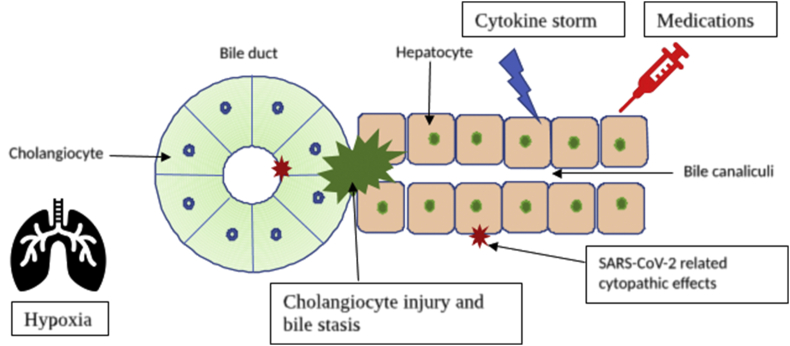

We read the article by Agarwal et al1 with great interest about the liver injury in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The precise mechanism of liver injury is still unclear. These abnormalities could be due to virus-related cytopathic effects or nonviral causes such as cytokine storm, hypoxia, and hepatotoxic medications2 (Figure 1). There are no peer-reviewed published research articles on the pathogenesis of liver injury, and the pandemic has led to an unprecedented surge in preprint publications on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. We sought relevant scientific studies regarding liver injury by the SARS-CoV-2 virus in four public preprint repositories (i.e., medRxiv, bioRxiv, arXiv, and Social Science Research Network). Three preliminary scientific articles explored the mechanisms of liver injury in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis of COVID-19–related hepatopathy. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

SARS-CoV-2 enters cells through angiotensin-converting enzyme–related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) receptors and is facilitated by transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2). Single sequence RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data in healthy liver tissues from two independent cohorts demonstrated that ACE2 is mainly expressed on cholangiocytes (59.7%) but not in hepatocytes (2.6%).3 Besides, the highest levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 were coexpressed in TROP2high cholangiocyte–biased progenitor cells of the liver.4 Conversely, these studies did not explore specific mechanisms of cholangiocyte injury, ACE2 independent hepatocyte infection, and intrinsic antiviral responses. The results suggest that SARS-CoV-2 infection of the cholangiocytes and progenitor cell population might compromise the regenerative capabilities of the liver.

Furthermore, Guan et al5 explored the expression changes of ACE2 and performed RNA-seq analysis of gene expression changes in the liver remnant of the hepatectomy mouse model at different time points. mRNA levels of ACE2 were upregulated during maximum hepatocyte proliferation and returned to normal with the stoppage of hepatocyte regeneration. In addition, TROP2 protein expression was upregulated explicitly in mouse and rat injury models with oval cell activation.6 The authors hypothesized that the ACE2 expression on cholangiocytes might have retained on some of the neohepatocytes during liver regeneration after hepatic injury, and these neohepatocytes are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Another study explored the mechanisms of liver injury SARS-CoV-2 infection of cholangiocytes in a human liver ductal organoid model.7 The cholangiocytes in the model were permissible for SARS-CoV-2 infection and supported the viral replication. The infection also ablated the tight junction protein, claudin 1, and significantly reduced the expression of bile acid transporters, apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporters (ASBT), and cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulators (CFTR). These changes in cholangiocytes could be due to the modulation of gene expression by SARS-CoV-2 infection. The study suggests that the liver injury in COVID-19 might be partly due to direct injury of cholangiocytes and subsequent accumulation of bile acids by the SARS-CoV-2 infection. The temporary damage of hepatocytes by nonviral causes usually restored by liver regeneration and infection of cholangiocyte precursor cells might impair liver regeneration in COVID-19, leading to further deterioration of liver function.

In summary, the preliminary studies suggest that the strong predilection for cholangiocyte infection and consequently impaired liver regeneration might be responsible for liver injury in COVID-19.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Funding

None.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Pramod Kumar: Conceptualization, Writing - original draft. Mithun Sharma: Writing - review & editing. Anand Kulkarni: Writing - review & editing. Padaki N. Rao: Supervision.

References

- 1.Agarwal A., Chen A., Ravindran N., To C., Thuluvath P.J. Gastrointestinal and liver manifestations of COVID-19. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2020;10:263–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F.S. Liver injury in COVID-19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428–430. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chai X., Hu L., Zhang Y. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-ncov infection. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.02.03.931766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seow J.J.W., Pai R., Mishra A. scRNA-seq reveals ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression in TROP2+ Liver Progenitor Cells: Implications in COVID-19 associated Liver Dysfunction. bioRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan G.W., Gao L., Wang J.W. Exploring the mechanism of liver enzyme abnormalities in patients with novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2020 doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2020.02.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okabe M., Tsukahara, Tanaka M. Potential hepatic stem cells reside in EpCAM+ cells of normal and injured mouse liver. Development. 2009;136:1951–1960. doi: 10.1242/dev.031369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao B., Ni C., Gao R. Recapitulation of SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cholangiocyte Damage with Human Liver Organoids. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00718-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]