Abstract

Background

The World Health Organization characterized the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a pandemic on March 11th. Many clinical trials on COVID-19 have been registered, and we aim to review the study characteristics and provide guidance for future trials to avoid duplicated effort.

Methods

Studies on COVID-19 registered before March 3rd, 2020 on eight registry platforms worldwide were searched and the data of design, participants, interventions, and outcomes were extracted and analyzed.

Results

Three hundred and ninety-three studies were identified and 380 (96.7%) were from mainland China, while 3 in Japan, 3 in France, 2 in the US, and 3 were international collaborative studies. Two hundred and sixty-six (67.7%) aimed at therapeutic effect, others were for prevention, diagnosis, prognosis, etc. Two hundred and two studies (51.4%) were randomized controlled trials. Two third of therapeutic studies tested Western medicines including antiviral drugs (17.7%), stem cell and cord blood therapy (10.2%), chloroquine and derivatives (8.3%), 16 (6.0%) on Chinese medicines, and 73 (27.4%) on integrated therapy of Western and Chinese medicines. Thirty-one studies among 266 therapeutic studies (11.7%) used mortality as primary outcome, while the most designed secondary outcomes were symptoms and signs (47.0%). Half of the studies (45.5%) had not started recruiting till March 3rd.

Conclusion

Inappropriate outcome setting, delayed recruitment and insufficient numbers of new cases in China implied many studies may fail to complete. Strategies and protocols of the studies with robust and rapid data sharing are warranted for emergency public health events, helping the timely evidence-based decision-making.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health emergency, Therapeutic effect, Trial characteristics, Trial registration

1. Introduction

Coronaviruses are a large family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).1 Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) occurred in December 2019 and the first case was reported in Wuhan, China.2 On January 31, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced that the new coronavirus epidemic constituted a public health emergency of international concern and characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11.3 As of April 28, 3,138,115 people were confirmed infected with COVID-19 worldwide in 210 countries and territories with cases.4 While carrying out public health control and clinical management, Chinese government also encouraged speeding up clinical trials of new drugs, and it was necessary to promptly launch them into the frontline of treatment, improve cure and reduce death.5 As there is no specific treatment for COVID-19, and the main management is for symptomatic treatment and supportive care, clinical evidence is urgently needed to support clinical decision-making. Researchers in China reacted quickly, and the first clinical trial was registered in the China clinical trials registry on January 23, 2020. Following a short period, more than 200 clinical trials have been registered, involving a variety of therapeutic approaches.6 Facing the increasing ongoing trials, it would be important to review the research questions and characteristics of these studies to inform clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of COVID-19.

Therefore, our aim is to investigate the characteristics of the registered studies in the early period after the outbreak of COVID-19, providing guidance for future trials and avoiding duplicated effort worldwide.

2. Methods

2.1. Search strategy

All the clinical studies on COVID-19 registered before March 3rd 2020 on the trial registry platforms were retrieved, including the United States ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicalTrials.gov), Chinese clinical trial registry (ChiCTR) (http://www.chictr.org.cn), Acupuncture-Moxibustion Clinical Trial Registry (http://www.acmctr.org/index.aspx), Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (http://www.anzctr.org.au), Japan Primary Registries Network (https://jrct.niph.go.jp), the United Kingdoms’ ISRCTN registry (http://www.isrctn.com), Clinical Trials Registry-India (http://ctri.nic.in) and EU Clinical Trials Register (https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu). The search terms included COVID-19, Corona Virus Disease 2019, novel coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, and SARS-CoV-2.

2.2. Data extraction

Nine authors (MX, YJ, YZ, YYZ, YXS, ZYT, XYJ, QBJ, MY) abstracted data, including registration number and date, title, e-mail, leading institutions, country and province, setting, ethic information, funding, design, study objectives, anticipated start date, interventions and control, population, sample size, recruiting status and outcomes. We also checked the numbers of confirmed cases in China from the official website of the National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China.7 All abstracted data were entered into a pre-defined data extraction sheet.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The quantitative description and figures were conducted by MY and YXS with Microsoft Excel 2016 and the GraphPad Prism 6.

