Abstract

Despite developments to improve health in the United States, racial and ethnic disparities persist. These disparities have profound impact on the wellbeing of historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups. This narrative review explores disparities by race in people living with cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). We discuss selected common social determinants of health for both of these conditions which include; regional historical policies, incarceration, and neighborhood effects. Data on racial disparities for persons living with comorbid HIV and CVD are lacking. We found few published articles (n=7) describing racial disparities for persons living with both comorbid HIV and CVD. Efforts to reduce CVD morbidity in historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV must address participation in clinical research, social determinants of health and translation of research into clinical practice.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, HIV, racial disparities, historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups, people living with HIV

Health disparities are differences in the indicators of health of different population groups often defined by race, ethnicity, sex, educational level, socioeconomic status, and geographic location of residence.(1) Discrimination of historically marginalized groups can influence an individual’s ability to achieve optimal health.(2,3) Despite advances in medical care and infrastructure to improve health in the United States (US), racial and ethnic disparities continue to contribute to persistent inequities.(1) Health disparities take on many forms for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups in the US, including higher rates of infections, chronic diseases, and premature death. For example, marginalized racial and ethnic groups have a disproportionately higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and infection with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the causative agent of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in the US.(4,5) This narrative review explores published literature on racial disparities in CVD and HIV in the US, selected common determinants of health status for each condition, and offers recommendations to fill knowledge gaps in this area with an aim towards ultimately improving health for people living with HIV and CVD who belong to historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups.

Disparities in CVD and Risk Factors

CVD is the leading cause of death in the US.(6,7) Although CVD mortality rates have declined in recent years due to advances in care, rates for African -Americans have largely remained stable.(8) Sixty percent of African-American men and 57% of African-American women have some form of CVD.(7) Among the different historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups, African-American females have the highest overall death rate from CVD, with 32.8% attributable mortality from this condition.(7) African-American and American Indian/Alaskan Native females have among the top three highest stroke-related death rates among US women.(7) In the US, CVD and stroke disproportionately affects adults from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups at an earlier age than whites.(9,10) In terms of CVD risk factors, African-Americans have among the highest hypertension (HTN) rates in the world and are among the least likely to achieve blood pressure (BP) control.(11) Table 1 highlights selected disparities between different historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups; an indicator that tailoring CVD prevention interventions to fit specific marginalized racial and ethnic groups is critical. It is worth noting that there is limited data from national and state-based surveillance systems on American Indian/Alaska natives, which may misrepresent the true burden of CVD and risk factors in this particular population.

Table 1.

Selected Disparities for CVD risk and risk factors for different historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups.

| Race | African American | Non-White Hispanic | Asian American/Pacific Islander |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total CVD risk | More likely to die from acute coronary syndrome. Higher rate of stroke, myocardial infarction and heart failure compared to Whites | Lower rate of heart failure compared to AA but higher than for non-Hispanic whites. | Higher prevalence of coronary artery disease earlier in life among Asian Indians compared to other race/ethnic groups |

| Traditional and non-traditional CVD risk factors |

Hypertension: Higher likelihood of having high blood pressure. Lower likelihood to achieve blood pressure under control compared to Whites Obesity: Higher rate of obesity compared to other race/ethnic groups |

Metabolic syndrome: Mexican Americans have the highest rate of prevalence of metabolic syndrome compared to other race/ethnic groups. |

Lipids: Lipoprotein levels are higher in Indians than any other race/ethnic groups. Nontraditional CVD risk: South Asians have increased inflammatory markers and rates of insulin resistance. Smoking: Korean Americans, Vietnamese Americans and Filipino American males have some of the highest smoking rates compared to other race/ethnic groups |

Source: Adapted from Graham G. Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015. (11)

Disparities in HIV

It is estimated that there are over 1 million people were living with diagnosed HIV-infection in the US in 2017.(5) While African-Americans make up only 13% of the overall US population, this group accounts for 41% of people living with HIV and 41% of new HIV diagnoses.(5) From 2013–2017, the rate of new diagnoses increased for American Indians/Alaska Natives and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, remained stable for Asians and Hispanics, and decreased for African-Americans and Whites. Over the same time period, the rate of death due to HIV among Asians increased, while death rates decreased for other historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups and whites.

Social Determinants of Health

Common roots of health disparities faced by historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV and CVD can be evaluated through the social determinants of health framework.(12) Social determinants of health are conditions in the environments in which people live, learn, work, play, and worship that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality of life outcomes and risks.(12) The neighborhood where one lives can affect health through the social environment e.g. high crime rate, pollution or availability of institutions and resources such as healthy food, places to exercise or play, and health care.(13) In this section we will explore selected shared origins of racial disparities and the relationship between the individual and the underlying social structures that yield similar health trajectories for CVD and HIV.

