Abstract

Neuropsychiatric disorders are the leading cause of mental and intellectual disabilities worldwide. Current therapies against neuropsychiatric disorders are very limited, and very little is known about the onset and development of these diseases, and their most effective treatments. MIR137 has been previously identified as a risk gene for the etiology of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism spectrum disorder. Here we generated a forebrain-specific MIR137 knockout mouse model, and provided evidence that loss of miR-137 resulted in impaired homeostasis of potassium in mouse hippocampal neurons. KCC2, a potassium-chloride co-transporter, was a direct downstream target of miR-137. The KCC2 specific antagonist VU0240551 could balance the current of potassium in miR-137 knockout neurons, and knockdown of KCC2 could ameliorate anxiety-like behavior in MIR137 cKO mice. These data suggest that KCC2 antagonists or knockdown might be beneficial to neuropsychiatric disorders due to the deficiency of miR-137.

Keywords: MIR137, KCC2, Anxiety, Potassium

INTRODUCTION

Neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, autism, depression, and anxiety, are very common all around the world [1]. The limited effectiveness of current therapies against neuropsychiatric disorders and neurological disorders highlights the urgent need for understanding their pathological mechanisms and for developing new approaches to prevent or retard the disease progression [2].

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified MIR137 (encoding microRNA-137) as a risk gene for the etiology of schizophrenia [3], bipolar disorder [4], and autism spectrum disorders [5]. MIR137 is a key regulator in neurodevelopment, with deletion of Mir137 in the germline or nervous system resulting in embryonic or postnatal lethality [6]. Growing evidence supports the idea that microRNA-137 (miR-137) is a critical epigenetic modulator in neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and synaptic plasticity [7-10]. Only a few important target genes of miR-137 that might be responsible for neuropsychiatric dysfunction, such as BDNF, CACNA1C, EZH2, PDE10A, TCF4, and ZNF804A, have been experimentally validated [11, 12].

Neural activity depends on electric signals that are transmitted from the presynaptic neuron to the postsynaptic cell via chemical signaling. The positive or negative change in membrane potential of the postsynaptic neuron is caused by the activation of postsynaptic receptors, which are ion channels whose activation alters permeability for specific ions [13]. Although genetic variation in genes coding for ion channels increases risk for psychiatric disorders [14-17], little is known about the function of miR-137 on ion channels in neurons.

In this study, we provide the first evidence that loss of miR-137 results in impaired homeostasis of potassium in neurons, both in vitro and in vivo. KCC2 (Slc12a5), a potassium-chloride co-transporter, was significantly upregulated in miR-137 knockout neurons. Importantly, VU0240551, a specific KCC2 antagonist [18], can maintain the homeostasis of potassium in MIR137 knockout neurons. Moreover, knockdown of KCC2 could rescue anxiety-like phenotype in MIR137 cKO mice. These results suggest that miR-137 loss of function contributes to potassium efflux via KCC2, and targeting the miR-137-KCC2 pathway might have great therapeutic potential for treating neuropsychiatric disorders due to the deficiency of miR-137.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All experiments involving animals were performed in accordance with the animal protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Mice were housed in groups of 3~5 animals under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle, and were fed ad libitum on a standard mouse diet. The miR-137f/f mice were generated as previously described [10]. The Emx1-Cre transgenic mice were bought from Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 005628). The miR-137 conditional knockout mice were generated by breeding miR-137f/f mice with Emx1-Cre transgenic mice, as described previously [19].

Primary hippocampal neuron culture

Hippocampal neurons were isolated from P0 MIR137 cKO and WT mice, and cultured on plates (1×104 cells per well in a 24-well plate) coated with poly-D-lysine (100 µg/ml). The dissected hippocampus tissue was digested with trypsin-EDTA for 10 min at 37°C. The tissue was then washed three times with MEM containing 10% FBS. Hippocampal neurons were then dissociated with the culture medium. Then neurons were grown in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2% B27 (Invitrogen), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen), and penicillin/streptomycin.

Dual luciferase assays

Approximately 300 base pairs around the predicted target site from the KCC2 3’UTR was cloned into the pIS2 vector using the XhoI and NotI restriction sites in the multiple cloning region downstream of the luciferase reporter gene. Mutagenesis of the binding site on KCC2 3’UTR was performed using the QuickChange II Site-directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. All plasmid clones were then verified by sequencing.

Dual luciferase transfection assays were performed as previously described [20, 21]. In brief, HEK293 cells in 24-well plates were transfected with sh-miR-137 (pCR2.1 TOPO vector) and pIS2-3’UTR or mutated pIS2-3’UTR using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Meanwhile, pIS2 vector with no 3’UTR was cotranfected with U6-neg-shRNA (pCR2.1 TOPO vector) or sh-miR-137 to set up as a control. All Luciferase readings were recorded using Dual-Luciferase Reporter 1000 System (Promega) following manufacturer's instructions.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings were carried out using an Axopatch 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). The pClamp10.6 software was used for data acquisition and analysis. Patch pipettes (6~10 MΩ) were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries with a micropipette puller (Sutter instrument, USA). The internal pipette solution contained (in mM): 135 K-gluconate, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 0.3 MgGTP, and 0.5 Na2ATP (pH 7.3 with KOH). The membrane potential was held at -65 mV. Series resistances and cell capacitance compensation were carried out prior to recording. The recordings were included only in those with high resistance seal (>1 GΩ) and a series resistance <25 MΩ.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from hippocampus tissue or cultured neurons using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Two micrograms of total RNA were reverse transcribed with either oligo (dT) primers or specific primers by a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). For qRT-PCR analysis, 25 ng of cDNA and 0.5 µM primers were used in a final volume of 20 µl according to the manufacturer’s instructions (SYBR Green Master, Roche). Each reaction was run in triplicate and analyzed following the △△CT method using U6 or GAPDH as a normalization control. The following primers are used: KCC2 (forward: 5’-GGGCAGAGAGTACGATGGC-3’; reverse: 5’-TGGGGTAGGTTGGTGTAGTTG-3’), GAPDH (forward: 5’-AAGGTCATCCCAGAGCTGAA-3’; reverse: 5’-AGGAGACAACCTGGTCCTCA-3’).

