Abstract

Interpersonal violence is present at all levels of influence in the social ecology and can have comprehensive and devastating effects on child and adolescent development through multiple simultaneous channels of exposure. Children’s experiences with violence have been linked with a range of behavioral and mental health difficulties including posttraumatic stress disorder and aggressive behavior. In this article, we offer a conceptual framework delineating the ways in which children and adolescents might encounter violence, and a theoretical integration describing how violence might impact mental and behavioral health outcomes through short- and long-term processes. We propose that coping reactions are fundamental to the enduring effects of violence exposure on their psychosocial development and functioning. Finally, we discuss the manner in which coping efforts can support resilience among children exposed to violence and suggest new directions for research and preventive intervention aimed at optimizing outcomes for children at risk of exposure.

Keywords: violence exposure, community violence, domestic violence

Violence in society is ubiquitous and may be found in every domain of social experience—in homes, neighborhoods, broader communities, schools, the political arena, and all forms of mass media. Following ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 2005), interpersonal violence thus can have quite comprehensive and devastating effects on development through multiple simultaneous channels of exposure (Boxer et al., 2012; Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2007; Mrug, Loosier, & Windle, 2010). Exposure to violence has been linked consistently to a range of psychological problems in children and adolescents1 including traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, substance use, aggressive and antisocial behavior problems, and academic difficulties (Lynch, 2003).

Although prevalence rates of exposure to very serious acts of violence (e.g., murder, severe physical assaults) might be expected to be relatively low, estimates of children’s exposure to a range of events underscore the fairly broad scope of the problem. For example, with respect to violence in the home, nationally representative data suggest that about 11–14% of children report experiencing some form of parental maltreatment whereas about 4–5% report witnessing interparental violence or child physical abuse (Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2010). Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, and Hamby (2010) reported that about 25–30% of children have witnessed some form of violence in their neighborhoods or communities and that 53–59% of children have experienced some degree of violence as witnesses or victims in their sibling relationships or peer groups. Results from the Center for Disease Control’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance indicate consistently over time that about 12–16% of high school students report involvement in at least one physical fight at school per year). Finally, according to nationally representative data collection, about 86% of youth watch violent television shows, 65% play violent video games, 57% listen to violent music, 43% view simulated violence on the Internet, and 15% view real violence on the Internet (Ybarra et al., 2008). These estimates support the view that violence can be omnipresent in the lives of children and adolescents. This idea is underscored by data showing that nearly 22% of children are “polyvictims” via exposure to four or more discrete forms of violence as either witnesses and/or victims (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2010).

Despite a wealth of literature on the impact of violence exposure on children, there is still a notable absence of systematic inquiry and accumulated knowledge to address three critical questions: First, how do children actually encounter violence? That is, what are the different configurations of exposure to violence—for example, across multiple contexts or at varying degrees of chronicity—that might lead to adverse outcomes? Second, to what extent do causal mechanisms that help explain effects of one form of exposure also explain effects of another, or possibly multiple, co-occurring forms of exposure? The third question focuses on coping and resilience, concepts at the center of the discussion for this special issue: How do children cope with violence exposure in ways that are protective from the lasting emotional or psychological harms otherwise thought or shown to be linked to exposure?

A primary goal of this article is to review the empirical literature on the impact of violence exposure for children and adolescents. In considering the many ways youth might experience, cope with, and adapt to violence over time, we offer a conceptual framework delineating different contexts, contents, and channels of violence exposure. We then offer a theoretical integration based on the extant research and related theorizing to describe how violence might impact different, discrete mental and behavioral health outcomes through both short-term and long-term processes. We propose that short-term coping reactions—immediate situational responses to violence—are fundamental to the enduring effects of violence exposure on psychosocial development and functioning. Finally, we suggest new directions for research and preventive intervention aimed at identifying and shaping self-protective factors that could be trained or optimized through targeted programs for children at risk of exposure.

Documenting the Impact of Violence Exposure on Children and Adolescents

Youth can be exposed to violence as victims or witnesses, or both. Exposure can occur in a number of different settings, including homes, schools, and neighborhoods. Youth can be exposed to violence on a single occasion, on several occasions episodically (e.g., shootings in the neighborhood, physical fights between parents), or on multiple occasions (e.g., repeated physical fights in school, chronic exposure to domestic violence, and/or ongoing corporal punishment at home). Exposures to violence also differ according to nature of the violence in question. Some youth might encounter only mild or nonserious forms of violence (e.g., pushing and shoving at school); others may encounter more serious violent events, such as homicides or aggravated assaults. The empirical literature is clear that exposure to violence is damaging to children’s emotional and behavioral health, with documented associations between exposure and depression, anxiety, aggression, substance use, posttraumatic stress, somatic problems, and academic difficulties (for reviews, see, e.g., Fowler, Tompsett, Bracizewski, Jacques-Tiura, & Baltes, 2009; Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003; Mazza & Overstreet, 2000). The effects of violence might be relatively immediate, impacting children’s functioning over the short term, or longer lasting, potentially into adulthood (Margolin & Gordis, 2000). Whether different, discrete forms or configurations of exposure are linked to different patterns or profiles of adverse outcomes, however, is still an open empirical question.

Increasingly clear is the observation that many children might be exposed simultaneously to violence in multiple forms and contexts, rendering the social ecology for some children as one that is steeped completely in violence, with associated greater risks for negative outcomes (Boxer et al., 2012; Finkelhor et al., 2010; Herrenkohl, Sousa, Tajima, Herrenkohl, & Moylan, 2008). In some regions of the world (e.g., the Middle East, parts of Africa), this even includes the broader political–cultural environment in which deeply seated ethnic and sociopolitical conflicts have insidious effects on children’s everyday lives (Dubow, Huesmann, & Boxer, 2009). For example, Boxer et al. (2012) found that political violence led over time to increased community, school, and family violence, and in turn to increases in children’s aggression toward their peers. Importantly, despite the studies documenting that exposure to violence is a risk factor for a number of different adverse outcomes, and the multifaceted nature of children’s exposure experiences, there has been little effort in the scholarly literature directed toward integrating these variations into a conceptual framework for research, theory, and intervention.

