Abstract

Background:

Conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy offers minor benefit to patients with mucosal melanoma (MM). Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have become the preferred approach in patients with advanced or metastatic cutaneous melanoma, the evidence of their clinical use for MM is still limited. This systematic review aims to summarize the efficacy and safety of ICIs in advanced or metastatic MM.

Methods:

We searched electronic databases, conference abstracts, clinical trial registers and reference lists for relevant studies. The primary outcomes included the overall response rate (ORR), median progression-free survival (PFS), median overall survival (OS), one-year PFS rate, and one-year OS rate.

Results:

This review identified 13 studies assessing anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy, 22 studies assessing anti-PD-1 monotherapy, two studies assessing anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 combination therapy, one study assessing anti-PD-1 antibodies combined with axitinib, and three studies assessing anti-PD-1 antibodies combined with radiotherapy. For most patients who received ipilimumab monotherapy, the ORR ranged from 0% to 17%, the median PFS was less than 5 months, and the median OS was less than 10 months. For patients who received nivolumab or pembrolizumab monotherapy, most studies showed an ORR of more than 15% and a median OS of more than 11 months. The combined administration of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 agents showed benefits over single-agent therapy with an ORR of more than 33.3%. In a phase Ib trial of toripalimab in combination with axitinib, approximately half of patients had complete or partial responses. Three retrospective studies that investigated anti-PD-1 antibodies combined with radiotherapy showed an ORR of more than 50%, which was higher than each single modality treatment.

Conclusions:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, especially anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies alone and in combination with anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies or other modalities, are promising treatment options for advanced or metastatic MM. However, high-level evidence is still needed to support the clinical application.

Keywords: mucosal melanoma, immune checkpoint inhibitor, CTLA-4, PD-1, radiotherapy

Background

Mucosal melanoma (MM) is a rare malignancy, accounting for approximately 1% of all melanoma subtypes in the United States.1 However, more than 20% of patients with melanoma in Asia belong to this rare subtype, which is the second most common subtype.2 Although surgical excision is the primary treatment choice for early MM, most patients with MM are diagnosed at an advanced or metastatic stage because of the initial absence of symptoms and lack of visibility.3 In addition, it is difficult to obtain a complete resection with negative margins due to complicated anatomy common to MM; most patients will ultimately develop metastatic disease.4–6 Therefore, systemic treatment for MM is essential.

Unfortunately, due to the rarity of MM, there are few clinical trials evaluating optimal interventions in MM and the systemic treatment options for this disease are extremely limited. Patients with MM are often treated with the same regimen used for cutaneous melanoma, although some previous research has suggested that MM has distinct clinical and genetic characteristics and the same regimen used for cutaneous disease might be less effective in patients with MM.7–9 Poor outcomes have been reported with cytotoxic chemotherapies for MM, and there remains a high unmet need for effective systemic treatments for this subtype.

Although a better understanding of the molecular characteristics of MM has led to the development of targeted therapies in recent years, driver gene mutations occur at a low rate and most patients do not receive enduring benefits from these treatments.10–14 Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are a revolutionary breakthrough and have become a preferred first-line approach for most patients with advanced or metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Compared with cytotoxic chemotherapy, single or combined ICI therapy could offer strong survival benefits for patients with advanced or metastatic cutaneous melanoma.15 Therefore, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved three ICIs for the treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic melanoma: a monoclonal antibody anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) ipilimumab; two monoclonal antibodies anti-programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) pembrolizumab and nivolumab; as well as the combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab. However, given the low incidence of MM, few patients with MM were involved in previous clinical trials and most patients with MM were not reported separately from these clinical trials accruing patients with general melanoma type. Consequently, little is known about the efficacy and safety of ICIs in routine clinical application for MM. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to summarize the efficacy and safety of ICIs in advanced or metastatic MM.

Methods

The protocol for this systematic review was registered in Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 21 August 2019 (ID: CRD42019129009). This review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.16

Literature search

Considering that MM is a rare disease, we aimed to identify all prospective or retrospective studies of advanced or metastatic patients with MM who were treated with ICIs. Single case reports were excluded. Language was restricted to English and Chinese.

We searched four electronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) to identify all relevant records (from 1 January 1990 to 23 February 2020). In addition, we conducted a hand search of conference abstracts and clinical trial registers for relevant records. The search strategies are shown in Supplemental Appendix 1. Reference lists of included studies and review articles were also checked.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (JL, HK) independently screened the titles and abstracts of records that were identified from electronic databases. For records that were considered potentially relevant according to titles and abstracts, full text was obtained to assess the eligibility of studies. One author (JL) conducted the hand search and assessed the eligibility of conference abstracts and clinical trial registers. An additional author (CB) arbitrated through discussion in the event of a disputed qualification. Data extraction was conducted independently and in duplicate by two authors (JL, HK). An additional author (CB) independently reviewed the extracted data and resolved possible disagreements. Two authors (JL, HK) used the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) scales to assess the methodological quality of each study (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools).

The primary outcomes included the objective response rate (ORR) determined by the sum of complete response (CR) and partial response (PR), median progression-free survival (PFS), median overall survival (OS), one-year PFS rate and one-year OS rate. Secondary outcomes included the incidence of all grades and grade 3 or more immune-related adverse events (irAEs) related to ICIs. The irAEs are graded by common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE).