Protein quantification

Hippocampal tissues or cultured neurons were lysed in a buffer containing 25 mM HEPES at pH7.9, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP40, and proteinase inhibitor cocktails (Roche). Protein concentrations were determined by Folin phenol method with bovine serum albumin as protein standard. Twenty micrograms of protein were separated on 8~12% SDS-PAGE gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were then blocked in 5% BSA in TBS-T with 0.05% Tween-20, and incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnights. Dilutions of primary antibodies were 1:1,000 for KCC2 (Millipore, #07–432), and 1:10,000 for β-actin antibody (Sigma). As for the secondary antibodies, we used HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit at 1:500. Enhanced chemo luminescence (ECL, Pierce) was used for detection. Quantifications of Western blots were determined using Quantity One V4.4.0 (BioRad).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with cold PBS, followed by 4% PFA in PBS (pH 7.4). Brain tissue was dissected out, equilibrated in 30% sucrose, and sectioned into 40 µm-thick sections. The brain sections were washed in PBS for 15 min three times, and then blocked in a blocking solution (3% BSA, 0.3%Triton X-100, 0.2% sodium azide) at room temperature for 1 h. The primary antibodies we used were as follows: anti-KCC2 (1:1,000, Millipore, #07–432), anti-Map2 (1:1,000, Millipore, Mab3418). After overnight incubation with primary antibody at 4°C, the brain sections were washed with TBS for 30 min three times and then incubated with the secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594 (1:500). Sections were finally stained with DAPI and mounted on glass-slides using adhesion anti-fade medium.

Lentivirus production and in vivo grafting

KCC2 shRNA sequence (CUACGAGAA GACAUUAGUA) [22] was inserted in the U6-shRNA lentiviral construct. Lenti-sh-KCC2 and lenti-sh-Neg (negative control) viruses were produced with titers at a range around 1×109 TU/ml as described previously [23, 24]. Lentivirus was grafted stereotaxically into the hippocampus of 8-week-old male MIR137 WT and cKO mice as described by Heldt et al. [25].

Behavioral tests

Mice were kept in groups of 4~5 animals on a 12:12 h light:dark cycle. The open field test and the light-dark preference test were performed during the light phase at week 3 after lentiviral injection as previously described [19]. Videos were recorded and analyzed by the software Smart V3.0.03 (Panlab, Barcelona, Spain).

Statistical analyses

Either unpaired Student’s two-tailed t tests or ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics V26 software. Samples sizes were provided in each figure legend. All data were presented as mean±SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

RESULTS

Loss of miR-137 impairs the homeostasis of potassium in primary hippocampal neurons

We originally generated miR-137 conditional knockout mice that displayed dysregulated synaptic plasticity, repetitive behavior, anxiety-like behavior, and impaired learning and social behavior [10]. Since neurological and neuropsychological diseases are pathophysiologically linked to potassium channel dysfunction [26, 27], we speculated that loss of miR-137 may play a role in regulating K+ currents and thus result in neurodysfunction.

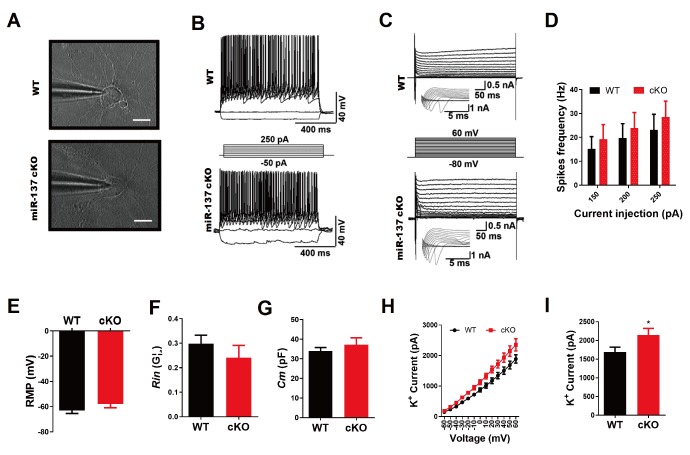

To examine the electrophysiological properties of primary hippocampal neurons isolated from MIR137 cKO and WT mice, we performed whole-cell patch-clamp recording of the electrical activity of neurons at 14 days in culture (Fig. 1A). We found that all primary hippocampal neurons elicited multiple action potentials upon the injection of depolarizing currents (Fig. 1B) (WT, n=9; cKO, n=10) and large fast-inactivating inward currents followed by outward potassium currents when evoked by a series of voltage steps (Fig. 1C) (WT, n=12; cKO, n=13). We observed no significant difference in spike frequency of action potential (Fig. 1D, resting membrane potential (RMP) (Fig. 1E), membrane resistance (Rin) (Fig. 1F), and membrane capacitance (Cm) (Fig. 1G) between MIR137 cKO and WT neurons. However, the peak of the voltage-gated K+ current was significantly higher in MIR137 cKO neurons (Fig. 1H and 1I). These data indicate that the deletion of MIR137 impairs the homeostasis of potassium in hippocampal neurons.

Fig. 1.

MiR-137 deficiency impairs K+ efflux of potassium in primary mouse hippocampal neurons. (A) Phase-contrast images of primary mouse hippocampal neurons during patch clamp recordings at DIV 14. (B) Representative traces of action potentials in response to step current injections in primary mouse hippocampal neurons at DIV 14. Membrane potential was maintained at approximately -40 mV. Step currents were injected from -50 pA to +250 pA in 50 pA increments (middle panel). All neurons elicited multiple action potentials upon the injection of depolarizing currents. (C) Representative traces of whole-cell currents in voltage-clamp mode. Primary neurons from MIR137 WT or cKO mice were held at -70 mV. Step depolarization from -80 mV to +60 mV at 10-mV intervals was delivered (middle panel). Insets were respective traces on an expanded scale. (D) Characterization of action potentials generation properties in terms of spikes frequency with current-pulse amplitude, recorded from primary mouse hippocampal neurons of MIR137 WT or cKO mice (n=12 and 9, respectively). (E~G) Statistics of intrinsic membrane properties of MIR137 WT and cKO neurons (n =14 and 9, respectively). RMP, resting membrane potential (E); Rin, membrane input resistance (F); Cm, capacitance (G). (H) The relationship between voltage and K+ current (WT, n=12; cKO, n=8). (I) The peak amplitude of K+ current was elevated in MIR137 cKO neurons. *p<0.05.

