Abstract

Purpose

Our institution cancelled all in-person clerkships owing to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. In response, we designed a virtual radiation oncology medical student clerkship.

Methods and Materials

We convened an advisory panel to design a virtual clerkship curriculum. We implemented clerkship activities using a cloud-based learning management system, video web conferencing systems, and a telemedicine portal. Students completed assessments pre- and postclerkship to provide data to improve future versions of the clerkship.

Results

The virtual clerkship spans 2 weeks and is graded pass or fail. Students attend interactive didactic sessions during the first week and participate in virtual clinic and give talks to the department during the second week. Didactic sessions include lectures, case-based discussions, treatment planning seminars, and material adapted from the Radiation Oncology Education Collaborative Study Group curriculum. Students also attend virtual departmental quality assurance rounds, cancer center seminars, and multidisciplinary tumor boards. The enrollment cap was met during the first virtual clerkship period (April 27 through May 8, 2020), with a total of 12 students enrolling.

Conclusions

Our virtual clerkship can increase student exposure and engagement in radiation oncology. Data on clerkship outcomes are forthcoming.

Introduction

On March 15, 2020, Stanford School of Medicine, with the guidance from the Association of American Medical Colleges, suspended all on-site clinical clerkships because of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. To provide alternative clinical learning opportunities, we created a virtual radiation oncology clerkship for Stanford medical students.

We aimed to fulfill the learning objectives of an in-person rotation in our department by leveraging a broad array of e-learning tools. We report here our experience with designing and implementing this virtual clerkship.

Methods and Materials

We convened an advisory panel of key stakeholders, including the medical student clerkship director (Stanford), the residency program leadership (Stanford), the associate dean of medical school admissions (Stanford), the medical student clerkship coordinator (Stanford), and other faculty and residents interested in medical education (remaining authors). The panel met weekly during the design phase to create course objectives and curriculum.

Canvas (www.instructure.com), Stanford’s primary cloud-based learning management system, hosts the clerkship and provides the integrated calendaring and syllabus system, communication stream, built-in web conferencing functionality, and assignment modules. Synchronous didactic sessions, chart rounds, and tumor boards are held using Zoom or WebEx, commercially available video web conferencing systems. Virtual clinic visits are facilitated via a secure cloud-based telemedicine portal using Epic Systems, which allows remote multiparty connections.

The panel continues to meet weekly during the implementation phase of the clerkship to troubleshoot issues that arise. In addition, students are required to submit anonymized pre- and postclerkship assessments to provide data to improve future versions of this clerkship.

Results

Students attend didactic sessions led by faculty, residents, and dosimetrists during the first week of the clerkship. During the second week, students participate in virtual clinics and give talks to the department (Table 1 and Fig 1).

Table 1.

Sample student schedule for 2-week radiation oncology clerkship

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1: Lecture block | 8:00-8:30 AM Orientation to the clerkship (FAC) 8:30-9:00 AM History of radiation oncology (FAC) 9:00-10:00 AM Introduction to radiation oncology (RES) 1:00-2:00 PM Introduction to radiation physics (RES) |

8:00-9:00 AM Cancer center seminar∗ or pediatric tumor board 10:00-11:00 AM Introduction to radiation for breast cancer (FAC) 11:00 AM to 12:00 PM Radiation treatment planning (FAC and dosimetrist) 2:00-3:00 PM Thoracic tumor board |

7:30-10:30 AM Resident education† 10:30-11:30 AM Approach to clinic notes (FAC) 1:00-2:00 PM Virtual department tour (RES) 3:30-5:00 PM GI tumor board |

7:30-8:30 AM Chart rounds‡ 1:00-2:00 AM Basics of prostate cancer/brachytherapy (FAC) 4:30-6:00 PM Head and neck tumor board |

8:00-9:00 AM Resident education† 9:00-10:00 AM Head and neck cancer and treatment planning (FAC) 10:30-11:30 AM CyberKnife treatment planning (FAC) 1:00-2:00 PM CNS tumor board |

| Week 2:Virtual clinic and student talks | Virtual clinic§ 8:00-9:00 AM Lymphoma tumor board |

Virtual clinic§ 8:00-9:00 AM Cancer center seminar∗ or pediatric tumor board 2:00-3:00 PM Thoracic tumor board |

Virtual clinic§ 7:30-10:30 AM Resident education† 3:30-5:00 PM GI tumor board |

Virtual clinic§ 7:30-8:30 AM Chart rounds‡ 8:30-9:30 AM Journal club student talks 4:30-6:00 PM Head and neck tumor board |

Virtual clinic§ 8:00-9:00 AM Resident education† 8:30-9:30 AM Journal club student talks 1:00-2:00 PM CNS tumor board |

Abbreviations: CNS = central nervous system; FAC = faculty-led; GI = gastrointestinal; RES = resident-led.

Weekly seminar on an oncology topic given by faculty speakers from various departments in the cancer center.

Scheduled didactics for residents; these are lectures on various disease-sites and radiation topics led either by faculty or residents.