3. Results

3.1. Basic information of registered studies

After searching on the registries, 406 records were retrieved and after removing duplicates, 393 were eligible and included in the analysis. Three hundred and twenty-one studies were from ChiCTR, 69 from the Clinicaltrials.gov, and 3 from Japanese Registry. No records were found from other registries.

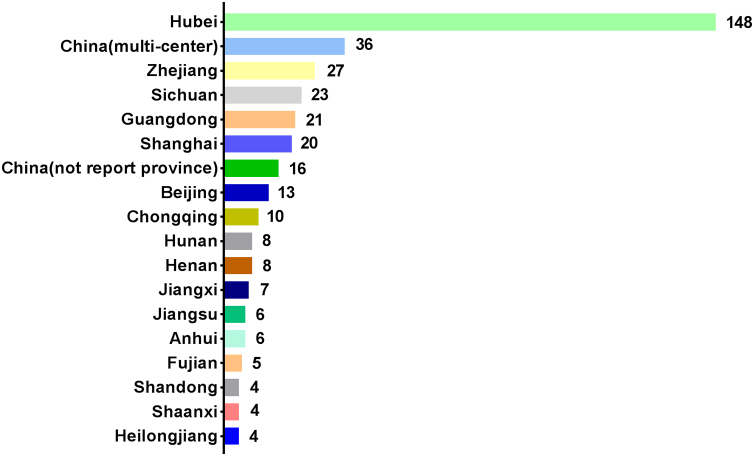

The countries hosting the trials were China (380 studies), Japan (3), France (3), the US (2), 3 international collaboration studies, and 2 studies with no country origin (Supplementary Figure 1). Among those 380 studies in China, 36 studies were supposed to be conducted in more than 2 provinces, and 328 studies each in one province (26 provinces in total) and 16 studies did not provide information about the place. One study was an online survey investigating quality of life of Chinese residents during or after the outbreak of COVID-19.

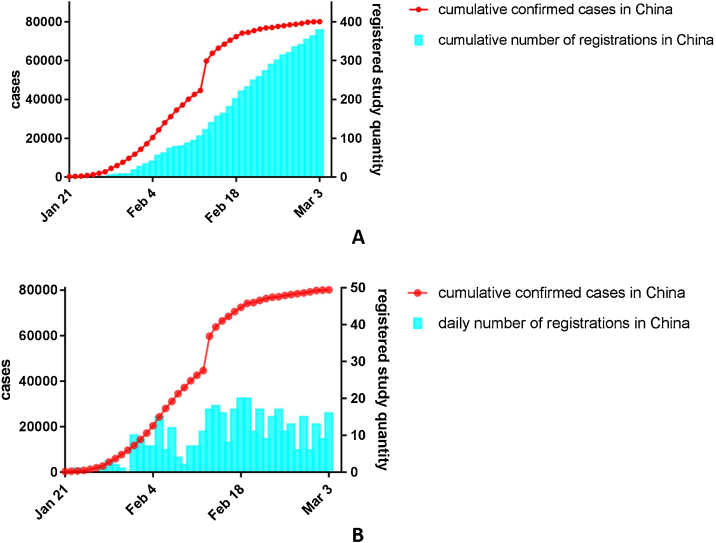

Fig. 1 demonstrates the trend of confirmed COVID-19 cases in China, and the number of registered studies. From the date of first trial registered to March 3rd, the number of confirmed cases was increasing and reached 59 084. Meanwhile, the number of registered studies were also increased to 393, with a daily number of registrations range from 1 to 20.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative confirmed COVID-19 cases along with cumulative number of registered studies (A) and daily registrations (B) in China.

