Abstract

This study evaluated the effects of ketamine-dexmedetomidine-midazolam as part of an opioid-free, multimodal protocol in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. In a prospective, blinded, randomized clinical trial, cats received either 1 of 2 doses of ketamine [5 mg/kg body weight (BW), n = 10, K5 or 7 mg/kg BW, n = 13, K7] with midazolam (0.25 mg/kg BW) and dexmedetomidine (40 μg/kg BW) intramuscularly, intraperitoneal bupivacaine (2 mg/kg BW) and subcutaneous meloxicam (0.2 mg/kg BW) after surgery. Buprenorphine (0.02 mg/kg BW, intravenously) was administered if pain scores exceeded intervention scores with 2 pain scoring systems. Similar prevalence of rescue analgesia was observed (K5 = 6/10; K7 = 7/13) with significantly lower requirements in kittens (2/8) than adults (11/15). Tachypnea (K5 = 7/10 and K7 = 9/13) and desaturation (K5 = 3/10 and K7 = 4/13) were the 2 most common complications. Age influenced the prevalence of rescue analgesia. Most adult cats required opioids for postoperative pain relief.

Résumé

Effets anesthésiants et analgésiques d’un protocole injectable sans opioïde chez des chats soumis à une ovario-hystérectomie : essai clinique prospectif, randomisé, à l’aveugle. Lors de la présente étude nous avons évalué les effets de la combinaison kétamine-dexmedetomidine-midazolam comme élément d’un protocole multimodal sans opioïde chez des chats soumis à une ovario-hystérectomie. Dans un essai clinique prospectif, randomisé, à l’aveugle, des chats reçurent une des deux doses de kétamine [5 mg/kg poids corporel (BW), n = 10, K5 ou 7 mg/kg BW, n = 13, K7] avec du midazolam (0,25 mg/kg BW) et du dexmedetomidine (40 μg/kg BW) par voie intramusculaire, de la bupivacaine par voie intrapéritonéale (2 mg/kg BW) et du meloxicam sous-cutané (0,2 mg/kg BW) après la chirurgie. De la buprenorphine (0,02 mg/kg BW, par voie intraveineuse) fut administrée si les pointages de douleur excédaient les pointages d’intervention avec deux systèmes de pointage de la douleur. Une prévalence similaire d’analgésie de secours fut observée (K5 = 6/10; K7 = 7/13) avec des demandes significativement moindres chez les chatons (2/8) que chez les adultes (11/15). De la tachypnée (K5 = 7/10 et K7 = 9/13) et de la désaturation (K5 = 3/10 et K7 = 4/13) étaient les deux complications les plus fréquentes. L’âge influençait la prévalence de l’analgésie de secours. La plupart des chats adultes ont requis des opioïdes pour soulager la douleur post-opératoire.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Introduction

The international veterinary community does not always have access to drugs for basic standard of care including anesthetics and analgesics (1). Surgical and anesthetic procedures are often performed with injectable anesthetics with limited or no perioperative analgesia (2). Drugs such as opioids and volatile anesthetics are not readily available in many countries, although opioids are one of the cornerstones of acute pain management (3). Unfortunately, frequent drug shortage is now also a reality in North America. This problem potentially leads to unnecessary animal suffering and is a welfare issue. Colloquially, there has been an increase in continuing education and “blogs” regarding alternatives to opioid analgesia in veterinary patients (4,5). However, studies on “opioid-free anesthesia” and alternatives to volatile anesthesia are rare in veterinary medicine (6,7).

The objective of this study was to compare the anesthetic and analgesic effects of an opioid-free, low-volume, injectable anesthetic protocol using a combination of 1 of 2 doses of ketamine [5 mg/kg body weight (BW) or 7 mg/kg BW] with dexmedetomidine and midazolam in a multimodal analgesic protocol. The authors hypothesized that both doses of ketamine would provide an appropriate depth of anesthesia, effective analgesia (i.e., low prevalence of rescue analgesia), and minimal anesthetic complications in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was approved by the animal care committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (FMV), Université de Montréal (18-RECH-1978). The study was performed between November 2018 and January 2019 and is reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT guidelines; http://www.consort-statement.org).

