Abstract

Objectives

The influence of socioeconomic disparities on adults with pneumonia is not well understood. The objective of our study was to evaluate the relationship between community-level socioeconomic position, as measured by an area deprivation index, and the incidence, severity, and outcomes among adults with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).

Methods

This was an ancillary study of a population-based, prospective cohort study of patients hospitalized with CAP in Louisville, Kentucky, from June 1, 2013, through May 31, 2015. We used a race-specific, block group–level area deprivation index as a proxy for community-level socioeconomic position and evaluated it as a predictor of CAP incidence, CAP severity, early clinical improvement, 30-day mortality, and 1-year mortality.

Results

The cohort comprised 6349 unique adults hospitalized with CAP. CAP incidence per 100 000 population increased significantly with increasing levels of area deprivation, from 303 in tertile 1 (low deprivation), to 467 in tertile 2 (medium deprivation), and 553 in tertile 3 (high deprivation) (P < .001). Adults in medium- and high-deprivation areas had significantly higher odds of severe CAP (tertile 2 odds ratio [OR] = 1.2 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.06-1.39]; tertile 3 OR = 1.4 [95% CI, 1.18-1.64] and 1-year mortality (tertile 2 OR = 1.3 [95% CI, 1.11-1.54], tertile 3 OR = 1.3 [95% CI, 1.10-1.64]) than adults in low-deprivation areas.

Conclusions

Compared with adults residing in low-deprivation areas, adults residing in high-deprivation areas had an increased incidence of CAP, and they were more likely to have severe CAP. Beyond 30 days of care, we identified an increased long-term mortality for persons in high-deprivation areas. Community-level socioeconomic position should be considered an important factor for research in CAP and policy decisions.

Keywords: long-term mortality, 1-year mortality, late outcomes, disparities, inequalities, incidence, social inequalities, severity

Widening racial and socioeconomic inequalities across many diseases and health outcomes in the United States have been documented. Studies of pneumonia have found racial and socioeconomic inequalities in the incidence of lower respiratory tract infections,1 the incidence and outcomes of bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia,2-4 and all-cause mortality after pneumonia.5 These studies measured socioeconomic status with variables from the US Census Bureau at the census-tract level—large geographic separators used to break US counties into subpopulations of an average of 4000 persons. However, census-tract variables imprecisely measure individual resources and individual social status because the demographic characteristics of persons in a particular census tract can vary widely. Therefore, census tract–level variables may limit measurement of a person’s socioeconomic position.6

More robust measures of socioeconomic position have been created and used to better elucidate the relationships between socioeconomic characteristics and health outcomes. Using tools known as deprivation indices7—weighted, composite measures of community-level socioeconomic position (CLSEP) encompassing multiple spatial US Census variables—investigators have found disparities across many health outcomes, including hospital admission rates for pneumonia in the United Kingdom.8 A deprivation index exists for the United States at the block-group level—subpopulations of census tracts consisting of about 1000 persons. This index offers not only a more robust measure of CLSEP but also a more precise measure because of the reduced variability of characteristics in a block group.

To our knowledge, no studies have used a deprivation index to evaluate the relationships between CLSEP and clinical outcomes in adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP).6 The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of CLSEP on the incidence, severity, and clinical outcomes of hospitalized adults with CAP using a US Census block group–level deprivation index.

Methods

This was an ancillary study of the University of Louisville Pneumonia Study, a prospective, population-based cohort study of all consecutive hospitalized adults (aged (≥18 years) with CAP who were residents of Louisville, Kentucky (ie, Jefferson County, Kentucky), from June 1, 2014, through May 31, 2016. In-depth inclusion and exclusion criteria are described elsewhere.9 In the current study, we excluded persons residing in nursing homes due to the inability to link a patient with his or her residential US Census block group. In the event of rehospitalization during the study period, we included data only from each patient’s first hospitalization in the analysis. The Louisville Pneumonia Study was approved by the University of Louisville Human Subjects Research Program and Protection Office and the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board, the Robley Rex Veterans Affairs Medical Center Review Board, and the ethics boards of each participating institution.

Study Definitions

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)

This study included patients with CAP, which we defined as meeting the following 3 criteria: (1) presence of a new pulmonary infiltrate on chest radiograph and/or chest computed tomography scan at the time of hospitalization, defined by a board-certified radiologist’s reading; (2) at least 1 of the following: new cough or increased cough or sputum production, fever >37.8°C (100.0°F) or hypothermia <35.6°C (96.0°F), changes in leukocyte count (leukocytosis: >11 000 cells/mm3; left shift: >10% band forms/mL; or leukopenia: <4000 cells/mm3); and (3) no alternative diagnosis at the time of hospital discharge that justified the presence of criteria 1 and 2.

