Abstract

Histamine binds to one of the four G-protein–coupled receptors expressed by large cholangiocytes and increases large cholangiocyte proliferation via histamine-2 receptor (H2HR), which is increased in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Ranitidine decreases liver damage in Mdr2−/− (ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 4 null) mice. We targeted hepatic H2HR in Mdr2−/− mice using vivo-morpholino. Wild-type and Mdr2−/− mice were treated with mismatch or H2HR vivo-morpholino by tail vein injection for 1 week. Liver damage, mast cell (MC) activation, biliary H2HR, and histamine serum levels were studied. MC markers were determined by quantitative real-time PCR for chymase and c-kit. Intrahepatic biliary mass was detected by cytokeratin-19 and F4/80 to evaluate inflammation. Biliary senescence was determined by immunofluorescence and senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining. Hepatic fibrosis was evaluated by staining for desmin, Sirius Red/Fast Green, and vimentin. Immunofluorescence for transforming growth factor-β1, vascular endothelial growth factor-A/C, and cAMP/ERK expression was performed. Transforming growth factor-β1 and vascular endothelial growth factor-A secretion was measured in serum and/or cholangiocyte supernatant. Treatment with H2HR vivo-morpholino in Mdr2−/−–mice decreased hepatic damage; H2HR protein expression and MC presence or activation; large intrahepatic bile duct mass, inflammation and senescence; and fibrosis, angiogenesis, and cAMP/phospho-ERK expression. Inhibition of H2HR signaling ameliorates large ductal PSC-induced damage. The H2HR axis may be targeted in treating PSC.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is characterized by inflammation of bile ducts and is most commonly seen in large bile ducts.1,2 Large bile ducts (>15 μmol/L) are lined by large cholangiocytes that express secretin receptor and regulate proliferation via protein kinase A (PKA)/cAMP/ERK1/2 signaling.3, 4, 5 Along with inflammation, during PSC there is remarkable ductular reaction that is marked by cholangiocyte proliferation.6, 7, 8 On proliferation, cholangiocytes take on a neuroendocrine phenotype that contributes to activation of other cells, including Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). HSCs are the prime driver of hepatic fibrosis, and recent work has found that cholangiocytes and HSCs work together during PSC progression.9,10 The current treatment paradigm for patients with PSC is very limited and inconsistent. There is a subpopulation of patients with PSC who respond to ursodeoxycholic acid; however, no reliable therapy is available in most cases.11,12 The mechanisms that drive PSC progression are currently being studied by a number of research groups, but the status quo of the disease remains unchanged. Thus, there is a great need for novel treatment strategies.

Numerous studies have found that histamine and histamine receptors (HRs) regulate ductular reaction and hepatic fibrosis.9,13, 14, 15, 16 Furthermore, histamine levels and histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) gene expression are increased in patients with PSC and in the PSC rodent model, multidrug-resistant gene knockout, which is deficient in ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 4 (Abcb4−/− alias Mdr2−/−) mice.9 Recently, treatment with an over-the-counter drug, ranitidine (H2HR blocker), decreased biliary damage and hepatic fibrosis in Mdr2−/− mice. Furthermore, pharmaceutical inhibition of H2HR specifically targeted large cholangiocytes.9 In healthy rats, treatment with histamine increased large intrahepatic biliary mass (IBDM) via cAMP/PKA/ERK1/2 signaling, and in vitro studies found that inhibition of H2HR blocked histamine-induced proliferation.16 The prime source for circulating histamine is mast cells (MCs), which are immune cells derived from bone marrow. On migration to desired tissue or organ, MCs will mature and degranulate when activated.17,18 The largest mediator released from MCs is histamine, and activation of HRs can induce degranulation of MCs. Previous studies have found that MCs infiltrate the damaged liver and are found surrounding large bile ducts in Mdr2−/− mice, in human PSC, and during cholestatic liver injury.9,19 Inhibition of MC migration and/or degranulation decreases biliary damage and hepatic fibrosis in multiple models of liver injury.9,20,21

Besides ductular reaction, inflammation, and hepatic fibrosis, angiogenesis may also be a key mediator of PSC progression. Cholangiocytes and MCs are known to participate in angiogenesis during PSC and cholangiocarcinoma9,19,20; however, information on HR-mediated angiogenesis is lacking. Histamine stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling after bile duct ligation (BDL), and when l-histidine-decarboxylase knockout mice are subjected to BDL, VEGF secretion and expression are decreased, thus demonstrating that histamine may be involved in tissue angiogenesis.22,23 In MC-deficient mice (Kitw-sh) subjected to BDL, there is decreased von Willebrand factor and VEGF signaling when compared with BDL wild-type (WT) mice.19 Finally, tumor growth and angiogenesis were blunted when nu/nu mice were treated with the H2HR antagonist ranitidine, suggesting that HRs may mediate angiogenesis.9

In follow-up to previous work using ranitidine,9 this investigation performed studies using a liver-specific delivery of H2HR vivo-morpholino to block this receptor and downstream signaling during PSC progression in Mdr2−/− mice. The studies aimed to demonstrate that blocking H2HR decreases large biliary damage and hepatic inflammation, fibrosis, and angiogenesis.

Methods and Materials

Reagents and Other Materials

Chemical grade reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO) unless stated otherwise. Total RNA was isolated by the TRI Reagent from Sigma Life Science (St. Louis, MO) and reverse transcribed with the Reaction Ready First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).9,24 For staining in liver sections, samples were sectioned at 4 to 6 μm, and 10 fields were analyzed from 3 samples from at least 4 animals per group.

In Vivo Models

For animal studies, the multidrug-resistant, genetically modified mouse model of PSC [Mdr2−/− mice raised on FVB/NJ background (WT)] was used.21,25 Mdr2−/− mice present with biliary damage, hepatic fibrosis, and inflammation as early as a few weeks of age; however, the most common time point studied is 12 weeks of age.2,21,25 Male WT and male Mdr2−/− mice were treated with mismatch morpholino (5′-TAAACCATGCAATTGGACTCAATTC-3′) or an H2HR vivo-morpholino (5′-TGAACCGTGCCATTGGGCTCCATTC-3′) given by tail vein injection 2 times per week for 1 week (4 μg/100 μL sodium chloride) per previous work.26,27 Mice (8 to 10 mice per group) were euthanized at 12 weeks of age.12,21 From these groups, liver blocks (frozen and paraffin-embedded), serum, isolated cholangiocytes, and cholangiocyte supernatants (1 million cells per 100 μL) were collected as previously described.21,24

Morphologic and Chemical Analysis of Liver Damage in Mdr2−/− Mice

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed in livers from WT and Mdr2−/− mice that were treated with mismatch or H2HR vivo-morpholino to evaluate lobular damage, necrosis, and inflammation. Serum levels of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and γ-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT) were measured in all groups of mice using IDEXX Catalyst One test slides (IDEXX, Westbrook, ME).9,21

Evaluation of H2HR Protein Expression, Histamine Secretion, and MC Infiltration and Activation

To demonstrate that H2HR expression was inhibited using vivo-morpholino, immunohistochemistry was performed for H2HR in all liver sections. Histamine secretion was evaluated by enzyme immunoassay in serum from all groups of mice.19, 20, 21 The presence of MCs was evaluated by immunohistochemistry for mouse MC protease-1 in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch and H2HR vivo-morpholino.19,28 The presence of MCs was not measured in WT groups because it has been previously reported that WT mice display few, if any, hepatic MCs.9,20,28 MC marker (chymase and c-Kit) mRNA expression was determined in total liver by quantitative real-time PCR (ΔΔCT fold change29,30) in WT and Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR mismatch along with Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino.

Measurement of Ductular Reaction, Proliferation, Inflammation, and Biliary Senescence

Because stimulation of H2HR enhances large, but not small, IBDM,16 changes in small and large IBDM and proliferation were measured in WT and Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch or H2HR vivo-morpholino. Immunohistochemistry was performed for proliferating cell nuclear antigen to detect proliferating small and large cholangiocyte populations, and cytokeratin (CK)-19 staining was used to evaluate alterations in small and large IBDMs.16,19,21 To determine changes in inflammation, liver sections from WT and Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch or vivo-morpholino were stained for F4/80 to mark Kupffer cells as previously demonstrated.9 F4/80 staining was semiquantified using Visiopharm version VIS 6.7.0.2590 (Visiopharm, Hoersholm, Denmark).

