Abstract

Background

International tourism increased from 25 million tourist arrivals in 1950 to over 1.3 billion in 2017. These travelers can be exposed to (multi) resistant microorganisms, may become colonized, and bring them back home. This systematic review aims to identify the carriage rates of multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales (MDR-E) among returning travelers, to identify microbiological methods used, and to identify the leading risk factors for acquiring MDR-E during international travel.

Methods

Articles related to our research question were identified through a literature search in multiple databases (until June 18, 2019) - Embase, Medline Ovid, Cochrane, Scopus, Cinahl, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Results

Out of 3211 potentially relevant articles, we included 22 studies in the systematic review, and 12 studies in 7 random-effects meta-analyses. Highest carriage rates of MDR-E were observed after travel to Southern Asia (median 71%), followed by travel to Northern Africa (median 42%). Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) were identified in 5 out of 22 studies, from a few patients. However, in only eight out of 22 studies (36.4%) the initial laboratory method targeted detection of the presence of CPE in the original samples. The risk factor with the highest pooled odds ratio (OR) for MDR-E was travel to Southern Asia (pooled OR = 14.16, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 5.50 to 36.45), followed by antibiotic use during travel (pooled OR = 2.78, 95% CI = 1.76 to 4.39).

Conclusions

Risk of acquiring MDR-E while travelling increases depending on travel destination and if antibiotics are used during travel. This information is useful for the development of guidelines for healthcare facilities with low MDR-E prevalence rates to prevent admission of carriers without appropriate measures. The impact of such guidelines should be assessed.

Keywords: Travel, Enterobacteriaceae, Enterobacterales, Systematic review, Meta-analysis, Antimicrobial resistance, Epidemiology, Microbiology, Beta-lactamases

Introduction

Multidrug resistance, defined as acquired non-susceptibility to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories, of clinically important bacteria is recognized as a major threat for human health worldwide. However, remarkable geographical differences in prevalence and trends exist [1, 2]. Multidrug-resistant (MDR) Enterobacterales (MDR-E) that produce extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) and/or carbapenemases are of most concern, since these bacteria are able to colonize the human gut and may cause a variety of infections that subsequently require more complicated treatments [3, 4]. Fecal colonization rates with ESBL-producing Enterobacterales (ESBL-E) are estimated to be 14% among healthy individuals worldwide, with an annual increase from 1990 to 2015 of around 5% [5]. These rates are higher in the Mediterranean, the West Pacific, Africa and South-East Asia, and lower in Northern Europe and North America [5]. The carriage rate of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales (CPE) in healthy individuals is estimated to be low or absent, although only few studies have included healthy people in a community setting. In East-London, 200 community stool samples were screened and no CPE was identified [6]. CPE are mostly seen in people with exposure to healthcare [7]. In some countries, however, CPE are widespread in the environment [8, 9].

When people travel from low-prevalence areas to areas with a higher prevalence of ESBL-E or CPE in the community, such strains may become part of their gut flora and then carried to the travelers’ home country. This risk is on the rise, since international tourism has increased from 25 million tourist arrivals in 1950, to 1326 million tourist arrivals in 2017 with an expected annual growth of 3.3% [10, 11]. This means that by 2030, 1.8 billion tourist arrivals will be reported. Additionally, between 2015 and 2016, travel to Oceania, Africa and South-East Asia increased the most, by 9.4, 8.1 and 7.8% respectively [10].

Tängdén et al. first reported on travel and acquisition of ESBL-E in 2010 [12]. Since then, numerous reports and several systematic reviews have been published on the relationship between fecal colonization with MDR-E and international travel [13, 14]. However, for healthcare settings, especially those with a low prevalence of MDR-E, it is still unclear how to translate this knowledge into policies or guidelines for infection control and patient care. In addition, it is unclear how travel clinics or general practitioners can use the existing information for pre-travel advice. This review adds to the existing literature by performing an extensive systematic review to describe carriage rates of MDR-E among returning travelers, to describe microbiological methods used, and to perform a meta-analysis in order to identify the leading risk factors for acquiring MDR-E during international travel.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analyses followed the guidelines presented in the PRISMA statement (see Additional file 1) [15]. Moreover, this study is an update and extension of the study published by Hassing et al. (Prospero registration number CRD42015024973), whose database search was conducted on August 17, 2015 [16].

Study selection

Articles related to our research question were identified through a literature search in multiple databases (until June 18, 2019) ─ Embase, Medline Ovid, Cochrane, Scopus, Cinahl, Web of Science, and Google Scholar (see Additional file 2). The search was not limited by language, date of publication, country of publication or study design.

We used the following inclusion criteria during the study selection: (i) related to foreign travel, (ii) reports on systematic and selective screening for the carriage of ESBL-E and/or CPE among travelers without signs of infections when performing the screening, and (iii) report on fecal Enterobacterales carriage. We excluded studies related to nonhuman infections, hospital studies, studies about symptomatic patients (e.g., travelers’ diarrhea [TD]), conference abstracts, letters to the editor, commentaries, weekly reports, and editorials. First, titles and abstracts of all retrieved citations were screened independently by KM and AFV. After this screening, KM, AFV and BB performed a second screening based on the full-text. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Reference lists of reviews and systematic reviews on the same subject, which were identified during the literature search, were screened to identify additional studies that had been missed by our search strategy.

Data extraction

We designed a data extraction form and pilot-tested it on two randomly selected articles, and redefined it according to the outcomes. The following data were extracted by AFV and BB: first author, journal, year published, country, study design, study period, where were the participants recruited (e.g. travel agency, vaccination clinic), total number of participants, mean age, percentage female, mean duration of travel, sample method, microorganism(s) studied, co-travelers or household members included, percentage of carriage before and after travel, acquisition rate, acquisition rate to household members, acquisition rates for each United Nations geographical region, laboratory methods (e.g. species determination, phenotypic approaches, molecular approaches), risk factors and protective factors identified in multivariable models; and corresponding odds ratio, 95% confidence interval and P-value. The completed data extraction form was sent to the corresponding author of the original manuscript to verify the extracted data, and to gain additional information if relevant. In case we did not receive any response after the given deadline (i.e. 2 weeks), a reminder was sent. If no response was received and crucial information was missing, the study was excluded.

Data analysis

Carriage rates of multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales by travel destination

The following geographical classification was used, based on the United Nations geographical regions: (i) Southern Asia, (ii) Asia except Southern Asia, (iii) Northern Africa, (iv) Sub-Saharan Africa, (v) South and Central America, (vi) North America, (vii) Europe, (viii) Oceania (see Additional file 3). Carriage rates immediately after return were grouped into the following 5 categories, and for a visual presentation of the results a color was added from green to dark red: (i) 0–20%, low, green; (ii) 21–40%, moderate, yellow; (iii) 41–60%, high, orange; (iv) 61–80%, very high, red; (v) 81–100%, extremely high, dark red.