Community-level socioeconomic position (CLSEP)

We measured CLSEP by using a previously validated Area Deprivation Index (ADI).10,11 The ADI is a weighted composite score of an individual’s level of social and material deprivation based on the US Census block group of primary residence. We calculated the ADI by applying the coefficients from Singh11 at the block-group level using 2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates12 for each person in the study. We then categorized the ADI into race-specific tertiles for most analyses. Next, we categorized the ADI into tertiles for black and white race separately. We considered tertile 1 to be low deprivation, tertile 2 to be moderate deprivation, and tertile 3 to be high deprivation.

Outcome Variables

We evaluated the following outcomes—CAP incidence, severe CAP, early clinical improvement, mortality at 30 days, and mortality at 1 year (detailed hereinafter)—classified into 3 periods: (1) pre-care period: before initiation of therapy for CAP; (2) during-care period: from the start of therapy up to 30 days after hospitalization; and (3) post-care period: from 30 days after admission to 1 year after discharge.

Pre-Care Period

CAP incidence

We defined the incidence of CAP by using the number of unique patients hospitalized with CAP during the study period as the numerator and the 2015 ACS 5-year estimated population for Louisville as the denominator.

Severe CAP

We defined severe CAP by using the 2007 Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society major/minor criteria.13,14 Severe CAP includes the presence of 1 of 2 major criteria or 3 of 9 minor criteria. Major criteria include invasive mechanical ventilation and septic shock with the need for vasopressors; minor criteria include respiratory rate ≥30 breaths per minute, PaO2FiO2 ratio ≤250, multilobar infiltrates, confusion/disorientation, uremia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypothermia, or hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

During-Care Period

Early clinical improvement

We defined early clinical improvement if the American Thoracic Society 2001 criteria for clinical stability15 were met on or before the third day of hospitalization.

Mortality at 30 days

We defined 30-day mortality as death due to any cause at 30 days after admission.

Post-Care Period

Mortality at 1 year

We defined mortality at 1 year after discharge as death due to any cause after discharge from the index CAP hospitalization. We obtained data for post-discharge outcomes from the Kentucky Office of Vital Statistics, as done previously.9

Confounding Variables

We collected data on the following potentially confounding variables for inclusion in analyses based on a priori clinical and epidemiological considerations: age at admission, sex, body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), previous myocardial infarction or stroke, active cancer, history of renal disease, history of liver disease, and history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as documented through patient self-report or the medical record. We controlled for the presence of severe CAP in the evaluation of early clinical stability, 30-day mortality, and mortality at 1 year.

Quality Control and Data Management Plan

The quality control and data management plan is published elsewhere.9 Briefly, trained research associates collected and entered all clinical data onto a paper case-report form. Another trained research associate entered data from the paper form into REDCap, an electronic data management platform.16 A separate team of research associates evaluated missing and outlying data and corrected all errors. After all queries were resolved, we accepted the case into the database for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

To compare characteristics among patients in each race-specific ADI tertile, we calculated frequencies with percentages or medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). We calculated the numerator for the incidence rates by summing the total number of cases in each of the 3 race-specific ADI tertiles. We derived the denominator for each ADI tertile by summing the total adult populations by race-specific ADI tertile using ACS 2015 5-year estimates. We used the Pearson χ 2 trend test to evaluate the significance of trends in incidence rates across tertiles.

We evaluated CAP incidence risk areas by using geospatial maps and the Kulldorff spatial scan statistic.17 We assumed a Poisson distribution for the spatial scan analysis evaluating areas with high rates of CAP.

We evaluated the impact of the race-specific, ADI tertile-block group–level CAP incidence by using an Eigenvalue spatially filtered multilevel Poisson regression model.18,19 This model allowed us to account for spatial autocorrelation (defined a priori by Moran’s I) between the block-group rates, while adjusting for block group–level ACS variables, including median age, percentage of the population that is black/African American, and percentage of the population that is male.

