 11.4 days (95% CI 4.0–12.0 days) (figure 2a). Through the nine transmission chains (figure 1b), we estimated that the mean±sd of the COSI distribution was 5.2±3.2 days (95% CI 3.8–6.8 days) (figure 2b). Among the data obtained from the 35 confirmed cases (including the HCWs and their family members) and two suspected cases, the interval from the date of onset to the first medical visit was estimated to have a mean of 3.0 days (95% CI 2.2–3.9 days) (figure 2c). Of the 27 hospitalised cases (23 HCWs and four family members), the interval from the date of onset to hospital admission was estimated to have a mean of 6.6 days (95% CI 5.3–8.2 days) (figure 2d). There were no significant differences in these four indicators between HCWs and their family members.

FIGURE 2.

Typical statistical probability distribution. a) The estimated incubation period distribution. A log-normal distribution was used to fit the incubation period of the case and the probability distribution of the incubation period was estimated according to the information from 14 people who were confirmed COVID-19 cases and had clear dates of exposure and onset. b) The estimated serial interval. The probability distribution of the interval time was estimated using the gamma distribution through nine transmission chains (i.e. the time interval from onset of illness in one primary case to the onset of illness in the close contact case in a transmission chain). c) The estimated distribution of times from illness onset to first medical visit. The Weibull distribution was used to fit and estimate onset-to-first-medical-visit based on the dates of the onset of the illness and first medical visit of 35 laboratory-confirmed cases and two suspected cases. d) The estimated distribution of times from illness onset to hospital admission. The Weibull distribution was used to fit and estimate onset-to-admission distribution based on the dates of the onset of the illness and hospital admission of 27 hospitalised patients.

Demographic and clinical features in 35 confirmed cases

The clinical outcomes of the patients are shown in table 1. Among the 35 confirmed cases, 22 (62.9%) were women, and the median age was 37 years (range 25–88 years). A few patients had underlying diseases, including hypertension (11.4%), coronary heart disease (2.9%), diabetes (5.7%) and asthma (5.7%). By 12 February 2020, a total of 21 patients (60%) had recovered and been discharged from hospital, six patients (17.1%) requiring medical observation remained in hospital, and eight patients (22.9%) who stayed at home under self-quarantine had recovered. The median virus shedding time was 18.5 days (range 12–25 days). The median time for the length of hospital stay was 21 days (range 13–28 days).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics and clinical outcomes of healthcare workers (HCWs) and their family members with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia

| Variable | HCWs | Family members | Total |

| Patients n | 25 | 10 | 35 |

| Female | 17 (68) | 5 (50) | 22 (62.9) |

| Age years | 35 (25–63) | 52 (25–88) | 37 (25–88) |

| Age subgroup years | |||

| 0–15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16–44 | 20 (80) | 4 (40) | 24 (68.6) |

| 45–64 | 5 (20) | 5 (50) | 10 (28.6) |

| ≥65 | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (2.9) |

| Underlying illness | |||

| Hypertension | 3 (12) | 1 (10) | 4 (11.4) |

| Coronary heart disease | 0 | 1 (10) | 1 (2.9) |

| Diabetes | 1 (4) | 1 (10) | 2 (5.7) |

| Asthma | 2 (8) | 0 | 2 (5.7) |

| Exposure history | |||

| Huanan seafood wholesale market | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Confirmed patients | 7 (28) | 0 | 7 (20) |

| Confirmed HCWs | 3 (12) | 10 (100) | 13 (37.1) |

| Gala and meeting | 4 (16) | 0 | 4 (11.4) |

| Suspected patients | 3 (12) | 0 | 3 (8.6) |

| Unknown | 8 (32) | 0 | 8 (22.9) |

| Epidemiological data | |||

| Incubation period days | 4 (1–4) | 3 (2–12) | 3 (1–12) |

| Patients n | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Interquartile range | 1.75–4 | 2–9.5 | 2–5.25 |

| Interval from date of onset to first medical visit days | 2 (0–8) | 4 (0–13) | 2 (0–13) |

| Patients n | 25 | 10 | 35 |

| Interquartile range | 1–3.5 | 2–7 | 1–4 |

| Interval from date of onset to hospital admission days | 5 (3–16) | 11 (4–16) | 5 (3–16) |

