Abstract

A facile, environment-friendly, versatile and reproducible approach to the successful oxidation of fullerenes (oxC60) and the formation of highly hydrophilic fullerene derivatives is introduced. This synthesis relies on the widely known Staudenmaier’s method for the oxidation of graphite, to produce both epoxy and hydroxy groups on the surface of fullerenes (C60) and thereby improve the solubility of the fullerene in polar solvents (e.g. water). The presence of epoxy groups allows for further functionalization via nucleophilic substitution reactions to generate new fullerene derivatives, which can potentially lead to a wealth of applications in the areas of medicine, biology, and composite materials. In order to justify the potential of oxidized C60 derivatives for bio-applications, we investigated their cytotoxicity in vitro as well as their utilization as support in biocatalysis applications, taking the immobilization of laccase for the decolorization of synthetic industrial dyes as a trial case.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Carbon nanotubes and fullerenes

Introduction

The discovery1 of fullerene (C60) in 1985 and the establishment of a protocol for its bulk production2 has had a widespread impact throughout science due to C60’s special physico-chemical and optical properties, as well as the specific chemical reactivity resulting from the unique cage structure3. Fullerene research has produced breakthrough highlights in the fields of superconductivity, organic ferromagnets, photovoltaics, thin-film transistors, and catalysis4–13. Nonetheless, the exploitation of this extraordinary molecule for applications in disciplines such as biochemistry, biology and medicine is hampered by its insolubility in a large number of solvents including especially water, where aggregation of the C60 molecules into micelle-like clusters is observed14. This problem has been addressed with the help of functionalization chemistry15,16, leading to water-soluble fullerene hybrids17,18 and to the synthesis of numerous fullerenes derivatives19,20 targeted to meet specific needs in materials science21, biomedical chemistry18,22–24, and pharmaceutical research25.

Over the last decades covalent functionalization of fullerenes has been extended to include various functionalization reactions3,19,25–27, among which the most commonly employed is the Prato reaction for fullerene functionalization through fulleropyrrolidine formation based on the 1,3 dipolar cycloaddition28–30. As a result, a plethora of organic reagents rich in biological and pharmaceutical activity have been covalently attached to C60, yielding derivatives with enhanced properties for a broad range of biological and medicinal applications18,23,31–36. All these reactions imply complicated manipulation and require special experience in handling. There is therefore a growing demand for controllable and easy-to-handle methods for the functionalization of C60.

Here we report a novel, easy, versatile, and reproducible procedure for the chemical oxidation of C60, on the basis of Staudenmaier’s method37, which is a controllable synthesis, extensively studied for the oxidation of graphite into graphene oxide38. We wish to emphasize that we used a variant of Staudenmaier’s method here because fullerenes are more sensitive than other carbon forms (CNTs, Graphene) and hence direct application of Staudenmaier’s method may lead to insufficient and not well-defined structures and functional groups. We show that through a variant of this method, the properties of pristine fullerenes can be tailored, introducing a combination of oxygenated functional groups, which in turn constitute reacting sites for chemical derivatization. In comparison with the other oxidation methods39–49 our proposed procedure exhibits a higher yield of oxygen functional groups and therefore greatly enhances the fullerene’s hydrophilicity, while the epoxy groups provide the ability to interact covalently with amines at ambient conditions. Contrary to other protocols reported in the literature, this synthesis method does not require high temperatures50 nor does it lead to the creation of clusters, aggregation or by-products51, all phenomena hindering hydrophilicity52. Our approach is suitable for up-scaling to mass production because, differently from other methods reported, because it presents no inherent synthetic difficulties and/or yield limitations51,53,54. In more detail, as a consequence of the strong acid treatment, the surface of the fullerene molecule is decorated with diverse oxygen functionalities, converting the completely insoluble fullerene into a hydrophilic molecule soluble in many polar solvents, while maintaining its stereochemistry (spherical shape). To substantiate this claim, we have investigated the evaluation of the in vitro cytotoxic activity of the C60 hybrids, performed against mouse leiomyosarcoma (LMS) and human lung cancer (A549), as well as a normal cell line, normal human fetal lung fibroblasts (MRC-5).

An additional huge benefit derived from the creation of epoxy moieties is the possibility of further functionalization with numerous organic species via covalent bonding to the epoxy groups, a method that has been extensively employed for the chemical functionalization of graphite oxide55–57. Further functionalization of oxidized C60 with a primary aliphatic amine was performed to confirm the presence of epoxy moieties and to attest this oxidative method as a controllable and reproducible step for the creation of new C60 derivatives. X-ray photoelectron (XPS), Raman and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopies, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), in conjunction with powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed for the material’s characterization.

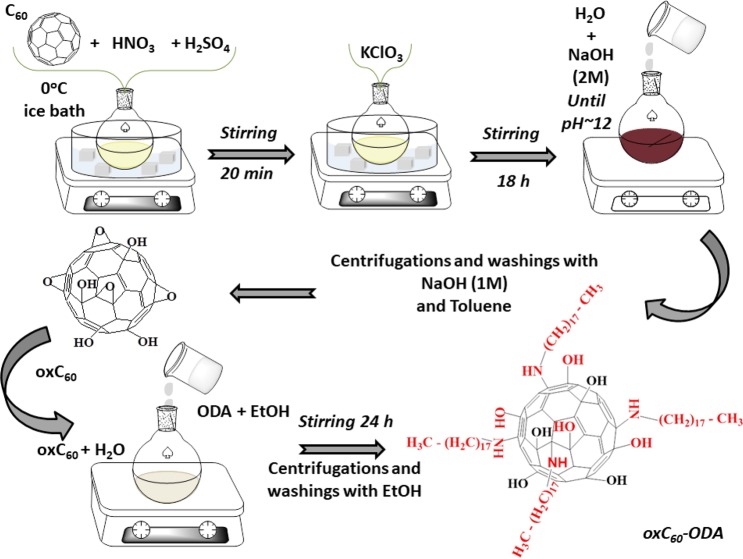

The following figure (Fig. 1) illustrates the synthetic method for the production of oxidized C60 and its derivatives.

Figure 1.

Synthetic method for the production of oxidized C60 and its derivatives.

Laccases (benzenediol: oxygen oxidoreductase; E.C. 1.10.3.2) belong to multi-copper containing oxidases and their activity is based on the reduction of molecular oxygen to water with the simultaneous one-electron oxidation of aromatic substrates58. In addition, laccases, due to their ability to oxidize different substrates, are potential candidates for many biotechnological and industrial applications, such as decolorization of synthetic dyes59. Herein, the immobilization of a native laccase from White rot fungi on the newly synthesized oxC60-ODA was performed and further used for the decolorization of two synthetic dyes with industrial applications.

Material and methods

Production of oxidized fullerene (oxC60)

oxC60 was obtained by a modified Staudenmaier’s method. In a conical flask, 100 mg of C60 (98%, Sigma-Aldrich) were added upon stirring to a mixture of 4 mL of H2SO4 (95–97%) and 2 mL of HNO3 (65%) kept in an ice-water bath at 0 °C. 700 mg of KClO3 were then added in little portions to the solution under vigorous stirring and the reaction was continued for 18 hours. 20 mL water were then added and the mixture was stirred for another 30 minutes. The resulting aqueous acid mixture was neutralized by slowly adding a 2 M NaOH solution until a pH of 12 was reached. The precipitate was separated from the solution by centrifugation, washed with a 1 M NaOH solution and centrifuged again60. The product was washed three times in order to eliminate the remaining salts used or formed during the oxidation procedure. The precipitate was dispersed in 50 mL of toluene, stirred for 20 min and centrifuged to remove unreacted fullerenes. Finally, the oxidation product was dispersed in ethanol and air-dried on a glass plate. The final material possessed a yield of approximately 50% (based on the weighted mass).