Evidence suggests that exposure to violence adversely impacts the mental health of children and adolescents, but there are serious concerns about the measurement and analysis strategies used by researchers to understand individuals’ experiences with violence in their social environments (Brandt, Ward, Dawes, & Flisher, 2005; Guterman, Cameron, & Staller, 2000; Netland, 2001; Trickett, Durán, & Horn, 2003). For example, although consensus has been reached on an operational definition of “violence” (i.e., acts that have the potential to cause physical pain or injury to another), there is no such consensus about the meaning of “exposure.” Exposure to violence can include witnessing violence, being directly victimized by violence, and possessing knowledge of violence. Indeed, across studies, there is great variation in definitions of exposure as well as in how violence is operationalized and scale construction methodology (Brandt et al., 2005; Guterman et al., 2000; Trickett et al., 2003). The research literature on youths’ exposure to violence also is quite disparate with respect to assessing the contexts in which violence occurs. Despite long-standing developmental theory underscoring the importance of social influences at multiple ecological levels or systems (e.g., Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Sameroff, 1991, 2010), studies of youth violence exposure typically focus on single ecosystems (e.g., family). Although there are extensive literatures on the effects on youths’ mental health of family violence (e.g., Holden, Geffner, & Jouriles, 1998; Kitzmann et al., 2003), community violence (e.g., Buka, Stichik, Birdthistle, & Earls, 2001; Lynch, 2003), and school-based violence (e.g., Flannery, Wester, & Singer, 2004; Kumpulainen et al., 1998), relatively little research by comparison has cut across these domains to investigate the cumulative or interactive effects of violence at multiple ecological levels.

Another key issue in the study of how violence impacts children is the nature of the violence itself—the sheer magnitude or topography of the act. Studies have produced evidence suggesting that a wide range of violent or potentially violent acts can be harmful, running a gamut from “low level” acts of harassment, mild physical aggression, and relational victimization (Boxer, Edwards-Leeper, Goldstein, Musher-Eizenman, & Dubow, 2003; Goldstein, Young, & Boyd, 2007) to more extreme events such as physical or sexual abuse, ethnic–political violence or terrorism, or spousal abuse (Boxer et al., in press; Boxer & Terranova, 2008; Hughes, Parkinson, & Vargo, 1989). Although theory and research do exist to suggest potential differences in the impact of events as the function of their perceived or lived severity in tandem with their chronicity, empirical studies have been quite limited in how these features have been conceptualized, addressed methodologically, and measured. A related point here is the duration of children’s exposure to violent conditions or the timing of their exposure to discrete violent events. Developmental theory suggests that the effects of violence might differ in relation to a child’s age at the time of exposure, with earlier, more severe, and more chronic events producing more lasting impact (i.e., early childhood exposures). Again, though this is a critical issue—especially from the standpoint of intervention—empirical studies generally have been limited with respect to inquiry into the question of how the duration or developmental timing of violence exposure relates to children’s outcomes. A key exception, however, has been research in child maltreatment suggesting that earlier maltreatment is associated with poorer outcomes (e.g., Thompson & Tabone, 2010).

At present, the clearest statement about how violence negatively impacts children and adolescents might simply be: It does. Such a pithy statement of effects does not do justice to the vast array of empirical studies that have been conducted, but it does acknowledge a key point advanced by Kuther and Wallace (2003) that still appears to hold weight: The data showing evidence of adverse impacts from violence have out-paced the ability of current theory to explain those impacts. However, as delineated above, part of the problem lies with the fact that the data themselves have come with a number of limitations and qualifications accruing from measurement methods and the analytic aims and techniques following from those methods.

In our own empirical work, we recently have adopted a four-dimensional framework for conceptualizing inquiry into the effects of violence on children. The purpose of this framework is to address directly the limitations of previous studies with respect to the measurement of exposure. Broadening the operational conception of exposure is also critical for moving forward our understanding of the contextualized nature of children’s reactions to violence.

A Four-Dimensional Framework for Understanding Children’s Exposure to Violence

As suggested, violence can come in many forms with the potential for a variety of operational definitions. We focus on physical forms of violence and rely on the operational definition put forth by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (NCIPC) of the CDC—”the intentional use of physical force with the potential for causing death, disability, injury, or harm” (Saltzman, Fanslow, McMahon, & Shelley, 2002). Of course, “harm” is subject to many interpretations including psychological harm (Dahlberg & Krug, 2002) and thus we incorporate into our conception mild or “low level” acts of physical aggression (Boxer et al., 2003). The four-dimensional framework (see Figure 1) proposes that any act of violence may be summarized along two categorical and two continuous dimensions that are relevant to children’s behavioral and mental health outcomes: context, content, channel, and chronicity. The first dimension is context—that is, the social setting in which the act of violence occurs. Context may be defined by physical space, as in the confines of a home or on a particular sidewalk block in a neighborhood; or it may be defined by social or psychological space, as in a group of family members or peers. There can be some overlap with respect to social and physical spaces—for example, a violent act might occur among a group of peers congregating within one youth’s home, or a violent family altercation might erupt in a public park. Because these domains mirror the model of nested social ecosystems proposed by Bronfenbrenner (1979), when the social and physical contexts are not congruous the impact of the violent event probably accrues as a function of the more proximal social context rather than the actual physical setting (e.g., a violent family altercation is most likely experienced as an incident of family violence regardless of where it occurs). Of course, this is an empirical issue that to our knowledge has not heretofore been subject to scrutiny.

Figure 1.

A four-dimensional framework for understanding violence exposure.

The second dimension is content—that is the nature of the act itself. There seems to be an endless array of different violent behaviors (e.g., fist fighting, use of weapons, pushing, and shoving), but the intent of this dimension is to capture the severity of the violent act across a variety of specific acts. Quite dissimilar acts ultimately can lead to the same destructive outcome (e.g., both stabbing and shooting can result in serious bodily injury or death). At the least severe end of this continuum, a violent act might involve, per the NCIPC’s definition, only the potential or threat of physical impact (e.g., a spoken threat, the presence of a weapon during a verbal altercation). At the most severe end, a violent act might involve catastrophic impact (e.g., murder). Functionally, the intent of this dimension is to capture quantitatively an index of the potential impact on the child of violence exposure.

The third dimension is channel— that is the mode of exposure or the way in which the youth experiences the violent act. The few studies systematically incorporating aspects of this dimension (e.g., witnessing violence versus being victimized by violence) have underscored the great importance to theory as well as practice of assessing the channel of exposure. For example, witnessed violence appears to socialize an aggression-supporting cognitive style, whereas victimization by violence seems to interfere with emotion regulation (Boxer et al., 2008; Schwartz & Proctor, 2000). Previous work, however, has not elaborated and assessed enough the multiple ways in which youth can experience violence. For example, how are youth impacted by learning of violent incidents in their neighborhoods via word of mouth? What is the relative impact of hearing, but not seeing, a violent event occurring nearby (e.g., the screams of an individual being beaten and/or robbed) versus viewing and hearing the event directly? These are critical questions that have not been addressed systematically. Our conception also includes specific attention to media-mediated exposure to violent events (e.g., through local television news reports), a facet of the exposure channel often left out of the research in this area but one that clearly can be impactful (Anderson et al., 2003; Schuster et al., 2001).

