Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the prevalence and factors promoting caries in primary dentition of 3-5-year-old children in Northeast China.

Materials and Methods

Data of 1,229 children aged 3 to 5 years were randomly selected. The caries prevalence and other indicators were assessed, and the results analyzed by SPSS. A questionnaire was also given to the children's guardians to ascertain the potential risk factors associated with caries.

Results

The decayed, missing, and filled teeth (dmft) index in children aged 3, 4, and 5 years old was 3.17, 5.13, and 6.07, respectively, while the caries prevalence rate was 62.16%, 75.89%, and 87.28% accordingly. The incidence of caries among rural children was higher than that in urban areas. Regarding oral health awareness, it was found that parents in urban areas had more accurate perceptions of oral health problems. It was also noted that the children's brushing habits were worrying. Family economic and medical resources are not the main causes of serious dental caries in rural areas.

Conclusions

The oral health status of children aged 3-5 years is not optimistic. Many parents have a low awareness of oral health. Strengthening the promotion of oral health knowledge is an effective way to change the situation.

1. Background

Along with the constant improvement of the economy, children's oral hygiene has been brought to the forefront by parents as well as scholars in the largest developing country, China [1, 2]. Since the 1980s, three large-scale surveys of oral hygiene epidemiology have been conducted in China, in 1983, 1995, and 2005, respectively. These data offer great help in understanding the current situation of Chinese children's oral hygiene and their behavioral habits, while the data also provide scientific evidence for the government to formulate relevant health policies [3]. According to researches, in addition to physical health, children's oral hygiene is of the utmost importance in children's mental health as well as in interpersonal communication [4, 5].

Liaoning Province, situated in the northernmost area of China, is the only province that is both coastal and on the border. It has a land area of 1480 thousand square meters, occupying 1.5% of the total land area of China. At the end of 2017, the number of permanent residents was 43.689 million, of which the 0-to-15-year-old proportion of the population was 4.843 million, accounting for 11.09% of the permanent residents. The third national oral hygiene epidemiology survey, in 2005 [6], demonstrated that the caries prevalence rate of 5-year-old children in urban and rural areas of Liaoning Province was 64.3% and 83.6%, respectively, while the rates of dmft were 3.29- and 5.35-fold higher than the national average.

With the implementation of “the Revitalization of the Northeast” strategy over the past decade, the economy of Liaoning Province has been boosted. However, there appears to be no literature on the status of children's oral hygiene nor on the parents' understanding of the issue. The objectives of this study were (1) to record the prevalence of dental caries, (2) to investigate the degree of parents' attention to children's oral health, and (3) to compare the differences between urban and rural areas and the reasons for the differences between them.

2. Methods

2.1. Respondents

The respondents were permanent residents between the ages of 3 and 5 years old in rural and urban areas (having lived for more than six months at the place in question). Informed consent forms were signed by the children's guardians and were kept for record. The children received oral examinations by qualified dentists while parents received questionnaires and were interviewed by the same dentists. Ethical approval was received from the Institutional Review Board at the Chinese Stomatological Association (201502002).

2.2. Sampling Method

Multistage stratified sampling was adopted in the study. In the first stage, two districts (city) and two counties (town) were randomly selected in Liaoning Province according to population proportion sampling [7]. The results included Donggang City (county-level city/town), Heping District of Shenyang City (city), Linghe District of Shenyang City (city), and Zhuanghe City (county-level city/town). During the second stage, three kindergartens were randomly selected in each county (district), and for the third stage, using cluster sampling, 3-, 4-, and 5-year-old children were randomly selected from every kindergarten. The sampling capacity was estimated in accordance with the formula n = deff(uα2p(1 − p)/δ2). The design efficiency deff = 2.5, the level of confidence uα = 1.96, the margin of error δ = 10%, the expected caries prevalence rate was taken as 66%, based on the findings of the third national oral hygiene epidemiology survey in 2005 [6]. The number of samples for each kindergarten was calculated taking into account the stratification factors and nonresponse rate (estimated at 20%).

2.3. Training for Examination Personnel

All personnel had master's degrees or higher, as well as oral practitioner qualifications and more than three years' experience in oral clinic work. Before the on-site examination, both theoretical and clinical trainings were performed by the technical group responsible for the current fourth national oral hygiene epidemiology survey. Each examiner, together with a reference examiner, was requested to examine 10 to 15 respondents with the aim of assessing the consistency of their clinical examination. Consistency between examiners and reference examiners as well as consistency between examiners was monitored. The kappa value was from 0.8 to 0.89, which met the requirements of the examination. Three recorders were equipped with the necessary requirements. Questionnaire investigators were assessed after integrated training and were able to conduct questionnaires after qualification.