Characterization tools

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra over the spectra range 400–4000 cm−1 were recorded with a Perkin–Elmer Spectrum GX infrared spectrometer featuring a deuterated triglycine sulphate (DTGS) detector. Every spectrum was the average of 64 scans taken with 2 cm−1 resolution. Samples were prepared as KBr pellets with ca. 2 wt% of sample. Raman spectra were collected with a Micro – Raman system RM 1000 RENISHAW, using a laser excitation line at 532 nm (Nd – YAG), in the range of 1000–2400 cm−1. A power of 1 mW was utilized with a 1 μm focusing spot so to avoid photodecomposition of the samples. 13C NMR spectrum of oxC60 was recorded in D2O using a Bruker Avance DRX spectrometer operating at 125.1 MHz. Thermogravimetric measurements were carried out with a Perkin Elmer Pyris Diamond TG/DTA. Samples of about 5 mg were heated in air from 25 °C to 900 °C, at a rate of 5 °C min−1. Differential scanning calorimetry was applied using a Q100 Thermal Analysis instrument between 25 °C and 200 °C under inert atmosphere (nitrogen), at heating and cooling rates of 2 °C min−1. DSC measurements were done placing the sample in an open vessel to reproduce the conditions of TGA. High-resolution X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected with a monochromatic Cu Kα (λ = 1.5418 Å) radiation source (operated at 30 keV and 35 mA) and a vertically mounted INEL cylindrical position-sensitive detector (CPS120), used in the Debye-Scherrer geometry to enable simultaneous acquisition of the diffraction profile over a 2θ range between 4° and 120° (with an angular step of 0.029° (2θ)). For the XRD measurements, the powder was placed into a Lindemann capillary tube (0.5 mm diameter). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed under ultra-high vacuum (2 ×10−9 mbr) and data were collected using an SSX-100 (Surface Science Instruments) instrument equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (hν = 1486.6 eV). The energy resolution was set to 1.2 eV in order to minimize data acquisition time and maximize the signal-to-noise ratio and the photoelectron take off angle was 37° with respect to the surface normal in order to minimize data acquisition time and maximize the signal-to-noise ratio. All binding energies were referenced to the C1s core level photoemission line at 285.0 eV61. Spectral analysis included a Shirley background subtraction and peak deconvolution with Gaussian-Lorentzian functions in a least-squares curve-fitting program (Winspec) developed at the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire de Spectroscopie Electronique, Universitaires Notre-Dame de la Paix, Namur, Belgium. For the N1s line, we applied a linear background subtraction because the low peak intensity did not allow for Shirley background subtraction. The photoemission peak areas of each element used to calculate the amount of each species within the probed volume were normalized to the sensitivity factors of each element specific to the spectrometer. All the measurements were made on freshly prepared samples in order to assure the reproducibility of the data. Three different spots were measured on each sample to check for reproducibility.

Evaluation of the in vitro cytotoxic activity of oxC60 - Cell lines

To consistently evaluate the cytotoxicity of water-soluble oxC60 we used two cancer cell lines, mouse leiomyosarcoma (LMS) and human lung cancer (A549) as well as a normal cell line, normal human fetal lung fibroblasts (MRC-5). The latter was kindly provided by Dr. Evangelos Kolettas, Laboratory of Biology, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ioannina, Greece. All different cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/mL penicillin, 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin and 1.4 mM L-Gloutamin, at 37 °C, with 5% CO2. MTT assay: The ability of the oxidized fullerenes to inhibit the cell growth was expressed by the average IC50 value (oxC60 concentration required for 50% inhibition of cell growth) and was analyzed using the MTT assay (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide)62. Briefly, 3 × 103 for both LMS and A549 cells, as well as 5 × 103 MRC-5 cells, were cultured overnight on 96-well plates and culture media containing different concentrations (ranging from 200 to 2000 μg mL−1) of oxC60 were added. The oxC60 was dissolved in sterilized water (solvent). The 96-well plates with culture media containing different volumes of solvent, equal to volumes of solutions added to the test wells, were considered as control. After incubation for 48 h, 50 μL of MTT were added in each well from a stock solution (3 μg mL−1), and incubated for additional 3 h. The yielded purple formazans were re-suspended in 200 μL of DMSO, using a multi-channel pipette. The solution was spectrophotometrically measured (540 nm, subtract background absorbance measured at 690 nm) using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiskan Spectrum, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). All the experiments were performed at least in triplicate. IC50 values were determined by the curve of percentage of inhibition versus dose.

Further chemical functionalization of oxC60 with octadecylamine

100 mg of oxidized fullerenes, dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water, were mixed with a solution of 300 mg of octadecylamine (ODA) in 16.5 mL of EtOH while the pH was set to 7 and the system was stirred for 24 h. The product was collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and dried at room temperature (sample denoted as oxC60-ODA). The synthesized material presented a yield of approximately of 45% (based on the weighted mass).

Non covalent immobilization of laccase

Laccase from White rot fungi (10,000 U/mL, WrfL) was purchased from Creative Enzymes (New York, USA). Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI), N-hydrosuccinimidyl ester (NHS), Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (CBB), Bromophenol Blue (BpB), 1-Hydroxybenzotriazole (HBT) and (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES) were purchased from Sigma. In our standard protocol, 3 mg of oxC60-ODA in 5 mL of acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.58) were sonicated for 30 min. Then 1 mL of WrfL was added and the mixture was incubated under stirring for 1 h at 30 °C. The nanomaterial-enzyme conjugates were separated by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm and then were washed three times with buffer solution to remove loosely bound protein. The immobilized WrfL was dried over silica gel and was stored at 4 °C until used.

Covalent immobilization of laccase via diimide-activated amidation

3 mg of oxC60-ODA in 6 mL of distilled water were sonicated for 30 min. Then 1.2 mL of a 10 mg mL−1 CDI aqueous solution was added to the above suspension. Under fast stirring, 2.3 mL of a 50 mg mL−1 NHS aqueous solution were added quickly and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. The activated nanomaterials were separated by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm and washed three times with HEPES buffer (50 mM, pH 4.58) to remove the excess of CDI. The activated nanomaterials were re-dispersed in 5 mL of HEPES buffer solution. Then, 1 mL of WrfL was added and the mixture was treated as described for non-covalent procedure.

Dye decolorization

To study the decolorization ability of the immobilized enzymes, 0.1 mg mL−1 of immobilized laccase and 1 mM HBT was added to each dye solution (70 μM of CBB and BpB) followed by incubation in a rotary shaker (30 °C and 120 rpm). The solution was sonicated for 3 minutes to achieve full and stable dispersion of the nanomaterial-enzyme conjugates. Samples were taken from each reaction mixture and the decrease in the absorbance at 545 nm was recorded in specific time intervals. The percentage of dye decolorization was calculated as the formula:

where, Ai: initial absorbance of the dye, At: absorbance of the dye at any time interval. Negative controls (reaction mixtures without enzyme) were designed as a reference to compare decolorization percent of treated samples. Each decolorization experiment was performed in triplicate and mean of decolorization percentage was reported.

Results and Discussion

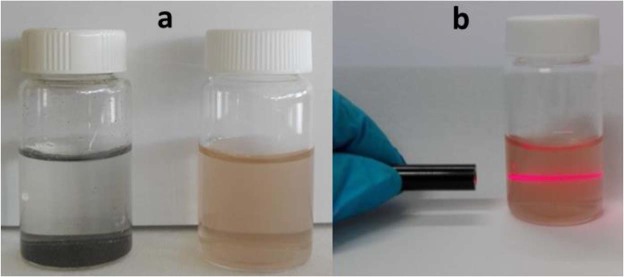

The first indication of successful oxidation came from the solubility behavior of the products estimated at 13 mg/mL (Fig. 2a), a high value compared to other synthetic procedures60: The enhanced solubility in water and other polar solvents (like DMSO, 1 mg/mL) can be explained only if a hydrophilic sheath of oxygen-containing groups attached to and surrounding the surface of the fullerene cage is present. Such a high dispersibility in water is expected for polar oxygen-containing groups, distributed more or less homogeneously around the spheroid thus preventing aggregation63. Tyndall scattering, observed when the beam of a laser pointer is directed onto an aqueous colloidal dispersion of oxC60, provides additional proof for the successful oxidation of fullerenes (as shown in Fig. 2b). This phenomenon is a clear evidence of an excellent dispersibility of C60 molecules in aqueous media.