Biliary senescence is also a feature of PSC and is up-regulated in Mdr2−/− mice.31,32 Biliary senescence was measured in all groups of mice by immunofluorescence for p16 (co-stained with CK-19) as described previously and by senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining in Mdr2−/− groups.32

Evaluation of HSC Activation and Hepatic Fibrosis

To determine whether blocking H2HR signaling alters HSC activation, the expression of desmin (co-stained with CK-19) was measured by immunofluorescence19,21 in all groups of mice. All groups of mice were evaluated for liver fibrosis by staining for Fast Green/Sirius Red (and semiquantification).19,21 In addition, the expression of vimentin (mesenchymal marker) and the epithelial markers CK-18 and E-cadherin was determined by immunohistochemistry in all groups of mice.32 Finally, because transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 plays a critical role in PSC progression, HSC activation, and hepatic fibrosis, the expression of TGF-β1 was evaluated by immunofluorescence (co-stained with CK-19) and serum levels of TGF-β1 from all groups of mice by enzyme immunoassay.19,21

Evaluation of VEGF Signaling and Angiogenesis

Because histamine regulates biliary damage via VEGF signaling,22,23 the effects of inhibition of H2HR on this pathway were measured. In all groups of mice, VEGF-A/C and von Willebrand factor (vWF) expression was determined by immunofluorescence (co-stained with CK-19 to mark bile ducts). VEGF secretion was determined in cholangiocyte supernatant and serum from all groups of mice by enzyme immunoassay.22,23

Determination of Intracellular Signaling

Previous work has found that H2HR signaling occurs primarily through activation of Gαs/cAMP/PKA/ERK16; therefore, this signaling pathway was evaluated in all groups of mice. cAMP levels and ERK1/2 expression were determined by immunofluorescence in liver sections (co-stained with CK-19 to mark cholangiocytes).

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Groups were analyzed by the unpaired t-test when two groups are analyzed or a two-way analysis of variance when more than two groups are analyzed, followed by an appropriate post hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

H2HR Vivo-Morpholino Treatment Ameliorates Hepatic Damage, Inflammation, and Necrosis in Mdr2−/− Mice but Has No Deleterious Effects on WT Mice

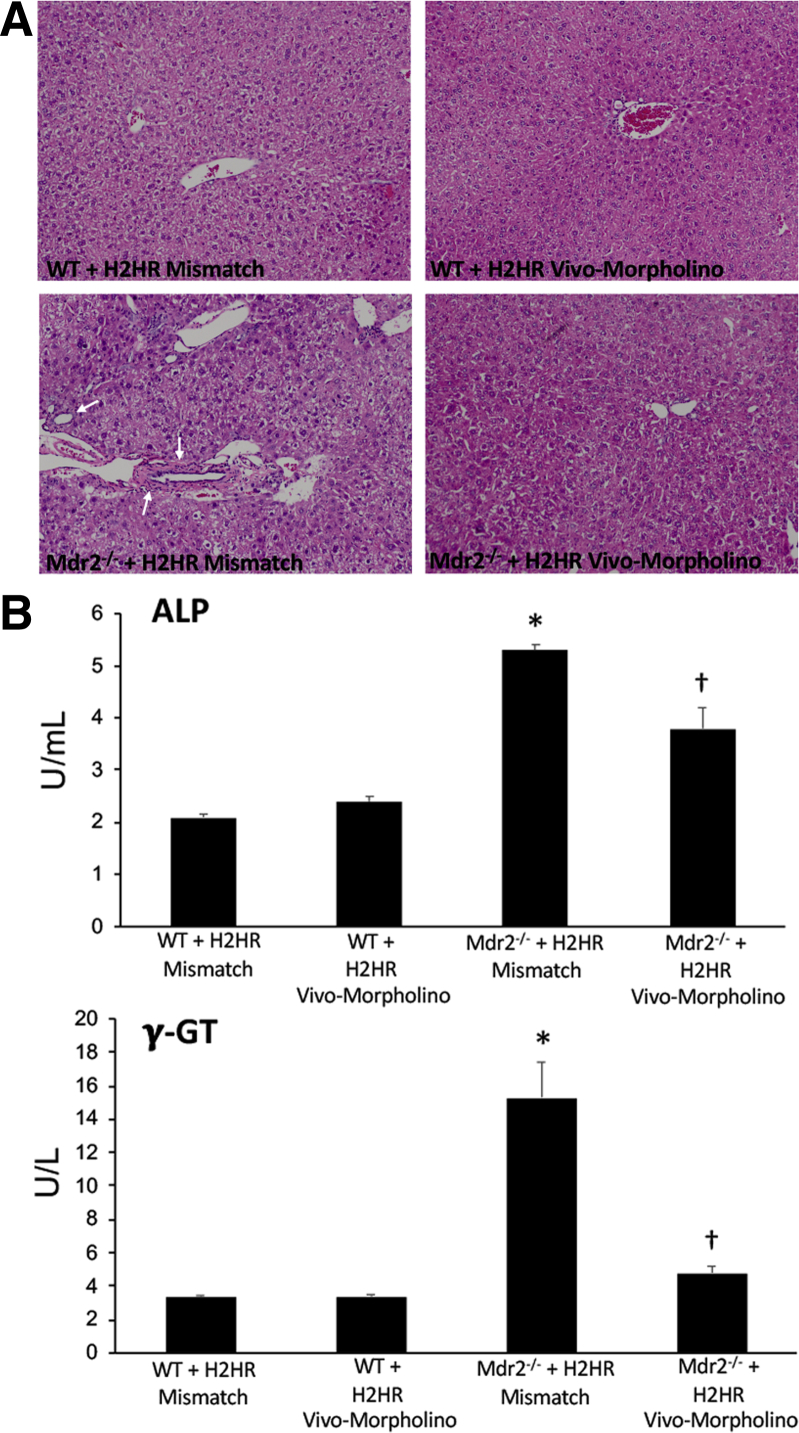

By H&E staining (Figure 1A), WT mice treated with mismatch or H2HR vivo-morpholinos had no alterations in hepatic morphologic findings. Furthermore, inflammation and necrosis were visibly reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino compared with Mdr2−/− H2HR mismatch mice that had typical PSC damage. Similarly, in Figure 1B, no changes were observed between WT groups for serum chemistry; however, Mdr2−/− H2HR mismatch mice had increased levels of ALP and γ-GT, markers of cholangiocyte damage. Blocking H2HR by vivo-morpholino down-regulated serum levels of ALP and γ-GT compared with mismatch Mdr2−/− mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Pathologic alterations after vivo-morpholino treatment. A and B: Pathologic changes were evaluated in all livers by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining (A) and in serum for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and γ-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT) levels (B). A: H&E staining reveals no changes between wild-type (WT) groups treated with mismatch or histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino, whereas Mdr2−/− (ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 4 null) mice treated with H2HR mismatch display areas of lobular damage, inflammation, and necrosis (white arrows). There is no hepatic damage in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. B: Serum levels of ALP (top panel) and γ-GT (bottom panel) remain unchanged in WT groups; however, both markers are increased in serum from Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR mismatch. ALP and γ-GT serum levels decrease in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 12 experiments for IDEXX. ∗P < 0.05 versus WT mismatch; †P < 0.05 versus Mdr2−/− mice + H2HR vivo-morpholino. Original magnification, ×20 (A).