2.4. Standards and Contents of the Examination

An oral health survey was conducted with reference to the Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods (Fifth Edition) [8] recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Using an appropriate light source, the CPI probe was used to check the children's caries in a comprehensive manner. The questionnaire consisted of 3 parts: (1) oral health-related behaviors: tooth-brushing behavior, sugar intake, history, and experience of dental examinations; (2) family factors: parents' dental knowledge and attitude; and (3) medical treatment behavior: reasons for delaying treatment.

Data entry and analysis were done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS ver. 19.0). For enumeration data, the Pearson chi-squared test was adopted. For continuous data, the following test methods were used. Binary logistic regression was performed to investigate the effects of the independent variables on the children's dental caries and behaviors. The significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Statistics of Sampling Results

Using multistage stratified random sampling, a total of 1229 children between the ages of 3 and 5 years were enrolled in the study. These included 318 in Linghe District (urban), 324 in Heping District (urban), 284 in Zhuanghe City (rural), and 303 in Donggang City (rural). Among them, boys accounted for 51.1%, while girls accounted for 48.9%.

3.2. Caries Prevalence Rate and the Statistics of dmft

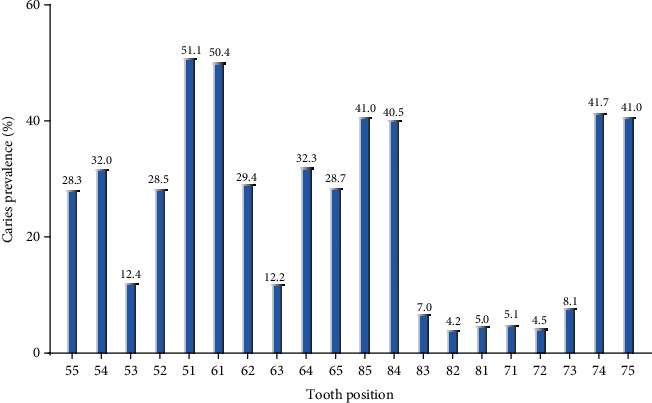

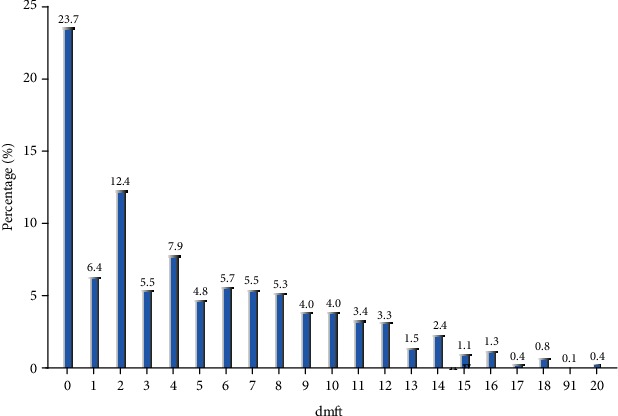

Overall, the dmft index of children aged 3, 4, and 5 years old was 3.17 ± 4.073, 5.13 ± 4.793, and 6.07 ± 4.718, respectively, with corresponding caries prevalence rates of 62.16%, 75.89%, and 87.28%, respectively. As people grow up, the caries prevalence rate also increases. There were statistically significant differences in caries prevalence rates between the different age brackets (P < 0.05). The incidence of caries among rural children was significantly higher than that in urban areas (P < 0.05), while no significant differences were observed between boys and girls at different ages (P > 0.05) (Table 1). In the 5-year-old children, the prevalence of caries in urban and rural areas was 81.0% and 94.0%, respectively. In terms of caries filling, it was found that 2,074 children have 6,074 decayed teeth among them in total, including 5,351 unfilled caries, 25 missing caries, and only 398 filled caries, accounting for 6.55%. Figure 1 shows the caries prevalence rate in different teeth of children aged 3 to 5 years old. The caries rate of the upper central incisor was the highest (51.08%) while the lower lateral incisor was the lowest (4.17%), and the rate of the lower mandible deciduous molar was higher than that of the upper mandible deciduous molar. In terms of the frequency of individual caries, 12.4% of children had two decayed teeth while children with four caries accounted for 7.9% (Figure 2). The caries were symmetrically distributed in the oral cavity in most cases.

Table 1.

