Abstract

Objectives

The spread of Zika virus throughout Latin America and parts of the United States in 2016 and 2017 presented a challenge to public health communicators. The objective of our study was to describe emergency risk communication practices during the 2016-2017 Zika outbreak to inform future infectious disease communication efforts.

Methods

We conducted semi-structured telephone interviews with 13 public health policy makers and practitioners, 10 public information officers, and 5 vector-control officials from May through August 2017.

Results

Within the public health macro-environment, extended outbreak timeframe, government trust, US residence status, and economic insecurity set the backdrop for Zika communication efforts. Limited resources, staffing, and partnerships negatively affected public health structural capacity for communication efforts. Public health communicators and practitioners used a range of processes and practices to engage in education and outreach, including fieldwork, community meetings, and contact with health care providers. Overall, public health agencies’ primary goals were to prevent Zika infection, reduce transmission, and prevent adverse birth outcomes.

Conclusions

Lessons learned from this disease response included understanding the macro-environment, developing partnerships across agencies and the community, and valuing diverse message platforms. These lessons can be used to improve communication approaches for health officials at the local, state, and federal levels during future infectious disease outbreaks.

Keywords: communicable diseases, outbreaks, emerging infectious diseases, public health practice, preparedness, health communications

Public health communication for emergencies and disease outbreaks has improved since 2001 because of increasing use of a Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication framework in the public and private sectors, distillation and analysis of practitioner experiences, and an expanding scientific literature.1-3 Health emergencies such as the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and the 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak provided opportunities to test best practices in risk communication, uncover new best practices, and/or learn from the absence of best practices.4,5 The 2016-2017 Zika virus outbreak offers another opportunity to examine and enhance public health approaches to emergency risk communication.

In 2016, local mosquito-borne Zika virus cases were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (224 cases in Texas and Florida and 36 367 cases in US territories).6 Health authorities had to navigate incomplete and still-emerging information about Zika virus transmission, infection, and disease, including its global and local spread, its pathophysiology and clinical manifestations, and long-term consequences for affected infants and their families.7-11 Moreover, health communicators had to address viral transmission via sexual contact and mosquito bite.

With no vaccine or identified countermeasures available, communication about risk-reducing actions and infection prevention was particularly important. Research shows that public health communication can increase risk-reducing behaviors by raising awareness of health risks, increasing knowledge, and altering attitudes.12 Furthermore, tensions related to government or collective action vs individual choice or autonomy, and whether certain vector-control technologies are acceptable in the community, can also influence the acceptance of messaging and behavioral change. Uncovering how public health practitioners communicated information about the Zika virus and its health effects, individual infection prevention activities, and government and community interventions to reduce transmission can help improve future information campaigns.

The Zika response also occurred as health departments were increasingly constrained in efforts to connect with surrounding communities.13-15 Public health resources have declined since 2003, with reductions in staff and programming.16-23 Reduced levels of preparedness staff members affect local health department capacities.24 Documenting how health authorities conducted communication campaigns requiring a range of expertise in potentially underresourced contexts can inform a better understanding of factors that affect risk communication during public health emergencies.

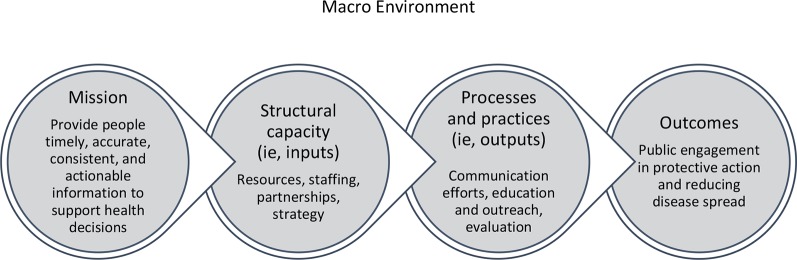

Framing the organization of this study was Handler et al’s model of the public health system, which positions a public health practice (eg, risk communication) in relation to its broader social and institutional context and its intended and/or actual health effects.25,26 Through its system perspective, the Handler et al model describes the forces impinging upon the conduct and effects of risk communication. By contrast, communication-specific models that compartmentalize the activity of public health information conveyance and uptake1 may inadvertently diminish the effects of the larger context in which human interchange takes place. The Handler et al model comprises the following elements:

Macro-level environment: overarching influences (eg, social, cultural, economic) that directly or indirectly affect the public health system;

Mission: goals of the public health system and how these goals are operationalized;

Structural capacity: tangible and intangible resources (ie, inputs) necessary for public health practice (eg, information, personnel, financing, facilities, social ties, leadership);

Processes and practices: methods practitioners use to identify, prioritize, and address public health issues (ie, outputs);

Outcomes: cumulative changes in short- and long-term health as a result of structural capacity and processes in the context of the macro-environment and mission.