While CVD and HIV have very different disease courses, the patterns of disparities for both diseases lead to high morbidity, disability, and mortality.(14) At a biological level, it has been demonstrated that HIV-infection is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and heart failure. Although HIV-specific factors have a role, traditional risk factors account for the vast majority of population level risk.(15–19)

Neighborhood Effects

The neighborhood where one lives has a direct impact on health and related CVD and HIV disparities in several ways. Disproportionate investments in parks and green space, which provide more opportunities to exercise safely, have been positively associated with elevated CVD risk.(20) Using HIV surveillance data, Xia et al. found that compared with African-Americans living in the most impoverished neighborhoods, Whites in the most impoverished neighborhoods and Blacks in the least impoverished neighborhoods were 11% and 7% more likely to be HIV virally suppressed.(21)

Regional Historical Policies

The U.S history of legalized slavery, sharecropping and Jim Crow segregation has led to persistent racial inequality and discrimination.(22) Furthermore, medical mistrust among Black populations due to the legacies of the Tuskegee and other experiments remains high in some settings, which can contribute to lower health seeking behaviors for HIV and CVD.(23,24) This social inequity can exacerbate disparities in social determinants of health and subsequent health outcomes.

In the U.S., it is estimated that 55% of African-Americans reside in the South, much higher than any other U.S. region.(25) At the policy level, federal funding for HIV care and prevention per person living with HIV has historically been lowest in the South compared to the US overall.(26) Few southern states elected to expand Medicaid, which has led to an increased reliance on limited federal Ryan White funding for HIV care services.(27) It has been shown that Medicaid expansion has been associated with a significant increase in HIV testing rates among individuals below 138% of the federal poverty level.(28) It is likely that these trends would translate to other important HIV care continuum of outcomes (i.e., diagnosis, treatment initiation and viral suppression). Khatana and colleagues found that counties in states that had Medicaid expansion were associated with lower CVD mortality in middle-aged adults.(29)

Incarceration

Incarceration has been shown to negatively impact both HIV and CVD outcomes, and approximately 40% of those incarcerated in the US are African-American.(30) This disproportionate incarceration of African-Americans has been shown to negatively influence sexual networks in African-American communities, leading to higher rates of concurrent sexual relationships, a risk factor for HIV transmission. Moreover, people tend to choose sexual partners of the same race which leads to further HIV transmission risk within the African-American community.(31) In the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study, Wang et al. found that history of incarceration was associated with higher incidence of hypertension and higher likelihood of left ventricular hypertrophy. Howell et al. also found that history of incarceration was associated with higher risk of uncontrolled HTN.(32,33)

Unemployment.

In 2018, the overall unemployment rate in the U.S. was 3.9%. Unemployment rates were higher for American Indians/Alaska Natives (6.6%), African-American (6.5%), Native Hawaiians/Other Pacific Islanders (5.4%), and Hispanics (4.7%) compared to the US overall.(34) Unemployment may lead to many downstream effects like loss of insurance coverage and also food insecurity. Those dealing with food insecurity have lower likelihood of achieving HIV viral suppression and may be more likely to engage in sexual relationships in exchange for food or money. (35) Dupre et al. found that unemployment status, multiple job losses and short periods without work were all significant risk factors for acute CVD events.(36) Disruption in employment may affect the ability to secure high-quality food which in turn has a direct effect on CVD outcomes.

Poverty

In 2014, it was estimated that almost 15% of the U.S. population was living in poverty, although there were striking differences by race/ethnicity; 28.3% of Native Americans, 26.2% of African-Americans, 23.6% of Hispanics, 12% of Asians, and 10% of Whites were estimated to be living in poverty.(37) High poverty rates have been shown to correlate with a higher burden of many diseases, including HIV.(38) Poverty, in turn, can contribute to suboptimal education, unstable housing, food insecurity, poor transportation access, and significant trauma/violence experiences, all of which impact HIV and CVD health outcomes.(39–42) Poverty also leads to homelessness and housing instability which is a barrier for treatment adherence for people with HIV.(43) Table 2 summarizes selected common social determinants of health disparities for HIV and CVD.

Table 2.

Selected common roots of health disparities in HIV and CVD

| Social determinant of health Domains(12) | Common roots of health disparities in HIV and CVD |

|---|---|

| Neighborhood and build environment | |

| Social and Community context | |

| Physical Environment |

Disparities Within Disparities for Historically Marginalized Racial and Ethnic Groups with CVD and HIV

When individuals from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups living with HIV have CVD, they experience an additive, if not synergistic impact on health disparities. This raises another dimension of “disparities within disparities” faced by historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups between and within the individual diseases. For example, African-Americans living with HIV have been found to have more poorly controlled BP/HTN, DM and lipid management compared to Whites living with HIV.(44,45) Some have also found increased CVD risk in Hispanics living with HIV compared to Whites living with HIV.(46) In the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials cohort, stroke incidence in non-Hispanic Blacks living with HIV was found to be higher than Whites living with HIV.(47,48) Blacks and Hispanics living with HIV have among the highest estimated 10-year risk of CVD compared with other racial and ethnic groups.(46,49)

