Abstract

Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome in the context of severe sepsis and septic shock represents a serious clinical disorder. A recent case series in patients with septic shock and renal failure receiving hemoadsorption treatment showed rapid hemodynamic stabilization and increased survival, particularly in pneumonia patients and in those where therapy was started early. We hypothesized that patients suffering from pneumonia and refractory acute respiratory distress syndrome to the extent that they required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support could possibly demonstrate the most pronounced benefit from the treatment.

Methods

We assessed the association of hemoadsorption treatment with hemodynamics, ventilation, and outcome variables in a set of patients with septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, need for veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and continuous renal replacement therapy.

Results

Key observations include a significant stabilization in hemodynamics as evidenced by a marked decrease in catecholamine need, which was paralleled by a clear reduction in hyperlactatemia. Respiratory variables improved significantly. In addition, severity of illness and overall organ dysfunction showed a considerable decrease during the course of treatment. Observed mortality was approximately half as predicted by APACHE II. Treatment with CytoSorb was safe and well tolerated with no device-related adverse events.

Discussion

This is the first case series reporting on outcome variables associated to CytoSorb therapy in critically ill patients with septic shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and continuous renal replacement therapy. Based on our observations in this small case series, CytoSorb might represent a potentially promising therapy option for patients with refractory extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-dependent acute respiratory distress syndrome in the context of septic shock.

Keywords: Acute respiratory distress syndrome, continuous renal replacement therapy, CytoSorb, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, hemoadsorption, septic shock

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a serious clinical disorder characterized by severe impairment of gas exchange, while most common causes are pneumonia, sepsis, and acute pancreatitis. The progression to ARDS can be rapid and is often associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality (46%),1depending on the underlying disease and the severity of the disease pattern. Despite substantial progress in elucidating the mechanisms of ARDS,2there has been little advancement in developing effective treatments and no specific treatment exists other than to provide supportive therapy. To date, causal therapy means treatment of the underlying decompensating factors causing the ARDS. Additionally, lung-protective mechanical ventilation using low tidal volumes (thereby limiting inspiratory pressures) and intermittent prone positioning can reduce mortality in cases of severe ARDS.3

In extreme life-threatening cases, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can represent a life-saving alternative to treat ARDS and refractory hypoxemia, to stabilize gas exchange, and to serve as a temporary replacement of pulmonary function and bridge for recovery. Recent evidence from a large multicentric, randomized trial suggested a potential positive effect of the use of veno-venous (VV) ECMO in refractory ARDS in terms of mortality and complications.4Newest improvements for VV-ECMO applications provide the full spectrum of extra-pulmonary lung support, from efficient carbon dioxide removal to complete oxygenation. Hence, these novel techniques should be used in patients with massively impaired ventilation variables (e.g., low PaO2/FiO2index) who cannot be conventionally ventilated in a lung-protective manner (despite low tidal volumes, prone positioning, and adequately adapted positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP)).

Recently, hemoadsorption with a new device (CytoSorb) has been developed for use in the treatment of systemic hyperinflammation, associated with sepsis and ARDS. Beneficial effects of the device in combination with ECMO-treated ARDS have been reported in a number of anecdotal case reports.5–7A recent case series from our institution, conducted in 26 critically ill patients with septic shock and need for renal replacement therapy receiving treatment with CytoSorb, showed rapid hemodynamic stabilization and increased survival compared to predicted mortality, particularly in patients where therapy was started early. In addition, from this patient population, medical patients (predominantly pneumonia) seemed to benefit more than post-surgical patients in terms of survival.8

We hypothesized that patients suffering from pneumonia and refractory ARDS, to the extent that they required ECMO support, could possibly demonstrate the most pronounced benefit from the treatment. We therefore included patients with refractory ECMO-dependent ARDS as well as renal replacement therapy in the context of septic shock into our case series (n = 7) and assessed the association of CytoSorb hemoadsorption with hemodynamics and clinically relevant outcome variables.

