Abstract

Erwinia carotovora is a major cause of potato tuber infection, which results in disastrous failures of this important food crop. There is currently no effective antibiotic treatment against E. carotovora. Recently we reported antibacterial assays of wound tissue extracts from four potato cultivars that exhibit a gradient of russeting character, finding the highest potency against this pathogen for a polar extract from the tissue formed immediately after wounding by an Atlantic cultivar. In the current investigation, antibacterial activity-guided fractions of this extract were analyzed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) utilizing a quadrupole-time-of-flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer. The most active chemical compounds identified against E. carotovora were: 6-O-nonyl glucitol, Lyratol C, n-[2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)] ethyldecanamide, α-chaconine and α-solanine. Interactions among the three compounds, ferulic acid, feruloyl putrescine, and α-chaconine, representing metabolite classes upregulated during initial stages of wound healing, were also evaluated, offering possible explanations for the burst in antibacterial activity after tuber wounding and a chemical rationale for the temporal resistance phenomenon.

Keywords: Erwinia carotovora, Solanum tuberosu, Potato, Wound periderm, Antibacterial, LC-MS, TOF-MS

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Solanum tuberosum, commonly known as the potato, has the status of the fourth largest crop production worldwide. Potatoes are also highly popular edible tubers and represent the third largest crop with respect to global consumption. This type of tuber not only represents a staple of the human diet, but it also plays an important role in the world economy.1 Potato growers face numerous practical challenges when it comes to the production, storage and processing of tubers. These difficulties are exemplified by the statistic that roughly half of harvested tubers fail to reach the market for consumption, thus representing substantial crop losses.2

The chemical composition of potato tubers includes about 80% water by mass and is rich in starch. Hence, potatoes exhibit high susceptibility to bacterial infection.3 For instance, potatoes are vulnerable to Erwinia carotovora, a Gram-negative bacterium that infects and promotes the formation of soft rot and lenticel spot. Soft rot has been attributed to species of the Pectobacterium harvesting, involves pectolytic action that causes deterioration of the plant cell walls. Lenticel spot can be caused by several species belonging to the Pectobacterium genus.3 The lack of bactericides for diseases caused by these infections is a major ongoing agricultural concern. Thus, the goal of this study was to develop chemically based strategies for the inhibition of E. carotovora infection in tubers, with the long-term goal of mitigating the associated crop damage. We sought to identify potent antimicrobial compounds from metabolite mixtures generated by the potato itself, molecules that can prevent microbial infection.

Once potato tubers are wounded, they become highly vulnerable to dehydration and infection, particularly before the suberin biopolyester is deposited on the periderm tissue surface as a protective layer after 1–2 weeks. During the time prior to formation of this layer, it has been hypothesized that other means of so-called temporal resistance must emerge to provide protection against pathogens.4 These defensive measures include production of compounds that may appear due to oxidative bursts, phytoalexin production, and/or pathogenesis-related protein synthesis.5 Our recent studies of this phenomenon include the demonstration of significantly higher antibacterial activity against E. carotovora for extracts of wound periderm tissues obtained at early time points (days 0, 1 and 2) as compared with extracts derived from later time points (days 3 and 7). In particular, robust activity was found in polar extracts from a three-phase extraction of the wound tissues, which contain metabolites such as phenolic acids, phenolic amines, and glycoalkaloids. This antibacterial activity was comparable to that of ampicillin, a standard Gram-negative antibiotic.6

The highest antibacterial activity among the four cultivars (Norkotah Russet, Atlantic, Chipeta and Yukon Gold) was exhibited during the course of temporal resistance by the day-0 wound tissue extract from the Atlantic potato cultivar (Wd0A).6 Therefore, in the current investigation this extract was used for antibacterial activity-guided fractionation in order to elucidate the chemical basis of this protective property. The phytochemical constituents were separated by high-performance liquid chromatography, identified by mass spectrometry, and assayed for antibacterial activity by measuring percentage growth inhibition and potency per unit mass. Compounds representing the major metabolite classes were tested for potency and potentiating interactions. Our analysis should help to identify specific compounds that are the major contributors, individually or in concert, to the highly potent antibacterial activity displayed by the Wd0A extract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material

Four different cultivars of Solanum tuberosum (potato) from the 2015 crop were obtained from Dr. David G. Holm (Colorado State University). In order of increasing skin russeting character they were Yukon Gold, Chipeta, Atlantic (reported herein), and Norkotah Russet. The polar extract obtained at day 0 after wounding from the Atlantic cultivar, which displayed the highest antibacterial activity, was analyzed in the current study as described in the sections below.

