Abstract

Objective:

Two longitudinal studies examined whether effects of subjective norms on secondary cancer prevention behaviors were stronger and more likely to non-deliberative (i.e., partially independent of behavioral intentions) for African Americans (AAs) compared to European Americans (EAs), and whether the effects were moderated by racial identity.

Design:

Study 1 examined between-race differences in predictors of physician communication following receipt of notifications about breast density. Study 2 examined predictors of prostate cancer screening among AA men who had not been previously screened.

Main Outcome Measures:

Participants’ injunctive and descriptive normative perceptions; racial identity (Study 2); self-reported physician communication (Study 1) and PSA testing (Study 2) behaviors at follow up.

Results:

In Study 1, subjective norms were significantly associated with behaviors for AAs, but not for EAs. Moreover, there were significant non-deliberative effects of norms for AAs. In Study 2, there was further evidence of non-deliberative effects of subjective norms for AAs. Non-deliberative effects of descriptive norms were stronger for AAs who more strongly identified with their racial group.

Conclusion:

Subjective norms, effects of which are non-deliberative and heightened by racial identity, may be a uniquely robust predictor of secondary cancer prevention behaviors for AAs. Implications for targeted screening interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Subjective norms, African Americans, non-deliberative effects, cancer screening, secondary prevention

In the United States, African Americans (AAs) generally have the highest cancer incidence and mortality rates (DeSantis et al., 2016; O’Keefe, Meltzer, & Bethea, 2015; Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2017). The multifaceted correlates of these disparities - e.g., disadvantaged socioeconomic factors, worse access to health care, lower satisfaction with care (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2015; Lurie, Zhan, Sangl, Bierman, & Sekscenski, 2003; Tarraf, Jensen, & González, 2017) – are also associated with differences in cancer screening rates which ultimately contribute to disparities in incidence and mortality across a range of cancer sites (Ademuyiwa et al., 2011; The Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, 2008). Compelling evidence shows that cancer screening deficits lead to worse incidence and mortality outcomes for AAs for breast (Curtis, Quale, Haggstrom, & Smith-Bindman, 2008; Smith-Bindman et al., 2006; van Ravesteyn et al., 2011), prostate (Carpenter et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2008), and colorectal cancers (Lansdorp-Vogelaar et al., 2012). Hence, facilitating cancer screening among AAs is a critical means to address cancer health disparities. A greater understanding of psychological determinants of cancer screening behaviors among AAs can illuminate mechanisms that may be employed to facilitate cancer screening uptake. This current research examined how AAs’ perceptions of behavioral norms influenced cancer screening decision-making, and demonstrated that the effects of norms may be partially independent of AAs’ behavioral intentions (i.e., non-deliberative), and that racial identity moderated the effects norms on AAs’ cancer screening behaviors.

Subjective Norms and Behavior

The disheartening data about deficits in cancer screening rates among AAs, and related media narratives, likely influence subjective perceptions of behavioral norms (i.e., subjective norms) for African Americans. Extant literature supports the influence of subjective norms on subsequent behaviors (e.g., Ajzen, 1991; Cialdini, 2003; DeJong, 2010; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005), and recent research shows how subjective norms are related to preventive health behaviors such as condom use and sun protective behaviors (Lewis, Litt, Cronce, Blayney, & Gilmore, 2014; Reid & Aiken, 2013). For AAs’, compared to European Americans (EAs), subjective norms may matter more for health behavior decision-making. For example, subjective norms were the strongest predictor of breast feeding intentions for AA mothers (Bai, Wunderlich, & Fly, 2011). Compared to EAs, subjective norms were stronger predictors of teenagers’ smoking intentions (Hanson, 1997) and fruit and vegetable intake (Blanchard et al., 2009) for AAs. These findings suggest that subjective norms may play a similarly amplified role among AAs in the context of cancer screening behavioral decision-making.

Psychological Mechanism Relating Norms to Behavior

The role of subjective norms in behavioral decision-making is instrumental in contemporary behavioral prediction models. One such model, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB: Ajzen, 1991, 2011), provides the theoretical framework we used for this research. Briefly, TPB posits that attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intentions, which in turn influences actual behavior; hence, subjective norms are indirectly related to behaviors via behavioral intentions. Consistent with conceptualization of subjective norm in most decision-making theories (e.g., Cialdini, 2003; Lapinski & Rimal, 2005), TPB distinguishes two types of subjective norms: descriptive norms are individuals’ perceptions of what relevant others do, and injunctive norms are individuals’ perceptions of what relevant others want you to do (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010; Manning, 2009, 2011a, 2011b; McMillan & Conner, 2003; Sheeran & Orbell, 1999). The TPB has been used successfully to predict cancer screening behaviors (Griva, Anagnostopoulos, & Madoglou, 2009; Jennings-Dozier, 1999; Sieverding, Matterne, & Ciccarello, 2010; Tolma, Reininger, Evans, & Ureda, 2006), and is appropriate for examining the unique roles of injunctive and descriptive norms (collectively, subjective norms) in cancer screening behavioral decision-making among AAs.

Stronger Effects of Subjective Norms For African Americans

Our expectations of an amplified role of subjective norms for AAs are informed by social identity theory (SIT: Tajfel & Turner, 2004), the effects of racial identity salience, and the effects of greater collective self-concept. SIT posits that one’s group membership (i.e., social identity) influences her/his cognitions and behaviors. SIT-derived hypotheses, that people prefer in-group members whose behaviors are consistent with group norms (Hogg & Abrams, 1988; Hogg & Turner, 1987), have been empirically supported (e.g., Bettencourt et al., 2016; Marques, Abrams, Paez, & Martinez-Taboada, 1998; Marques & Yzerbyt, 1988; Marques, Yzerbyt, & Leyens, 1988). Relatedly, evidence shows that norms have stronger effects on behavior when a relevant identity is made salient (Byungjoo, Seungjun, & SangHyun, 2017; Reicher, 1984; Wellen, Hogg, & Terry, 1998); and, experiences of discrimination (Sanders Thompson, 1999), as well as contextual factors (Forehand, Deshpandé, & Reed Ii, 2002; Kenny & Briner, 2013; Shelton & Sellers, 2000; Steck, Heckert, & Heckert, 2003), can make racial identity more salient. Experiences of racial discrimination and race-based medical mistrust in contexts of medical interactions generally (Penner, Albrecht, Coleman, & Norton, 2007; Penner et al., 2009), and in cancer-related interactions specifically (Penner et al., 2012; Thompson, Valdimarsdottir, Jandorf, & Redd, 2003; Thompson, Valdimarsdottir, Winkel, Jandorf, & Redd, 2004), can heighten the salience of racial identity when AAs make decisions related to cancer screening. Finally, when individuals have more collectivist concept of the self (i.e., relatively greater weight of group membership in defining one’s self concept), subjective norms more will more strongly influence behavioral decisions (Trafimow & Finlay, 1996; Ybarra & Trafimow, 1998). Studies have shown that AAs are more collective in their self-concepts and afford greater centrality to ethnic identity compared to EAs (Avery, Tonidandel, Thomas, Johnson, & Mack, 2007; Gaines Jr., Larbie, Patel, Pereira, & Sereke-Melake, 2005; Gaines Jr., Marelich, Bledsoe, & Steers, 1997; Kern & Grandey, 2009; Marshall & Naumann, 2018). Altogether, these conditions are apt for subjective norms to have stronger effects on AAs’, compared to EAs’, screening decision-making.