Dental caries in children aged 3-5 years old.

| Age | N | dmft | Caries frequency | dt | mt | ft | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± Sd | t-value | P value | Percentage | χ 2 | P value | |||||

| 3 | ||||||||||

| Urban | 201 | 2.46 ± 3.712 | -3.856 | 0.000 | 53.7 | 15.323 | 0.000 | 2.35 ± 3.632 | 0.00 ± 0.000 | 0.11 ± 0.537 |

| Rural | 132 | 4.24 ± 4.367 | 75.0 | 4.17 ± 4.315 | 0.01 ± 0.087 | 0.06 ± 0.344 | ||||

| Male | 169 | 3.29 ± 4.316 | 0.553 | 0.580 | 60.4 | 0.476 | 0.490 | 3.17 ± 4.215 | 0.01 ± 0.077 | 0.11 ± 0.493 |

| Female | 164 | 3.04 ± 3.815 | 64.0 | 2.98 ± 3.800 | 0.00 ± 0.000 | 0.07 ± 0.445 | ||||

| Total | 333 | 3.17 ± 4.073 | 62.2 | 3.08 ± 4.011 | 0.00 ± 0.055 | 0.09 ± 0.470 | ||||

| 4 | ||||||||||

| Urban | 209 | 3.68 ± 4.244 | -6.284 | 0.000 | 64.1 | 29.705 | 0.000 | 3.23 ± 3.928 | 0.00 ± 0.069 | 0.45 ± 1.437 |

| Rural | 239 | 6.40 ± 4.894 | 86.2 | 6.23 ± 4.812 | 0.02 ± 0.129 | 0.15 ± 0.714 | ||||

| Male | 230 | 5.56 ± 4.792 | 1.953 | 0.051 | 79.1 | 2.708 | 0.100 | 5.18 ± 4.675 | 0.02 ± 0.131 | 0.36 ± 1.290 |

| Female | 218 | 4.68 ± 4.763 | 72.5 | 4.45 ± 4.633 | 0.00 ± 0.680 | 0.22 ± 0.904 | ||||

| Total | 448 | 5.13 ± 4.793 | 75.9 | 4.83 ± 4.664 | 0.01 ± 0.105 | 0.29 ± 1.120 | ||||

| 5 | ||||||||||

| Urban | 232 | 4.73 ± 4.206 | -6.528 | 0.000 | 81.0 | 16.886 | 0.000 | 4.03 ± 3.962 | 0.02 ± 0.185 | 0.68 ± 1.652 |

| Rural | 216 | 7.51 ± 4.820 | 94.0 | 7.07 ± 4.680 | 0.07 ± 0.347 | 0.37 ± 1.105 | ||||

| Male | 229 | 6.10 ± 4.782 | 0.133 | 0.894 | 85.6 | 1.201 | 0.273 | 5.54 ± 4.635 | 0.05 ± 0.306 | 0.51 ± 1.362 |

| Female | 219 | 6.04 ± 4.660 | 89.0 | 5.46 ± 4.527 | 0.03 ± 0.242 | 0.55 ± 1.484 | ||||

| Total | 448 | 6.07 ± 4.718 | 87.3 | 5.50 ± 4.578 | 0.04 ± 0.277 | 0.53 ± 1.422 | ||||

Figure 1.

The caries prevalence of each tooth of children aged 3 to 5 years old.

Figure 2.

The frequency distribution of dmft.

3.3. Results of Questionnaires

The questionnaire was divided into attitude towards oral health, oral health awareness, children's eating habits, tooth-brushing behavior, and children's medical treatment. In terms of attitude, most parents believed that both oral hygiene and regular examination are of utmost importance. In addition, there was no significant difference between urban and rural areas; 98.6% of parents in urban areas and 98.8% of parents in rural areas believed that oral health is important, while parents who thought that the mother's bad teeth could affect children accounted for 40.5% and 29.0% of respondents in urban and rural areas, respectively. In terms of the 6-year-olds, no significant statistical difference was found between the answers of parents from urban and rural areas (Table 2). Regarding oral health awareness, eight questions were raised, including whether the bleeding gums are normal when brushing teeth, whether bacteria lead to caries, and whether the decayed deciduous teeth require treatment. On the whole, accurate perceptions tend to be associated with parents in urban, rather than rural, areas. We found statistically significant differences in accuracy in seven out of the eight questions. Regarding the protective effect of fluoride on teeth, accurate perceptions were higher in rural areas, although the difference was not statistically significant. In terms of eating before bedtime, 7.0% of urban children often ate desserts or had sweet drinks before going to bed, a higher percentage than that in rural areas (3.6%) and reflecting a statistically significant difference. In terms of brushing behavior, 81.3% of rural children had not started brushing their teeth before the age of two years and among children who had started brushing their teeth, only 15.0% brushed twice a day. Only 15.2% of parents assist their children aged 3-5 years old with tooth brushing. These statistics are far lower than those of urban children, resulting in statistically significant differences between urban and rural areas. Regarding issues such as using toothpaste when brushing, there were no significant differences, but fluoride toothpaste was only used in 22.9% and 28.2% of children in urban and rural areas, respectively. In rural areas, 45.7% of the children's parents were informed that their children had toothache. From the questionnaires, it was apparent that, of the children who had not seen the dentist in the previous 12 months, 58.4% of these parents did not consider that there might be a problem with their children's teeth. 16.7% of them knew that the children's gums were bad but not serious, while 13.3% thought that there was no need for their children to see dentists since the deciduous teeth will be replaced eventually. Economic reasons for not seeking medical treatment accounted for 0.2%, while reasons due to business accounted for 0.2% (Table 3). In particular, the results show that economic and medical resources are no longer the main factors affecting children's access to medical care in rural areas. Logical regression found that age differences, urban-rural differences, bedtime habits, and parents' educational differences were closely related to the incidence of dental caries in children (Table 4).