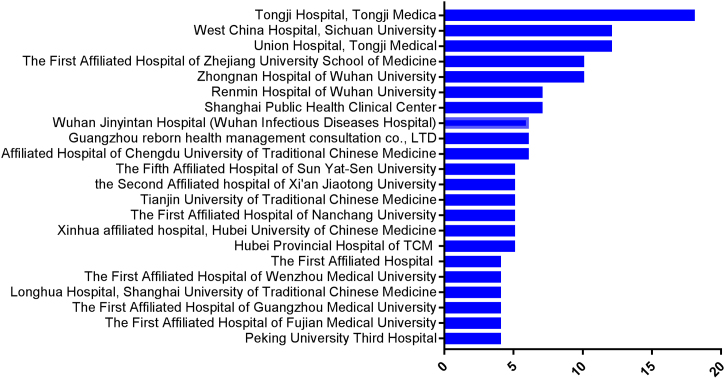

Except 10 studies that did not report the institutional information, 198 institutions were planning the studies on COVID-19 worldwide, and 22 had registered for more than 4 studies (Supplementary Figure 2). Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College at Huazhong University of Science and Technology was on the top of the rank with 18 registrations, the second were West China Hospital of Sichuan University, and the First Hospital Affiliated to Zhejiang University's Medical School, registered 12 studies, respectively.

3.2. Study design of registered studies

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies. Of the 393 studies, 266 were therapeutic studies (67.7%). In the 266 studies, 184 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), followed by 34 single arm trials, 27 controlled clinical trials, and 21 observational studies. In addition to the prevention, diagnosis, and prognosis studies, 67(17.0%) had other aims shown in the notes of Table 1. There were 202 (51.4%) RCTs. Among them, one was using an adaptive design testing remdesivir. The anticipated start date or the study execution time and registration date on the registrations were compared in RCTs, and 95 of them started the studies before registration, indicating retrospective registrations.

Table 1.

The Characteristics of the Registered Studies From Eight Registries

| Items | Details | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aim | Prevention | 16 | 4.1 |

| Therapeutic evaluation | 266 | 67.7 | |

| Diagnosis | 25 | 6.4 | |

| Prognosis | 19 | 4.8 | |

| Othersa | 67 | 17.0 | |

| Setting | Hospital | 363 | 92.4 |

| Community | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Others (university, online and research institute) | 3 | 0.8 | |

| NA | 23 | 5.9 | |

| Study type | RCTs | 202 | 51.4 |

| CCTs | 31 | 7.9 | |

| Single arm trials | 23 | 5.9 | |

| Observational studies | 96 | 24.4 | |

| Cross-sectional studies | 16 | 4.1 | |

| Diagnostic tests | 18 | 4.6 | |

| Others (basic science/factorial/NA) | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Sample size | ≤100 | 206 | 52.4 |

| 101–300 | 106 | 27.0 | |

| 301–500 | 43 | 10.9 | |

| 501–1500 | 21 | 5.3 | |

| 1500+ | 14 | 3.6 | |

| NA | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Populations | People exposed to patients | 38 | 9.7 |

| Suspected infection | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Confirmed or suspected infection | 15 | 3.8 | |

| Mild or moderate | 121 | 30.8 | |

| Moderate or severe | 6 | 1.5 | |

| Severe or critical illness | 72 | 18.3 | |

| Confirmed patients (without details for stage or all stages included) | 96 | 24.4 | |

| Confirmed patients with complications | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Rehabilitation | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Special population (children, neonates, women, maternal) | 6 | 1.5 | |

| Other diseases without COVID-19 | 6 | 1.5 | |

| Othersb | 8 | 2.0 | |

| Recruitment status | Not yet recruiting | 179 | 45.5 |

| Recruiting | 192 | 48.9 | |

| Completed | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Suspended | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Expanded accessc | 1 | 0.3 | |

| NA | 14 | 3.6 | |

| Interventions (therapeutic studies) | Western medicine | 177 | 66.5 |

| Chinese medicine | 16 | 6.0 | |

| Integrated therapy | 73 | 27.4 | |

| Comparisons (therapeutic studies) | Conventional therapy | 122 | 45.9 |

| Antiviral drugs | 26 | 9.8 | |

| Placebo | 28 | 10.5 | |

| Blank | 11 | 4.1 | |

| No control group | 47 | 17.7 | |

| Multiple controls | 14 | 5.3 | |

| Othersd | 18 | 6.8 | |

| Funding source | Government | 106 | 27.0 |

| Hospital | 74 | 18.8 | |

| University/Research institute/Academic association | 22 | 5.6 | |

| Multiple funding | 18 | 4.6 | |

| Industry | 44 | 11.2 | |

| Self-raised | 105 | 26.7 | |

| No funding | 7 | 1.8 | |

| NA | 17 | 4.3 | |

| Ethical approval | Yes | 268 | 68.2 |

| Unclear | 125 | 31.8 |

Other aims: epidemiology research, description of clinical or imaging characteristics, investigation on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) syndrome.