The distinction between group norms as conceptualized by SIT (i.e., perceptions of normative behaviors for a group represented in one’s identity schema) and subjective norms as conceptualized by TPB (injunctive and descriptive behavioral perceptions of relevant others) warrants clarification. Typically, assessment of subjective norms prescribed by the TPB hold that salient referents influence normative perceptions. Depending on the behavior, salient identity-relevant groups can inform subjective norms and subsequent behaviors. For example, in a study of alcohol consumption behaviors among university military and veteran students, normative perceptions related to “typical students” influenced drinking behaviors whereas normative perceptions related to students in the military did not (Miller et al., 2016), suggesting that relevant others may be conceptualized as broader in-group.

Non-Deliberative Effect of Subjective Norms

TPB posits an indirect effect of injunctive and descriptive norms; however, some research provides evidence for a non-deliberative effect of norms on behavior – that is, a residual direct effect that is unmediated by deliberative behavioral intentions (Manning, 2009, 2011a, 2011b). This non-deliberative effect represents a more impulsive/automatic response to normative information, in contrast to a more reflective/conscious response (see Strack & Deutsch, 2004). We distinguish this conceptualization from prior research in that we focus on behaviors that are determined by deliberative intent, whereas most others have examined automaticity in the relation between normative perceptions and behaviors that were not determined by deliberative choice (Aarts & Dijksterhuis, 2003; Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Chartrand & Bargh, 1999; Dijksterhuis & Bargh, 2001) – see also Manning (2011a - footnote 1). A recent meta-analysis supported the non-deliberative effect of descriptive norms on health behaviors (McEachan et al., 2016). In that effects of subjective norms are often under detected (Nolan, Schultz, Cialdini, Goldstein, & Griskevicius, 2008), and thus arguably occur at least partially independent of conscious intent, we expected that heightened effects of subjective norms for AAs would manifest more via the non-deliberative route. Psychological (e.g., social motivation, self-control, effortful control, cognitive capacity) and contextual (e.g., more social behaviors) constructs have been shown to moderate the extent to which deliberative vs non-deliberative processes influenced behavior in relevant dual-process models (Grenard, Ames, & Stacy, 2013; Honkanen, Olsen, Verplanken, & Tuu, 2012; Manning, 2011a, 2011b; Pieters, Burk, Van der Vorst, Engels, & Wiers, 2014). We will examine whether racial group membership also moderates the non-deliberative effect of subjective norms.

Current Research

We examined support for our hypotheses with secondary analyses of two separate sets of data from our prior research. With the first study, we examined physician communication behaviors among women who were notified about a breast cancer risk factor. We expected that (H1) subjective norms would more strongly affect behaviors of AA women compared to EA women, and that (H2) the effect of subjective norms would be non-deliberative among AA women. With the second study, we further examined support for a non-deliberative effect of subjective norms on prostate cancer screening decision-making among AA men, and examined (H3) racial identity as a moderator of the effects of subjective norms.

Study 1: Normative Influences on Physician Communication

Data for Study 1 were from an examination of AA and EA Michigan women’s physician communication behaviors following notifications about breast density and breast cancer risk (Manning, Albrecht, O’Neill, & Purrington, 2018; Manning et al., 2017). Briefly, women with dense breasts are at increased breast cancer risk (Barlow et al., 2006; Boyd, Martin, Yaffe, & Minkin, 2011; McCormack & dos Santos Silva, 2006), and a recently adopted law in Michigan mandate that such women are notified of this on their mammogram report. These data were collected to examine between-race differences, and determinants of differences, in processes and outcomes related to subsequent physician communication following notification.

Method

Participants and procedures.

Participants were women with dense breasts, no prior breast cancer diagnoses, who presented for routine screening mammograms and whose screening results were negative (N = 557). Within two weeks of their mammograms, women participated in an initial survey investigating “opinions and perspective on some information that was included in your mammogram report”; three month later they were invited to participate in a follow-up survey assessing, among other things, whether they communicated with their physicians about the notifications. Participants completed the surveys online (Qualtrics, 2015), and received a $25 gift certificate for participation in each survey. The study was approved by Wayne State University’s Institutional Review Board.

Two hundred and seventy one women responded to the follow-up survey (49% response rate), of which there were 91 AAs (43%) and 121 EAs (57%) who comprised the sample for analysis. EA women were more likely to follow up than AA women (57% vs. 37%; χ2(1) = 19.42, p < .01); consequently, responders were higher income (d = 0.35), more educated (χ2(2) = 9.78, p < .01), and more likely to be married (χ2(2) = 8.83, p < .05) compared to non-responders. Of the analysis sample, most women (96%) women reported having health insurance. AA women were less likely married or partnered χ2(2) = 27.00, p < .01, less educated (χ2(5) = 14.29, p < .05) and had lower income ($40K to $49K vs. $90K to $99K, p < .01) than EA women.

Measures.

Relevant TPB predictors (i.e., attitudes, injunctive and descriptive norms, PBC and intentions) and sociodemographic descriptors were assessed with the initial survey, and behavior was assessed at follow-up.

TPB variables.

The behavioral target was “Talking to my doctor (i.e., primary care, ob/gyn, etc.) about the notification regarding the density of my breasts within the next three months…” Item responses were on a 7-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” (except for semantic differential attitude items), with some items reverse scored to address biased responding due to responder acquiescence. Two items assessed behavioral intentions (“I intend to talk…”, “I have decided that I will talk…”; r = .53, p < .001). Five semantic differential items (e.g., “Pleasant – unpleasant”, “Extremely good – extremely bad”; α = .83) assessed behavioral attitudes. Perceived behavioral control (PBC) was assessed with the item “Whether or not I talk… Injunctive norms were assessed with two items (e.g., “Most people I care about would expect me to talk…”, “Most people who are important to me would want me to talk…”; r = .58, p < .001). Descriptive norms were assessed with two items (e.g., “Most women who I care about would talk…”, “I could see most of the women who are important to me talking…”; r = .45, p < .001).” Behavior was assessed with Yes-No responses to the item “In the past three months, have you talked to your doctor (your primary care doctor, obstetrician/gynecologist, or whichever doctor you discuss women’s health with in particular) about the breast density notification you received with your last mammogram report.”

Prior BD Awareness.

We controlled for women’s prior awareness of their BD, which was assessed with Yes-No responses to the item “Prior to receiving your current mammogram report, did you know how dense your own breasts are?”