Meta-analysis

All risk factors extracted from the articles for which an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was reported were grouped into eight categories: (i) diarrhea during travel, (ii) antibiotic use during travel, (iii) travel to Southern Asia, (iv) behavior during travel, (v) food consumption during travel, (vi) length of stay, (vii) sex, and (viii) age.

The meta-analyses for each category were performed using StatsDirect statistical software (Altrincham, United Kingdom) including the random-effects model of DerSimonian and Laird [17]. We used a random-effects model to limit the influence of heterogeneity. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Publication bias was examined visually with use of funnel plots, and assessed with the Egger and Begg-Mazumdar indicators [18, 19].

Study quality

The methodological quality was assessed for all included studies using the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) guideline [20]. Studies with a score ≤ 15 out of 33 points were considered to be of relatively low methodological quality, studies receiving a quality score of 16–19 points were considered as of moderate quality, and studies with ≥20 points were considered to have a relatively high study quality. Study quality was not considered an exclusion criterion.

Results

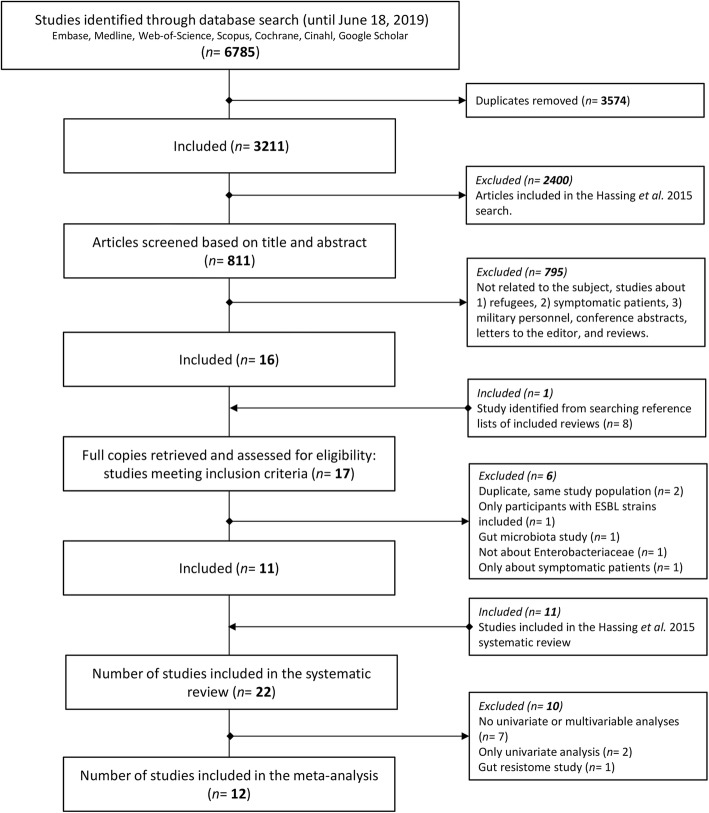

The literature search identified 3211 non-duplicate articles, of which 811 articles were potentially relevant for this current study (Fig. 1). Titles and abstracts of these 811 articles were screened, which resulted in the exclusion of 795 articles (98%). One additional study was included after searching the reference lists of reviews of interest. The remaining 17 articles underwent a second screening based on the full-text, after which 6 articles were excluded (35.3%) (Fig. 1). The remaining 11 studies were added to the 11 previously identified by Hassing et al., and used in his review. Hence, in total 22 articles were included in this systematic review [16]. Of the 22 included articles, 12 were included in random-effects meta-analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of study selection

For the 22 included studies, the corresponding author was contacted to provide feedback on extracted data or to request additional information. The corresponding authors of all studies (100%) responded to our request to provide feedback on the extracted data. For three studies, we requested additional information on the multivariable analysis since crucial information was missing. Unfortunately, additional information was not received and these studies were therefore excluded from the random-effects meta-analyses.

Study characteristics

All 22 included studies were prospective cohort studies. The studies were conducted in Western Europe (n = 17, 77.3%), North America (n = 2, 9.1%), Japan (n = 2, 9.1%), and Australia (n = 1, 4.5%). The characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 1. Fifteen studies investigated travelers visiting a travel or vaccination clinic, one study investigated hospital staff and contacts, one study investigated healthcare students, one study investigated business travelers, one study investigated Hajj pilgrims, and two studies did not state the type of study population. The studies by van Hattem et al. and Arcilla et al. both investigated participants enrolled in the COMBAT-study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01676974); van Hattem et al. reported on CPE acquisition, and Arcilla et al. on ESBL-E acquisition [36, 37].

Table 1.

Study characteristics of the 22 included studies

| Study | Year | Country | Study period | Population characteristic | Study sizea | Proportion of MDR E. colie in post-travel isolates | Sample time (range) before/after travel | Median duration of travel in days (range) | Follow-up of carriage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kennedy [21] | 2010 | Australia | January 2008–April 2009 | Hospital staff and contacts | 102 | > 92% E. colib | Within 2 weeks before and after | 21 (9–135) | 6 months |

| Tängdén [12] | 2010 | Sweden | November 2007–January 2009 | Travel clinic | 100 | 100% E. coli (24/24b) | Unknown | 14 (7–182) | 6 months |

| Weisenberg [22] | 2012 | United States | July 2009–February 2010 | Travel clinic | 28 | E. coli 100% (7/7b) | 1 week before/within 1 week after | 14 (8–42) | None |

| Östholm-Balkhed* [23, 24] | 2013 | Sweden | September 2008–April 2009 | Vaccination clinic | 231 | 90% E. coli (104/116)b | 15 (1–114) days/ 3 (0–191) days | 16 (4–119) | 12 months |

| Paltansing* [25] | 2013 | The Netherlands | March 2011–September 2011 | Travel clinic | 370 | 92% E. coli (146/158)c | Immediately before and after | 21 (6–90) | 6 months |

| Kuenzli* [26] | 2014 | Switzerland | December 2012–October 2013 | Travel clinic | 190 | 98% E. coli (157/161b) | Week before/directly after | Mean; 18 (5–35) | None |

| von Wintersdorff [27] | 2014 | The Netherlands | November 2010–August 2012 | Travel clinic | 122 | ND | Before and immediately after | 21 (5–240) | None |

| Angelin* [28] | 2015 | Sweden | April 2010–January 2014 | Healthcare students | 99 | 100% E. coli (35/35c) | Close to departure/ 1–2 weeks after return | 45 (13–365) | None |

| Kantele* [29] | 2015 | Finland | March 2009–February 2010 | Travel clinic | 430 | 97% E. coli (94/97b) | Before/first (or second) stool after | Mean; 19 (4–133) | 12 months |

| Lübbert [30] | 2015 | Germany | May 2013–April 2014 | Travel clinic | 205 | 92% E. coli (58/63b) | Before/within 1 week after | 21 (2–218) | 6 months |

| Ruppé* [31] | 2015 | France | February 2012–April 2013 | Vaccination centers | 574 | 93% E. coli (491/526b) | Within 1 week before and after | 20 (IQR 15–30) | 12 months |