The public health communication mission, the starting point for the communication efforts in question, is described in the CDC Zika Communication Planning Guide for States as: “Provide people timely, accurate, consistent and actionable information to support health decisions”27 (Figure). The purpose of our study was to identify key themes emerging from state and local public health practitioners’ experience communicating about Zika. Lessons learned may help health departments prepare and improve capacity to communicate during future outbreaks.

Figure.

Components of the public health communication system. Data source: Modified from Handler et al.25

Methods

The project team adopted a qualitative, descriptive study design to characterize state and local risk communication efforts launched in response to Zika. We used purposeful sampling to identify key informants (n = 67) with Zika communication expertise who could provide varied viewpoints from jurisdictions with high Zika case counts (ie, states with ≥100 official confirmed cases of Zika virus disease as of April 2017) or a high risk of local mosquito-borne transmission (ie, with competent vector species).6,28 After the first round of recruitment, we sought additional key informants in states and informant categories that were not adequately represented. Although our sample represented multiple states, we did not secure participation from 4 targeted states or territories. Twenty-eight key informants representing 17 states agreed to participate in semi-structured, qualitative interviews (Table 1). We conducted interviews with public health policy makers and practitioners (n = 13), public information officers (n = 10), and vector-control officials (n = 5) from May through August 2017. Informants were evenly split between state and local agencies. Interview questions addressed Zika-related communication efforts led or observed by informants, expert opinions on communication barriers and best practices, and perspectives on CDC’s role in risk communication.

Table 1.

Roles of key informants (n = 28) interviewed by telephone about emergency risk communication practices during the 2016-2017 Zika outbreak, United States, May–August 2017a

| Participant Category | No. of Informants | Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Public health policy makers and practitioners | ||

| Health department leadership | 5 | Health Administrator; Director (Office of Communication, Education, and Engagement); Department of Health Director; Executive Director; Commissioner |

| Public health practitioners | 8 | Director of Community Affairs, Epidemiologist; State Epidemiologist; Deputy Director for Population Health; Medical Director; State Public Health Veterinarian; Infectious Disease Physician |

| Public information officers | ||

| Communicators | 8 | Communications Manager; Public Information Officer; Public Education and Information Officer; Associated Commissioner for External Affairs; Public Health Education and Outreach Officer; Health Communications Specialist; Outreach Lead |

| Leadership | 1 | Director of Communications |

| Other | 1 | Marketing Director |

| Vector-control officials | ||

| Vector-control leadership | 2 | Executive Director; President |

| Practitioners | 3 | Director of Community Affairs; State Entomologist; Vector Control Specialist |

aKey informants were located in the following states: Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia.

We conducted 45-minute telephone interviews by using an interview guide with potential probing questions. Informants were told that their comments would not be attributed to them. When permitted, we tape recorded and transcribed interviews. We coded transcripts or detailed interview notes by using NVivo version 11.29 Researchers developed coding themes based on the interview guide and review of the interview transcripts and notes. Four members of the research team read each transcript or set of notes, and each member coded the transcripts and notes for a subset of themes to generate a set of communication capacities and approaches. The CDC Human Research Protection Office and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board determined this research exempt.

Results

Macro-Environment: Zika Virus in Context

Extended outbreak timeframe

Informants commented that as media engagement with the issue waned and perception grew that the threat had subsided, it was difficult to communicate about an outbreak that was no longer new but that required continued vigilance. Communicating the risks of Zika immediately after intensive communication campaigns for Ebola also proved difficult because of the waning novelty of disease threats.

Government trust

Several informants noted that for some populations they served, mistrust of government was a barrier to Zika message uptake. For example, one respondent noted that language barriers created distrust between the health department and a local Vietnamese community, requiring engagement with community leaders to help relay messages. In some communities, extant mistrust and suspicion of government activities—even in the absence of a crisis—complicated efforts to engage with constituents who were at risk for Zika. One informant said, “The people who live in this state have a tremendous distrust for government in general, and that’s just a longstanding tradition that we struggle with every day.” And although one mosquito-control officer reported high levels of trust because of familiarity with mosquito control in areas prone to mosquitoes, the officer noted some persons’ hesitancy to allow mosquito-control officers access to their property in areas where mosquito abatement was not conducted regularly.