2.2. Chemicals and reagents

For extractions, analytical grade methanol and chloroform were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). HPLC–MS grade water, methanol, acetonitrile (J. T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ), and formic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were utilized in HPLC, LC–MS, and TOF-MS analyses. For antibacterial assays, the standard compounds were α-chaconine (CH) (ICC, Hillsborough, NJ), ferulic acid (FA) (Sigma, Burlington, MA), feruloylputrescine (FP) (BOC Science, Shirley, NY) and ampicillin (AMP) (Sigma, San Jose, CA).

2.3. Preparation of potato periderm extracts

Extract preparation was carried out following previously described procedures, using a multi-solvent protocol that generated soluble polar, soluble nonpolar, and suspended solid phases simultaneously from each tissue sample.6

2.4. Extract Fractionation by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC)

To analyze the chemical composition of the Wd0A polar extract and isolate the major contributors to the measured antibacterial activity, activity-guided fractionation was conducted. Reverse-phase HPLC separation was carried out using an Agilent Series 1200 instrument (Santa Clara, CA) with an AscentisR 150 × 4.6 mm, 3.0 μm C18 column (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). This instrument is equipped with a G1311A quaternary pump, G1322A degasser, G1316A temperature controller, and G1315B diode array detector coupled to a G1364C analytical fractionator. Each analysis was performed by injecting a 30-μL sample into the column and eluting with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min. The mobile phase was composed of 0.1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid (A) and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The following program of stepwise non-linear elution was used: 2% B (0–5 min), 10% B (5–8 min), 15% B (8–25 min), 100% B (25–38 min), and 2% B (38–50 min). Collection of 40 fractions was performed in time-based mode from 3 to 38 min during a 65-min chromatographic run that was repeated fifteen times to provide enough material for subsequent structural analysis.6

2.5. Antibacterial activity of fractions from the polar extracts

Bacterial cultures of E. carotovora (ECC15) were provided by Dr. Anuradha Janakiraman (City College of New York). Bacterial cultures were streaked and diluted into 2 mL of liquid Mueller-Hinton medium, then incubated overnight by shaking at 250 rpm and 30 °C. After incubation, the optical density of each bacterial culture was used as a measure of the cell density; this reading determined the dilution factor required to obtain reliable spectrophotometer absorbance (Abs) readings in the range of 0.05 to 0.60 at 600 nm.

A 96-well plate was used to assess the activity of the polar Wd0A extract against the bacterial cultures. Six replicates of each fraction (1 to 40) at day 0 (4 hours after wounding was induced) were selected for testing together with ampicillin (AMP, positive control) and 60% (v/v) methanol-water (solvent; negative control). The percentage inhibition for each extract was calculated with equation (1):6

| (1) |

2.6. Antibacterial potency

The potency of fractions 1 to 40 (F1–F40) was determined in two ways: based on area under the curve (AUC) and based on percentage inhibition. Potency based on AUC (PAUC) is the ratio of each fraction’s AUC for the full 15-hour length of incubation to its mass in mg. Potency based on inhibition (Pi) is determined four hours after bacterial culture incubation with each fraction, again normalized according to the sample mass. Both analyses of potency offer more accurate assessments of the antibacterial activity for the different fractions than by looking solely at percent inhibition, which does not account for the mass of each fraction. In addition, potency evaluated across the incubation time sorts out the possible types of antibacterial effects by considering the entire course of bacterial growth.

SigmaPlot software was used to calculate AUCs utilizing two distinct algorithms. The first alternative was the integration function, which employs the trapezoidal rule. This rule uses the values measured during each hour, integrating over n time subintervals and employing linear piecewise interpolation as shown in equation (2)7:

| (2) |

The values obtained from the above method were confirmed with a determination based on Simpson’s rule. Instead of the linear approximation employed by the former method, this rule utilizes a quadratic interpolation to estimate definite integrals as shown in equation (3)7:

| (3) |

To take the fraction mass into account for the determination of activity, we calculated PAUC and Pi using Equations (4) and (5), respectively:

| (4) |

| (5) |

2.7. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) Analysis

Fractions from the Wd0A extract were analyzed utilizing an Agilent 6550 QTOF mass spectrometer (Hunter College) equipped with a 1200 Series capillary HPLC system. The chromatography mode used a reverse phase C18 column (Agilent Poroshell 120, SB-C18, 2.1×50 mm), a column temperature set to 30 °C, and an injection volume of 10 μL for each sample. The development solvent consisted of 0.1% (v/v) aqueous formic acid (A) and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile (B). A 0.4 mL/min flow rate was used, with gradient elution conducted as follows: 2% B for 1 min, 2% to 98% B (1–20 min), 98% B for 2 min, 2% B for 6 min. Positive and negative ion modes of electrospray ionization were used in separate experiments to obtain mass spectra in the range m/z 100–1500. Parameters for the mass spectrometer included the following: gas temperature of 250 °C, drying gas flow rate of 17 L/min, nebulizer pressure of 30 psig, sheath gas temperature of 250 °C, Vcap, 3500 V; nozzle voltage, 2000 V; reference masses for positive and negative modes of 121.0508/922.0097 and 112.9855/1033.9881, respectively. Data acquisition and processing were carried out by utilizing Agilent’s Mass Hunter workstation software, which has built-in LC/MS Data Acquisition (vB.05.01) and Qualitative Analysis (vB.06.00) modules.6

2.8. Structural identification of fractionated antibacterial samples

Drawing on results from the LC-MS measurements described above, namely the m/z values of the fragment and molecular ions, elemental isotopic ratio analysis was performed utilizing Agilent’s Mass Hunter workstation software. This analysis specifies possible molecular formulas that fall within a selected error frame (typically ±30 ppm mass units). Once a molecular formula is determined, a search for possible structures is conducted using different sources of published literature such as SciFinder Scholar and Google Scholar. This literature search is refined by taking into account all possible formulas previously identified and analyzed in Solanum tuberosum and in the Solanaceae plant family. In order to make the best selection when matching the experimental data with identified structures, we considered the molecular ions and fragmentation data in published work that best conformed to our results.

2.9. Antimicrobial assessment of standard compounds

The antimicrobial activity of the following standard compounds, representing the major classes of phytochemical compounds found in the polar extracts of Wd0A potato wound tissue extracts, was tested against E. carotovora over 15 hours of incubation: CH, FA, and FP.6 In order to compare the antibacterial activities of the standards with a positive control (AMP), their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) were measured. The MIC refers to a concentration threshold, below which there is no antibacterial activity. This is usually stated as a concentration for which the antibacterial activity is less than 5% within a defined period of time.8

2.10. Synergism assays

The standard compounds (CH, FA, and FP) were each tested by antibacterial assays in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with the AMP positive control. The concentration of each standard compound was kept at 0.5 mg/ml, both in the presence and absence of the fractions from the tissue extracts, to obtain a valid measure of synergistic activity.

2.11. Microscopic analysis

Microscopic analysis was carried out by previously described procedures.6 Briefly, concentrations of 0.5 and 1.0 mg/mL were used for each of the standard compounds (AMP, CH, FA, and FP) and for the most potent fractions (F7, F16 and F17). These solutions were incubated with the E. carotovora cultures for a 4-h period prior to imaging with a light microscope from Nikon Instruments (Melville, NY).

3. Results

3.1. Potency

As noted in the Introduction, we employed reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a stepwise linear gradient to separate the phytochemical constituents responsible for the antibacterial activity found in post-wound potato tissue extract fractions. After exposure of each fraction to E. carotovora during the log phase of growth, antibacterial activity was measured in terms of percentage growth inhibition and potency per unit mass. Subsequently, structural identification of metabolites present in the most active fractions was carried out utilizing liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) with a quadrupole-time-of-flight (QTOF) mass spectrometer.6

The potency of each fraction was assessed by determinations of Pi and PAUC. The most potent fractions based on values of Pi, in order of highest to lowest potency, were fractions 17 (F17), F7, and F16 (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, the potency profile changed slightly when based on the area under the curve during the full length of the assay (PAUC): the most potent fractions were F17, F16 and then F7 (Fig. 1B). Thus F17 displayed the highest potency judged by both Pi and PAUC, whereas F7 had a higher Pi but a lower PAUC than F16. Differences in the Pi and PAUC potency profiles indicated that F17 exhibits the highest potency during the entirety of the growth curve, while F16 and F7 were second most potent at all growth curve phases and second most potent at log phase, respectively. For both types of determined potency, several fractions displayed no detectable activity. This trend is illustrated by the notably higher antibacterial activity displayed by F7, F16 and F17, (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Antibacterial potency of Atlantic cultivar day 0 wound extract fractions determined by two methods. A: potency based on percentage inhibition (Pi/mass) was calculated at 4 hours of bacterial culture after exposure to each fraction. B: potency based on Area Under the Curve (PAUC/mass) over 15 hours of incubation. Error bars represent the standard error values from the six replicates for each fraction. NA indicates not active.