To evaluate the impact of ADI tertiles on each clinical outcome under study while adjusting for the confounding variables listed previously, we used mixed-effects logistic regression models. For each model, we included the census-block group as a random effect. Continuous variables including age (years) and BMI (kg/m2) were mean-centered and scaled for inclusion in the models. We used R version 3.3.2,20 ArcGIS version 10.4,21 and SaTScan version 9.4.422 for all analyses. We considered P < .05 to be significant.

Results

The analysis included 6349 unique adults hospitalized with CAP. The ADI ranged from 9 to 135 (median, 107; IQR, 19) and differed significantly between black and white adults (black median, 115; IQR, 12; white median, 104; IQR, 17) (P < .001). Tertile 1 (low deprivation) included 1642 patients, tertile 2 (medium deprivation) included 3165 patients, and tertile 3 (high deprivation) included 1542 patients (Table).

Table.

Baseline characteristics of hospitalized patients aged ≥18 years with community-acquired pneumonia (n = 6439), by tertilea of the race-specific Area Deprivation Index, Louisville, Kentucky, June 1, 2014, through May 31, 2016b

| Variable | ADI Tertile 1 (n = 1642) | ADI Tertile 2 (n = 3165) | ADI Tertile 3 (n = 1542) | P Value c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 71 (22) | 67 (23) | 61 (20) | <.001 |

| Male, no. (%) | 793 (48.3) | 1443 (45.6) | 736 (47.7) | .15 |

| Black or African American race, no. (%) | 320 (19.5) | 640 (20.2) | 310 (20.1) | .83 |

| Medical history, no. (%) | ||||

| Previous myocardial infarction or stroke | 328 (20.0) | 674 (21.3) | 328 (21.3) | .87 |

| Alcoholic | 79 (4.8) | 171 (5.4) | 129 (8.4) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 439 (26.7) | 874 (27.6) | 454 (29.4) | .22 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 634 (38.6) | 1550 (49.0) | 870 (56.4) | <.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 177 (10.8) | 357 (11.3) | 172 (11.2) | .52 |

| Diabetes | 465 (28.3) | 1059 (33.5) | 474 (30.7) | .001 |

| HIV | 19 (1.2) | 46 (1.5) | 39 (2.5) | .01 |

| Neoplastic disease (active or within the past year) | 261 (15.9) | 440 (13.9) | 172 (11.2) | .001 |

| Renal disease | 453 (27.6) | 891 (28.2) | 411 (26.7) | .56 |

| Physical, laboratory, and radiographic findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.2 (9.6) | 27.3 (9.9) | 27.2 (11.7) | .44 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 117 (33) | 117 (36) | 116 (36) | .03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 59 (19) | 57 (19) | 57 (20) | .003 |

| Respiratory rate, no. of breaths/minute | 22 (6) | 22 (7) | 22 (6) | <.001 |

| Heart rate, no. of beats/minute | 104 (29) | 105 (27) | 108 (27) | <.001 |

| Temperature, °C | 37.2 (1.1) | 37.2 (1.1) | 37.1 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 19 (14.8) | 19 (15.0) | 17 (14.0) | <.001 |

| Serum glucose, mg/dL | 139 (68) | 143 (84) | 142 (89) | .004 |

| Hematocrit, % | 36.1 (8.0) | 35.7 (8.3) | 36.1 (9.0) | .04 |

| Serum sodium, mEq/L | 137 (6) | 137 (5) | 137 (6) | .001 |

| O2 saturation, % | 94 (5) | 94 (5) | 94 (4) | .01 |

| FiO2, % | 28 (15) | 28 (15) | 28 (15) | <.001 |

| PaCO2, mm Hg | 39 (14.9) | 41 (17.0) | 41.5 (16.5) | <.001 |

| PaO2, mm Hg | 71 (26.2) | 72 (30.0) | 73 (34.6) | .16 |

| pH | 7.4 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Serum bicarbonate, mEq/L | 7.4 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.1) | <.001 |

| Pleural effusion, no. (%) | 26 (5.5) | 26 (5.9) | 26 (6.0) | .07 |

| Severity of disease, no. (%) | ||||

| Severe CAPd | 545 (33.2) | 1160 (36.7) | 578 (37.5) | .02 |

| Altered mental status on admission | 231 (14.1) | 455 (14.4) | 251 (16.3) | .15 |

| Need for invasive mechanical ventilation or vasopressors on admission | 167 (10.2) | 427 (13.5) | 252 (16.3) | <.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 212 (12.9) | 512 (16.2) | 292 (18.9) | <.001 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

aTertile 1 is low-deprivation, high socioeconomic position. Tertile 2 is moderate-deprivation, moderate socioeconomic position. Tertile 3 is high-deprivation, low socioeconomic position. Deprivation is based on a previously validated area deprivation index.10,11

bData source: Louisville Pneumonia Study.9

cContinuous data (median) were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Categorical data (frequencies) were compared using the Pearson χ 2 test, with P < .05 considered significant.