Planned analysis.

We fit a multigroup path model where racial group membership defined groups. Behavior was regressed onto prior BD awareness, intentions, PBC, and injunctive and descriptive norms (coefficients for norms represent non-deliberative effects). Intentions in turn were regressed onto attitude, PBC, injunctive and descriptive norms and prior BD awareness. We used lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) with R (R Core Team, 2016) to fit the path models. Given our relatively small sample size (Long, 1997; Moshagen & Musch, 2014), we used a linear probability model (Hellevik, 2009) fit via maximum likelihood estimation. We used chi-square difference tests to establish between-race differences in associations with behavior by comparing models in which the coefficients for the predictors of behavior were constrained to be equal (invariant model) vs freely estimated (variant model) between groups.

Results

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. AA women had more favorable attitudes, injunctive and descriptive normative perceptions and behavioral intentions; EA women were more likely to report being aware of their breast density prior to receiving notification.

Table 1:

Study 1: Descriptive statistics for AA and EA Women

| European Americans | Correlations | African Americans | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | N | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | M | SD | N | |||

| Prior BD Awareness**b | (1) | 0.60c | -- | 121 | -- | −.03 | −.13 | −.09 | .20 | .07 | .18 | (1) | 0.33c | -- | 90 |

| Attitude**a | (2) | 5.45 | 1.20 | 121 | −.21* | -- | .48** | .36** | −.05 | .48** | .03 | (2) | 5.93 | 1.07 | 87 |

| Injunctive Norm*a | (3) | 4.79 | 1.47 | 121 | −.16 | .58** | -- | .62** | −.07 | .52** | .05 | (3) | 5.32 | 1.66 | 91 |

| Descriptive Norm*a | (4) | 4.90 | 1.22 | 121 | −.08 | .49** | .50** | -- | .14 | .49** | .21* | (4) | 5.29 | 1.40 | 91 |

| PBC | (5) | 6.03 | 1.33 | 120 | .10 | .06 | .01 | .06 | -- | .27** | .00 | (5) | 5.90 | 1.37 | 91 |

| Behavioral Intentions**a | (6) | 5.00 | 1.57 | 121 | −.10 | .70** | .64** | .54** | .07 | -- | .05 | (6) | 5.63 | 1.37 | 91 |

| Behavior | (7) | 0.27c | -- | 121 | .00 | .23* | .18* | .23* | .10 | .31** | -- | (7) | 0.34c | -- | 91 |

Notes: BD = breast density, PBC = perceived behavioral control. Correlations above diagonal are for African Americans, and below the diagonal are European Americans. Lettered superscripts a and b indicate significant mean differences indicated by t-test and chi-square respectively; superscript c = proportion.

= p < .05

= p < .01

Model comparisons indicated that the coefficients predicting behavior were significantly different between EA and AA women (Δχ2(8) = 16.97, p < .05), and fit indices indicated good overall model fit for the variant model, χ2(2) = 0.07, ns; RMSEA = 0.00, 90% CI = 0.00 – 0.00; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; SRMR < .01. As seen in Table 2, attitudes, and both injunctive and descriptive norms were significant predictors of intention for all women, and PBC was a significant predictor of intentions only for AA women. Intentions were a significant predictor of behavior for EAs, whereas it was not for AAs. In contrast, descriptive norms were a significant predictor of behavior for AA women, demonstrating a significant non-deliberative effect of descriptive norms in support of H2. The total effect of descriptive norms on behavior was significant for AA women (estimate = 0.10, p < .01), whereas neither injunctive nor descriptive norms had significant total effects on behavior for EA women, demonstrating stronger effects of descriptive norms for AA women in partial support of H1.

Table 2:

Study 1: TPB path analysis results

| EA | AA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficients | SE | Coefficients | SE | |

| Behavior | ||||

| Intention | 0.08* | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 |

| PBC | 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.04 | 0.04 |

| INJN | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| DN | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.10* | 0.05 |

| Prior BD Awareness | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.21† | 0.11 |

| Intention | ||||

| Attitude | 0.58** | 0.10 | 0.39** | 0.12 |

| PBC | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.26** | 0.08 |

| INJN | 0.33** | 0.08 | 0.20* | 0.09 |

| DN | 0.22* | 0.09 | 0.18† | 0.10 |

| Prior BD Awareness | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.24 |

Notes: EA = European American, AA = African American. PBC = perceived behavioral control, INJN = injunctive norms, DN = descriptive norms, BD = breast density.

= p < .10

= p < .05

= p < .01.

Study 2: Racial Identity as a Moderator of Normative Influence

Prior research indicates that stronger identification with one’s in-group (i.e., group identity) is associated with greater in-group favoritism (e.g., Crisp & Beck, 2005; see Hewstone, Rubin, & Willis, 2002 for review) and stronger preferences for norm consistent behaviors among in-group members (Marques et al., 1988). Other research indicates that ethnic identity is more salient and central to AAs compared to EAs and other minority groups (Avery et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2014; Kern & Grandey, 2009; Marshall & Naumann, 2018; Utsey, Chae, Brown, & Kelly, 2002; Yoon, 2011). This heightened salience of racial identity for AAs supports our theoretical rationale for the stronger role of subjective norms on AAs’ behaviors. It also suggests that when we examine normative influence among AAs, both deliberative and non-deliberative effects of subjective norms may be stronger for AAs who more strongly identify with their racial group (H3). We examined this hypothesis in Study 2 with data from the control arm of a project examining the effects of a culturally targeted intervention on AA men’s prostate cancer screening intentions and behaviors.

Method

Participants and Procedure.

Eligible participants were English-speaking AA men between 40 and 75 years of age, with no history of prostate cancer, who lived or worked within the New York City (NYC) metropolitan area and reported no prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing in the prior six months. Participants (N = 197 after excluding 15 due to problems with consent forms, literacy, and missing data) completed self-administered questionnaires in groups (average size = 5) at local community sites (e.g., public libraries) from February 2006 to July 2007. At baseline, consented participants completed the baseline questionnaire and were then randomly assigned to receive either a culturally targeted brochure (N = 100) or a generic brochure published by the American Urological Association titled, Prostate Cancer Awareness for Men (N = 97). Since we had no hypotheses about the effects of targeted messages, only participants who received the generic brochure were included in these analyses. After reading the brochure, participants immediately completed a post-intervention questionnaire. Typically, these sessions lasted about 90 minutes. Participants were mailed a follow-up questionnaire six months later. Sixty one participants (63% of analysis sample) completed the follow-up, of whom 56 provided behavioral data described below. Follow-up responders did not differ from non-responders on any of the measures included in analyses. Participants were compensated $50 for their participation in the entire study.

Measures.