3.2. Compound identification

The most potent fractions, F17, F16, and F7, were further analyzed to achieve chemical identification by using data from LC-MS Q-Trap and QTOF experiments (Table 1). Chemical compounds were identified in each fraction. F7 contained 6-O-nonyl-glucitol and Lyratol C. Whereas F7 contained compounds specific to this fraction, F16 and F17 shared two constituents: α-solanine and α-chaconine. F17 also contained N-[2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)] ethyl] decanamide. Previously reported antibacterial activity of these compounds is summarized in the Discussion section.

Table 1.

Chemical constituents found in Wd0A polar fractions of wound-healing potato periderma

|

Molecular structures were determined for 5 of the 6 isolated compound

3.3. Antimicrobial assessment of standard compounds

Once we had elucidated the major compounds present in the most active polar fractions of the highly active Wd0A potato wound tissue extract, we focused our antimicrobial assessment on their respective compound classes. Fig. 2 shows that each of the standard phytochemical compounds (chaconine, CH; feruloylputrescine, FP; ferulic acid, FA) displays dose-dependent levels of inhibitory activity against the E. carotovora bacterial strain. For instance, chaconine is a major compound found in the polar extract and also a major compound found in the most active fractions 16 and 17. Fig. 2 displays the MIC values for FP, FA and CH: whereas FP and FA have a range of MIC values from 0.01 to 0.1 mM, CH and the positive control (ampicillin, AMP) have the same MIC range, 0.1–1.0 mM. Thus, FA and FP were more active against E. carotovora than the ampicillin positive control. However, the potency of CH is similar to ampicillin.

Fig. 2.

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration against E. carotovora of compounds representing the major classes identified in Atlantic cultivar day 0 wound extract. Standard compounds (chaconine, CH; feruloylputrescine, FP; ferulic acid, FA; and ampicillin, AMP) are examined at different concentrations. Error bars represent the standard error values from the six replicates for each sample. NA indicates not active.

3.4. Interactions among active compound classes

In addition, various interactions among the most potent fractions and standards were investigated. These studies were conducted because, rather than individual compounds, it could be the mixture of antibacterial compounds in the plant extract that is responsible for improved efficacy of antibacterial activity.9 Interaction types were designated as follows: addition refers to the interaction of two compounds as the sum of their individual activities, potentiation describes the effect of two compounds in a mixture yielding a larger activity that the sum of their individual activities, synergism is an effect in which two compounds have a higher activity than their individual activities but lower than their summed effect, and antagonism denotes an effect produced by the two compounds that is less than the activity of either one of them.9

The standard compounds used, ferulic acid, feruloyl putrescine, and chaconine, were wound-healing marker compounds that were statistically elevated in Wd0A extracts. Each compound also represents a major metabolite class present in the wound tissue extract: ferulic acid, feruloyl putrescine, and chaconine represent phenolic acids, phenolic amines, and glycoalkaloids, respectively. These compounds were assessed for their potency with respect to the positive control compound ampicillin, an antibiotic used against Gram-negative bacteria. The standard compounds were also investigated for their interactions with the positive control. Ability to potentiate the antibacterial activity of ampicillin could prove to be extremely useful, as a lower concentration of the standard compound and the positive control could then be used in the treatment of E. carotovora infection. It is also interesting to assess the interactions among standard compounds, potentially yielding greater insights into the effect of phytochemical compounds present in the Wd0A potato extract on the ultimate antibacterial activity. Ultimately, our aim is to uncover naturally produced compounds that can reduce potato crop waste due to bacterial infection and to gain further insight into the potato wound-healing process at the molecular level.