Treatment with H2HR Vivo-Morpholino Decreases Histamine Levels, Biliary H2HR Expression, and MC Infiltration in Mdr2−/− Mice

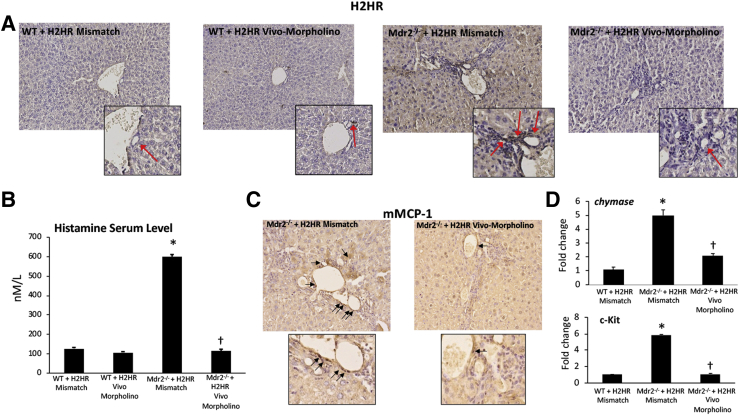

Biliary H2HR protein expression increased in Mdr2−/− mismatch liver shown by immunohistochemistry (Figure 2A) compared with WT H2HR mismatch treated mice. No H2HR expression was found in WT or Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Evaluation of histamine-2 receptor (H2HR)/histamine signaling and mast cell (MC) presence. A: There is little expression of H2HR in wild-type (WT) groups as shown by immunohistochemistry; however, multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout [Mdr2−/− (ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 4 null)] mice treated with mismatch have increased biliary H2HR expression (primarily in large cholangiocytes; red arrows) that is lost in mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. In Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch, there is an increase in histamine serum levels (B) and MC presence (C; black arrows); however, Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino have decreased histamine secretion and fewer MCs. D: MC marker expression, chymase, and c-Kit were determined by quantitative real-time PCR, and there is an increase in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H1HR mismatch compared with WT mice, whereas expression is decreased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. No differences were found between WT groups (data not shown). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 16 experiments for enzyme immunoassay (EIA); n = 12 experiments for real-time PCR. ∗P < 0.05 versus WT mismatch; †P < 0.05 versus Mdr2−/− mice + H2HR vivo-morpholino. Original magnification: ×40 (A and C, main images); ×100 (A and C, insets). mMCP-1, mouse MC protease-1.

Histamine serum levels significantly increased when Mdr2−/− mice were treated with mismatch morpholino compared with WT mismatch mice. Treatment with H2HR vivo-morpholino decreased histamine secretion in Mdr2−/− mice compared with mismatch treatment; there were no significant changes in the WT groups (Figure 2B).

MC infiltration was up-regulated in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch morpholinos (similar to previous studies reporting an increased in Mdr2−/− mice9,21) as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry for mouse MC protease-1 but were reduced in Mdr2−/− H2HR vivo-morpholino mice (Figure 2C). The mRNA expression of chymase and c-Kit increased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR mismatch compared with WT, whereas expression was decreased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (Figure 2D). There was no significant difference between WT mice treated with mismatch or H2HR vivo-morpholino (data not shown); therefore, only WT mismatch samples were used for analysis.

Treatment with H2HR Vivo-Morpholino Reduces Large but Not Small Bile Duct Growth, Inflammation, and Large Biliary Senescence in Mdr2−/− Mice

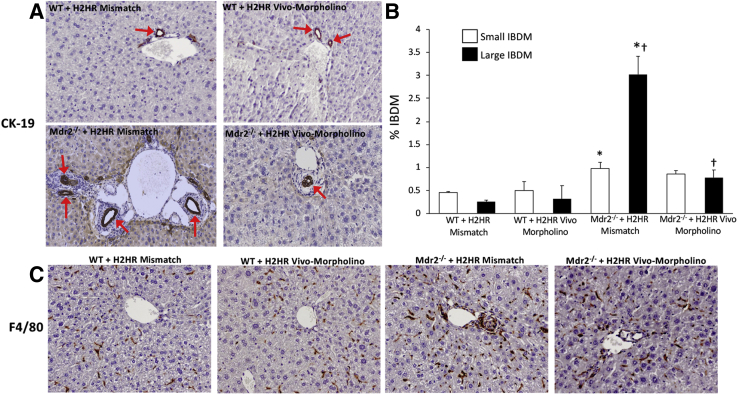

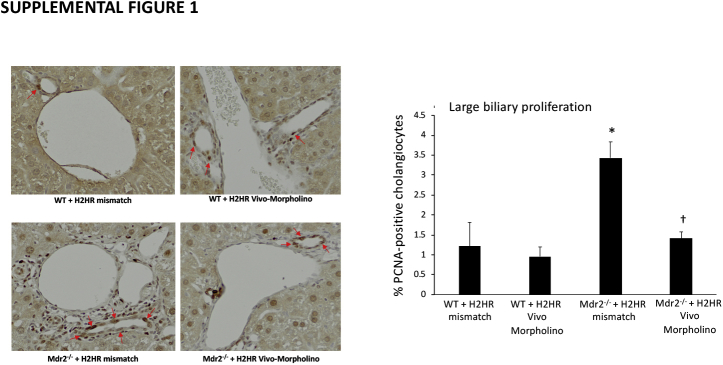

In Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino, there was a significant decrease in large IBDM (Figure 3A) compared with Mdr2−/− mismatch; however, small IBDM did not significantly change in the Mdr2−/− groups (Figure 3B). Biliary proliferation in large cholangiocytes in Mdr2−/− mismatch mice was significantly decreased after H2HR vivo-morpholino treatment (Supplemental Figure S1). Small proliferation was not changed in Mdr2−/− groups (data not shown). No changes were seen in small or large IBDMs or proliferation in WT groups.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of small and large intrahepatic bile duct mass (IBDM) and inflammation. A and B: With the use of cytokeratin (CK)-19 immunohistochemistry, no changes are observed between wild-type (WT) groups with regard to small and large IBDM; however, in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch, there is a significant increase in small and large IBDM (with large IBDM being significantly greater than small IBDM) compared with WT groups. Furthermore, when Mdr2−/− mice were treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino, only large IBDM are significantly reduced (no significant changes are seen in small IBDM). Representative images (red arrows mark CK-19–positive bile ducts) (A) and semiquantification (B) are provided for all groups. C: Hepatic inflammation was determined by immunohistochemistry for F4/80 (Kupffer cell marker). The presence of Kupffer cells remains unchanged in WT groups versus Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch (WT H2HR mismatch = 5.065 ± 0.624; WT H2HR vivo-morpholino = 5.089 ± 0.946; Mdr2−/− H2HR mismatch = 4.904 ± 0.636). There is a reduction in mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (3.182 ± 0.835); however, it is not significant when compared with Mdr2−/− mismatch. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 10 representative images; n = 6 mice for each group. ∗P < 0.05 versus small and large IBDM from WT mismatch; †P < 0.05 versus large IBDM from Mdr2−/− + H2HR mismatch. Original magnification, ×40 (A and C).

The presence of Kupffer cells (marked by F4/80 immunohistochemistry and semiquantified using Visiopharm software) was unchanged in the WT groups versus Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch (WT H2HR mismatch = 5.065 ± 0.624; WT H2HR vivo-morpholino = 5.089 ± 0.946; Mdr2−/− H2HR mismatch = 4.904 ± 0.636). There was a reduction in mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (3.182 ± 0.835); however, this finding was not significant when compared with Mdr2−/− mismatch (Figure 3C).