K+–Cl- cotransporter 2 (KCC2) is a direct downstream target of miR-137

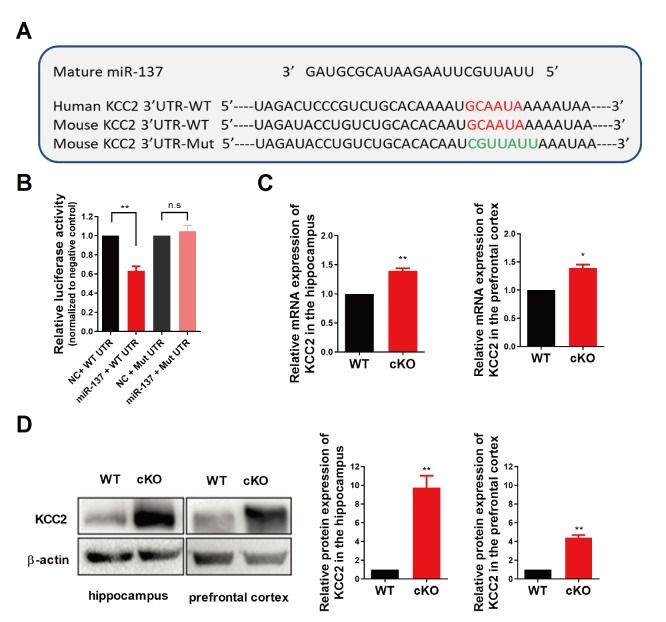

To get more insight into the molecular mechanism underlying the effect of miR-137 loss-of-function on voltage-gated K+ current, we performed a combined computational and experimental study to identify the downstream targets of miR-137 in the brain. We first used the TargetScan program to predict mRNA targets [28]. TargetScan analysis identified 15 potassium channel associated targets predicted to be responsive to miR-137 and conserved among species. Among these candidate targets, the K+–Cl- cotransporter 2 (aka: KCC2 and SLC12A5) is known to play pivotal roles in the physiology of neurons, and its malfunction has been linked to multiple neurological diseases including seizures, epilepsy, and schizophrenia [29-33]. Indeed, there is a highly conserved binding site of miR-137 on the 3’-UTR sequence of mouse Kcc2 mRNA (position 2229-2235; Fig. 2A). To determine whether miR-137 directly targets Kcc2 mRNA, we cloned the wildtype or mutated 3’-UTR of Kcc2 containing the predicted miR-137 target site into a Renilla luciferase reporter construct, which allowed us to examine KCC2 protein translation by measuring luciferase activities. We found that miR-137 could significantly repress the expression of Renilla luciferase through the 3’-UTR of Kcc2, while miR-137 had no effect on luciferase activity when the conserved binding site was mutated (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

KCC2 is a direct target of miR-137. (A) Sequence alignment of miR-137 and the KCC2 3’-UTR, which contains a predicted conserved miR-137-biding site. The seed-recognizing site in the KCC2 3’-UTR is indicated in red, while the mutant KCC2 3’-UTR site is denoted in green. (B) KCC2 WT 3’-UTR-dependent expression of a Renilla luciferase was reduced, while mutation of the miR-137 binding site in the KCC2 3’-UTR did not affect the Renilla luciferase activity. (C) KCC2 mRNA expression levels were upregulated both in the hippocampus and in the prefrontal cortex of MIR137 cKO mice. (D) KCC2 protein expression levels were upregulated both in the hippocampus and in the prefrontal cortex of MIR137 cKO mice. Left panel, representative images of Western blot. Right panel, quantifications of Western blots with ImageJ. n=3 independent experiments; n.s non-significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

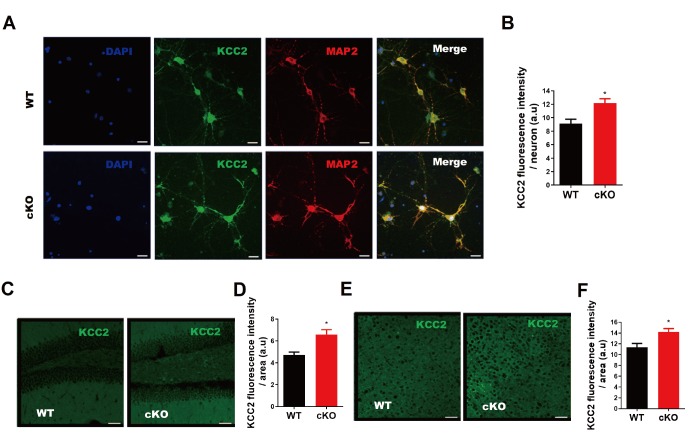

Next, we examined the expression levels of KCC2 in MIR137 cKO and WT brains. Elevated KCC2 mRNA expression levels were observed in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of MIR137 cKO mice compared to their WT littermates (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, our western blot analysis demonstrated that KCC2 protein levels were dramatically increased in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex of MIR137 cKO mice compared to their WT littermates (Fig. 2D). Consistently, immunostaining of cultured hippocampal neurons at DIV 14 with antibodies against KCC2 revealed enhanced KCC2 immunoreactivity in MIR137 cKO neurons (Fig. 3A and 3B). Moreover, KCC2 immunohistochemistry analysis showed a stronger fluorescence intensity in brain sections including hippocampus (Fig. 3C and 3D) and cortex (Fig. 3E and 3F) of MIR137 cKO mice compared to their WT littermates. Taken together, these data support the idea that Kcc2 is a direct downstream target of miR-137 in neurons.

Fig. 3.

KCC2 is upregulated upon the loss of miR-137 both in vitro and in vivo. (A) Representative images of immunostaining of hippocampal neurons at DIV-14) for KCC2 (green) and a mature neuronal marker MAP2 (red). Scale bars, 20 μm. (B) Quantitative analysis showing higher expression of KCC2 in MIR137 cKO hippocampal neurons at DIV-14. (C) Representative images of KCC2 immunostaining of MIR137 WT and cKO hippocampal sections. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Quantitative analysis demonstrating a higher KCC2 immunofluorescence intensity in MIR137 cKO hippocampus. (E) Representative images of KCC2 immunostaining of MIR137 WT and cKO prefrontal cortex sections. Scale bars, 50 μm. (F) Quantification showing an elevated KCC2 immunofluorescence signal in MIR137 cKO prefrontal cortex. n=4 mice per group; *p<0.05.