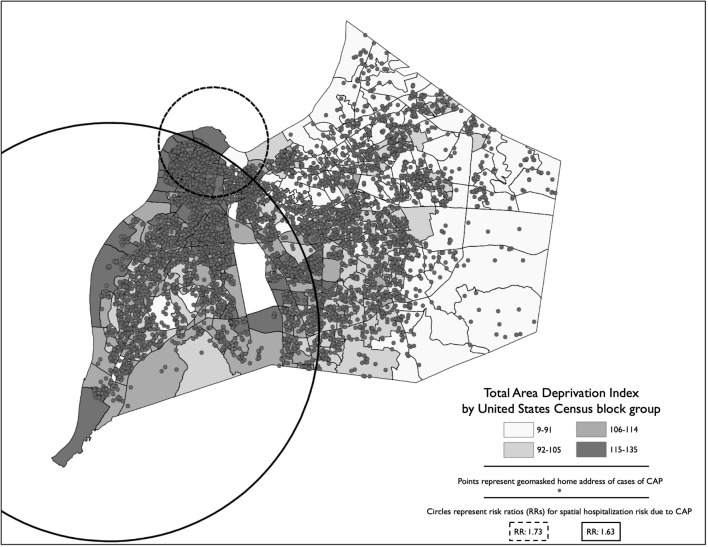

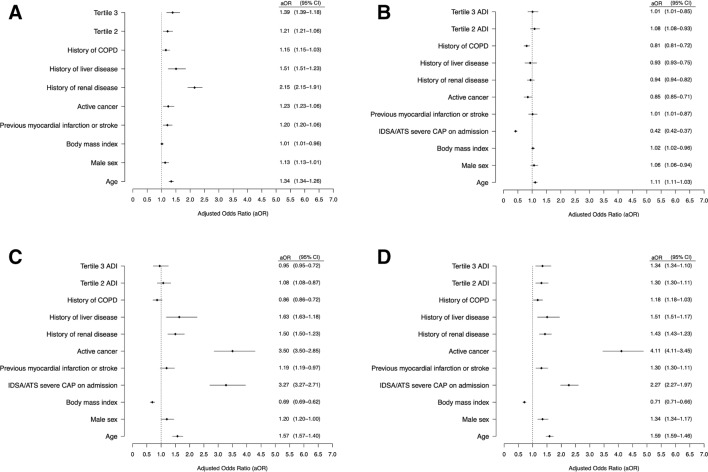

The hospitalization rate per 100 000 adults for CAP increased significantly across the 3 tertiles (tertile 1: 303; tertile 2: 467; tertile 3: 553) (P < .001). The number of CAP cases per block group increased 76% (95% confidence interval [CI], 61%-93%) for each 10-point increase in the block group–level ADI, after adjustment for spatial autocorrelation between block groups, block group–level median age, percentage of the population that is black/African American, and percentage of the population that is male. In the geospatial analysis of CAP risk areas in Louisville, we identified 2 areas with a significant increased risk of CAP (Figure 1). One risk zone encompassed the west side of the city (risk ratio [RR] = 1.63; 95% CI, 1.55-1.72; P < .001) and a smaller risk area was in the upper west area (RR = 1.73; 95% CI, 1.64-1.81; P < .001). We also found a significant relationship between race-specific ADI tertiles and severe CAP (tertile 2 odds ratio [OR] = 1.2 [95% CI, 1.1-1.4]; tertile 3 OR = 1.4 [95% CI, 1.2-1.6]) and 1-year mortality (tertile 2 OR = 1.3 [95% CI, 1.1-1.5]; tertile 3 OR = 1.3 [95% CI, 1.1-1.6]) (Figure 2). We found no significant relationships between race-specific ADI tertiles and early clinical improvement or 30-day mortality.

Figure 1.