Our fourth and final dimension is chronicity—that is, the frequency of exposure to the particular type of violent event. This dimension is essential to addressing the larger question of how exposure to violence exerts effects. Research has shown that recent exposure affects adjustment differently than does accumulated exposure (Jaycox et al., 2002; Lynch, 2003). As we discuss below, theory and empirical evidence support a dual-process model in which short-term or temporally proximal exposure impacts behavioral and mental health through intense emotional arousal and coping reactions to that arousal, whereas long-term or temporally distal or chronic exposure affects mental health by modifying more enduring cognitive and emotion-regulatory structures (Boxer et al., 2008; Bushman & Huesmann, 2006). A critical as-yet unaddressed question is whether, for example, single exposures to high-impact and proximal events (e.g., witnessing the murder of a parent; Eth & Pynoos, 1994) are more damaging to mental health or overall psychosocial functioning than are repeated exposures to less severe but potentially more insidious events (e.g., growing up in a perpetually violent and crime-saturated neighborhood; Guerra, Huesmann, & Spindler, 2003). The extant literature base is hampered greatly by an almost universal reliance on only two time frames of assessment—exposure within the year prior to assessment, or exposure at any point during the lifetime (Brandt et al., 2005).

Our four-dimensional model is intended to form the basis of a more contextually sensitive consideration of how experiences with violence affect children’s outcomes, and serve as a descriptive foundation for advancing hypotheses concerning the processes that might mediate the link between violence exposure and outcomes. As noted earlier, we view coping reactions as the primary short-term process accounting for the impact of violence on subsequent adjustment; yet, coping strategies and styles can be highly contextualized (see Tolan & Grant, 2009). We expect that the reactions and/or selected coping tactics of children experiencing violence, either episodically or more chronically, also will be sensitive to the particular contextual configuration of their exposure (see Reid-Quiñones et al., 2011). We thus now turn to a discussion of how coping reactions might function to promote better adjustment or augment risk of maladjustment under conditions of exposure to violence.

How Exposure to Violent Events Impacts Short-Term Outcomes

As noted briefly above, our conception of how violence exposure impacts children’s short-term outcomes rests on coping processes. Broadly speaking, coping efforts are meaningful behavioral, cognitive, and/or emotional steps taken in order to reduce or eliminate stressors as well as the psychological distress associated with the stressors (Dubow & Rubinlicht, 2011; Folkman, 1984). When children experience a discrete traumatic or highly stressful event, or live under conditions of persistent stress, selected coping responses or habitual coping styles can make the difference between successful or unsuccessful adaptation. Some forms of coping (e.g., constructive problem solving, effortful emotion regulation) result in improved adjustment and adaptation whereas others (e.g., avoidance, withdrawal) lead to worse adjustment and maladaptation (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Thomasen, & Wadsworth, 2001). Within a generalized resilience framework, positive coping skills are essential moderators that create protective or stress-buffering effects in the context of risk (Dubow, Roecker, & D’Imperio, 1997).

Coping strategies selected in response to stressful events are contextualized in line with youths’ construction of the controllability of the event and the actual content and context of the event itself along with sociocultural factors, learning histories, and personal resources (Compas et al., 2001; Tolan & Grant, 2009). A number of studies support the idea that how a youth responds to a particular stressor is linked to stable background factors as well as stress mobilization processes in which stressors elicit corresponding coping reactions, potentially in highly specific ways (Bjorck & Cohen, 1993; Dubow, Pargament, Boxer, & Tarakeshwar, 2000). Despite this potential for specificity, researchers have identified several more or less replicable higher-order categories of coping response, divided conceptually across the two broad categories of approach or engagement coping and avoidance or disengagement coping (Causey & Dubow, 1992; Compas et al., 2001; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Approach or engagement coping efforts typically are linked to better behavioral and mental health outcomes for children and adolescents, and thus considered “positive coping.” Positive coping has been subdivided further into two fundamental types—problem focused, primary control, or active coping, which generally includes attempts to modify salient aspects of a stressful event (e.g., problem solving); and emotion focused, secondary control, or accommodative coping, which generally includes attempts to change the nature of cognitive (e.g., optimistic thinking) or emotional (e.g., arousal reduction) reactions to a stressful event (Causey & Dubow, 1992; Connor-Smith & Compas, 2004; Roth & Cohen, 1986; Weisz, McCabe, & Denning, 1994).

Avoidance or disengagement coping is considered “negative coping,” given that these sorts of coping efforts typically are linked to emotional symptoms or problem behaviors such as high anxiety or maladaptive behavioral conduct (Causey & Dubow, 1992; Dempsey, 2002). Negative coping strategies involve distancing oneself psychologically or physically from a stressful event, acting out or “venting” anxious or angry arousal (i.e., externalized coping), or retreating inward emotionally through worry, sadness, or self-pity (i.e., internalized coping). Studies of both positive and negative coping have observed a fair degree of variability in the forms of coping youth select in response to a variety of stressors. However, probably due to its uncontrollability, researchers typically have observed that youth respond with avoidant or disengaged or similarly negative forms of coping in response to violence, although not exclusively so (Boxer et al., 2008; Dempsey, 2002; Kliewer et al., 2006; Reid-Quiñones et al., 2011; Scarpa & Haden, 2006; Tolan, Gorman-Smith, Henry, Chung, & Hunt, 2002).