| Patients n | 23 | 4 | 27 |

| Interquartile range | 3–7 | 4.75–15.75 | 3–10 |

| Serial interval days | 4 (3–7) | 3 (2–12) | 4 (2–12) |

| Patients n | 6 | 10 | 16 |

| Interquartile range | 3.75–5.5 | 2–10.25 | 3–8.5 |

| Management | |||

| Hospitalisation | 23 (92) | 4 (40) | 27 (77.1) |

| Home quarantine | 2 (8) | 6 (60) | 8 (22.9) |

| Clinical outcome at 12 February 2020 | |||

| Clinical amelioration, remained in hospital | 4 (16) | 2 (20) | 6 (17.1) |

| Recovered and discharged from hospital | 19 (76) | 2 (20) | 21 (60) |

| Home quarantine, recovered | 2 (8) | 6 (60) | 8 (22.9) |

| Length of stay in hospital days | 21 (15–28) | 13 (13–13) | 21 (13–28) |

| Interquartile range | 17–25 | 16.5–24.5 | |

| Virus shedding | |||

| Virus shedding negative | 20 (80) | 20 (57.1) | |

| Virus shedding time days | 18.5 (12–25) | 18.5 (12–25) | |

| Interquartile range | 14.25–21.75 | 14.25–21.75 |

Data are presented as n (%) or median (range), unless otherwise stated.

The most common signs and symptoms on admission were fever (85.7%) and malaise (74.3%); 22 patients (62.9%) had a poor appetite, and 19 patients (54.3%) had a cough. Six patients received oxygen therapy because of hypoxaemia. Corticosteroids were not administrated in any patients (supplementary table S1).

The laboratory results of the patients are shown in supplementary table S2. The complete blood counts of patients on admission showed that the number of white blood cells was normal in most patients (27 out of 31; 87.1%). Out of 30 patients, 13 (43.3%) had lymphopenia. Alanine aminotransferase was abnormal in four patients (15.4%). Creatinine was normal in all patients. Seven patients (30.4%) had increased lactate dehydrogenase.

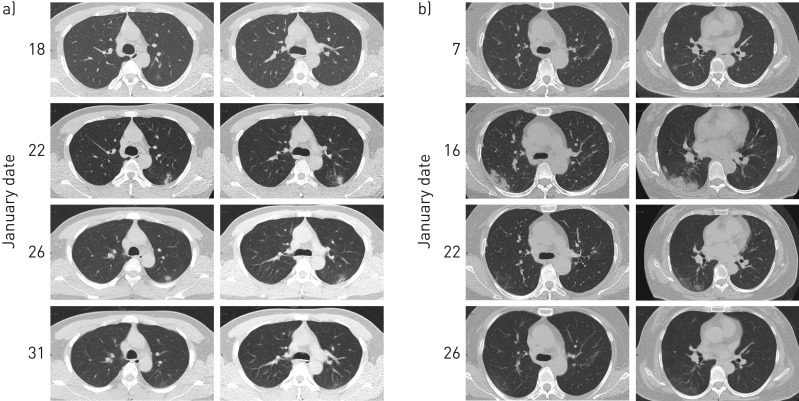

On admission, infiltrations in chest computed tomography (CT) images were detected in most cases. In total, 29 (82.9%) showed ground-glass opacities, four (11.4%) showed consolidations, and one (2.9%) presented mixed ground-glass opacities and consolidation. Only one patient (2.9%) had normal chest imaging (supplementary table S2). Figure 3 shows two series of typical CT images of moderate pneumonia (HCWs A and C) and supplementary figure S5 shows a series of CT images from a suspected case (HCW O).

FIGURE 3.

Computed tomography (CT) images from two healthcare workers (A and C), showing moderate typical pneumonia. a) The CT images of patient C showed a lesion in the posterior segment of the left superior lobe. Early on, the range of lesions gradually expanded, from a light ground-glass opacity (GGO) to mixed with consolidation and, at last, the lesions were significantly reduced, 17 days after onset of illness, leaving only a thin GGO under the pleura on 31 January, 22 days after onset of illness. b) The CT images of patient A showed pneumonia in both lower lungs, which was more prominent in the lower right lung. The condition gradually worsened from 7 to 16 January, but on 22 January, 17 days after onset of illness, the GGO became alleviated and resolved significantly on 26 January, 21 days after onset of illness.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