Table 2.

The percentage of response on questions of oral health awareness and attitude.

| Urban | Rural | χ 2 | P value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unknown | Yes | No | Unknown | |||

| Awareness | ||||||||

| Gum bleeding is normal when brushing your teeth | 10.6 | 84.0 | 5.5 | 18.9 | 71.4 | 9.7 | 28.217 | 0.000 |

| Bacteria are one of the causes of inflammation of the gums | 89.3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 84.7 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 5.724 | 0.057 |

| Cleaning teeth is not useful for preventing inflammation of the gums | 11.5 | 74.8 | 13.7 | 22.1 | 58.4 | 19.4 | 39.142 | 0.000 |

| Dental caries are caused by bacteria on teeth | 85.5 | 4.8 | 9.7 | 76.1 | 5.6 | 18.2 | 20.069 | 0.000 |

| Sweets can lead to tooth decay | 88.2 | 7.0 | 4.8 | 81.8 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 11.509 | 0.003 |

| Primary teeth do not require treatment | 7.0 | 80.2 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 63.7 | 23.3 | 41.741 | 0.000 |

| Pit and fissure sealant can prevent dental caries of children | 48.6 | 5.1 | 46.3 | 39.0 | 10.4 | 50.6 | 18.650 | 0.000 |

| Fluoride can prevent dental caries of children | 8.9 | 40.8 | 50.3 | 12.4 | 42.9 | 44.6 | 6.075 | 0.048 |

| Attitude | ||||||||

| Oral health is important to life | 98.6 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 98.8 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 1.55 | 0.671 |

| Regular oral examination is necessary | 91.7 | 0.9 | 3.9 | 89.4 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 2.047 | 0.563 |

| Teeth are born good or bad, no correlation with the protection | 7.6 | 88.8 | 3.3 | 12.4 | 83.1 | 3.7 | 9.324 | 0.025 |

| We should rely mainly on ourselves to prevent oral diseases | 96.6 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 92.8 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 9.215 | 0.027 |

| Protecting the first permanent molar is important | 92.7 | 0.8 | 6.4 | 89.6 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 7.746 | 0.052 |

| Mother's bad teeth can affect children | 40.5 | 33.8 | 25.2 | 29.0 | 38.5 | 31.5 | 19.121 | 0.000 |

Table 3.

Oral health behaviors of children surveyed and related factors affecting children's dental examination.