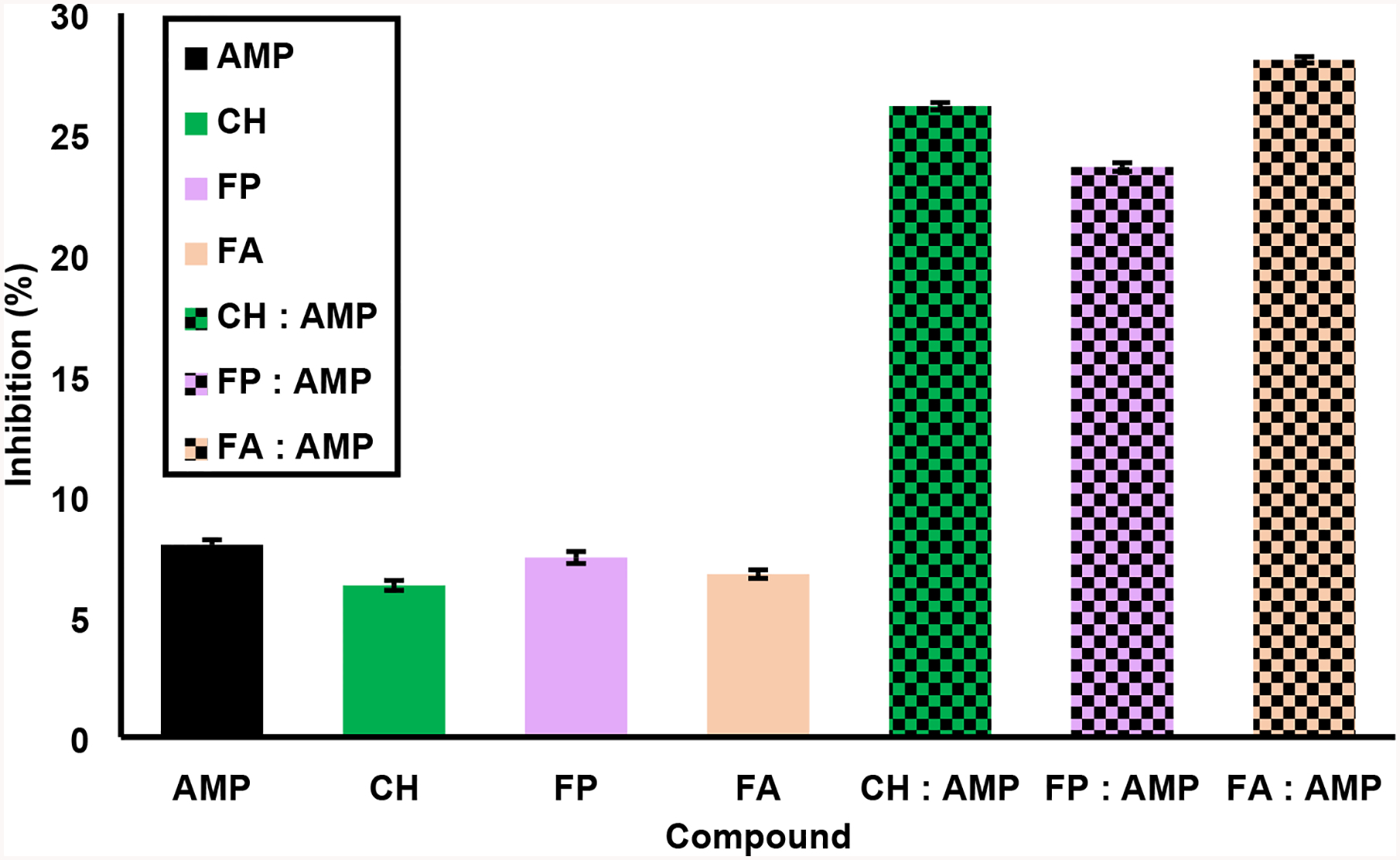

Fig. 3 compares the levels of bacterial growth inhibition for each of the standard compounds, either on their own or when combined with the AMP positive control. The concentration of each compound alone was 0.5 mg/mL, and the concentrations in the mixture of each compound with AMP were maintained at the same value, permitting the interaction of CH, FP, or FA with the positive control to be evaluated straightforwardly. The inhibition values of the standards in combination with AMP were in all cases greater than the sum of the individual inhibition values, indicating synergistic activity with the positive control at a level showing potentiation. The order of potentiation with AMP is as follows: FA> CH> FP.