Figure 2.

(a) Completely insoluble C60 molecules in water (left) and water soluble oxidized fullerene (right), (b) Tyndall scattering observed when a laser pointer is directed onto an aqueous colloidal dispersion of oxC60.

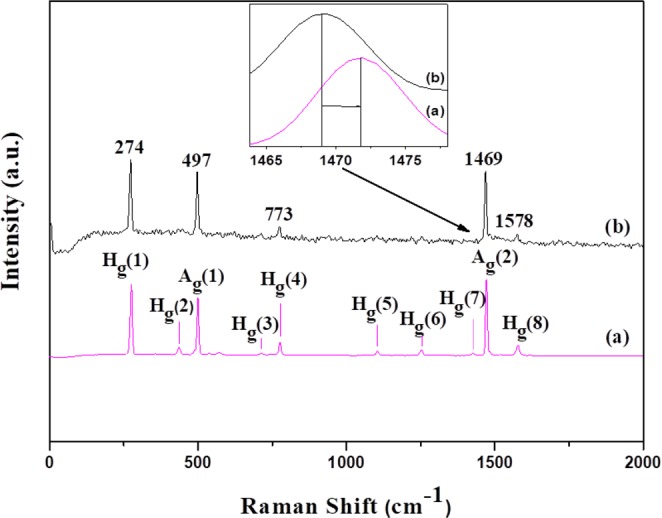

Vibrational spectroscopy was employed to identify chemical and structural changes as well as to verify the molecular integrity of the C60 cage before and after the chemical modification. Figure 3 displays the Raman spectra of C60 and of oxC60 powder samples. In pristine C60 10 of the 46 vibration modes are Raman active (2Ag + 8Hg) and four (4F1u) are infrared active2,64,65. The most prominent bands centered at 499 cm−1 and 1471 cm−1 (Fig. 3a) are assigned to the symmetrical radial breathing motion of the sixty carbon atoms (Ag(1)) and to the tangential stretching mode of five-fold pentagon carbons (pentagonal pinch mode Ag(2)), respectively2,64,65. The rest of the bands are attributed to the eight Hg Raman active modes, distributed between 273 cm−1 and 1578 cm−1 as indicated in Fig. 3a. After oxidation, the number of active Raman modes decreases with respect to pristine fullerite (Fig. 3b). Only the most intense bands are visible after oxidation, and exhibit a small shift of approximately 2 cm−1 with respect to those of C60. These changes can be attributed to hindrance of the free rotation motion due to the creation of oxygen-containing functional groups: while the C60 molecules in pristine fullerite behave as free rotors at room temperature, the addition of hydroxyl and epoxy/carbonyl groups on the surface of the cage likely leads to the reduction of this rotational movement at ambient temperature possibly due to steric effects or inter-molecular bonding66. Importantly, the 1469 cm−1 band persists after the oxidation process. This vibration is due to the symmetric Ag vibration mode of the spherical framework of the C60 cage, thus confirming that the icosahedral structure is intact67,68.

Figure 3.

Raman spectra of (a) pristine C60 and (b) oxidized fullerene (oxC60).

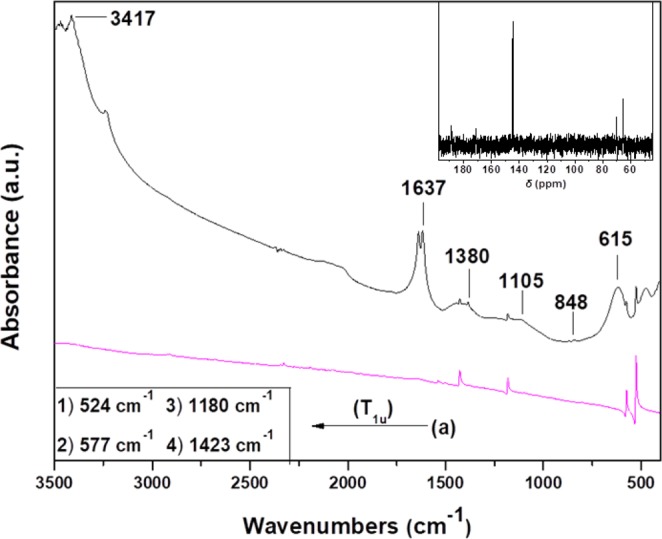

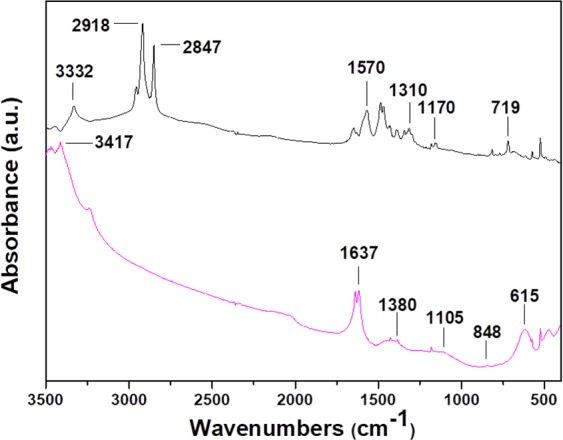

The FTIR spectra of C60 and oxC60 are presented in Fig. 4. The four IR active vibration modes with F1u symmetry of pristine fullerite (a) are located at wavenumbers of 524, 577, 1180, and 1423 cm−1 and assigned to radial displacements of the carbon atoms for the two lowest wavenumber bands and to tangential modes of carbon atoms for the two modes above 1000 cm−1 69. The infrared spectrum of the oxidized fullerene (b) reveals the existence of additional peaks compared to C60, namely bands at 615 cm−1 and 848 cm−1, which are assigned to wagging vibrations of hydroxyl groups and in the wavenumber range between 1050 cm−1–1470 cm−1 three new bands, one centered at 1105 cm−1, which is attributed to stretching vibrations of C-O-C ether (epoxide) species70, and two located at 1380 cm−1 and 1442 cm−1 stemming from stretching vibrations of C-OH groups71. Finally, the intense band at 1637 cm−1 might be due to water bending, which would be in agreement with the increased hydrophilic character of the oxidized fullerene derivatives.

Figure 4.

FT-IR spectra of (a) pristine (C60) and (b) oxidized fullerene (oxC60). Inset: 13C NMR spectrum of oxC60 was recorded in D2O.

The successful oxidation of C60 was also assessed by 13C NMR spectroscopy. Specifically, in the 13C NMR spectrum of oxC60 (Fig. 4 inset, right top), a peak at 144 ppm attributed to the carbon atoms of the cage is shown. Additionally, the peaks at 186 and 171 ppm are assigned to carbon atoms of carbonyl and carboxyl groups, respectively, while the peaks at 71 and 67 ppm are attributed to carbon atoms of epoxy and tertiary alcoholic moieties. Therefore, these findings, which are in line with the FTIR results and the literature72, suggest the successful decoration of oxC60 with oxygen containing groups, which are mainly epoxy and hydroxyl groups, but also carbonyl and carboxyl moieties are present.