| Urban | Rural | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | χ 2 | ||

| Eating sweets before sleep | ||||||

| Every day | 45 | 7.0 | 21 | 3.6 | 18.577 | 0.000 |

| Once in a while | 350 | 54.5 | 386 | 65.8 | ||

| Never | 247 | 38.5 | 180 | 30.7 | ||

| Brushing or not | ||||||

| Yes | 541 | 84.3 | 401 | 68.3 | 43.607 | 0.000 |

| No | 101 | 15.7 | 186 | 31.7 | ||

| The age of starting tooth brushing | ||||||

| Before 1 year of age | 61 | 11.3 | 24 | 6.0 | 116.594 | 0.000 |

| Before age of 2 years | 196 | 36.2 | 51 | 12.7 | ||

| Before age of 3 years | 214 | 39.6 | 175 | 43.6 | ||

| Before age of 4 years | 70 | 12.9 | 221 | 23.5 | ||

| Brushing (times per day) | ||||||

| Twice daily or more | 171 | 31.6 | 60 | 15.0 | 48.546 | 0.000 |

| Once daily or more | 314 | 58.0 | 251 | 62.6 | ||

| Helping children brush teeth | ||||||

| Not brushing teeth every week | 56 | 10.4 | 90 | 22.4 | ||

| Every day | 176 | 32.5 | 61 | 15.2 | 56.460 | 0.000 |

| Several times per week | 19 | 3.5 | 9 | 2.2 | ||

| Once in a while | 298 | 55.1 | 542 | 57.5 | ||

| No | 48 | 8.9 | 135 | 14.3 | ||

| Brushing teeth with toothpaste | ||||||

| Yes | 520 | 96.1 | 387 | 96.5 | 1.304 | 0.521 |

| No | 13 | 2.4 | 6 | 1.5 | ||

| Unknown | 8 | 1.5 | 8 | 2.0 | ||

| Use of fluoride toothpaste | ||||||

| Yes | 119 | 22.9 | 109 | 28.2 | 40.283 | 0.000 |

| No | 207 | 39.8 | 78 | 20.2 | ||

| Unknown | 194 | 37.3 | 200 | 51.7 | ||

| Discomfort in the past year | ||||||

| Never | 389 | 60.6 | 294 | 50.1 | 13.785 | 0.003 |

| Sometimes | 207 | 32.2 | 241 | 41.1 | ||

| Often | 25 | 3.9 | 27 | 4.6 | ||

| Unknown | 21 | 3.3 | 25 | 4.3 | ||

| Used to check teeth | 222 | 34.6 | 186 | 31.7 | 1.157 | 0.282 |

| Did not check teeth due to | ||||||

| Teeth are not causing problems | 265 | 57.1 | 362 | 58.4 | 0.166 | 0.683 |

| Teeth are not very bad | 72 | 15.5 | 75 | 16.7 | 0.224 | 0.636 |

| No need to check primary teeth | 76 | 16.4 | 60 | 13.3 | 1.673 | 0.196 |

| High cost | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | 0.000 | 0.983 |

| Inconvenient | 6 | 1.3 | 5 | 1.1 | 0.064 | 0.801 |

| Busy work | 18 | 3.9 | 17 | 3.8 | 0.006 | 0.936 |

| Child afraid of dentist | 31 | 6.7 | 31 | 6.9 | 0.016 | 0.901 |

| No dentist nearby | 2 | 0.4 | 10 | 2.2 | 5.657 | 0.017 |

| Fear of infectious diseases | 10 | 2.2 | 8 | 1.8 | 0.169 | 0.681 |

| Distrust dentist | 19 | 4.1 | 14 | 3.1 | 0.635 | 0.425 |

| Kindergarten provides dental examination | 39 | 8.4 | 40 | 8.9 | 0.068 | 0.795 |

| Parents' education | ||||||

| Junior high school and below | 112 | 17.4 | 391 | 66.6 | 395.032 | 0.000 |

| Senior middle school | 119 | 18.5 | 126 | 21.5 | ||

| University and above | 411 | 64 | 70 | 11.9 | ||

Table 4.

Binary logistic regression analysis for the dental caries status.

| B | S.E. | Wals | df | Sig. | Exp (B) | 95% C.I. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.774 | 0.107 | 52.750 | 1 | 0.000 | 2.169 | 1.76-2.673 |

| Urb_rur | -0.834 | 0.205 | 16.503 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.434 | 0.29-0.649 |

| Eating sweets before sleep | -0.282 | 0.144 | 3.846 | 1 | 0.050 | 0.754 | 0.569-1 |

| Parents' education | -0.110 | 0.054 | 4.130 | 1 | 0.042 | 0.896 | 0.806-0.996 |

| Constant | -0.652 | 0.635 | 1.055 | 1 | 0.304 | 0.521 |

4. Discussion

Dental caries not only affect the function and appearance of teeth but may also become a repository for oral microorganisms [9] and may also cause systemic disease. Several mechanisms for this have been proposed, including the spread of the oral infection due to transient bacteremia resulting in bacterial colonization in extraoral sites, systemic infection caused by toxins secreted by oral pathogens, and systemic inflammation caused by soluble antigens from these pathogens [10]. Various diseases, including infective endocarditis [11], brain abscesses [12], and diabetes [13], have been linked to dental caries. These problems are caused by poor oral health; thus, monitoring the development of oral diseases is very important for children's health.