Chart rounds are weekly department quality assurance sessions where new patients’ radiation treatment plans are reviewed.

Virtual clinic hours and days varied based on assigned faculty’s clinical schedule.

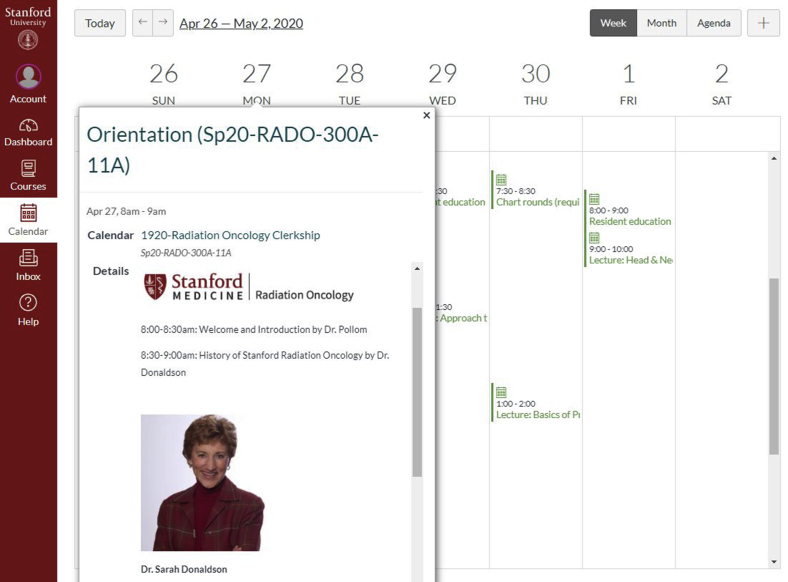

Figure 1.

Front-end student view of virtual clerkship schedule on the Canvas web application. Students can directly access Zoom lectures and assignments using this interface.

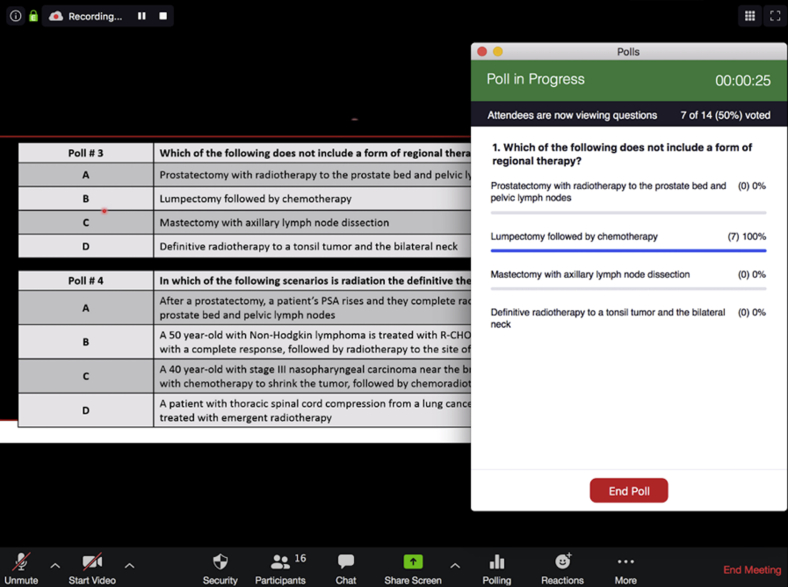

Didactic sessions include lectures, case-based discussions, treatment planning sessions in Eclipse and Precision, and lectures adapted from the Radiation Oncology Education Collaborative Study Group curriculum material.1 Faculty and resident speakers are encouraged to integrate Zoom features such as polling (Fig 2) and chat into their sessions to engage students. A resident moderator cohosts every session to help answer chat questions while the primary speaker leads the session. The sessions are password protected, require attendee registration to track attendance, and are recorded so that students can review the material later. In addition, medical students attend departmental quality assurance rounds, cancer center seminars, and multidisciplinary tumor boards that do not conflict with clerkship activities, which are all currently offered in a virtual environment.

Figure 2.

Poll feature on the Zoom platform allows students to answer questions in real-time during synchronous didactic sessions.

For the virtual clinic experience, students are assigned to different services in teams of 2. Students work with the resident and faculty of their assigned service to see and present virtual clinic patients during the second week of the clerkship.

At the end of the clerkship, students give a virtual journal club talk to the department on a recently published oncology paper. Table 2 shows course objectives and requirements. The clerkship is graded on a pass or fail basis.

Table 2.

Course objectives and requirements

| Course objectives |

|

| Course requirements |

|

The enrollment cap was met during the first virtual clerkship period (April 27 through May 8, 2020), with a total of 12 students enrolling. Table 3 shows demographics and preclerkship self-assessment responses of the first cohort. Over half of the cohort (58%) was female. Only 1 student had prior exposure to radiation oncology.

Table 3.