Inattention to Racial Disparities in CVD among Historically Marginalized Racial and Ethnic Groups with HIV

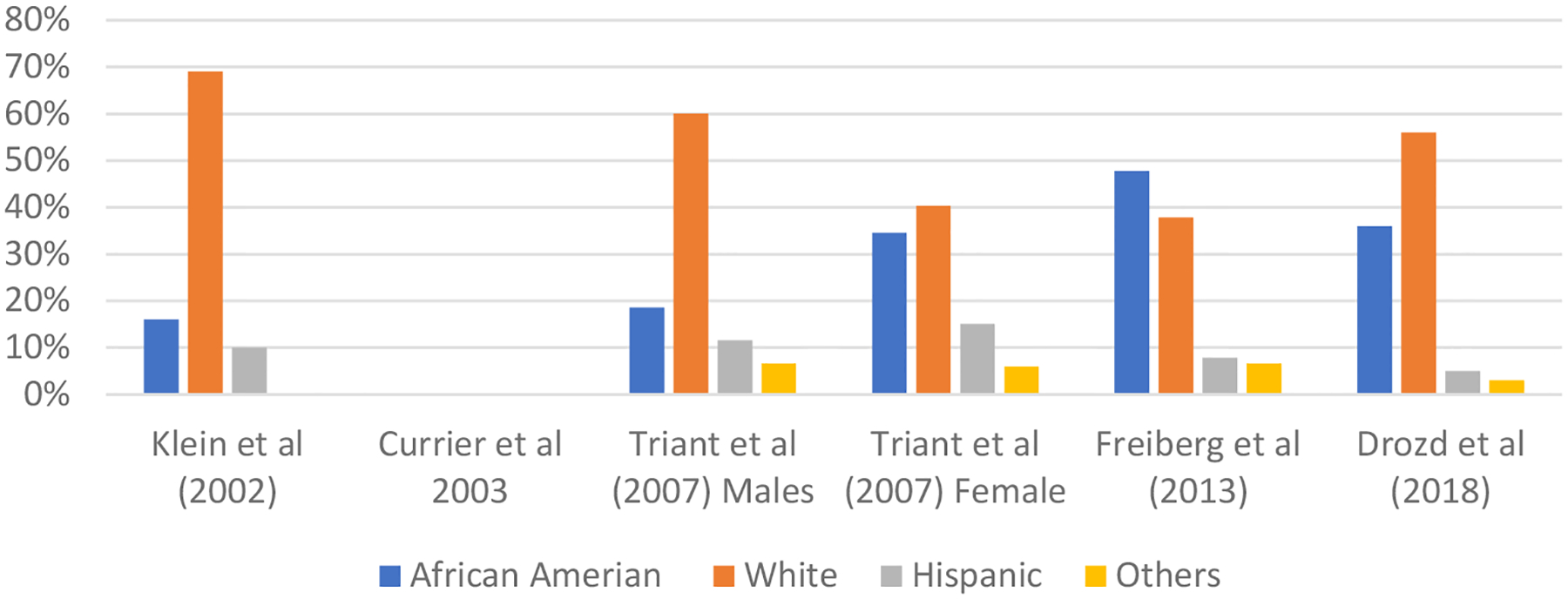

Those from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups living with HIV and CVD endure particular health disparities and therefore it is imperative for the research community to focus on reducing this disparities gap. In order to describe the representativeness of historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups in studies from large HIV cohorts, we examined the race distribution of some of the largest studies that evaluated the association of HIV with risk for myocardial infarction that included an HIV-uninfected comparator group.(15,50–53) Figure 1 below shows that but for the exception of 1 study, (15) multiple studies included fewer African-American compared to whites and one did not report on the racial composition of their cohort.(52) In order to close the disparities gap, increased representativeness of historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups in studies is critical.

Figure 1.

Race distribution in Selected Studies Reporting Myocardial Infarction Rates in People Living with HIV and Uninfected Controls

Beyond representativeness in research, we also examined the current landscape of published research on racial disparities in CVD for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups living with HIV. We conducted a narrative literature review with a particular interest in published articles whose primary focus or outcome was CVD racial disparities for people living with HIV. We searched PubMed including MEDLINE to identify articles published in English through September 1, 2019 using a combination of key words and phrases: “Cardiovascular Diseases/epidemiology and HIV”, “AIDS”, “racial disparities”, “Race differences”, “Minority Groups”, “Minority Health”, “African American*”, “Black”, “Hispanic Americans*”, “Latino” “Latina “Oceanic Ancestry Group”, “Indians, North American”, “Native American”, “American Indian”, and “Asian American*” in combinations to capture disease states and historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups.

We determined eligibility by title and abstract review to determine if the main objective of the study was to assess racial disparities or differences in CVD among people living with HIV. Eligible articles were then abstracted for a full review. We deemed articles to be focused on racial disparities as their primary focus if they had extensive discussion on future direction or interventions needed to close the disparities gap.