US residence status

Many respondents cited anxiety about US residence status as a barrier to communicating effectively with populations at risk for Zika. Informants reported targeting Latino populations for Zika prevention messaging because of the widespread outbreak in South and Central America. This targeted population included some members who lacked US residence status. One informant noted, “It’s always that issue with fearfulness as far as messaging from government officials [goes], because you don’t know how many folks may be undocumented workers.” Another informant remarked, “They fear that we may be tied with [federal immigration officials] that may affect them or their family members.” Yet another informant reported, “There’s been a lot of local outreach to those communities to not open the door if anybody knocks, don’t talk to the government. And that’s something we’re struggling with—how to convey to them that we’re out there to help them.”

Economic insecurity

Informants highlighted challenges in communicating about Zika amid socioeconomic concerns. One informant noted, “[Our] people have no income to buy mosquito repellent…. They’re not going to go out and get it.” Some informants suggested that scientifically valid messages were inapplicable in low-resource communities. One informant noted, “There were a lot of very low-income areas where [people] leave their windows and doors open. They don’t have screens and they don’t have air conditioning.”

Structural Capacity: Resources, Staffing, and Partnerships

Resources

Adequate resources for communication activities were frequently highlighted as a key structural enabler of effective communication. Informants described what they could do with adequate internal support, explained how they shifted funds to various projects, or noted what they could do based on grant funding they were awarded. Zika-specific funding often enabled the communication outreach activities discussed during interviews.

Staffing

Although some health departments had sufficient staff members to support Zika emergency response communication activities in addition to routine public health work, others were burdened by responding to the outbreak, even those not in locations with active transmission. One informant stated, “We’re always stretched at the state health department, so resources to dedicate to these kinds of efforts are always hard to come by.” In some cases, public health and vector-control agencies relied on 1 person to manage communication for the Zika response. One informant said, “We need more manpower. I do the social media; I do the website; I do writing; I do graphic design; I do the strategy, [the] creative, the art direction and represent us with all of my counterparts at all levels of government…. It’s a lot for one person to do.”

Partners

Local government partners

Many informants representing health departments coordinated with local vector-control districts to eliminate sources of standing water, destroy mosquito habitats, and conduct spraying. City employees, including police, public works, and parks and recreation personnel, received training to eliminate mosquito breeding sources in public spaces. In some instances, the Zika response catalyzed new interagency partnerships. One informant said, “We have a new partnership with maternal and child health professionals within the health department that we’ve never worked with before. That has been really helpful in terms of getting the word out.” Another public health practitioner partnered with the city housing authority to identify risks for pregnant women in public housing, which led to the observation that these housing complexes lacked air conditioning and screens. Another partnership with the mayor’s office granted access to translators who could craft Zika prevention messages to air on Spanish-language radio stations.

Community- and faith-based organizations

Informants highlighted the importance of building partnerships with community-based organizations (CBOs) and faith-based organizations to improve communication with non-English speakers and other hard-to-reach populations. One informant said, “We have some language barriers with Haitian and Cuban populations ... so we’ve been working with translators on that and trying to get into the Haitian churches.” Another informant underscored the need to liaise with as many diverse CBOs as possible: “We use chambers of commerce and homeowners’ associations. We go to fishing and hunting clubs, women’s clubs, garden clubs. You name it, if it’s a club, we get to it. And we participate in as many of the community events as we can, from seafood festivals to fishing tournaments. We’ll set up a booth.”

Informants serving large Latino/a populations often collaborated with promotores de salud (ie, promotoras), Latino/a community health workers who work in Spanish-speaking communities. Although promotoras are not licensed health professionals, they are trained to provide education on a range of health issues. Informants reported training promotoras to deliver Zika prevention and control messages and then deploying them to communicate in clinics, physicians’ offices, nonprofit groups, and other agencies. One public health official remarked, “Promotoras are wonderful because they can bridge that gap between government and people who are worried that the government is questioning their immigrant status.”