Results

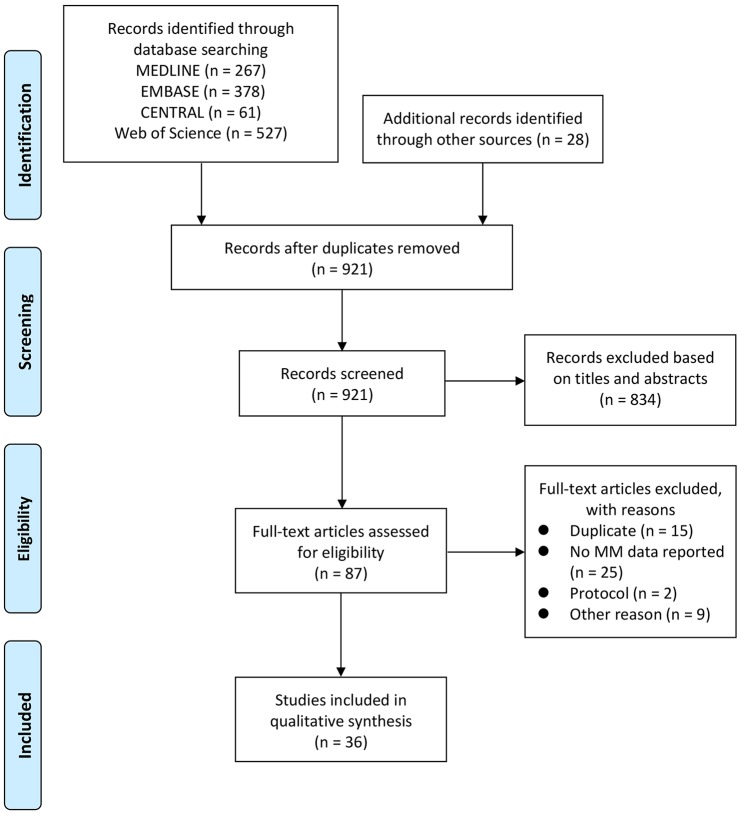

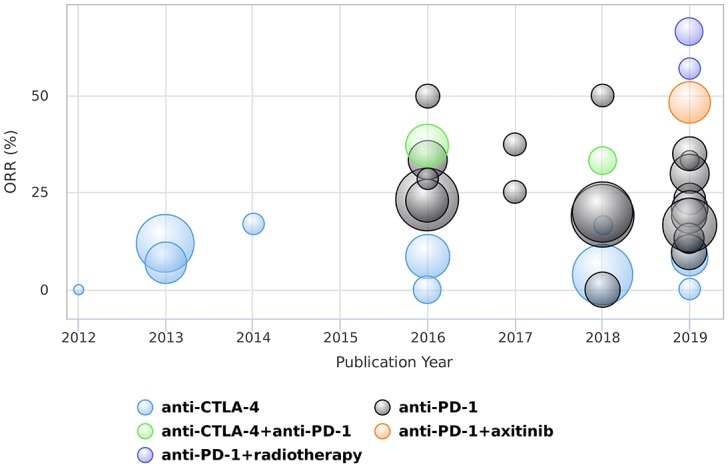

The initial literature search identified 1261 records. After removing duplicate studies and evaluating titles and abstracts by two reviewers, 87 potentially relevant studies were identified and retrieved for full-text screening. After full-text evaluation, 36 records were included in the qualitative synthesis (Figure 1). The characteristics of all included studies are presented in Table 1. The ORR outcomes of each individual study are also summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 41 studies included in the qualitative data synthesis.

| Study characteristics |

Primary outcomes |

Secondary outcomes |

Methodological quality | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Registration ID | Study design | Sample size | Location | Intervention (mg/kg) | Line of immunotherapy | ORR (%) | CR (%) | PR (%) | mPFS (months) | mOS (months) | 1-year PFS (%) | 1-year OS (%) | All grades irAEs (%) | Grade 3+ irAEs (%) | |

| D’Angelo et al.17 |

NCT01927419 NCT01844505 |

Pooled analysis of CheckMate 067 and CheckMate 069 | 36 | North America, Europe, Australia | Ipilimumab (3) | 1 | 8.3 (95% CI 1.8–22.5) | 0 | 8.3 | 2.7 (95% CI 2.6–2.8) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Good |

| Zimmer et al.18 | NCT01355120 | Open-label, multi-center, single-arm phase II study (DeCOG) | 7 | Germany | Ipilimumab (3) | 2/3 | 17 | 0 | 17 | NR | 9.6 (95% CI 1.6–11.1) | NR | 14 | 29 | 14 | Fair |

| Del Vecchio et al.19 | NR | Expanded Access Program | 71 | Italy | Ipilimumab (3) | 1/2/3 | 12 | 1 | 10 | 4.3 (95% CI 3.4–5.2) | 6.4 | 15 | 35 | 35 | 9 | Fair |

| Rapoport et al.20 | NR | Expanded Access Program | 12 | South Africa | Ipilimumab (3) | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | Fair |

| Shaw et al.21 | NR | Expanded Access Program | 4 | UK | Ipilimumab (3) | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Alexander et al.22 | NR | Named Patient Program | 8 | Australia | Ipilimumab (3) | 2+ | NR | NR | NR | 2.7 (95% CI 0.5–3.9) | 5.8 (95% CI 1.1–not reached) | 0 | 20 | NR | NR | Poor |

| Mignard et al.23 | NR | Multi-center, retrospective study | 76 | France | Ipilimumab (3) | 1/2 | 3.9 (95% CI 0.8–11.1) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 26.3 | Fair |

| Postow et al.24 | NR | Multi-center, retrospective study | 33 | USA | Ipilimumab (3/10) | 1/2/3/4 | 6.7 (95% CI 0.8–22.1) | 3.4 | 3.4 | NR | 6.4 | 10 | NR | 38 | 6 | Fair |

| Arzu Yasar et al.25 | NR | Multi-center, retrospective study | 11 | Turkey | Ipilimumab (NR) | 1/2/3+ | NR | NR | NR | NR | 6.9 (95% CI 4.5–9.3) | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Moya-Plana et al.26 | NR | Single-center, prospective study | 24 | France | Ipilimumab (3) | 1 | 8.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 3 (95% CI 2.5–4.6) | 12 (95% CI 5.9–26.9) | 8 | 54 | NR | 12.5 | Fair |

| Schaefer et al.27 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 8 | Germany | Ipilimumab (NR) | NR | 12.5 | 0 | 12.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Saijo et al.28 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 7 | Japan | Ipilimumab (3) | 2+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6.4 | 22 | 0 | NR | 100 | 71.4 | Poor |

| Quereux et al.29 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 6 | France | Ipilimumab (3) | 1/2 | 16.7 | 0 | 16.7 | NR | NR | 0 | 33 | 66.7 | 16.7 | Poor |

| Kiyohara et al.30 | NR | Ongoing, prospective, postmarketing surveillance observational study | 208 | Japan | Nivolumab (2) | 2/3/4+ | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.3 | NR | NR | 53.4 | NR | Poor |