All TPB variables (PSA screening attitudes, injunctive and descriptive norms, perceived control, and intentions) were assessed at baseline and, with the exception of injunctive and descriptive norms, were repeated post-intervention. Subjective norms were excluded from the post-intervention survey as the targets of the intervention were attitudes and perceptions of control. We used the baseline assessments of subjective norms and post-intervention assessments of other TPB variables for hypothesis testing. Racial identity was assessed at baseline, and behaviors were assessed at follow-up.

TPB Variables.

The behavioral target was “[having] a PSA in the next 6–7 months.” Responses were assessed on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). We assessed both instrumental and affective components of attitudes. The mean of participants’ responses indicating whether they thought that getting a PSA would be worthwhile, reassuring, wise, healthy and important was used to assess instrumental attitudes (α =.95). The mean of participants’ responses indicating whether they thought getting a PSA would be worrying, embarrassing, and unpleasant (all reverse scored) assessed affective attitudes (α = .82). Injunctive norms were assessed with the mean of the items, “Most people who are important to you think you should be screened for prostate cancer” and “People who are important to you have encouraged you to be screened for prostate cancer,” (r = .65, p < .01). Descriptive norms were assessed with the mean of the items “I have talked to or heard from men who have been screened for prostate cancer” and “I have talked to or heard from men who benefit from regular prostate cancer screening,” (r = .83, p < .01). Whereas these items do not directly assess perceptions of what other men do with regards to screening behavior, they may be considered reasonable proxies in that responses to the items likely reflect perceptions of whether other men get screened. Perceived behavioral control was assessed with the item, “How much control do you have over getting a PSA?” Participants responded on a scale from 1 (Complete control) to 5 (No control) – responses were reverse coded so that higher numbers represented more control. Behavioral intentions were assessed with responses to the item “I intend to have a PSA in the next 6–7 months.” At the six-month follow-up, men who indicated that they had gotten, or were scheduled for, a PSA test since baseline were coded as engaging in PSA screening behaviors.

Racial Identity.

The 8-item centrality subscale of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI: Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997) was used to assess the extent to which race is a core component of self-concept (e.g., “In general, being Black is an important part of my self image.”). Participants responded on a scale from 1 to 4 (α = .66).

Planned analysis.

We took a similar linear probability approach to fit a path analysis with lavaan (Rosseel, 2012). We regressed intentions onto instrumental and affective attitudes; PBC; descriptive and injunctive norms; racial ID; and two-way interactions between each subjective norm and racial ID. We simultaneously regressed behaviors onto intentions, PBC, descriptive and injunctive norms, racial ID, and the two way interactions. To address potential multicollinearity and to facilitate interpretation of interactions, we used standardized values for the subjective norms and racial identity for model main effects and product interaction terms. We probed significant interactions with methods recommended by Preacher et al. (2006).

Results

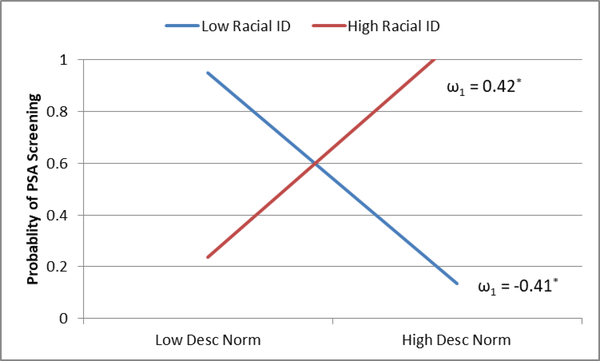

Means, SDs and correlations for study variables are presented in Table 3. Despite the small sample size, the final model exhibited decent fit (χ2(2) = 3.04, ns; RMSEA = 0.10, 90% CI = 0.00,0.30; SRMR = .02; CFI = 0.94). Path coefficients are presented in Table 4. Intentions were unrelated to subsequent 6-month behavior; hence, there were no significant indirect of subjective norms, despite a significant association between injunctive norms and intentions. A significant main effect of injunctive norms on behavior once again supported the non-deliberative effect of normative information for AAs. There was also a significant descriptive norms by racial ID interaction on behavior (illustrated in Figure 1). In support of H3, probing indicated a significant positive direct effect of descriptive norms on behavior when racial ID was high (≥ 2.4 SD above mean); additionally, there was a negative direct effect when racial ID was low (≤ 2.5 SD below mean). With deference to sample size, we tentatively probed the negative direct effect of descriptive norms for evidence of a suppressor effect by regressing behavior unto descriptive norms followed by injunctive norms in a stepwise fashion among AA men who were below median racial ID (N = 23). Whereas the descriptive norm coefficient was non-significant without injunctive norms in the model (b = −0.13, p > .25), it was marginally significant when injunctive norms was introduced (bdescriptive = −0.20, p = .07; binjunctive = 0.34, p = .02).

Table 3:

Study 2: Means, SD and correlations for study variables

| M | SD | r | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| 1 | Instrumental Attitude | 4.58 | 0.47 | |||||||

| 2 | Affective Attitude | 3.81 | 0.95 | 0.13 | ||||||

| 3 | Descriptive Norms | 3.08 | 1.31 | 0.16 | 0.17 | |||||

| 4 | Injunctive Norms | 3.71 | 0.96 | 0.21 | −0.02 | 0.16 | ||||

| 5 | PBC | 4.43 | 0.99 | −0.01 | .45** | 0.25† | −0.02 | |||

| 6 | Intentions | 3.66 | 1.08 | .29* | 0.12 | 0.23† | .39** | 0.07 | ||

| 7 | Racial ID | 2.92 | 0.44 | 0.10 | −0.16 | −0.04 | −0.25† | −0.16 | 0.01 | |

| 8 | PSA Behavior | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.08 | .42** | −0.07 | 0.25† | −0.08 |

Notes: PBC = perceived behavioral control.

= p < .10

= p < .05

= p < .01.

a = proportion

Table 4:

Study 2: Path analyses results

| Coefficients | SE | |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior | ||

| Intentions | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| PBC | −0.05 | 0.06 |

| Descriptive Normsz | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Injunctive Normz | 0.23** | 0.07 |

| Racial IDz | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Descriptive Norms by Racial ID | 0.14* | 0.06 |

| Injunctive Norm by Racial ID | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| Intentions | ||

| Instrumental Attitudes | 0.37 | 0.29 |

| Affective Attitudes | 0.10 | 0.15 |

| PBC | 0.03 | 0.15 |

| Descriptive Normsz | 0.12 | 0.14 |

| Injunctive Normz | 0.44** | 0.15 |

| Racial IDz | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Descriptive Norms by Racial ID | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Injunctive Norm by Racial ID | −0.08 | 0.14 |

Notes: PBC = perceived behavioral control.

= p < .01

= p < .05

= p < .10. Subscript z = standardized.

Figure 1:

Study 2: Influence of racial identity on direct effect of descriptive norms on PSA screening behavior. Low Racial ID = −3 SD, High racial ID = 3 SD. ω1 = simple slope.* = p < .05.