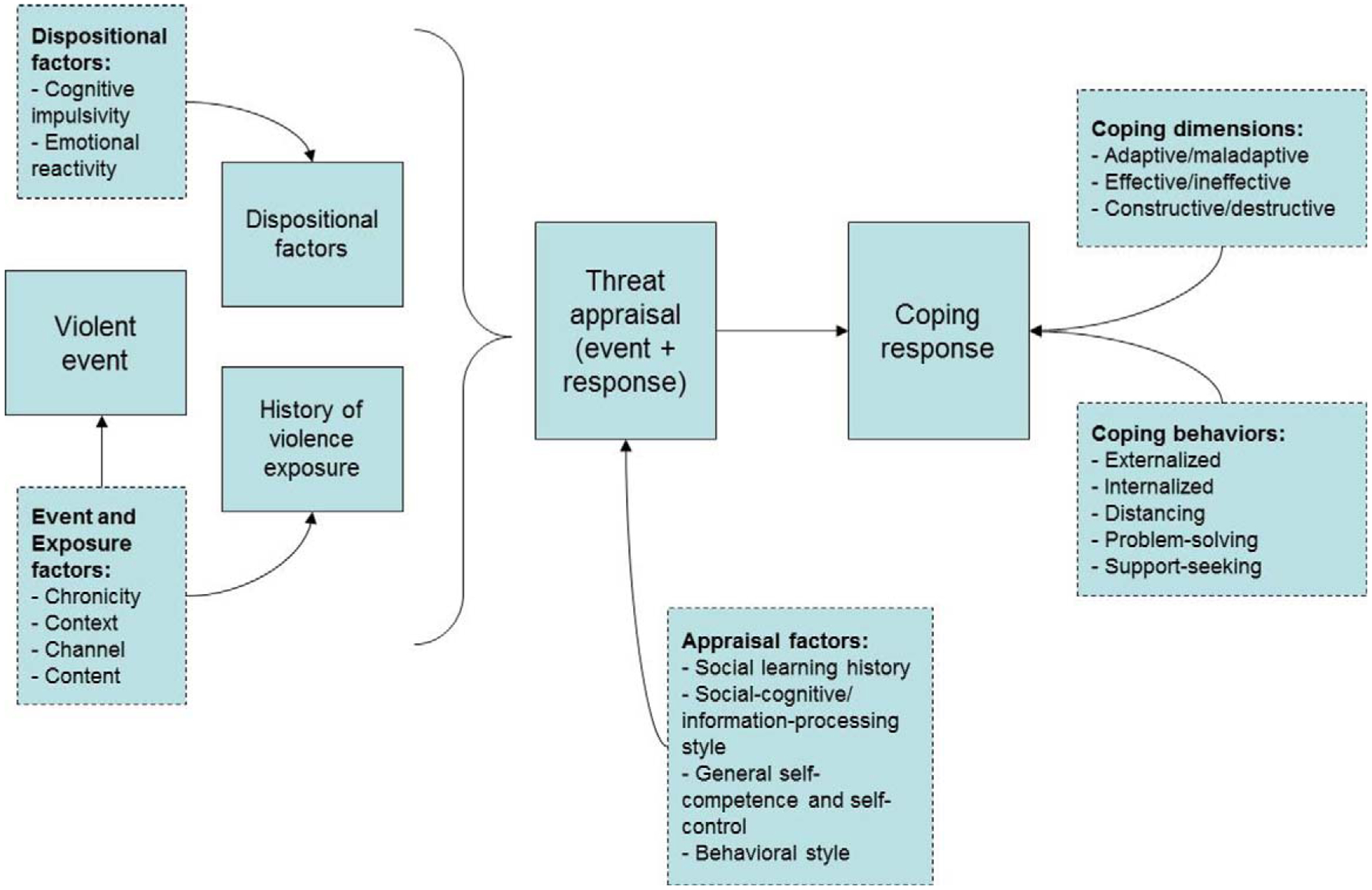

The bottom line with respect to beginning to understand how violence impacts children’s adjustment is to recognize that violence—whether it is encountered as a witness or a victim, and regardless of the context—can represent threat, and to a large extent children exposed to violence must appraise that threat to determine how to respond. A number of factors likely play into how children appraise the threat of violence—from the standpoint of how they construe the nature of the threat and how they construct their possible responses to the threat. Figure 2 displays our model of how these appraisals might inform the selection of different categories of coping response.

Figure 2.

A model of how background factors influence coping responses to violent events.

Before discussing the details of the framework it is worth emphasizing here that we approach children’s social behavioral development from the standpoint of a generalized developmental-ecological view—that is, the basic notion that children’s behavior in terms of situational reactions as well as habitual styles of response is fundamentally the product of personal, dispositional factors such as temperament, cognitive ability, and activity levels, and contextual factors such as socialization by parents, peers, and the media (see, e.g., Boxer, Terranova, Savoy, & Goldstein, 2008; Guerra & Huesmann, 2004). It is essential here also to recognize that children’s development is reciprocal—not only are they influenced by their social environments in myriad ways, they also influence those environments through their responses to them, and their presence in them (Bronfenbrenner, 2005; Sameroff, 2010). Thus, our conceptual model begins with the proposition that children’s appraisals of violent events are influenced by a number of factors.

In the general sense, how children perceive violence should relate in part to their own dispositions and in particular their unique degrees of emotion reactivity and/or cognitive impulsivity (i.e., atendency to perform academic or intellectual tasks too quickly and without planning). Children who maintain high stable levels of negative affectivity dispositionally (e.g., anxiety, fear, and anger) or who are highly emotionally labile or react quickly to aversive situations with intense negative arousal should be more likely to appraise violent events as highly threatening or personally challenging. Children who tend to react impulsively to situations, opting for the first response options that come to mind, or who tend not to engage in reflective problem solving about that nature of events, might fail to account for alternative explanations for violent events that could lead them to make safer or more constructive appraisals. At the same time, children’s appraisals of violent events—their likely stability, specificity, and causal origins as well as the extent to which the violence can be meaningfully addressed by them or others near to them—have got to be linked to children’s own personal histories of violence and how they adapted or responded to those experiences, over and above any personal dispositions or other contextual learning experiences they might have had. This sort of history, if it has proven beneficial with respect to producing more or less accurate appraisals of violent events, might create what has been referred to in the literature (though infrequently) as “street smarts” with respect to dealing with violence in the community (Howard, 1996). Of course, despite any volitional construals of or reactions to violent events, some degree of children’s responses will be involuntary through classically conditional emotional reactions and natural central nervous system reactions to stress (Dubow & Rubinlicht, 2011).

Within the broader developmental–ecological view, we view children’s responses to social–environmental stimuli as emanating through social–cognitive information-processing (SCIP) mechanisms. In this framework, a child’s cognitions related to social situations and social behavior are thought to drive immediate behavioral responses to events and account for the association over time between individual and environmental risk factors and actual social behavior (Crick & Dodge, 1994; Guerra & Huesmann, 2004; Huesmann, 1998). Thus, SCIP factors represent an internal mediating system linking dispositional and contextual inputs to behavioral outputs. According to SCIP theorizing, over time and across situations the process by which a youth initially attends to and interprets environmental cues, searches for and evaluates potential behavioral responses, and then evaluates the consequences of the chosen responses determines whether a behavior enacted situationally will become an enduring style of behavioral response. Although much of the work on SCIP models for understanding behavior has been applied to understanding the development of aggression, it is a contemporary iteration of long-standing social learning theory (Bandura, 1986), which has broad relevance for all behavioral outcomes. As we assert here, SCIP has clear application to understanding threat appraisals and coping response selection, given that both are essentially cognitive–behavioral processes in the context of social interaction.