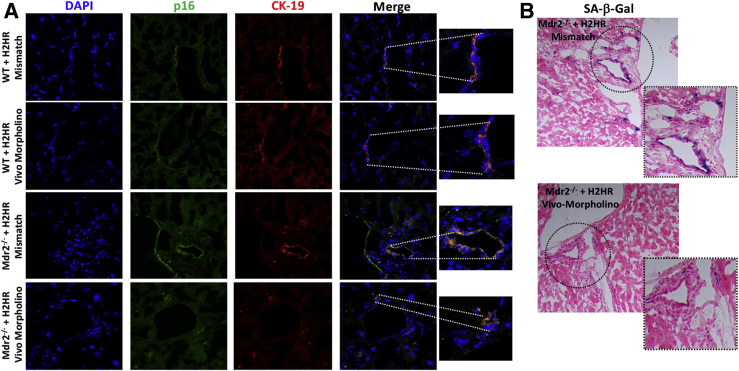

The expression of p16 was increased in large bile ducts from Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch compared with WT controls; however, inhibition of H2HR decreased large duct p16 expression as shown by immunofluorescence (Figure 4A). Staining for SA-β-gal (Figure 4B) resulted in a number of large senescent cholangiocytes in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR mismatch; however, no large senescent cholangiocytes were found in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino; there was no positive SA-β-gal staining found in WT groups (data not shown). There were no significant changes in WT groups for biliary proliferation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of biliary senescence. Biliary senescence was determined by immunofluorescence for p16 [co-stained with cytokeratin (CK)-19 to mark bile ducts] and senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining in liver sections. A: Immunofluorescence shows an increase in co-localization of p16/CK-19 in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch in large cholangiocytes (lining a large bile duct), whereas no large senescent bile ducts are noted in Mdr2−/− mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino. No changes in co-localization are seen in wild-type (WT) groups. B: SA-β-gal staining shows a number of large senescent cholangiocytes in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch that is absent in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. No changes in SA-β-gal staining are noted between WT groups (data not shown). Original magnification: ×40 (A and B, main images); ×100 (A and B, higher magnifications).

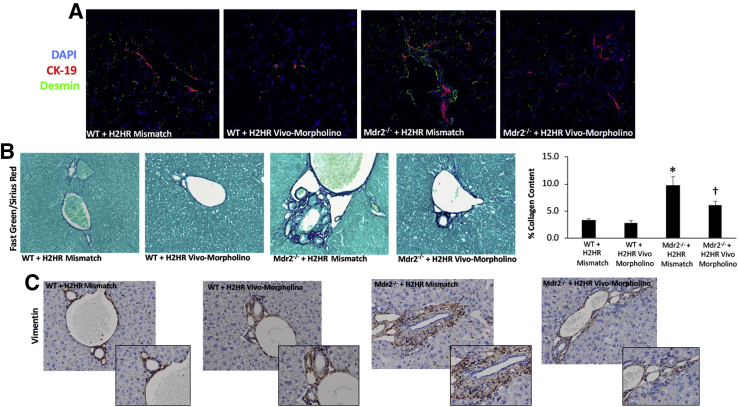

HSC Activation, Fibrosis, and TGF-β1 Are Decreased in Mdr2−/− Mice Treated with H2HR Vivo-Morpholino Compared with Mdr2−/− Mismatch Treatment

HSC activation increased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR mismatch, which was subsequently decreased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino as shown by immunofluorescence desmin (Figure 5A). In addition, collagen deposition shown by Fast Green/Sirius Red and semiquantification was reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino compared with Mdr2−/− H2HR mismatch mice, which was up-regulated compared with WT H2HR mismatch (Figure 5B). No alterations in HSC activation or hepatic fibrosis were noted in WT mismatch mice versus WT mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (Figure 5, A and B).

Figure 5.

Determination of hepatic fibrosis and hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation. HSC activation was determined by immunofluorescence for desmin [co-stained with cytokeratin (CK)-19 to mark bile ducts] and hepatic fibrosis by staining for Fast Green/Sirius Red (and semiquantification) and immunohistochemistry for vimentin. A: The intensity of desmin increases in Mdr2−/− (ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 4 null) mice treated with mismatch compared with wild-type (WT) mismatch; however, Mdr2−/− mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino have a reduction in desmin staining. B: Similar trends are seen for Fast Green/Sirius Red staining that displays significantly increased amounts of collagen deposition around the portal area in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch compared with WT mismatch. Mdr2−/− mice that were treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino have less collagen deposition. Fast Green/Sirius Red is also shown semiquantified. C: Vimentin staining reveals a number of vimentin-positive cells surrounding the portal area in WT groups that is increased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch; however, there are fewer vimentin-positive cells in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. ∗P < 0.05 versus WT mismatch; †P < 0.05 versus Mdr2−/− + H2HR mismatch. Original magnification: ×40 (A–C); ×80 (C, insets).

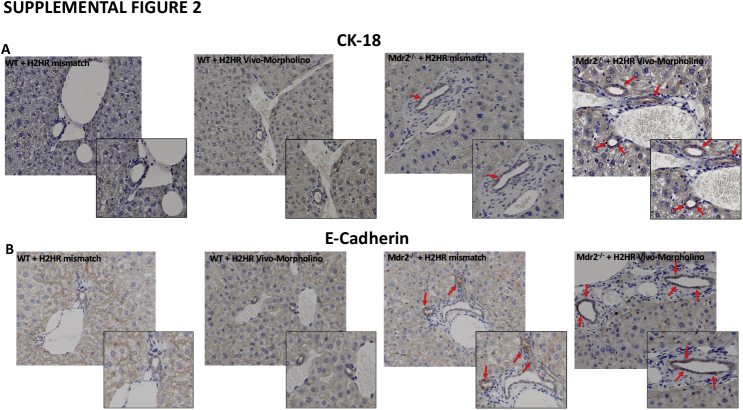

The expression of vimentin was up-regulated in Mdr2−/− H2HR mismatch and was found to be strongly expressed in the portal area but not by cholangiocytes. In Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino, the expression of vimentin was decreased compared with mismatch (Figure 5C), and no changes were observed between WT groups. Because a change in vimentin expression was observed, the epithelial markers CK-18 and E-cadherin were also measured by immunohistochemistry. Both CK-18 and E-cadherin were up-regulated in large cholangiocytes from Mdr2−/− H2HR vivo-morpholino mice compared with Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR mismatch (Supplemental Figure S2). No changes were noted between the WT groups.

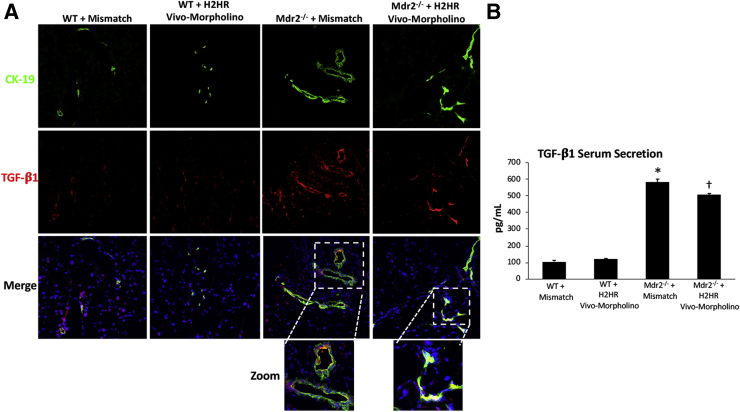

A hallmark feature of increased hepatic fibrosis is elevated TGF-β1 expression and secretion. Immunofluorescence in liver sections showed that biliary TGF-β1 expression increased in Mdr2−/− mismatch mice compared with WT mismatch, which was decreased in Mdr2−/− mice treated with the H2HR vivo-morpholino (Figure 6A). In addition, serum levels of TGF-β1 increased in Mdr2−/− mismatch mice, which was significantly reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (Figure 6B). Again, no changes were observed in TGF-β1 expression or secretion in WT mismatch or H2HR vivo-morpholino mice.

Figure 6.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 expression and secretion. The expression and secretion of TGF-β1 were measured in all groups of mice. A: Immunofluorescence shows co-localization of cytokeratin (CK)-19 (to mark bile ducts) and TGF-β1 in large cholangiocytes in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch compared with wild-type (WT) mismatch mice, whereas Mdr2−/− mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino have little co-localization. B: Serum secretion of TGF-β1 does not change between WT groups; however, Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch have increased levels of TGF-β1, which were decreased in mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. ∗P < 0.05 versus WT mismatch; †P < 0.05 versus Mdr2−/− + H2HR mismatch. Original magnification: ×40 (main images); ×80 (higher magnifications).