Animals

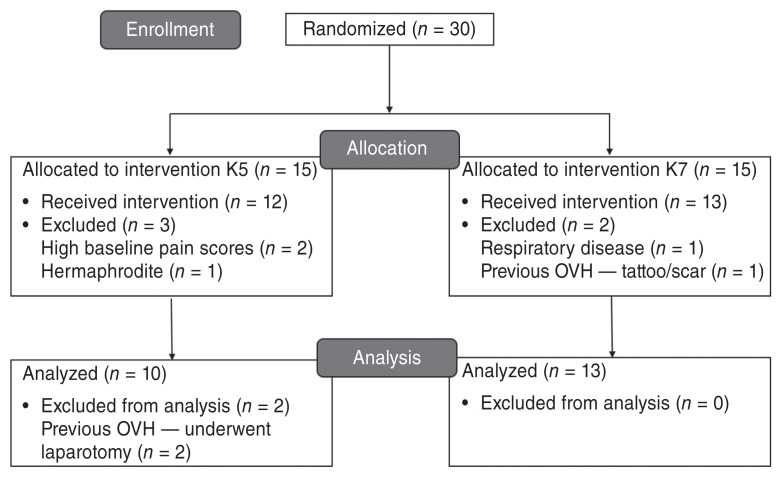

Thirty female cats previously from shelter facilities were enrolled in a prospective, blinded, randomized clinical trial after obtaining the adoptive owners’ written consent (Figure 1). Inclusion criteria included any healthy cat of any breed and older than 4 mo of age. Cats were deemed healthy based on medical history, physical examination, hematocrit, and serum total protein. Pregnant and lactating cats were also eligible for inclusion since they represent the normal population undergoing ovariohysterectomy in sterilization programs. Exclusion criteria included body weight less than 1 kg, cardiac arrhythmias, body condition score > 7 or < 3 on a scale from 1 to 9, anemia (hematocrit < 25%), hypoproteinemia (total protein < 59 g/L), shy or fearful individuals not allowing adequate pain assessment, baseline pain scores consistent with presence of pain, evidence of previous ovariohysterectomy (i.e., visualization of scar and/or tattoo), and clinical signs of systemic disease. The cats were admitted to the FMV at least 12 h before general anesthesia and were housed individually in adjacent cages in a cat ward. Each cat had access to water and food bowls and a litter box. Environmental enrichment included a hanging toy, blankets, and a box in which the cat could hide or use as an elevated surface. Food, but not water was withheld for 8 to 12 h before general anesthesia.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram to demonstrate study randomization, group allocation and data analysis. Cats received a combination of ketamine (K5 group = 5 mg/kg BW of ketamine; K7 group = 7 mg/kg BW of ketamine), midazolam, and dexmedetomidine by the intramuscular route of administration and underwent ovariohysterectomy (OVH).

Experimental design and treatment groups

Thirty subjects were randomized into 1 block with allocation ratio of 1:1. Randomization was performed by a researcher (ME) not involved with pain assessment using a randomization plan generator (www.randomization.com). Upon arrival, each cat was sequentially assigned a number (1 to 30) and according to this number, was allocated to 1 of 2 treatment groups: K5 (5 mg/kg BW of ketamine) or K7 (7 mg/kg BW of ketamine). The cats received a combination of ketamine (K5 or K7; Ketaset, Zoetis, Kirkland, Quebec), dexmedetomidine (Dexdomitor; Zoetis), 40 μg/kg BW, and midazolam (Midazolam; Sandoz, Boucherville, Quebec), 0.25 mg/kg BW, administered together into the lumbar epaxial muscles (IM) through a 1-mL syringe. The same 2 observers (TD, HR) performed the intramuscular injections and were masked to treatment.

Once lateral recumbency was achieved, a 22-gauge catheter was inserted into the cephalic vein using aseptic technique. The cat was placed in sternal recumbency and the tongue of the cat was pulled slightly rostral for intubation with a supraglottic airway device (v-gel; Docsinnovent, London, UK). Proper positioning of the supraglottic airway device was confirmed with capnography and cats were allowed to spontaneously breathe room air. The cats were then placed in dorsal recumbency on a circulating warm water vinyl blanket; the surgical site was clipped and prepared using aseptic technique.

Anesthesia was performed by the same veterinarian (ME). Physiologic parameters were measured using a multi-parametric monitor (LifeWindow 6000V veterinary multiparameter monitor; Digicare Animal Health, Boynton Beach, Florida, USA), which included electrocardiogram, capnography, pulse oximetry, and arterial blood pressure (oscillometric technique). Arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation (SpO2), end-tidal CO2 (PETCO2), respiratory rate (fR), heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP) were recorded every 5 min throughout the anesthetic period. Rectal temperature (T) was recorded once immediately after the end of anesthesia. Lactated Ringer’s solution (Lactated Ringer’s Inj. Bag/500 mL; McCarthy & Sons Service, Calgary, Alberta) was administered intravenously at 10 mL/kg BW per hour throughout. Ovariohysterectomy was performed by an experienced veterinarian (BM) using a ventral midline incision and the feline pedicle tie technique, described elsewhere (8). Immediately following laparotomy and before ovariohysterectomy, bupivacaine HCl 0.25% USP (Sensorcaine; AstraZeneca, Mississauga, Ontario), 2 mg/kg BW, was administered intraperitoneally. The solution was equally divided into 3 parts. Each third of the solution was instilled over the left and right ovarian pedicles and the caudal aspect of the uterus. The surgery was continued approximately 1 min after the intraperitoneal administration of bupivacaine, as previously described (9). At the end of the surgical procedure, a 2-cm green line tattoo was applied lateral to the ventral midline incision for visual identification of a neutered animal.

A ketamine bolus (0.5 mg/kg BW) was administered intravenously if there were signs of an inadequate depth of anesthesia. These signs included swallowing reflex, purposeful movement or increases in MAP of ≥ 15% compared with pre-surgical values. Boluses were administered at a minimum interval of 1 min between doses. Mean arterial blood pressure was measured 1 min after administering each bolus.

Atipamezole (Antisedan 5.0 mg/mL; Zoetis), 400 μg/kg BW, IM, was administered at the end of surgery followed by meloxicam (Metacam 0.5%; Boehringer Ingelheim, Burlington, Ontario), 0.2 mg/kg BW, SC. Extubation was performed when palpebral reflexes returned. A second dose of meloxicam (Metacam 0.5 mg/mL oral suspension; Boehringer Ingelheim), 0.05 mg/kg BW, PO was administered 24 h after the first dose.