Using multistage stratified sampling, this study conducted an oral examination and parental questionnaires in an effort to understand the current situation of children's oral hygiene with 3-5-year-old children as the target population. A decade ago, a large-scale oral examination targeting 5-year-old children was developed, which revealed that the caries prevalence ratio in urban and rural areas was as high as 64.3% and 83.6%, respectively, while the dmft index was 3.29 and 5.35, respectively [6]. Ten years later, in association with the development of the Chinese economy, accompanied by improvements in living standards, it is apparent that great changes have taken place. The ratios have increased to 81.03% and 93.98% for urban and rural areas, respectively, while the mean dmft indexes have been raised to 4.73 and 7.51, respectively, which are higher than those of many developed countries and regions of developing countries, for instance, Pakistan, India, Europe, and the United States of America [14–19]. Compared with cities such as Shanghai and Guangzhou, it is worrisome that these values are still relatively high [20]. The main concerns are the increasing number of people suffering from caries; the increasing number of caries in children, as well as the early age; and the significant difference between urban and rural areas.

Compared with the survey in 2005 [6], this survey included the additional age group of children aged 3 and 4 years old. The findings showed that up to 75% of rural children suffered from caries at the age of three. It has been reported [21–23] that when caries occur at an early age, it will not only harm the children's oral health but also have a significant influence on their nourishment, mental health, and even quality of life. Early intervention during pregnancy and management of family behavior patterns are conducive to reducing the incidence of caries, particularly decreasing the incidence at preschool age, and thus enhancing their quality of life [24, 25]. Therefore, the prevention of dental caries should be instituted as early as possible; specifically, relevant measures ought to be taken in early pregnancy and after birth.

The position of caries was found to be, in a descending order of frequency, the maxillary anterior teeth, lower mandible deciduous molar, upper mandible deciduous molar, and mandibular anterior teeth. Two caries per child were found to be the most common, accounting for 12.4%. The deciduous molar has many deep fissures predisposing it to the formation of caries and subsequent loss. Monte-Santo et al. [26] observed that an early loss of molars produces a relatively large impact on oral health-related quality of life, which affects both children's physical and mental development. After a one-year follow-up, Honkala et al. [27] believed that pit and fissure closure is an effective means to prevent dental caries, especially for preschool children.

Fluoride toothpaste is an effective way to prevent caries and remove dental plaque, which has been widely recognized and actively promoted by researchers. According to surveys, in rural areas, 31.7% of rural children aged 3 and 5 years old still had not started brushing their teeth, while the number of children who brushed their teeth twice a day had increased by 7.5% to 15.0% compared to a decade ago [6]. About 15.2% of parents assist their children with tooth brushing. However, the usage rate of fluoride toothpaste was only 28.2%. These figures do seem to be better in urban areas. With the exception of the use of fluoride toothpaste, the other factors are higher than in the rural areas, showing statistically significant differences. Healthy habits contributed substantially to the relatively good performance in urban areas observed in the survey. Despite Oliveira et al.'s [28] views on the effect of fluoride in preventing caries in a short period of time, the majority of published studies [29, 30] indicate that a suitable amount of fluoride or fluoride toothpaste is able to prevent caries. Therefore, the popularization of fluoride toothpaste is an effective way to reduce the caries prevalence rate, especially in rural areas.

For the parental questionnaires, it was found that parents' oral health awareness has improved significantly in the past decade, especially in rural areas. For instance, the accuracy of the question “pit and fissure closure can prevent caries” increased from 7.6% to 39%, while the accuracy of “bleeding gums when brushing teeth is a normal phenomenon” increased from 53.3% to 71.4% [6], suggesting that rural residents now have a better understanding of oral health. However, compared with eating habits in urban areas, rural children tended to have more desserts and sweet drinks, which is also one of the reasons accounting for the caries prevalence in rural areas. In terms of medical treatment, the oral health-related questions posed to parents showed only two significant differences, namely, “whether suffered from toothache in the past 12 months” and “whether there is a dentist nearby.” However, only small differences were seen in responses to fees, medical conditions, time of treatment, and medical disinfection, suggesting that rural children are equipped with the basic medical essentials. Moreover, the relatively low outpatient rate is mainly due to parents' lack of oral health awareness. In terms of educational background, there are obvious differences between urban and rural parents, and this is closely related to the understanding of oral health.