Geospatial analysis of hospitalized adult patients aged ≥18 years with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) (n = 6349) incidence and areas of increased risk in Louisville, Kentucky, June 1, 2014, through May 31, 2016. Cases of CAP represent the geomasked location of the patient’s primary residence. Choropleth values represent quantile break points of the Area Deprivation Index,10,11 a weighted composite score of spatial deprivation using data from the 2015 US Census Bureau American Community Survey.12 Block-group shape geometries obtained from the US Census Bureau.23 Data source: Louisville Pneumonia Study.9

Figure 2.

Results of mixed-effects regression models evaluating race-specific Area Deprivation Index (ADI) tertiles on (A) IDSA/ATS severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), (B) early clinical improvement (≤3 days), (C) 30-day mortality, and (D) 1-year mortality among hospitalized adult patients aged ≥18 years (n = 6349) with CAP, Louisville, Kentucky, June 1, 2014, through May 31, 2016. Abbreviations: ATS, American Thoracic Society; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Data source: Louisville Pneumonia Study including adult (aged ≥18 years) hospitalized patients with CAP (n = 6349).9 Tertile 2 is moderate-deprivation, moderate socioeconomic position. Tertile 3 is high-deprivation, low socioeconomic position. These 2 tertiles are referent to Tertile 1, low-deprivation, high socioeconomic position. Deprivation is based on a previously validated ADI.10,11

Discussion

Our study found that lower CLSEP was associated with higher rates of hospitalization due to CAP. A similar relationship existed with lower CLSEP and increased severity of CAP at admission as well as with increased 1-year mortality.

Our data suggest a new paradigm for characterizing the relationship between CLSEP and CAP. We examined how CLSEP may affect patients with CAP during 3 periods. During the pre-care period, lower CLSEP (vs higher CLSEP) predicted a higher incidence of CAP and disease of higher severity. In the during-care period, CLSEP did not predict outcomes, perhaps because patients with CAP receive the same level of clinical care regardless of socioeconomic position. In the post-care period, the odds of death at 1 year were greater among persons with lower CLSEP than among patients with higher CLSEP.

Many hypotheses exist about the reasons for increased risk of respiratory infection among persons with low socioeconomic position. These hypotheses refer to such factors as differential health risk behaviors,24,25 increased comorbid and risk conditions,26,27 poor air quality,28 increased stress and lowered immunity,29-31 lack of access to preventive health care,25,32 and increased population density.3 These factors may be areas for targeted intervention and improved health policy decisions. The development of national guidelines for CAP has standardized clinical management of the disease in the United States.12,13 Our data support the idea that application of standardized clinical management to all persons, regardless of CLSEP, may result in equivalent outcomes in the during-care period. Hospitalized patients with CAP are at a higher risk of mortality 1 year after discharge than hospitalized patients without CAP.33-41 This increased mortality among patients with CAP may be due to inappropriate inflammatory responses to infection.37 Chronic inflammation may accelerate deterioration of comorbid conditions, which are already more prevalent among patients with lower socioeconomic position than among patients with higher socioeconomic position.

Areas at high risk of pediatric hospitalizations because of lower respiratory tract infections are in the urban core of cities, with lower rates of hospitalization in more affluent suburbs.1 Furthermore, CLSEP measures are associated with hospitalization rates in pediatric populations, suggesting that persons in lower CLSEP categories may have a higher risk of hospitalization due to CAP than persons in higher CLSEP categories.1 We found similar results in our adult population, adding credence to the importance of CLSEP as a critical health indicator.

This study had several strengths. First, we evaluated differences in CLSEP at the census block–group level, providing a closer proxy to a person’s socioeconomic position than that provided at the census-tract level. Second, we created race-specific tertiles of the ADI, which served to remove the underlying differences in race from the perspective of the ADI and increase the validity of our results.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, CLSEP (and therefore the ADI) may change over time, but we were not able to assess any changes in the ADI during the 1-year follow-up. Changes in CLSEP could bias the results because this study was a multi-year study. Second, persons living in high-deprivation areas often have low levels of health literacy and may not understand the signs and symptoms of CAP that require a visit to the hospital.32 If persons residing in high-deprivation areas do not realize they need hospital care or do not have access to hospital care, they may seek care in outpatient settings, not seek care at all, or die before being hospitalized. Because our study included only hospitalized patients with CAP, we could not evaluate the relationship between ADI and our outcomes of interest among patients with CAP who were not hospitalized. This limitation may be important because CLSEP may be intimately linked to perceived or actual access to medical care. Third, residents of Louisville may also not be representative of all persons in other geographic locations, thereby limiting the generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, investigators who use different measures of socioeconomic position from those used in our study may have different findings from ours on the relationship between CLSEP and the clinical outcomes of hospitalized patients with CAP. Our use of 1 measure for CLSEP further limited the generalizability of our findings.