Onset of anesthesia was defined as the time from the end of IM injection with ketamine-dexmedetomidine-midazolam (KET-DEX-MID) until lateral recumbency and was measured with a chronometer. Duration of surgery (time from first incision to placement of the last suture) and of anesthesia (time from IM injection to atipamezole injection) and time to sternal recumbency (time from atipamezole injection to first sternal recumbency) were recorded for each cat.

Complications

Anesthetic complications were defined as any observation of the following: tachycardia (HR > 160 bpm), bradycardia (HR < 70 bpm), hypotension (MAP < 50 mmHg), bradypnea (fR < 4 rpm), tachypnea (fR > 30 rpm), hypercapnia (PETCO2 > 50 mmHg), desaturation (SpO2 < 90%), and hypothermia (T < 36.0°C). Light depth of anesthesia was treated with a bolus of ketamine as previously described. Assisted ventilation with intermittent positive pressure was instituted by connecting an Ambu-bag (Portex 1st Response Adult Manual Resuscitators; Smith Medical, Markham, Ontario) to the supraglottic airway device and giving 12 breaths/min using room air for 3 min in cases of hypercapnia or desaturation. If the latter was not effective, the Ambu-bag was disconnected, and a Mapleson D circuit (Moduflex Bain Circuit Adaptor; DISPOMED, Joliette, Quebec) was attached to the supraglottic airway device with the administration of 100% oxygen. Additional external heat sources (e.g., forced warm air blanket) were used for the treatment of hypothermia.

Pain and sedation scores

Pain assessment was performed approximately 1 h before the administration of injectable anesthetics (time 0, baseline) and at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h after the end of surgery by the same observer (TD) blinded to the treatment group. Two pain-scoring systems, the Glasgow feline composite measure pain scale (CMPS-Feline) (10) and the Feline Grimace Scale (FGS) (11), were used for pain assessment. The CMPS-Feline consists of 7 questions regarding vocalization, posture, attention to the wound, 2 facial expression features, interaction with the observer, response to palpation, and overall demeanor, adding up to a maximum score of 20 points (10). The FGS is a facial expression-based scoring system that consists of 5 action units (ear position, orbital tightening, muzzle tension, whiskers change, and head position), each one receiving a score of 0 to 2 adding up to a maximum score of 10 points (11). Because not all action units can be visualized in all cats at all time points, the final score of the FGS was recorded as a fraction (i.e., total score divided by the maximum score based on the number of the action units included in the evaluation).

Sedation was evaluated by the same individual (TD) using a Dynamic Interactive Visual Analog Scale (DIVAS) at times 0 (baseline), 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h after the end of surgery and before pain assessment. The DIVAS was determined as previously described (9). The DIVAS score was derived from a 10 cm bar where 0 corresponded to “no sedation” and 10 corresponded to the “maximum sedation possible.”

Rescue analgesia

Rescue analgesia using buprenorphine (Vetergesic; Champion Alstoe, Whitby, Ontario), 0.02 mg/kg BW, IV, was administered when pain scores were ≥ 5/20 (CMPS-Feline) and ≥ 0.39/1.0 (FGS). To avoid bias, data collected after the administration of rescue analgesia were not included in the statistical analysis. However, pain evaluations for all cats were continued until the end of the study.

Statistical methods

This was an exploratory study and sample size calculations were not performed beforehand. Statistical analysis was performed with standard software (SAS, version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Normality was visually assessed, and the distribution of residual values was considered symmetrical. Demographic data between treatment groups were analyzed using equal variances t-tests. Pain and sedation scores were analyzed using linear mixed models with group and time as the fixed factors, cats nested within the treatment group as random factor and age group (kittens or adults) as a co-factor. Pairs of means were compared using priori contrasts and the alpha level for each comparison was adjusted with the sequential Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Scores of CMPS-Feline were recorded as the total score. Scores of FGS were recorded as percentage because one or more action units could perhaps not be visible during pain assessment due to the cat’s position and/or in the presence of residual anesthetic effects. The number of cats receiving rescue analgesia and the frequency of complications were analyzed using the exact X2 test. The relationship between pain scores from the CMPS-Feline and FGS was analyzed using a linear mixed model with cat as a random factor and the CMPS-Feline scores as the fixed factor. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Twenty-three cats were included in this study (Figure 1). Because age was not precise for most cats, they were categorized into 2 age groups: kitten or adult. Kittens were defined as cats between 4 and 6 mo of age. Adults were defined as cats over 6 mo of age as confirmed by dentition and the presence of all permanent teeth (12). Body weight, age group, hematocrit, total protein, onset of anesthesia, duration of surgery, anesthesia and time to sternal recumbency were not different between treatment groups (Table 1). None of the cats required a ketamine bolus.

Table 1.

Body weight, age group, hematocrit, total protein, onset of anesthesia, duration of surgery and anesthesia and time to sternal recumbency in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy after the administration of a combination of ketamine (5 or 7 mg/kg BW; groups K5 and K7, respectively) with dexmedetomidine (40 μg/kg BW) and midazolam (0.25 mg/kg BW) by the intramuscular route. Data are reported as mean ± SD.

| K5 (n = 10) | K7 (n = 13) | P-valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 0.7 | 0.36 |

| Age group (number) | |||

| Kitten | 3 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Adult | 7 | 8 | |

| Hematocrit (%) | 38.5 ± 6.8 | 37.7 ± 3.4 | 0.71 |

| Total protein (g/L) | 62 ± 4 | 62 ± 7 | 0.92 |

| Onset of anesthesia (min) | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 0.93 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 15.5 ± 1.7 | 15.8 ± 1.0 | 0.64 |

| Duration of anesthesia (min) | 31.4 ± 3.8 | 30.5 ± 2.5 | 0.52 |

| Time to sternal recumbency (min) | 16.4 ± 9.0 | 16.8 ± 8.8 | 0.92 |

The P-value refers to the comparison between groups.

