Abstract

Background

Worldwide, hypothyroidism affects 3.7% of the population, and is associated with impaired quality of life. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of cognitive- behavioral therapy (CBT) on the quality of life in women with hypothyroidism.

Methods

96 women with hypothyroidism randomly allocated into two groups: CBT group (n = 48) and control group (n = 48). Women in the CBT group were classified into four sub-groups of 12, and each sub-group received eight sessions of counseling (each session lasting 90 min). We collected data using a demographic questionnaire and the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF 36) for measuring the quality of life. We used the independent t-test, chi-square test and ANCOVA to analyze the data.

Results

Five women from each group withdrew from the study, leaving 43 women in each group. The scores on physical functioning, physical health problems, social functioning and pain improved in the CBT group after the intervention, but the differences between the two groups were not significant. The scores on emotional health, emotional health problems, energy and emotions, and general health were significantly better in the CBT group than those in the control group (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Counseling using CBT can improve some aspects of quality of life, including emotional health, emotional health problems, energy and general health in patients with hypothyroidism.

Trial registration number

Iranian Registry for Clinical Trials: 20190323043101 N1. https://www.irct.ir/

Keywords: Cognitive behavioral therapy, Hypothyroidism, Quality of life

Background

Hypothyroidism defined as the insufficient amount of thyroid hormones, that may result from disorders of the thyroid gland, pituitary gland or hypothalamus [1]. It is estimated it affects 3.7% of the population worldwide [2]. A cohort study (2006–2011) in Iran showed that the prevalence of hypothyroidism was 3.3 and 2.1 per 1000 (person-year) in adult women and men, respectively [3]. The Iranian government started to fortify the salt with iodine from 1990, and at the present time more than 95% of Iranian households use iodized salt, therefore, the risk of the goitre due to iodine insufficiency has decreased significantly [4].

The most commonly used treatment for hypothyroidism is levothyroxine. A study showed that women, who were diagnosed with hypothyroidism and underwent treatment with levothyroxine, showed improvement in the overall quality of life after six months follow up; however, some domains of the quality of life remained poor in comparison to healthy women [5]. In a study of 9491 Western European participants, Klaver et al. showed that women with increased TSH had scores of quality of life similar to those in euthyroid women [6]. In contrary, Shivaprasad et al., in their study of 244 women with hypothyroidism who were treated with thyroid hormone, found that despite the treatment, women had lower scores in six out of eight domains of quality of life [7]. Rakhshan et al. found that the spiritual health score of women with hypothyroidism was significantly lower than that in healthy women [8].

There are several methods to improve the quality of life in women with subclinical or clinical hypothyroidism. Werneck et al. found that a 16-week aerobic exercise could significantly improve different domains of quality of life, including physical functioning, general health, emotional health, mental, and physical components of quality of life [9].

Cognitive- behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the counseling methods that can help people to change their negative thoughts [10]. The use of CBT could improve the quality of life in patients with cardiac disease [11], hepatitis B [12], and women with breast cancer [13]. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the effect of CBT on quality of life in women with hypothyroidism. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effect of CBT on the quality of life of women who were under medication for hypothyroidism.

Methods

This was a randomized controlled trial involving 96 women with hypothyroidism in reproductive age. This study started in May 2019 and completed in September 2019. Women with the following criteria were recruited in this study: age 18–45 years, who had basic literacy, hypothyroidism diagnosed with laboratory tests and confirmed by an endocrinologist, women who acquired score less than 60 of the total score of quality of life questionnaire (SF36) and on medication for hypothyroidism. Women with the following criteria were excluded from the study: pregnancy, thyroid malignancy, mental illness such as depression and dementia, any chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease, smoking and drug abuse, history of stressful life events during the past six months. The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Ref No: 1397.968). This study was also registered in the Iranian Randomized Controlled Trials (IRCT) registry, (20,190,323,043,101 N1).

The following formula was used to calculate the sample size [14]:

The power of the study was set at 90% and α = 0.01, S2 = S1 = 11.9 and d = 10. The sample size was calculated to be 48 in each group.

Measures

In this study, a demographic questionnaire and the quality of life questionnaire (SF 36) was used to collect the data. The demographic questionnaire consisted of questions about age, age of spouse, employment, women and their husband’s educational attainment, economic status, any special diet, level of physical activity, duration of the disease, and obstetric history.