Other populations: health or suspected infectious people, COVID-19 patients and other types of pneumonia, COVID-19 patients and other influenza patients.

Expanded access: currently available for this investigational treatment, and patients who are not participants in the clinical study may be able to gain access to the drug, biologic, or medical device being studied.

Other comparisons: different dosage or duration of the tested intervention, “historical comparison” (without details), γ-Globulin, bag-valve mask oxygenation Assisted tracheal intubation, psychological intervention (without details), Chinese medicine.

NA, not available; RCT, randomized controlled trial; CCT, controlled clinical trial.

The sample size of 312 studies was less than 300 subjects, which made up 79.4% of the registered studies. The average sample size was 1061 and ranged from 8 to 150,000 per study. The population included in studies were mainly confirmed COVID-19 patients (308 studies, 78.4%), and other populations such as people exposed to patients, suspected infection cases, the combined participants of confirmed and suspected infection cases, rehabilitation people and other disease without COVID-19 were also involved in the registered studies (85 studies, 21.6%). One hundred and seventy-nine studies (45.5%) had not started recruiting on March 3rd, 192 studies (48.9%) were recruiting and one study on eculizumab was on expanded access. The three completed studies were cohort study for therapeutic effect, cross-sectional study for the psychological status investigation, and the prognosis study of computerized tomography score predicting mortality.

Among the retrieved studies, 268 (68.2%) registered on ChiCTR attached the ethical approval documents and 62 (15.8%) didn’t. The ethical approval information could not be checked for 63 other studies (16.0%) registered on clinicaltrials.gov or Japanese Registries.

The interventions and comparisons of 266 therapeutic studies are shown in Table 1. One hundred and seventy-seven studies (66.5%) were testing Western medicine and others were for Chinese medicine (16 studies, 6.0%) or integrative therapy of both (73 studies, 27.4%). In terms of the comparisons, 122 therapeutic studies (45.9%) used conventional therapy as control intervention, following to the guidance issued by National Health Commission and National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Antiviral drugs, placebo, blank, multiple controls, and others were the comparisons used in the studies (Table 1).

3.3. Western medicine

The therapeutic clinical trials contributed the largest proportion in the registrations with the number of 266 studies (Table 2). Among the tested Western medicine, 47 studies tested on antivirals including arbidol, lopinavir–ritonavir, darunavir, interferon, ribavirin, and danoprevir. Apart from these antivirals in China, five RCTs registered for remdesivir, including two phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study for mild/moderate and severe patients, two phase III RCTs comparing different duration with standard therapy, and one phase II multicenter, adaptive, randomized blinded controlled trial. Other trials tested antivirals not marketed in China including fapilavir, xofluza, azvudine, triazavirin, and ASC09F. As for the latest status, the two RCTs of remdesivir in China were suspended or terminated due to the lack of participants.

Table 2.

Categories of Western Medicine and Chinese Medicine in the Registered Studies

| Intervention | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western medicine | Antiviral drugs | 47 | 17.7 |

| Stem cell and cord blood therapy | 27 | 10.2 | |

| Chloroquine and derivatives | 22 | 8.3 | |

| Immunology and monoclonal antibodies | 15 | 5.6 | |

| Convalescent plasma | 8 | 3.0 | |

| Inhalation therapy | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Glucocorticoids | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Psychological therapy | 4 | 1.5 | |

| Vitamins | 3 | 1.1 | |

| ECMO | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Others | 36 | 13.5 | |

| Chinese medicine | CM with no details | 46 | 17.3 |

| Patent herbal drugs | 17 | 6.4 | |

| Herbal injections | 10 | 3.8 | |

| Non-pharmaceutical intervention | 9 | 3.4 | |

| Herbal decoctions | 6 | 2.3 | |

| Multiple Chinese medicine therapy | 2 | 0.8 |

ECMO, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Other clinical studies for Western treatments included 27 for stem cell and cord blood, 22 for chloroquine and derivatives, 15 for immunological agents and monoclonal antibodies, 8 for convalescent plasma therapy, 6 for inhalation therapy of oxygen, nitric oxide, and hydrogen-oxygen, 6 for glucocorticoids, 4 for psychological therapy, 3 for vitamins, and 3 for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