KCC2 antagonist maintains potassium homeostasis in MIR137 cKO neurons

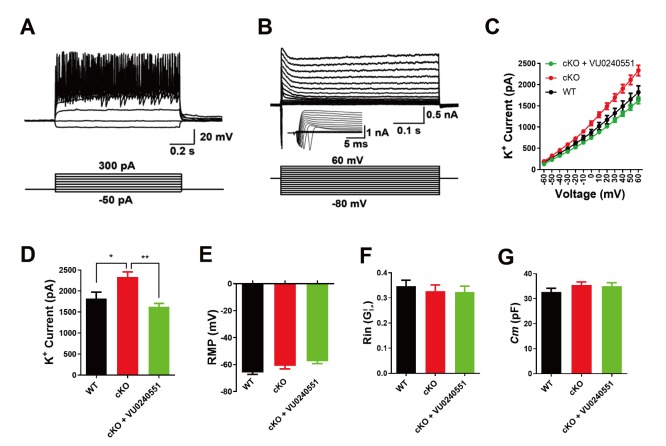

To further explore the role of KCC2 in the electrophysiological properties of neurons, we used a pharmacological agent, the KCC2 antagonist VU0240551, to intervene the function of KCC2 by preincubating neurons with the agent for 1 hour (10 µM), and performed the whole-cell patch-clamp recordings of primary hippocampal neurons at DIV 14. All primary hippocampal neurons elicited multiple action potentials upon the injection of depolarizing currents (Fig. 4A) and large fast-inactivating inward currents followed by outward potassium currents when evoked by a series of voltage steps (Fig. 4B). We then assessed membrane properties of hippocampal neurons that threated with VU0240551 by recording voltage-dependent currents in voltage-clamp mode. We found that maximum peak outward potassium amplitude of VU0240551-treated MIR137 cKO neurons were adjusted to the similar level of WT neurons (Fig. 4C and 4D). VU0240551 did not affect the resting membrane potential (RMP) (Fig. 4E), membrane resistance (Rin) (Fig. 4F), and membrane capacitance (Cm) (Fig. 4G) of hippocampal neurons. Therefore, these data indicate that KCC2 antagonist could maintain potassium homeostasis in MIR137 cKO neurons.

Fig. 4.

KCC2 antagonist maintains potassium homeostasis in mouse MIR137 cKO neurons. (A) Representative traces of action potentials in response to step current injections in primary neurons at DIV-14. Membrane potential was maintained at approximately –65 mV. Step currents were injected from -50 pA to +300 pA in 50 pA increments (bottom panel). WT, n=21; cKO, n=32; cKO+VU0240551, n=26. (B) Representative traces of whole-cell currents in voltage-clamp mode. Primary neurons were held at -70 mV. Step depolarization from -80 mV to +60 mV at 10-mV intervals was delivered (bottom panel). Insets showing respective traces on an expanded scale. WT, n=23; cKO, n=28; cKO+VU0240551, n=33. (C) The relationship between voltage and K+ current. (D) The peak amplitude of K+ current was reduced to normal in MIR137 cKO neurons that were treated with VU0240551, a specific antagonist for KCC2. (E~G) Statistics of intrinsic membrane properties in MIR137 WT and cKO hippocampal neurons treated with or without VU0240551. RMP, resting membrane potential (E); Rin, membrane input resistance (F); Cm, capacitance (G). *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Knockdown of KCC2 ameliorates anxiety-like behavior in MIR137 cKO mice

Recently, we found that mice with forebrain-specific miR-137 loss-of-function can survive to adulthood, but exhibit anxiety-like behavior [19]. To examine whether knockdown of KCC2 might be beneficial to ameliorate anxiety-like behavior in MIR137 cKO mice, we injected lenti-sh-KCC2 virus into the hippocampus and performed behavioral assays at week 3 after grafting.

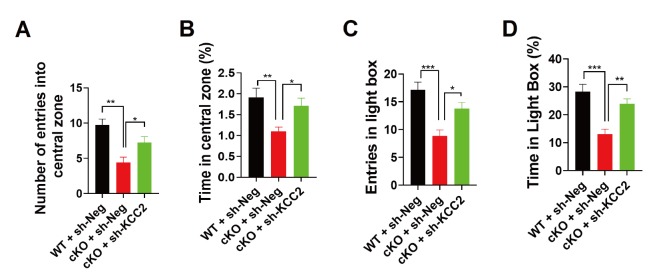

In the open field test, sh-KCC2 significantly ameliorates the anxiety-like behavior in MIR137 cKO mice, as indicated by increased numbers of entries (Fig. 5A) and time spent (Fig. 5B) in the central zone. In consistent with this, the light-dark box test showed that sh-KCC2 did improve entries (Fig. 5C) and time spent (Fig. 5D) in light compartment in MIR137 cKO mice.

Fig. 5.

KCC2 knockdown rescues anxiety-like behaviors in MIR137 cKO mice. (A-B) In the open field test, MIR137 cKO mice with sh-KCC2 treatment dramatically increased the number of entries (A) and time spent (B) in the central zone (n=12~13 mice per group, **p<0.01, *p<0.05). (C, D) In the light/dark box test, sh-KCC2-treated mice demonstrated improved entries (C) and time spent (D) in light box (n=12~13 mice per group, **p<0.01, *p<0.05).