The basic SCIP framework postulates that behavioral response patterns are represented mentally as “scripts”—cognitive structures “laying out the sequence of events that one believes are likely to happen and the behaviors that one believes are possible or appropriate for a particular situation” (Huesmann, 1998, p. 80). These scripts are acquired over time as the function of observational and direct learning experiences, which are themselves in part the function of dispositional behavioral tendencies that increase or decrease the potential for a child to be exposed to different learning experiences. Though scripts are central to SCIP in social behavior, given that they subsume the full process of response selection through response evaluation, SCIP is comprised of two general cognitive functions—”on line” skills that drive the situational selection of behavioral responses and crystallized structures that support habitual response patterns. Theorists have offered detailed stepwise schematics for explaining the extended process through which situational cues (i.e., internal cues including arousal and external cues including social events and contextual characteristics) lead to behavior. These processing steps can be classed within three categories (Boxer, Goldstein, Musher-Eizenman, Dubow, & Heretick, 2005): (1) interpreting the causes of situational events; (2) generating and selecting appropriate behaviors to enact; and (3) interpreting and evaluating the consequences of chosen behaviors. Although these steps initially have been offered to describe behavior responses generally, and with specific regard to aggressive responding, they are just as apt in terms of understanding how children might select coping responses.

How an individual attributes the cause of some event is a fundamental first step in determining the individual’s response to that event. As shown in Figure 2, prior to a child’s immediate social–cognitive processing or appraisal of the potential threat posed by a violent event, the child already has a template for event interpretation comprised of his or her temperamentally based emotional reactions, historical experiences, and the discrete nature of the event itself. All of these pieces of data serve to inform a child’s perception of the nature of a potentially threatening event. For example, Dodge and colleagues have shown fairly conclusively that children with histories of physical abuse are hypervigilant to signs of hostile intent in ambiguous situations (e.g., Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1990), while Pollak and colleagues have demonstrated that maltreatment experiences meaningfully impact children’s ability to attend to and process emotional stimuli, with clear implications for social interaction (e.g., Pollak, 2008). These two strands of research suggest that maltreated children are at greater risk of aggression through hostile attributional biases about others’ intentions (Dodge et al., 1990), and anxiety through overattention to threatening cues in their environments (Pollak, 2008). Thus, it is important to bear in mind that along with research suggesting that children’s coping reactions intentionally are tailored to match the stressors to which they must respond (Dubow et al., 2000), how a child copes is also going to be associated with his or her personal characteristics and experiences.

We already have discussed the variety of potential coping reactions as they have been conceptualized and categorized by other scholars (e.g., Compas et al., 2001); however, we must also emphasize that there is a clear but not by any means determined relation between the intentional aims of a coping reaction and the actual consequences of that reaction. For example, a child might opt for a problem-solving response to a problem that is not inherently solvable by the child, such as peer victimization (e.g., Terranova, Boxer, & Morris, 2010) or other forms of violence. Thus, the consequences of the child’s coping response are necessary to consider when evaluating the coping response overall. As Tolan and Grant (2009) have noted, coping occurs in a broader social–cultural context in which the outcomes of coping reaction may be conceptualized with respect to the effectiveness of the coping effort and ultimately its role in promoting adaptation or maladaptation or a pattern of constructive or destructive behavior. For instance, distancing or avoidance coping (e.g., trying to put an upsetting event out of mind or ignore the negative arousal associated with it) might be problematic or negative in the context of an episodic event that is amenable to problem-solving or approach strategies such as the loss of a loved one. However, in the presence of a chronic stressor that cannot be alleviated through approach strategies—such as community violence—distancing coping might promote positive adaptation (Boxer, Sloan-Power, Mercado, & Schappell, 2011). What this suggests is that although broad classes of coping response have been identified as generally “positive” or “negative” by virtue of their impact on behavioral/mental health, higher level contextual factors must be taken into account in order to make a broader and clearer inference about whether a coping response is useful, effective, or adaptive.

How Chronic Exposure to Violence Impacts Long-Term Outcomes

Just as individual acts of coping occur in a broader social context, children’s short-term reactions to events occur in a much longer temporal sequence of behavioral development. With some exceptions, the literature on children’s coping includes very little data on the long-term outcomes of coping styles or even longitudinal trends in children’s patterns of reaction to stress (Dubow & Rubinlicht, 2011). We believe this partly results from a heretofore preference in the research for documenting and understanding the correlates of the many varieties of coping, but also partly from a relatively limited operationalization and measurement of coping. For example, one broad definition that has been offered of coping is that it represents “ongoing cognitive and behavioral processes to manage external or internal demands exceeding the resources of the individual” (Dubow & Rubinlicht, 2011, p. 109). Yet, as Dubow and Rubnlicht (2011) note, external and internal demands often are considered “stressors,” and thus a more precise operationalization that typically is utilized in the research is coping as “the specific set of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional responses enacted following the experience of a stressor” (pp. 109–110). This is of course a useful definition, but it is important to recognize that when coping reactions become habitual coping styles, they might generalize to habitual behavior writ large. Given what we know about violence as a stressor—that it is largely uncontrollable and can be chronic as well as episodic, causing a variety of emotional and cognitive reactions—there are several ways in which situational coping reactions can reify over time into habitual coping styles with great relevance to everyday behavior. We theorize that there are two principal bridges between situational responses and habitual styles—cognitive processing and structural functions hinging on social goal orientation and sociomoral evaluative beliefs about behavior, and emotion regulatory functions targeting the routine management of arousal. Figure 3 illustrates our ideas.

Figure 3.

A model describing how short-term coping reactions might lead to long-term habitual behavior and adaptation.

As suggested earlier, our ideas rest on the assumption that an individual’s behavior at any moment has been determined by interactions over time among individual biopsychological characteristics (e.g., emotional reactivity), historical and ongoing contextual socializing influences (e.g., parenting), and current situational instigators (e.g., violence; Dodge & Pettit, 2003). The connections among individual and contextual influences and subsequent behaviors are theoretically accounted for by cognitive processing and emotion regulatory styles that emerge early in development and begin reliably to predict behavior by about middle childhood (Davis-Kean et al., 2008). That is, as a child grows and develops, inborn predispositions interface with a variety of environmental stimuli to produce internal cognitive and emotion regulatory for handling everyday tasks and challenges. By observing behavior and experiencing the consequences of behavior over time, a child gradually acquires a set of cognitive scripts for guiding social behavior and a set of emotional regulatory skills for managing physiological arousal. Once formed and stable, those cognitive and emotional “styles” predict behavior over time and across different situations. In this broad, long-term process, coping reactions stand at the nexus of life events and behavioral development—they represent, perhaps more directly and clearly than any other category of behavior, how a child adapts to the demands of the environment and circumstances under which he or she is growing up.