Methods

This case series was carried out at the surgical–medical intensive care unit of Emden hospital, Germany. All patients or their relatives signed an informed consent for retrospective data evaluation. Consecutive patients with the diagnosis of septic shock due to pneumonia in combination with severe ARDS were included. Of note, the present case series represents new data including new patients (n = 4) as well as data from our previous case series (n = 3) which met the criteria for inclusion.8Patients with septic shock were identified using the inclusion criteria described by Bernard et al.9Initial therapy of these patients followed the Surviving Sepsis guidelines.

Patients with ARDS were identified following the Berlin definition.10,11Initial ventilation was performed in a lung-protective manner11,12including prone positioning for at least 16 h.13If the initial ventilation settings failed to increase the Horovitz index above 150 mmHg after 24 h (corresponding to ELSO criteria), VV-ECMO was indicated and installed. We utilized a Novalung iLA activve with an XLung membrane Kit (Extracorporeal Gas Exchange Kit, Novalung) to achieve blood flow rates above 3 L/min. Anticoagulation was achieved using an intravenous heparin infusion to reach a PTT of 50 to 60 s.

One of the additional organ failures had to be acute kidney injury (AKI) necessitating renal replacement therapy. These criteria had to be fulfilled despite maximum standard therapy including adequate fluid resuscitation (following KDIGO guidelines),14differentiated catecholamine therapy including administration of norepinephrine to achieve a mean arterial pressure (MAP) >60 mmHg, antibiotics at least 1 h after detection of septic shock (see Table 1for administered antibiotics), and lung-protective ventilation. If the demand for norepinephrine could not be reduced even after additional corticoid administration, and if the patient met the minimum AKI stage II criteria (serum creatinine 2.0–2.9 times baseline, urine output <0.5 ml/kg/h for ≥12 h), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) in combination with CytoSorb therapy was then commenced. CRRT was performed in continuous hemodialysis (CVVHD) mode with citrate anticoagulation (Multifiltrate CiCa; Fresenius Medical Care). A CytoSorb adsorber (CytoSorbents Europe GmbH, Germany) was then installed into the CRRT circuit in a pre-hemofilter position (AV1000; Fresenius Medical Care). Blood flow rates were kept between 100 and 150 mL/min. All patients received a minimum of three CytoSorb treatments with additional treatments according to the intensivist’s judgment. Adsorbers were changed every 24 h or every 12 h if there was no or only a minimal effect within a certain amount of time (decrease of <20% in catecholamine-demand within the first 24 h of CytoSorb application). The number of treatments is depicted in Table 1. CytoSorb was not installed at any time into the VV-ECMO circuit and was run only in conjunction with a separate CRRT circuit. Therefore, CytoSorb treatment was not performed after CRRT discontinuation.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics, treatment modalities, scoring pre- and post-treatment, clinical parameters, and patient outcome.

| Case no. | Sex | Age | Major medical history/comorbidities | Source | APACHE II | Abx | CytoSorb treatments (n) | Delay (h) | SAPS pre | SAPS post | SOFA pre | SOFA post | Cat- free days | CRRT (days) | Ventilation (days) | ECMO (days) | Hospital stay (days) | ICU stay (days) | Predicted mortality | 28-day mortality | ICU mortality | Hospital mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 46 | Hypertension, hypertensive cardiac disease, global heart failure | Pneumonia | 44 | Piperacillin/ Tazobactam | 3 | 50 | 38 | 40 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 97.1 | YES | YES | YES |

| 2 | M | 51 | Epilepsy, psychosis, nicotine abuse | Pneumonia | 42 | Piperacillin/ Tazobactam | 6 | 24 | 47 | 46 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 12 | 13 | 7 | 14 | 13 | 93.9 | YES | YES | YES |

| 3 | M | 41 | Alcohol addiction, pancreatitis | Pneumonia/ pancreatitis | 39 | Meropenem | 3 | 24 | 51 | 47 | 11 | 10 | 15 | 18 | 27 | 14 | 36 | 36 | 90.8 | NO | NO | NO |