The SF36 questionnaire was designed by Ware and Sherbourne [15] and has 36 questions about the different domains of physical functioning (10 questions), role limitations due to the physical health problems (4 questions), bodily pain (2 questions), general health perception (6 questions), social functioning (2 questions), vitality (4 questions), mental health (5 questions), and role limitations due to emotional problems (3 questions). Questionnaire scores range from zero to 100, with a score of zero indicating the worst health status and a score of 100 indicating the best health status. This questionnaire was validated to use in Iran by Montazeri et al. in 2006 [16].

Randomization

Eligible women who provided consent were randomly assigned into two groups of CBT and control. We used block randomization with a block size of 4 and an allocation ratio of 1:1. For allocation concealment, each participant received a code and these codes were kept in the opaque sealed envelopes by the secretary of the clinic until the commencement of the intervention.

Intervention

The CBT group received eight sessions (a session per week) of counseling based on cognitive -behavioral therapy and the control group did not receive any intervention. The counseling session was held in a group of 12 and each session lasted 90 min. In the first session, participants introduced themselves, and one of the researchers (SR) explained about hypothyroidism, and how this disease can influence the life and activities of patients. The second session consisted of how women can reduce stress, according to the CBT. In the third session, after reviewing the homework, women received information about the incorrect thoughts and attitudes about hypothyroidism, and the relationship between negative thoughts and health. In the fourth session, participants received information about the reconstruction and change of irrational and negative attitudes and attributes and ineffective schemas about it. In this session, homework considered in the practice of muscle relaxation, verbal and nonverbal communication that enhance creativity and mastery over life and how to adopt with events and irrational beliefs about events.

In the fifth session, participants were trained about strengthening positive self- talk and visualizing successful relationships, cognitive challenges, and enhancing realism. In the sixth session, the researcher introduced muscle relaxation training for each muscle group individually, informing participants about stress, physical stress and how to increase awareness about physical symptoms of stress (mental-physical exercise training and imaging exercise). Participants also learned about diaphragmatic breathing exercises, how to identify negative thoughts and correct perceptions of stressful situations and introduce a thought assessment process. In the seventh session, participants learned about self-practicing for heat and heaviness, identifying logical and irrational self-talk, challenging negative self-talk, reconstruction and changing irrelevant negative thoughts, and demonstration of the effects of revised thinking and practicing reasoning thoughts. In the 8th session, participants received instructions about the logic of self-learning with visualization, positive self-induction, meditation, introducing effective coping steps and practice and finally the researcher summarized all sessions.

For ethical consideration, the control group received one compact disk on behavioral therapy at the end of the intervention. The blinding of the researcher and participants was not possible in this study. Although there was no blinding in this study, the researchers and participants did not know who was in which group until the intervention was started. Also, the statistician was not aware of the grouping.

Statistical analyses

We entered all data in the SPPS version 22. The normal distribution of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The independent t-test was used for testing numerical data between the two groups, while the chi-square test was used for comparing categorical data. For assessing variables that were measured twice, the ANCOVA was used for comparison. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

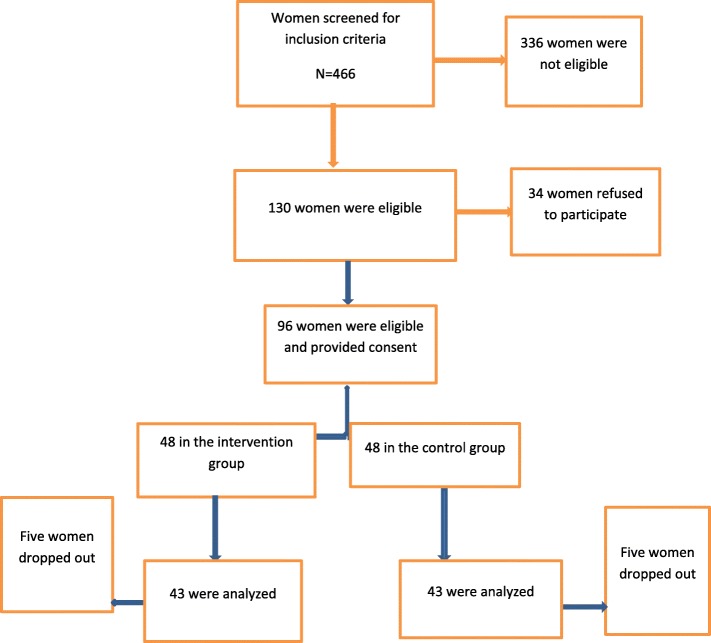

Forty-eight women were recruited in each group; however, five women in each group withdrew from the study because of personal reasons. The recruitment and retention of participants are shown in Fig. 1. The age of participants in the intervention group was significantly higher than that in the control group (35 ± 6.03 vs. 32.5 ± 7.42). Except for the age, the two groups did not show any significant difference in terms of body mass index, duration of disease, marital status, educational level of women and their spouses, employment and economic status (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Recruitment and retention of participants in the study