CDC

Informants consistently viewed CDC officials as experts and depended on CDC to provide technical expertise on Zika. One informant remarked, “My paradigm is that CDC is the repository of expert knowledge about the disease itself and all of the science around it.” Informants also viewed CDC as an important source of guidance and communication resources that state and local public health groups could use to facilitate public engagement. Informants cited CDC infographics, pamphlets, and fliers as important materials used in response efforts. One informant said, “The guidance documents, the fact sheets, and all that kind of stuff has been really instrumental.” Even those who did not use CDC materials often used them as templates.

Processes and Practices: Education and Outreach

Informants developed and deployed communication materials using a range of approaches. Strategies addressed the needs of target populations; namely, pregnant women, non-English speakers, and highly mobile populations. Other efforts targeted community partners, including clinicians and other health care providers. Many informants also deployed a combination of communication strategies to target persons at the intersection of multiple vulnerabilities (eg, pregnant travelers) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

US public health engagement strategies for selected populations during the 2016-2017 Zika virus outbreak response, illustrative quotes from informants, and examples of activitiesa

| Population and Strategy | Selected Quotes and Examples |

|---|---|

| Pregnant women, their partners, and women of childbearing age | |

| Engaging women’s health care providers | “We put together Zika prevention kits, and distributed over 10 000 of those to OB-GYN [obstetrician-gynecologist] professionals across the state. And in this prevention kit, not only is there bug spray and condoms, but there’s all of our print information about preventing Zika and the Tip and Toss campaign.” |

| Addressing travel-related risks for pregnant women | “We definitely try to push, ‘You are a person of childbearing age. We want you to realize [that Zika] is something that can affect [your child if you] become pregnant within the next couple of months. Also, if your sexual partner is on this trip with you . . . that’s an additional risk.’” |

| Highly mobile populations | |

| Targeting recreational travelers | “We have [messages] that are targeted toward business travelers and then some that are specifically for the destination-wedding, honeymoon population, because that age group tends to be more in the childbearing ages.” |

| Communicating risk to families visiting high-risk locations | “Demographically, we know that the highest risk for Zika introduction will be [among those] visiting family in Mexico or South and Central America. . . . So our goal at this point is to make sure that [they] know that if they bring those viruses back to [this county], [it] could begin local transmission here, and that’s what we’re trying to prevent.” |

| Addressing risks unique to occupational travelers (eg, business travelers, migrant workers, volunteers) traveling to endemic regions |

|

| Non-English speakers | |

| Finding translators | “For our Spanish populations, we worked with that promotoras group—we sent them all the materials and asked for feedback on it . . . and we did the same thing with our materials that we translated in Vietnamese.” |

| Seeking diversity in visual messaging | “Some of [our] posters were in Spanish and English and featured Latinos in two of them, and then one was focusing on Caribbean people who potentially might travel or be from the Caribbean.” |

| Adapting existing communication materials | “I have found a lot of really good resources [from] other countries’ ministries of health to be very helpful because they have things in Spanish that I can repurpose, or they say things in Spanish that I can run by our Spanish-speaking staff and they will agree that that’s a better way to say it than how we’ve been saying it.” |

| Achieving multiplatform message dissemination | One health department partnered with Univision to organize telephone banks and disseminate Zika messages to Spanish speakers and health care providers via Spanish-language news programming. |

| Additional target populations | |

| Outreach to off-the-grid populations | “Colonias are notorious and rather plentiful, unfortunately. . . . Essentially, they’re not part of a city. They don’t have a lot of city services. They don’t necessarily always have paved roads. . . . They tend to be places where you can have a lot of standing water. You’ve got poor people. You’ve got plenty of mosquitoes. And those folks we found don’t really even listen to the news. So, they’re not even getting their news through the radio, let alone television.” |

| Engagement with lawmakers | “We actually went to the state house here and provided a presentation and overview to lawmakers so that they could respond to their constituent concerns, and they could let them know that . . . they had information and [the health department] was in touch with them.” |

aFrom interviews conducted with public health policy makers, public health practitioners, public information officers, and vector-control officials (n = 28) in 17 states (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia) during May–August 2017.

Table 3.