| 4 | M | 50 | Alcohol addiction | Pneumonia | 38 | Meropenem/ Fosfomycin | 7 | 24 | 58 | 43 | 15 | 10 | 37 | 7 | 57 | 10 | 57 | 57 | 89.5 | NO | NO | NO |

| 5 | M | 45 | Alcohol addiction, pancreatitis, arterial hypertension, Ulcus ventriculi, adipositas | Pneumonia/ pancreatitis | 28 | Meropenem | 4 | 24 | 33 | 28 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 3 | 17 | 10 | 27 | 20 | 66.5 | NO | NO | NO |

| 6 | M | 65 | COPD, arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, adipositas, aortic valve replacement, transcerebral ischemia, diabetes mellitus type 2, chronic renal failure grade 2 | Pneumonia | 33 | Piperacillin/ Tazobactam | 3 | 24 | 49 | 48 | 14 | 13 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 87 | YES | YES | YES |

| 7 | M | 64 | COPD, chronic renal failure grade 2, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, chronic pulmonary heart disease | Pneumonia | 56 | Piperacillin/ Tazobactam | 3 | 24 | 57 | 39 | 12 | 12 | 31 | 11 | 37 | 11 | 40 | 40 | 99.5 | NO | NO | NO |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ICU: intensive care unit; SAPS: Simplified Acute Physiology Score; SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Patients excluded from analysis were those who were pregnant or breast-feeding, age <18 years, conditions with a poor 28-day chance of survival because of an uncorrectable medical condition such as poorly controlled neoplasm, or other moribund end-stage disease states in which death was perceived to be imminent.

To evaluate the effects of the combined CRRT/CytoSorb/VV-ECMO treatment, we calculated or collected Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS-2) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores, the demand for norepinephrine to achieve a certain MAP (µg/h·mmHg−1), and assessed blood lactate levels as well as ventilation variables (PEEP, PaO2/FiO2, P max), before and after completion of treatment. We also assessed catecholamine-free days (in relation to ICU days) and length of extracorporeal organ support (mechanical ventilation, CRRT, and VV-ECMO days). Intensive care and hospital lengths of stay as well as ICU, 28-day, and hospital survival were recorded as outcome variables.

IBM SPSS Statistics 25 (SPSS Inc. to IBM Company, Chicago, IL) was used to perform the statistical analysis assuming a conventional 5% level of significance. Alpha adjustment for multiple testing was not applied; therefore, the results have a purely descriptive or exploratory character.