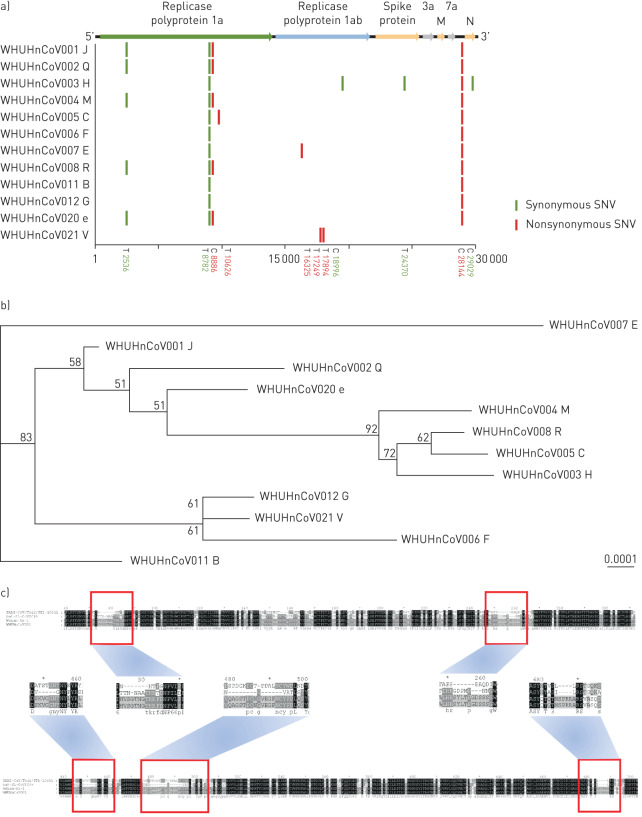

We obtained 12 whole-genome sequences (GenBank accession numbers MT079843–MT079854) after implementing de novo sequencing from 22 swab specimens from 22 COVID-19 patients. These 12 whole-genome sequences were from patients B, C, E, F, G, H, J, M, Q, R, V and e, as labelled in figure 1b, and their corresponding sample numbers are summarised in supplementary table S3. The remaining 10 samples were removed due to insufficient coverage of the extracted virus genome. Compared with Wuhan-Hu-1, except for V, the remaining 11 viral genomes all had two nucleotide mutations. We found that these two mutation sites both exist in 16 (26.2%) published virus genomes (supplementary tables S4–S6). V showed two missense mutations completely different from the other 11 cases; V was a nurse in the laboratory department, responsible for delivering clinical specimens, so we assume that the difference in virus sequence may be because he was exposed to many other patients' clinical specimens due to his job. The sequences from R and her husband e are the same (figure 4a). A total of six missense mutations were found in the 12 genomes of SARS-CoV-2 strains, but none of them were located in the genes for structural proteins in the new coronavirus, including S, E, M or N proteins (figure 4a). Five of the mutations were located on the nonstructural proteins, which are hydrolysed from the virus-encoded polyproteins 1a/1ab1. The one remaining missense mutation (position 28 144, T>C) was located on the cofactor gene ORF8.

FIGURE 4.

Sequencing analysis of the sequences of 12 COVID-19 cases. WHUHnCoV001–WHUHnCoV008, WHUHnCoV011, WHUHnCoV012, WHUHnCoV0020 and WHUHnCoV021 are the sample IDs. The letters following them represent the corresponding patient IDs from figure 1b. a) Full-genome structure and mutation information compared with Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank accession number NC_0455122). Nucleotide differences are shown by vertical coloured bars in the 12 full-genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2 obtained from our cases. Green indicates a synonymous single-nucleotide variant (SNV) in the query sequence, red a nonsynonymous SNV. b) Phylogenetic tree of full-length genomes of SARS-CoV-2 from our 12 samples. The number next to each node represents a measure of support for the node, given as a percentage, where 100 represents maximal support. The scale bar shows the length of branch that represents an amount of genetic change of 0.0001. Sequences from six healthcare workers (C, H, J, M, Q and R) in the Department of Neurosurgery and one family member (e) were closely related in the phylogenetic tree. The obviously separate clade was from healthcare worker B in the Department of Gynaecology. c) Mutations in Spike protein of WHUHnCoV001 (healthcare worker J). The reference Spike proteins were from SARS coronavirus isolate Tor2/FP1-10851 (JX163927.1), bat-SL-CoVZC45 (MG772933.1) and Wuhan-Hu-1 (NC_045512.2). Compared with bat-SL-CoVZC45 and SARS coronavirus isolate Tor2/FP1-10851, SARS-CoV-2 had four insertion regions (positions 257–261, 449–454, 479–495 and 685–690) and three insertion regions (positions 74–85, 252–259 and 685–690), respectively.

The phylogenetic tree of full-length genomes showed that SARS-CoV-2 strains form a monophyletic clade with a bootstrap support of 100% (supplementary figure S3). The most closely related sequence to this clade is bat-SL-CoV. Sequences from six HCWs (C, H, J, M, Q and R) in the Department of Neurosurgery and one family member (e) were closely related in the phylogenetic tree (figure 4b). The sequence from HCW B in another department formed a separate lineage. Compared with bat-SL-CoVZC45 (MG772933.1) and SARS coronavirus isolate Tor2/FP1-10851 (JX163927.1), SARS-CoV-2 had four and three insertion regions respectively (figure 4c).