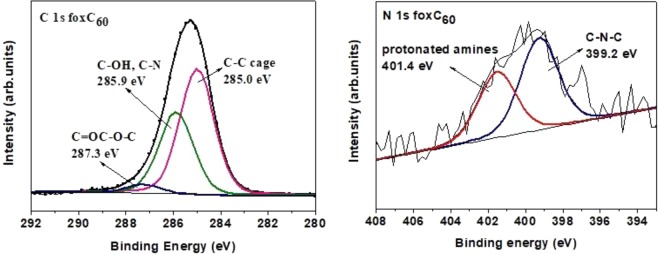

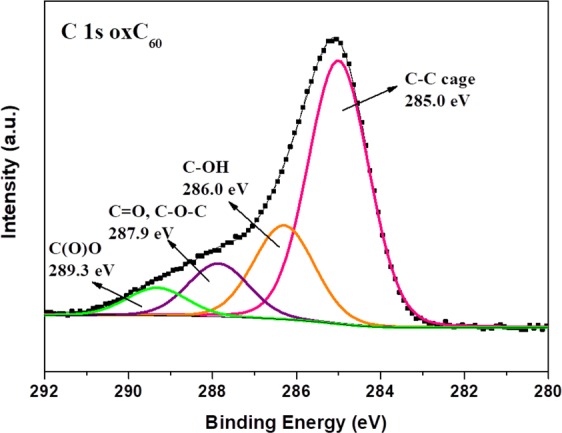

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was applied to attest the presence of oxygen-containing functional groups covalently attached on oxC60. XPS is a widely used technique for the chemical characterization of fullerene derivatives since it is not only sensitive to all chemical elements (except H), but also to the local environment surrounding the atoms of that element in a given compound. The C1s core level region of the XPS spectrum of oxC60, presented in Fig. 5, displays four components at 285.0, 286.0, 287.9 and 289.3 eV. The most intense one at 285.0 eV arises from the carbon-carbon aromatic bonds, and accounts for 60.1% of the total carbon intensity, while rest of the spectral intensity stems from carbon atoms that are involved in heterogeneous bonds. A percentage close to 60% may be expected since the maximum amount of side groups that can be covalently attach to single carbon atoms of the C60 cage without any two being adjacent, is 24; this is also the highest number stated for methylization, chlorination or bromination of fullerene3 entailing that 36 of the 60 atoms of the carbon cage (i.e., exactly 60%) are not bonded to any functional group. The component centered at 286.0 eV is due to carbon atoms forming C-OH bonds and represents 21.6% of the total C1s intensity. The contribution at 287.9 eV is assigned to C=O double bonds and/or C-O-C epoxy moieties, and accounts for 12.1% of the total carbon signal. The spectral profile reveals a contribution located at 289.3 eV which represents 6.2% of the total carbon amount. This weak contribution can be accounted for by considering that the strong oxidation treatment probably leads to the creation of a small amount of carboxyl groups. If this small percentage is discarded for the quantitative analysis, then our XPS results indicate that the average oxC60 molecule has 22 of the 60 carbon atoms involved in heterogeneous bonds and consists of a C60 cage surrounded by 14 hydroxyl groups and by either 4 epoxy moieties or 4 – m epoxy moieties and 2 m carbonyl oxygens with m between 1 and 4 (the number of carbon atoms forming an epoxy moiety is twice the number of epoxy oxygens as each oxygen is linked to two carbons). This yields the average chemical formula for oxC60 as C60(OH)14On with n between 4 and 8. Taking into account also the ratio between the intensities of the C1s and O1s photoemission lines (normalized with the respective sensitivity factors), these results confirm the successful oxidation of C60 by the creation of functional oxygen groups with a ratio of carbon to oxygen (C/O) equal to 2.260.

Figure 5.

X-ray photoemission spectrum of the C1s core-level region of oxidized fullerene (oxC60).

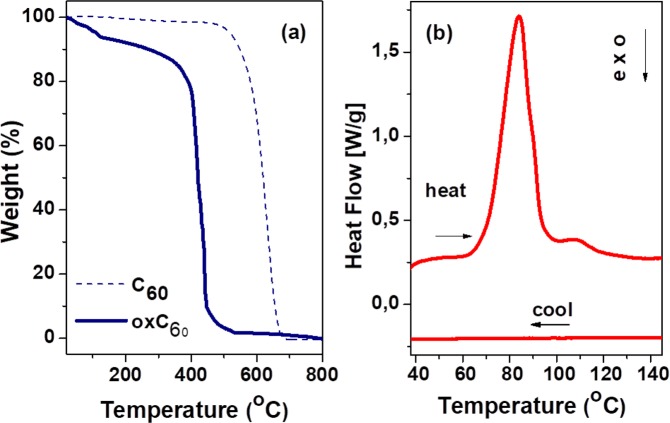

Further evidence for successful oxidation of C60 is provided by thermal decomposition experiments: the required temperature for desorption of functional groups bound to C60 is significantly lower than the decomposition temperature of the pure fullerene, enabling also selective removal of the oxygen functional groups in a thermal scan (see below). Figure 6(a)presents the TGA plots of the oxC60 sample and of the initial C60 material measured with a heating rate of 5 °C/min in air. As evident from the TGA curve of the pristine C60 sample, the combustion of fullerite takes place at temperatures between 500 and 700 °C. In the case of oxidized fullerenes, the sample is found to combust at lower temperatures. In fact, the weight loss already starts before 100 °C (due to loss of the epoxy and carbonyl side groups, see below) and progressively continues until a total weight loss is reached when heating the sample up to 700 °C. The main drop in the mass, corresponding to decomposition (combustion) of the oxidized fullerene cages, occurs between 350 and 470 °C, i.e. at considerably lower temperature than the decomposition temperature of pure fullerene73 due to the presence of hydroxyl groups, as detailed in the following.

Figure 6.

(a) TGA curves of pristine and oxidized fullerene. (b) DSC thermogram of oxidized fullerene between 40 and 145 °C (heating-cooling cycle).

Figure 6(b) displays the scanning calorimetry data acquired on as-synthesized oxC60 during a heating-cooling cycle between 40 and 145 °C. Upon heating, the oxC60 powder displays an irreversible double endothermic transition with onset at 65 °C, a more intense peak just above 80 °C and a minor one above 100 °C. A very similar line shape is obtained by differentiating the TGA data (not shown). As visible in Fig. 6(a), such a double endothermic transition is accompanied by a mass loss of approximately 6.5%, a value consistent with the loss of only the oxygen groups (epoxy and carbonyl) according to the chemical formula C60(OH)14On with n between 4 and 5.