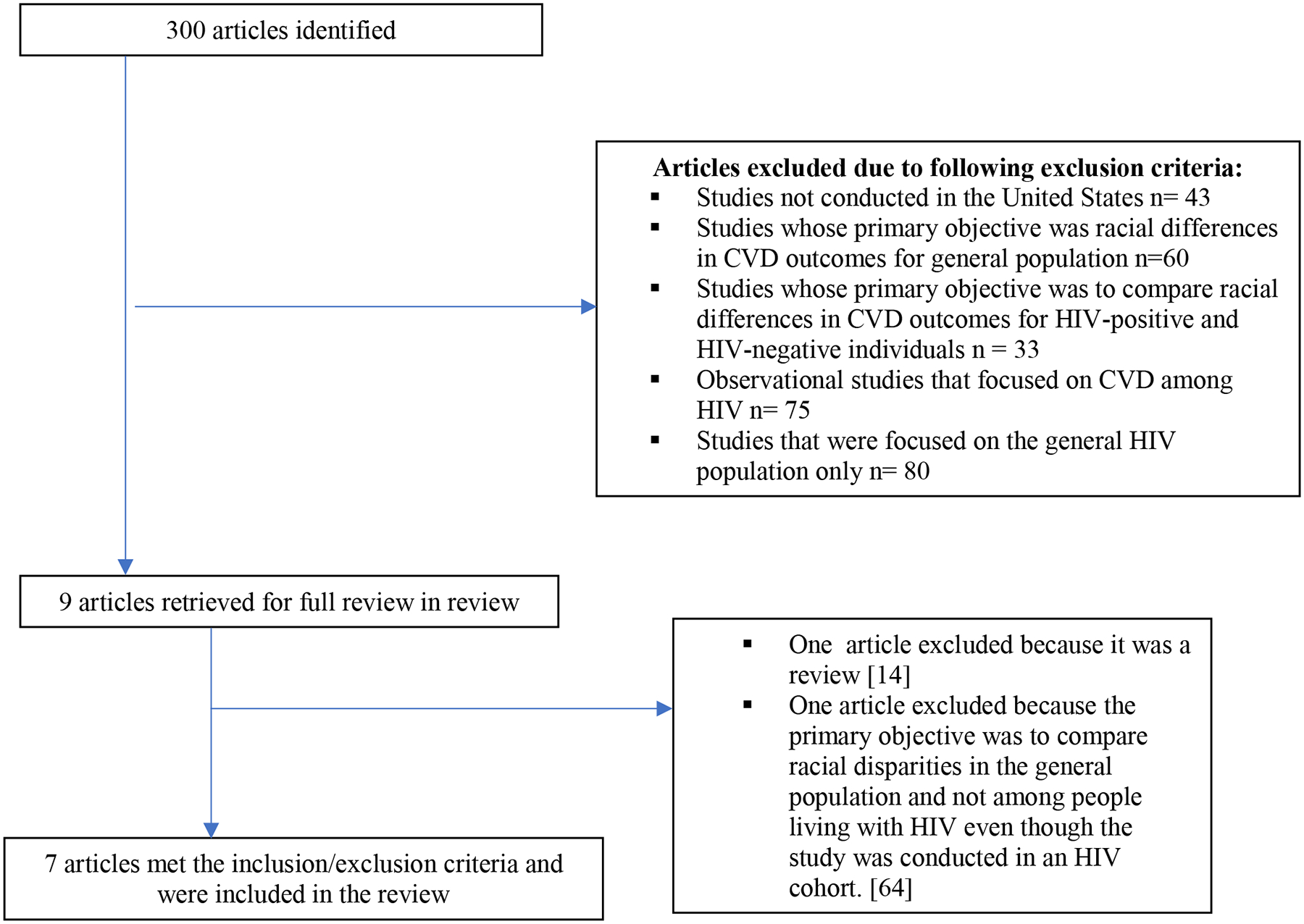

Our search yielded 300 articles, of which 291 were excluded for reasons specified in Figure 2. Most exclusions were due to not having racial disparities as a primary outcome. Only 7 studies met the criteria of study having CVD disparities in marginalized racial and ethnic groups living with HIV as a primary focus or outcome.(44,45,54–58)

Figure 2.

Studies identified by literature search and reasons for exclusion to arrive at 7 studies that were included in the review