There were 8 studies for COVID-19 prevention testing Western medicine, such as arbidol, interferon spray, hydroxychloroquine and mask for doctors during gastroscopy. These studies had not started recruitment according to the registrations.

3.4. Traditional Chinese medicine and their rationale

The secondary category of interventions was Chinese medicine and integrated therapies of multiple drugs and non-pharmaceutical interventions. There were 46 studies using Chinese medicines without detailed information, and one tested Chinese medicine granule for people with common cold. The involved Chinese medicines, compositions, and rationale in 34 studies are presented in Table 3. Fourteen Chinese medicines had evidence on COVID-19 or related diseases (acute upper respiratory tract infections, acute bronchitis, pneumonia, influenza) or symptoms in silico, in vitro, in vivo and in human level such as expert consensus statement, RCTs, systematic reviews, and overview. The non-pharmaceutical Chinese therapies included acupuncture, massage (tuina) in children, moxibustion, emotional therapy, different styles of Qigong such as Dao-yin, acupressure combined with Liuzijue Qigong, Baduanjin, integrative exercises for lung function recovery, fitness Qigong Yangfei prescription, and Guixi Tiao Fei Gong method. There was only one study registered for each non-pharmaceutical Chinese therapies. Moxibustion (a traditional used therapy) was recommended by the Guidance on acupuncture for COVID-19 by China Association of Acupuncture-Moxibustion, and acupuncture should be combined with Western medicine.21 The functional recovery of integrated therapy such as Taichi, Baduanjin, Wuqinxi exercise, Liuzijue qigong, Yijinjing were recommended by the research team from Shanghai University of Chinese Medicine.22

Table 3.

Compositions and Rationale for Tested Chinese Herbal Medicine

| Category | Medicine name (trial numbers) | Compositions | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patent drugs | Lianhua Qingwen granule/capsules (2) | Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), Ephedrae Herba (Mahuang), Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Kuxingren), Isatidis Radix (Banlangen), Dryopteridis Crassirhizomatis Rhizoma (Mianmaguanzhong), Houttuyniae Herba (Yuxingcao), Pogostemonis Herba (Guanghuoxiang), Rhei Radix et Rhizoma (Dahuang), Rhodiolae Crenulatae Radix et Rhizoma (Hongjingtian), and Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Gancao), along with l-Menthol (Bohenao) and a traditional Chinese mineral, Gypsum Fibrosum (Shigao) | In vitro: Significantly inhibits the SARS-COV-2 replication, affects virus morphology and exerts anti-inflammatory activity in vitro. These findings indicate that LH protects against the virus attack, making its use a novel strategy for controlling the COVID-19 disease.8 |

| Jinyebaidu granule (1) | Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), Isatidis Folium (Daqingye), Taraxaci Herba (Pugongying), Houttuyniae Herba (Yuxingcao) | NA | |

| Kangbingdu granule (1) | Isatidis Radix (Banlangen), Lonicerae Japonicae Caulis (Rendongteng), Sophorae Tonkinensis Radix et Rhizoma (Shandougen), Iridis Tectori Rhizoma (Chuanshegan), Houttuyniae Herba (Yuxingcao), Paridis Rhizoma (Chonglou), Cyrtomium fortune J. Sm. (Guanzhong), Paeoniae Radix Alba (Baizhi), Artemisiae Annuae Herba (Qinghao), along with Sucrose | In silico: The active compounds in Kangbingdu Keli can interact with angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2) to target PTGS2, HSP90AB1, and PTGS1 to regulate multiple signal pathways, thereby exerting therapeutic effects on COVID-19.9 | |