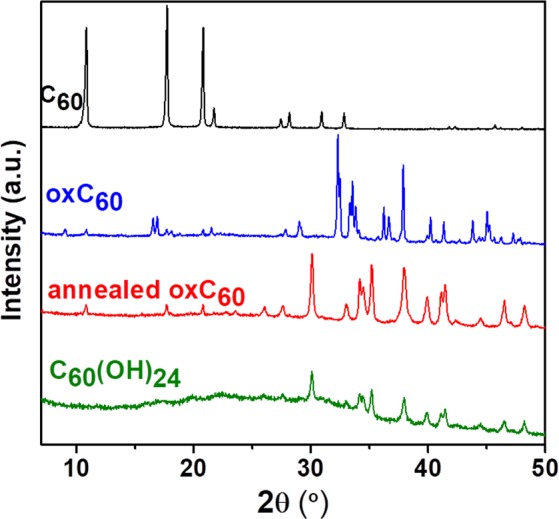

The confirmation that the endothermal mass loss is due to selective breaking of the oxygen side groups is provided by the analysis of the powder X-ray diffraction results. The room-temperature diffraction pattern of as synthesized oxC60 (Fig. 7) indicates that the sample is polycrystalline. The diffraction profile is quite different from that of pristine fullerite (also shown in the same figure for comparison), which confirms the successful functionalization of C60 via oxidation74. Only traces amount of unreacted C60 are present, detectable by the presence of minor diffraction peaks in correspondence to the three main Bragg peaks of pristine fullerite. The pattern of oxC60 exhibits the first diffraction peak around 9° in 2θ scale, i.e., at a significantly lower angle than the first peak of pristine C60 (approximately 11°), indicating that the lattice spacing is larger in oxC60 than in fullerite due to the presence of the side groups, which act as steric barriers against denser packing. Upon annealing at temperatures higher than 75 °C, the diffraction pattern of the oxidized fullerene powder changes abruptly, with the appearance of new peaks and the disappearance of all the peaks characteristic of the structure of as-synthesized oxC60 (at the same time, the pristine C60 peaks become more visible). The resulting spectrum (labeled as “annealed oxC60” in Fig. 7) is strongly reminiscent of that of polyhydroxylated fullerenes (fullerol C60(OH)24) or that of the related derivative C60(ONa)2475, both of which were synthesized following a completely different route than that used here to produce oxC6053,76. The fact that the diffraction peaks of the oxC60 sample warmed to 80 °C or above match those of fullerol indicates that annealing causes selective disruption of the oxygen adducts (epoxy and carbonyl), leading, as a result of the partial decomposition, to the formation of polyhydroxylated fullerenes. An only partial decomposition may be expected since the oxygen adducts are more reactive and therefore more labile than the hydroxyl groups, which in fullerol are lost only above 150 °C53. The partial decomposition and the survival of hydroxyl groups also rationalize why the final combustion of the sample occurs at much lower temperatures than for pristine C60 (Fig. 6(a)). The observation of a diffraction pattern identical to that of the high-symmetry C60(OX)24 molecules (X = H, Na) is a direct confirmation that the quasi-spherical shape of pristine fullerene is retained after oxidation to oxC60. The synthesized product is therefore characterized by a symmetric distribution of functional moieties around the carbon skeleton63.

Figure 7.

Room-temperature X-ray powder diffraction pattern of oxidized fullerene (oxC60), both prior to and after annealing at 100 °C. For comparison, also the XRD patterns of pristine fullerite (C60) and of fullerol [C60(OH)24] are shown (own data).

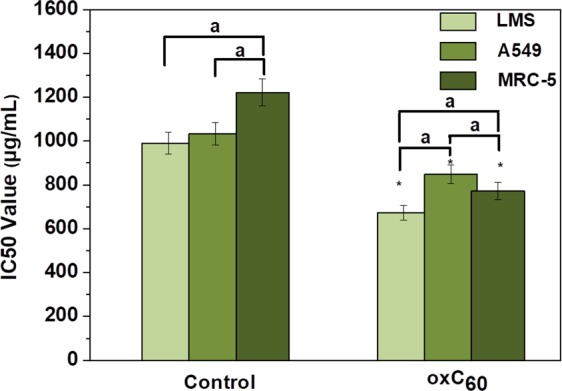

Very few studies have evaluated the cytotoxic activities of fullerenes. In the present study we evaluated the in vitro cytotoxic activity of oxC60 against LMS and A549 (cancer cell lines) and MRC-5 (normal cell line). Figure 8 represents the IC50 values of the oxidized fullerenes (oxC60) in all above mentioned cell lines. It was shown that the oxC60 presented high toxicity in all cell lines compared to the control (solvent) (p < 0.05). Also, within the treatment group oxC60 showed higher toxicity in LMS cells with an IC50 of 670 ± 42 μg/mL. Significant lower toxicity was shown in the other two cell lines with the IC50 values to be 850 ± 20 μg/mL and 775 ± 41 μg/mL for A549 and MRC-5, respectively (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

IC50 values in μg/mL of oxC60 on LMS, A549 and MRC-5 cells. *p < 0.05, statistical significant difference compared to the control (solvent); ap < 0.05, statistical significant difference between the cell lines within the treatment group.

It has been shown previously that C60 is able to inhibit the cell growth mainly due to its antioxidative properties77 and partly through other mechanisms78,79. Also, fullerenes cause cytotoxicity in various cancer cell lines through the molecular events of oxidative stress80–82 or lipid peroxidation83,84 Here, we have shown that oxC60 caused significant cytotoxicity in cancer and normal cell lines. Although the exact mechanism of action is not known, we speculate that oxC60 acts in the same way as fullerenes, and possibly through the oxidative stress mechanism.

To confirm the presence of epoxy moieties on the oxC60 cage and thus the possibility to further functionalize the oxidized fullerene, an additional experiment was performed in which a primary aliphatic amine (octadecylamine, ODA) was successfully attached through covalent bonding onto the surface of the oxC60 molecule. Chemical grafting of the amine end groups via SN2 nucleophilic substitution reactions can only take place on the epoxy groups present in the oxidized fullerene. The organophilic character of the produced fullerene derivative resulted in an enhanced solubility in organic solvents including hexane (0.4 mg/mL), toluene (1.5 mg/mL), and chloroform (1.5 mg/mL), which provides the primary evidence for the covalent functionalization of oxC60 with ODA.

XPS and FTIR were employed to verify the covalent bonding of ODA on the surface of oxC60. After functionalization with ODA, XPS measurements revealed the presence of new components stemming from the formation of covalent carbon-nitrogen bonds at the epoxy sites. More specifically, the analysis of the C1s XPS spectrum of oxC60–ODA (Fig. 9 left) allows singling out the characteristic component due to carbons involved in the fullerene cage as well the C-C chain of the –ODA at 285.0 eV contributing with 58.2% to the total C1s intensity. The relative spectral weight of the feature at 285.9 eV is significantly larger than in the oxC60 case (Fig. 5), changing from 21.6% before to 37.9% after the functionalization. This change is due to the creation of covalent C-N bonds linking the organic chains to the carbon cage structure, as the binding energies values for carbon atoms linked to amine or hydroxyl groups are very similar62. Lastly, a weak component centered at 287.3 eV and representing 3.9% of the total C1s intensity is attributed to carbonyl moieties, since the contribution of the epoxy oxygens is absent due to the creation of the C-N-C bridges of the organo-modified fullerene derivative. Very intriguing and a clear evidence for the integrity of fullerene molecules, is the total absence of the spectral signature of carboxyl groups in the C1s spectrum of oxC60-ODA (Fig. 9, left panel), unlike for the oxidized fullerene (Fig. 5). Thus the carboxyl groups, which were created (during the acid treatment) due to the breakage of a very small amount of fullerene cages, are absent after organic functionalization. This implies that these formations did not take part in the reaction as soon as carboxylic groups can react with amines under specific conditions and not in ambient conditions by which the experiment took place. A possible explanation for this is that the tiny amount of fullerenes possessing carboxylic moieties keep their hydrophilic character, and are thus removed from the reaction products upon washing with ethanol and water during the synthetic procedure. This provides a means to purify the oxC60-ODA derivative.

Figure 9.

X-ray photoemission spectrum of the C1s (left) and N1s (right) core level regions of functionalized oxidized fullerene (oxC60–ODA).

Additional information on the type of interaction of ODA with the oxidized fullerenes comes from the N1s core level region of the photoelectron spectrum (Fig. 9, right-hand panel). The N1s line can be modeled with two main components centered at 399.2 eV and 401.3 eV binding energy, which correspond to the creation of the epoxy amine bond (C-N-C)85–87 and to protonated amines of the ODA moieties, respectively88. This entails that some of the ODA moieties are not covalently bonded to the fullerene cage, but are instead weakly bound to the sample (possibly via the formation of hydrogen bonds with the oxygen-containing groups of oxC60). The carbon to nitrogen ratio is estimated at 20.2 showing that each oxidized fullerene molecule is surrounded by several (more than a dozen) ODA moieties. The carboxylated carbon formations, which are created (during the acid treatment) due to the breakage of a very small amount of fullerene cages is absent after the organic functionalization. For this reason by the organic functionalization of ox-C60 we can impart new properties to the hydrophilic fullerenes, which is very important for specific applications as well clear the rest of the carbon impurities, which are created from the strong oxidation and destroy the ball-shape of the C60.