The prevalence of anesthetic complications was not significantly different between treatment groups. Tachycardia was observed in 1 cat in K5 and none of the cats in K7 (P = 0.44). Tachypnea was observed in 7 cats in K5 and 9 cats in K7 (P = 1). Desaturation was observed in 3 cats in K5 and 4 cats in K7 (P = 1). Bradycardia, hypotension, bradypnea, hypercapnia and hypothermia were not observed in any cat. All cats were discharged from hospital at least 24 h after surgery without postoperative complication.

CMPS-Feline/FGS pain scores

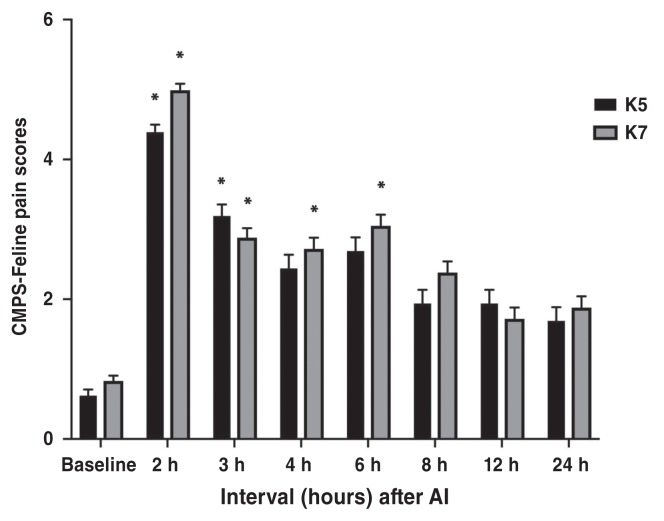

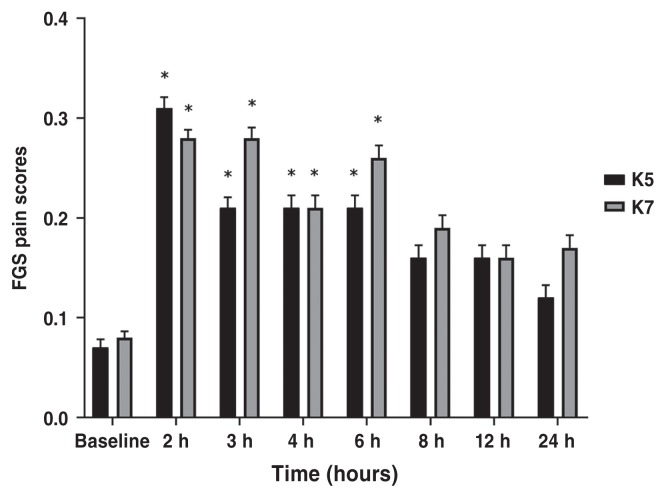

Pain scores at 0.5 h and 1 h time points were discarded because of purposeless movements and restlessness during anesthetic recovery which did not allow appropriate pain assessment. There was no significant difference between treatment groups at any time points according to CMPS-Feline and FGS (P > 0.38 and P > 0.25, respectively). CMPS-Feline pain scores were significantly higher at 2 h (P < 0.0001) and 3 h (P = 0.0004) in K5 group; and at 2 h (P < 0.0001), 3 h (P = 0.0004), 4 h (P = 0.001), and 6 h (P = 0.0001) in K7 group, compared with baseline values (Figure 2; Table 2). Feline grimace scale pain scores were significantly higher at 2 h (P < 0.0001), 3 h (P = 0.0025), 4 h (P = 0.0025), and 6 h (P = 0.0025) in K5 group; and at 2 h (P < 0.0001), 3 h (P = 0.0004), 4 h (P = 0.001), and 6 h (P < 0.0001) in K7 group, compared with baseline values (Figure 3; Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM scores for the Glasgow feline composite measure pain scale (CMPS-Feline) in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy.

* Indicates significant difference when compared with baseline values. K5 group = 5 mg/kg BW of ketamine, K7 group = 7 mg/kg BW of ketamine.

Table 2.

Least square means of pain scores in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy using the Glasgow feline composite measure pain scale (CMPS-Feline) and the Feline Grimace Scale (FGS). Anesthetic protocol comprised a combination of ketamine (5 or 7 mg/kg BW; groups K5 and K7, respectively) with dexmedetomidine (40 μg/kg BW) and midazolam (0.25 mg/kg BW) by the intramuscular route. Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval).