Types of communication materials used by US health officials during the 2016-2017 Zika virus outbreak response, illustrative quotes from informants, and examples of activitiesa

| Type | Description | Selected Quotes and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Printed materials, often available in English and Spanish, included prescription pads, door hangers, press releases, placards, stickers, posters/flyers, comics and coloring books, luggage tags, postcards, newspaper/magazine advertisements, and pamphlets. |

|

|

| Billboards | Billboards, although expensive, were an important means of communication to populations that might not have used communication channels such as radio and newspapers. | “[Billboards were] something that [residents] see every day as they travel to and from the businesses that they frequent.” |

| Information videos and webinars | Videos (online and DVD) and webinars were used to disseminate information about Zika virus and covered various topics, including pregnant women, travelers, and eliminating standing water on personal property. | One webinar “covered the whole topic of Zika and testing recommendations,” which was broadcast online and “available to anyone.” |

| Radio and television public service announcements | Public service announcements allowed health departments to reach various populations, including targeted cultural/ethnic and rural communities. | Airing these radio advertisements in the afternoon as people drove home from work (rather than in the morning) was considered more effective because the message to dump standing water was fresh when commuters arrived home. |

| Websites | Zika-specific web pages that were accessible directly via the state or local health department website were a “one-stop shop” for those looking for Zika-related information. These websites included data on the number of Zika cases in the state and information on what the health department was doing to combat the disease (eg, mosquito spraying activities). | “You could go [to the website] and look for information about Zika, what mosquito control is doing, what the department of health was doing. It was pretty much one-stop shopping for any residents in [our] county.” |

| Digital applications | Social media applications such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Nextdoor were considered integral to facilitating the dissemination of Zika-related information to the public—particularly for lower-resource health departments that lacked enough staff for more interpersonal activities—and were also used for rumor control. Social media was especially useful when trying to reach rural, isolated populations. |

|

aFrom interviews conducted with public health policy makers, public health practitioners, public information officers, and vector-control officials (n = 28) in 17 states (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia) during May–August 2017.

Outreach in the field

Door-to-door Zika campaigns allowed informants to communicate directly with the public and distribute educational materials (eg, door hangers, posters). Several informants used door-to-door activities to notify residents of Zika-related events, perform mosquito surveillance on the properties of travel-related cases, provide information on removing standing water and the importance of using mosquito repellent, and install screens to prevent mosquito bites. One jurisdiction reporting local transmission conducted door-to-door education among households near the residence of a person with Zika, conducted environmental assessments of nearby homes, and assessed neighbors for symptoms of infection. However, some informants noted that this approach involved “a lot of leg work,” reducing the likelihood of future use.

One informant identified street distribution as an effective method of risk messaging, noting that public health officials “[went] to street corners” to hand out materials. Another informant reported the need to spray in an area with hard-to-reach populations (eg, drug users, squatters), noting, “We pulled our cars up and met with the young men doing business on the corners and they handed out fliers to all their clients.”

Community meetings

Some informants held informational sessions with members of the public and the health care community or presented on Zika at community events (eg, religious gatherings, homeowners’ association meetings). One informant found that having “information booths at community events seemed to have really worked well.” Another informant held a series of “legislative workshops” where s/he “went to the state house … and provided a [Zika] … overview to lawmakers so that they could respond to their constituents’ concerns.”

Outreach to businesses and government organizations

Informants reported distributing fliers or working with airports, port authorities, Customs and Border Protection, schools, daycares, summer camps, district health offices, city housing, departments of social services, local parks and recreation offices, gas stations, grocery stores, movie theaters, and public transit buildings. One informant noted, “We’re going to go to street corners. We’re going to go to beauty salons. We’re going to have boots on the ground.” In one case, a partner airline helped disseminate Zika prevention messages among travelers visiting the Dominican Republic. Informants also worked with online radio services such as Pandora, state broadcasters’ associations, and iHeartMedia to broadcast Zika messages to populations at increased risk for Zika infection.

Outreach to health care providers

Providing accurate, up-to-date Zika-related messages to health care providers was a goal of many informants and encompassed various outreach measures. Some informants described efforts “to get physical things into [providers’] hands,” such as posters and palm cards; planning calls with local hospital associations; outreach via professional societies; and creation of a “provider communication group specifically focused on reaching out to providers.” One informant described using the Health Alert Network messaging system to all obstetricians and gynecologists licensed throughout the state and hiring a full-time physician to travel across the state to discuss Zika prevention with other clinicians. Another informant’s agency gave physicians Giant Microbes (https://www.giantmicrobes.com/us) stuffed toys depicting Zika virus to remind them to assess travel histories and test for Zika if indicated.