DISCUSSION

Dysfunction of miR-137 has been linked with the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [3], bipolar disorder [4], anxiety and depression [19], and autism spectrum disorders [5, 10]. Fine-tuning the expression of miR-137 is critical in regulating neural development and synaptic plasticity [9, 20, 34]. Overexpression of miR-137 results in changes in synaptic vesicle pool distribution, impaired induction of mossy fiber long-term potentiation and deficits in hippocampus-dependent learning and memory [9]. He et al. [34] then confirmed these observed changes in synaptic transmission upon miR-137 overexpression. Although selective synaptic vesicle docking defects were not obtained, miR-137 overexpression had remarkable effects on docking, active zone length and total vesicle number [34]. Syt1, complexin-1 and neuroligin-3 are known miR-137 targets involved in synapse development [9, 34]. In contrast, a complete knockout of MIR137 in the mouse germline or nervous system leads to postnatal lethality [10, 35], while heterozygous knockout mice display synapse overgrowth, dysregulated synaptic plasticity, repetitive behavior, and anxiety-like behaviors [10, 19]. PDE10a and EZH2 are key experimentally validated targets of miR-137, and knockdown of PDE10a or EZH2 ameliorates the deficits observed in the heterozygous knockout mice [10, 19]. Here we provide the first evidence that miR-137 also plays an important role in the homeostasis of potassium in neurons at least by targeting KCC2, which is a neuron-specific chloride–potassium cotransporter and is highly expressed in the mature CNS [36].

KCC2 mutations or dysfunctions have been identified as a critical component in the development of autism spectrum disorder [37], schizophrenia, epilepsy and seizures [38-42], neuropathic pain [43]. KCC2 has been well-known for its role in maintaining a low intracellular Cl- concentration ([Cl-]i) essential for hyperpolarizing inhibition mediated by GABAA receptors [44], its loss-of-function results in enhanced [Cl-]i which thereby represses the inhibitory strength of GABA and glycine, whose cognate receptors are ligand-gated ion channels permeable to Cl- and HCO3- ions [45-47]. Besides its central role in hyperpolarizing inhibitory signaling based on chloride currents which are mediated by GABA- or glycine-gated receptor channels, KCC2 also acts a structural protein crucially involved in the maturation and regulation of excitatory glutamatergic synapses [48-51]. KCC2 is required for neuronal maturation by rendering GABA hyperpolarizing [49,52-54], and overexpression of KCC2 enhances dendritic spines in the adult nervous system in mice [55]. Therefore, we speculate that the elevated expression of KCC2 may also contribute to dysregulated synaptic plasticity and altered behaviors in MIR137 cKO mice.

Potassium is essential for the proper function of all cells [56]. In neurons, the sodium-potassium flux generates the electrical potential that aids the conduction of nerve impulses [56]. Potassium channels participate in cell ionic balance and serve the fundamental function of supporting action potentials and electrical signal propagation along the neurons and their myelinated axons [57-59]. The increased outward K+ currents in MIR137 cKO mouse neurons were just indirectly measured by mediating voltage gated K+ channels in this study, lacking evidences showing the decreased intracellular Cl- concentration, which presumably also results from the KCC2 up-regulation. Although detailed mechanisms underlying the enhanced K+ currents in MIR137 cKO mouse neurons need further investigations by considering various types of neurons, different developmental stages and brain regions, it is possible that elevated levels of KCC2 in MIR137 cKO neurons simultaneously export more K+ and Cl- ions, while extrusion of Cl- via KCC-mediated K-Cl cotransport is driven by the K+ gradient [60]. A recent study reported that KCC2 interacts with the leak K+ channel Task-3, and promotes its membrane expression, which results in altered neuronal excitability in rat dentate granule cells [61]. The increased outward K+ currents in MIR137 cKO neurons might also reflect a direct modulation of leak K+ channels (e.g. TASK-3) by up-regulated KCC2, not only altered (i.e., decreased) intracellular K+ concentration.

Surprisingly, increased K+ currents in MIR137 cKO mouse neurons in our study did not result in a decrease in action potential firing in these cells as compared to the WT neurons. This could be explained by postulating that primary cultured hippocampal neurons constitute a developmentally and functionally heterogeneous cell population which might not be a good model to examine action potentials. For example, a recent study reported that the KCC2 inhibitor increases the firing rate of P0–P2 rat hippocampal CA3 pyramidal neurons in the absence of glutamatergic transmission, but no change in the output of interneurons synapsing was observed onto pyramidal neurons [62]. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that other unknown targets of miR-137 might play an opposite role in action potentials. For instance, NKCC1 (Slc12a2) is a predicted target of miR-137 by TargetScan algorithm [63]. In mature neurons, NKCC1 and KCC2 respectively mediate inward and outward cotransport of chloride and potassium ions under basal conditions [60]. Whether NKCC1 and other iron transporters also affect the homeostasis of potassium in MIR137 cKO neurons remains to be investigated.