Discussion

Our data provide preliminary support for the amplified role of subjective norms in AAs behavioral decision making related to secondary cancer prevention behaviors, and is the first to show that racial group membership moderates non-deliberative effects of subjective norms. Results from Study 1 partially supported our hypothesis that subjective norms have stronger effects on behaviors for AAs compared to EAs; specifically, there was a significant total effect of descriptive norms for AA, but not for EA women. Results from both studies supported our hypothesis regarding a significant non-deliberative effect of subjective norms on behaviors for AAs. Specifically, descriptive norms directly predicted physician communication about breast density notifications for AA women, and both injunctive and descriptive norms directly predicted PSA testing behaviors for AA men. In partial support of our hypothesis regarding the effects of racial identity however, the non-deliberative effect of descriptive norms on PSA testing behaviors was only present when men more strongly identified as AAs. These findings suggest a gender difference in the non-deliberative effect of injunctive norms since there was no significant direct effect of injunctive norms on physician communication for AA women; however, future research should examine these potential gender differences among secondary prevention behaviors applicable to both men and women (e.g., colorectal cancer screening).

Racial identity did not influence the non-deliberative effects of injunctive norms; however, our hypothesis was partially supported for the non-deliberative effects of descriptive norms. An inverse effect of descriptive norms on PSA testing behaviors was noted among AA men for whom racial identity was low. Probing this effect among AA men with weaker racial ID indicated evidence of a positive suppressor effect (i.e., where the introduction of a subsequent predictor suppresses unexplained variance in the association between a prior predictor and the outcome, thus strengthening the coefficient for the prior predictor). Suppressor effects, and moderation of suppressor effects, have been documented in other research using TPB to examine the joint effects of descriptive and injunctive norms (Manning, 2009, 2011b; Manning, Wojda, et al., 2016) – we demonstrated similar suppression moderated by racial identity, and demonstrated a negative effect of descriptive norms in the context of that suppression. We speculate that this effect represents an outcome of psychological reactance (Rosenberg & Siegel, 2018; Steindl, Jonas, Sittenthaler, Traut-Mattausch, & Greenberg, 2015) among weakly racially identified AA men. For those with similar perceptions of descriptive norms, stronger perceptions of injunctive norms will be associated with stronger inverse associations between descriptive norms and behavior. In other words, this represents a manifestation of weakly identified AA men’s reactance to group-relevant descriptive norms as behavioral injunctions increase. A recent study attributed a similar negative effect of normative perceptions on cancer screening behaviors to psychological reactance (Sieverding et al., 2010). For our study, the items assessing norms referred to “most people who are important to me”, and did not mention anything about racial group (e.g., “Black people whose opinions matter to me…”). However, given the racially homogenous small groups in which the data were collected, and the presence of other items on the survey assessing race-related constructs, it is likely that race was salient when responding to survey items, thus priming the contexts for those men inclined to reactance. When AA men strongly identified with their racial group, no similar reactance was evident given a direct effect of descriptive norms on PSA testing behaviors. This is likely due to stronger motivations for group norm-consistent behaviors for individuals with stronger group identities (Crisp & Beck, 2005; Marques et al., 1988). Future research should examine whether the moderating effects of racial identity are equivalent for men and women using screening behaviors applicable to both.

Whereas most cancer screening behaviors are similar in that they may be influenced by perceptions of relevant constructs such as cancer fatalism, cancer risk perceptions, and knowledge (Manning, Purrington, Penner, Duric, & Albrecht, 2016; Manning, Wojda, et al., 2016; Mitchell, Manning, Shires, Chapman, & Burnett, 2014), they differ in other attributes. Variation in attributes of behaviors have been shown to moderate both the deliberative and non-deliberative effects of subjective norms and behaviors (Lapinski & Rimal, 2005; Manning, 2011a; Rimal, Lapinski, Turner, & Smith, 2011). Similarly, variation in attributes associated with cancer screening behaviors likely influence the associations between norms and behaviors. For example, for some individuals, salience of the discomfort associated with mammography and aversion to some CRC screening modalities may attenuate the effects of subjective norms on behavioral decision-making (Hawley et al., 2008; Kurtz, Given, Given, & Kurtz, 1993; Nadalin, Maher, Lessels, Chiarelli, & Kreiger, 2016; Watts, Vernon, Myers, & Tilley, 2003) more so than, for example, the relative ease associated with PSA tests. Variability in uncertainty given changes in screening guidelines, and uncertainty about the utility of screening to prevent cancer-related death, may also influence the extent to which individuals deliberatively or non-deliberatively use normative information for screening decision making (Manning, 2009). We currently lack a theoretically refined model of how variability among behaviors moderates normative influence; however, ongoing topical research (Manning, 2011a; Rimal et al., 2011) shows promise for such a model and its applications to health behaviors.

Interventions to increase cancer screening intentions and behaviors among AAs are important tools to address disparities in cancer incidence and mortality. Targeted interventions have been disseminated via multiple modalities such as patient navigators, peer-to-peer in community organizations, and print-based and computer-based media (Leone et al., 2013; Philip, DuHamel, & Jandorf, 2010; Rawl et al., 2012; Rogers, Goodson, Dietz, & Okuyemi, 2016; Sly, Edwards, Shelton, & Jandorf, 2013). Given the heightened role of subjective norms in cancer screening behavioral decision-making for AAs, normative messages could be effectively used in such targeted and tailored messages to promote cancer screening among AAs. This may be particularly effective in light of the unique influence of non-deliberative effects of norms among AAs demonstrated here, and given that norms have been shown to influence behaviors even when recipients of norm-based interventions did not perceive that they would (Nolan et al., 2008). In the area of cancer prevention, we only identified one study that used a social norms marketing approach to improve sun protective behaviors by influencing normative perceptions (Reid & Aiken, 2013). Given the relationship between screening behaviors and disparities in cancer incidence and mortality (The Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities, 2008), the potential that normative perceptions may serve as an efficacious focus for targeted intervention for AAs provides rationale and motivation for further investigations.

Interventions that target normative perceptions should consider two contemporary issues that may influence perceptions of screening behaviors among AAs. First, despite the historically lower screening rates for AAs compared to EAs, recent data suggest that cancer screening rates have converged for women. For example, data show that rates of breast and cervical cancer screening converged and were becoming slightly higher for AA women compared to EA women (American Cancer Society, 2017; Hewitt, Devesa, & Breen, 2004) and some evidence showed attenuations in racial differences in breast and colorectal cancer screening for women, but not for men (Rao, Breen, & Graubard, 2016). Second, some studies suggest that racial differences in cancer screening rates were largely due to sociodemographic variables such as income, education and health insurance status (Doubeni et al., 2010; Fisher et al., 2004; O’Malley, Forrest, Feng, & Mandelblatt, 2005). In some cases, AA cancer screening disparities were attenuated or even reversed when sociodemographic variables were accounted for (Rakowski, Clark, Rogers, & Weitzen, 2009; Rakowski, Clark, Rogers, & Weitzen, 2011). These data challenge some narratives regarding lower cancer screening rates among AAs, and such challenges may indirectly influence normative perceptions of screening behaviors. Studies that examine discrepancies between actual and perceived cancer screening rates for AAs could have considerably applicability and overlap with research examining how norm-based interventions may further improve cancer screening rates.