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants in the two groups

| Variables | CBT N = 43 |

Control N = 43 |

|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | ||

| Age (y) | 35.6 ± 6.03 | 32.5 ± 7.42 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.44 ± 4.9 | 27.56 ± 5.37 |

| Duration of illness (y) | 7.23 ± 7.05 | 4.95 ± 4.05 |

| N (%) | ||

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 5 (11.6) | 10 (23.3) |

| Married | 37 (86) | 33 (76.7) |

| Divorces | 1 (2.3) | 0 |

| Educational level | ||

| High school | 6 (14) | 10 (23.3) |

| Diploma | 19 (44.2) | 9 (20.9) |

| University education | 18 (41.9) | 24 (55.8) |

| Spouse’s education | ||

| High school | 7 (18.9) | 7 (21.2) |

| Diploma | 11 (29.7) | 13 (39.4) |

| University education | 19 (51.4) | 13 (39.4) |

| Employment | ||

| Housewife | 30 (69.8) | 33 (75.7) |

| Employee | 13 (30.2) | 10 (23.3) |

| Economic status | ||

| Poor | 5 (11.6) | 10 (23.3) |

| Moderate | 31 (72.1) | 30 (69.8) |

| Good | 7 (16.3) | 3 (7) |

CBT: cognitive- behavioral therapy

P for all variable was not significant except for age

Table 2 shows some general and obstetric characteristics of participants. Before the diagnosis of their disease, 44.2 and 34.9% of participants in the intervention group and the control group had physical activity, respectively. However, only 16.3% of women in the two groups had physical activity at the time of the study. Only a few women in the two groups received education or counseling about their disease (14 and 16.3% in the intervention and control groups, respectively).

Table 2.

General and obstetric characteristics of participants in the two groups

| Variables | CBT N = 43 |

Control N = 43 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | |||

| Physical activity before the disease | 19 (44.2) | 15 (34.9) | 0.25 |

| Physical activity at the present time | 7 (16.3) | 7 (16.3) | 0.61 |

| Special diet | 3 (7) | 4 (9.3) | 0.50 |

| Received education about the disease | 6 (14) | 7 (16.3) | 0.50 |

| Median (Range) | |||

| Number of pregnancies | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) | 2.0 (0.0–5.0) | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) |

| Number of deliveries | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) |

| Number of children | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) | 2.0 (0.0–3.0) |

Table 3 shows different domains of quality of life in two groups of CBT and control before and after the intervention. Although the physical functioning improved significantly in the CBT group after the intervention (from 59.6 ± 19.4 to 66.3 ± 21.8, p = 0.01), the difference between the CBT and control groups was not significant (p = 0.10). The two groups did not show any significant difference in physical health problems, social functioning and bodily pain after intervention.

Table 3.

Different domains of quality of life in two groups of CBT and control before and after intervention

| Variables | CBT N = 43 |

Control N = 43 |

P value between groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | |||||

| Before | After | Before | After | ||

| Physical functioning | 59.6 ± 19.4 | 66.3 ± 21.8 | 60.1 ± 16.4 | 60.9 ± 17.5 | 0.10 |

| P value before-after within each group | 0.01 | 0.66 | |||

| Role limitations due to the physical health problems | 30.8 ± 23.6 | 51.1 ± 29.3 | 38.3 ± 21.3 | 42.4 ± 20.7 | 0.05 |

| P value before-after within each group | < 0.0001 | 0.36 | |||

| Emotional health | 42.2 ± 14.5 | 53.9 ± 16.2 | 41.4 ± 15.4 | 42.9 ± 14.6 | 0.003 |

| P value before-after within each group | < 0.0001 | 0.49 | |||

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 18.6 ± 19.6 | 35.6 ± 32.03 | 17.05 ± 16.8 | 20.1 ± 19.4 | 0.01 |

| P value before-after within each group | 0.001 | 0.43 | |||

| Vitality and emotions | 33.6 ± 13.1 | 48.1 ± 15.8 | 36.1 ± 14.4 | 37.6 ± 13.6 | 0.001 |

| P value before-after within each group | < 0.0001 | 0.51 | |||

| Social functioning | 52.3 ± 22.3 | 63.3 ± 21.8 | 54.3 ± 18.6 | 54.6 ± 20.7 | 0.11 |