The successful incorporation of ODA and the creation of a new fullerene derivative were further confirmed by FT-IR spectroscopy, as shown in Fig. 10. The spectrum of oxC60–ODA shows absorption bands, which are absent in the spectrum of pristine C60 (compare with Fig. 4). More specifically, for the functionalized fullerene we observe a band at 718 cm−1, which is attributed to the wagging vibration of N-H stemming from non-covalently bonded ODA. The absorption bands at 1570 cm−1 (in plane-deformation) and 3332 cm−1 (stretching) are similarly assigned to vibrations of NH2 groups, while C-N stretching vibrations are observed at 1170 cm−1 and 1310 cm−1. Moreover, the peak at 1105 cm−1 due to epoxide vibrations disappears upon functionalization, indicating that the primary amines of ODA have reacted with the epoxide groups of the oxC60. These results together confirm the initial presence of epoxy oxygens in oxC60. Finally, the bands at 2847 and 2918 cm−1 are attributed to symmetric and asymmetric vibrations of -CH2-and –CH3 (alkyl groups), respectively, indicative of the presence of aliphatic hydrocarbon chains of ODA moieties attached to the carbon cage89.

Figure 10.

FTIR spectrum of oxidized C60 (oxC60) (black line) and functionalized oxidized C60 (oxC60-ODA) (purple line).

Dye decolorization

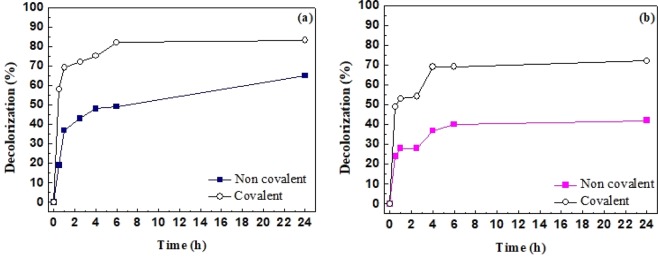

The synthesized nanomaterial oxC60-ODA was used as matrix for the covalent and non-covalent immobilization of laccase from White rot fungi (WrfL), and its further application for the decolorization of two synthetic dyes of industrial and biotechnological interest, Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 (CBB) and Bromophenol Blue (BpB). Laccases are known to be capable of catalyzing the oxidation of synthetic dyes and hold potential for applications in sensing and bioremediation of industrial effluents90,91. The mediator hydroxybenzotriazole (HBT) was used to facilitate the decolorization of the chosen dyes. HBT acts as a sort of an electron bridge between the enzyme and the substrate. Firstly, HBT is oxidized by laccase, diffuses away from the enzymatic pocket and in a next step oxidizes other molecules, extending, this way, the range of substrates that can be efficiently catalyzed by laccase, and thus increasing its catalytic activity92. The decolorization efficiency of the immobilized laccase against CBB and BpB is presented in Fig. 11. As seen, in all cases studied, both covalent and non-covalent immobilized laccase appeared to efficiently decolorize the chosen dyes to a high extent. More specific, covalently immobilized WrfL presents high efficiency, since the decolorization rate for CBB and BpB reached up to 60 and 50%, respectively, even after 0.5 h of incubation. The results indicate that this novel nanobiocalytic system shows great efficiency for dye degradation, even higher than other immobilized laccases reported previously93,94. The beneficial impact of different carbon-based nanostructures on the catalytic characteristics of enzymes has already been demonstrated92,95. The use of ODA for the functionalization of oxC60 and the targeted immobilization of WrfL increases the space between the nanomaterial and the protein, reducing in this way any undesired interactions between them95. Moreover, any substrate diffusion limitations are minimized, resulting in high catalytic activity for dye decolorization. The results indicate that oxC60-ODA can be excellent support for enzyme immobilization for use in applications of biotechnological and industrial interest.

Figure 11.

Decolorization of (a) CBB and (b) BpB by immobilized WrfL on oxC60-ODA (In all cases, the standard deviation was <3%).

Conclusions

A combination of characterization techniques was applied in order to illustrate the successful chemical oxidation of fullerene (C60) into a highly oxidized analogue (oxC60) by means of a variant of Staudenmaier’s method, an easy oxidation protocol up to now extensively used for the chemical oxidation of graphite. This oxidation leads to the formation of a highly soluble fullerene derivative (that could be called “fullerene oxide” similar to graphene oxide) through the creation of oxygen-containing functional polar groups on the surface of C60, while retaining its spherical structure and represents a very crucial step for the utilization of the entire fullerene family in applications such as medicinal chemistry and biochemistry, which require solubility in various polar solvents. Apart from its simplicity, the main advantage of this method compared to others applied so far for the production of soluble C60 derivatives, arises from the creation of epoxy groups on the surface of the fullerene. A novelty of our synthetic approach is that it produces hydrophilic C60 molecules decorated with epoxy moieties in high yield but at low cost. The presence of these groups allows for further functionalization and thus for the creation of new hydrophilic fullerene derivatives without the need of high temperatures and complicated synthetic reactions. In fact, the epoxy groups can be readily modified via ring-opening reactions under various conditions. As representative example, a primary aliphatic amine (octadecylamine) was successfully attached through covalent bonding. The proposed method represents a novel simple, versatile and reproducible approach for the controllable production of various well-defined and stable fullerene derivatives by exploiting the well-established carbon chemistry.

Acknowledgements

This work has been partially supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through project FIS2014-54734-P and by the Generalitat de Catalunya under project 2014 SGR-581. P.Z. and K.S. acknowledge the Ubbo Emmius Program for PhD fellowships. M.P. is very thankful to the IKY Foundation for the post-doc financial support (MIS 5001552).

Author contributions

P.Z., D.G., P.R. conceived the presented idea. P.Z., K.S., D.G. and P.R. wrote the manuscript with support from E.M., M.B., R.M., M.P., H.S., I.V., A.V. and A.E. The experiments for the synthesis of oxidized fullerenes and fullerene derivatives carried out by P.Z. The characterizations of the final nanomaterials performed from P.Z., K.S., E.M., M.B., Z.S. and R.M. The study of the cytotoxicity in vitro of oxidized fullerenes was performed by IV, A.V. and A.E. M.P. and H.S. accomplished the experiments for the biocatalysis applications.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Panagiota Zygouri, Email: pzygouri@gmail.com.

Dimitrios Gournis, Email: dgourni@uoi.gr.

Petra Rudolf, Email: p.rudolf@rug.nl.

References

- 1.Kroto HW, Heath JR, Obrien SC, Curl RF, Smalley RE. C60 Buckminsterfullerene. Nature. 1985;318:162–163. doi: 10.1038/318162a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kratschmer W, Lamb LD, Fostiropoulos K, Huffman DR. Solid C60 - A new form of carbon. Nature. 1990;347:354–358. doi: 10.1038/347354a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor R, Walton DRM. The Chemistry Of Fullerenes. Nature. 1993;363:685–693. doi: 10.1038/363685a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holczer K, et al. Alkali-fulleride superconductors - synthesis, composition, and diamagnetic shielding. Science. 1991;252:1154–1157. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5009.1154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haddon RC. Electronic-structure, conductivity, and superconductivity of alkali-metal doped C60. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1992;25:127–133. doi: 10.1021/ar00015a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosseinsky MJ. Fullerene intercalation chemistry. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 1995;5:1497–1513. doi: 10.1039/jm9950501497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allemand PM, et al. Organic molecular soft ferromagnetism in a fullerene C60. Science. 1991;253:301–303. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5017.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bendikov M, Wudl F, Perepichka DF. Tetrathiafulvalenes, oligoacenenes, and their buckminsterfullerene derivatives: The brick and mortar of organic electronics. Chemical Reviews. 2004;104:4891–4945. doi: 10.1021/cr030666m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imahori H, Fukuzumi S. Porphyrin- and fullerene-based molecular photovoltaic devices. Advanced Functional Materials. 2004;14:525–536. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200305172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haddon RC, et al. C60 Thin-film transistors. Applied Physics Letters. 1995;67:121–123. doi: 10.1063/1.115503. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anthopoulos, T. D. et al. High performance n-channel organic field-effect transistors and ring oscillators based on C60 fullerene films. Applied Physics Letters8910.1063/1.2387892 (2006).