These data are limited by the fact that the studies were not explicitly designed to test hypotheses about normative perceptions and cancer screening behaviors among AAs. Nonetheless, these data presented an opportunity to examine our hypotheses given that they all had similarly operationalized constructs consistent with the TPB. Future research should be designed explicitly to further examine between-race differences in the influence of subjective norms in behavioral decision-making related to cancer screening behaviors, and to elucidate the mechanisms and moderators involved in the heightened effects of norms among AAs.

References

- Aarts H, & Dijksterhuis A (2003). The silence of the library: Environment, situational norm, and social behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(1), 18–28. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.1.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ademuyiwa FO, Edge SB, Erwin DO, Orom H, Ambrosone CB, & Underwood W 3rd. (2011). Breast cancer racial disparities: unanswered questions. Cancer Research, 71(3), 640–644. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I (2011). The theory of planned behaviour: Reactions and reflections. Psychology & Health, 26(9), 1113–1127. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2011.613995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2017). Cancer Prevention & Early Detection Facts & Figures, 2017–2018. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures/cancer-prevention-and-early-detection-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf

- Avery DR, Tonidandel S, Thomas KM, Johnson CD, & Mack DA (2007). Assessing the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure for measurement equivalence across racial and ethnic groups. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 67(5), 877–888. doi: 10.1177/0013164406299105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai Y, Wunderlich SM, & Fly AD (2011). Predicting intentions to continue exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months: A comparison among racial/ethnic groups. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(8), 1257–1264. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0703-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, & Chartrand TL (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. American Psychologist, 54(7), 462–479. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow WE, White E, Ballard-Barbash R, Vacek PM, Titus-Ernstoff L, Carney PA, . . . Kerlikowske K (2006). Prospective breast cancer risk prediction model for women undergoing screening mammography. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 98(17), 1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettencourt BA, Manning M, Molix L, Schlegel R, Eidelman S, & Biernat M (2016). Explaining Extremity in Evaluation of Group Members: Meta-Analytic Tests of Three Theories. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(1), 49–74. doi: 10.1177/1088868315574461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard CM, Kupperman J, Sparling PB, Nehl E, Rhodes RE, Courneya KS, & Baker F (2009). Do ethnicity and gender matter when using the theory of planned behavior to understand fruit and vegetable consumption? Appetite, 52(1), 15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NF, Martin LJ, Yaffe MJ, & Minkin S (2011). Mammographic density and breast cancer risk: current understanding and future prospects. Breast Cancer Research, 13(6), 223–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SD, Unger Hu KA, Mevi AA, Hedderson MM, Shan J, Quesenberry CP, & Ferrara A (2014). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure—Revised: Measurement invariance across racial and ethnic groups. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 154–161. doi: 10.1037/a0034749.supp (Supplemental) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byungjoo C, Seungjun A, & SangHyun L (2017). Construction Workers’ Group Norms and Personal Standards Regarding Safety Behavior: Social Identity Theory Perspective. Journal of Management in Engineering, 33(4), 1–11. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WR, Howard DL, Taylor YJ, Ross LE, Wobker SE, & Godley PA (2010). Racial differences in PSA screening interval and stage at diagnosis. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 21(7), 1071–1080. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9535-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartrand TL, & Bargh JA (1999). The chameleon effect: The perception-behavior link and social interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(6), 893–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini RB (2003). Crafting normative messages to protect the environment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 105–109. doi: 10.1111/1467-8721.01242 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp RJ, & Beck SR (2005). Reducing Intergroup Bias: The Moderating Role of Ingroup Identification. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8(2), 173–185. doi: 10.1177/1368430205051066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis E, Quale C, Haggstrom D, & Smith-Bindman R (2008). Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: How much is explained by screening, tumor severity, biology, treatment, comorbidities, and demographics? Cancer, 112(1), 171–180. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W (2010). Social norms marketing campaigns to reduce campus alcohol problems. Health Communication, 25(6–7), 615–616. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.496845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, & Proctor BD (2015). Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014 (P60–252). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-252.html

- DeSantis CE, Siegel RL, Sauer AG, Miller KD, Fedewa SA, Alcaraz KI, & Jemal A (2016). Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2016: Progress and opportunities in reducing racial disparities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 66(4), 290–308. doi: 10.3322/caac.21340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijksterhuis A, & Bargh JA (2001). The perception-behavior expressway: Automatic effects of social perception on social behavior In Zanna MP (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology, Vol. 33 (pp. 1–40). San Diego, CA US: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Klabunde CN, Young AC, Field TS, & Fletcher RH (2010). Racial and ethnic trends of colorectal cancer screening among Medicare enrollees. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38(2), 184–191. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. New York, NY US: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher DA, Dougherty K, Martin C, Galanko J, Provenzale D, & Sandler RS (2004). Race and colorectal cancer screening: a population-based study in North Carolina. North Carolina Medical Journal, 65(1), 12–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand MR, Deshpandé R, & Reed Ii A (2002). Identity Salience and the Influence of Differential Activation of the Social Self-Schema on Advertising Response. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1086–1099. doi: 10.1037//3021-9010.87.6.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines SO Jr., Larbie J, Patel S, Pereira L, & Sereke-Melake Z (2005). Cultural Values Among African-Descended Persons in the United Kingdom: Comparisons With European-Descended and Asian-Descended Persons. Journal of Black Psychology, 31(2), 130–151. doi: 10.1177/0095798405274720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines SO Jr., Marelich WD, Bledsoe KL, & Steers WN (1997). Links between race/ethnicity and cultural values as mediated by racial/ethnic identity and moderated by gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(6), 1460–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Ames SL, & Stacy AW (2013). Deliberative and spontaneous cognitive processes associated with HIV risk behavior. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(1), 95–107. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9404-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griva F, Anagnostopoulos F, & Madoglou S (2009). Mammography screening and the theory of planned behavior: Suggestions toward an extended model of prediction. Women & Health, 49(8), 662–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MJS (1997). The theory of planned behavior applied to cigarette smoking in African-American, Puerto Rican, and non-Hispanic White teenage females. Nursing Research, 46(3), 155–162. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199705000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley ST, Volk RJ, Krishnamurthy P, Jibaja-Weiss M, Vernon SW, & Kneuper S (2008). Preferences for colorectal cancer screening among racially/ethnically diverse primary care patients. Medical Care, 46(9,Suppl1), S10–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellevik O (2009). Linear versus logistic regression when the dependent variable is a dichotomy. Quality & Quantity: International Journal of Methodology, 43(1), 59–74. doi: 10.1007/s11135-007-9077-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Devesa SS, & Breen N (2004). Cervical cancer screening among U.S. women: analyses of the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Preventive Medicine, 39(2), 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewstone M, Rubin M, & Willis H (2002). Intergroup bias. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 575–604. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, & Abrams D (1988). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. Florence, KY, US: Taylor & Frances/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg MA, & Turner JC (1987). Social identity and conformity: A theory of referent information influence In Doise W, Moscovici S, Doise W, & Moscovici S (Eds.), Current issues in European social psychology, Vol. 2 (pp. 139–182). New York, NY, US; Paris, France: Cambridge University Press Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme. [Google Scholar]