| P value before-after within each group | 0.92 | 0.03 | |||

| Bodily pain | 39.1 ± 14.06 | 57.3 ± 24.1 | 46.8 ± 19.3 | 51.1 ± 18.8 | 0.08 |

| P value before-after within each group | < 0.0001 | 0.12 | |||

| General Health | 30.6 ± 17.8 | 43.6 ± 18.4 | 29.3 ± 14.2 | 32.2 ± 17.3 | 0.004 |

| P value before-after within each group | < 0.0001 | 0.26 | |||

The scores of emotional health, emotional health problems, energy and emotions, and general health were significantly improved after the intervention in the CBT group as compared to those in the control group (p < 0.05). Overall physical health and overall spiritual health significantly improved in the CBT group as compared to the control group.

Discussion

This study was designed to evaluate the effect of CBT on the quality of life in women with hypothyroidism. The results showed that, although the scores of physical functioning, role limitations due to the physical health problems, social functioning, bodily pain, improved significantly after the intervention in the CBT group, the differences between the two groups were not significant. Hypothyroidism is a disease manifested with the reduction of thyroid hormone and may accompany some neuropsychiatric symptoms such as cognitive function and mood. In severe hypothyroidism, some symptoms similar to melancholia and dementia may occur [17]. In this regard, Joffe et al. found that CBT could improve depression as well as thyroid hormone levels in patients with overt and subclinical hypothyroidism [18].

In the present study, we found that although the scores of physical functioning and physical health problems improved in the CBT group, the difference between the two groups was not significant. Although we could not find any study on the effect of CBT on the physical functioning of hypothyroidism, White et al. in a large randomized controlled trial found that the adjuvant therapy of exercise and CBT could significantly improve chronic fatigue syndrome when added to medical care [19]. These results are consistent with our results.

In the present study, the scores of emotional health, emotional health problems, energy and emotions, and general health, were significantly improved after eight sessions of CBT in the CBT group as compared to the control group. In line with our findings, Nekouei et al. found that CBT could significantly improve the quality of life in patients with cardiovascular disease [11]. In a review, Lukkahatai et al. suggested that CBT is more likely to improve the psychological aspects of chronic illnesses than the physical and biological aspects [20]. Finally, Castro et al. randomized 93 patients with chronic pain into two groups of CBT and control, and found that CBT significantly improved depression, physical limitation, the general state of health and limitation by emotional aspects [21].

Strengths and limitation of the study

This is the first study to evaluate the effect of CBT on the quality of life in women with hypothyroidism. The results of this study, however, should be considered with caution in light of few limitations. First, we did not check the level of thyroid hormone before and after the intervention. Second, the responses to the questions of quality of life questionnaire may be affected by recall bias. Third, we only followed participants for eight weeks, further studies with longer follow-up are recommended. Fourth, we used block randomization with non-variable block size that may lead to predicting intervention. Lacking of blinding is another limitation. Although there was no blinding in this study, the researchers and participants did not know who was in which group until the intervention. And finally, because the SF36 questionnaire was completed by participants in the clinic and the researcher was there to resolve any ambiguity, it may have affected their responses.

Conclusion

This study showed that intervention with CBT can improve some aspects of quality of life, including emotional health, emotional health problems, energy and general health in a patient with hypothyroidism. Further studies with longer follow up are recommended.

Acknowledgements

This study was a master’s thesis of SR. We would like to thank all women who participated in this study. We confirm all patients/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person (s) described are not identifiable.

Abbreviation

- CBT

Cognitive- behavioral therapy

- TSH

Thyroid stimulating hormone

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: SR, PA, NH and HR. Data collection: SR. Data analysis and interpretation: EM, SR, PA Writing and finalizing the manuscript: PA, SR. All authors read and approved the final version of the study.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided by Ahvaz Jundishapaur University of Medical Sciences. The funder did not play any role in study design, data collection, data interpretation and writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data of this study will be available upon the request from the corresponding author.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (Ref No: 1397.968). Also, this study was registered in the Iranian Randomized Controlled Trials (IRCT), (20190323043101 N1) (URL: https://www.irct.ir/). All participants provided written informed consent before data collection.

Consent for publication

N/A

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sohaila Rezaei, Email: r.soheila@yahoo.com.

Parvin Abedi, Email: parvinabedi@ymail.com.

Elham Maraghi, Email: e.maraghi@gmail.com.

Najmeh Hamid, Email: n.hamid@scu.ac.ir.