Only recently have researchers begun to test whether the relation over time between exposure to violence and outcomes obtains through the modification of cognitive (e.g., socializing the belief that violence is acceptable; Guerra et al., 2003) or emotional styles (e.g., increasingly dysregulated negative affect; Schwartz & Proctor, 2000). There is research supporting a general dual-process model implicating primarily emotional or primarily cognitive means for understanding the impact of violence on children’s behavioral/mental health (Boxer et al., 2008; Ng-Mak, Salzinger, Feldman, & Steuve, 2004). One process, resting primarily on the development of emotion regulatory functions, might be described as a stress or distress pathway to maladjustment in which experiences with violence promote negative coping and disrupt healthy emotional regulatory styles to produce emotional distress, dysregulation, and associated externalizing difficulties; an array of internalizing symptoms; and, with intense enough exposure, a posttraumatic stress syndrome (Boxer et al., 2008). This pathway thus indicates the net effect of habitual emotional regulatory responses shaped by ineffective or dysfunctional strategies for coping with intense arousal (Boxer et al., 2008; Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers, & Robinson, 2007).

The second pathway, resting primarily on the development of cognitive processing functions, might be termed a normalization or socialization pathway to maladjustment in which experiences with violence promote the development of a cognitive orientation dominated by a hostile interpersonal orientation, acceptance or approval of violence as a means for dealing with arousal and interpersonal issues, and general moral disengagement (Boxer et al., 2008; also see Guerra & Huesmann, 2004). Persistent exposure to violence and repeated engagement in aggressive coping will shape consistent patterns of aggressive response both directly (e.g., normative violence augments beliefs about the acceptability of violence; Guerra et al., 2003) and indirectly (e.g., proximal efforts to cope in certain ways under persistently violent conditions might shape habitual regulatory tendencies and worldviews; Neal, Wood, & Quinn, 2006).

It is relevant to note at this point that, like much of human behavior, coping responses are learned directly and indirectly through observation, with a critical role for parental socialization. As Kliewer and her colleagues have shown (e.g., Kliewer et al., 2006), parents serve as models for as well as active coaches of children’s coping tendencies, in much the same way that parents have been shown to be models of emotion regulation more generally (Eisenberg & Morris, 2002; Eisenberg, Cumberland, & Spinrad, 1998). It is also critical to emphasize here that experiences with violence will not uniformly lead children to maladjustment. Although encounters with violence seem most likely to produce negative forms of coping due to their uncontrollability and, to some extent, unpredictability, certainly many children are exposed to violence with no ill effects accruing from the exposure. Studies have shown that some children are indeed able to utilize positive, constructive forms of coping under conditions of violence exposure to good effect (e.g., Brady, Tschann, Pasch, Flores, & Ozer, 2009; Rosario, Salzinger, Feldman, & Ng-Mak, 2008). Thus, coping style can serve not only as a vulnerability factor, increasing the likelihood of negative outcomes in the context of violence, but also as a protective resource, bolstering resilience under violent conditions.

Coping With Violence and the Resilience Framework

For decades, researchers have acknowledged a critical triad of protective factors in development that have been shown over and over to buffer children against risk under conditions of social and economic disadvantage: (1) personal resources, including temperamental characteristics, cognitive skills, and interpersonal skills; (2) family resources, including warm and consistent parenting as well as general supportiveness; and (3) external supports, including social support from peer and school networks (Garmezy, 1985). These protective factors support or maintain the development of resilience—operationalized as “the process of, capacity for, or outcome of successful adaptation despite challenging or threatening circumstances” (Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990, p. 426). Within this general conception, coping represents an essential component of resilience—coping skills are personal resources, but they also draw from family resources (i.e., with parents as models and coaches for adaptive coping, and providing support when sought through active coping) and external supports (i.e., when those supports are sought through active coping). From the standpoint of fostering resilience through prevention and intervention, coping skills have been a basic, critical target given their amenability to the psychoeducational, group-based approaches in school contexts that have long been staples of mental health promotion programming for children (Dubow et al., 1997; Durlak, 2008; Greenberg, Domitrovich, & Bumbarger, 2001). For example, Lochman’s Coping Power Program has been demonstrated to be a best-practice prevention program for youth beginning to show difficulties with aggressive behavior and the management of angry arousal (Lochman & Wells, 2003). The program utilizes a school-based, small-group structured approach in which coping skills for handling provocation and intense negative arousal are taught via manualized teaching modules. The Children of Divorce Intervention Program has been recognized as a highly effective program for children affected by their parents’ divorce and focuses heavily on teaching children skills for coping with difficult emotions and challenging circumstances (Pedro-Carroll, 2005).

Thus, the role of coping in the framework of resilience generally is crucial—key to understanding how children can demonstrate and sustain resilience, and essential for training and supporting children in becoming resilient. Yet, with respect to coping with violence, the link between specific coping skills and styles and positive outcomes might be difficult to specify, and the broader meaning of “resilience” less clear. Ng-Mak and colleagues (2004) advanced the interesting term pathologic adaptation to describe youth who are highly exposed to violence, who show high levels of antisocial behavior, and who seem to experience little emotional distress. The concept refers to the idea that by experiencing little distress yet engaging in antisocial behavior, those children had adapted pathologically to their circumstances—perhaps also taking on generally approving beliefs about the uses of aggression (Guerra et al., 2003) or disengaging morally from their surroundings (Bandura, 1999).

We believe that this construction or interpretation of children’s functioning runs counter to an elaborated, contextualized understanding of how violence exposure impacts children’s development—and that under conditions of persistent violence exposure, “resilience” may mean something different from what the definition offered by Masten, Best, and Garmezy (1990) has come to indicate. The fundamental issue is what we mean as a field by “successful adaptation”—do we mean optimal positive outcomes such as prosocial behavior, the development of warm and stable interpersonal peer relations, or the acquisition of higher education and secure employment? Certainly, those are laudable goals—but they emanate from a very specific understanding of what it means to be successful. For children growing up in chronically violent conditions—neighborhoods marked by crime, homes marked by domestic disputes, schools marked by hostilities—might “successful” adaptation simply connote survival, a protective peer network, and high school graduation? On one hand, this construction admittedly sets the bar low—but on the other hand, this construction acknowledges that in some contexts it might be more fruitful to investigate and uncover the coping strategies, skills, and styles that simply permit children to “get by” or “get out” unscathed by the potentially devastating slings and arrows of their everyday lives. And in some cases, without a doubt, children in those circumstances will engage in behaviors that to an outsider—the academic in the ivory tower, perhaps—will seem “pathological,” “destructive,” or otherwise negative. But to the insider—from the child’s perspective, or the perspective of his or her parents or others struggling to keep the child safe and secure—those coping reactions, those cognitive, behavioral, and emotional reactions to the stress of violence, might be wholly appropriate and in fact adaptive.

