Since the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, most attention has focused on containing transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and addressing the surge of critically ill patients in acute care settings. Indeed, as of 29 April 2020, over 3 million confirmed cases have been accounted for globally [1]. In the coming weeks and months, emphasis will gradually involve also post-acute care of COVID-19 survivors. It is anticipated that COVID-19 may have a major impact on physical, cognitive, mental and social health status, also in patients with mild disease presentation [2]. Previous outbreaks of coronaviruses have been associated with persistent pulmonary function impairment, muscle weakness, pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, vocational problems, and reduced quality of life to various degrees [3–5].

Short abstract

An ordinal tool is proposed to measure the full spectrum of functional outcomes following COVID-19. This “Post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) scale” can be used for tracking functional status over time as well as for research purposes. https://bit.ly/3cofGaa

To the Editor:

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, most attention has focused on containing transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and addressing the surge of critically ill patients in acute care settings. Indeed, as of 29 April 2020, over 3 million confirmed cases have been accounted for globally [1]. In the coming weeks and months, emphasis will gradually involve also post-acute care of COVID-19 survivors. It is anticipated that COVID-19 may have a major impact on physical, cognitive, mental and social health status, also in patients with mild disease presentation [2]. Previous outbreaks of coronaviruses have been associated with persistent pulmonary function impairment, muscle weakness, pain, fatigue, depression, anxiety, vocational problems, and reduced quality of life to various degrees [3–5].

Given the heterogeneity of COVID-19 in terms of clinical and radiological presentation, it is pivotal to have a simple tool to monitor the course of symptoms and the impact of symptoms on the functional status of patients, i.e. a scale that can measure the consequence of the disease beyond binary outcomes such as mortality. In view of the massive number of COVID-19 survivors that require follow-up, an easy and reproducible instrument to identify those patients suffering from slow or incomplete recovery would help in guiding considered use of medical resources and will also standardise research efforts.

The optimal instrument for this purpose is an ordinal scale assessing the full range of functional limitations to capture the heterogeneity of post-COVID-19 outcomes. Ordinal scales rank patients in meaningful categories and do not differentiate between underlying causes to be of general value. These scales can be used to track improvement over time and answer meaningful clinical questions (e.g. “How will I come out of this corona infection?”) or for research purposes. They may be either self-reported or assessed in a formal standardised interview [6].

Recently, our group proposed an ordinal scale for assessment of patient-relevant functional limitations following an episode of venous thromboembolism (VTE): the post-VTE functional status (PVFS) scale [7, 8]. It covers the full spectrum of functional outcomes, and focuses on both limitations in usual duties/activities and changes in lifestyle in six scale grades. In short, grade 0 reflects the absence of any functional limitation, and the death of a patient is recorded in grade D. From grade 1 upwards, symptoms, pain or anxiety are present to an increasing degree. This has no effect on activities for patients in grade 1, whereas a lower intensity of the activities is required for those in grade 2. Grade 3 accounts for inability to perform certain activities, forcing patients to structurally modify these. Finally, grade 4 is reserved for those patients with severe functional limitations requiring assistance with activities of daily living. This scale was developed after discussion with international experts (via a Delphi analysis) with input from patients (via patient focus groups). The inter-observer agreement of scale grade assignment was shown to be good-to-excellent with kappas of 0.75 (95% CI 0.58–1.0) and 1.0 (95% CI 0.83–1.0) between self-reported values and independent raters, respectively [7].

The idea of using ordinal scales for COVID-19 research is not new. The World Health Organization proposed the “Ordinal Scale for Clinical Improvement” on 18 February 2020 [9], with categories mainly based on the type of treatment, to be used as the primary end-point in acute-phase trials (e.g. NCT04292899 and NCT04351724). However, due to its focus on in-hospital treatment, this scale is not a useful measure of the long-term outcomes of COVID-19 and its treatment after discharge.