Homaira Rashidi, Email: hrashidi2002@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Kostoglou-Athanassiou I, Ntalles K. Hypothyroidism - new aspects of an old disease. Hippokratia. 2010;14(2):82–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoki Yutaka, Belin Ruth M., Clickner Robert, Jeffries Rebecca, Phillips Linda, Mahaffey Kathryn R. Serum TSH and Total T4 in the United States Population and Their Association With Participant Characteristics: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES 1999–2002) Thyroid. 2007;17(12):1211–1223. doi: 10.1089/thy.2006.0235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aminorroaya A, Meamar R, Amini A, Feisi A, Tabatabae A. Faghii Imani E. Incidence of thyroid dysfunction in an Iranian adult population: the predictor role of thyroid autoantibodies: results from a prospective population-based cohort study l Eur J Med Res. 2017;22:21. doi: 10.1186/s40001-017-0260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delshad H, Amouzegar A, Mirmiran P, Mehran L, Azizi F. Eighteen years of continuously sustained elimination of iodine deficiency in the Islamic Republic of Iran: the vitality of periodic monitoring. Thyroid. 2012;22:415–421. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winther KH, Cramon P, Watt T, Bjorner JB, Ekholm O, Feldt-Rasmussen U, et al. Disease-specific as well as generic quality of life is widely impacted in autoimmune hypothyroidism and improves during the first six months of levothyroxine therapy. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156925. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klaver EI, van Loon HC, Stienstra R, et al. Thyroid hormone status and health-related quality of life in the LifeLines cohort study. Thyroid. 2013;23(9):1066–1073. doi: 10.1089/thy.2013.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shivaprasad C, Rakesh B, Dwarakanath CS. Impairment of health-related quality of life among Indian patients with hypothyroidism. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2018;22(3):335–338. doi: 10.4103/ijem.IJEM_702_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rakhshan M, Ghanbari A, Mostafavi I. A comparison between the quality of life and mental health of patients with hypothyroidism and Normal people referred to Motahari Clinic of Shiraz University of medical sciences. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 2017;5(1):30–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werneck Francisco Zacaron, Coelho Emerson Filipino, Almas Saulo Peters, Garcia Marília Mendes do Nascimento, Bonfante Heloina Lamha Machado, Lima Jorge Roberto Perrout de, Vigário Patrícia dos Santos, Mainenti Míriam Raquel Meira, Teixeira Patrícia de Fátima dos Santos, Vaisman Mário. Exercise training improves quality of life in women with subclinical hypothyroidism: a randomized clinical trial. Archives of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2018;62(5):530–536. doi: 10.20945/2359-3997000000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saripalli V. How does cognitive behavioral therapy work? Available at: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/296579.php. .

- 11.Nekouei ZK, Yousefy A, Manshaee G. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and quality of life: an experience among cardiac patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2012;1:2. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.94410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Riyahi N, Ziaee M, Dastjerdi R. The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy on quality of life among patients with hepatitis B. Mod Care J. 2018;15(3):e82748. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wojtyna E., Wiszniewicz A. EPA-1189 – Cognitive behavioral therapy and quality of life, level of depression and perceived social support among women with breast cancer. European Psychiatry. 2014;29:1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulseren S, Gulseren L, Hekimsoy Z, Cetinay P, Ozen C, Tokatliogla B. Depression, anxiety, health related quality of life, and disability in patients with overt and subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Arch Med Res. 2006;37(1):133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The short form health survey (SF-36): translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(3):875–882. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis JD, Tremont G. Neuropsychiatric aspects of hypothyroidism and treatment reversibility. Minerva Endocrinol. 2007;32(1):49–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joffe R, Segal Z, Singer W. Change in thyroid hormone levels following response to cognitive therapy for major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(3):411–413. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.3.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White PD, Goldsmith KA, Johnson AL, Potts L, Walwyn R, DeCesare JC, et al. Comparison of adaptive pacing therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, graded exercise therapy, and specialist medical care for chronic fatigue syndrome (PACE): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9768):823–836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60096-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukkahatai N, Inouye J, Thomason D, Kawi J, Leonard B, Connelly K. Integrative review on cognitive behavioral therapy in chronic diseases: the responses predictors. Iris Journal of Nursing & Care. 2019;1(5):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 21.CastroI MMC, DaltroI C, KraycheteI DC, Lopes J. The cognitive behavioral therapy causes an improvement in quality of life in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2012;70(11):864–868. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2012001100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data of this study will be available upon the request from the corresponding author.