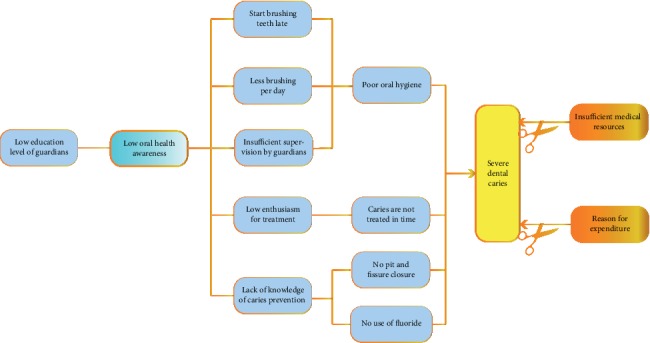

By comparing these results, it is not difficult to find that, compared with urban areas, children in rural areas start brushing their teeth at a later age, brush less often per day, have lower levels of parental involvement, and have insufficient oral disease prevention measures. These differences are the reasons why rural areas are higher in dental caries than urban areas. In particular, we would like to make it clear that, according to the results of our survey, the economic situation of the family and the distribution of medical resources are not the main reasons for the differences. The main reasons for these problems are the relatively low educational background of parents in rural areas and insufficient knowledge of oral health care (Figure 3). The results of this survey are different from people's previous perceptions of the medical situation in China. In the past, people thought that China was a developing country with a large population in rural areas and a lack of medical resources. However, in this situation, the problem is that, compared with their urban counterparts, rural residents do not pay sufficient attention to oral health, rather than being limited by economic conditions or a lack of medical resources.

Figure 3.

Factors affecting the development and treatment of dental caries in a Chinese population.

In conclusion, the deciduous dental caries status of preschool children in North China was found to be still serious. Rural residents do not pay enough attention to oral health, a large number of children with oral problems fail to seek medical treatment in time, and parents do not fully realize the importance of oral health for children's growth. Strengthening oral health education for parents will be one of the most effective ways to improve the oral health of children aged 3 to 5, especially in rural areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants, organisers, and staff who contributed to the Fourth National Oral Health Survey in China. This survey was funded by a grant from Scientific Research Fund of National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China (201502002) and conducted by the Department of Preventive Dentistry, Hospital of Stomatology, China Medical University, China.