| Bernasconi [32] | 2016 | Switzerland | January 2015–August 2015 | Unknown | 38 | 90% E. coli (26/29b) | Within 1 week before and after | Mean; 15 (8–35) | 6 months |

| Mizuno [33] | 2016 | Japan | September 2012–March 2015 | Business travelers | 57 | ND | Before and at time of return | > 6 months | None |

| Reuland* [34] | 2016 | The Netherlands | April 2012–April 2013 | Vaccination clinic | 445 | 97% E. coli (95/98b) | Before/within 2 weeks after | Mean; 14 (1–105) | None |

| Vading* [35] | 2016 | Sweden | April 2013–May 2015 | Travel clinic | 188 | 97% E. coli (65/67b) | Unknown | 14 (IQR 8–20) | 10 to 26 months |

| van Hattemd [36] | 2016 | The Netherlands | November 2012–November 2013 | Travel clinic | 2001 | 60% E. coli (3/5b) | Before/immediately and 1 month after travel | 20 (IQR 15–25) | 12 months |

| Arcilla*d [37] | 2017 | The Netherlands | November 2012–November 2013 | Travel clinic | 2001 | 88% E. coli (759/859b) | Before/immediately and 1 month after travel | 20 (IQR 15–25) | 12 months |

| Leangapichart* [38] | 2017 | France | Hajj 2013 & 2014 | Hajj pilgrims | 218 | ND | Just before departure and after the Hajj just before return | 22 and 24 | None |

| Peirano* [39] | 2017 | Canada | January 2012–July 2014 | Travel clinic | 116 | 100% E. coli (124/124b) | Before /within 1 week after | 10–38 | 6 months |

| Bevan [40] | 2018 | United Kingdom | March 2015–June 2016 | University and university hospital | 18 | 100% E. coli (16/16) | As close to the time of sample submission and after | 21, mean 27 | Up to 12 months |

| Nakayama [41] | 2018 | Japan | June 2015–August 2016 | Unknown | 19 | 100% E. coli | Before and up to 2 weeks after | 2–12 days | None |

| Schaumburg* [42] | 2019 | Germany/the Netherlands | October 2016–March 2018 | Vaccination center | 132 | ESBL-producing Enterobacterales | Up to 1 week before departure, during travel and up to 1 week after return | Mean: 18.7, maximum of six weeks | 6 months (137–420 days after return) |

Abbreviations: E. coli, Escherichia coli; MDR Multidrug-resistant; ND No data; *, included in the meta-analyses

a Number of travelers who provided pre-travel and post-travel samples

b MDR microorganisms newly acquired during travel

c Data about post-travel samples

d Reported on the same study population, however, van Hattem et al. reported on CPE acquisition, and Arcilla et al. on ESBL-E acquisition

e Including ESBL-producing E. coli and carbapenemase-producing E. coli

The median study size was 160 participants, ranging from 18 to 2001 participants, and the median age of participants ranged from 25 years to 66 years, with participants included from 0 to 84 years old. The median proportion of women was 61%, ranging from 26 to 78%; one study did not report the gender of the participants. Most studies had participants with a similar median duration of travel, ranging from median 14 to 21 days. However, the study investigating healthcare students had a median duration of travel of 45 days (13–365) [28] and in the study investigating business travelers, participants travelled for at least 6 months [33]. Sample collection in the included studies was via stool sample (n = 14, 63.6%), rectal swab (n = 6, 27.3%), a rectal swab or a stool sample (n = 1, 4.5%), or a rectal or perianal swab (n = 1, 4.5%). Four studies also investigated co-travelers in addition to the study population [12, 29, 36, 37]. Three studies did not report on identification of microorganisms, and one study investigated a variety of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria: ESBL-E, CPE and colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Between the latter two groups, Enterobacter cloacae and Escherichia coli were the most frequently identified Enterobacterales, respectively. In all other studies, ESBL-positive E. coli was the most dominant MDR-E identified in post-travel samples.

Only one study clearly defined TD as more than 3 loose/liquid stools per 24 h or more frequently than normal for an individual [29] and one study referred to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition [42]. The other included studies just asked in questionnaires if the participant had experienced TD yes or no.

Microbiological methods

Enrichment was used in 12 out of 22 included studies (54.5%), all with a different composition, and 21 out of 22 included studies (95.5%) used selective agar plates, with 13 studies using ChromID ESBL (Table 2). The method most often used for antimicrobial susceptibility testing was the VITEK2 system (bioMérieux, 10 out of 22, 45.5%), and phenotypic confirmation of ESBL-production was most often performed by disk-diffusion (12 out of 22, 54.5%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Microbiological methods of the 22 included studies

| Study | Enrichment | Selective media | AST | Confirmation of ESBL | CPE-targeted isolation method | CPE screening in isolates | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kennedy [21] | Yes | BHI broth with vancomycin disk | Yes | MacConkey with NAL disk, horse BA with gentamicin, ChromID ESBL | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion, PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | No | No |

| Tängdén [12] | Yes | LB broth with cefotaxime | Yes | MacConkey with cefotaxime and ceftazidime disks | E-test | Disk-diffusion | No | No, only carbapenem AST |

| Weisenberg [22] | No | NA | Yes | MacConkey with cefpodoxime | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion, PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | No | Yes, PCR for blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-48, blaNDM |

| Östholm-Balkhed [23] | No | NA | Yes | ChromID ESBL, chromogenic UTI agar with antibiotic disks | E-test | E-test, PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | No | No, only carbapenem AST |

| Paltansing [25] | Yes | TSB with cefotaxime and vancomycin | Yes | ChromID ESBL | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion, microarray for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | No | Yes, microarray to detect blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-48, blaNDM-1 |

| Kuenzli [26] | Yes | TSB with 0.5% sodium chloride | Yes | ChromID ESBL, MacConkey with ertapenem disk | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion, selection of isolates: microarray for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | Yes | Yes, modified Hodge, selection of isolates: microarray for blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-48, blaNDM |

| von Wintersdorff [27] | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | PCR for blaCTX-M | No | Yes, PCR for blaNDM |

| Angelin [28] | No | NA | Yes | ChromID ESBL | Disk-diffusion | E-test | No | Yes, disk-diffusion for blaOXA-48 and blaOXA-181 and CT103XL microarray |

| Kantele [29] | No | NA | Yes | ESBL, KPC (CHROMagar) | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion | Yes | No, only AST |

| Lübbert [30] | No | NA | Yes | CHROMagar ESBL, CHROMagar KPC plate | Microbroth dilution | E-test, PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | Yes | Yes, multiplex PCR for blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-48, blaNDM |

| Ruppé [31] | Yes | (1) BHI broth with cefotaxime; (2) BHI broth with ertapenem | Yes | (1) With and without enrichment: ChromID ESBL agar; without enrichment: bi-valve ESBL agar; (2) Drigalski agar with ertapenem and imipenem E-test | Disk-diffusion | PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M, and blaVEB | Yes | Yes, PCR for blaKPC, blaIMP, blaVIM, blaOXA-48, blaNDM |