- 12.Gan, L. B. et al. Fullerenes as a tert-butylperoxy radical trap, metal catalyzed reaction of tert-butyl hydroperoxide with fullerenes, and formation of the first fullerene mixed peroxides C60(O)((OOBu)-Bu-t)(4) and C70((OOBu)-Bu-t)(10). Journal of the American Chemical Society124, 13384–13385, 10.1021/ja027714p (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Bosi S, Da Ros T, Spalluto G, Prato M. Fullerene derivatives: an attractive tool for biological applications. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2003;38:913–923. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortner JD, et al. C60 in water: Nanocrystal formation and microbial response. Environmental Science & Technology. 2005;39:4307–4316. doi: 10.1021/es0498099n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch, A. Functionalization of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Angewandte Chemie-International Edition41, 1853–1859, doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20020603)41:11<1853::aid-anie1853>3.0.co;2-n (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Georgakilas V, et al. Organic functionalization of carbon nanotubes. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:760–761. doi: 10.1021/ja016954m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson LJ, et al. Metallofullerene drug design. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 1999;192:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S0010-8545(99)00080-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Da Ros, T. & Prato, M. Medicinal chemistry with fullerenes and fullerene derivatives. Chemical Communications, 663–669 (1999).

- 19.Diederich F, Thilgen C. Covalent fullerene chemistry. Science. 1996;271:317–323. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kräutler B. The Chemistry of the Fullerenes. Von A. Hirsch. Thieme, Stuttgart, 1994. 203 S., Broschur 80.00 DM. – ISBN 3-13-136801-2. Angewandte Chemie. 1995;107:1654–1654. doi: 10.1002/ange.19951071346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson, S. R. et al. In Fullerenes: Chemistry, Physics, and Technology (eds K. M. Kadish & R. S. Ruoff) Ch. 3, 91-176 (John Wiley and Sons (2000).

- 22.Wilson LJ. Medical applications of fullerenes and metallofullerenes. The Electrochemical Society Interface. 1999;8:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen AW, Wilson SR, Schuster DI. Biological applications of fullerenes. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 1996;4:767–779. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00081-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura E, Isobe H. Functionalized fullerenes in water. The first 10 years of their chemistry, biology, and nanoscience. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2003;36:807–815. doi: 10.1021/ar030027y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch A. Addition Reactions of Buckminsterfullerene (C60) Synthesis. 1995;1995:895–913. doi: 10.1055/s-1995-4046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirsch A. The Chemistry of the Fullerenes: An Overview. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1993;32:1138–1141. doi: 10.1002/anie.199311381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirsch, A. in Fullerenes and Related Structures Vol. 199 Topics in Current Chemistry (ed Andreas Hirsch) Ch. 1, 1-65 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, (1999).

- 28.Maggini M, Scorrano G, Prato M. Addition of azomethine ylides to C60: synthesis, characterization, and functionalization of fullerene pyrrolidines. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1993;115:9798–9799. doi: 10.1021/ja00074a056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prato M, Maggini M. Fulleropyrrolidines: A family of full-fledged fullerene derivatives. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1998;31:519–526. doi: 10.1021/ar970210p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tat FT, et al. A new fullerene complexation ligand: N-pyridylfulleropyrrolidine. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2004;69:4602–4606. doi: 10.1021/jo049671w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friedman SH, et al. Inhibition of the hiv-1 protease by fullerene derivatives - model-building studies and experimental-verification. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1993;115:6506–6509. doi: 10.1021/ja00068a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DaRos T, Prato M, Novello F, Maggini M, Banfi E. Easy access to water-soluble fullerene derivatives via 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions of azomethine ylides to C60. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1996;61:9070–9072. doi: 10.1021/jo961522t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakamura E, Tokuyama H, Yamago S, Shiraki T, Sugiura Y. Biological activity of water-soluble fullerenes. Structural dependence of DNA cleavage, cytotoxicity, and enzyme inhibitory activities including HIV-protease inhibition. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 1996;69:2143–2151. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.69.2143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson, S., Kadish, K. & Ruoff, R. The Fullerene Handbook. Wiley New York, 437-465 (2000).

- 35.Castro E, Garcia AH, Zavala G, Echegoyen L. Fullerenes in biology and medicine. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2017;5:6523–6535. doi: 10.1039/C7TB00855D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Illescas BM, Rojo J, Delgado R, Martín N. Multivalent Glycosylated Nanostructures To Inhibit Ebola Virus Infection. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2017;139:6018–6025. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b01683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staudenmaier L. Verfahren zur Darstellung der Graphitsäure. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 1898;31:1481–1487. doi: 10.1002/cber.18980310237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen C-H, et al. Effective Synthesis of Highly Oxidized Graphene Oxide That Enables Wafer-scale Nanopatterning: Preformed Acidic Oxidizing Medium Approach. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:3908. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04139-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Diederich F, et al. The Higher Fullerenes: Isolation and Characterization of C76, C84, C90, C94, and C70O, an Oxide of D5h-C70. Science. 1991;252:548–551. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5005.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wood JM, et al. Oxygen and methylene adducts of C60 and C70. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113:5907–5908. doi: 10.1021/ja00015a080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalsbeck WA, Thorp HH. Electrochemical reduction of fullerenes in the presence of O2 and H2O: Polyoxygen adducts and fragmentation of the C60 framework. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry and Interfacial Electrochemistry. 1991;314:363–370. doi: 10.1016/0022-0728(91)85451-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor R, et al. Degradation of C60 by light. Nature. 1991;351:277. doi: 10.1038/351277a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Creegan KM, et al. Synthesis and characterization of C60O, the first fullerene epoxide. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:1103–1105. doi: 10.1021/ja00029a058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vassallo AM, Pang LSK, Cole-Clarke PA, Wilson MA. Emission FTIR study of C60 thermal stability and oxidation. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113:7820–7821. doi: 10.1021/ja00020a086. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elemes Y, et al. Reaction of C60 with Dimethyldioxirane—Formation of an Epoxide and a 1,3-Dioxolane Derivative. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 1992;31:351–353. doi: 10.1002/anie.199203511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weisman RB, Heymann D, Bachilo SM. Synthesis and Characterization of the “Missing” Oxide of C60: [5,6]-Open C60O. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2001;123:9720–9721. doi: 10.1021/ja016267v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hawkins JM, et al. Organic chemistry of C60 (buckminsterfullerene): chromatography and osmylation. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1990;55:6250–6252. doi: 10.1021/jo00313a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkins JM, Meyer A, Lewis TA, Loren S, Hollander FJ. Crystal Structure of Osmylated C60: Confirmation of the Soccer Ball Framework. Science. 1991;252:312–313. doi: 10.1126/science.252.5003.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawkins JM, Loren S, Meyer A, Nunlist R. 2D nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of osmylated C60. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1991;113:7770–7771. doi: 10.1021/ja00020a054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sommer T, Roth P. High-Temperature Oxidation of Fullerene C60 by Oxygen Atoms. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 1997;101:6238–6242. doi: 10.1021/jp971224f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dattani R, et al. Fullerene oxidation and clustering in solution induced by light. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2015;446:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng J-P, Mou C-Y, Han C-C. Oxidation of Fullerenes by Ozone. Fullerene Science and Technology. 1997;5:1033–1044. doi: 10.1080/15363839708013315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macovez R, et al. Ultraslow Dynamics of Water in Organic Molecular Solids. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:4941–4950. doi: 10.1021/jp4097138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tajima Y, Takeshi K, Shigemitsu Y, Numata Y. Chemistry of Fullerene Epoxides: Synthesis, Structure, and Nucleophilic Substitution-Addition Reactivity. Molecules. 2012;17:6395. doi: 10.3390/molecules17066395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dreyer DR, Park S, Bielawski CW, Ruoff RS. The chemistry of graphene oxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:228–240. doi: 10.1039/B917103G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Enotiadis A, Angjeli K, Baldino N, Nicotera I, Gournis D. Graphene-Based Nafion Nanocomposite Membranes: Enhanced Proton Transport and Water Retention by Novel Organo-functionalized Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. Small. 2012;8:3338–3349. doi: 10.1002/smll.201200609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pavlidis IV, Patila M, Bornscheuer UT, Gournis D, Stamatis H. Graphene-based nanobiocatalytic systems: recent advances and future prospects. Trends Biotechnol. 2014;32:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kudanga T, Nemadziva B, Le Roes-Hill M. Laccase catalysis for the synthesis of bioactive compounds. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2017;101:13–33. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7987-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh RL, Singh PK, Singh RP. Enzymatic decolorization and degradation of azo dyes – A review. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 2015;104:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vileno B, et al. Spectroscopic and Photophysical Properties of a Highly Derivatized C60 Fullerol. Advanced Functional Materials. 2006;16:120–128. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200500425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lotya M, et al. Liquid Phase Production of Graphene by Exfoliation of Graphite in Surfactant/Water Solutions. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:3611–3620. doi: 10.1021/ja807449u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Spyrou K, et al. Towards Novel Multifunctional Pillared Nanostructures: Effective Intercalation of Adamantylamine in Graphene Oxide and Smectite Clays. Advanced Functional Materials. 2014;24:5841–5850. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201400975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mitsari E, Romanini M, Zachariah M, Macovez R. Solid State Physicochemical Properties and Applications of Organic and Metallo-Organic Fullerene Derivatives. Curr. Org. Chem. 2016;20:645–661. doi: 10.2174/1385272819666150730220449. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuzmany H, Pfeiffer R, Hulman M, Kramberger C. Raman spectroscopy of fullerenes and fullerene-nanotube composites. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society a-Mathematical Physical and Engineering Sciences. 2004;362:2375–2406. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bethune DS, Meijer G, Tang WC, Rosen HJ. The vibrational Raman spectra of purified solid films of C60 and C70. Chemical Physics Letters. 1990;174:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(90)85335-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Talyzin, A. New fullerene materials obtained in solution and by high pressure high temperature treatment PhD thesis thesis, Uppsala University (2001).