Evaluation of Activities

Few health and vector-control officials collected data on communication effectiveness, mainly because of time and resource constraints. One informant said, “We did not do any type of evaluation. We were just getting information out as quick as we could, and we don’t have any additional resources at all.” When evaluation was conducted, it took various forms, from informal to formal evaluation. However, most evaluation efforts were informal, taking advantage of existing data or anecdotal feedback to assess communication effectiveness and inform process improvements. Some informants monitored the frequency of Zika testing to determine whether Zika messaging reached target populations. Others used feedback from community partners performing vector surveillance and communication work to understand effectiveness. Still others cited process metrics, including data on website hits, click-through rates, and downloads, as well as the number of advertisements placed on radio stations. Multiple informants tracked the groups touched by community engagement efforts to quantify the spread of Zika messaging. Formal evaluation efforts often centered around public focus groups and workshops with response partners, which offered opportunities for structured data collection for the purpose of evaluation.

Outcomes: Reducing Disease Spread

Informants frequently referred to basic public health goals in describing the desired outcomes of their communication efforts. These goals included lowering the potential disease burden in their areas, preventing endemic transmission of the disease, and reducing the likelihood of adverse birth outcomes (Table 4). Awareness and knowledge about Zika virus—with the aim of increasing protective activities—was an important component of achieving this intended health outcome. Health education and promotion focused on the competent vectors, Zika symptoms, elimination of mosquito breeding habitats, mosquito bite prevention, prevention of sexual transmission, travel risks, potential effects for pregnant women and infants, and disease testing.

Table 4.

Intended outcomes for Zika virus–related communication efforts in the United States during the 2016-2017 Zika virus outbreak, illustrative quotes from informants, and examples of activitiesa

| Intended Outcome | Description | Selected Quotes and Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Prevent mosquito bites | Many jurisdictions focused on general mosquito bite prevention and not specifically on the mosquito species that transmits Zika as part of a wider campaign to prevent all mosquito-borne diseases (eg, West Nile virus). Actions encouraged included wearing mosquito repellent, wearing long pants and sleeves, and using window/door screens. |

|

| Reduce mosquito breeding sites | Mosquito-source reduction messages included how to identify areas where mosquitoes may lay eggs and tips on how to eliminate standing water, and often appealed to the civic duty of all to prevent disease transmission. |

|

| Prevent sexual transmission | Some participants highlighted the importance of potential importation of a travel case and subsequent spread via sexual contact and therefore emphasized safe-sex practices such as condom use. | “Our focus right now has been on travel and pregnant women and sexual transmission.” |

| Prevent travel-associated cases | Travel-related messages were targeted to incoming and outgoing travelers (often specifically pregnant women and women of childbearing age and their partners) and frequently focused on personal prevention methods. | “We provide key information about travel-related exposure. So, our goal at this point is to make sure that people that are traveling know what’s the risk if they travel and bring those viruses back to [redacted] county, then we could begin local transmission here, and that’s what we’re trying to prevent.” |

| Educate health care practitioners | Efforts included communication with members of the health system, specifically OB-GYNs [obstetricians/gynecologists] to provide education about Zika virus itself and Zika testing recommendations. | “We have a sizeable component that focuses on the medical community—making sure they are apprised of guidance on clinical management of Zika cases, diagnostics, assessment of cases, etc.” |

| Educate pregnant women, their partners, and women of childbearing age | Many messages warned pregnant women or those who thought they might be or become pregnant not to travel to places with ongoing Zika transmission, and also encouraged them to practice safe sex if their partner had recently traveled to an outbreak area. | “The other [emphasis] was not to travel to places where there was ongoing infection if pregnant or they thought they might be pregnant. . . . And some kind of secondary messaging for partners to take precautions during sex if you’ve traveled to that area.” |

aFrom interviews conducted with public health policy makers, public health practitioners, public information officers, and vector-control officials (n = 28) in 17 states (Alabama, Arizona, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia) during May–August 2017.

Discussion

During the Zika outbreak, broad social determinants of health such as economic stability and cultural context (eg, government trust and residence status) affected the response and modulated the uptake of risk-related messaging. Risk communicators must account for a range of social and economic conditions, as well as beliefs and values that shape public willingness to prioritize the health threat at hand and adopt protective public health measures.30-32 Although public health communicators confront many of these issues on a daily basis, some topics, such as trust in authorities and residence status, may play a growing role in future infectious disease emergencies, particularly in diseases originating outside the United States.