| D’Angelo et al.17 |

NCT00730639 NCT01621490 NCT01721772 NCT01721746 NCT01844505 |

Pooled analysis of CA209-003, CA209-038, CheckMate 066, CheckMate 037, and CheckMate 067 | 86 | North America, Europe, Australia | Nivolumab (3) | 1/2+ | 23.3 (95% CI 14.8–33.6) | 5.8 | 17.4 | 3.0 (95% CI 2.2–not reached) | NR | 27 | NR | 66.3 | 8.1 | Fair |

| Nathan et al.31 | NCT02156804 | Single-arm, open-label, multi-center phase II study (CheckMate 172) | 63 | Europe | Nivolumab (3) | 2/3/4+ | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.5 (95% CI 6.4–15.0) | NR | 47.2 | 66.7 | 20.6 | Good |

| Nomura et al.32 | UMIN000015845 | Single-arm, open-label, multi-center phase II study | 17 | Japan | Nivolumab (2) | 1/2 | 23.5 (95% CI 6.8–49.9) | 5.9 | 17.6 | 1.4 (95% CI 1.2–2.8) | 12.0 (95% CI 3.5–not reached) | 17.6 | 50.0 | 70 | 15 | Good |

| Yamazaki et al.33 | JapicCTI-142533 | Single-arm, open-label, multi-center phase II study | 6 | Japan | Nivolumab (3) | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 33.3 | NR | 12 | 16.7 | 50 | NR | NR | Fair |

| Takahashi et al.34 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 27 | Japan | Nivolumab (2) | NR | 33.3 | 7.4 | 25.9 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Otsuka et al.35 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 27 | Japan | Nivolumab (2) | 1/2+ | 30 | 11 | 19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 59 | 11 | Poor |

| Maeda et al.36 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 24 | Japan | Nivolumab (NR) | NR | 20.8 | 0 | 20.8 | 7.5 | 14.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Kondo et al.37 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 22 | Japan | Nivolumab (2/3) | 1/2 | 9.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Fair |

| Koyama et al.38 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 21 | Japan | Nivolumab (NR) | 1 | 19 (95% CI 35–77) | NR | NR | 2.1 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 59 | 29 | 4.8 | Poor |

| Quereux et al.29 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 8 | France | Nivolumab (3) | 1/2 | 50 | 0 | 50 | 9 | NR | 0 | 86 | 100 | 0 | Poor |

| Urasaki et al.39 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 8 | Japan | Nivolumab (NR) | 2 | 37.5 | 25 | 12.5 | 10.2 | Not reached | NR | NR | 87.5 | 0 | Poor |

| Hamid et al.40 |

NCT01295827 NCT01704287 NCT01866319 |

Post-hoc analysis of KEYNOTE-001, 002, 006 | 84 | North America, Europe, Australia | Pembrolizumab (2) | 1/2/3/4+ | 19 (95% CI 11–29) | NR | NR | 2.8 (95% CI 2.7–2.8) | 11.3 (95% CI 7.7–16.6) | 0 | 45.2 | 73 | 10 | Good |

| Si et al.41 | NCT02821000 | Phase Ib study (KEYNOTE-151) | 15 | China | Pembrolizumab (2) | 2 | 13.3 (95% CI 1.7–40.5) | 6.7 | 6.7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Good |

| Yamazaki et al.42 | NCT02180061 | Phase Ib study (KEYNOTE-041) | 8 | Japan | Pembrolizumab (2) | 1/2/3 | 25.0 (95% CI 3.2–65.1) | 0 | 25 | 3.4 (95% CI 2.1–not reached) | Not reached | 25 | 51.4 | 100 | 50 | Good |

| Moya-Plana et al.26 | NR | Single-center, prospective study | 20 | France | Pembrolizumab (2) | 1 | 35 | 20 | 15 | 5 (95% CI 2.6–33.1) | 16.2 (95% CI 5.3–42.6) | 38 | 57 | NR | 5 | Fair |

| Mignard et al.23 | NR | Multi-center, retrospective study | 75 | France | Nivolumab (3) or Pembrolizumab (2) | 1/2 | 20 (95% CI 11.6–30.8) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 18.7 | Fair |

| Shoushtari et al.43 | NR | Multi-center, retrospective study | 35 | USA | Nivolumab (0.3–10) or Pembrolizumab (2/10) | 1/2+ | 23 (95% CI 10–40) | 0 | 23 | 3.9 | 12.4 | ~20 | NR | NR | NR | Fair |

| Ogata et al.44 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 59 | USA | Nivolumab (NR) or Pembrolizumab (NR) | 1/2+ | 16.7 | NR | NR | 3.0 | 20.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Tian et al.45 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 9 | USA | Nivolumab (NR) or Pembrolizumab (NR) | NR | 50 | 16.7 | 33.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Schaefer et al.27 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 7 | Germany | Nivolumab (NR) or Pembrolizumab (NR) | NR | 28.6 | 0 | 28.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Poor |

| Chi et al.46 | NCT03013101 | Multi-center, open-label, phase II study | 21 | China | Toripalimab (3) | 2/3/4/5+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | Fair |

| D’Angelo et al.17 |

NCT01927419 NCT01844505 |

Pooled analysis of CheckMate 067 and CheckMate 069 | 35 | North America, Europe, Australia | Ipilimumab (3) + Nivolumab (1) | 1 | 37.1 (95% CI 21.5–55.1) | 2.9 | 34.3 | 5.9 (95% CI 2.2–5.4) | NR | 32 | NR | 97.1 | 40 | Good |

| Namikawa et al.47 | JapicCTI-152869 | Single-arm, open-label, multi-center phase II study | 12 | Japan | Ipilimumab (3) + Nivolumab (1) | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 33.3 | Not reached | Not reached | 54.7 | 75 | NR | NR | Fair |

| Sheng et al.48 | NCT03086174 | Open-label, phase Ib study | 33 | China | Toripalimab (1/3) + Axitinib (5 mg) | 1/2 | 48.3 (95% CI 29.4–67.5) | 0 | 48.3 | 7.5 (95% CI 3.7–not reached) | >18 | 41.4 | 65.5 | 97.0 (treatment-related) | 39.4 (treatment-related) | Fair |

| Kim et al.49 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 12 | Korea | Pembrolizumab (2) + Radiotherapy (20–69 Gy) | 1/2+ | 66.7 | 8.3 | 58.3 | <6 | >36 | 0 | 100 | NR | NR | Poor |

| Hanaoka et al.50 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 10 | Japan | Nivolumab (3) or Pembrolizumab (2) + Radiotherapy (30–70 Gy) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7.4 | Not reached | 20 | 64.3 | NR | NR | Poor |

| Kato et al.51 | NR | Single-center, retrospective study | 7 | Japan | Nivolumab (2/3) or Pembrolizumab (2) + Radiotherapy (30–60+ Gy) | NR | 57.1 | 28.6 | 28.6 | NR | NR | 50 | NR | NR | 0 | Poor |

NR: not reported.