| Postoperative values | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Pain scoring | Group | Baseline (0) | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 6 h | 8 h | 12 h | 24 h |

| CMPS-Feline | K5 | 0.62 (−0.25 to 1.49) | 4.39 (3.35 to 5.43)* | 3.19 (1.95 to 4.42)* | 2.44 (1.20 to 3.67) | 2.69 (1.45 to 3.92) | 1.94 (0.70 to 3.17) | 1.94 (0.70 to 3.17) | 1.69 (0.45 to 2.92) |

| K7 | 0.83 (0.1 to 1.56) | 4.99 (4.10 to 5.89)* | 2.88 (1.87 to 3.90)* | 2.72 (1.70 to 3.73)* | 3.05 (2.03 to 4.07)* | 2.38 (1.37 to 3.40) | 1.72 (0.70 to 2.73) | 1.88 (0.87 to 2.90) | |

| FGS | K5 | 0.07 (0.0 to 0.14) | 0.31 (0.23 to 0.39)* | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.30)* | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.30)* | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.30)* | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.25) | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.25) | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.22) |

| K7 | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.14) | 0.28 (0.20 to 0.36)* | 0.28 (0.20 to 0.36)* | 0.21 (0.13 to 0.28)* | 0.26 (0.18 to 0.33)* | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.26) | 0.16 (0.08 to 0.23) | 0.17 (0.10 to 0.25) | |

Indicates significant difference when compared with baseline.

Figure 3.

Mean ± SEM scores for the feline grimace scale (FGS) in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy.

* Indicates significant difference when compared with baseline values. K5 group = 5 mg/kg of ketamine, K7 group = 7 mg/kg of ketamine.

Rescue analgesia

Thirteen cats required rescue analgesia; 6 cats in K5 and 7 cats in K7. Prevalence of rescue analgesia was not significantly different between treatment groups (P = 1). According to age groups, 2 cats in the kitten group and 11 cats in the adult group required rescue analgesia (25.0% and 73.3%, respectively,). The prevalence of rescue analgesia was significantly greater in adults than in kittens (P = 0.039). Time points at which rescue analgesia was administered were 2 h (n = 9) and 3 h (n = 4).

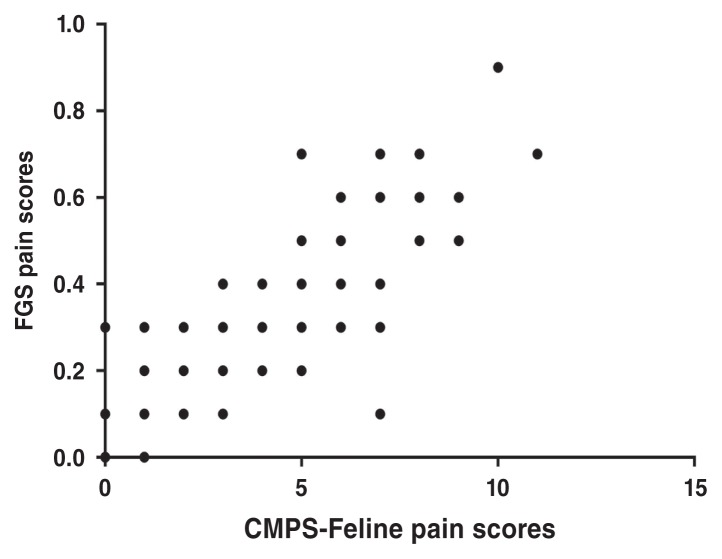

Relationship between CMPS-Feline and FGS

Data from all time points, except for times 0.5 and 1 h, including data after rescue analgesia, were included in the analysis of the relationship between both pain scales. There was a positive and significant association between CMPS-Feline and FGS scores (P < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Relationship between the Glasgow feline composite measure pain scale (CMPS-Feline) and the feline grimace scale (FGS) in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy receiving an injectable anesthetic protocol. The linear mixed model indicated a positive and significant association between the CMPS-Feline and FGS pain scores (P < 0.0001).

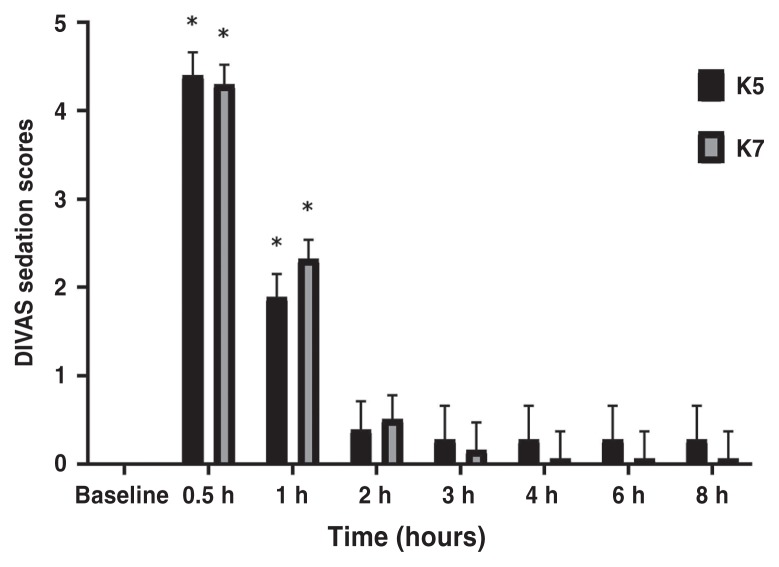

Sedation scores

There was no significant difference between treatment groups at any time points according to the DIVAS (P > 0.21). When compared with baseline values, sedation scores were increased in K5 and K7 at 0.5 h (P < 0.0001 for both) and 1 h (P < 0.0001 for both) (Table 3, Figure 5). There was no effect of age (P = 0.13) but the interaction between treatment group and age group was significant (P = 0.0025). Kittens had overall lower sedation scores than adults in K5 (P = 0.0044) but not in K7 (P = 0.14). This difference was not significant after adjustment, but it could be an indication of the direction of the sedation effect between age and treatment.