Data Availability

The calculated data by statistical software (spss 19.0) used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The original data includes the name, date of birth, ID card code, and other illnesses of respondents, etc., in order to respect the privacy of the respondent. Data are available from [Zhenfu Lu, zflu2006@163.com] for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this article declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Professor Zhenfu Lu has acquired funding for the project and played a role in the design of the study. Dr. Kaiqiang Zhang was involved in drafting and revising the manuscript. Dr. Jian Li has participated in data collection and data analysis of the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Sun X., Bernabé E., Liu X., Gallagher J. E., Zheng S. Early life factors and dental caries in 5-year-old children in China. Journal of Dentistry. 2017;64:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong D., Perez-Spiess S., Julliard K. Attitudes of Chinese parents toward the oral health of their children with caries: a qualitative study. Pediatric Dentistry. 2005;27(6):505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J., Zhang S. S., Zheng S. G., Xu T., Si Y. Oral Health Status and Oral Health Care Model in China. The Chinese Journal of Dental Research. 2016;19(4):207–215. doi: 10.3290/j.cjdr.a37145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granville-Garcia A. F., Gomes M. C., Perazzo M. F., Martins C. C., Abreu M. H. N. G., Paiva S. M. Impact of Caries Severity/Activity and Psychological Aspects of Caregivers on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life among 5-year-Old Children. Caries Research. 2018;52(6):570–579. doi: 10.1159/000488210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeraatkar M., Ajami S., Nadjmi N., Golkari A. Impact of oral clefts on the oral health-related quality of life of preschool children and their parents. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice. 2018;21(9):1158–1163. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_426_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qi X. Report of the Third National Oral Health Survey. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rejali M., Mohammadbeigi A., Mokhtari M., Zahraei S. M., Eshrati B. Timing and delay in children vaccination; evaluation of expanded program of immunization in outskirt of Iranian cities. Journal of Research in Health Science. 2015;15(1):54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (WHO) Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. 5th. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li X., Kolltveit K. M., Tronstad L., Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13(4):547–558. doi: 10.1128/cmr.13.4.547-558.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han Y. W., Wang X. Mobile microbiome: oral bacteria in extra-oral infections and inflammation. Journal of Dental Research. 2013;92(6):485–491. doi: 10.1177/0022034513487559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lockhart P. B., Brennan M. T., Sasser H. C., Fox P. C., Paster B. J., Bahrani-Mougeot F. K. Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation. 2008;117(24):3118–3125. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.758524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.da Silva R. M., Caugant D. A., Josefsen R., Tronstad L., Olsen I. Characterization ofStreptococcus constellatusStrains Recovered From a Brain Abscess and Periodontal Pockets in an Immunocompromised Patient. Journal of Periodontology. 2004;75(12):1720–1723. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.12.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohlrich E. J., Cullinan M. P., Leichter J. W. Diabetes, periodontitis, and the subgingival microbiota. Journal of Oral Microbiology. 2010;2(1) doi: 10.3402/jom.v2i0.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer A.-C. A., Skeie M. S., Skaare A. B., Espelid I., Östberg A.-L. Caries increment in primary teeth from 3 to 6 years of age: a longitudinal study in Swedish children. European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry. 2014;15(3):167–173. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0079-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabhu P., Rajajee K. T., Sudheer K. A., Jesudass G. Assessment of caries prevalence among children below 5 years old. Journal of International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 2014;4(1):p. 40. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.129449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prasai Dixit L., Shakya A., Shrestha M., Shrestha A. Dental caries prevalence, oral health knowledge and practice among indigenous Chepang school children of Nepal. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13(1) doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-13-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azizi Z. The Prevalence of Dental Caries in Primary Dentition in 4- to 5-Year-Old Preschool Children in Northern Palestine. International Journal of Dentistry. 2014;2014:5. doi: 10.1155/2014/839419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jain M., Namdev R., Bodh M., Dutta S., Singhal P., Kumar A. Social and Behavioral Determinants for Early Childhood Caries among Preschool Children in India. Journal of Dental Research, Dental Clinics, Dental Prospects. 2015;9(2):115–120. doi: 10.15171/joddd.2014.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van den Branden S., Van den Broucke S., Leroy R., Declerck D., Bogaerts K., Hoppenbrouwers K. Effect evaluation of an oral health promotion intervention in preschool children. European Journal of Public Health. 2014;24(6):893–898. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanemoto T., Imai H., Sakurai A., et al. Influence of Lifestyle Factors on Risk of Dental Caries among Children Living in Urban China. The Bulletin of Tokyo Dental College. 2016;57(3):143–157. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.2016-0400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naidu R., Nunn J., Donnelly-Swift E. Oral health-related quality of life and early childhood caries among preschool children in Trinidad. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0324-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mantonanaki M., Hatzichristos T., Koletsi-Kounari H., Papaioannou W. Socio-demographic and area-related factors associated with the prevalence of caries among preschool children in Greece. Community Dental Health. 2017;34(2):112–117. doi: 10.1922/CDH_4034Mantonanaki06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vollú A. L., da Costa M. d. E. P. R., Maia L. C., Fonseca-Gonçalves A. Evaluation of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life to Assess Dental Treatment in Preschool Children with Early Childhood Caries: A Preliminary Study. The Journal of Clinical Pediatric Dentistry. 2018;42(1):37–44. doi: 10.17796/1053-4628-42.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wigen T. I., Espelid I., Skaare A. B., Wang N. J. Family characteristics and caries experience in preschool children. A longitudinal study from pregnancy to 5 years of age. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2011;39(4):311–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wigen T. I., Wang N. J. Maternal health and lifestyle, and caries experience in preschool children. A longitudinal study from pregnancy to age 5 yr. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 2011;119(6):463–468. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00862.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monte-Santo A. S., Viana S. V. C., Moreira K. M. S., Imparato J. C. P., Mendes F. M., Bonini G. A. V. C. Prevalence of early loss of primary molar and its impact in schoolchildren's quality of life. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry. 2018;28(6):595–601. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Honkala S., ElSalhy M., Shyama M., al-Mutawa S. A., Boodai H., Honkala E. Sealant versus Fluoride in Primary Molars of Kindergarten Children Regularly Receiving Fluoride Varnish: One-Year Randomized Clinical Trial Follow-Up. Caries Research. 2015;49(4):458–466. doi: 10.1159/000431038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira B. H., Salazar M., Carvalho D. M., Falcão A., Campos K., Nadanovsky P. Biannual fluoride varnish applications and caries incidence in preschoolers: a 24-month follow-up randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Caries Research. 2014;48(3):228–236. doi: 10.1159/000356863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blinkhorn A. S., Byun R., Mehta P., Kay M. A 4-year assessment of a new water-fluoridation scheme in New South Wales, Australia. International Dental Journal. 2015;65(3):156–163. doi: 10.1111/idj.12166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baygin O., Tuzuner T., Kusgoz A., Senel A. C., Tanriver M., Arslan I. Antibacterial effects of fluoride varnish compared with chlorhexidine plus fluoride in disabled children. Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry. 2014;12(4):373–382. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a32129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The calculated data by statistical software (spss 19.0) used to support the findings of this study are included within the article. The original data includes the name, date of birth, ID card code, and other illnesses of respondents, etc., in order to respect the privacy of the respondent. Data are available from [Zhenfu Lu, zflu2006@163.com] for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.