| Bernasconi [32] | Yes | LB broth with a cefuroxime disk | Yes | BLSE, ChromID ESBL, Supercarba selective plates | Microdilution | CT103XL microarray | No | Yes, CT103XL microarray |

| Mizuno [33] | No | NA | Yes | ChromID ESBL | MicroScan Neg Combo 6.11 J panel | Disk-diffusion | No | No, only imipenem AST |

| Reuland [34] | Yes | TSB with ampicillin | Yes | EbSA ESBL agar, CLED agar with ciprofloxacin disk | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion, PCR for ESBL genes | No | Yes, ertapenem E-test, PCR for carbapenemase genes followed by sequencing |

| Vading [35] | Yes | LB broth with meropenem | Yes | In-house chromogenic base with cloxacillin and meropenem; without enrichment: ChromID ESBL | Disk-diffusion | Vitek2, Check-MDR microarray | Yes | Yes, Check-MDR microarray |

| van Hattem [36] | Yes | TSB with vancomycin | Yes | ChromID ESBL, chromID OXA-48 agar | VITEK2, E-test | Disk-diffusion, Identibac® AMR08 microarray | Yes | Yes, Identibac® AMR08 microarray and targeted PCR and DNA sequencing |

| Arcilla [37] | Yes | TSB with vancomycin | Yes | ChromID ESBL | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion | No | No |

| Leangapichart [38, 43, 44] | Yes | TSB | Yes | MacConkey with cefotaxime and Cepacia agar | Disk-diffusion | PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | No | No, only imipenem AST |

| Peirano [39] | No | NA | Yes | ChromID ESBL, chromID-CARBA SMART | VITEK2 | Disk-diffusion, PCR for blaTEM, blaSHV, and blaCTX-M | Yes | Partly, carbapenem AST, PCR for blaOXA |

| Bevan [40] | Yes | BHI broth with cefpodoxime disk | Yes | Oxoid ESBL brilliance agar, Oxoid UTI brilliance agar with cefpodoxime disk | NP | PCR for CTX-M ESBL genes | No | Yes, WGS and bioinformatics screening |

| Nakayama [41] | No | NA | Yes | CHROMagar ECC with 1 μg/mL cefotaxime | Disk diffusion | Double-disk synergy test, PCR for ESBL genes | No | No, only meropenem AST |

| Schaumburg [42] | No | NA | Yes | ChromID-ESBL, chromID-CARBA | VITEK2 | Double-disk diffusion | Yes | Yes, modified Hodge test and PCR for blaKPC2–15, blaVIM1–37, blaNDM1–7, blaOXA-48, blaOXA-181 |

Abbreviations: NAL Nalidixic acid; NA Not applicable; NR Not reported; AST Antimicrobial susceptibility testing; TSB Tryptic soy broth; ESBL Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase; KPC Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase; BA Blood agar; LB Luria-Bertani; BHI Brain heart infusion; CLED Cystine lactose electrolyte-deficient medium; SMART Solutions to manage the antimicrobial resistance threat; NP Not performed; WGS Whole-genome sequencing

In eight out of 22 studies (36.4%) the initial laboratory method targeted detection of the presence of CPE in the original samples, i.e. a selective agar plate method without a pre-enrichment with a broth containing second or third generation cephalosporins (Table 2) [26, 29–31, 35, 36, 39, 42]. In only 4 of these eight studies, a CPE was found [26, 31, 36, 42]. In 13 out of the 22 studies (59.1%), screening for CPE was carried out in isolates or directly on the specimen by a variety of phenotypic and genotypic methods (Table 2). In other studies, carbapenem susceptibility testing was partly or not performed, or isolates with reduced susceptibility to carbapenems were not further analyzed. Therefore, in those studies CPE could have remained unidentified.

Carriage of multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales

International travelers

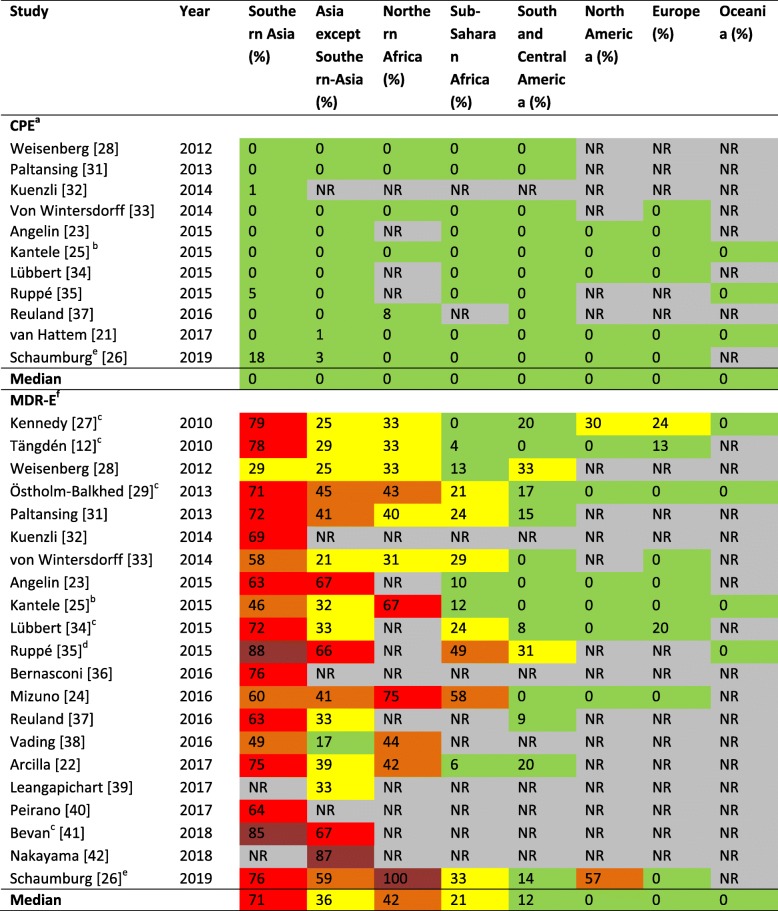

Table 3 shows the rates of travelers acquiring CPE, or MDR-E (i.e. without CPE) during international travel. It was not possible to report ESBL-E separate from MDR-E, since multiple studies, when reporting prevalence rates, combined ESBL-E and for example AmpC-producing Enterobacterales. Highest carriage rates of MDR-E were observed after travel to Southern Asia (Table 3), with proportions ranging from 29 to 88%, with as median 71%. Second was travel to Northern Africa, with proportions ranging from 31 to 100%, with as median 42%. CPE carriage was only identified in 5 studies [26, 31, 34, 36, 42], and mainly found in E. coli. Carbapenemases identified were IMI-2, NDM, NDM-1, NDM-1/2, NDM-7, OXA-48, OXA-181 and OXA-244.

Table 3.