Results

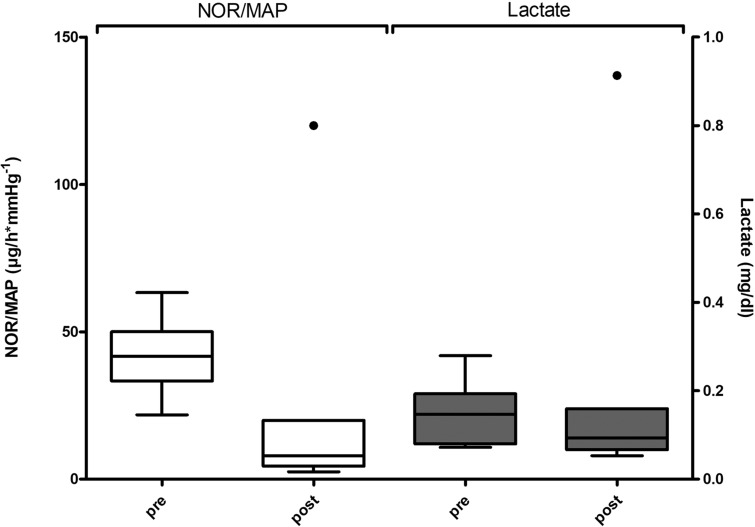

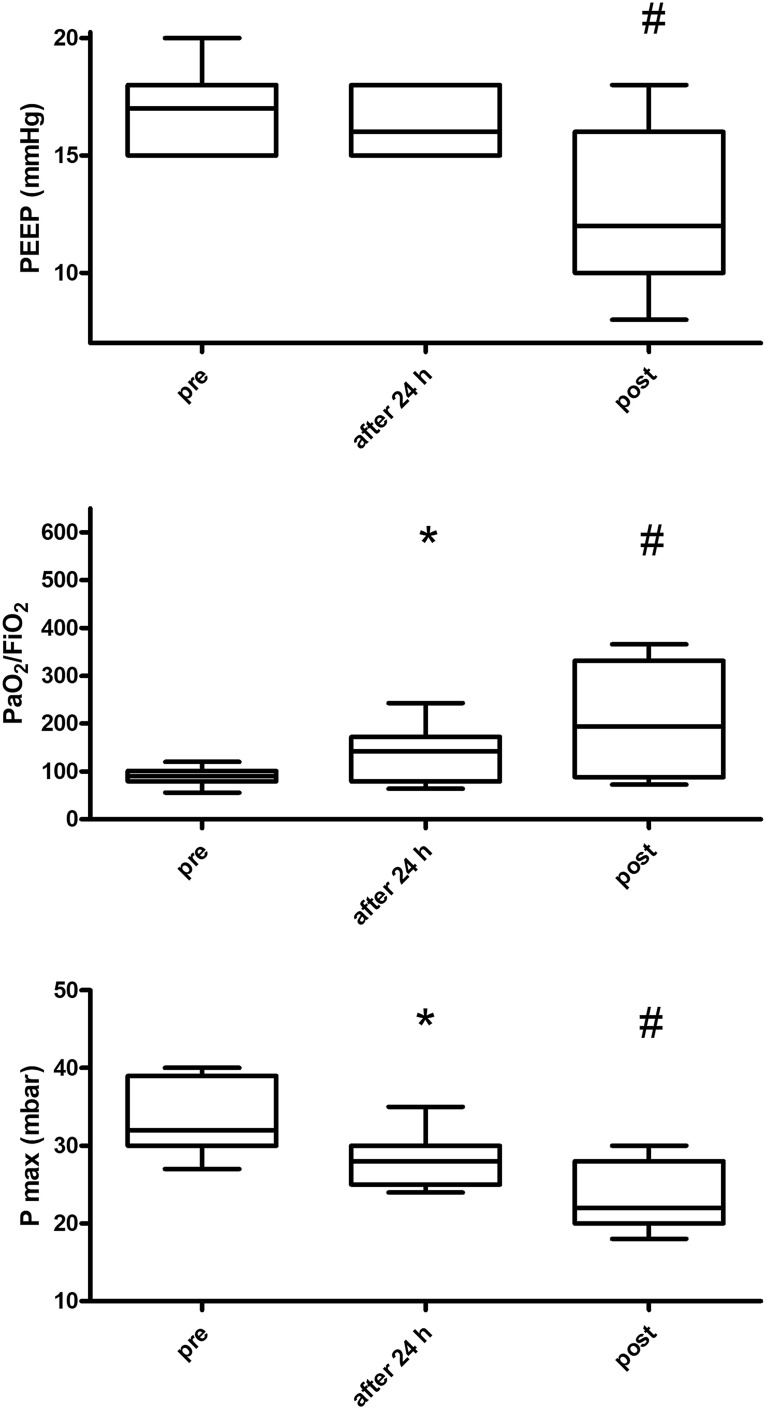

Data from seven consecutive patients treated between October 2014 and April 2017 with the combined therapy of CytoSorb, CRRT, and ECMO fulfilling inclusion criteria as outlined before were evaluated. All patients suffered from sepsis of a medical etiology, with pneumonia being the main infectious source. Two patients had pneumonia accompanied by pancreatitis. Patient characteristics, major medical history, and antibiotic therapy details are depicted in Table 1. On admission to ICU, the median APACHE II score was 39 (range: 28–56), with a calculated predicted mortality of 90.8%. All patients received at least three CytoSorb treatments as well as additional treatments (up to 7) depending on their clinical response (Table 1). Median number of CytoSorb treatments in this population was 3, while median treatment time equaled 24 h per adsorber. We observed a clear stabilization in hemodynamics as demonstrated by a marked decrease in catecholamine need, calculated as the demand for norepinephrine necessary to achieve a certain MAP by dividing the norepinephrine dose (µg/h) by the MAP (mmHg) measured at the same time point as has been described and published before.8Catecholamine need was reduced from a median of 41.6 (range: 21.8–63.3) pre-treatment to 8 (range: 2.5–120) µg/h·mmHg−1post-treatment (81% reduction, not statistically significant, p = 0.237) (Figure 1). Hemodynamic stabilization was paralleled by a decrease in blood lactate levels when comparing median levels before (22 mg/dl, range: 10.8–41.9) and after (14 mg/dl, range: 8–137) treatment, representing a decrease of 36%, which was, however, not statistically significant, p = 0.236 (Figure 1). Regarding ventilation variables, we observed a clear and steady improvement during the course of treatment, reaching statistical significance as indicated in Figure 2. As such, a reduction of 30% in PEEP could be achieved comparing pre- and post-treatment levels (from a median of 17 to 12 cm H2O, range: pre = 15–20, range: post = 8–18). Horovitz index (PaO2/FiO2) could be increased by 117% (pre = 89 mmHg to post = 194 mmHg, range: pre = 55.5–120, range: post = 72.3–366). P max was reduced from a median of 32 to 22 mbar (range: pre = 27–40, range: post = 18–30) which equaled a 32% reduction (Figure 2). We further observed a decrease in SAPS II (decrease of 12.2%) and SOFA-scores (decrease of 14.3%) in our patients. Observed mortality (42.85%, 3 of 7 patients) was approximately half as predicted by APACHE II (90.8%). There were no CytoSorb device-related adverse events or problems running the adsorber in conjunction with the two additional extracorporeal treatments.

Figure 1.