Adequate resources and staffing are vital components of successful risk communication; however, research shows that these resources have declined.13,33 When resources are limited, emergent crises pose new challenges (eg, insufficient staffing) for public health institutions. Furthermore, many forms of public engagement (eg, targeted advertising, door-to-door visits) are cost intensive. Study results reflect existing research and highlight the importance of public-sector and community partnerships to help overcome communication barriers, but maintaining these partnerships requires time, effort, and resources.34 During the Zika outbreak, public health officials needed to broaden communication efforts to effectively reach key populations but often lacked the resources to do so. Without changes to support structural capacity components outlined in this research, similar barriers may be expected in future outbreaks.

Diverse communication platforms and approaches are key to reaching target populations, but increasing the complexity of communication efforts requires additional resources. Zika communication efforts occurred via a range of platforms and channels. Activities that occurred during the Zika response provide a starting point for developing communication plans for future disease outbreaks. For example, social media is a cost-effective way of communicating with large populations, whereas communication with health care providers is an important way to reach targeted populations (eg, pregnant women). Deploying messages across multiple platforms requires communicators to tailor nuanced messages for target populations. Additionally, public health officials must consider metrics for evaluating response activities. Informants described desired outcomes but rarely identified metrics for evaluating the effect of their efforts. Looking forward, early identification of desired outcomes could help determine appropriate outcome evaluation methods for ensuring that intervention goals are met.35

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, although efforts were made to ensure a robust sample, included locales may not be representative of other settings. Second, sampling was designed to achieve a range of differing viewpoints but did not produce a statistically representative sample. Purposive sampling may be subject to error in researcher judgement, bias, and low generalizability. Finally, not all informants discussed each topic of interest. As a result, we did not report response rates or the numbers of informants who made specific comments.

Conclusions

Effective risk communication is grounded in appropriately worded, scientifically sound messages and is enhanced by a clear public health mission, adequate organizational capacity, robust communication activities and techniques, and linkages to discernible gains in population health. These components are important in efforts to promote public update of messages promoting risk-reducing behaviors. Lessons learned from the Zika response may improve efforts to prepare for and communicate about future public health emergencies. Our findings might also inform future experimental analyses of domestic emergency risk communication (eg, surveys) or formal evaluations by establishing common communication practices, resource needs, and context.

Footnotes

Author Note: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by CDC, the US Public Health Service, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors declared the following financial support with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The research was funded under contract #200-2016-92378 with CDC.

ORCID iD

Tara Kirk Sell https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8342-476X

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Crisis and emergency risk communication (CERC) manual. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/manual/index.asp. Published 2014. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 2. Tinker TL. Crisis Communications: Best Practices for Government Agencies and Non-profit Organizations. McLean, VA: Booz, Allen, Hamilton; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glik DC. Risk communication for public health emergencies. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;28(1):33-54. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schoch-Spana M., Brunson E., Chandler H. et al. Recommendations on how to manage anticipated communication dilemmas involving medical countermeasures in an emergency. Public Health Rep. 2018;133(4):366-378. 10.1177/0033354918773069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization Communicating Risk in Public Health Emergencies: A WHO Guideline for Emergency Risk Communication (ERC) Policy and Practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. http://www.who.int/risk-communication/guidance/download/en. Accessed October 25, 2018. [PubMed]

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika virus: 2016 case counts in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/reporting/2016-case-counts.html. Updated April 24, 2019. Accessed May 15, 2019.