Fourth, we may not have identified all hospitalized patients with CAP in Louisville; if a resident of Louisville obtained medical care at a hospital outside of Louisville, we would not have included that person in our study. If these persons were systematically different than those included, our results may have been biased. Fifth, we evaluated data only on all-cause 30-day and 1-year mortality. Death may occur at higher rates in high-deprivation areas than in low-deprivation areas because of several factors (eg, crime, lack of access to preventive care); we could not determine whether the deaths that occurred in the high-deprivation areas in our study were due to CAP or to other causes. If deaths were due to reasons other than CAP, our conclusions may be less reliable. Sixth, our estimate of socioeconomic position was at an aggregate level and not at the patient level; therefore, our estimates could be biased. Finally, although our spatial analytic approach allowed for correction of autocorrelation spatially, it was limited by the number of aggregate census-level variables included in the model; as such, it may have residual confounding.

Areas of Future Research

Future work in this area is critical. Although we used US Census block group–level variables to calculate race-specific ADI, they may not have accounted for all individual-level effects of these variables. Future studies should collect data on indicators of socioeconomic position among patients to account for potential differential effects of the environment and of patients. Ideally, items from the US Census could be used at the individual level to directly compare spatial measures with individual measures. Because socioeconomic position can change over time, longitudinal follow-up is also necessary. Adjusting or stratifying by socioeconomic position in observational studies of CAP is warranted given the relationship between CLSEP and the incidence, severity, and some outcomes identified in this study. Further work is needed to understand the effects of a person’s socioeconomic position. A better understanding of the relationships between socioeconomic position and health may facilitate the development of improved, targeted, and cost-effective interventions and policy decisions.

Conclusion

We found significant associations between lower CLSEP and increased incidence and severity of CAP. We found no significant association between CLSEP and early clinical improvement or 30-day mortality. Beyond 30 days of care, however, disparities in clinical outcomes emerged, resulting in increased long-term mortality for persons in high-deprivation areas. Because CAP is a major cause of death worldwide, social and economic determinants of disease should be a focus of local, national, and international policy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Wallis, PhD, at the University of Louisville School of Public Health and Information Sciences Department of Epidemiology and Population Health for her insight into local and global health disparities; and Doug Lorenz, PhD, at the University of Louisville School of Public Health and Information Sciences Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics for his insight into alternative statistical methodologies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors declared no financial support with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Timothy L. Wiemken https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8251-3007

References

- 1. Beck AF., Florin TA., Campanella S., Shah SS. Geographic variation in hospitalization for lower respiratory tract infections across one county. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(9):846-854. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burton DC., Flannery B., Bennett NM. et al. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in the incidence of bacteremic pneumonia among US adults. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1904-1911. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.181313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feemster KA., Li Y., Localio AR. et al. Risk of invasive pneumococcal disease varies by neighbourhood characteristics: implications for prevention policies. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141(8):1679-1689. 10.1017/S095026881200235X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Flory JH., Joffe M., Fishman NO., Edelstein PH., Metlay JP. Socioeconomic risk factors for bacteraemic pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137(5):717-726. 10.1017/S0950268808001489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hausmann LR., Ibrahim SA., Mehrotra A. et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in pneumonia treatment and mortality. Med Care. 2009;47(9):1009-1017. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181a80fdc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krieger N., Williams DR., Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341-378. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krieger N., Chen JT., Waterman PD., Rehkopf DH., Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measure—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655-1671. 10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hawker JI., Olowokure B., Sufi F., Weinberg J., Gill N., Wilson RC. Social deprivation and hospital admission for respiratory infection: an ecological study. Respir Med. 2003;97(11):1219-1224. 10.1016/S0954-6111(03)00252-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ramirez JA., Wiemken TL., Peyrani P. et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(11):1806-1812. 10.1093/cid/cix647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Knighton AJ., Savitz L., Belnap T., Stephenson B., VanDerslice J. Introduction of an area deprivation index measuring patient socioeconomic status in an integrated health system: implications for population health. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2016;4(3):1238. 10.13063/2327-9214.1238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Singh GK. Area deprivation and widening inequalities in US mortality, 1969-1998. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(7):1137-1143. 10.2105/AJPH.93.7.1137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. US Census Bureau American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs. Accessed February 3, 2020.