In summary, we show here that miR-137 is a crucial player in the homeostasis of potassium by directly targeting KCC2, and treatment with the KCC2 antagonist can maintain potassium homeostasis in MIR137 knockout hippocampal neurons. Moreover, knockdown of KCC2 ameliorates anxiety-like behavior in MIR137 cKO mice. Considering drugs frequently have ‘hidden phenotypes’ that result from their binding to unknown targets or from unknown interactions between the intended drug target and other biochemical pathways [64], the safety and efficiency of targeting the miR-137-KCC2 pathway in treating neurological disorders should be the focus of future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China Project (2018YFA0108001), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA16010300), the National Science Foundation of China (91753140), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7182107), and the Open Project Program of State Key Laboratory of Stem Cell and Reproductive Biology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barešić A, Nash AJ, Dahoun T, Howes O, Lenhard B. Understanding the genetics of neuropsychiatric disorders: the potential role of genomic regulatory blocks. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:6–18. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0518-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HM, Kim Y. Drug repurposing is a new opportunity for developing drugs against neuropsychiatric disorders. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2016;2016:6378137. doi: 10.1155/2016/6378137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kähler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, Collins AL, Crowley JJ, Fromer M, Kim Y, Lee SH, Magnusson PK, Sanchez N, Stahl EA, Williams S, Wray NR, Xia K, Bettella F, Borglum AD, Bulik-Sullivan BK, Cormican P, Craddock N, de Leeuw C, Durmishi N, Gill M, Golimbet V, Hamshere ML, Holmans P, Hougaard DM, Kendler KS, Lin K, Morris DW, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Neale BM, O'Neill FA, Owen MJ, Milovancevic MP, Posthuma D, Powell J, Richards AL, Riley BP, Ruderfer D, Rujescu D, Sigurdsson E, Silagadze T, Smit AB, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, Suvisaari J, Tosato S, Verhage M, Walters JT, Levinson DF, Gejman PV, Kendler KS, Laurent C, Mowry BJ, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Pulver AE, Riley BP, Schwab SG, Wildenauer DB, Dudbridge F, Holmans P, Shi J, Albus M, Alexander M, Campion D, Cohen D, Dikeos D, Duan J, Eichhammer P, Godard S, Hansen M, Lerer FB, Liang KY, Maier W, Mallet J, Nertney DA, Nestadt G, Norton N, O'Neill FA, Papadimitriou GN, Ribble R, Sanders AR, Silverman JM, Walsh D, Williams NM, Wormley B, Arranz MJ, Bakker S, Bender S, Bramon E, Collier D, Crespo-Facorro B, Hall J, Iyegbe C, Jablensky A, Kahn RS, Kalaydjieva L, Lawrie S, Lewis CM, Lin K, Linszen DH, Mata I, McIntosh A, Murray RM, Ophoff RA, Powell J, Rujescu D, Van Os J, Walshe M, Weisbrod M, Wiersma D, Donnelly P, Barroso I, Blackwell JM, Bramon E, Brown MA, Casas JP, Corvin AP, Deloukas P, Duncanson A, Jankowski J, Markus HS, Mathew CG, Palmer CN, Plomin R, Rautanen A, Sawcer SJ, Trembath RC, Viswanathan AC, Wood NW, Spencer CC, Band G, Bellenguez C, Freeman C, Hellenthal G, Giannoulatou E, Pirinen M, Pearson RD, Strange A, Su Z, Vukcevic D, Donnelly P, Langford C, Hunt SE, Edkins S, Gwilliam R, Blackburn H, Bumpstead SJ, Dronov S, Gillman M, Gray E, Hammond N, Jayakumar A, McCann OT, Liddle J, Potter SC, Ravindrarajah R, Ricketts M, Tashakkori-Ghanbaria A, Waller MJ, Weston P, Widaa S, Whittaker P, Barroso I, Deloukas P, Mathew CG, Blackwell JM, Brown MA, Corvin AP, McCarthy MI, Spencer CC, Bramon E, Corvin AP, O'Donovan MC, Stefansson K, Scolnick E, Purcell S, McCarroll SA, Sklar P, Hultman CM, Sullivan PF Multicenter Genetic Studies of Schizophrenia Consortium; Psychosis Endophenotypes International Consortium; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1150–1159. doi: 10.1038/ng.2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duan J, Shi J, Fiorentino A, Leites C, Chen X, Moy W, Chen J, Alexandrov BS, Usheva A, He D, Freda J, O'Brien NL, McQuillin A, Sanders AR, Gershon ES, DeLisi LE, Bishop AR, Gurling HM, Pato MT, Levinson DF, Kendler KS, Pato CN, Gejman PV Molecular Genetics of Schizophrenia collaboration; Genomic Psychiatric Cohort consortium. A rare functional noncoding variant at the GWAS-implicated MIR137/MIR2682 locus might confer risk to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:744–753. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pinto D, Delaby E, Merico D, Barbosa M, Merikangas A, Klei L, Thiruvahindrapuram B, Xu X, Ziman R, Wang Z, Vorstman JA, Thompson A, Regan R, Pilorge M, Pellecchia G, Pagnamenta AT, Oliveira B, Marshall CR, Magalhaes TR, Lowe JK, Howe JL, Griswold AJ, Gilbert J, Duketis E, Dombroski BA, De Jonge MV, Cuccaro M, Crawford EL, Correia CT, Conroy J, Conceição IC, Chiocchetti AG, Casey JP, Cai G, Cabrol C, Bolshakova N, Bacchelli E, Anney R, Gallinger S, Cotterchio M, Casey G, Zwaigenbaum L, Wittemeyer K, Wing K, Wallace S, van Engeland H, Tryfon A, Thomson S, Soorya L, RogéB, Roberts W, Poustka F, Mouga S, Minshew N, McInnes LA, McGrew SG, Lord C, Leboyer M, Le Couteur AS, Kolevzon A, Jiménez González P, Jacob S, Holt R, Guter S, Green J, Green A, Gillberg C, Fernandez BA, Duque F, Delorme R, Dawson G, Chaste P, CaféC, Brennan S, Bourgeron T, Bolton PF, Bölte S, Bernier R, Baird G, Bailey AJ, Anagnostou E, Almeida J, Wijsman EM, Vieland VJ, Vicente AM, Schellenberg GD, Pericak-Vance M, Paterson AD, Parr JR, Oliveira G, Nurnberger JI, Monaco AP, Maestrini E, Klauck SM, Hakonarson H, Haines JL, Geschwind DH, Freitag CM, Folstein SE, Ennis S, Coon H, Battaglia A, Szatmari P, Sutcliffe JS, Hallmayer J, Gill M, Cook EH, Buxbaum JD, Devlin B, Gallagher L, Betancur C, Scherer SW. Convergence of genes and cellular pathways dysregulated in autism spectrum disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:677–694. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;4:e05005. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szulwach KE, Li X, Smrt RD, Li Y, Luo Y, Lin L, Santistevan NJ, Li W, Zhao X, Jin P. Cross talk between microRNA and epigenetic regulation in adult neurogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:127–141. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200908151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smrt RD, Szulwach KE, Pfeiffer RL, Li X, Guo W, Pathania M, Teng ZQ, Luo Y, Peng J, Bordey A, Jin P, Zhao X. MicroRNA miR-137 regulates neuronal maturation by targeting ubiquitin ligase mind bomb-1. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1060–1070. doi: 10.1002/stem.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegert S, Seo J, Kwon EJ, Rudenko A, Cho S, Wang W, Flood Z, Martorell AJ, Ericsson M, Mungenast AE, Tsai LH. The schizophrenia risk gene product miR-137 alters presynaptic plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1008–1016. doi: 10.1038/nn.4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng Y, Wang ZM, Tan W, Wang X, Li Y, Bai B, Li Y, Zhang SF, Yan HL, Chen ZL, Liu CM, Mi TW, Xia S, Zhou Z, Liu A, Tang GB, Liu C, Dai ZJ, Wang YY, Wang H, Wang X, Kang Y, Lin L, Chen Z, Xie N, Sun Q, Xie W, Peng J, Chen D, Teng ZQ, Jin P. Partial loss of psychiatric risk gene Mir137 in mice causes repetitive behavior and impairs sociability and learning via increased Pde10a. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1689–1703. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0261-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas KT, Anderson BR, Shah N, Zimmer SE, Hawkins D, Valdez AN, Gu Q, Bassell GJ. Inhibition of the schizophrenia-associated microRNA miR-137 disrupts Nrg1¥á neurodevelopmental signal transduction. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright C, Turner JA, Calhoun VD, Perrone-Bizzozero N. Potential impact of miR-137 and its targets in schizophrenia. Front Genet. 2013;4:58. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schulte JT, Wierenga CJ, Bruining H. Chloride transporters and GABA polarity in developmental, neurological and psychiatric conditions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;90:260–271. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon AL, Haan N, Wilkinson LS, Thomas KL, Hall J. CACNA1C: association with psychiatric disorders, behavior, and neurogenesis. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:958–965. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Verkman AS, Smith AJ, Phuan PW, Tradtrantip L, Anderson MO. The aquaporin-4 water channel as a potential drug target in neurological disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2017;21:1161–1170. doi: 10.1080/14728222.2017.1398236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabir ZD, Martínez-Rivera A, Rajadhyaksha AM. From gene to behavior: L-type calcium channel mechanisms underlying neuropsychiatric symptoms. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14:588–613. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0532-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pinggera A, Striessnig J. Cav 1.3 (CACNA1D) L-type Ca2+ channel dysfunction in CNS disorders. J Physiol. 2016;594:5839–5849. doi: 10.1113/JP270672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deisz RA, Wierschke S, Schneider UC, Dehnicke C. Effects of VU0240551, a novel KCC2 antagonist, and DIDS on chloride homeostasis of neocortical neurons from rats and humans. Neuroscience. 2014;277:831–841. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan HL, Sun XW, Wang ZM, Liu PP, Mi TW, Liu C, Wang YY, He XC, Du HZ, Liu CM, Teng ZQ. MiR-137 deficiency causes anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Front Mol Neurosci. 2019;12:260. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, Wang X, Huang W, Ying T, Chen M, Cao J, Wang M. MicroRNA-137 and its downstream target LSD1 inversely regulate anesthetics-induced neurotoxicity in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2017;135:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C, Teng ZQ, Santistevan NJ, Szulwach KE, Guo W, Jin P, Zhao X. Epigenetic regulation of miR-184 by MBD1 governs neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivakine EA, Acton BA, Mahadevan V, Ormond J, Tang M, Pressey JC, Huang MY, Ng D, Delpire E, Salter MW, Woodin MA, McInnes RR. Neto2 is a KCC2 interacting protein required for neuronal Cl- regulation in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212907110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu PP, Tang GB, Xu YJ, Zeng YQ, Zhang SF, Du HZ, Teng ZQ, Liu CM. MiR-203 interplays with polycomb repressive complexes to regulate the proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2017;9:190–202. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu C, Dai SK, Sun Z, Wang Z, Liu PP, Du HZ, Yu S, Liu CM, Teng ZQ. GA-binding protein GABPβ1 is required for the proliferation of neural stem/progenitor cells. Stem Cell Res. 2019;39:101501. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2019.101501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heldt SA, Stanek L, Chhatwal JP, Ressler KJ. Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12:656–670. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahle KT, Khanna AR, Alper SL, Adragna NC, Lauf PK, Sun D, Delpire E. K-Cl cotransporters, cell volume homeostasis, and neurological disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:513–523. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benatar M. Neurological potassium channelopathies. QJM. 2000;93:787–797. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/93.12.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen L, Wan L, Wu Z, Ren W, Huang Y, Qian B, Wang Y. KCC2 downregulation facilitates epileptic seizures. Sci Rep. 2017;7:156. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00196-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Cristo G, Awad PN, Hamidi S, Avoli M. KCC2, epileptiform synchronization, and epileptic disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 2018;162:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2017.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hübner CA. The KCl-cotransporter KCC2 linked to epilepsy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:732–733. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore YE, Deeb TZ, Chadchankar H, Brandon NJ, Moss SJ. Potentiating KCC2 activity is sufficient to limit the onset and severity of seizures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:10166–10171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810134115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore YE, Kelley MR, Brandon NJ, Deeb TZ, Moss SJ. Seizing control of KCC2: a new therapeutic target for epilepsy. Trends Neurosci. 2017;40:555–571. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He E, Lozano MAG, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Sakamoto K, den Oudsten F, Koopmans F, Giamberardino SN, Hammerschlag A, Cornelisse LN, Li KW, van Weering J, Posthuma D, Smit AB, Sullivan PF, Verhage M. MIR137 schizophrenia-associated locus controls synaptic function by regulating synaptogenesis, synapse maturation and synaptic transmission. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:1879–1891. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddy089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crowley JJ, Collins AL, Lee RJ, Nonneman RJ, Farrell MS, Ancalade N, Mugford JW, Agster KL, Nikolova VD, Moy SS, Sullivan PF. Disruption of the microRNA 137 primary transcript results in early embryonic lethality in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:e5–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tillman L, Zhang J. Crossing the chloride channel: the current and potential therapeutic value of the neuronal K+-Cl- cotransporter KCC2. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:8941046. doi: 10.1155/2019/8941046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merner ND, Chandler MR, Bourassa C, Liang B, Khanna AR, Dion P, Rouleau GA, Kahle KT. Regulatory domain or CpG site variation in SLC12A5, encoding the chloride transporter KCC2, in human autism and schizophrenia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:386. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puskarjov M, Seja P, Heron SE, Williams TC, Ahmad F, Iona X, Oliver KL, Grinton BE, Vutskits L, Scheffer IE, Petrou S, Blaesse P, Dibbens LM, Berkovic SF, Kaila K. A variant of KCC2 from patients with febrile seizures impairs neuronal Cl- extrusion and dendritic spine formation. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:723–729. doi: 10.1002/embr.201438749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kahle KT, Merner ND, Friedel P, Silayeva L, Liang B, Khanna A, Shang Y, Lachance-Touchette P, Bourassa C, Levert A, Dion PA, Walcott B, Spiegelman D, Dionne-Laporte A, Hodgkinson A, Awadalla P, Nikbakht H, Majewski J, Cossette P, Deeb TZ, Moss SJ, Medina I, Rouleau GA. Genetically encoded impairment of neuronal KCC2 cotransporter function in human idiopathic generalized epilepsy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:766–774. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stödberg T, McTague A, Ruiz AJ, Hirata H, Zhen J, Long P, Farabella I, Meyer E, Kawahara A, Vassallo G, Stivaros SM, Bjursell MK, Stranneheim H, Tigerschiöld S, Persson B, Bangash I, Das K, Hughes D, Lesko N, Lundeberg J, Scott RC, Poduri A, Scheffer IE, Smith H, Gissen P, Schorge S, Reith ME, Topf M, Kullmann DM, Harvey RJ, Wedell A, Kurian MA. Mutations in SLC12A5 in epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8038. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saitsu H, Watanabe M, Akita T, Ohba C, Sugai K, Ong WP, Shiraishi H, Yuasa S, Matsumoto H, Beng KT, Saitoh S, Miyatake S, Nakashima M, Miyake N, Kato M, Fukuda A, Matsumoto N. Impaired neuronal KCC2 function by biallelic SLC12A5 mutations in migrating focal seizures and severe developmental delay. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30072. doi: 10.1038/srep30072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Magloire V, Cornford J, Lieb A, Kullmann DM, Pavlov I. KCC2 overexpression prevents the paradoxical seizure-promoting action of somatic inhibition. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1225. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08933-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coull JA, Boudreau D, Bachand K, Prescott SA, Nault F, Sík A, De Koninck P, De Koninck Y. Trans-synaptic shift in anion gradient in spinal lamina I neurons as a mechanism of neuropathic pain. Nature. 2003;424:938–942. doi: 10.1038/nature01868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HH, Deeb TZ, Walker JA, Davies PA, Moss SJ. NMDA receptor activity downregulates KCC2 resulting in depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nn.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medina I, Friedel P, Rivera C, Kahle KT, Kourdougli N, Uvarov P, Pellegrino C. Current view on the functional regulation of the neuronal K(+)-Cl(-) cotransporter KCC2. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:27. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hübner CA, Stein V, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Meyer T, Ballanyi K, Jentsch TJ. Disruption of KCC2 reveals an essential role of K-Cl cotransport already in early synaptic inhibition. Neuron. 2001;30:515–524. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu L, Lovinger D, Delpire E. Cortical neurons lacking KCC2 expression show impaired regulation of intracellular chloride. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1557–1568. doi: 10.1152/jn.00616.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blaesse P, Schmidt T. K-Cl cotransporter KCC2--a moonlighting protein in excitatory and inhibitory synapse development and function. Pflugers Arch. 2015;467:615–624. doi: 10.1007/s00424-014-1547-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K+/Cl- co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Khirug S, Cai C, Ludwig A, Blaesse P, Kolikova J, Afzalov R, Coleman SK, Lauri S, Airaksinen MS, Keinänen K, Khiroug L, Saarma M, Kaila K, Rivera C. KCC2 interacts with the dendritic cytoskeleton to promote spine development. Neuron. 2007;56:1019–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gauvain G, Chamma I, Chevy Q, Cabezas C, Irinopoulou T, Bodrug N, Carnaud M, Lévi S, Poncer JC. The neuronal K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 influences postsynaptic AMPA receptor content and lateral diffusion in dendritic spines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15474–15479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107893108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vanhatalo S, Palva JM, Andersson S, Rivera C, Voipio J, Kaila K. Slow endogenous activity transients and developmental expression of K+-Cl- cotransporter 2 in the immature human cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:2799–2804. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abbah J, Juliano SL. Altered migratory behavior of interneurons in a model of cortical dysplasia: the influence of elevated GABAA activity. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24:2297–2308. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gagnon KB, Di Fulvio M. A molecular analysis of the Na(+)-independent cation chloride cotransporters. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2013;32:14–31. doi: 10.1159/000356621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nakamura K, Moorhouse AJ, Cheung DL, Eto K, Takeda I, Rozenbroek PW, Nabekura J. Overexpression of neuronal K+-Cl- co-transporter enhances dendritic spine plasticity and motor learning. J Physiol Sci. 2019;69:453–463. doi: 10.1007/s12576-018-00654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pohl HR, Wheeler JS, Murray HE. Sodium and potassium in health and disease. Met Ions Life Sci. 2013;13:29–47. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7500-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duménieu M, OuléM, Kreutz MR, Lopez-Rojas J. The segregated expression of voltage-gated potassium and sodium channels in neuronal membranes: functional implications and regulatory mechanisms. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:115. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huffaker SJ, Chen J, Nicodemus KK, Sambataro F, Yang F, Mattay V, Lipska BK, Hyde TM, Song J, Rujescu D, Giegling I, Mayilyan K, Proust MJ, Soghoyan A, Caforio G, Callicott JH, Bertolino A, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Chang J, Ji Y, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Kleinman JE, Lu B, Weinberger DR. A primate-specific, brain isoform of KCNH2 affects cortical physiology, cognition, neuronal repolarization and risk of schizophrenia. Nat Med. 2009;15:509–518. doi: 10.1038/nm.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Heide J, Mann SA, Vandenberg JI. The schizophrenia-associated Kv11.1-3.1 isoform results in reduced current accumulation during repetitive brief depolarizations. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blaesse P, Airaksinen MS, Rivera C, Kaila K. Cation-chloride cotransporters and neuronal function. Neuron. 2009;61:820–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goutierre M, Al Awabdh S, Donneger F, François E, Gomez-Dominguez D, Irinopoulou T, Menendez de la Prida L, Poncer JC. KCC2 regulates neuronal excitability and hippocampal activity via interaction with task-3 channels. Cell Rep. 2019;28:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spoljaric I, Spoljaric A, Mavrovic M, Seja P, Puskarjov M, Kaila K. KCC2-mediated Cl- extrusion modulates spontaneous hippocampal network events in perinatal rats and mice. Cell Rep. 2019;26:1073–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MacDonald ML, Lamerdin J, Owens S, Keon BH, Bilter GK, Shang Z, Huang Z, Yu H, Dias J, Minami T, Michnick SW, Westwick JK. Identifying off-target effects and hidden phenotypes of drugs in human cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:329–337. doi: 10.1038/nchembio790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]