- Honkanen P, Olsen SO, Verplanken B, & Tuu HH (2012). Reflective and impulsive influences on unhealthy snacking. The moderating effects of food related self-control. Appetite, 58(2), 616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings-Dozier K (1999). Predicting intentions to obtain a pap smear among African American and Latina women: Testing the theory of planned behavior. Nursing Research, 48(4), 198–205. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199907000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BA, Liu W-L, Araujo AB, Kasl SV, Silvera SN, Soler-Vilá H, . . . Dubrow R (2008). Explaining the race difference in prostate cancer stage at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication Of The American Association For Cancer Research, Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology, 17(10), 2825–2834. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny EJ, & Briner RB (2013). Increases in salience of ethnic identity at work: The roles of ethnic assignation and ethnic identification. Human Relations, 66(5), 725–748. doi: 10.1177/0018726712464075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kern JH, & Grandey AA (2009). Customer incivility as a social stressor: The role of race and racial identity for service employees. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(1), 46–57. doi: 10.1037/a0012684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz ME, Given B, Given CW, & Kurtz JC (1993). Relationships of barriers and facilitators to breast self-examination, mammography, and clinical breast examination in a worksite population. Cancer Nursing, 16(4), 251–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, van Ballegooijen M, Zauber AG, & Jemal A (2012). Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication Of The American Association For Cancer Research, Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology, 21(5), 728–736. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-12-0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapinski MK, & Rimal RN (2005). An Explication of Social Norms. Communication Theory, 15(2), 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Leone LA, Reuland DS, Lewis CL, Ingle M, Erman B, Summers TJ, . . . Pignone MP (2013). Reach, usage, and effectiveness of a Medicaid patient navigator intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening, Cape Fear, North Carolina, 2011. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, E82–E82. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.120221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Litt DM, Cronce JM, Blayney JA, & Gilmore AK (2014). Underestimating protection and overestimating risk: Examining descriptive normative perceptions and their association with drinking and sexual behaviors. Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 86–96. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.710664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JS (1997). Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables (Vol. 7). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lurie N, Zhan C, Sangl J, Bierman AS, & Sekscenski ES (2003). Variation in racial and ethnic differences in consumer assessments of health care. American Journal of Managed Care, 9(7), 502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M (2009). The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 649–705. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M (2011a). When normative perceptions lead to actions: Behavior-level attributes influence the non-deliberative effects of subjective norms on behavior. Social Influence, 6(4), 212–230. doi: 10.1080/15534510.2011.618594 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M (2011b). When we do what we see: The moderating role of social motivation on the relation between subjective norms and behavior in the theory of planned behavior. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 33(4), 351–364. doi: 10.1080/01973533.2011.589304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Albrecht TL, O’Neill S, & Purrington K (2018). Between-Race Differences In Supplemental Breast Cancer Screening Before And After Breast Density Notification Law. Journal Of The American College Of Radiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Albrecht TL, Yilmaz-Saab Z, Penner L, Norman A, & Purrington K (2017). Explaining between-race differences in African-American and European-American women’s responses to breast density notification. Social Science & Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Purrington K, Penner L, Duric N, & Albrecht TL (2016). Between-race differences in the effects of breast density information and information about new imaging technology on breast-health decision-making. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(6), 1002–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Wojda M, Hamel L, Salkowski A, Schwartz AG, & Harper FW (2016). Understanding the role of family dynamics, perceived norms, and lung cancer worry in predicting second-hand smoke avoidance among high-risk lung cancer families. Journal of Health Psychology. doi: 10.1177/1359105316630132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques JM, Abrams D, Paez D, & Martinez-Taboada C (1998). The role of categorization and in-group norms in judgments of groups and their members. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(4), 976–988. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.75.4.976 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marques JM, & Yzerbyt VY (1988). The black sheep effect: Judgmental extremity towards ingroup members in inter- and intra-group situations. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(3), 287–292. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420180308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marques JM, Yzerbyt VY, & Leyens J-P (1988). The ‘Black Sheep Effect’: Extremity of judgments towards ingroup members as a function of group identification. European Journal of Social Psychology, 18(1), 1–16. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420180102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SR, & Naumann LP (2018). What’s your favorite music? Music preferences cue racial identity. Journal of Research in Personality, 76, 74–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2018.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack VA, & dos Santos Silva I (2006). Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 15(6), 1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachan R, Taylor N, Harrison R, Lawton R, Gardner P, & Conner M (2016). Meta-analysis of the reasoned action approach (RAA) to understanding health behaviors. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 50(4), 592–612. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9798-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan B, & Conner M (2003). Applying an Extended Version of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Illicit Drug Use Among Students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(8), 1662–1683. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Brett EI, Leavens EL, Meier E, Borsari B, & Leffingwell TR (2016). Informing alcohol interventions for student service members/veterans: Normative perceptions and coping strategies. Addictive Behaviors, 57, 76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JA, Manning M, Shires D, Chapman RA, & Burnett J (2014). Fatalistic Beliefs About Cancer Prevention Among Older African American Men. Research on Aging. doi: 10.1177/0164027514546697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshagen M, & Musch J (2014). Sample size requirements of the robust weighted least squares estimator. Methodology: European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, 10(2), 60–70. doi: 10.1027/1614-2241/a000068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadalin V, Maher J, Lessels C, Chiarelli A, & Kreiger N (2016). Breast screening knowledge and barriers among under/never screened women. Public Health, 133, 63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan JM, Schultz PW, Cialdini RB, Goldstein NJ, & Griskevicius V (2008). Normative social influence is underdetected. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 913–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley AS, Forrest CB, Feng S, & Mandelblatt J (2005). Disparities despite coverage: gaps in colorectal cancer screening among Medicare beneficiaries. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(18), 2129–2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe EB, Meltzer JP, & Bethea TN (2015). Health Disparities and Cancer: Racial Disparities in Cancer Mortality in the United States, 2000–2010. Frontiers in Public Health, 3, 51. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Albrecht TL, Coleman DK, & Norton WE (2007). Interpersonal Perspectives on Black–White Health Disparities: Social Policy Implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 1(1), 63–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2007.00004.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Edmondson D, Dailey RK, Markova T, Albrecht TL, & Gaertner SL (2009). The experience of discrimination and black-white health disparities in medical care. Journal of Black Psychology, 35(2), 180–203. doi: 10.1177/0095798409333585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Eggly S, Griggs JJ, Underwood W III, Orom H, & Albrecht TL (2012). Life-threatening disparities: The treatment of Black and White cancer patients. Journal of Social Issues, 68(2), 328–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01751.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip EJ, DuHamel K, & Jandorf L (2010). Evaluating the impact of an educational intervention to increase CRC screening rates in the African American community: a preliminary study. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 21(10), 1685–1691. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9597-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters S, Burk WJ, Van der Vorst H, Engels RC, & Wiers RW (2014). Impulsive and reflective processes related to alcohol use in young adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational Tools for Probing Interactions in Multiple Linear Regression, Multilevel Modeling, and Latent Curve Analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(3), 437. [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. (2015). Qualtrics Provo, Utah. Retrieved from http://www.qualtrics.com