- 13. Mandell LA., Wunderink RG., Anzueto A. et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27-S72. 10.1086/511159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aliberti S., Zanaboni AM., Wiemken T. et al. Criteria for clinical stability in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(3):742-749. 10.1183/09031936.00100812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Niederman MS., Mandell LA., Anzueto A. et al. Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1730-1754. 10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.at1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harris PA., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kulldorff M., Heffernan R., Hartman J., Assunção R., Mostashari F. A space-time permutation scan statistic for disease outbreak detection. PLoS Med. 2005;2(3):e59. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Griffith DA., Chun Y. An eigenvector spatial filtering contribution to short range regional population forecasting. Econ Business Letters. 2014;3(4):208-217. 10.17811/ebl.3.4.2014.208-217 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Park YM., Kim Y. A spatially filtered multilevel model to account for spatial dependency: application to self-rated health status in South Korea. Int J Health Geogr. 2014;13:6 10.1186/1476-072X-13-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. R [computer program] Vienna, Austria: R Corp; 2019.

- 21. ArcGIS Desktop [computer program] Redlands, CA: Esri; 2018.

- 22. SaTScan [computer program] Version 9.4.4. Boston: SaTScan; 2005.

- 23. US Census Bureau 2018 TIGER/:Line shapefiles: block groups. https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2018&layergroup=Block+Groups. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- 24. Hutchins SS., Fiscella K., Levine RS., Ompad DC., McDonald M. Protection of racial/ethnic minority populations during an influenza pandemic. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 2):S261-S270. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jhanjee I., Saxeena D., Arora J., Gjerdingen DK. Parents’ health and demographic characteristics predict noncompliance with well-child visits. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2004;17(5):324-331. 10.3122/jabfm.17.5.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clark LT., Ferdinand KC., Flack JM. et al. Coronary heart disease in African Americans. Heart Dis. 2001;3(2):97-108. 10.1097/00132580-200103000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Polednak AP. Racial differences in mortality from obesity-related chronic diseases in US women diagnosed with breast cancer. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(4):463-468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ghio AJ. Particle exposures and infections. Infection. 2014;42(3):459-467. 10.1007/s15010-014-0592-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aiello AE., Simanek AM., Galea S. Population levels of psychological stress, herpesvirus reactivation and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):308-317. 10.1007/s10461-008-9358-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Brunner E. Stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ. 1997;314(7092):1472-1476. 10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Culhane JF., Rauh VA., Goldenberg RL. Stress, bacterial vaginosis, and the role of immune processes. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2006;8(6):459-464. 10.1007/s11908-006-0020-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Larson K., Halfon N. Family income gradients in the health and health care access of US children. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(3):332-342. 10.1007/s10995-009-0477-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sandvall B., Rueda AM., Musher DM. Long-term survival following pneumococcal pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(8):1145-1146. 10.1093/cid/cis1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mangen MJ., Huijts SM., Bonten MJ., de Wit GA. The impact of community-acquired pneumonia on the health-related quality-of-life in elderly. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):208 10.1186/s12879-017-2302-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koivula I., Stén M., Mäkelä PH. Prognosis after community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly: a population-based 12-year follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(14):1550-1555. 10.1001/archinte.159.14.1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaplan V., Clermont G., Griffin MF. et al. Pneumonia: still the old man's friend? Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(3):317-323. 10.1001/archinte.163.3.317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guertler C., Wirz B., Christ-Crain M., Zimmerli W., Mueller B., Schuetz P. Inflammatory responses predict long-term mortality risk in community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(6):1439-1446. 10.1183/09031936.00121510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eurich DT., Marrie TJ., Minhas-Sandhu JK., Majumdar SR. Ten-year mortality after community-acquired pneumonia. A prospective cohort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(5):597-604. 10.1164/rccm.201501-0140OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Carriere KC., Jin Y., Marrie TJ., Predy G., Johnson DH. Outcomes and costs among seniors requiring hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia in Alberta. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):31-38. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bruns AH., Oosterheert JJ., Cucciolillo MC. et al. Cause-specific long-term mortality rates in patients recovered from community-acquired pneumonia as compared with the general Dutch population. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(5):763-768. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03296.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bordon J., Wiemken T., Peyrani P. et al. Decrease in long-term survival for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2010;138(2):279-283. 10.1378/chest.09-2702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]