Effect of CytoSorb hemoadsorption on hemodynamics and blood lactate levels. Demand of norepinephrine to achieve a certain MAP (µg/h·mmHg−1) before (pre) and after (post) as well as blood lactate levels (mg/dl) before (pre) and after (post) treatment. Depicted are Tukey boxplots with equal whisker lengths of 1.5 IQR for both whiskers. Dots represent outliers. There was no statistical significance for NOR/MAP (p = 0.237) and lactate (p = 0.236) applying Wilcoxon test for pair differences.

Figure 2.

Effect of CytoSorb hemoadsorption on ventilatory and lung function variables. Course of ventilatory and lung function variables (i.e. PEEP, PaO2/FiO2, P max) before (pre), during (24 h) and after (post) treatment. Depicted are Tukey boxplots with equal whisker lengths of 1.5 IQR for both whiskers. Dots represent outliers; * indicates statistical difference of timepoint after 24 h compared to pre-treatment levels, while #indicates statistical difference of post-treatment levels compared to pre-treatment levels applying t-test for connected samples.

Discussion

VV extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an increasingly used and life-saving technology to treat patients with ARDS and refractory hypoxemia in the context of pneumonia and sepsis. All of these conditions are per se associated with an activation of the body’s immune system and can result in an overwhelming inflammatory response characterized by highly elevated pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels, which may ultimately lead to multiple organ damage and failure. Controlling these excessively increased levels of inflammatory mediators using CytoSorb hemoadsorption may be considered a valuable treatment option. A recent case series confirmed that medical patients with pneumonia showed a superior response in terms of hemodynamic stabilization and survival when compared to surgical patients, leading us to test the hypothesis of whether extremely sick patients with pneumonia/ARDS, who required ECMO support, would benefit even more from the treatment. In this retrospective case series, we investigated the use of CytoSorb hemoadsorption to treat seven consecutive patients with septic shock, ARDS, need for VV ECMO, and renal replacement therapy. Key observations include a significant stabilization in hemodynamics as evidenced by a marked decrease in catecholamine need which was paralleled by a clear reduction in hyperlactatemia. Respiratory variables, all representatives of lung function and vital for lung-protective ventilation (i.e. PEEP, PaO2/FiO2, P max), improved significantly. In addition, treatment was associated with a reduction in severity of illness and overall organ dysfunction measured by SAPS and SOFA, respectively. Observed mortality was approximately half than the one predicted by APACHE II.