Proportion of travelers who acquired a resistant microorganism after international travel

Abbreviations: NR Not reported; CPE Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales; MDR-E Multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales

Colors: (i) 0–20%, low, green; (ii) 21–40%, moderate, yellow; (iii) 41–60%, high, orange; (iv) 61–80%, very high, red; (v) 81–100%, extremely high, dark red.

a Only noted for studies that used methods to be able to identify CPE as described in Table 2.

b Travelers who visited several regions are arranged to the region in which they spend the most time.

c Travelers who visited several regions are arranged to all of the visited regions.

d 42 travelers visited several countries in Asia and may therefore be arranged in several columns in the table; 28 of them acquired a MDR-E.

e Carriage rates after travel from travelers to Southern-Asia (CPE: 3 out of 17, ESBL: 13 out of 17), Asia except Southern Asia (CPE: 1 out of 29, ESBL: 17 out of 29), Northern Africa (ESBL: 3 out of 3) and Sub-Saharan Africa (ESBL: 9 out of 27) were received from the corresponding author.

f Not including CPE. It was not possible to report ESBL-E separate from MDR-E.

Household members

Acquisition of MDR-E from the traveler to a non-travelling household member was described by 3 studies [25, 36, 37]. In the study by Paltansing et al., 1 out of 11 (9.1%) household members carried the same ESBL-producing E. coli as the traveler [25]. In the study by Arcilla et al., 13 out of 168 (7.7%) household members carried a microorganism with the same ESBL group as the traveler [37]. When the authors estimated the transmission rate after introduction into a household using a Markov model, the probability of transmission was 12% (95% CI = 5 to 18%) [37]. In the study by van Hattem et al., acquisition of a blaOXA-244-positive E. coli from a traveler to a household member was highly suspected. Three months after travel a blaOXA-244-positive E. coli with a similar AFLP pattern was isolated from a fecal sample from a spouse and travel companion. All other fecal specimens from this household member were CPE negative, which suggested post-travel acquisition of the same bacterium [36].

Persistence of colonization and subsequent infections

Fourteen studies performed follow-up analysis of persistence of MDR-E colonization [12, 21, 24, 25, 29–32, 35–37, 39, 40, 42], ranging from 6 to 26 months (Table 1). The median reported persistence rate of acquired MDR-E at one, three, six and 12 months after return was 42.9, 22.4, 18.0 and 4.2% respectively. Arcilla et al. also reported on the rate of intermittent carriage of acquired MDR-E, which was 2.6% of all follow-up participants at 3 months, 3.0% at 6 months and 4.7% at 12 months [37]. Schaumburg et al. also calculated the median time of event-free survival for ESBL-E (i.e. time to first colonization with ESBL-E during travel), which was 8 days [42].

Five studies [12, 21, 30, 31, 35] investigated whether the colonizing pathogen caused clinical infection afterwards. Only a few clinical infections resulting from colonization with MDR-E have been reported. The study by Kennedy et al. reported one urinary tract infection (UTI) out of 50 follow-up participants caused by an E. coli with the same resistance pattern as the colonizing E. coli [21]. Ruppé et al. reported that eight out of 245 follow-up participants had contracted a UTI during the follow-up period, but no microbiological data was available to confirm that these infections were caused by the colonizing pathogen [31]. Studies by Lübbert et al., Tängdén et al. and Vading et al. reported no clinical infections in respectively 58, 21, and 56 follow-up participants [12, 30, 35].

Protective factors and risk factors

We identified 12 studies describing protective and/or risk factors for acquiring MDR-E during travel, obtained from multivariable analyses (see Additional file 4). The highest OR was reported for the risk factor TD (OR = 31.00, 95% CI = 2.70 to 358.10). Examples of identified protective factors were handwashing with soap before meals, a beach holiday, tap water consumption, and travel to various countries compared to traveling to Asia (see Additional file 4).

All identified risk factors, protective factors, and factors identified as non-significant in multivariable models were grouped into 8 categories. For these 8 categories, 7 meta-analyses were performed. For the category length of stay, three factors were identified. However, for one factor the confidence interval was missing. Therefore, for the category length of stay no meta-analysis was performed. The factor antibiotic use during travel was most frequently described (n = 13 times identified).