- 67.Birkett PR, et al. The Raman spectra of C60Br6 C60Br8 and C60Br24. Chemical Physics Letters. 1993;205:399–404. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(93)87141-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jing D, Pan Z. Molecular vibrational modes of C60 and C70 via finite element method. European. Journal of Mechanics - A/Solids. 2009;28:948–954. doi: 10.1016/j.euromechsol.2009.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kroto HW, Allaf AW, Balm SP. C60 - Buckminsterfullerene. Chemical Reviews. 1991;91:1213–1235. doi: 10.1021/cr00006a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fusco C, Seraglia R, Curci R, Lucchini V. Oxyfunctionalization of Non-Natural Targets by Dioxiranes. 3.1 Efficient Oxidation of Buckminsterfullerene C60 with Methyl(trifluoromethyl)dioxirane. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1999;64:8363–8368. doi: 10.1021/jo9913309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.He H, Zheng L, Jin P, Yang M. The structural stability of polyhydroxylated C60(OH)24: Density functional theory characterizations. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry. 2011;974:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.comptc.2011.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Arrais A, Diana E. Highly Water Soluble C60 Derivatives: A New Synthesis. Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures. 2003;11:35–46. doi: 10.1081/FST-120018667. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spyrou K, et al. A novel route towards high quality fullerene-pillared graphene. Carbon. 2013;61:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ginzburg BM, Tuichiev S, Tabarov SK, Shepelevskii AA, Shibaev LA. X-ray diffraction analysis of C60 fullerene powder and fullerene soot. Technical Physics. 2005;50:1458–1461. doi: 10.1134/1.2131953. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zachariah M, et al. Water-Triggered Conduction Mediated by Proton Exchange in a Hygroscopic Fulleride and Its Hydrate. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2015;119:685–694. doi: 10.1021/jp509072u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Macovez R, et al. Hopping Conductivity and Polarization Effects in a Fullerene Derivative Salt. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2014;118:12170–12175. doi: 10.1021/jp503298e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu L-H, Lee Y-T, Chen H-W, Chiang LY, Huang H-C. The possible mechanisms of the antiproliferative effect of fullerenol, polyhydroxylated C60, on vascular smooth muscle cells. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;123:1097–1102. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mastorakis, N. E., Kluev, V. V. & Koruga, D. Advances in simulation, systems theory and systems engineering. 117–122 (WSEAS Press, 117-122) (2002).

- 79.Yang XL, Fan CH, Zhu HS. Photo-induced cytotoxicity of malonic acid [C60]fullerene derivatives and its mechanism. Toxicology in Vitro. 2002;16:41–46. doi: 10.1016/S0887-2333(01)00102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gharbi N, et al. [60]Fullerene is a Powerful Antioxidant in Vivo with No Acute or Subacute Toxicity. Nano Letters. 2005;5:2578–2585. doi: 10.1021/nl051866b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bogdanović G, et al. Modulating activity of fullerol C60(OH)22 on doxorubicin-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicology in Vitro. 2004;18:629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Isakovic A, et al. Distinct Cytotoxic Mechanisms of Pristine versus Hydroxylated Fullerene. Toxicological Sciences. 2006;91:173–183. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sayes CM, et al. Nano-C60 cytotoxicity is due to lipid peroxidation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:7587–7595. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tian W-d, Chen K, Ma Y-q. Interaction of fullerene chains and a lipid membrane via computer simulations. RSC Advances. 2014;4:30215–30220. doi: 10.1039/C4RA04593A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ektessabi AM, Hakamata S. XPS study of ion beam modified polyimide films. Thin Solid Films. 2000;377-378:621–625. doi: 10.1016/S0040-6090(00)01444-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shin J-W, Jeun J-P, Kang P-H. Surface modification and characterization of N+ ion implantation on polyimide film. Macromolecular Research. 2010;18:227–232. doi: 10.1007/s13233-010-0310-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Herrera-Alonso M, Abdala AA, McAllister MJ, Aksay IA, Prud’homme RK. Intercalation and stitching of graphite oxide with diaminoalkanes. Langmuir. 2007;23:10644–10649. doi: 10.1021/1a0633839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moses PR, et al. Chemically modified electrodes .9. X-ray photoelectron-spectroscopy of alkylamine-silanes bound to metal-oxide electrodes. Analytical Chemistry. 1978;50:576–585. doi: 10.1021/ac50026a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dimos K, et al. Naphthalene-based periodic nanoporous organosilicas: I. Synthesis and structural characterization. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials. 2012;158:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Legerská B, Chmelová D, Ondrejovič M. In Nova Biotechnologica et Chimica. 2016;15:90. doi: 10.1515/nbec-2016-0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Upadhyay P, Shrivastava R, Agrawal PK. Bioprospecting and biotechnological applications of fungal laccase. 3 Biotech. 2016;6:15. doi: 10.1007/s13205-015-0316-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Patila, M., Kouloumpis, A., Gournis, D., Rudolf, P. & Stamatis, H. Laccase-Functionalized Graphene Oxide Assemblies as Efficient Nanobiocatalysts for Oxidation Reactions. Sensors16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Teerapatsakul C, Parra R, Keshavarz T, Chitradon L. Repeated batch for dye degradation in an airlift bioreactor by laccase entrapped in copper alginate. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation. 2017;120:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2017.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Phetsom J, Khammuang S, Suwannawong P, Sarnthima R. Copper-alginate encapsulation of crude laccase from Lentinus polychrous Lev. and their effectiveness in synthetic dyes decolorizations. Journal of Biological Sciences. 2009;9:573–583. doi: 10.3923/jbs.2009.573.583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patila M, et al. Graphene oxide derivatives with variable alkyl chain length and terminal functional groups as supports for stabilization of cytochrome c. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2016;84:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]