| Xiao’er Huatan Zhike granule (1) | Flow extract of Radix platycodonis (Jiegeng), Flow extract of Mori Cortex (Sangbaipi), Tinctura Ipecacuanhae (Tugending), Ephedrine Hydrochloride, along with Citric Acid, Sodium Citrate, Sucrose and essence. | NA | |

| Jingyin granule (1) | Schizonepetae Herba (Jingjie), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), Arctii Fructus (Niubangzi), Isatidis Folium (Daqingye), Ilicis Chinensis Folium (Sijiqing) | NA | |

| Huaier granule (1) | Aqueous extract of Trametes robiniophila Murr | NA | |

| Ganke Shuangqing capsule (1) | Baicalin (Huangqigan), Andrographolide (Chuanxinlianneizhi) | SR: The whole effectiveness of Ganke Shuangqing Capsules for acute upper respiratory tract infections was better than ribavirin, However, this conclusion needs more high quality study to confirm.10 | |

| Keqing capsule (1) | Reineckia Carnea (Jixiangcao), Papaveris Pericarpium (Yingsuqiao), Ardisiae Japonicae Herba (Aidicha), Saxifraga stolonifera (Huercao), Eriobotryae Folium (Pipaye), Mori Cortex (Sangbaipi) | In vivo: As the first-line drugs for novel coronavirus pneumonia, Keqing capsules and Kesuting syrups have significant therapeutic effect on the mouse model combining disease and syndrome of human coronavirus pneumonia with cold-dampness pestilence attacking lung, and the mechanism may be related to regulating immune function and reducing cytokine storm.11 | |

| Kesuting syrup (1) | Eriobotryae Folium (Pipaye), Ephedrae Herba (Mahuang), Papaveris Pericarpium (Yingsuqiao), Radix platycodonis (Jiegeng), Mori Cortex (Sangbaipi), Reineckia Carnea (Jixiangcao), Disporum Cantoniense et Rhizoma (Baiweishen), Saxifraga stolonifera (Huercao), Polygonati Rhizoma (Huangjing) | As above | |

| Shuanghuanglian liquid (2) | Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), Scutellariae Radix (Huangqin) | In vitro: Shuanghuanglian liquid may have the antiviral activity against the H5N1 virus infection by inhibiting viral replication and alleviating lung injury.12 | |

| Ba-Bao-Dan (2) | Bovis Calculus Artifactus (Rengong Niuhuang), Snake bile (Shedan), Saigae Tataricae Cornu (Lingyangjiao), Margarita (Zhenzhu), Notoginseng Radix Et Rhizoma (Sanqi), Moschus (Shexiang) | NA | |

| Compound Houttuyniae Herba (2) | Houttuyniae Herba (Yuxingcao), Scutellariae Radix (Huangqin), Isatidis Radix (Banlangen), Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua) | NA | |

| Liu-Shen-Wan (1) | Bovis Calculus Artifactus (Rengong Niuhuang), Moschus (Shexiang), Bufonis Venenum (Chansu), Realgar (Xionghuang), Borneolum (Tianranbingpian), Margarita (Zhenzhu) | NA | |

| Fuzheng Huayu Tablet (1) | Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Danshen), Persicae Semen (Taoren), Schisandrae Chinensis Fructus (Wuweizi), Cordyceps (Dongchongxiacao), Gynostemma pentaphyllum (Jiaogulan), Pini Pollen (Songhuafen) | NA | |

| T89 (1) | Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Danshen), Notoginseng Radix Et Rhizoma (Sanqi) | Overview: Current SRs suggested potential benefits of CDDP for the treatment of CHD. However, high-quality evidence is warranted to support the application of CDDP in treating CHD. 13 (T89 has a similar composition with CDDP and the trial on COVID-19 was aiming to improve oxygen saturation and clinical symptoms) |

|

| Injections | Xuebijing Injection (2) | Carthami Flos (Honghua), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), Chuanxiong Rhizoma (Chuanxiong), Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), and Salviae Miltiorrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Danshen) | RCT: Significant improvement in the primary endpoint of the pneumonia severity index as well as significant improvement in the secondary clinical outcomes of mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation and duration of ICU stay.14 |