Figure 2.

Summary of the objective response rates of different treatments in patients with mucosal melanoma. Note that the bubble size indicates the sample size of each study.

Anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies

Ipilimumab was assessed in 13 studies with a total of 303 patients (Table 1).17–29 A pooled analysis of 36 patients with MM treated with ipilimumab monotherapy showed efficacy with an ORR of 23.3% and median PFS of 3.0 months.17 DeCOG was an open-label, multi-center, single-arm phase II study that included patients with melanoma irrespective of the primary melanoma location. Patients received up to four cycles of ipilimumab that were administered at a dose of 3 mg/kg at 3-week intervals. None achieved a CR and the ORR of seven patients with MM was 17%. The median OS was 9.6 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.6–11.1) and the one-year OS rate was 14%. Evidence of the antitumor activity of ipilimumab in patients with MM was also observed in three expanded access program and one named patient program studies in Italy,19 South Africa,20 the UK,21 and Australia.22 Patients with unresectable stage III or IV disease were treated with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for up to four cycles, and the ORR ranged from 0% to 12%. A multicenter retrospective study was performed in the dermatology departments of 25 hospitals in France, where 76 patients with MM received ipilimumab and three patients responded with an ORR of 3.9% (95% CI 0.8–11.1%).23 In a multicenter, retrospective analysis of 33 patients with unresectable or metastatic MM treated with ipilimumab at a dose of 3 or 10 mg/kg, one immune-related CR, one immune-related PR, six immune-related stable disease, and 22 immune-related progressive disease cases were observed at approximately 12 weeks after initiation of therapy.24 A multicenter retrospective study included 11 patients with MM receiving ipilimumab at seven different medical oncology departments in Turkey and the median OS was 6.9 months (95% CI 4.5–9.3).25 A single-center, prospective cohort analyzed 24 patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic MM who received ipilimumab.26 The ORR was 8.2% with a median PFS of 5 months (95% CI 2.6–33.1) and a median OS of 16.2 months (95% CI 5.3–42.6). In addition, three single-center retrospective studies showed an ORR from 0% to 16.7% in MM patients who received ipilimumab monotherapy.27–29

Anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies

Regarding anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, 22 studies with a total of 850 patients were identified (Table 1). Nivolumab was independently assessed in 12 studies.17,29–39 A post-marketing surveillance study is ongoing to evaluate nivolumab (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) for Japanese patients with melanoma from approximately 100 institutions since the nivolumab approval date (4 July 2014).30 In the interim analysis, the estimated median OS was 379 days in the overall population, and 340 days for MM. A pooled analysis of 86 patients with MM treated with nivolumab monotherapy from five clinical trials (CA209-003, CA209-038, CheckMate-037, CheckMate-066, and CheckMate-067) showed efficacy with an ORR of 23.3% and median PFS of 3.0 months.17 Compared with 49 patients with tumor PD-L1 expression <5%, 15 patients with PD-L1 expression ⩾5% had a higher ORR (53.3% versus 12.2%). In a phase II, single-arm, open-label, multicenter study (CheckMate 172), 63 patients with MM who progressed on or after ipilimumab were treated with nivolumab 3 mg/kg for up to 2 years until progression or unacceptable toxicity. The median OS was 11.5 months (95% CI 6.4–15.0) and the one-year OS rate was 47.2% (95% CI 33.3–59.9%).31 Grade 3 or 4 irAEs affected the gastrointestinal tract, liver and pulmonary system in 20.6% of patients. A phase II trial conducted in Japan analyzed 17 unresectable metastatic MM cases treated with nivolumab administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks.32 One patient achieved CR, three patients achieved PR, and six patients achieved stable disease, resulting in a disease control rate of 52.9% and an ORR of 23.5%. Another phase II study of nivolumab (3 mg/kg) was performed on 24 Japanese patients with untreated stage III/IV or recurrent melanoma.33 When analyzing melanoma subtypes, the ORR for six patients with MM was 33.3% and the median OS was 12 months. In addition, seven independent single-center, retrospective studies showed that MM patients treated with nivolumab had an ORR from 9.5% to 50.0% and a median PFS from 2.1 to 10.2 months.29,34–39

Pembrolizumab was independently assessed in four studies.26,40–42 An exploratory post hoc analysis of three randomized trials (KEYNOTE-001, KEYNOTE-002, and KEYNOTE-006) enrolled almost 1600 patients with stage III or IV melanoma.40 Among 84 (5%) patients with MM, treatment with pembrolizumab resulted in an ORR of 19% (95% CI 11–29%), a median PFS of 2.8 months and a median OS of 11.3 months. In an open-label, non-randomized, multicenter, phase Ib trial (KEYNOTE-151), Si et al. reported the efficacy of pembrolizumab in Chinese patients with MM.41 Fifteen patients received 2 mg/kg pembrolizumab every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles (approximately 2 years). One (6.7%) patient achieved CR, and one (6.7%) patient achieved PR with an ORR of 13.3% (95% CI 1.7–40.5%). Similarly, Japanese patients with advanced melanoma in KEYNOTE-041 were given pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for up to 2 years or until confirmed progression or unacceptable toxicity.42 Among the eight evaluable patients with MM, the confirmed ORR determined by central review was 25.0% (95% CI 3.2–65.1%), which was higher than the ORR in KEYNOTE-151. A single-center prospective cohort enrolled 20 patients with locally advanced or metastatic MM who received first-line pembrolizumab monotherapy.26 The ORR of first-line pembrolizumab therapy was 35% (including four CRs) and the median PFS was 5 months (95% CI 2.6–33.1). In addition, eight patients who received pembrolizumab after ipilimumab failure had an ORR of 12.5% with a median PFS of 8 months.