Table 3.

Least square means of sedation scores in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Anesthetic protocol comprised a combination of ketamine (5 or 7 mg/kg BW; K5 and K7 group, respectively) with dexmedetomidine (40 μg/kg BW) and midazolam (0.25 mg/kg BW) by the intramuscular route. Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval).

| Group | 0 h | 0.5 h | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 h | 6 h | 8 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIVAS | ||||||||

| K5 | −0.16 (−0.61 to 0.29) | 4.40 (3.89 to 4.92)* | 1.89 (1.38 to 2.41)* | 0.39 (−0.24 to 1.03) | 0.28 (−0.49 to 1.05) | 0.28 (−0.49 to 1.05) | 0.28 (−0.49 to 1.05) | 0.28 (−0.49 to 1.05) |

| K7 | 0.04 (−0.36 to 0.43) | 4.30 (3.86 to 4.74)* | 2.32 1.88 to 2.76)* | 0.51 (−0.04 to 1.06) | 0.16 (−0.47 to 0.79) | 0.06 (−0.57 to 0.69) | 0.06 (−0.57 to 0.69) | 0.06 (−0.57 to 0.69) |

Indicates significant difference when compared with baseline.

DIVAS — Dynamic interactive visual analog scale.

Figure 5.

Mean ± SEM scores for the dynamic interactive visual analog scale (DIVAS) in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. There were no significant differences between the treatment groups at any time point.

* Indicates significant difference when compared with baseline values. K5 group = 5 mg/kg BW of ketamine, K7 group = 7 mg/kg BW of ketamine.

Discussion

In this randomized clinical study, an opioid-free, low-volume injectable protocol using KET-DEX-MID provided rapid immobilization, unconsciousness and smooth induction of anesthesia in cats. The duration and depth of anesthesia were adequate for all surgical interventions after single administration with rapid antagonism by atipamezole; no additional boluses of ketamine were required. These anesthetic effects are in accordance with the Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ 2016 Veterinary Medical Care Guidelines for spay-neuter programs (13). It provides a significant advantage over the QUAD protocol (ketamine, methadone, medetomidine, and midazolam) since the latter requires volatile anesthesia after administration to induce surgical depth of anesthesia (14). However, the study showed that most adult cats require the administration of an opioid for the treatment of pain after surgery even if other analgesic drugs were administered. Though not an intended comparison, the protocol appears to provide better postoperative analgesia and fewer sedative effects in kittens. Importantly, nearly a third of all animals required oxygen supplementation or assisted ventilation due to arterial oxyhemoglobin desaturation. Therefore, this combination might not be a good option in situations in which supplemental analgesia and oxygen are not available.

The combination of KET-DEX-MID proved an effective and rapid combination for anesthesia in cats. The increased dose of ketamine (7 mg/kg BW versus 5 mg/kg BW) did not affect the speed of onset, duration, nor the time to recovery in this study. The combination induced lateral recumbency and general anesthesia within 2 to 3 min following IM administration. The duration of anesthesia was approximately 32 min in both treatment groups. This was sufficient to perform ovariohysterectomy in all cats without the need for ketamine boluses due to inadequate depth of anesthesia. The true duration of anesthesia was not evaluated and could be much longer since atipamezole was administered to antagonize the effects of dexmedetomidine and hasten anesthetic recovery at the end of each procedure. Time to sternal recumbency was on average 16 min, with no differences between groups. These results are in agreement with previous studies using ketamine-based injectable protocols for which minimal cardiovascular effects, excellent muscle relaxation, and smooth recoveries were observed (15–17). For use in sterilization programs, the combination KET-DEX-MID administered IM is an efficient and appropriate choice for anesthesia. When used for short procedures, the lower dose of ketamine (5 mg/kg BW) is a prudent choice. Further investigation with varied dosing of all 3 drugs is warranted to further refine the protocol.

Analgesia provided by the combination of KET-DEX-MID, intraperitoneal bupivacaine, and meloxicam in this study was inadequate. The prevalence of rescue analgesia was 6/10 in K5 and 7/13 in K7. In previous studies, the intraperitoneal administration of bupivacaine in combination with buprenorphine with or without meloxicam provided superior analgesia in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy than in the current study, with prevalence of rescue analgesia between 0% and 27% (9,18). Interestingly, kittens in this study had a significantly lower prevalence of rescue analgesia than adults (2/8 versus 11/15, respectively). This result is in agreement with a previous study in which kittens (< 4 mo of age) showed fewer behavioral signs of pain than adults (19) even if kittens could express pain behaviors differently than adults. It is not clear if better analgesia was observed in kittens than adults due to physiological differences, changes in pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of anesthetics and analgesics used in the study, if there is less tissue damage and trauma during surgery in kittens than adults, if there are behavioral differences between the 2 age groups confounding pain assessment, or all the above. For example, it is now known that aging impacts thermal antinociception of hydromorphone in cats and the drug requires more frequent dosing in kittens (< 6 mo of age) compared with adults, and similar differences with aging could occur with other anesthetics (20).