Discussion

At the very early stage of the outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan City and Hubei Province in China, we lacked efficient viral identification capacity to diagnose probable COVID-19 cases. There were no effective prevention measures in general hospital settings to isolate and manage the suspected COVID-19 cases, or valid containment measures to block the transmission pathways [12]. HCWs are the highest risk occupational population in outbreaks of such acute respiratory infectious diseases, such as SARS and COVID-19, which are transmitted by contact or respiratory droplets, aerosols or fomites [24]. Here, we have described several clusters of COVID-19 cases in a hospital, showing person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2, and have assessed the epidemiological features of COVID-19.

We have reported 25 laboratory-confirmed cases and two highly suspected cases among HCWs, who were infected successively in Wuhan Union Hospital. Of these, 14 were co-workers in the Department of Neurosurgery. They formed two clusters, with two index patients as the sources, which further emphasised the importance of adequate protection for HCWs during their daily work. Moreover, seven family clusters associated with these HCWs have occurred, mainly due to the close contact between the affected HCWs and their family members without any isolation measures. Fortunately, the majority of HCWs, who isolated themselves from their family members at the onset of illness, effectively protected their family members from getting infected. Through mapping the time of onset and possible routes of transmission (figure 1b), we can conclude that the general hospitals are just like an epidemic hub, gathering a lot of patients who are the sources of infection, which would efficiently facilitate and exacerbate the transmission and spreading of virus via public transport or alternative ways.

Through phylogenetic analysis, we found clustered cases that were closer in the phylogenetic tree (figure 4b). Mutation analysis showed that the sequence from each sample had different mutation sites, most of which were synonymous mutations. Although some missense mutations existed, none of them were located in the genes for structural proteins of SARS-CoV-2 (figure 4a). Additionally, the amino acid sequences of the structural proteins had no changes (supplementary figures S1 and S2).

Most of the initial symptoms in our cases were myalgia, malaise and fever. Some patients had no fever but only mild symptoms such as nasal congestion, which may have led to patients being overlooked, causing a wider spread of COVID-19. In our cases, the intervals of onset of illness to first medical visit and onset of illness to hospital admission were estimated to have a mean of 3.0 days and 6.6 days, respectively, which were shorter than in other studies [25]. By 12 February, 21 out of 27 hospitalised cases (77.8%) had recovered and were discharged; none of them were admitted to the intensive care unit or had died. From the chest CT images from HCWs A and C, very mild or moderate infiltrations were presented, and these became alleviated and resolved significantly in a short time (figure 3). Thus, early diagnosis, isolation and timely treatments can speed up the recovery of patients and decrease the deteriorative tendency.

The median time for virus shedding to become negative in our cases was a long period of 18.5 days (range 12–25 days). It is worth mentioning that nurse F suffered severe diarrhoea during hospitalisation. Even after the nucleic acid test of nasopharyngeal swabs turned negative and lung CT images got better, the viral nucleic acid test of the stool maintained a sustainable positive result, 1 month after onset. We must thus pay close attention to the status of virus clearance of patients with COVID-19. Such a long virus shedding period perhaps highlights the production of efficiently neutralising antibodies in a comparatively postponed manner or even an unsatisfactory titre in the patient's plasma. Therefore, it might be necessary to extend the period of hospitalisation for infectious control purposes, and we should adopt a prudent strategy for treating critically severe patients with convalescent plasma from COVID-19 patients.

Our current study has some limitations. First, only 37 patients were enrolled, which might have led to potential bias of the incubation period and COSI in our study. More accurate calculation of incubation period and COSI would be possible with a larger sample size. Secondly, the investigation of the kinetics of virus shedding and the relevant viral loading in both respiratory and intestinal tracts was not possible, since the novel causative pathogen has only just been identified. Thirdly, the potential for superficial exposure in infection transmission was not investigated, which may need further studies. Fourthly, the kinetics of viral antibodies, especially neutralised antibodies, were not monitored due to laboratory limitations. Finally, viral genome analysis and traceability from each patient have not been performed and should be conducted in future studies.