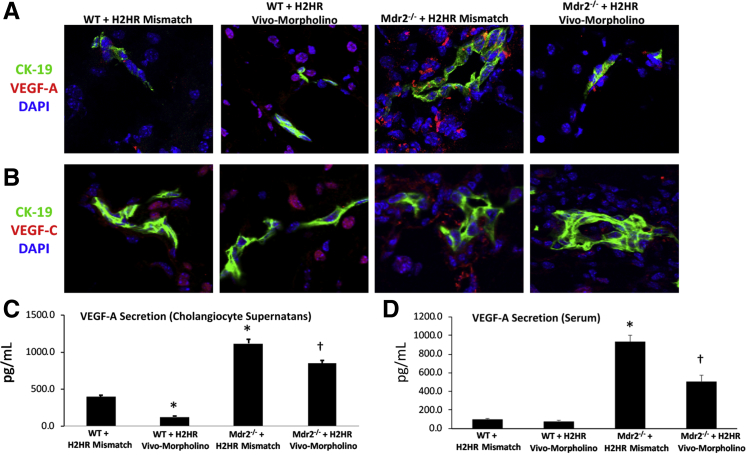

Inhibition of H2HR by Vivo-Morpholino Decreases Large Cholangiocyte VEGF-A/C Expression and Secretion and Angiogenesis

By immunofluorescence, WT mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino had less biliary expression of VEGF-A (VEGF-C expression was similar in WT groups); however, hepatocyte VEGF-A and VEGF-C are present in WT mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. VEGF-A/C biliary expression increased in Mdr2−/− mismatch mice compared with WT groups that was reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino (Figure 7, A and B). VEGF-A secretion was evaluated in large cholangiocyte supernatant and in serum from all animal groups. In WT mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino, there was a significant decrease in biliary VEGF-A secretion, whereas serum levels between WT groups remained similar (Figure 7, C and D). In Mdr2−/− mismatch mice there was an increase in cholangiocytes supernatant and serum VEGF-A levels, which was decreased in supernatant (Figure 7C) and serum (Figure 7D) from Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino.

Figure 7.

Evaluation of angiogenesis. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and -C expression was determined by immunofluorescence in all groups of mice, and VEGF-A levels were measured in large cholangiocyte supernatant and serum. Wild-type (WT) mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino have less biliary expression of VEGF-A (VEGF-C expression was similar in WT groups), and VEGF-A (A) and VEGF-C (B) expression increases in large bile ducts [stained with cytokeratin (CK)-19] from multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch that is reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. Cholangiocyte supernatant (C) and serum secretion of VEGF-A (D) increase in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch that is significantly reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. No changes are seen in the WT groups. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 9experiments for enzyme immunoassay. ∗P < 0.05 versus WT mismatch; †P < 0.05 versus Mdr2−/− mice + H2HR vivo-morpholino. Original magnification, ×40 (A and B).

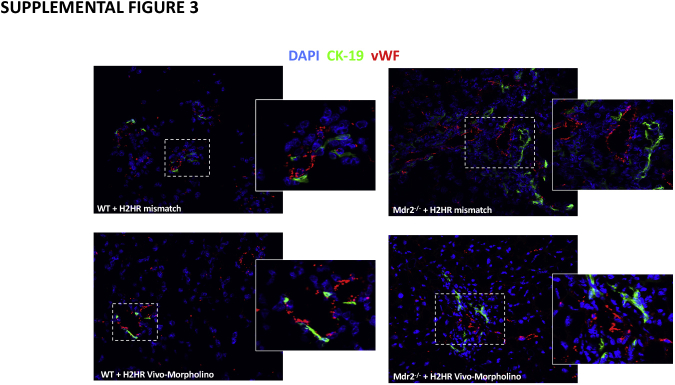

In Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch, there was an increase in the intensity of vWF expression primarily around large bile ducts; however, after H2HR vivo-morpholino treatment, vWF presence was reduced as shown by immunofluorescence and co-stained with CK-19 to mark bile ducts (Supplemental Figure S3) No changes were noted between WT mismatch and WT H2HR vivo-morpholino treatment. These data support our previous work demonstrating that histamine and its receptors regulate angiogenesis and VEGF signaling.20,23,24

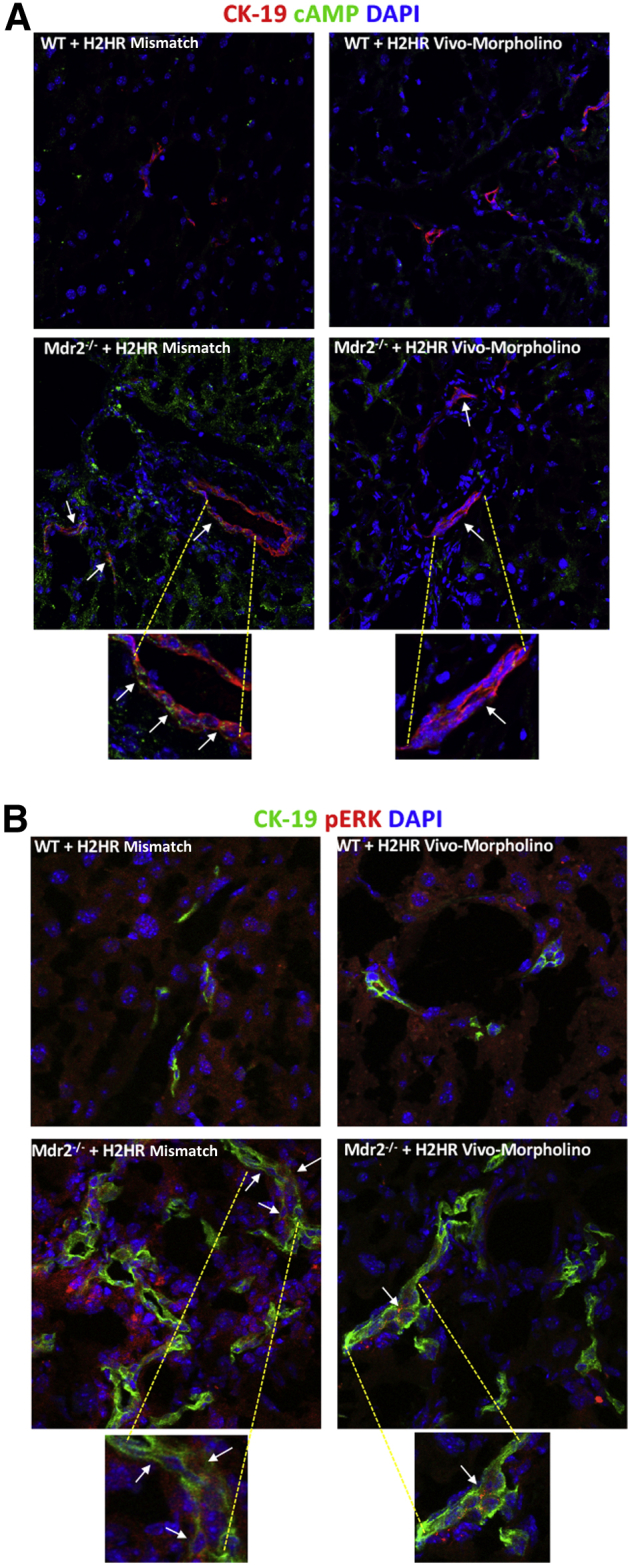

Inhibition of H2HR Decreases Large Biliary cAMP and ERK Signaling in Mdr2−/− Mice

Lastly, in Figure 8, large bile ducts have increased expression of cAMP (Figure 8A) and ERK (Figure 8B) in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch when compared with WT groups (no difference between mismatch or vivo-morpholino treatment) that was reduced when Mdr2−/− mice were treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino as shown by immunofluorescence. Both cAMP and ERK were co-stained with CK-19 to identify large bile ducts.

Figure 8.

Determination of intracellular cAMP/ERK signaling. cAMP and ERK expression was evaluated by immunofluorescence [co-stained with cytokeratin (CK)-19 to mark bile ducts). Both cAMP (A) and phospho-ERK (B) expression and co-localization increase in large bile ducts (arrows) in Mdr2−/− (ATP binding cassette subfamily B member 4 null) mice treated with mismatch, which is reduced in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with H2HR vivo-morpholino. There are no changes between wild-type (WT) groups. Original magnification: ×40 (A, top row); ×80 (A, bottom row, and B); ×100 (A and B, enlargements).