We chose this set of patients based on the insights we gained from our previous study showing that medical patients with pneumonia seemed to benefit more than post-surgical patients in terms of survival, which was associated with a hospital mortality in 60% of pneumonia patients in this recently published study (predicted mortality by APACHE II 87%).8We expanded these observations assuming that even sicker patients, suffering from pneumonia and refractory ARDS requiring ECMO support, could possibly demonstrate the most pronounced benefit from the treatment. Indeed and despite the greater predicted mortality as well as higher initial SOFA and APACHE II scores in this subgroup treated herein, we observed a survival benefit in these extremely sick patients, demonstrated by the in-hospital mortality of 42.85% vs. 60% when compared to a similar subgroup (pneumonia, therapy delay <24 h, CytoSorb, without refractory ARDS and ECMO) from our previous study.8At this time, we can only speculate as to the underlying mechanisms and why pneumonia patients seem to benefit most. However, in these patients direct infectious source control by surgical measures is not possible which is different from a direct surgical approach in patients with, e.g., an abdominal focus. This can be regularly observed in patients who need to be treated using conservative measures only (e.g., with meningitis or urosepsis), generally showing better survival in septic shock.15Moreover, poorly perfused tissues (especially necrotic tissues and abscesses) are difficult to access for antibiotics (e.g., diabetic foot, necrotizing fasciitis) and are therefore more challenging to control using antibiotic regimens.16In these cases, surgical intervention eradicating the focus still represents the most important and decisive measure. Therefore, hemoadsorption might potentially have a bigger impact in medical patients (e.g., pneumonia), due to a lack of treatment options (besides antibiotics, fluid and catecholamine therapy) when compared to patients with an abdominal focus.

We further observed a clear reduction in SOFA and SAPS scores during the course of treatment, which is in contrast with our recent results8and to the latest study by Friesecke et al. conducted in a subset of patients with refractory septic shock.17This observation is most probably due to the extended observation period applied in this new case series with a median of seven days, giving time for manifestation of therapy effects at the organ level and consequently on SOFA score.

The patients treated in this study suffered from refractory ARDS as their most prominent organ failure (along with renal failure); therefore, we targeted variables that allow for general conclusions on the improvement in lung function and possibility to reduce invasiveness of ventilation. We found that all the variables determining invasiveness of ventilation (i.e. PEEP, P max) improved. An improvement in PaO2/FiO2is associated with a faster reduction in ventilation pressures (P max and PEEP) and more rapid weaning from the ventilator in general. In turn, this might potentially lead to a reduction in ventilator-associated infections or deaths.18–20Interestingly, this pattern was observed as early as within 24 h after the commencement of CytoSorb therapy. That might in part be due to the fact that the immunological/inflammatory picture in ARDS is largely independent of the underlying cause of the syndrome,21and thus, cytokine adsorption could actually influence inflammation of various origin.

Inflammatory processes are involved in the development of ARDS and also in the impairment of lung function. Cytokines play a central role in the inflammatory process, which, however, is also aggravated by other mediators such as damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS). Some DAMPS (e.g., C5a, HMGB1) have been shown to be effectively removed from whole blood by CytoSorb.22Moreover, controlling the inflammatory response using hemoadsorption therapy may have a positive impact on the endothelial glycocalix and may also be beneficial for maintaining the vascular barrier function which plays a pivotal role in the development of oxygen mismatch and tissue edema. In this context, case reports have shown a reduction in extravascular lung water with CytoSorb therapy, pointing toward a stabilization in pulmonary capillary integrity. This was also supported in the article by David et al.23who stated that the relatively low absolute cytokine levels before start of removal therapy make one consider the fact that endothelial improvement might be due to the removal of permeability-inducing factors other than cytokines. Therefore, the effect of CytoSorb therapy cannot be narrowed down to the sole removal of cytokines and is potentially rather the result of a removal of a larger armamentarium of different substances.