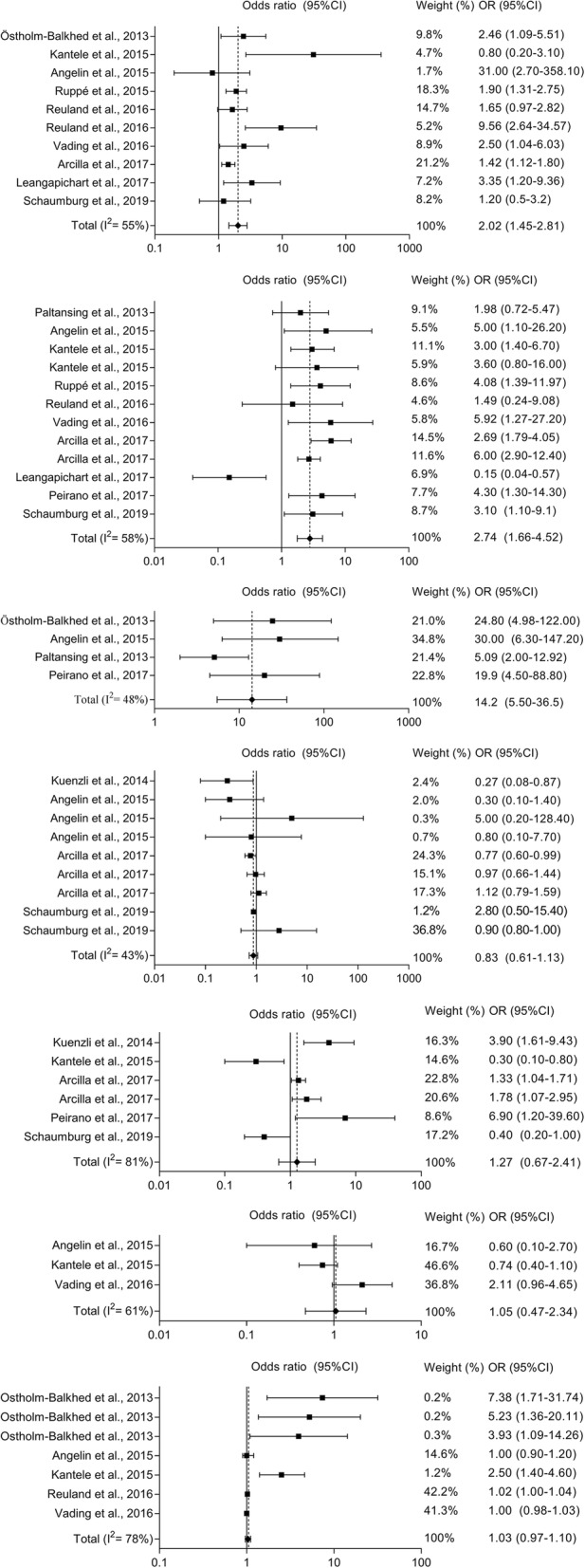

The risk factor with highest pooled OR was found to be travel to Southern Asia (pooled OR = 14.16, 95% CI = 5.50 to 36.45) (Fig. 2-c), followed by antibiotic use during travel (pooled OR = 2.78, 95% CI = 1.76 to 4.39) (Fig. 2-b) and TD (pooled OR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.45 to 2.81) (Fig. 2-a). The factors behavior during travel (Fig. 2-d), food consumption during travel (Fig. 2-e), male gender (Fig. 2-f), and older age (Fig. 2-g) were identified as non-significant factors. Publication bias indicators Begg-Mazumdar (Kendall’s tau) and Egger both showed a statistically significant result in the following meta-analyses: travel to Southern Asia, and older age (see Additional file 5). Funnel plots are available in Additional file 5.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of random-effects meta-analyses of risk factors for acquiring multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales during international travel (a to g appear from top to bottom). (a) Experienced diarrhea while travelling (i.e. TD); (b) antibiotic use during travel; c) travelled to Southern Asia; (d) behavior during travel (e.g. brought disposable gloves, consumed bottled water); (e) food consumption during travel (e.g. ice cream and pastry consumption, meals at street food stalls); (f) male gender; (g) older age

Study quality

A quality assessment was performed for all included studies; n = 22. Overall, the studies scored between 9 and 26 out of 33 points, with a median of 18 points. Six studies had a low methodological quality [22, 27, 28, 32, 33, 38, 41], seven a moderate methodological quality [12, 21, 23, 25, 26, 30, 36], and six studies a high methodological quality [29, 31, 34, 35, 37, 39, 40, 42].

Discussion

Summary of evidence

We identified that when travelling to Southern Asia (i.e. Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka) people are at highest risk of acquiring and carrying a MDR-E upon return. Though, acquisition of MDR-E when visiting Northern Africa or Asia except Southern Asia was also high (Table 3). Additionally, we showed that acquiring a CPE while travelling is still rare, which is supported by the findings of Jans et al. [45]. However, it should be emphasized that in most studies a culture method was used that was not specifically targeting CPE. Especially CPE with OXA-48-like carbapenemases may be missed [36]. The risk factors for acquiring MDR-E in order of those with the highest to those with the lowest pooled OR are: (i) travel to Southern Asia; (ii) antibiotic use during travel; and (iii) TD. Older age, sex, food consumption during travel and behavior during travel were found to be non-significant (Fig. 2). With this systematic review, we aimed to provide aggregated data on acquisition of MDR-E and risk factors for MDR-E acquisition during international travel, which can be useful for the development of guidelines and policies in areas with a low prevalence of MDR-E.

Travel to Asia, especially to India, is a known high risk for acquiring MDR-E. MDR-E are highly prevalent in this area because of the overuse of antibiotics, the lack of (clean) toilets and the lack of clean water. Hereby, bacteria can become resistant and are easily spread between people and to the environment. TD is associated with contaminated food or water, and is related to the lack of hygiene and sanitation [46]. Bacteria are responsible for the majority of cases [46]. TD in combination with antibiotic use does not only increase the risk of acquiring MDR-E, but also selects for antibiotic resistant bacteria [46–49]. Our results in combination with the studies by Kantele et al. highlight the need to avoid antibiotic use in mild to moderate TD [47–49]. Because most diarrheal episodes are self-limiting, it is only important to avoid dehydration [46]. Additionally, only one study used a clear definition of TD [29]. As described by Lääveri et al., the impact of the definition of TD is substantial on the results and conclusions [50].

Interestingly, food consumption – a known risk factor for TD and thus acquiring MDR-E – was identified as non-significant. It may be that, because of all warnings and available guides, people are aware of the risks and stopped eating food from street vendors, raw food, and stopped drinking tap water, milk from open containers and fountain drinks [51]. Alternatively, it is also possible that recall bias played a role in the questionnaires’ outcomes, and food consumption was rarely identified as a risk factor because people unknowingly eat risky food. In our opinion, this is more likely, as it may be difficult for travelers to determine if establishments adhere to food safety standards [52, 53].

Towards a guideline

Although in our opinion the aggregated data do support the implementation of additional recommendations that can be given by travel clinics and general practitioners to people before travelling, there are still a number of knowledge gaps that need be filled before national and international guidelines on infection control (screening and/or isolation) and patient care (adjustment of empiric treatment) for healthcare facilities can be developed. First, the proportion of people with recent travel history to a foreign country with increased risk of MDR-E acquisition among patients admitted to hospitals is currently unknown. Second, it is unknown whether the strains that are carried by travelers do spread in hospitals, although it is known that in general ESBL-E and CPE can be transmitted between patients and into the hospital environment, especially when contact precautions are not taken, which can lead to outbreaks [54]. The fact that not only strains, but also resistance genes on mobile genetic elements such as plasmids can spread, makes this knowledge gap even more difficult to resolve. The cost-effectiveness of a program that would include screening and subsequent isolation of recent travelers can therefore not be estimated with the currently available data, nor can the overall impact of such a program on healthcare workers, laboratories and patients. The threshold of a carriage rate after travel that warrants screening and/or isolation is also an unresolved issue, but is likely to be dependent on the local carriage rates. For example, when travelling to Sub-Saharan Africa, 17% of travelers acquire ESBL-E. For the Netherlands, a country with a carriage rate in the community of 5.3 to 9.9%, 17% can be considered as high [54]. However, for example in countries with higher community carriage rates, other approaches may be more applicable. Such policies would also require systematic surveillance of carriage rates amongst travelers, or of local carriage rates. The burden of disease of travel-related MDR-E is also unknown. Follow-up data on infections in travelers is scarce, as is data on phylogenetic groups (PG) of E. coli and virulence factors in general. The limited available data suggest that infections are rare, clones may belong to low-virulent sequence types, and the PG varies between studies [12, 25, 26, 30, 35, 40, 55]. Third, most studies were performed in Europe and included travelers who visited a travel clinic. Therefore, just a few studies included travelers who visited Europe. In addition, few travelers to North America or Oceania were included in the studies in this review, possibly due to travelers not seeing a travel clinic when visiting these continents. Travelers visiting friends and relatives abroad are also underrepresented, since they usually do not seek health advice in a travel clinic before travelling. Additional studies are needed to assess the risks of these groups of travelers.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is that it is an extensive literature search. In addition to the systematic review by Hassing et al., we performed meta-analyses to identify the main risk factors, looked more into detail to the laboratory methods and subsequent possibility to identify CPE and identified knowledge gaps. In addition, we performed an in-depth analysis about carriage rates (e.g. carriage rates of travelers, acquisition to household members and persistence of carriage).

This study has some limitations. First, the heterogeneity of included studies. We included studies performed in different countries and studying different types and groups of travelers. Additionally, the prevalence of MDR-E in each country is different and this was not incorporated in the risk factor analysis. To limit the influence of heterogeneity, in the meta-analysis we used a random effects model. Second, publication bias was present in several meta-analyses. Despite our extensive search for all available evidence, small studies with no effect are simply not performed and/or published. However, because of our extensive search, we think that the influence of publication bias to our results and conclusions is limited. Third, seven studies were included with a low methodological quality, of which 2 were included in the meta-analyses. These were relatively small studies, which did not have a big influence in weight on the pooled estimate. Therefore, we consider the influence of studies with a low methodological quality as limited.