Discussion

PSC is associated with large duct damage, and patients with PSC are also at a higher risk for developing large ductal CCA; therefore, the investigation of mechanisms regulating large duct damage are clinically warranted. This study found that, using the vivo-morpholino technique to inhibit H2HR (primarily expressed in MCs and cholangiocytes), there was significant amelioration of biliary damage, hepatic fibrosis, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Inhibition of H2HR was regulated through cAMP/ERK1/2 signaling and also altered biliary senescence. These parameters are features of PSC progression and are mimicked in the Mdr2−/− mouse model.2,25

Histamine is a profibrogenic and protumorigenic molecule that is contained primarily in the granules of MCs, which migrate as immature immune cells from the bone marrow into the targeted tissue or organ. Histamine regulates its effects via one of four G-protein–coupled receptors (H1HR to H4HR), and H1HR and H2HR are primarily stimulatory receptors that induce cell proliferation and regeneration,33 whereas H3HR and H4HR are inhibitory receptors, which typically block cellular growth or tumorigenesis.13,30 It was previously noted that there is an increase in hepatic immunostaining for H1HR and H2HR in both Mdr2−/− mice and human PSC compared with their respective controls.9,21 Furthermore, in the Mdr2−/− mice, H2HR expression was more strongly increased than H1HR and was predominantly found within large bile ducts.9 In a separate study, hepatic mRNA expression of H1HR to H4HR increased in Mdr2−/− mice and human PSC compared with their respective controls.34 It has been previously demonstrated that blocking H2HR using a pharmacologic compound, ranitidine, decreases biliary damage, hepatic fibrosis, and inflammation.9 Vivo-morpholino delivery inhibits the protein expression of H2HR in the liver, specifically in cholangiocytes because H2HR is primarily found in large bile duct cells.9,16 To support this finding, other studies have reported that treatment with vivo-morpholino oligos reduces the expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone26 and miR-2435 in the liver and, subsequently, decreased biliary damage. Vivo-morpholino delivery did not have any deleterious effects in WT mice as shown by H&E and serum chemistry; however, in Mdr2−/− mice, the inhibition of H2HR decreased necrosis and inflammation. These findings are consistent with previous work using vivo-morpholino delivery.26,35 Considering that H1HR and H2HR stimulate proliferation, with H3HR and H4HR inhibiting it, it is unclear why all four receptors are up-regulated during PSC. Because histamine levels are up-regulated in patients with PSC,34 there may be an increase in HR activity to compensate for increased histamine circulation; however, further work to evaluate the specific cell types expressing each receptor is required to understand the role of HR expression and histamine signaling during PSC pathogenesis.

Because previous work has found that Mdr2−/− mice have increased MC infiltration and histamine levels,9,21 these parameters were measured in the current study. This study found that inhibition of H2HR decreased both MC presence and histamine serum levels, which is also evidence that HRs can regulate MCs and histamine release. In support of this finding, genetic knockdown of H2HR has been found to decrease histamine-induced anaphylaxis; however, when both H1HR and H2HR were knocked down, the effect of histamine was almost ablated.36 Furthermore, a study that measured histamine output after exercise found that interstitial tryptase and histamine levels increased after exercise; however, this effect was blunted when H1HR or H2HR were inhibited,37 supporting the concept that MC degranulation can be regulated by HRs.

Ductular reaction is defined by the proliferation of reactive bile ducts after liver injury. Biliary hyperplasia is also used to describe the reaction of the biliary tree after insult and can include an increase in the number of functioning ducts along with excessive fibrosis.8 Mdr2−/− mice mimic ductular reaction and therefore can be a useful tool to study pathologic changes and signaling mechanisms. This study found that there is an increase in large ductal mass and biliary proliferation that was also coupled with an increased in senescent large bile ducts in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch compared with WT groups. Because PSC is primarily a disease of large ducts,2,11 these findings of a reduction in large ductular reaction after inhibition of H2HR may be clinically relevant. Intracellular signaling pathways regulate cellular response, which may be proliferation or apoptosis. Because it has been previously reported that H2HR signals primarily through cAMP/pERK pathways9,16 to decrease proliferation, our study measured these signals and found that inhibition of H2HR reduced the expression of both cAMP and pERK, specifically in large cholangiocytes. In support of these findings, in Leydig tumor cells, H2HR expression is up-regulated coupled with increased levels of cAMP and ERK phosphorylation.38

Biliary senescence increases in PSC (human and rodent models), and blocking a specific senescence-associated secretory phenotype factor, stem cell factor, using vivo-morpholino decreases PSC pathology and progression in Mdr2−/− mice.29 A study by Moncsek et al31 found that inhibition of extralarge B-cell lymphoma reduced hepatic fibrosis by acting on senescent cholangiocytes. The extralarge B-cell lymphoma inhibitor decreased the survival and increased apoptosis in senescent cholangiocytes in Mdr2−/− mice, thus demonstrating a role for targeting senescence during PSC.31

Portal fibrosis and mesenchymal vimentin expression were also increased around large bile ducts in Mdr2−/− mice treated with mismatch compared with WT groups, which was reduced when H2HR was blocked with vivo-morpholino. In support of this, studies have confirmed that Mdr2−/− mice present with increased fibrosis at approximately 8 to 12 weeks of age,1,21,32 and a recent study that targeted vimentin using vivo-morpholino found that inhibition of vimentin decreased PSC progression in Mdr2−/− mice.32 Interestingly, the study by Zhou et al32 also found that blocking vimentin decrease biliary senescence, thus demonstrating an alternative avenue for regulating senescence during PSC.

TGF-β1 has been widely studied during fibrosis progression, and this growth factor has also been implicated in promoting cellular senescence and may also have a role in regulating epithelial-mesenchymal phenotypes during disease progression. The cellular senescence-inhibited gene, when activated, can block TGF-β1 signaling,31 and stimulation of TGF-β1 can increase biliary senescence and fibrosis as reported by Zhou et al.39 In hepatocytes, miR-146a decreases hepatic fibrosis via TGF-β1/SMAD4 signaling with a subsequent inhibition of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, thus suggesting that TGF-β1 signaling can regulate EMT. This study demonstrates a reduction in portal fibrosis coupled with decreased large ductal TGF-β1 expression and serum secretion after inhibition of H2HR in Mdr2−/− mice. Furthermore, decreased vimentin expression but increased epithelial marker expression were observed after H2HR Vivo-morpholino treatment in Mdr2−/− mice compared with mismatch. How H2HR might regulate TGF-β1–mediated EMT has not been examined.

The role of vascular cells and/or contribution of angiogenesis during PSC has not been fully studied or characterized. These experiments reveal that there is decreased VEGF-A/C expression and VEGF-A secretion coupled with lower vWF levels that are mediated by H2HR signaling. To support this, a study by Wu et al40 also found that blocking miR-200b (which is increased in patients with PSC) decreases angiogenesis and subsequent fibrosis; however, the link between vascular cells and fibrosis-promoting cells, such as HSCs, is not well known. This study speculates that H2HR acts on large cholangiocytes to reduce biliary senescence, which may interact with vascular endothelial cells or MCs (which also express and secrete VEGF) to reduce angiogenesis, and because cholangiocytes also express and secrete VEGF, there may be autocrine and paracrine interactions at work during PSC. These studies need to be expanded to fully understand the role of angiogenesis during PSC progression.

In summary, this work demonstrates an important role for H2HR signaling in large ductal PSC that regulates ductular reaction, biliary senescence, fibrosis, and angiogenesis. Blocking H2HR vivo-morpholino decreased damaging phenotypes in Mdr2−/− mice and revealed potential signaling mechanisms involved in large cholangiocyte response. Understanding changes in biliary and liver damage based on specifically targeting large ducts is significant considering that approximately 90% of patients present with large duct PSC, which is associated with a higher risk of malignant tumors.41 This study verified previous findings demonstrating rigor and reproducibility and identified the mechanistic pathways mediated by H2HR inhibition that were not discussed in previous work. H2HR is up-regulated in human PSC, and inhibition of H2HR using over-the-counter blockers decreases disease progression. Coupled with findings from the current study, H2HR is a potential target for the clinical management of PSC.