Of the eligible studies, five were retrospective cohort studies and two were cross-sectional. Studies were published between 2014 and 2019 and all but one compared outcome between African-Americans and Whites living with HIV. African-Americans were found to have poor CVD outcomes compared to whites.(Table 3) For example, Burkholder et al. found that despite comparable levels of HTN treatment, African-Americans were less likely to achieve BP control.(56) Richardson et al. found that Black veterans living with HIV were less likely than their White counterparts to achieve HTN, DM and lipid control. (45) Willig et al. also found that compared to Whites, African-American men had increased odds for HTN and chronic kidney disease (CKD), while Black women had a nearly 2-fold increased odds for DM and HTN.(54) Using data from North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), Wong et al. examined whether disparities existed in the first occurrence of HTN, DM and CKD between different demographic groups. In this study, African-American adults experienced at least a 1.4-fold higher rate of HTN, DM and CKD compared to non-African-American individuals.(59) Kent et al. found that nighttime systolic and diastolic BP was higher among African-American compared to Whites living with HIV.(44) Using the US national hospital discharge surveys database, Oramasionwu and colleagues found that African-Americans living with HIV had increased odds of CVD-related hospitalization compared to whites with HIV.(60) Finally, Riestenberg et al. found that among people with HIV who had an indication for a statin, African-Americans and Hispanics were less likely than Whites to have been prescribed statins.(57) Because of epistemological constraints of narrative literature review,(61) we offer reflections on the implications and future direction in order to reduce the racial disparities gap.

Table 3:

Published articles on racial disparities in CVD for historically marginalize racial and ethnic groups with HIV

| Author | Year | Race | Data Sources/Setting | Study Design | Sample Size | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kent et al. (44) | 2017 | Whites & African-Americans | HIV Clinic | Cross-sectional | 49 | SBP and DBP dipping ratios were 5.2% (95%CI: 1.7%, 8.7%) and 6.1% (95%CI 2.0%, 10.3%) smaller among African-Americans compared with Whites. |

| Burkholder et al. (56) | 2018 | Whites & African-Americans | HIV Clinic | Cross-sectional | 1,664 | Prevalence of HTN was higher among African-Americans compared to Whites (PR 1.25; 95% CI 1.12–1.39) and prevalence of BP control was lower (PR 0.80; 95% CI 0.69–0.93). |

| Richardson et al. (45) | 2016 | Whites & African-Americans | Veterans Health Administration (VHA) | Retrospective Cohort | 23,974 | Black veterans living with HIV were less likely than their White counterparts to receive antiretroviral therapy and experience viral control (84.6% vs. 91.3%, p<.001), HTN control (61.9% vs. 68.3%, p<.001), DM control (85.5% vs. 89.5%, p<.001), and lipid monitoring (81.5% vs. 85.2%, p<.001) |

| Wong et al. (55) | 2017 | African-Americans & non-African- Americans | North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD) | Retrospective Cohort | 50,000 | African-American adults experienced at least a 1.4-fold higher rate of HTN, DM and CKD compared to non-African-American individuals |

| Oramasionwu et al.(60) | 2014 | Whites & African-Americans | United States National Hospital Discharge Surveys (NHDS) | Retrospective Cohort | 1.5 million hospital discharges | African-Americans living with HIV had increased odds of CVD-related hospitalization compared to whites with HIV (OR, 1.45 95% CI, 1.39 –1.51) |

| Riestenberg et al. (57) | 2019 | Whites & African-Americans | HIV Electronic Comprehensive Cohort of CVD Complications (HIVE-4CVD) | Retrospective Cohort | 5,039 | Among people with HIV who had an indication for a statin, African-Americans and Hispanics were less likely than Whites to have been prescribed statins. |

| Willig et al. (54) | 2015 | Whites & African-Americans | HIV Clinic | Retrospective Cohort | 1800 | Compared to Whites, African-American men had increased odds for HTN and CKD, while African-American women had a nearly 2-fold increased odds for DM and HTN (p<0.01). |

Implications for Future Research

As efforts to reduce CVD morbidity in people living with HIV expand, we must intentionally include strategies for vulnerable groups such as historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups. A comprehensive research agenda to mitigate differences in CVD outcomes among historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV is likely to fill major gaps in knowledge and ultimately help achieve health equity. As in other research domains, racial and ethnic differences exist in recruitment, retention, and trust in clinical research for people with HIV. Yet, participation of historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV in clinical research is a critical link between scientific innovation and improvements in healthcare delivery and CVD outcomes. Approaches to achieve racial and ethnic equity in improvements in the CVD burden/outcomes for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV must address participation in clinical research, social determinants of health and translation of research to clinical practice for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV.

Participation in Clinical Research

In response to disparities in participation in clinical research, the National Institutes of Health passed the 1993 Revitalization Act which was intended, among other aims, to diversify research populations. Yet, the promise of the act has not been fulfilled as non-white racial groups remain grossly underrepresented in cardiovascular research.(62) The most commonly cited barriers to participating in clinical research among historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups are knowledge, awareness, confusing terminology, trust and transportation, while facilitators include altruism, hearing from a trusted source and access to transportation.(63) Particular attention needs to be paid to historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV to overcome the common barriers. For those with HIV, the critical role of the primary HIV provider cannot be overstated in terms of increasing knowledge and awareness of research opportunities. Owing to historical stigma and HIV disease treatment over the last few decades, the advice and affirmation from a known HIV provider is likely to greatly increase the likelihood that patients would enroll in clinical studies. To enhance participation in research especially for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups , the active engagement of Community Advisory Boards (CABs) will be critical.(64) CABs function as liaisons between researchers and the community and their use has been associated with a sense of mutual trust and collective ownership when used in studies.(65)

For historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV, many of whom may reside in rural settings, strategies to budget and arrange transportation for study visits may also enhance participation rates. Moreover, remote study visits via phone, telehealth or other means could address the transportation barrier. Future cardiovascular research in people with HIV should also address patients for whom English is a second language, as this segment of the U.S. population continues to expand.(66)

A lack of racial and ethnic diversity in research teams continues to be problematic. Scientists from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups are more likely to conduct research in minority populations and may more easily gain the trust of participants who look like them.(67) Researchers from historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups are more likely to study topics related to racial/ethnic disparities, despite the fact that topic choice in research accounts for a significant funding gap for African-American scientists.(68) These scientists may therefore be in a unique position to advance this field and should be supported.

Social Determinants of Health

People living with HIV face unique barriers to optimal cardiovascular health as a result of numerous social determinants of health spanning the socio-political context, socioeconomic position, material circumstances and social capital. The burden of these factors - when they present as barriers - has been described in the setting of clinical studies for a variety of racial and ethnic groups living with HIV.(45,46,69) These barriers have also been well articulated by HIV treatment advocates from the perspective of a patient’s lived experience.(4,70) Determinants of health such as education level, healthcare literacy, injection drug use, socioeconomic status, neighborhood environment, racism, privilege and other factors serve as a double-blow to historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV – being more commonly found in this group and portends heightened risks for CVD regardless of HIV status.(71,72) Future research in this area should consider these social determinants as factors that impact cardiovascular health as interventions.

Translation to Clinical Practice

Methods to promote adoption and implementation of known effective therapies for CVD must be deployed specifically for historically disenfranchised racial and ethnic groups. The inequities in treatment and testing for CVD in the historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV have been well-described.(45) Owing to the multi-level nature of the disparities in CVD care, programs to improve CVD care should be transdisciplinary, addressing both the biomedical and social determinants of health. System-level interventions (i.e., deploying staff in novel ways, enhancing the referral process, contemporary communication technology) should be considered alongside application of guideline-directed medical therapy such as the nurse-led intervention to extend the HIV treatment cascade for CVD prevention (EXTRA-CVD) trial and other studies from the National Heart Lung & Blood Institute PRECLUDE consortium.(73)

While guidelines for CVD screening and treatment in people living with HIV are nascent and largely driven by expert opinion, we must ask the following question: How can we deliver better evidence-based therapies for vulnerable historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups with HIV? Implementation science methodology is well-poised to address this question. Many aspects of implementing evidence-based therapies for people with HIV are likely to be impacted by enhancing patient participation in these efforts. Frameworks for participants engagement from the social sciences and the International Association of Public Participation highlight approaches such as community-based participatory research, delineation of roles, information and communication technology and institutionalizing patient engagement as factors likely to achieve the widespread implementation and sustainability.(74,75) As for the evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions, process measures (e.g., fidelity to an intervention, dose delivered, dose received, reach, etc.) should be included a priori to ensure that the intended benefit is realized equitably for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups (76)

Conclusion

In this narrative review we evaluated common origins of racial disparities for CVD and HIV. We further demonstrated how social determinants of health can, in part, explain these observed disparities. Racial and ethnic disparities place individuals at a higher risk for both acquiring HIV and developing CVD. Finally, we provided a review of literature addressing disparities for persons living with both conditions and offered recommendations to reduce disparities for historically marginalized racial and ethnic groups living with HIV and CVD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding: This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Grant U01HL142099 and National Institute of Minority Health and Development Grant # R01 MD013493. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Alphabetical List of Abbreviations:

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- US

United States

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- BP

Blood pressure

- HTN

Hypertension

- CABs

Community Advisory Boards

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest:

Dr. Longenecker reports research grants Gilead Sciences and served on an advisory board for Esperion Therapeutics. Dr. Meissner reports research support from Viiv Healthcare. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts or competing interests.

References:

- 1.National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Community-Based Solutions to Promote Health Equity in the United States The State of Health Disparities in the United States. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease. Allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1998;840:33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation 2005;111:1233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feinstein MJ, Hsue PY, Benjamin LA et al. Characteristics, Prevention, and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;140:e98–e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC:. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2018 (Preliminary). HIV Surveillance Report, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heron M. National Vital Statistics Reports;. 68(6) ed, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carnethon MR, Pu J, Howard G et al. Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017;136:e393–e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;133:e38–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2014;130:593–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham G Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk in the United States. Curr Cardiol Rev 2015;11:238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.2020 HP. Social Determinants of Health; USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics 2006;117:417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang ME, Bird CE. Understanding and Addressing the Common Roots of Racial Health Disparities: The Case of Cardiovascular Disease and HIV/AIDS in African Americans. Health Matrix Clevel 2015;25:109–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:614–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Butt AA, Chang CC, Kuller L et al. Risk of heart failure with human immunodeficiency virus in the absence of prior diagnosis of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:737–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Currier JS, Lundgren JD, Carr A et al. Epidemiological evidence for cardiovascular disease in HIV-infected patients and relationship to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Circulation 2008;118:e29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Triant VA. HIV infection and coronary heart disease: an intersection of epidemics. J Infect Dis 2012;205 Suppl 3:S355–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril JG, Lelorier J, Tremblay CL. Association between HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy, and risk of acute myocardial infarction: a cohort and nested case-control study using Quebec’s public health insurance database. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2011;57:245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Muntaner C et al. Neighborhood environments and coronary heart disease: a multilevel analysis. Am J Epidemiol 1997;146:48–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xia Q, Robbins RS, Lazar R, Torian LV, Braunstein SL. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in viral suppression among persons living with HIV in New York City. Ann Epidemiol 2017;27:335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter JS. A Cosmopolitan Way of Life for All?:A Reassessment of the Impact of Urban and Region on Racial Attitudes From 1972 to 2006. Journal of Black Studies 2010;40:1075–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bogart LM, Ransome Y, Allen W, Higgins-Biddle M, Ojikutu BO. HIV-Related Medical Mistrust, HIV Testing, and HIV Risk in the National Survey on HIV in the Black Community. Behav Med 2019;45:134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carnethon MRPJ, Howard G, Albert MA, Anderson CAM, Bertoni AG, Mujahid MS, Palaniappan L, Taylor HA Jr, Willis M, Yancy CW; on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Lifelong Congenital Heart Disease and Heart Health in the Young; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology; and Stroke Council. Eliminating Cardiovascular Health Disparities in African Americans: Are We Any Closer to Closing the Gap? Circulation, American Heart Association; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bureau UC. Population estimates. 2008.

- 26.Reif SS, Whetten K, Wilson ER et al. HIV/AIDS in the Southern USA: a disproportionate epidemic. AIDS Care 2014;26:351–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foundation KF. Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map KFF.org, 2019:Medicaid Expansion by states. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gai Y, Marthinsen J. Medicaid Expansion, HIV Testing, and HIV-Related Risk Behaviors in the United States, 2010–2017. Am J Public Health 2019;109:1404–1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khatana SAM, Bhatla A, Nathan AS et al. Association of Medicaid Expansion With Cardiovascular Mortality. JAMA Cardiol 2019;4:671–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakala L. Breaking Down Mass Incarceration in the 2010 Census: State-by-State Incarceration Rates by Race/Ethnicity Prison Policy Reports, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Contextual factors and the black-white disparity in heterosexual HIV transmission. Epidemiology 2002;13:707–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang EA, Pletcher M, Lin F et al. Incarceration, incident hypertension, and access to health care: findings from the coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:687–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Howell BA, Long JB, Edelman EJ et al. Incarceration History and Uncontrolled Blood Pressure in a Multi-Site Cohort. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:1496–1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Statistics UBoL. Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2018. 2018.

- 35.Weiser SD, Frongillo EA, Ragland K, Hogg RS, Riley ED, Bangsberg DR. Food insecurity is associated with incomplete HIV RNA suppression among homeless and marginally housed HIV-infected individuals in San Francisco. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dupre ME, George LK, Liu G, Peterson ED. The cumulative effect of unemployment on risks for acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1731–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bureau UC. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014. 2014.