Five studies assessed anti-PD-1 agents but did not separate nivolumab or pembrolizumab apart.23,27,43–45 A multicenter retrospective study was performed in France, with 75 MM patients who received initial nivolumab (3 mg/kg) or pembrolizumab (2 mg/kg).23 Fifteen patients had tumor response corresponding to an ORR of 20% (95% CI 11.6–30.8%) and 14 patients had grade 3 or 4 irAEs. Moreover, an additional multicenter retrospective study conducted in the United States analyzed outcomes in 35 patients with metastatic MM who were treated with pembrolizumab or nivolumab.43 The ORR in the mucosal subgroup was 23% with a median PFS and OS of 3.9 and 12.4 months, respectively. Ogata et al. collected data of 59 MM patients who received pembrolizumab or nivolumab.44 The ORR was 16.7% and the median PFS and OS were 3.0 and 20.1 months, respectively. The University of Pittsburgh evaluated clinical and radiological data collected from nine patients with MM who received nivolumab or pembrolizumab.45 Among six evaluable patients with MM, one CR (16.7%) and two PRs (33.3%) were observed. In a retrospective analysis of seven MM patients who received nivolumab or pembrolizumab, only two patients showed responses of more than 240 days in duration and the remaining patients had progressive disease.27

Toripalimab, also known as JS001, is a recombinant humanized anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody that was assessed in one study. In a multi-center, open-label, phase II registration study, toripalimab was given at 3 mg/kg via intravenous infusion every 2 weeks until disease progression or intolerable toxicity.46 Among 21 evaluable patients with MM, no CR and PR were observed, but 42.1% of patients had stable disease.

Anti-CTLA-4 combined with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies

Two studies assessed ipilimumab plus nivolumab combination therapy (Table 1).17,47 A pooled analysis of CheckMate 067 and CheckMate 069 identified 35 patients treated with the combination of nivolumab plus ipilimumab.17 The combination therapy showed greater activity than monotherapy, with an ORR of 37.1% and a median PFS of 5.9 months. However, the incidence of grade 3 or 4 irAEs was 40.0%, and one drug-related death occurred. Patients with tumor PD-L1 expression ⩾5% had a higher ORR than patients with PD-L1 expression <5% (60% versus 33%). In a multicenter, single-arm study, treatment-naive Japanese patients with different types of unresectable or recurrent melanoma received nivolumab (1 mg/kg) combined with ipilimumab (3 mg/kg) every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by biweekly doses of nivolumab (3 mg/kg).47 The ORR was 33.3% and the one-year survival rate was 75%, while the median OS and median PFS were not reached.

Anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies combined with axitinib

A single-center, phase Ib trial evaluated the safety and preliminary efficacy of toripalimab in combination with the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor inhibitor axitinib in patients with advanced MM (Table 1).48 Patients received toripalimab (1 or 3 mg/kg) every 2 weeks, in combination with axitinib (5 mg) twice a day. Among 29 patients with systemic treatment-naive MM, no patient had CR, but 14 patients had PR for an ORR of 48.3%. The median PFS was 7.5 months (95% CI 3.7 to not reached), and the median OS was still not reached after 18 months of follow-up. Most treatment-related AEs were grade 1 or 2, including diarrhea, proteinuria, hand and foot syndrome, fatigue, abnormal liver function, hypertension, abnormal thyroid function, and rash. Grade 3 or greater treatment-related AEs occurred in 13 patients (39.4%), and there was no treatment-related death. In addition, Sheng et al. evaluated the predictive values of tumor PD-L1 expression, tumor mutation burden (TMB), and inflammation and angiogenesis expression signatures in this trial.48 Patients with PD-L1-positive tumor (70.0% versus 42.1%, p = 0.25) and higher TMB (83.3% versus 45.5%, p = 0.17) had a better ORR, but the difference was not statistically significant. Compared with PD-L1-negative patients, patients with PD-L1-positive tumor had a statistically significant longer PFS (hazard ratio 0.38; 95% CI 0.14–1.00; p = 0.049). Responders also had statistically significant higher messenger RNA inflammation and angiogenesis signature scores than non-responders (p < 0.001).

Anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies combined with radiotherapy

The combination of anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies and radiotherapy was assessed in three studies (Table 1).49–51 One retrospective study in South Korea showed that pembrolizumab combined with radiotherapy offers a one-year target lesion control rate of 94.1%, which was significantly higher than that of the radiotherapy alone group (57.1%) and pembrolizumab alone group (25%).49 Compared with the radiotherapy alone group, the treatment-related AEs were not significantly increased and no grade 3 or more AEs occurred in the multimodal therapy group. Hanaoka et al. retrospectively investigated ten cases of MM treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab and radiotherapy. The local control rate of the primary lesion and regional lymph nodes was 100% with a median PFS of 7.4 months.50 Another retrospective study reported the efficacy and safety of combined radiotherapy and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies for MM.51 Four of the seven patients with MM achieved CR and PR (ORR = 57.1%) and grade 3 or more severe AEs were not observed.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we identified 41 studies with 1262 patients and offered an overview of the efficacy and safety of ICIs in advanced or metastatic MM. Although there was no randomized clinical trial specifically assessing ICIs in patients with MM, these agents still demonstrated meaningful clinical activity.

From this review, the data from the included studies suggest that MM is minimally susceptible to CTLA-4 blockade. The ORRs for ipilimumab monotherapy at a dose of 3 mg/kg ranged from 0% to 17% (Table 1, Figure 2). In line with the poor outcome, most records showed that the median PFS was less than 5 months and the median OS was less than 10 months. Moreover, four studies showed that grade 3 or more irAEs occurred at a frequency of more than 16% in patients treated with ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg. Although these studies were limited by their retrospective nature, they still indicated that the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab lacked enough efficacy but maintained toxicity in advanced or metastatic MM and did not support the use of ipilimumab monotherapy.