In the current study, the CPMS-Feline and FGS were consistently elevated at postoperative timepoints in both groups. It is not surprising since pain scores are expected to increase after tissue trauma and inflammation produced by surgery. There was a positive and statistically significant relationship between the 2 scales, supporting their use as pain assessment instruments in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy using an injectable anesthetic protocol. A positive significant correlation (rho = 0.86, P < 0.001) was also observed between these 2 scoring systems in conscious pain-free cats and those with naturally occurring pain from different sources and intensities (11). This study shows the importance of postoperative pain assessments in all cats even in a high-volume sterilization program, as the authors expected this combination to provide better analgesia than observed. Had these assumptions been used in a high-volume scenario, without postoperative pain evaluations, many cats would have been left in pain despite receiving a presumed “effective” technique. Further research is merited to compare similar anesthetic protocols using opioid versus opioid-free techniques. Additionally, it is possible that the administration of meloxicam before surgery instead of after surgery could have had an impact on postoperative pain and this should be further investigated.

Residual anesthetic effects may increase sedation scores with a potential impact in postoperative pain assessment (9,18,21). Pain assessment was difficult also due to the ketamine-induced purposeless movement and restlessness in some cats especially after the administration of atipamezole to antagonize the effects (e.g., muscle relaxation) of dexmedetomidine. Ketamine-based protocols are known to confound the application of pain scales in cats (22). This information has not been validated for the FGS. Based on these observations, the possible confounding effects of ketamine in pain assessment, and the significant difference of sedation scores between baseline values and 0.5 h and 1 h for both treatment groups, data from pain scores before 2 h were not included in the analysis. This was a potential limitation of the study and there is still a need for pain scoring systems that are reliable even in the presence of residual ketamine-based anesthetic protocols. Additionally, there was an interaction between treatment and age groups. In K5, kittens had overall lower sedation scores than adults. Although this difference was no longer significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons, it could be of clinical interest if rapid recovery from anesthesia with minimal sedation is desired. It could represent another advantage of using a lower dose of ketamine (i.e., K5) in cats.

Some anesthetic complications were observed in both groups using KET-DEX-MID. The 2 most common complications according to our definitions, in order, were tachypnea (7/10 in K5 and 9/13 in K7) and desaturation of peripheral arterial oxyhemoglobin (< 90%; 30% in K5 and 30.8% in K7). Desaturation has been observed in previous studies using ketamine (5 mg/kg BW) and dexmedetomidine (25 μg/kg BW) in which mean SpO2 was 90% [interquartile range (IQR): 84 to 92%] but not with ketamine (5 mg/kg BW), dexmedetomidine (15 μg/kg BW), and hydromorphone (0.05 mg/kg BW) (23,24). Neither of these studies reported tachypnea. Although, in the former study using ketamine at 5 mg/kg BW and dexmedetomidine at 25 μg/kg BW, the mean respiratory rate was 33 ± 13 bpm, which is above our study’s definition of tachypnea (> 30 bpm). The principle of pulse oximetry states that desaturation (< 90%) indicates hypoxemia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg) which can induce tachypnea. It is therefore possible that hypoxemia was occurring in these patients. However, the impact of peripheral vasoconstriction produced by dexmedetomidine may have caused decreased readings of peripherally measured SpO2 (23,25). Our results could be an overinterpretation of oxyhemoglobin desaturation. The physiological impact of hypoxemia, however, is important and appropriate monitoring with the ability to provide assisted ventilation and supplemental oxygen is recommended for these protocols. Simultaneous arterial blood gas analysis would allow better interpretation of these complications and could be a subject of future studies.

In addition to some of the limitations presented, this study used a small sample size, which increases the likelihood of type II error. The lack of an opioid-based or a different anesthetic injectable protocol for comparison is also another limitation. Additionally, dexmedetomidine was considered a part of the analgesic protocol, but its effects were antagonized by atipamezole to facilitate recovery. It is not known if analgesic effects would have been better at a cost of prolonged anesthetic recoveries with other possible complications (e.g., regurgitation and aspiration pneumonia) if atipamezole had not been administered. The literature, however, supports the use of atipamezole with agonists of α2-adrenoceptors without compromising postoperative analgesia in cats after ovariohysterectomy (15,16). Finally, the study did not investigate the quality of anesthetic recovery due to the lack of appropriate scoring systems for this purpose. It would be interesting to know if the quality of anesthetic recovery is better with comparable injectable protocols with or without opioids, or with the use of inhalant anesthesia.

In conclusion, the combination of an opioid-free, low volume, injectable anesthetic protocol using KET-DEX-MID provides rapid immobilization and unconsciousness, and appropriate depth and duration of anesthesia in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Appropriate physiologic monitoring and interventions, particularly for respiratory complications, is recommended. Despite the use of intraperitoneal bupivacaine and postoperative meloxicam, the protocol did not provide adequate analgesia for all individuals with most cats requiring rescue analgesia. However, the protocol could be a suitable option for kittens (4 to 6 mo old), since it provided better analgesia and reduced sedative effects (K5 only) than it did for adults. Based on our results, the use of opioid-based analgesia is required for most adult cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy even when other analgesic drugs are being administered.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Truc Diep received a Canada-ASEAN scholarship and Educational Exchanges for Development (SEED). This study was awarded with the Zoetis Investment in Innovation Fund. Dr. Paulo Steagall’s laboratory is funded by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada. The authors thank Guy Beauchamp for the statistical analysis. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.WSAVA Global Pain Council. Global Pain Survey, 2013. [Last accessed November 10, 2019]. Available from: https://www.wsava.org/WSAVA/media/PDF_old/GPC-Survey-Results_July_2013.pdf.