Beyond that, ECMO by itself might trigger inflammatory responses (via extracorporeal circuit, pump, and artificial surfaces), which can further aggravate the clinical course. CytoSorb might have the beneficial effects with regard to a prevention/modulation of such responses as likewise shown in several studies after cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) exhibiting similar clinical features.24

An optimally adapted PEEP offers advantages for survival in ARDS.20,25Therefore, the more rapid reduction in PEEP combined with an increasing Horovitz quotient, as a marker for progressive improvement in lung function, might be assumed to be a criterion for potential improvement in the clinical situation with hemoadsorption therapy.

We observed a hemodynamic stabilization, accompanied by a concomitant reduction in norepinephrine doses. Of note, improvement in macro-hemodynamics is only valuable if it translates to the microcirculatory level. Lactate is a surrogate for the resolution of global tissue hypoxia26and an improvement of lactate clearance reflects improved microcirculation and tissue perfusion. On the other hand, a lack of appropriate lactate clearance (at best within the first 6–24 h) in severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with poor outcome.26,27A recently published randomized, controlled, open-label, multicenter trial, conducted from 2008 to 2011, reported on the use of CytoSorb for 6 h daily for 7 days in 97 mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis or septic shock and acute lung injury or ARDS.28The purpose of this study was to provide the first clinical confirmation of safety and efficacy (i.e. cytokine removal) of the CytoSorb device. Both of these aims were met, whereas, based on today`s knowledge and experience, the study design was not suitable to show any impact of the therapy on clinical outcome.

In our patients, we witnessed an effective reduction in blood lactate levels. These findings are therefore consistent with previous clinical data showing that hemodynamic stabilization, decreasing vasopressor requirements, and improving lactate clearance in the setting of septic shock and post-CPB SIRS are obviously the primary clinical manifestations associated with hemoadsorption using CytoSorb.5,17,24,29,30