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Clark MA, Rogers ML, & Weitzen S (2009). Investigating reversals of association for utilization of recent mammography among Hispanic and Non-Hispanic Black women. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 20(8), 1483–1495. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9345-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Clark MA, Rogers ML, & Weitzen SH (2011). Reversals of association for Pap, colorectal, and prostate cancer testing among Hispanic and non-Hispanic black women and men. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication Of The American Association For Cancer Research, Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology, 20(5), 876–889. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-10-1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao SR, Breen N, & Graubard BI (2016). Trends in Black-White Disparities in Breast and Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates in a Changing Screening Environment: The Peters-Belson Approach Using United States National Health Interview Surveys 2000–2010. Medical Care, 54(2), 133–139. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawl SM, Skinner CS, Perkins SM, Springston J, Wang H-L, Russell KM, . . . Champion VL (2012). Computer-delivered tailored intervention improves colon cancer screening knowledge and health beliefs of African-Americans. Health Education Research, 27(5), 868–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reicher SD (1984). Social influence in the crowd: Attitudinal and behavioural effects of de-individuation in conditions of high and low group salience. British Journal of Social Psychology, 23(4), 341–350. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1984.tb00650.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reid AE, & Aiken LS (2013). Correcting injunctive norm misperceptions motivates behavior change: A randomized controlled sun protection intervention. Health Psychology, 32(5), 551–560. doi: 10.1037/a0028140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal RN, Lapinski MK, Turner MM, & Smith KC (2011). The Attribute-Centered Approach for Understanding Health Behaviors: Initial Ideas and Future Research Directions. Studies in Communication Sciences, 11(1), 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers CR, Goodson P, Dietz LR, & Okuyemi KS (2016). Predictors of Intention to Obtain Colorectal Cancer Screening Among African American Men in a State Fair Setting. American Journal Of Men’s Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg BD, & Siegel JT (2018). A 50-year review of psychological reactance theory: Do not read this article. Motivation Science, 4(4), 281–300. doi: 10.1037/mot0000091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel Y (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders Thompson VL (1999). Variables affecting racial-identity salience among African Americans. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139(6), 748–761. doi: 10.1080/00224549909598254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, & Orbell S (1999). Augmenting the theory of planned behavior: Roles for anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(10), 2107–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JN, & Sellers RM (2000). Situational stability and variability in African American racial identity. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(1), 27–50. doi: 10.1177/0095798400026001002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A (2017). Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67(1), 7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieverding M, Matterne U, & Ciccarello L (2010). What role do social norms play in the context of men’s cancer screening intention and behavior? Application of an extended theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology, 29(1), 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sly JR, Edwards T, Shelton RC, & Jandorf L (2013). Identifying barriers to colonoscopy screening for nonadherent African American participants in a patient navigation intervention. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication Of The Society For Public Health Education, 40(4), 449–457. doi: 10.1177/1090198112459514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, Abraham L, Barbash RB, Strzelczyk J, . . . Kerlikowske K (2006). Does utilization of screening mammography explain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Annals of Internal Medicine, 144(8), 541–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck LW, Heckert DM, & Heckert DA (2003). The salience of racial identity among African-American and white students. Race & Society, 6(1), 57–73. doi: 10.1016/j.racsoc.2004.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steindl C, Jonas E, Sittenthaler S, Traut-Mattausch E, & Greenberg J (2015). Understanding Psychological Reactance: New Developments and Findings. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 223(4), 205–214. doi: 10.1027/2151-2604/a000222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack F, & Deutsch R (2004). Reflective and Impulsive Determinants of Social Behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 8(3), 220–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner JC (2004). The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior In Jost JT & Sidanius J (Eds.), Political psychology: Key readings. (pp. 276–293): Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tarraf W, Jensen G, & González HM (2017). Patient Centered Medical Home Care Among Near-Old and Older Race/Ethnic Minorities in the US: Findings from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(6), 1271–1280. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0491-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. (2008, March 11). Cancer Health Disparities Fact Sheet. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-nci/organization/crchd/cancer-health-disparities-fact-sheet

- Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Jandorf L, & Redd W (2003). Perceived disadvantages and concerns about abuses of genetic testing for cancer risk: Differences across African American, Latina and Caucasian women. Patient Education and Counseling, 51(3), 217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00219-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, & Redd W (2004). The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: Psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Preventive Medicine, 38(2), 209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolma EL, Reininger BM, Evans A, & Ureda J (2006). Examining the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Construct of Self-Efficacy to Predict Mammography Intention. Health Education & Behavior, 33(2), 233–251. doi: 10.1177/1090198105277393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafimow D, & Finlay KA (1996). The importance of subjective norms for a minority of people: Between-subjects and within-subjects analyses. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(8), 820–828. [Google Scholar]

- Utsey SO, Chae MH, Brown CF, & Kelly D (2002). Effect of ethnic group membership on ethnic identity, race-related stress, and quality of life. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(4), 366–377. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.8.4.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ravesteyn NT, Schechter CB, Near AM, Heijnsdijk EAM, Stoto MA, Draisma G, . . . Mandelblatt JS (2011). Race-specific impact of natural history, mammography screening, and adjuvant treatment on breast cancer mortality rates in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication Of The American Association For Cancer Research, Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology, 20(1), 112–122. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts BG, Vernon SW, Myers RE, & Tilley BC (2003). Intention to be screened over time for colorectal cancer in male automotive workers. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication Of The American Association For Cancer Research, Cosponsored By The American Society Of Preventive Oncology, 12(4), 339–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen JM, Hogg MA, & Terry DJ (1998). Group norms and attitude–behavior consistency: The role of group salience and mood. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 2(1), 48–56. doi: 10.1037/1089-2699.2.1.48 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra O, & Trafimow D (1998). How priming the private self or collective self affects the relative weights of attitudes and subjective norms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(4), 362–370. doi: 10.1177/0146167298244003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E (2011). Measuring ethnic identity in the Ethnic Identity Scale and the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure-Revised. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17(2), 144–155. doi: 10.1037/a0023361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]