Fig. 3.

Synergism studies of standard compounds in combination with ampicillin. Antibacterial activity based on percentage inhibition was calculated at 4 hours of bacterial culture after exposure to a positive control (ampicillin, AMP) mixed with standard compounds (chaconine, CH; feruloylputrescine, FP; and ferulic acid, FA). The first (solid) bar of each set represents each compound at 0.5 mg/mL, while the second (checkerboard) bar of each pair shows the standard compound with ampicillin, each at a concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. Error bars represent the standard error values from the six replicates for each sample.

The interactions between the standard compounds are assessed in Fig. 4. The concentration of each standard compound individually was 0.5 mg/mL and the concentration of each compound in the mixture was also 0.5 mg/mL, hence the inhibitory activity of their combinations could again be examined easily. The individual percentage activities of each compound were as follows: CH (~6%), FA (~7%), and FP (~7%). Given these individual values, the following trends were observed for the mixtures: the inhibitory activity of CH in combination with FA (CH:FA) was ~16%, slightly greater than the sum of CH and FA. This result suggests addition of their antibacterial activity. On the other hand, the activities of FP:FA (~9%) and FP:CH (~11%) were lower than the sum of each corresponding set but higher than either individual compound’s activity, indicating synergism.

Fig. 4.

Synergism of standard compounds and pairwise mixtures. The concentration of each compound alone is 0.5 mg/mL, while the final concentration of each standard compound combination sample is also 0.5 mg/mL. Solid colors signify each standard compound (chaconine, CH; feruloylputrescine, FP; and ferulic acid, FA) alone; checkerboard patterns designate a combined sample. Error bars represent the standard error values from the six replicates for each sample.

3.5. Microscopic analysis

Imaging of bacteria treated with antibacterial compounds or tissue extract fractions can offer insight into bactericidal effects other than cell lysis that are not revealed by changes in absorbance.6 The variety of morphological changes effected in E. carotovora when exposed to the most potent fractions (F7, F16 and F17) and the standard compounds (AMP, FP, FA and CH) are displayed in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. Both morphological changes and cell lysis were observed.

Fig. S1 shows the impact on the fractions tested against the bacterial culture. Cell lysis increases with concentration, from 0.5 mg/mL to 1.0 mg/mL, as does cell filamentation. S2 illustrates the exposure of standard compounds to the bacterial culture. Here it is observed that AMP has a drastic impact on cell morphology, elongating and widening the bacterial cells. Analogous increases in cell lysis were also observed for FA, CH and FP, as well as changes in cell morphology with FP. These morphological changes, which are not evident in absorbance assays, may result from inhibition of bacterial division and/or alterations in cell permeability.

4. Discussion

The potency results shown in Fig. 1 demonstrate differences in the order of antibacterial activity against E. carotovora among the most potent fractions (F7, F16 and F17) according to whether Pi or PAUC values were used for this assessment. This contrast demonstrates that some antibacterial components in the fraction are active only during the log phase of bacterial growth (e.g., compounds in F7), whereas others show antibacterial efficacy throughout the bacterial growth period of the assay (e.g., compounds in F16 and F17).

The identified compounds open a window into the chemical constituents that underlie temporal resistance in the most potent antibacterial polar potato Wd0A extract. As described in Table 1, F7 was found to contain 6-O-nonyl glucitol and lyratol C. There is no antibacterial activity reported for compound 1, 6-O-nonyl glucitol. However, lyratol C, compound 2, has been found to be the main antibacterial compound in a Santolina corsica essential oil that is active against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria (such as E. coli).10 This compound has also been reported for its cytotoxic activity against human cancer cell lines.11 Finally F17 contained n-[2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethyldecanamide, α-solanine, and α-chaconine, compounds 3, 4, and 5. F16 and F17 both contained α-solanine and α-chaconine. No antimicrobial effects have been reported to date for compound 3. The glycoalkaloid chaconine exhibits Gramnegative antibacterial activity as shown in Fig. 2. α-Chaconine and α-solanine have also been reported for their antifungal, insecticidal, and anticancer properties.12–14 As an anticancer agent, chaconine is thought to induce apoptosis in carcinogenic liver cells.12 In addition, glycoalkaloids have been reported to be generated as a stress response in post-wounding potato skin tissues.6 Thus, these findings indicate that the most active antibacterial fractions from the Wd0A extract are polar compounds with a mix of previously reported and newly discovered antibacterial properties.