In summary, similar to the 2003 SARS outbreak in Guangzhou, the current epidemic of SARS-CoV-2 resulting in COVID-19 in Wuhan is mainly due to efficient person-to-person transmission or super-spreading events in hospital settings and social activities, based on the short period of incubation and COSI. Practical strategies and measures, such as isolation of patients, tracing and quarantine of close contacts and containment of severe epidemic areas, are crucial to block the spread. Earlier detection and diagnosis of patients with COVID-19 will result in better prognoses.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-00544-2020.Supplement (1.3MB, pdf)

Shareable PDF

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate both the International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC) for sharing data collection templates publicly on the website and the World Health Organization for sharing the household transmission investigation protocol for the SARS-CoV-2 infection. We would like to dedicate this article and pay the highest tribute to every brave healthcare worker who is fighting, devoting themselves and self-sacrificing to control the outbreak of the novel coronavirus pneumonia.

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

Author contributions: Z. Gao and W-L. Ma had the idea for and designed the study, had full access to all data, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. X. Wang, Y. He, L. Liu and X. Ma contributed to drafting the manuscript. Z. Gao, X. Wang, Y. Zheng, Q. Zhou, H. Shi and W-L. Ma contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for valuable intellectual content. Y. He, L. Liu, L. Liang and X. Ma conducted the statistical analysis. T. Deng, Y. Gao, B. Zhai, W. Liu, X. Bai, T. Pan, G. Wang, Y. Chang and Z. Zhang contributed to the sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. X. Wang, Q. Zhou, X. Wei, Nanchuan Jiang, L. Ma, D. Yang, J. Zhang, B. Yang, Y. Xu and Ning Jiang contributed to data acquisition, data analysis or data interpretation. The final version had been reviewed and approved by all authors.

Conflict of interest: X. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Q. Zhou has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. He has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Liu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Ma has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Wei has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N. Jiang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Liang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Zheng has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L. Ma has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Xu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: D. Yang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: J. Zhang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Yang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N. Jiang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Deng has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Zhai has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Gao has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: W. Liu has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: X. Bai has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: T. Pan has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: G. Wang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Y. Chang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Z. Zhang has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H. Shi has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: W-L. Ma has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: Z. Gao has nothing to disclose.

Support statement: This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81500005, 81973990, 91643101, 81900133), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant 2020kfyXGYJ034) and the National Science and Technology Major Project (grant 2017ZX10103004–006). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drosten C, Günther S, Preiser W, et al. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China Update on new coronavirus pneumonia epidemic as of 24:00 on April 7. www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/yqfkdt/202004/5e2b6f0bd47d48559582242e3878447d.shtml Date last updated: 8 April 2020. Date last accessed: 8 April 2020.

- 5.Johns Hopkins University Center for Systems Science and Engineering COVID-19 global cases. https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6 Date last accessed: 8 April 2020.

- 6.Carinci F. Covid-19: preparedness, decentralisation, and the hunt for patient zero. BMJ 2020; 368: bmj.m799. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet 2020; 395: 507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 2020; 323: 1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020; 579: 270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu JT, Leung K, Leung GM. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet 2020; 395: 689–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao ZC. [Efficient management of novel coronavirus pneumonia by efficient prevention and control in scientific manner]. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020; 43: 163–166. doi: 10.3760/cma.issn.1001-0939.2020.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China State Council's Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism for New Coronavirus Infected Pneumonia introduce the latest progress of epidemic prevention and control, especially the measures of caring for medical staff. www.nhc.gov.cn/xwzb/webcontrollerdo?titleSeq=11231&gecstype=1 Date last updated: 26 March 2020. Date last accessed: 26 March 2020.

- 14.International Severe Acute Respiratory and emerging Infection Consortium COVID-19 Case Record Forms (CRF). https://isaric.tghn.org/novel-coronavirus/ Date last updated: 26 March 2020. Date last accessed: 26 March 2020.

- 15.World Health Organization Household transmission investigation protocol for 2019-novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection. www.who.int/publications-detail/household-transmission-investigation-protocol-for-2019-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-infection Date last updated: 25 January 2020. Date last accessed: 26 March 2020.

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Real-time RT-PCR panel for detection of 2019-novel coronavirus. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-detection-instructions.html#rRT-PCR-assays Date last updated: 26 March 2020. Date last accessed: 26 March 2020.

- 17.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 2012; 19: 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minkin I, Pham H, Starostina E, et al. C-Sibelia: an easy-to-use and highly accurate tool for bacterial genome comparison. F1000Res 2013; 2: 258. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.2-258.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang le L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly 2012; 6: 80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform 2019; 20: 1160–1166. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.European Molecular Biology Laboratory European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) Clustal Omega. www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/ Date last accessed: 26 March 2020.

- 24.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1199–1207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material ERJ-00544-2020.Supplement (1.3MB, pdf)

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-00544-2020.Shareable (378KB, pdf)