- 38.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol 2013;68:197–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spinelli MA, Hessol NA, Schwarcz S et al. Homelessness at diagnosis is associated with death among people with HIV in a population-based study of a US city. Aids 2019;33:1789–1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornelius T, Jones M, Merly C, Welles B, Kalichman MO, Kalichman SC. Impact of food, housing, and transportation insecurity on ART adherence: a hierarchical resources approach. AIDS Care 2017;29:449–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colasanti JA, Armstrong WS. Challenges of reaching 90-90-90 in the Southern United States. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2019;14:471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeffries WLt, Henny KD. From Epidemiology to Action: The Case for Addressing Social Determinants of Health to End HIV in the Southern United States. AIDS Behav 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emamzadeh-Fard S, Fard SE, SeyedAlinaghi S, Paydary K. Adherence to anti-retroviral therapy and its determinants in HIV/AIDS patients: a review. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2012;12:346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kent ST, Schwartz JE, Shimbo D et al. Race and sex differences in ambulatory blood pressure measures among HIV+ adults. J Am Soc Hypertens 2017;11:420–427.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson KK, Bokhour B, McInnes DK et al. Racial Disparities in HIV Care Extend to Common Comorbidities: Implications for Implementation of Interventions to Reduce Disparities in HIV Care. J Natl Med Assoc 2016;108:201–210.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramirez-Marrero FA, De Jesus E, Santana-Bagur J, Hunter R, Frontera W, Joyner MJ. Prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors in Hispanics living with HIV. Ethn Dis 2010;20:423–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chow FC, Wilson MR, Wu K, Ellis RJ, Bosch RJ, Linas BP. Stroke incidence is highest in women and non-Hispanic blacks living with HIV in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group Longitudinal Linked Randomized Trials cohort. Aids 2018;32:1125–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thakur KT, Lyons JL, Smith BR, Shinohara RT, Mateen FJ. Stroke in HIV-infected African Americans: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurovirol 2016;22:50–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feinstein MJ, Nance RM, Drozd DR et al. Assessing and Refining Myocardial Infarction Risk Estimation Among Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus: A Study by the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. JAMA Cardiol 2017;2:155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drozd DR, Kitahata MM, Althoff KN et al. Increased Risk of Myocardial Infarction in HIV-Infected Individuals in North America Compared With the General Population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2506–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Currier JS, Taylor A, Boyd F et al. Coronary heart disease in HIV-infected individuals. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003;33:506–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klein D, Hurley LB, Quesenberry CP Jr., Sidney S. Do protease inhibitors increase the risk for coronary heart disease in patients with HIV-1 infection? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;30:471–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Willig AL, Westfall AO, Overton ET et al. Obesity is associated with race/sex disparities in diabetes and hypertension prevalence, but not cardiovascular disease, among HIV-infected adults. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2015;31:898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong C, Gange SJ, Buchacz K et al. First Occurrence of Diabetes, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Hypertension Among North American HIV-Infected Adults, 2000–2013. Clin Infect Dis 2017;64:459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burkholder GA, Tamhane AR, Safford MM et al. Racial disparities in the prevalence and control of hypertension among a cohort of HIV-infected patients in the southeastern United States. PLoS One 2018;13:e0194940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riestenberg RA, Furman A, Cowen A et al. Differences in statin utilization and lipid lowering by race, ethnicity, and HIV status in a real-world cohort of persons with human immunodeficiency virus and uninfected persons. Am Heart J 2019;209:79–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oramasionwu CU, Hunter JM, Brown CM et al. Cardiovascular Disease in Blacks with HIV/AIDS in the United States: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Open AIDS J 2012;6:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gange SJ, Kitahata MM, Saag MS et al. Cohort profile: the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD). Int J Epidemiol 2007;36:294–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oramasionwu CU, Morse GD, Lawson KA, Brown CM, Koeller JM, Frei CR. Hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease in African Americans and whites with HIV/AIDS. Popul Health Manag 2013;16:201–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baumeister RF, & Leary MR. Writing narrative literature reviews. Review of general psychology 1997;1 311–320. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sardar MR, Badri M, Prince CT, Seltzer J, Kowey PR. Underrepresentation of women, elderly patients, and racial minorities in the randomized trials used for cardiovascular guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1868–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davis TC, Arnold CL, Mills G, Miele L. A Qualitative Study Exploring Barriers and Facilitators of Enrolling Underrepresented Populations in Clinical Trials and Biobanking. Front Cell Dev Biol 2019;7:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Group NMHSPTfAAC. The role of Community Advisory Boards (CABs) in Project Eban. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49 Suppl 1:S68–S74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mwinga A, Moodley K. Engaging with Community Advisory Boards (CABs) in Lusaka Zambia: perspectives from the research team and CAB members. BMC Med Ethics 2015;16:39–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levison JH, Levinson JK, Alegría M. A Critical Review and Commentary on the Challenges in Engaging HIV-Infected Latinos in the Continuum of HIV Care. AIDS and behavior 2018;22:2500–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fryer CS, Passmore SR, Maietta RC et al. The Symbolic Value and Limitations of Racial Concordance in Minority Research Engagement. Qual Health Res 2016;26:830–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoppe TA, Litovitz A, Willis KA et al. Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/black scientists. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaaw7238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cianelli R, Villegas N. Social Determinants of Health for HIV Among Hispanic Women. Hisp Health Care Int 2016;14:4–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Caiola C, Barroso J, Docherty SL. Black Mothers Living With HIV Picture the Social Determinants of Health. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2018;29:204–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Esenwa C, Ilunga Tshiswaka D, Gebregziabher M, Ovbiagele B. Historical Slavery and Modern-Day Stroke Mortality in the United States Stroke Belt. Stroke 2018;49:465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Peterson K, Anderson J, Boundy E, Ferguson L, McCleery E, Waldrip K. Mortality Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups in the Veterans Health Administration: An Evidence Review and Map. Am J Public Health 2018;108:e1–e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Okeke NL, Webel AR, Bosworth HB et al. Rationale and design of a nurse-led intervention to extend the HIV treatment cascade for cardiovascular disease prevention trial (EXTRA-CVD). Am Heart J 2019;216:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Petteway R, Mujahid M, Allen A, Morello-Frosch R. Towards a People’s Social Epidemiology: Envisioning a More Inclusive and Equitable Future for Social Epi Research and Practice in the 21st Century. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Akwanalo C, Njuguna B, Mercer T et al. Strategies for Effective Stakeholder Engagement in Strengthening Referral Networks for Management of Hypertension Across Health Systems in Kenya. Glob Heart 2019;14:173–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract 2005;6:134–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]