Footnotes

Supported by an SRCS award (G.A.), US Department of Veterans Affairs Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service Merit Award 1I01BX003031 (H.F.), NIH grants DK108959 (H.F.) and DK119421 (H.F.), the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System, and the Richard L. Roudebush VA Medical Center.

Disclosures: None declared.

The content is the responsibility of the author(s) alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.01.013.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Evaluation of biliary proliferation. Proliferation was determined by staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in all groups. Similar to intrahepatic bile duct mass (IBDM), large biliary proliferation (arrows) increased in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch compared with wild-type (WT) mice, and this was significantly reduced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino. Staining was semiquantified using a light microscope. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. n = 10 representative images; n = 6 mice for each group. ∗P < 0.05 versus small and large PCNA from WT mismatch mice; †P < 0.05 versus large IBDM from Mdr2−/− + H2HR mismatch mice. Original magnification, ×40.

Supplemental Figure S2.

Determination of epithelial marker expression. Immunohistochemical expression of cytokeratin 18 (CK-18) (A) and E-cadherin (B) (arrows). Biliary expression of CK-18 and E-cadherin increases in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knockout mouse (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch compared with wild-type (WT) mice. Expression of CK-18 (A) and E-cadherin (B) is more enhanced in Mdr2−/− mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino compared with mismatch treated mice. No differences are seen between WT groups. Original magnification: ×40 (A and B, main images); ×100 (A and B, insets).

Supplemental Figure S3.

Measurement of von Willebrand factor (vWF) expression. Immunofluorescence shows that the expression of vWF increases in multidrug-resistance transporter 2/ABC transporter B family member 2 knock out (Mdr2−/−) mice treated with mismatch and surrounds large bile ducts [marked by cytokeratin (CK)-19 stained green] compared with wild-type (WT) groups. In Mdr2−/− mice treated with histamine-2 receptor (H2HR) vivo-morpholino, there is a decrease in vWF expression. No differences are seen between WT groups. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in the insets. Original magnification: ×40 (main images); ×100 (insets).