Future Directions for Research and Practice

We agree with Dubow and Rubinlicht’s (2011) observation regarding the problematic absence of literature reporting longitudinal studies of coping strategies and styles—this is certainly the case generally in the coping literature, more so with respect to children’s coping with violence. We think it will be particularly fruitful for developmental scientists to examine the processes linking situational coping reactions to habitual styles of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responding. In so doing, an important bridge will be established linking the rich coping literature to the broader literature on human development invested in understanding how internal and external “inputs” lead over time to stable behavioral “outputs” (Davis-Kean et al., 2008; Huesmann, 1998). Further, we concur with Reid-Quiñones et al. (2011) in their recognition that a more nuanced understanding of children’s coping with various forms of violence is necessary. Our four-dimensional model of violence exposure, reflecting context, content, channel, and chronicity, might serve as a useful framework going forward for researchers interested in specifying and studying various configurations of exposure. Until standardized instruments or protocols are available for fully capturing these dimensions in the context of a clinical assessment, we encourage researchers and clinicians alike to determine logical methods for incorporating various aspects of exposure into their measurement—for example, by modifying response scales and/or item stems for well-established existing instruments.

Finally, given the typical context of violence exposure—that is, its greater likelihood under conditions of poverty and related indicators of depressed socioeconomic status, including ethnic minority status (see Eron, Guerra, & Huesmann, 1997), we share the concern raised by Gaylord-Harden, Cunningham, Holmbeck, and Grant (2010) regarding a great need for research on coping in children from low-income, ethnic minority communities. This might be especially necessary, given recent perspectives concerning the importance of measuring the contexts of children’s coping and evaluating the effectiveness of their chosen strategies and styles for managing the stressors they encounter (Tolan & Grant, 2009). We believe that this is a crucial task in advancing a more complete and socially just understanding of what it means to be “adapted” to persistent violence exposure and the other difficult social conditions that tend to covary with violence exposure.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Preparation of the manuscript was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH085209).

Author Biographies

Paul Boxer is Associate Professor of Psychology and Faculty Fellow in Criminal Justice at Rutgers University in Newark, NJ. He is a clinical-developmental psychologist who studies the development of antisocial behavior and the impact of violence on mental health in different social environments.

Elizabeth Sloan-Power isAssistant Professor of Social WorkatRutgers University in Newark, NJ. She studies links between coping and health under difficult social conditions including chronic violence and poverty.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

We use the terms children and children and adolescents (and various forms of those terms) interchangeably throughout this article to reduce redundancy and to reflect the fact that the bulk of the empirical literature on children’s exposure to violence is based on self-report data from youth in the age range of late childhood (i.e., about 8–10 years) through middle adolescence (about 14–17 years).

References

- Anderson CA, Berkowitz L, Donnerstein E, Huesmann LR, Johnson JD, Linz D, Malamuth N, & Wartella E (2003). The influence of media violence on youth. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 81–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3, 193–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorck JP, & Cohen LH (1993). Coping with threats, losses, and challenge. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 12, 36–72. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Edwards-Leeper L, Goldstein SE, Musher-Eizenman D, & Dubow EF (2003). Exposure to “low-level” aggression in school: Associations with aggressive behavior, future expectations, and perceived safety. Violence and Victims, 18, 691–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Goldstein SE, Musher-Eizenman D, Dubow EF, & Heretick D (2005). Developmental issues in the prevention of school aggression from the social-cognitive perspective. Journal of Primary Prevention, 26, 383–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Morris AS, Terranova AM, Kithakye M, Savoy SC, & McFaul A (2008). Coping with exposure to violence: Relations to aggression and emotional symptoms in three urban samples. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 17, 881–893. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Huesmann LR, Dubow EF, Landau S, Gvirsman SD, Shikaki K, & Ginges J (2012). Exposure to violence across the social ecosystem and the development of aggression: A test of ecological theory in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Child Development, 84, 163–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Sloan-Power E, Mercado I, & Schappell A (2011). Coping with stress, coping with violence: Links to mental health outcomes among at-risk youth. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 34, 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, & Terranova AM (2008). Effects of multiple maltreatment experiences among psychiatrically hospitalized youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 32, 637–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Terranova AM, Savoy SC, & Goldstein SE (2008). Developmental issues in the prevention of aggression and violence in school In Miller T (Ed.), School violence and primary prevention. (pp. 277–294) New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Brady SS, Tschann JM, Pasch LA, Flores E, & Ozer EJ (2009). Cognitive coping moderates the association between violent victimization by peers and substance use among adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34, 304–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt R, Ward CL, Dawes A, & Flisher AJ (2005). Epidemiological measurement of children’s and adolescents’ exposure to community violence: Working with the current state of the science. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 8, 327–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Stichik TL, Birdthistle I, & Earls FJ (2001). Youth exposure to violence: Prevalence, risks, and consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 71, 298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushman BJ, & Huesmann RL (2006). Short-term and long-term effects of violent media on aggression in children and adults. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 160, 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Causey DL, & Dubow EF (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, & Wadsworth ME (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Progress, problems, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, & Compas BE (2004). Coping as a moderator of relations between reactivity to interpersonal stress, health status, and internalizing problems. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 28, 347–368. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, & Dodge KA (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg L, & Krug E (2002). “Violence: A Global Health Problem” In Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, Zwi A, & Lozano R (Eds.), World Report on Violence and Health (pp. 3–21). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Kean PE, Huesmann LR, Jager J, Collins WA, Bates JE, & Lansford J(2008). Changes inthe relationof beliefs and behaviors during middle childhood. Child Development, 79, 1257–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey M (2002). Negative coping as mediator in the relation between violence and outcomes: Inner-city African American youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72, 102–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Bates JE, & Pettit GS (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, & Pettit GS (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39, 349–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Huesmann LR, & Boxer P (2009). A social-cognitive-ecological framework for understanding the impact of exposure to persistent ethnic-political violence on children’s psychosocial adjustment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 12, 113–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Pargament KI, Boxer P, & Tarakeshwar N (2000). Initial investigation of Jewish early adolescents’ ethnic identity, stress, and coping. Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 418–441. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Roecker CE, & D’Imperio R (1997). Mental health In Ammerman RT & Hersen M (Eds.), Handbook of prevention and treatment with children and adolescents: Interventions in the real world context (pp. 238–258). New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, & Rubinlicht M (2011). Coping In Brown BB & Prinstein M (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 109–118). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA (2008). Prevention In Gutkin T & Reynolds C (Eds.), Handbook of school psychology (4th ed, pp. 2377–2418). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, & Spinrad TL (1998). Parental socialization of emotion. Psychological Inquiry, 9, 241–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, & Morris AS (2002). Children’s emotion-related regulation In Reese H & Kail R (Eds.), Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 30, 189–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eron LD, Guerra NG, & Huesmann LR (1997). Poverty and violence In Feshbach S & Zagrodzka J (Eds.), Aggression: Biological, developmental, and social perspectives (pp. 139–154). New York, NY: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Eth S, & Pynoos RS (1994). Children who witness the homicide of a parent. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 57, 287–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, & Turner HA (2007). Polyvictimization: A neglected component in child victimization trauma. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 7–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormrod RK, & Hamby SL (2010). Trends in childhood violence and abuse exposure: Evidence from two national surveys. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164, 238–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DJ, Wester KL, & Singer MI (2004). Impact of exposure to violence in school on child and adolescent mental health and behavior. Journal of Community Psychology, 32, 559–573. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 839–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura A, & Jacques AJ (2009). Community violence: A meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 227–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N (1985). Stress-resistant children: The search for protective factors In Stevenson JE (Ed.). Recent research in developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (Book Supplement No. 4, pp. 213–233). Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden N, Cunningham JA, Holmbeck GN, & Grant KE (2010). Suppressor effects in coping research with African American adolescents from low-income communities. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 843–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SE, Young A, & Boyd C (2008). Relational aggression at school: Associations with school safety and social climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 641–654. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M, Domitrovich C, & Bumbarger B (2001). The prevention of mental disorders in school-aged children: Current state of the field. Prevention and Treatment, 4, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, & Huesmann LR (2004). A cognitive-ecological model of aggression. International Review of Social Psychology, 17, 177–203. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra NG, Huesmann LR, & Spindler A (2003). Community violence exposure, social cognition, and aggression among urban elementary school children. Child Development, 74, 1507–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guterman NB, Cameron M, & Staller K (2000). Definitional and measurement issues in the study of community violence among children and youths. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 571–587. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, & Moylan CA (2008). Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 9, 84–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden GW, Geffner R, & Jouriles EN (Eds.). (1998). Children exposed to marital violence: Theory, research, and applied issues. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Howard DE (1996). Searching for resilience among African-American youth exposed to community violence: Theoretical issues. Journal of Adolescent Health, 18, 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huesmann LR (1998). The role of social information processing and cognitive schemas in the acquisition and maintenance of habitual aggressive behavior In Geen RG & Donnerstein E (Eds.), Human aggression: Theories, research, and implications for policy (pp. 73–109). New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes H, Parkinson D, & Vargo M (1989). Witnessing spouse abuse and experiencing physical abuse: A “double whammy”? Journal of Family Violence, 4, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Jaycox LH, Stein BD, Kataoka SH, Wong M, Fink A, Escudero P, & Zaragoza C (2002). Violence exposure, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depressive symptoms among recent immigrant schoolchildren. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1104–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR, & Kenny ED (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 71, 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Parrish KA, Taylor KW, Jackson K, Walker JM, & Shivy VA (2006). Socialization of coping with community violence: Influences of caregiver coaching, modeling, and family context. Child Development, 77, 605–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen K, Räsänen E, Henttonen I, Almqvist F, Kresanov K, & Linna SL, … Tamminen T (1998). Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22, 705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuther TL, & Wallace SA (2003). Community violence and sociomoral development: An African American cultural perspective. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 73, 177–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, & Wells KC (2003). The coping power program for preadolescent aggressive boys and their parents: Effects at the one-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M (2003). Consequences of children’s exposure to community violence: Implications for understanding risk and resilience. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 499–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, & Gordis E (2000). The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology, 5, 445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, & Garmezy N (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Mazza JJ, & Overstreet S (2000). Children and adolescents exposed to community violence: A mental health perspective for school psychologists. School Psychology Review, 29, 86–101. [Google Scholar]