Limitations

We believe there are several limitations associated with this case series, which have to be considered in the design of future studies. A significant limitation is the small number of cases in a heterogenous group of patients. However, since we included consecutive patients fulfilling our quite stringent enrollment criteria, the results drawn from this case series show hypothesis-generating trends and should as such be of considerable value for planning upcoming trials. Second, the multimodal treatment approach (i.e. CytoSorb, CVVHD, VV-ECMO, antibiotics, vasopressors etc.) to treat these complex patients prevents us from ascribing the patient’s positive outcome to any one treatment modality. Another limitation is the difference in treatment time in patients, not allowing us to draw potential conclusions in terms of dosing and timing. Finally, we did not perform cytokine measurements, as these are not routinely measured in our institution. However, measurement of cytokines (foremost IL-6) is critical for upcoming major trials.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case series on the use of CytoSorb therapy in critically ill patients with septic shock, ARDS, and need for VV ECMO as well as renal replacement therapy. The combined treatment of these patients was associated with a significant stabilization of hemodynamics and a clear reduction in hyperlactatemia. We further observed a significant improvement in lung function and invasiveness of ventilation. Additionally, severity of illness and overall organ dysfunction showed a considerable decrease during the course of the combined treatment, while observed mortality was only half as predicted by APACHE II. Therefore, CytoSorb might represent a potentially promising therapy option for patients with refractory ECMO-dependent ARDS in the context of septic shock, which needs to be validated in well-designed future trials.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: KK and MD have received honoraria for lectures from Cytosorbents. The other authors have no conflicts of interest associated with this report.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology, patterns of care, and mortality for patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in intensive care units in 50 countries. JAMA 2016; 315: 788–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blondonnet R, Constantin JM, Sapin V, et al. A pathophysiologic approach to biomarkers in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Dis Markers 2016; 2016: 3501373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonelli AR, Zein J, Adams J, et al. Effects of interventions on survival in acute respiratory distress syndrome: an umbrella review of 159 published randomized trials and 29 meta-analyses. Intensive Care Med 2014; 40: 769–787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peek GJ, Mugford M, Tiruvoipati R, et al. Efficacy and economic assessment of conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 1351–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruenger F, Kizner L, Weile J, et al. First successful combination of ECMO with cytokine removal therapy in cardiogenic septic shock: a case report. Int J Artif Organs 2015; 38: 113–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Träger K, Schütz C, Fischer G, et al. Cytokine reduction in the setting of an ARDS-associated inflammatory response with multiple organ failure. Case Rep Crit Care 2016; 2016: 9852073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lees NJ, Rosenberg A, Hurtado-Doce AI, et al. Combination of ECMO and cytokine adsorption therapy for severe sepsis with cardiogenic shock and ARDS due to Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia and H1N1. J Artif Organs 2016; 19: 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kogelmann K, Jarczak D, Scheller M, et al. Hemoadsorption by CytoSorb in septic patients: a case series. Crit Care 2017; 21: 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernard GR, Vincent JL, Laterre PF, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human activated protein C for severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 699–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012; 307: 2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 1573–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amato MB, Barbas CS, Medeiros DM, et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 1998; 338: 347–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guérin C, Reignier J, Richard JC, et al. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 2159–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.KDIGO AKI Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for acute kidney injury. Kidney Int Suppl 2012; 2: 1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001; 29: 1303–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tessier JM, Scheld WM. Principles of antimicrobial therapy. Handb Clin Neurol 2010; 96: 17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Friesecke S, Stecher SS, Gross S, et al. Extracorporeal cytokine elimination as rescue therapy in refractory septic shock: a prospective single-center study. J Artif Organs 2017; 20: 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boles JM, Bion J, Connors A, et al. Weaning from mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J 2007; 29: 1033–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 2002; 287: 345–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amato MB, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocco PR, Dos Santos C, Pelosi P. Lung parenchyma remodeling in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Minerva Anestesiol 2009; 75: 730–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gruda M. In vitro adsorption of a broad spectrum of inflammatory mediators with CytoSorb® hemoadsorbent polymer beads. Critical Care 2016; 20: P194. [Google Scholar]

- 23.David S, Thamm K, Schmidt BMW, et al. Effect of extracorporeal cytokine removal on vascular barrier function in a septic shock patient. J Intensive Care 2017; 5: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Träger K, Fritzler D, Fischer G, et al. Treatment of post-cardiopulmonary bypass SIRS by hemoadsorption: a case series. Int J Artif Organs 2016; 39: 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briel M, Meade M, Mercat A, et al. Higher vs lower positive end-expiratory pressure in patients with acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2010; 303: 865–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nguyen HB, Rivers EP, Knoblich BP, et al. Early lactate clearance is associated with improved outcome in severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 1637–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marty P, Roquilly A, Vallée F, et al. Lactate clearance for death prediction in severe sepsis or septic shock patients during the first 24 hours in Intensive Care Unit: an observational study. Ann Intensive Care 2013; 3: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schädler D, Pausch C, Heise D, et al. The effect of a novel extracorporeal cytokine hemoadsorption device on IL-6 elimination in septic patients: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0187015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hetz H, Berger R, Recknagel P, et al. Septic shock secondary to β-hemolytic streptococcus-induced necrotizing fasciitis treated with a novel cytokine adsorption therapy. Int J Artif Organs 2014; 37: 422–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Träger K, Skrabal C, Fischer G, et al. Hemoadsorption treatment of patients with acute infective endocarditis during surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass – a case series. Int J Artif Organs 2017; 40: 240–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]