- 7. Madad SS., Masci J., Cagliuso NV., Allen M. Preparedness for Zika virus disease—New York City, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(42):1161-1165. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6542a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kroelinger CD., Romero L., Lathrop E. et al. Meeting summary: state and local implementation strategies for increasing access to contraception during Zika preparedness and response—United States, September 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(44):1230-1235. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6644a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Likos A., Griffin I., Bingham AM. et al. Local mosquito-borne transmission of Zika virus—Miami-Dade and Broward counties, Florida, June–August 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(38):1032-1038. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6538e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Samuel G., DiBartolo-Cordovano R., Taj I. et al. A survey of the knowledge, attitudes and practices on Zika virus in New York City. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):98 10.1186/s12889-017-4991-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Piltch-Loeb R., Abramson DM., Merdjanoff AA. Risk salience of a novel virus: US population risk perception, knowledge, and receptivity to public health interventions regarding the Zika virus prior to local transmission. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0188666 10.1371/journal.pone.0188666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hornik RC. Public Health Communication: Evidence for Behavior Change. Mahwah, NJ: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Watson C., Watson M., Kirk Sell T. Federal funding for health security in FY2018. Health Secur. 2017;15(4):351-372. 10.1089/hs.2017.0047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schoch-Spana M., Nuzzo J., Ravi S., Biesiadecki L., Mwaungulu G Jr. The local health department mandate and capacity for community engagement in emergency preparedness: a national view over time. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(4):350-359. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schoch-Spana M., Ravi S., Meyer D., Biesiadecki L., Mwaungulu G Jr. High-performing local health departments relate their experiences at community engagement in emergency preparedness. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(4):360-369. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Watson CR., Watson M., Sell TK. Public health preparedness funding: key programs and trends from 2001 to 2017. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(S2):S165-S167. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, National Association of County and City Health Officials, Association of Public Health Laboratories, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists Impact of the redirection of public health emergency preparedness (PHEP) funding from state and local health departments to support national Zika response. http://www.naccho.org/uploads/downloadable-resources/Impact-of-the-Redirection-of-PHEP-Funding-to-Support-Zika-Response.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 18. National Association of County and City Health Officials Forces of change. http://nacchoprofilestudy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Full-Infographic.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 19. Willard R., Shah GH., Leep C., Ku L. Impact of the 2008-2010 economic recession on local health departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2012;18(2):106-114. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182461cf2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye J., Leep C., Newman S. Reductions of budgets, staffing, and programs among local health departments: results from NACCHO's economic surveillance surveys, 2009-2013. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2015;21(2):126-133. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mays GP., Hogg RA. Economic shocks and public health protections in US metropolitan areas. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 2):S280-S287. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reschovsky A., Zahner SJ. Forecasting the revenues of local public health departments in the shadows of the “Great Recession”. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22(2):120-128. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31828ebf8c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. National Association of County and City Health Officials The changing public health landscape: findings from the 2015 Forces of Change Survey. http://nacchoprofilestudy.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/2015-Forces-of-Change-Slidedoc-Final.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 24. National Association of County and City Health Officials Impact of public health emergency preparedness funding on local public health capabilities, capacity, and response. http://njaccho.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/report_phepimpact_july2015-Final.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 25. Handler A., Issel M., Turnock B. A conceptual framework to measure performance of the public health system. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(8):1235-1239. 10.2105/AJPH.91.8.1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schoch-Spana M., Sell TK., Morhard R. Local health department capacity for community engagement and its implications for disaster resilience. Biosecur Bioterror. 2013;11(2):118-129. 10.1089/bsp.2013.0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika communication planning guide for states. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/pdfs/Zika-Communications-Planning-Guide-for-States.pdf. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- 28. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zika virus: 2017 case counts in the US. https://www.cdc.gov/zika/reporting/2017-case-counts.html. Published 2018. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 29. NVivo [qualitative data analysis software] Version 11. Doncaster, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2015.

- 30. Lin L., Savoia E., Agboola F., Viswanath K. What have we learned about communication inequalities during the H1N1 pandemic: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:484 10.1186/1471-2458-14-484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Quinn SC., Thomas T., Kumar S. The anthrax vaccine and research: reactions from postal workers and public health professionals. Biosecur Bioterror. 2008;6(4):321-333. 10.1089/bsp.2007.0064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schoch-Spana M., Bouri N., Rambhia KJ., Norwood A. Stigma, health disparities, and the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: how to protect Latino farmworkers in future health emergencies. Biosecur Bioterror. 2010;8(3):243-254. 10.1089/bsp.2010.0021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Association of County and City Health Officials 2016 national profile of local health departments. http://nacchoprofilestudy.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ProfileReport_Aug2017_final.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed October 25, 2018.

- 34. Santibañez S., Lynch J., Paye YP. et al. Engaging community and faith-based organizations in the Zika response, United States, 2016. Public Health Rep. 2017;132(4):436-442. 10.1177/0033354917710212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lee CT., Greene SK., Baumgartner J., Fine A. Disparities in Zika virus testing and incidence among women of reproductive age—New York City, 2016. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2018;24(6):533-541. 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]