Conclusion

This systematic review shows that travel to South Asia, together with antibiotic use and TD, are leading risk factors for acquiring MDR-E. It is advisable for travelers to contact a travel clinic in their home country before travel to be informed about TD and antibiotic use, and to limit self-prescribing of antibiotics and buying antibiotics over the counter during travel when suffering from TD. Acquisition of CPE during travel is still rare, but possibly underreported. The information in this review is useful for the development of guidelines for healthcare facilities with low MDR-E prevalence rates to prevent admission of potential carriers of MDR-E without appropriate measures. However, we identified a number of knowledge gaps that should be filled in before guidelines for healthcare facilities can be developed and implemented, since the impact of the measures cannot be estimated yet.

COVID-19

Currently, we are in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments are discouraging or forbidding travel of any kind, and calling on everyone to stay at home as much as possible. Additionally, several countries have implemented a full lockdown or shelter-in-place measures. Healthcare systems are severely affected. Furthermore, these measures have a significant impact on domestic and international travel. This also affects the spread of MDR-E: we expect a decreased transmission rate during this period due to the decrease in (inter)national travel. However, an increased use of antibiotics has also been observed. We expect that this, combined with overcrowding and a shortage of personal protective equipment in hospitals, will lead to an increase of local spread of MDR-E, and consequently, we expect an increased local prevalence of MDR-E in low-and-middle income countries and in Southern European countries. If in the second half of 2020 international travel is resumed due to relaxing of COVID-19 measures, we will see the results of this local spread. We expect that the proportion of travelers who acquire a resistant microorganism after international travel will increase after COVID-19. Future surveys will provide more insight in the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on travel-related spread of MDR-E.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1:. text file: The PRISMA Checklist.

Additional file 2:. text file: Literature search strategy – list of search terms.

Additional file 3:. text file: Geographical regions and countries.

Additional file 4:. text file: Reported risk factors and protective factors.

Additional file 5:. text file: Risk of publication bias – funnel plots.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wichor M. Bramer for devising and executing our systematic literature search. We thank the corresponding authors of the evaluated studies for providing feedback on our extracted data.

Abbreviations

- ESBL

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

- ESBL-E

ESBL-producing Enterobacterales

- CPE

Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales

- MDR-E

Multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales

- OR

Odds ratio

- 95% CI

95% Confidence interval

- STROBE

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology guideline

- TD

Travelers’ diarrhea

- PG

Phylogenetic groups

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the study: JS, AFV, MV, AV. Collecting data: KM, AFV, BB. Analyzed the data: KM, AFV, BB. Interpretation of the data: KM, AFV, BB, JS. Drafted the work: KM, AFV, BB, JS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AFV, KM, BB, AS, AV, MV and JS declare that they have no competing interests. JS recently collaborated with employees of bioMérieux on a research project that included whole-genome sequencing of bacterial isolates, which was performed by the company.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Anne F. Voor in ‘t holt and Kees Mourik contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13756-020-00733-6.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. 2014.

- 2.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(3):268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwaber MJ, Carmeli Y. Mortality and delay in effective therapy associated with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae bacteraemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(5):913–920. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwaber MJ, Navon-Venezia S, Kaye KS, Ben-Ami R, Schwartz D, Carmeli Y. Clinical and economic impact of bacteremia with extended- spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(4):1257–1262. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1257-1262.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvanitis M, Grigoras C, Mylonakis E. Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum Beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: A systematic review and Metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):310–318. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henderson J., Ciesielczuk H., Nelson S.M., Wilks M. Community prevalence of carbapenemase-producing organisms in East London. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2019;103(2):142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly AM, Mathema B, Larson EL. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the community: a scoping review. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50(2):127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walsh TR, Weeks J, Livermore DM, Toleman MA. Dissemination of NDM-1 positive bacteria in the New Delhi environment and its implications for human health: an environmental point prevalence study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(5):355–362. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Islam MA, Islam M, Hasan R, Hossain MI, Nabi A, Rahman M, et al. Environmental spread of New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase-1-producing multidrug-resistant bacteria in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(15):1-11. PubMed PMID: 28526792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2017 Edition, : UNWTO; 2017 [cited 2018 25-03-2018]. Available from: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419029.

- 11.United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). UNWTO Tourism Highlights 2018 Edition: UNWTO; 2018 [13-01-2020]. Available from: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419876.