Monoclonal antibodies targeting the PD-1 and PD-L1 interaction seemed to be more effective than targeting CTLA-4 in the treatment of MM (Figure 2). Here, we identified 22 studies on anti-PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy, including nivolumab, pembrolizumab and toripalimab. The majority of studies showed an ORR of more than 15% and a median OS of more than 11 months. In addition, less than 20% of patients experienced grade 3 or more irAEs. These results suggested that anti-PD-1 antibodies could prolong survival with acceptable toxicity in patients with advanced or metastatic MM. However, high-level evidence of anti-PD-1 antibodies in patients with MM is still lacking, and the efficacy and safety need to be verified via randomized controlled trials in the future.

Previous data from cutaneous melanoma suggested that combined administration of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies had benefits over single-agent therapy but was associated with increased toxicity.15,52 Although directly comparative OS data between single-agent and combination strategies in patients with MM were lacking, there was a trend that combination therapy resulted in improved response rates (Figure 2). A pooled analysis identified an ORR of 37.1% and a median PFS of 5.9 months by administering ipilimumab plus nivolumab, which suggested that such a combination might provide a greater outcome in patients with MM than either agent alone.17 However, the incidence of grade 3 or 4 irAEs with combination therapy was 40.0%, and one treatment-related death was reported in this pooled analysis.

In melanoma, VEGF is often overexpressed and seems to play a critical role in disease progression.53 Therefore, VEGF-targeted anti-angiogenesis is a reasonable strategy in melanoma treatment. In this review, a phase II trial showed that 21 patients with MM receiving toripalimab single-agent treatment did not achieve any radiological response.46 However, in a single-center phase Ib trial of toripalimab in combination with the VEGF receptor inhibitor axitinib, approximately half of patients had CR or PR, which indicated that such a combination had promising antitumor activity.48 This study was a single-arm design and had a relatively small sample size, and a randomized, controlled, multi-center phase III trial is recruiting patients to validate the efficacy of this combination therapy (NCT03941795).

Because of the extraordinary progress of targeted therapy and ICIs and the low sensitivity of melanoma to radiation, radiotherapy is only reserved for palliative treatment in patients who cannot obtain a good response to systemic treatment. However, several studies have reported a meaningful synergetic effect of combining radiotherapy with ICIs in advanced cutaneous melanoma.54,55 In this review, we identified three single-center, retrospective studies that investigated radiotherapy combined with anti-PD-1 antibody.49–51 The ORRs of the multimodal therapy were more than 50%, which were much higher than each single modality treatment. In addition, no grade 3 or more AEs occurred in patients receiving multimodal therapy. These studies showed the attractive potential for synergy with the combination of anti-PD-1 ICIs and radiotherapy, and several prospective trials are ongoing to explore this combination further in the clinical setting (NCT03758729; ChiCTR1800019573; UMIN000030533).

Some studies included in this review suggested that the efficacy outcome of ICIs was poorer in MM compared with that in cutaneous melanoma, although no formal comparisons were made between subtypes.17 For instance, a pooled analysis of six clinical trials found that among patients treated with nivolumab monotherapy, MM had lower ORR (23.3% versus 40.9%) and shorter median PFS (3.0 months versus 6.2 months) than cutaneous melanoma.17 Moreover, among patients treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab combination therapy, lower ORR (37.1% versus 60.4%) and shorter median PFS (5.9 months versus 11.7 months) were also observed in MM. The exact reason for the less active response in MM remains unclear, yet a few studies have discovered some distinct biological characteristics of this rare subtype, which are likely to explain such a phenomenon. Common driver mutations identified in cutaneous melanoma, such as BRAF and NRAS, are less frequent in MM.56,57 In contrast, SF3B1 and KIT mutations occur more commonly in MM than in cutaneous melanoma. In addition, the anatomical distribution of MM precludes solar ultraviolet radiation as a major risk factor. In cutaneous melanoma, most mutations are ultraviolet radiation-induced C > T transitions at pyrimidine dimers, but MM lacks such a specific mutation pattern.58,59 Several recent genomic studies also demonstrate MM has a significantly lower TMB than other melanoma subtypes.56,59,60 Hayward et al. found cutaneous melanoma has one of the highest single-nucleotide variants and indel frequencies of any cancer with an average of 49.17 mutations per megabase, while MM only has an average of 1.95 mutations per megabase, a more than 25-fold lower TMB.56 TMB is an emerging, independent predictive biomarker that is associated with the probability of obtaining clinical benefit to immune checkpoint blockade in multiple tumor types.61,62 Tumors with a higher TMB may have more neoantigens, which make the immune system more likely to recognize the tumor as a foreign matter and remove it. Such a mechanism of TMB may contribute to the low immune response in this rare melanoma subtype.

PD-L1 is also a potential biomarker in predicting the response to ICIs.40,63,64 Some studies have demonstrated that MM has a lower PD-L1 expression than cutaneous melanoma.17,40,65 D’Angelo et al. found that compared with MM patients with tumor PD-L1 expression <5%, MM patients with tumor PD-L1 expression ⩾5% had higher ORRs when treated with nivolumab monotherapy (53.3% versus 12.2%) or ipilimumab plus nivolumab combination therapy (60.0% versus 33.3%).17 Notably, although cutaneous melanoma and MM had different tumor PD-L1 expression status, the ORRs were similar across treatment groups when we only focus on patients with tumor PD-L1 expression ⩾5%. Conversely, MM patients with tumor PD-L1 expression <5% exhibited a much poorer response than patients with cutaneous disease. The role of PD-L1 expression as a predictive biomarker in MM remains unclear and further studies are needed to clarify its usefulness.

This systematic review has several limitations. First, most studies included in this review were retrospective and had poor or fair methodological quality, and lack of high-quality clinical trials lead to potential biases. In addition, some data were derived from a pooled analysis of clinical trials recruiting patients with a general melanoma type, which indicated that the results should be interpreted with caution. Second, the information on prior treatment, especially systemic therapy, was not recorded in the majority of studies. The efficacy and safety of ICIs may be different in the first-line and further-line treatment of MM. Third, we did not collect the primary site information of MM, but it was reasonable that response to treatment might differ depending on the anatomical location. Finally, immune-RECIST (iRECIST) was only adopted in few studies to evaluate the response of MM, but this criterion was more reasonable in evaluating the response to ICIs, because ICIs occasionally have some non-traditional response patterns (e.g. pseudoprogression, hyperprogression) that did not occur in chemotherapy or targeted therapy.66

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review provides up-to-date evidence for the efficacy and safety of ICIs in advanced or metastatic MM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, especially anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies alone and in combination with anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies or other modalities, are promising treatment options for advanced or metastatic MM. However, high-quality evidence to support the clinical application is still limited, and the role of ICIs in patients with MM should be further clarified by randomized controlled trials that recruit specific patients with this orphan disease. We hope that this systematic review will open a new therapeutic window for patients with advanced or metastatic MM.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendix_A for Immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced or metastatic mucosal melanoma: a systematic review by Jiarui Li, Haoxuan Kan, Lin Zhao, Zhao Sun and Chunmei Bai in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr Li Xun for providing insightful suggestions about methodology of evidence-based medicine.