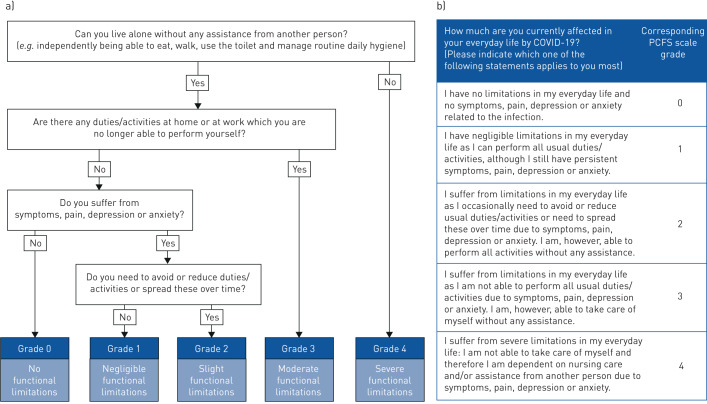

There is a high incidence of pulmonary embolism itself, alongside myocardial damage/myocarditis and neurological complications, in critically ill patients with COVID-19 [10, 11]. Therefore, we consider our PVFS scale (after slight adaptation) to be useful in the current COVID-19 pandemic too (figure 1). The proposed “Post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) scale” could be assessed upon discharge from the hospital, at 4 and 8 weeks post-discharge to monitor direct recovery, and at 6 months to assess functional sequelae. We have implemented the scale in our own clinical practices in Leiden University Medical Center and Kantonsspital Winterthur, and are planning to incorporate it in the LEOSS registry (Lean European Open Survey on SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients; https://LEOSS.net) and Maastricht University Medical Center. Notably, the scale is not meant to replace other relevant instruments for measuring quality of life, tiredness or dyspnoea in the acute phase, but to be used as an additional outcome measure to evaluate the ultimate consequences of COVID-19 on functional status. We acknowledge that this “PCFS scale” is currently not validated, and its usefulness will depend on the local conditions under which it is implemented. However, if implemented alongside existing outcomes, we will be able to generate sufficient evidence to make formal conclusions on its use to guide post-COVID-19 care.

FIGURE 1.

Patient self-report methods for the Post-COVID-19 Functional Status (PCFS) scale. a) Flowchart. b) Patient questionnaire. Instructions for use: 1) to assess recovery after the SARS-CoV-2 infection, this PCFS scale covers the entire range of functional limitations, including changes in lifestyle, sports and social activities; 2) assignment of a PCFS scale grade concerns the average situation of the past week (exception: when assessed at discharge, it concerns the situation of the day of discharge); 3) symptoms include (but are not limited to) dyspnoea, pain, fatigue, muscle weakness, memory loss, depression and anxiety; 4) in case two grades seem to be appropriate, always choose the highest grade with the most limitations; 5) measuring functional status before the infection is optional; 6) alternatively to this flowchart and patient questionnaire, an extensive structured interview is available. The full manual for patients and physicians or study personnel is available from https://osf.io/qgpdv/ (free of charge).

This correspondence is a call for action to use and validate ordinal scales such as the one proposed by us for determining functional recovery from COVID-19. The full manual for patients and physicians or study personnel is available from https://osf.io/qgpdv/ (free of charge).

Shareable PDF

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author contributions: F.A. Klok, G.J.A.M. Boon and B. Siegerink drafted the first version of the manuscript. All authors revised the review critically for important intellectual content and provided final approval for submission.

Conflict of interest: F.A. Klok reports grants from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Actelion, the Netherlands Thrombosis Foundation and the Dutch Heart Foundation, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: G.J.A.M. Boon has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Barco has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Endres reports grants from DFG under Germany's Excellence Strategy (EXC-2049; 390688087) and Bayer, and personal fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Amgen, GSK, Sanofi, Covidien, Novartis and Pfizer, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: J.J.M. Geelhoed has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S. Knauss has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: S.A. Rezek has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M.A. Spruit reports grants from the Netherlands Lung Foundation and Stichting Astma Bestrijding, and grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: J. Vehreschild has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: B. Siegerink has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/ Date last accessed: April 2020.

- 2.Simpson R, Robinson L. Rehabilitation after critical illness in people with COVID-19 infection. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2020; 99: 470–474. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0000000000001443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ngai JC, Ko FW, Ng SS, et al. The long-term impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on pulmonary function, exercise capacity and health status. Respirology 2010; 15: 543–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01720.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tansey CM, Louie M, Loeb M, et al. One-year outcomes and health care utilization in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 1312–1320. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neufeld KJ, Leoutsakos J-MS, Yan H, et al. Fatigue symptoms during the first year following ARDS. Chest 2020; in press [ 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.059]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegerink B, Rohmann JL. Impact of your results: beyond the relative risk. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2018; 2: 653–657. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boon GJAM, Barco S, Bertoletti L, et al. Measuring functional limitations after venous thromboembolism: optimization of the post-VTE functional status (PVFS) scale. Thromb Res 2020; 190: 45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klok FA, Barco S, Siegerink B. Measuring functional limitations after venous thromboembolism: a call to action. Thromb Res 2019; 178: 59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/COVID-19_Treatment_Trial_Design_Master_Protocol_synopsis_Final_18022020.pdf WHO R&D Blueprint. Novel Coronavirus: COVID-19 Therapeutic Trial Synopsis. Draft February 18, 2020.

- 10.Lodigiani C, Iapichino G, Carenzo L, et al. Venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 patients admitted to an academic hospital in Milan, Italy. Thromb Res 2020; 191: 9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020; 191: 145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This one-page PDF can be shared freely online.

Shareable PDF ERJ-01494-2020.Shareable (727.2KB, pdf)