- 12.Tängdén T, Cars O, Melhus A, Lowdin E. Foreign travel is a major risk factor for colonization with Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a prospective study with Swedish volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(9):3564–3568. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00220-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruppé Etienne, Andremont Antoine, Armand-Lefèvre Laurence. Digestive tract colonization by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in travellers: An update. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2018;21:28–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woerther PL, Andremont A, Kantele A. Travel-acquired ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae: impact of colonization at individual and community level. J Travel Med. 2017;24(suppl_1):S29–S34. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taw101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liberati A., Altman D. G, Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gotzsche P. C, Ioannidis J. P A, Clarke M., Devereaux P J, Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339(jul21 1):b2700–b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassing RJ, Alsma J, Arcilla MS, van Genderen PJ, Stricker BH, Verbon A. International travel and acquisition of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a systematic review. Euro Surveill. 2015;20(47):1–14. PubMed PMID: 26625301. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials revisited. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;45:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy K, Collignon P. Colonisation with Escherichia coli resistant to "critically important" antibiotics: a high risk for international travellers. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(12):1501–1506. doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisenberg SA, Mediavilla JR, Chen L, Alexander EL, Rhee KY, Kreiswirth BN, et al. Extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in international travelers and non-travelers in New York City. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Östholm-Balkhed A, Tarnberg M, Nilsson M, Nilsson LE, Hanberger H, Hallgren A, et al. Travel-associated faecal colonization with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae: incidence and risk factors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(9):2144–2153. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ÖstholmBalkhed Åse, Tärnberg Maria, Nilsson Maud, Nilsson Lennart E., Hanberger Håkan, Hällgren Anita. Duration of travel-associated faecal colonisation with ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae - A one year follow-up study. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0205504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paltansing S, Vlot JA, Kraakman ME, Mesman R, Bruijning ML, Bernards AT, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among travelers from the Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(8):1206–1213. doi: 10.3201/eid.1908.130257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuenzli E, Jaeger VK, Frei R, Neumayr A, DeCrom S, Haller S, et al. High colonization rates of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in Swiss travellers to South Asia- a prospective observational multicentre cohort study looking at epidemiology, microbiology and risk factors. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:528. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Wintersdorff CJ, Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Oude Lashof AM, Hoebe CJ, Savelkoul PH, et al. High rates of antimicrobial drug resistance gene acquisition after international travel, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(4):649–657. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelin M, Forsell J, Granlund M, Evengard B, Palmgren H, Johansson A. Risk factors for colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Enterobacteriaceae in healthcare students on clinical assignment abroad: A prospective study. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2015;13(3):223–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kantele A., Laaveri T., Mero S., Vilkman K., Pakkanen S. H., Ollgren J., Antikainen J., Kirveskari J. Antimicrobials Increase Travelers' Risk of Colonization by Extended-Spectrum Betalactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;60(6):837–846. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lübbert C, Straube L, Stein C, Makarewicz O, Schubert S, Mossner J, et al. Colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in international travelers returning to Germany. Int J Med Microbiol. 2015;305(1):148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruppé Etienne, Armand-Lefèvre Laurence, Estellat Candice, Consigny Paul-Henri, El Mniai Assiya, Boussadia Yacine, Goujon Catherine, Ralaimazava Pascal, Campa Pauline, Girard Pierre-Marie, Wyplosz Benjamin, Vittecoq Daniel, Bouchaud Olivier, Le Loup Guillaume, Pialoux Gilles, Perrier Marion, Wieder Ingrid, Moussa Nabila, Esposito-Farèse Marina, Hoffmann Isabelle, Coignard Bruno, Lucet Jean-Christophe, Andremont Antoine, Matheron Sophie. High Rate of Acquisition but Short Duration of Carriage of Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae After Travel to the Tropics. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2015;61(4):593–600. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernasconi OJ, Kuenzli E, Pires J, Tinguely R, Carattoli A, Hatz C, et al. Travelers can import colistin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, including those possessing the plasmid-mediated mcr-1 gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(8):5080–5084. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00731-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizuno Y, Miura Y, Yamaguchi T, Matsumoto T. Extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae colonisation in long-term overseas business travellers. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2016;14(6):561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reuland EA, Sonder GJB, Stolte I, Al Naiemi N, Koek A, Linde GB, et al. Travel to Asia and traveller's diarrhoea with antibiotic treatment are independent risk factors for acquiring ciprofloxacin-resistant and extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae—a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22(8):731.e1–731.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vading M, Kabir MH, Kalin M, Iversen A, Wiklund S, Nauclér P, et al. Frequent acquisition of low-virulence strains of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in travellers. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(12):3548–3555. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Hattem JM, Arcilla MS, Bootsma MCJ, Van Genderen PJ, Goorhuis A, Grobusch MP, et al. Prolonged carriage and potential onward transmission of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Dutch travelers. Future Microbiol. 2016;11(7):857–864. doi: 10.2217/fmb.16.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arcilla MS, van Hattem JM, Haverkate MR, Bootsma MCJ, van Genderen PJJ, Goorhuis A, et al. Import and spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae by international travellers (COMBAT study): a prospective, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):78–85. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30319-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leangapichart T, Tissot-Dupont H, Raoult D, Memish ZA, Rolain JM, Gautret P. Risk factors for acquisition of CTX-M genes in pilgrims during Hajj 2013 and 2014. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(9):2627–2635. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peirano G, Gregson DB, Kuhn S, Vanderkooi OG, Nobrega DB, Pitout JDD. Rates of colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Canadian travellers returning from South Asia: a cross-sectional assessment. CMAJ Open. 2017;5(4):E850–E8E5. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bevan ER, McNally A, Thomas CM, Piddock LJV, Hawkey PM. Acquisition and loss of CTX-M-producing and non-producing Escherichia coli in the fecal microbiome of travelers to South Asia. mBio. 2018;9(6). 10.1128/mBio.02408-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Nakayama T, Kumeda Y, Kawahara R, Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto Y. Carriage of colistin-resistant, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli harboring the mcr-1 resistance gene after short-term international travel to Vietnam. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:391–395. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S153178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaumburg F., Sertic S.M., Correa-Martinez C., Mellmann A., Köck R., Becker K. Acquisition and colonization dynamics of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria during international travel: a prospective cohort study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2019;25(10):1287.e1-1287.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leangapichart T, Dia NM, Olaitan AO, Gautret P, Brouqui P, Rolain JM. Acquisition of extended-spectrum β-lactamases by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in gut microbiota of pilgrims during the hajj pilgrimage of 2013. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(5):3222–3226. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02396-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leangapichart Thongpan, Gautret Philippe, Griffiths Karolina, Belhouchat Khadidja, Memish Ziad, Raoult Didier, Rolain Jean-Marc. Acquisition of a High Diversity of Bacteria during the Hajj Pilgrimage, Including Acinetobacter baumannii withblaOXA-72and Escherichia coli withblaNDM-5Carbapenemase Genes. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2016;60(10):5942–5948. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00669-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jans B, Huang TD, Bauraing C, Berhin C, Bogaerts P, Deplano A, et al. Infection due to travel-related carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, a largely underestimated phenomenon in Belgium. Acta Clin Belg. 2015;70(3):181–187. doi: 10.1179/2295333715Y.0000000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.World Health Organization. International travel and health 2012.

- 47.Kantele Anu, Mero Sointu, Kirveskari Juha, Lääveri Tinja. Increased Risk for ESBL-Producing Bacteria from Co-administration of Loperamide and Antimicrobial Drugs for Travelers’ Diarrhea1. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2016;22(1):117–120. doi: 10.3201/eid2201.151272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kantele Anu, Mero Sointu, Kirveskari Juha, Lääveri Tinja. Fluoroquinolone antibiotic users select fluoroquinolone-resistant ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (ESBL-PE) – Data of a prospective traveller study. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2017;16:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keystone JS, Connor BA. Antibiotic self-treatment of travelers' diarrhea: it only gets worse! Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017;16:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lääveri T, Pakkanen SH, Kirveskari J, Kantele A. Travellers' diarrhoea: impact of TD definition and control group design on study results. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2018; PubMed PMID: 29409749. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Food and Water Safety: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013 [updated 08–01-2018; cited 2018 24-04-2018]. Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/food-water-safety.

- 52.Steffen Robert, Hill David R., DuPont Herbert L. Traveler’s Diarrhea. JAMA. 2015;313(1):71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shlim DR. Looking for evidence that personal hygiene precautions prevent traveler's diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 8):S531–S535. doi: 10.1086/432947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kluytmans-van den Bergh MFQ, van Mens SP, Haverkate MR, Bootsma MCJ, Kluytmans J, Bonten MJM, et al. Quantifying hospital-acquired carriage of extended-Spectrum Beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among patients in Dutch hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2018;39(1):32–39. doi: 10.1017/ice.2017.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogers BA, Kennedy KJ, Sidjabat HE, Jones M, Collignon P, Paterson DL. Prolonged carriage of resistant E. coli by returned travellers: clonality, risk factors and bacterial characteristics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31(9):2413–2420. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1584-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1:. text file: The PRISMA Checklist.

Additional file 2:. text file: Literature search strategy – list of search terms.

Additional file 3:. text file: Geographical regions and countries.

Additional file 4:. text file: Reported risk factors and protective factors.

Additional file 5:. text file: Risk of publication bias – funnel plots.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.