The results of our interaction studies involving the active compound classes clearly demonstrate potentiation by the standards toward ampicillin as a positive control for antibacterial activity. However, the degree of potentiation activity varies among the compounds. All compounds potentiate the antibacterial activity of AMP to a significantly high level (Fig. 3), with ferulic acid displaying the greatest potentiation effect among the standards. Prior investigators have found that ferulic acid and p-coumaric acid synergize amikacin’s antibacterial activity against Gram-negative bacteria, proposing a mechanism based on increases in the bacterial membrane permeability towards the antibiotic in question or interactions with different targets by different components.15,16 Some bacteria are effective in removing the antibiotic with the help of efflux pumps (EPs), and therefore phytochemical substances inhibiting EPs can potentiate the antibacterial activity of established antibiotics. The latter property could have practical significance, because it demonstrates the potential for using lower doses of antibacterial compounds in formulations designed to treat E. carotovora infestation in potato tubers.

Interaction studies among the standard compounds (FA, FP and CH) demonstrate effects of addition and synergism on antibacterial activity. The FA:CH combination displayed addition, whereas synergism was observed for the combinations FP:FA and FP:CH (Fig. 4).

In addition, antifungal and Gram-negative antibacterial properties have been reported for phenolic amine compounds such as feruloyl putrescine and feruloyl tyramine.17, 18 Our imaging analysis revealed a subtle dose-response activity for the fractions and standards, mainly involving increased cell lysis. In addition, increases in the cell width and filamentation seen in AMP-treated samples were observed in cell cultures exposed to FP, suggesting the possibility of comparable activity and/or shared antibacterial targets to that of the known antibiotic.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study offer important insight into the possible action of antibiotic compounds produced endogenously by the potato against E. carotovora. First, we found that metabolites produced at elevated levels by the potato during initial stages of wound-healing process can act synergistically in combination with each other, offering a rationale for the burst in antibacterial activity of the Wd0A extract and a possible explanation for the underlying temporal resistance of potato tubers.6 In addition, compounds from the marker compound classes exhibited antibacterial activity potentiation of a widely used antibiotic, ampicillin. Although provisional, the mechanism of bacterial growth inhibition can further be suggested to have different targets for ampicillin and our compounds, thus potentiating ampicillin’s activity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

The most potent antibacterial fractions from the Atlantic potato wound tissue extract contained the glycoalkaloid α-chaconine in high abundance.

α-Chaconine had the same minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) as the ampicillin antibiotic, but feruloyl putrescine and ferulic acid showed lower MIC values.

α-Chaconine, feruloyl putrescine, and ferulic acid potentiated ampicillin’s antibacterial effects.

Pairs of these compounds demonstrated synergistic and additive antibacterial effects that suggest a rationale for tuber defense directly after wounding.

Acknowledgments

The potato tubers were supplied by Dr. David Holm (Colorado State U.). We thank Dr. Anuradha Janakiraman and Mr. Aaron Mychack (CUNY City College of New York) for providing the E. carotovora (ECC15), equipment access, and technical assistance for the antibacterial assays. This work was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF MCB-1411984 to R.E.S.); M.P.R. was a participant in the Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program under this grant award. Additionally, the work was underwritten by fellowships to M.P.R. at CCNY’s NSF REU site in Biochemistry, Biophysics, and Biodesign (NSF DBI-1560384), the NYC Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation CUNY (NSF HRD-1202520); an NIH Maximizing Access to Research Careers Program at CCNY (NIH 5T34GM007639-37), the City College Fellowship Program, and the American Chemical Society Scholars program. The QTOF MS instrument was acquired through NSF award CHE-1228921 (Hunter Mass Spectrometry, Hunter College, CUNY). Infrastructural support was provided by The City College of New York, the CUNY Institute for Macromolecular Assemblies, and a grant from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (5G12MD007603-30, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interest

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

We confirm that the manuscript has been read and approved by all named authors and that there are no other persons who satisfied the criteria for authorship but are not listed. We further confirm that the order of authors listed in the manuscript has been approved by all of us.