- Morris AS, Silk JS, Steinberg L, Myers SS, & Robinson LR (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16, 361–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, Loosier PS, & Windle M (2008). Violence exposure across multiple contexts: Individual and joint effects on adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78, 70–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DT, Wood W, & Quinn JM (2006). Habits—A repeat performance. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- Netland M (2001). Assessment of exposure to political violence and other potentially traumatizing events: A critical review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 311–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng-Mak DS, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, & Steuve CA (2004). Pathologic adaptation to community violence among inner-city youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 74, 196–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro-Carroll JL (2005). Fostering children’s resilience in the aftermath of divorce: The role of evidence-based programs for children. Family Court Review, 43, 52–64. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak Seth D. (2008). Mechanisms linking early experience and the emergence of emotions: Illustrations from the study of maltreated children. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 370–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid-Quiñones K, Kliewer W, Shields BJ, Goodman K, Ray MH, & Wheat E (2011). Cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to witnessed versus experienced violence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, & Ng-Mak DS (2008). Intervening processes between youths’ exposure to community violence and internalizing symptoms over time: The roles of social support and coping. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41, 43–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, & Cohen LJ (1986). Approach, avoidance, and coping with stress. American Psychologist, 41, 813–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, & Shelley GA (2002). Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ (1991). The social context of development In Woodhead M, Carr R, & Light P (Eds.), Becoming a person (pp. 167–189). Florence, KY: Taylor & Francis/Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sameroff AJ (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81, 6–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, & Haden SC (2006). Community violence victimization and aggressive behavior: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 502–515. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Collins RL, Marshall GN, & Elliott MN, … Berry SH (2001). A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine, 345, 1507–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, & Proctor LJ (2000). Community violence exposure and children’s social adjustment in the school peer group: The mediating roles of emotion regulation and social cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 670–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terranova AM, Boxer P, & Morris AS (2010). Responding to peer victimization in middle childhood: What is a victim to do? Journal of Aggression: Conflict and Peace Research, 2, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, & Tabone JK (2010). The impact of early maltreatment on behavioral trajectories. Child Abuse and Neglect, 34, 907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, Gorman-Smith D, Henry D, Chung K, & Hunt M (2002). The relation of patterns of coping of inner-city youth to psychopathology symptoms. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12, 423–449. [Google Scholar]

- Tolan PH, & Grant K (2009). How social and cultural contexts shape the development of coping: Youth in the inner-city as an example In Skinner EA & Zimmer-Gembeck MJ (Eds.), Coping and the development of regulation. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 124, 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, Durán L, & Horn JL (2003). Community violence as it affects child development: Issues of definition. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 6, 223–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, & Ormrod RK (2010). Polyvictimization in a national sample of children & youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 38, 323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, McCabe MA, & Denning MD (1994). Primary and secondary control among children undergoing medical procedures: Adjustment as a function of coping style. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra ML, Diener-West M, Markow D, Leaf PJ, Hamburger M, & Boxer P (2008). A national study examining linkages between media violence and seriously violent behavior among adolescents. Pediatrics, 122, 929–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]