References

- 1.McDaniel K., Meng F., Wu N., Sato K., Venter J., Bernuzzi F., Invernizzi P., Zhou T., Kyritsi K., Wan Y., Huang Q., Onori P., Francis H., Gaudio E., Glaser S., Alpini G. Forkhead box A2 regulates biliary heterogeneity and senescence during cholestatic liver injury in micedouble dagger. Hepatology. 2017;65:544–559. doi: 10.1002/hep.28831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pollheimer M.J., Halilbasic E., Fickert P., Trauner M. Pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glaser S.S., Gaudio E., Rao A., Pierce L.M., Onori P., Franchitto A., Francis H.L., Dostal D.E., Venter J.K., DeMorrow S., Mancinelli R., Carpino G., Alvaro D., Kopriva S.E., Savage J.M., Alpini G.D. Morphological and functional heterogeneity of the mouse intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Lab Invest. 2009;89:456–469. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han Y., Glaser S., Meng F., Francis H., Marzioni M., McDaniel K., Alvaro D., Venter J., Carpino G., Onori P., Gaudio E., Alpini G., Franchitto A. Recent advances in the morphological and functional heterogeneity of the biliary epithelium. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2013;238:549–565. doi: 10.1177/1535370213489926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanno N., LeSage G., Glaser S., Alvaro D., Alpini G. Functional heterogeneity of the intrahepatic biliary epithelium. Hepatology. 2000;31:555–561. doi: 10.1002/hep.510310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clerbaux L.A., Manco R., Van Hul N., Bouzin C., Sciarra A., Sempoux C., Theise N.D., Leclercq I.A. Invasive ductular reaction operates hepatobiliary junctions upon hepatocellular injury in rodents and humans. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:1569–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDaniel K., Wu N., Zhou T., Huang L., Sato K., Venter J., Ceci L., Chen D., Ramos-Lorenzo S., Invernizzi P., Bernuzzi F., Wu C., Francis H., Glaser S., Alpini G., Meng F. Amelioration of ductular reaction by stem cell derived extracellular vesicles in MDR2 knockout mice via lethal-7 microRNA. Hepatology. 2019;69:2562–2578. doi: 10.1002/hep.30542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sato K., Marzioni M., Meng F., Francis H., Glaser S., Alpini G. Ductular reaction in liver diseases: pathological mechanisms and translational significances. Hepatology. 2019;69:420–430. doi: 10.1002/hep.30150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy L., Hargrove L., Demieville J., Karstens W., Jones H., DeMorrow S., Meng F., Invernizzi P., Bernuzzi F., Alpini G., Smith S., Akers A., Meadows V., Francis H. Blocking H1/H2 histamine receptors inhibits damage/fibrosis in Mdr2(-/-) mice and human cholangiocarcinoma tumorigenesis. Hepatology. 2018;68:1042–1056. doi: 10.1002/hep.29898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kyritsi K., Chen L., O'Brien A., Francis H., Hein T.W., Venter J., Wu N., Ceci L., Zhou T., Zawieja D., Gashev A.A., Meng F., Invernizzi P., Fabris L., Wu C., Skill N.J., Saxena R., Liangpunsakul S., Alpini G., Glaser S. Modulation of the TPH1/MAO-A/5HT/5HTR2A/2B/2C axis regulates biliary proliferation and liver fibrosis during cholestasis. Hepatology. 2020;71:990–1008. doi: 10.1002/hep.30880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vries E., Beuers U. Management of cholestatic disease in 2017. Liver Int. 2017;37 Suppl 1:123–129. doi: 10.1111/liv.13306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fickert P., Wagner M., Marschall H.U., Fuchsbichler A., Zollner G., Tsybrovskyy O., Zatloukal K., Liu J., Waalkes M.P., Cover C., Denk H., Hofmann A.F., Jaeschke H., Trauner M. 24-norUrsodeoxycholic acid is superior to ursodeoxycholic acid in the treatment of sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:465–481. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Francis H., Franchitto A., Ueno Y., Glaser S., DeMorrow S., Venter J., Gaudio E., Alvaro D., Fava G., Marzioni M., Vaculin B., Alpini G. H3 histamine receptor agonist inhibits biliary growth of BDL rats by downregulation of the cAMP-dependent PKA/ERK1/2/ELK-1 pathway. Lab Invest. 2007;87:473–487. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Francis H., Glaser S., Demorrow S., Gaudio E., Ueno Y., Venter J., Dostal D., Onori P., Franchitto A., Marzioni M., Vaculin S., Vaculin B., Katki K., Stutes M., Savage J., Alpini G. Small mouse cholangiocytes proliferate in response to H1 histamine receptor stimulation by activation of the IP3/CaMK I/CREB pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C499–C513. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis H., Meng F., Gaudio E., Alpini G. Histamine regulation of biliary proliferation. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1204–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis H.L., Demorrow S., Franchitto A., Venter J.K., Mancinelli R.A., White M.A., Meng F., Ueno Y., Carpino G., Renzi A., Baker K.K., Shine H.E., Francis T.C., Gaudio E., Alpini G.D., Onori P. Histamine stimulates the proliferation of small and large cholangiocytes by activation of both IP3/Ca2+ and cAMP-dependent signaling mechanisms. Lab Invest. 2012;92:282–294. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2011.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borriello F., Iannone R., Marone G. Histamine release from mast cells and basophils. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2017;241:121–139. doi: 10.1007/164_2017_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang H., Li Y., Liang J., Finkelman F.D. Molecular regulation of histamine synthesis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1392. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hargrove L., Kennedy L., Demieville J., Jones H., Meng F., DeMorrow S., Karstens W., Madeka T., Greene J., Jr., Francis H. BDL-induced biliary hyperplasia, hepatic injury and fibrosis are reduced in mast cell deficient Kitw-sh mice. Hepatology. 2017;65:1991–2004. doi: 10.1002/hep.29079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson C., Huynh V., Hargrove L., Kennedy L., Graf-Eaton A., Owens J., Trzeciakowski J.P., Hodges K., DeMorrow S., Han Y., Wong L., Alpini G., Francis H. Inhibition of mast cell-derived histamine decreases human cholangiocarcinoma growth and differentiation via c-kit/stem cell factor-dependent signaling. Am J Pathol. 2016;186:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones H., Hargrove L., Kennedy L., Meng F., Graf-Eaton A., Owens J., Alpini G., Johnson C., Bernuzzi F., Demieville J., DeMorrow S., Invernizzi P., Francis H. Inhibition of mast cell-secreted histamine decreases biliary proliferation and fibrosis in primary sclerosing cholangitis Mdr2-/- mice. Hepatology. 2016;64:1202–1216. doi: 10.1002/hep.28704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graf A., Meng F., Hargrove L., Kennedy L., Han Y., Francis T., Hodges K., Ueno Y., Nguyen Q., Greene J.F., Francis H. Knockout of histidine decarboxylase decreases bile duct ligation-induced biliary hyperplasia via downregulation of the histidine decarboxylase/VEGF axis through PKA-ERK1/2 signaling. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G813–G823. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00188.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meng F., Onori P., Hargrove L., Han Y., Kennedy L., Graf A., Hodges K., Ueno Y., Francis T., Gaudio E., Francis H.L. Regulation of the histamine/VEGF axis by miR-125b during cholestatic liver injury in mice. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kennedy L., Hargrove L., Demieville J., Bailey J., Dar W., Polireddy K., Chen Q., Nevah Rubin M.I., Sybenga A., DeMorrow S., Meng F., Stockton L., Alpini G., Francis H. Knockout of l-Histidine decarboxylase prevents cholangiocyte damage and hepatic fibrosis in mice subjected to high-fat diet feeding via disrupted histamine/leptin signaling. Am J Pathol. 2018;188:600–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popov Y., Patsenker E., Fickert P., Trauner M., Schuppan D. Mdr2 (Abcb4)-/- mice spontaneously develop severe biliary fibrosis via massive dysregulation of pro- and antifibrogenic genes. J Hepatol. 2005;43:1045–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyritsi K., Meng F., Zhou T., Wu N., Venter J., Francis H., Kennedy L., Onori P., Franchitto A., Bernuzzi F., Invernizzi P., McDaniel K., Mancinelli R., Alvaro D., Gaudio E., Alpini G., Glaser S. Knockdown of hepatic gonadotropin-releasing hormone by vivo-morpholino decreases liver fibrosis in multidrug resistance gene 2 knockout mice by down-regulation of miR-200b. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:1551–1565. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan Y., McDaniel K., Wu N., Ramos-Lorenzo S., Glaser T., Venter J., Francis H., Kennedy L., Sato K., Zhou T., Kyritsi K., Huang Q., Annable T., Wu C., Glaser S., Alpini G., Meng F. Regulation of cellular senescence by miR-34a in alcoholic liver injury. Am J Pathol. 2017;187:2788–2798. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy L.L., Hargrove L.A., Graf A.B., Francis T.C., Hodges K.M., Nguyen Q.P., Ueno Y., Greene J.F., Meng F., Huynh V.D., Francis H.L. Inhibition of mast cell-derived histamine secretion by cromolyn sodium treatment decreases biliary hyperplasia in cholestatic rodents. Lab Invest. 2014;94:1406–1418. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meadows V., Kennedy L., Hargrove L., Demieville J., Meng F., Virani S., Reinhart E., Kyritsi K., Invernizzi P., Yang Z., Wu N., Liangpunsakul S., Alpini G., Francis H. Downregulation of hepatic stem cell factor by Vivo-Morpholino treatment inhibits mast cell migration and decreases biliary damage/senescence and liver fibrosis in Mdr2(-/-) mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2019;1865:165557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2019.165557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng F., Han Y., Staloch D., Francis T., Stokes A., Francis H. The H4 histamine receptor agonist, clobenpropit, suppresses human cholangiocarcinoma progression by disruption of epithelial mesenchymal transition and tumor metastasis. Hepatology. 2011;54:1718–1728. doi: 10.1002/hep.24573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moncsek A., Al-Suraih M.S., Trussoni C.E., O'Hara S.P., Splinter P.L., Zuber C., Patsenker E., Valli P.V., Fingas C.D., Weber A., Zhu Y., Tchkonia T., Kirkland J.L., Gores G.J., Mullhaupt B., LaRusso N.F., Mertens J.C. Targeting senescent cholangiocytes and activated fibroblasts with B-cell lymphoma-extra large inhibitors ameliorates fibrosis in multidrug resistance 2 gene knockout (Mdr2-/-) mice. Hepatology. 2018;67:247–259. doi: 10.1002/hep.29464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou T., Kyritsi K., Wu N., Francis H., Yang Z., Chen L., O'Brien A., Kennedy L., Ceci L., Meadows V., Kusumanchi P., Wu C., Baiocchi L., Skill N.J., Saxena R., Sybenga A., Xie L., Liangpunsakul S., Meng F., Alpini G., Glaser S. Knockdown of vimentin reduces mesenchymal phenotype of cholangiocytes in the Mdr2(-/-) mouse model of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) EBioMedicine. 2019;48:130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horvath Z., Pallinger E., Horvath G., Jelinek I., Falus A., Buzas E.I. Histamine H1 and H2 receptors but not H4 receptors are upregulated during bone marrow regeneration. Cell Immunol. 2006;244:110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng F., Kennedy L., Hargrove L., Demieville J., Jones H., Madeka T., Karstens A., Chappell K., Alpini G., Sybenga A., Invernizzi P., Bernuzzi F., DeMorrow S., Francis H. Ursodeoxycholate inhibits mast cell activation and reverses biliary injury and fibrosis in Mdr2(-/-) mice and human primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lab Invest. 2018;98:1465–1477. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0101-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hall C., Ehrlich L., Meng F., Invernizzi P., Bernuzzi F., Lairmore T.C., Alpini G., Glaser S. Inhibition of microRNA-24 increases liver fibrosis by enhanced menin expression in Mdr2(-/-) mice. J Surg Res. 2017;217:160–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wechsler J.B., Schroeder H.A., Byrne A.J., Chien K.B., Bryce P.J. Anaphylactic responses to histamine in mice utilize both histamine receptors 1 and 2. Allergy. 2013;68:1338–1340. doi: 10.1111/all.12227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romero S.A., McCord J.L., Ely M.R., Sieck D.C., Buck T.M., Luttrell M.J., MacLean D.A., Halliwill J.R. Mast cell degranulation and de novo histamine formation contribute to sustained postexercise vasodilation in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2017;122:603–610. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00633.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pagotto R.M., Monzon C., Moreno M.B., Pignataro O.P., Mondillo C. Proliferative effect of histamine on MA-10 Leydig tumor cells mediated through HRH2 activation, transient elevation in cAMP production, and increased extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation levels. Biol Reprod. 2012;87:150. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.102905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou T., Wu N., Meng F., Venter J., Giang T.K., Francis H., Kyritsi K., Wu C., Franchitto A., Alvaro D., Marzioni M., Onori P., Mancinelli R., Gaudio E., Glaser S., Alpini G. Knockout of secretin receptor reduces biliary damage and liver fibrosis in Mdr2(-/-) mice by diminishing senescence of cholangiocytes. Lab Invest. 2018;98:1449–1464. doi: 10.1038/s41374-018-0093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu N., Meng F., Zhou T., Han Y., Kennedy L., Venter J., Francis H., DeMorrow S., Onori P., Invernizzi P., Bernuzzi F., Mancinelli R., Gaudio E., Franchitto A., Glaser S., Alpini G. Prolonged darkness reduces liver fibrosis in a mouse model of primary sclerosing cholangitis by miR-200b down-regulation. FASEB J. 2017;31:4305–4324. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700097R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weismuller T.J., Trivedi P.J., Bergquist A., Imam M., Lenzen H., Ponsioen C.Y. Patient age, sex, and inflammatory bowel disease phenotype associate with course of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1975–1984.e8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]