We confirm that we have given due consideration to the protection of intellectual property associated with this work and that there are no impediments to publication, including the timing of publication, with respect to intellectual property. In so doing we confirm that we have followed the regulations of our institutions concerning intellectual property. We the Corresponding Authors are the sole contact for the Editorial process (including Editorial Manager and direct communications with the office). We are responsible for communicating with the other authors about progress, submissions of revisions and final approval of proofs.

Sincerely,

Ruth E. Stark rstark@ccny.cuny.edu, Keyvan Dastmalchi, drk1dast@yahoo.com, Director, CUNY Institute for Senior, Research Associate, Macromolecular Assemblies, CUNY Distinguished Professor and Member of Doctoral Faculties, Professor and Chair, Department of City, College of New York (CCNY), Chemistry & Biochemistry, CCNY City, University of New York (CUNY)

References and notes

- 1.Thompson MD; Thompson HJ; McGinley JN, et al. Functional food characteristics of potato cultivars (Solanum tuberosum L.): Phytochemical composition and inhibition of 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea induced breast cancer in rats. J Food Compos Anal 2009; 22: 571–576. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schieber A; Saldana MDA Potato peels: A source of nutritionally and pharmacologically interesting compounds-A review. Food 2008; 3: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Weshahy A; Rao VA, Potato peel as source of important phytochemical antioxidant nutraceuticals and their role in human health-A review In Phytochemicals as Nutraceuticals - Global Approaches to Their Role in Nutrition and Health, Rao V, Ed. InTech: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lulai EC, Wound Healing In Potato Biology and Biotechnology: Advances and Prespectives, First ed.; Verugdenhil H, Ed. Elsevier,The Netherlands: 2007; pp 472–500. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyselka J; Bleha R; Dragoun M, et al. Antifungal polyamides of hydroxycinnamic acids from sunflower bee pollen. J Agric Food Chem 2018; 66: 11018–11026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dastmalchi K; Perez-Rodriguez M; Lin J, et al. Temporal resistance of potato tubers: Antibacterial assays and metabolite profiling of wound healing tissue extracts from contrasting cultivars. Phytochemistry 2019; 159: 75–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dastmalchi K; Wang I; Stark RE Potato wound-healing tissues: A rich source of natural antioxidant molecules for food preservation. Food Chem. 2016; 210: 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrews JM Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001; 48: 5–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner H; Ulrich-Merzenich G Synergy research: approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine 2009; 16: 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K; Rossi PG; Ferrari B, et al. Composition, irregular terpenoids, chemical variability and antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Santolina corsica Jordan et Fourr. Phytochemistry 2007; 68: 1698–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ren Y; Shen L; Zhang DW, et al. Two new sequisterpenoids from Solanum lyratum with cytotoxic activities. Chem Pharm Bull 2009; 57: 408–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ismail S; Jalilian FA; Talebpour AH, et al. Chemical composition and antibacterial and cytotoxic activities of Allium hirtifolium Bioss. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 696835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman M Chemistry, biochemistry and dietary role of potato polyphenols, A review. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1997; 47: 1523–1540. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DB; Roddick JG; Jones JL Synergism between the potato glycoalkaloids α-chaconine and α-solanine in inhibition of snail feeding. Phytochemistry 2001; 57: 229–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borges A; Abreu AC; Dias C, et al. New prespectives on the use of phytochemicals as an emergent strategy to control bacterial infections including biofilms. Molecules 2016; 21: 877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanchez-Maldonado AF; Schieber A; Ganzel MG Antifungal activity of secondary plant metabolites from potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.): Glycoalklaoids and phenolic acids show synergistic effects. J. Appl. Microbiol 2016; 120: 955–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hemaiswarya S; Doble M Synergistic interaction of phenylporpanoids with antibiotics against bacteria. J Med Microbiol 2010; 59: 1469–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fadl Almoula N; Voynikonv Y; Gevrenova R, et al. Antibacterial, antiproliferative and antioxidant activity of leaf extracts of selected Solanaceae species. S Afr J Bot 2017; 112: 368–374. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gai YP; Han XJ; Li YQ, et al. Metabolomic analysis reveals the pontential metabolites and pathogenesis involved in mulberry yellow dwarf disease. Plant Cell Environ 2014; 37: 1474–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos MM; Vieira-da-Motta O; Vieira IJ, et al. Antibacterial activity of Capsicum annum extract and synthetic capsaicinoid derivative against Streptococcus mutans. J Natural Medicines 2012; 66: 354–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.