Preclerkship assessment responses of first virtual clerkship student cohort (total n = 12)

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 27 (23-31) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 7 (58.3%) |

| Male | 5 (41.7%) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 4 (33.3%) |

| Caucasian | 6 (50.1%) |

| Black or African American | 1 (8.3%) |

| Latino, or of Spanish origin | 1 (8.3%) |

| Clinical experience | |

| First clinical year | 12 (100%) |

| Second clinical year | - |

| Degree track | |

| MD | 8 (66.7%) |

| MD/PhD | 3 (25%) |

| Other | 1 (8.3%) |

| First radiation oncology rotation | 12 (100%) |

| Had prior exposure to radiation oncology | 1 (8.3%) |

| Current interest in radiation oncology | |

| Not interested at all | 1 (8.3%) |

| Would consider oncology but not necessarily radiation oncology | 3 (25%) |

| Considering learning more about radiation oncology | 8 (66.7%) |

| Considering applying to radiation oncology residency | - |

| Likely to apply to radiation oncology residency | - |

| Understands daily responsibilities of a radiation oncologist | |

| Strongly disagree | 3 (25%) |

| Disagree | 8 (66.7%) |

| Neutral | 1 (8.3%) |

| Agree | - |

| Strongly agree | - |

| Motivations for enrolling in virtual clerkship | |

| Interest in radiation oncology | 7 (58.3%) |

| Interest in learning with new technologies | 7 (58.3%) |

| COVID-19 restrictions | 12 (100%) |

Abbreviation: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Discussion

We radically restructured our medical student clerkship program owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. To allow medical students to maximize their educational opportunities during these uncertain times, we created a virtual radiation oncology clerkship.

Medical students receive little exposure to radiation therapy although it is a key component of multidisciplinary cancer care. Of the approximately 90 medical students per graduating class at Stanford, only 4 Stanford medical students have rotated through our department from July 2018 to March 2020. Our virtual clerkship generated much more interest, with the enrollment cap met almost immediately after the course was offered. Given the paucity of competing in-person clerkships and limited choices, students taking our clerkship may not have the same level of interest in radiation oncology as prior rotating students who selected our clerkship. However, 67% of the cohort did express interest in “learning more about radiation oncology,” with 92% having had no prior exposure to radiation oncology. Further, over half were women. This virtual clerkship broadened our reach, providing an important opportunity to address female trainee underrepresentation and declining overall numbers of applicants in radiation oncology.2,3

We included in our virtual clerkship educational activities that medical students have previously ranked as important and are key components of our 4-week in-person clerkship. These included structured didactics, treatment planning sessions, and the opportunity to (virtually) see and present clinic patients and give a formal talk.4, 5, 6 Because our virtual clerkship can accommodate more students than an in-person clerkship, we divided the students into smaller teams assigned to specific services to preserve the important interpersonal components of an in-person clerkship.

Our virtual clerkship is currently offered through the end of June. We plan to present full results, with student and faculty feedback of the educational value of the clerkship, after several cohorts complete the clerkship. We will also examine how this clerkship ultimately affects recruitment to our specialty. Future efforts will focus on allowing students from other institutions to take the virtual clerkship. Having this option can increase access for students who may not be able to pursue an away rotation at our institution.7

COVID-19 has challenged us to adapt and innovate quickly in our daily work, which includes the education of our trainees. Our virtual clerkship can facilitate the integration of radiation oncology education into the medical student curriculum and increase student exposure to our field and interest in radiation oncology as a career.

Acknowledgments

We thank the residents and faculty of the Stanford department of radiation oncology for helping with virtual clinic and didactic sessions.

Footnotes

Sources of support: This work had no specific funding.

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.Golden D.W., Braunstein S., Jimenez R.B. Multi-institutional implementation and evaluation of a curriculum for the medical student clerkship in radiation oncology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed A.A., Hwang W.-T., Holliday E.B. Female representation in the academic oncology physician workforce: Radiation oncology losing ground to hematology oncology. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2017;98:31–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.01.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates J.E., Amdur R.J., Lee W.R. The high number of unfilled positions in the 2019 radiation oncology residency match: Temporary variation or indicator of important change? Pract Radiat Oncol. 2019;9:300–302. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Golden D.W., Raleigh D.R., Chmura S.J., Koshy M., Howard A.R. Radiation oncology fourth-year medical student clerkships: A targeted needs assessment. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2013;85:296–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ni L., Chmura S.J., Golden D.W. National radiation oncology medical student clerkship trends from 2013 to 2018. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2019;104:24–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jagadeesan V.S., Raleigh D.R., Koshy M., Howard A.R., Chmura S.J., Golden D.W. A national radiation oncology medical student clerkship survey: Didactic curricular components increase confidence in clinical competency. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2014;88:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.11.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidiqi BU, Gillespie EF, Lapen K, Tsai CJ, Dawson M, Wu AJ. Patterns and perceptions of “away” rotations among radiation oncology residency applicants. Int J Radiat Oncol.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]