- 2.Pestean C, Oana L, Bel L, Scurtu I, Clinciu G, Ober C. A Survey of Canine Anaesthesia in Veterinary Practice in Cluj-Napoca. Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca Veterinary Medicine. 2016;73:325–328. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon BT, Steagall PV. The present and future of opioid analgesics in small animal practice. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2017;40:315–326. doi: 10.1111/jvp.12377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Looney A. Alternatives to opioids in veterinary patients. 2017. [Last accessed April 6, 2020]. Available from: http://blog.vetbloom.com/anesthesia-analgesia/alternatives-toopioids-in-veterinary-patients/

- 5.Looney A. Opioid minimal anesthesia. 2017. [Last accessed April 6, 2020]. Available from: https://vetbloom.com/product?catalog=opioid-minimal-anesthesia.

- 6.Geddes AT, Stathopoulou T, Viscasillas J, Lafuente P. Opioid-free anaesthesia (OFA) in a springer spaniel sustaining a lateral humeral condylar fracture undergoing surgical repair. Vet Rec Case Rep. 2019;7:e000681. [Google Scholar]

- 7.White DM, Mair AR, Martinez-Taboada F. Opioid-free anaesthesia in three dogs. Open Vet J. 2017;7:104–110. doi: 10.4314/ovj.v7i2.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller KP, Rekers W, Ellis K, Ellingsen K, Milovancev M. Pedicle ties provide a rapid and safe method for feline ovariohysterectomy. J Feline Med Surg. 2016;18:160–164. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15576589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benito J, Monteiro B, Lavoie AM, Beauchamp G, Lascelles BDX, Steagall PV. Analgesic efficacy of intraperitoneal administration of bupivacaine in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2016;18:906–912. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15610162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid J, Scott EM, Calvo G, Nolan AM. Definitive Glasgow acute pain scale for cats: Validation and intervention level. Vet Rec. 2017;180:449. doi: 10.1136/vr.104208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evangelista M, Watanabe R, Leung VSY, Monteiro BM, O’Toole E, Pang DSJ, Steagall PV. Facial expressions of pain in cats: The development and validation of a Feline Grimace Scale. Sci Rep. 2019;9:19128. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55693-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tutt C. Small Animal Dentistry: A Manual of Techniques. 1st ed. Ames, Iowa: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffin B, Bushby PA, McCobb E, et al. The Association of Shelter Veterinarians’ 2016 Veterinary Medical Care Guidelines for Spay-Neuter Programs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2016;249:165–188. doi: 10.2460/javma.249.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Yates D, Hunt J, Murrell J. Comparison between methadone and buprenorphine within the QUAD protocol for perioperative analgesia in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21:723–731. doi: 10.1177/1098612X18798840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruniges N, Taylor PM, Yates D. Injectable anaesthesia for adult cat and kitten castration: Effects of medetomidine, dexmedetomidine and atipamezole on recovery. J Feline Med Surg. 2016;18:860–867. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15598550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polson S, Taylor PM, Yates D. Analgesia after feline ovariohysterectomy under midazolam-medetomidine-ketamine anaesthesia with buprenorphine or butorphanol, and carprofen or meloxicam: A prospective, randomised clinical trial. J Feline Med Surg. 2012;14:553–559. doi: 10.1177/1098612X12444743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ueoka N, Hikasa Y. Antagonistic effects of atipamezole, flumazenil and 4-aminopyridine against anaesthesia with medetomidine, midazolam and ketamine combination in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2008;10:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benito J, Monteiro B, Beaudry F, Steagall P. Efficacy and pharmacokinetics of bupivacaine with epinephrine or dexmedetomidine after intraperitoneal administration in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy. Can J Vet Res. 2018;82:124–130. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polson S, Taylor PM, Yates D. Effects of age and reproductive status on postoperative pain after routine ovariohysterectomy in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2013;16:170–176. doi: 10.1177/1098612X13503651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon BT, Scallan EM, Monteiro BP, Steagall PVM. The effects of aging on hydromorphone-induced thermal antinociception in healthy female cats. Pain Rep. 2019;4:e722. doi: 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steagall PV, Benito J, Monteiro BP, Doodnaught GM, Beauchamp G, Evangelista MC. Analgesic effects of gabapentin and buprenorphine in cats undergoing ovariohysterectomy using two pain-scoring systems: A randomized clinical trial. J Feline Med Surg. 2018;20:741–748. doi: 10.1177/1098612X17730173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buisman M, Wagner MC, Hasiuk MM, Prebble M, Law L, Pang DS. Effects of ketamine and alfaxalone on application of a feline pain assessment scale. J Feline Med Surg. 2016;18:643–651. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15591590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armstrong T, Wagner MC, Cheema J, Pang DS. Assessing analgesia equivalence and appetite following alfaxalone- or ketamine-based injectable anesthesia for feline castration as an example of enhanced recovery after surgery. J Feline Med Surg. 2018;20:73–82. doi: 10.1177/1098612X17693517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasiuk MMM, Brown D, Cooney C, Gunn M, Pang DS. Application of fast-track surgery principles to evaluate effects of atipamezole on recovery and analgesia following ovariohysterectomy in cats anesthetized with dexmedetomidine-ketamine-hydromorphone. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2015;246:645–653. doi: 10.2460/javma.246.6.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Severinghaus JW, Spellman MJ., Jr Pulse oximeter failure thresholds in hypotension and vasoconstriction. Anesthesiology. 1990;73:532–537. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199009000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]