Footnotes

Author contributions: JL and CB conceived and designed the review. JL and HK conducted the literature search and collected the data. JL drafted the manuscript and figures. SZ, LZ, and CB reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 61435001) and the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (no. 2016-I2M-1-001, no. 2017-I2M-4-003)

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

ORCID iDs: Jiarui Li  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9340-3962

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9340-3962

Chunmei Bai  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1333-9145

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1333-9145

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Jiarui Li, Department of Medical Oncology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.

Haoxuan Kan, Department of Medical Oncology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.

Lin Zhao, Department of Medical Oncology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.

Zhao Sun, Department of Medical Oncology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.

Chunmei Bai, Department of Medical Oncology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, No.1 Shuai Fu Yuan, Dongcheng District, Beijing 100032, China.

References

- 1. Bishop KD, Olszewski AJ. Epidemiology and survival outcomes of ocular and mucosal melanomas: a population-based analysis. Int J Cancer 2014; 134: 2961–2971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chi Z, Li S, Sheng X, et al. Clinical presentation, histology, and prognoses of malignant melanoma in ethnic Chinese: a study of 522 consecutive cases. BMC Cancer 2011; 11: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guo J, Qin S, Liang J, et al. Chinese guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of melanoma (2015 edition). Ann Transl Med 2015; 3: 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carvajal RD, Spencer SA, Lydiatt W. Mucosal melanoma: a clinically and biologically unique disease entity. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012; 10: 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee SP, Shimizu KT, Tran LM, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the head and neck: the impact of local control on survival. Laryngoscope 1994; 104: 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lotem M, Anteby S, Peretz T, et al. Mucosal melanoma of the female genital tract is a multifocal disorder. Gynecol Oncol 2003; 88: 45–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seetharamu N, Ott PA, Pavlick AC. Mucosal melanomas: a case-based review of the literature. Oncologist 2010; 15: 772–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yi JH, Yi SY, Lee HR, et al. Dacarbazine-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment in noncutaneous metastatic melanoma: multicenter, retrospective analysis in Asia. Melanoma Res 2011; 21: 223–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bajetta E, Del Vecchio M, Bernard-Marty C, et al. Metastatic melanoma: chemotherapy. Semin Oncol 2002; 29: 427–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD, et al. KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. JAMA 2011; 305: 2327–2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, et al. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4340–4346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bai X, Mao LL, Chi ZH, et al. BRAF inhibitors: efficacious and tolerable in BRAF-mutant acral and mucosal melanoma. Neoplasma 2017; 64: 626–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified KIT arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3182–3190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 2904–2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pasquali S, Hadjinicolaou AV, Chiarion Sileni V, et al. Systemic treatments for metastatic cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 2: CD011123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D’Angelo SP, Larkin J, Sosman JA, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab alone or in combination with ipilimumab in patients with mucosal melanoma: a pooled analysis. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 226–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zimmer L, Eigentler TK, Kiecker F, et al. Open-label, multicenter, single-arm phase II DeCOG-study of ipilimumab in pretreated patients with different subtypes of metastatic melanoma. J Transl Med 2015; 13: 351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Del Vecchio M, Di Guardo L, Ascierto PA, et al. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab 3 mg/kg in patients with pretreated, metastatic, mucosal melanoma. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50: 121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rapoport BL, Vorobiof DA, Dreosti LM, et al. Ipilimumab in pretreated patients with advanced malignant melanoma: results of the South African expanded-access program. J Glob Oncol 2017; 3: 515–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shaw H, Larkin J, Corrie P, et al. Ipilimumab for advanced melanoma in an expanded access programme (EAP): ocular, mucosal and acral subtype UK experience. Ann Oncol 2012; 23 (Suppl. 9): 374–374.21536662 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alexander M, Mellor JD, McArthur G, et al. Ipilimumab in pretreated patients with unresectable or metastatic cutaneous, uveal and mucosal melanoma. Med J Aust 2014; 201: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mignard C, Deschamps Huvier A, Gillibert A, et al. Efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with metastatic mucosal or uveal melanoma. J Oncol 2018; 2018: 1908065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Postow MA, Luke JJ, Bluth MJ, et al. Ipilimumab for patients with advanced mucosal melanoma. Oncologist 2013; 18: 726–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arzu Yasar H, Turna H, Esin E, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with mucosal and ocular melanoma treated with ipilimumab: Turkish oncology group study. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2020; 26: 267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moya-Plana A, Herrera Gomez RG, Rossoni C, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of immunotherapy for non-resectable mucosal melanoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2019; 68: 1171–1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schaefer T, Satzger I, Gutzmer R. Clinics, prognosis and new therapeutic options in patients with mucosal melanoma: a retrospective analysis of 75 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96: e5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saijo K, Imai H, Ouchi K, et al. Therapeutic benefits of ipilimumab among Japanese patients with nivolumab-refractory mucosal melanoma: a case series study. Tohoku J Exp Med 2019; 248: 37–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Quereux G, Wylomanski S, Bouquin R, et al. Are checkpoint inhibitors a valuable option for metastatic or unresectable vulvar and vaginal melanomas? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: e39–e40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kiyohara Y, Uhara H, Ito Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in Japanese patients with malignant melanoma: an interim analysis of a postmarketing surveillance. J Dermatol 2018; 45: 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nathan P, Ascierto PA, Haanen J, et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with rare melanoma subtypes who progressed on or after ipilimumab treatment: a single-arm, open-label, phase II study (CheckMate 172). Eur J Cancer 2019; 119: 168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nomura M, Oze I, Masuishi T, et al. Multicenter prospective phase II trial of nivolumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic mucosal melanoma. Int J Clin Oncol. Epub ahead of print 14 January 2020. DOI: 10.1007/s10147-020-01618-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamazaki N, Kiyohara Y, Uhara H, et al. Long-term follow up of nivolumab in previously untreated Japanese patients with advanced or recurrent malignant melanoma. Cancer Sci 2019; 110: 1995–2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Takahashi A, Tsutsumida A, Namikawa K, et al. The efficacy of nivolumab for unresectable metastatic mucosal melanoma. Ann Oncol 2016; 27: 379–400.26681681 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Otsuka M, Sugihara S, Mori S, et al. Immune-related adverse events correlate with improved survival in patients with advanced mucosal melanoma treated with nivolumab: a single-center retrospective study in Japan. J Dermatol 2020; 47: 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Maeda T, Yoshino K, Nagai K, et al. Efficacy of nivolumab monotherapy against acral lentiginous melanoma and mucosal melanoma in Asian patients. Br J Dermatol 2019; 180: 1230–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kondo T, Nomura M, Otsuka A, et al. Predicting marker for early progression in unresectable melanoma treated with nivolumab. Int J Clin Oncol 2019; 24: 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koyama T, Kiyota N, Imamura Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab for non-cutaneous melanoma: a retrospective analysis from a single institution. Ann Oncol 2019; 30: vi91. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Urasaki T, Ono-Fuchiwaki M, Tomomatsu J, et al. Eight patients with mucosal malignant melanoma treated by nivolumab: a retrospective analysis in a single institution. Ann Oncol 2017; 28 (Suppl. 9): ix102–ix103. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hamid O, Robert C, Ribas A, et al. Antitumour activity of pembrolizumab in advanced mucosal melanoma: a post-hoc analysis of KEYNOTE-001, 002, 006. Br J Cancer 2018; 119: 670–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Si L, Zhang X, Shu Y, et al. A phase Ib study of pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for Chinese patients with advanced or metastatic melanoma (KEYNOTE-151). Transl Oncol 2019; 12: 828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yamazaki N, Takenouchi T, Fujimoto M, et al. Phase 1b study of pembrolizumab (MK-3475; anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody) in Japanese patients with advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-041). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2017; 79: 651–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shoushtari AN, Munhoz RR, Kuk D, et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 agents in acral and mucosal melanoma. Cancer 2016; 122: 3354–3362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ogata D, Haydu L, Glitza IC, et al. The efficacy of anti-PD-1 in metastatic acral and mucosal melanoma patients (pts). Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 2019; 33: 214. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tian L, Ding F, Sander C, et al. PD-1 blockade to treat mucosal and uveal melanoma: the University of Pittsburghh experience. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34 (Suppl. 15): e21042. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chi Z, Tang B, Sheng X, et al. A phase II study of JS001, a humanized PD-1 mAb, in patients with advanced melanoma in China. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 9539–9539. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Namikawa K, Kiyohara Y, Takenouchi T, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab in Japanese patients with advanced melanoma: an open-label, single-arm, multicentre phase II study. Eur J Cancer 2018; 105: 114–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sheng X, Yan X, Chi Z, et al. Axitinib in combination with toripalimab, a humanized immunoglobulin G4 monoclonal antibody against programmed cell death-1, in patients with metastatic mucosal melanoma: an open-label phase IB trial. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37: 2987–2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kim HJ, Chang JS, Roh MR, et al. Effect of radiotherapy combined with pembrolizumab on local tumor control in mucosal melanoma patients. Front Oncol 2019; 9: 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hanaoka Y, Tanemura A, Takafuji M, et al. Local and disease control for nasal melanoma treated with radiation and concomitant anti-programmed death 1 antibody. J Dermatol 2020; 47: 423–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kato J, Hida T, Someya M, et al. Efficacy of combined radiotherapy and anti-programmed death 1 therapy in acral and mucosal melanoma. J Dermatol 2019; 46: 328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1345–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gorski DH, Leal AD, Goydos JS. Differential expression of vascular endothelial growth factor-A isoforms at different stages of melanoma progression. J Am Coll Surg 2003; 197: 408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liniker E, Menzies AM, Kong BY, et al. Activity and safety of radiotherapy with anti-PD-1 drug therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncoimmunology 2016; 5: e1214788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Filippi AR, Fava P, Badellino S, et al. Radiotherapy and immune checkpoints inhibitors for advanced melanoma. Radiother Oncol 2016; 120: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hayward NK, Wilmott JS, Waddell N, et al. Whole-genome landscapes of major melanoma subtypes. Nature 2017; 545: 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nassar KW, Tan AC. The mutational landscape of mucosal melanoma. Semin Cancer Biol. Epub ahead of print 23 October 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pleasance ED, Cheetham RK, Stephens PJ, et al. A comprehensive catalogue of somatic mutations from a human cancer genome. Nature 2010; 463: 191–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Furney SJ, Turajlic S, Stamp G, et al. Genome sequencing of mucosal melanomas reveals that they are driven by distinct mechanisms from cutaneous melanoma. J Pathol 2013; 230: 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Newell F, Kong Y, Wilmott JS, et al. Whole-genome landscape of mucosal melanoma reveals diverse drivers and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun 2019; 10: 3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yarchoan M, Hopkins A, Jaffee EM. Tumor mutational burden and response rate to PD-1 inhibition. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 2500–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science 2018; 362: eaar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Havel JJ, Chowell D, Chan TA. The evolving landscape of biomarkers for checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2019; 19: 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Daud AI, Wolchok JD, Robert C, et al. Programmed death-ligand 1 expression and response to the anti-programmed death 1 antibody pembrolizumab in melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 4102–4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Nakamura Y, Ishitsuka Y, Tanaka R, et al. Acral lentiginous melanoma and mucosal melanoma expressed less programmed-death 1 ligand than cutaneous melanoma: a retrospective study of 73 Japanese melanoma patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: e424–e426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18: e143–e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendix_A for Immune checkpoint inhibitors in advanced or metastatic mucosal melanoma: a systematic review by Jiarui Li, Haoxuan Kan, Lin Zhao, Zhao Sun and Chunmei Bai in Therapeutic Advances in Medical Oncology