| Tanreqing injection (1) | Scutellariae Radix (Huangqin), Pulvis Fellis Ursi (Xiongdanfen), Saigae Tataricae Cornu (Lingyangjiao), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao), along with Propylene Glycol | SR: Potentially beneficial effect in improving effective rates, reducing the time to resolution of fever, cough, crackles and absorption of shadows on X-ray on acute bronchitis disease.15 | |

| Reduning Injection (1) | Artemisiae Annuae Herba (Qinghao), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Jinyinhua), Gardeniae Fructus (Zhizi), along with Polysorbate 80 | RCT: The effect of RDNI was not worse than oseltamivir on the alleviation of influenza symptoms. RDNI was well tolerated, with no serious adverse events noted during the study period.16 | |

| Xiyanping injection (4) | Andrographolides sulfonate(Chuanxinlian) | Expert consensus statement: Non-severe patients without high risk factors for severe influenza can shorten the duration of fever, headache and cough; patients with severe or high risk factors for severe influenza can be given anti-influenza virus medication as soon as possible, and combined with Xiyanping injection can promote fever, Cough, sore throat, muscle soreness, headache and other symptoms; influenza high fever (armpit temperature>39 °C) is recommended to use Xiyanping injection combined with neuraminidase inhibitor treatment.17 | |

| Shenqi Fuzheng Injection (1) | Codonopsis Radix (Dangshen), Astragali Radix (Huangqi), | NA | |

| Shenfu injection (1) | Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma Rubra (Hongshen), Aconiti Lateralis Radix Praeparata (Fuzi) | RCT: The application of Shenfu injection exhibited a positive and effective effect on removing the inflammation media during the treatment of elderly severe pneumonia.18 | |

| Decoctions | Jinyinhua decoction/honeysuckle oral liquid (2) | Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (jinyinhua) | In vivo and in vitro: MIR2911, a honeysuckle (HS)-encoded atypical microRNA, can directly target various Influenza A viruses and may represent a novel type of natural product that effectively suppresses viral infection.19 |

| Ma-Xing-Shi-Gan-Tang and Sheng-Jiang-San (1) | Ephedrae Herba (Mahuang), Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Kuxingren), Glycyrrhizae Radix Et Rhizoma (Gancao), and a traditional Chinese mineral, Gypsum Fibrosum (Shigao); Bombyx Batryticatus (Jiangcan), Cicadae Periostracum (Chantui), Curcumae Longae Rhizoma (Jianghuang), Rhei Radix Et Rhizoma (Dahuang) | RCT: Oseltamivir and maxingshigan-yinqiaosan, alone and in combination, reduced time to fever resolution in patients with H1N1 influenza virus infection. These data suggest that maxingshigan-yinqiaosan may be used as an alternative treatment of H1N1 influenza virus infection.20 | |

| Shenling Baizhu Powder (1) | Lablab Semen Album (Baibiandou), Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma (Baizhu), Poria (Fuling), Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Gancao), Radix Platycodonis (Jiegeng), Nelumbinis Semen(Lianzi), Ginseng Radix Et Rhizoma (Renshen), Amomi Fructus (Sharen), Dioscoreae Rhizoma (Shanyao), Coicis Semen (Yiyiren) | NA | |

| Yinhu Qingwen decoction/granule (1) | Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (jinyinhua), Polygoni Cuspidate Rhizome et Radix (Huzhang), Schizonepetae herba (Jingjie), Epimedii Folium (Yinyanghuo), etc. (No more information available) | NA | |

| Qing-Wen Bai-Du-Yin formula granules (1) | Rehmanniae Radix (Shengdihuang), Coptidis Rhizoma (Huanglian), Gardeniae Fructus (Zhizi), Radix Platycodonis (Jiegeng), Scutellariae Radix (Huangqin), Anemarrhenae Rhizoma (Zhimu), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), Scrophulariae Radix (Xuanshen), Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqaio), Lophatheri Herba (Zhuye), Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma Praeparata Cum Melle (Zhigancao), Moutan Cortex (Mudanpi), and along with a traditional Chinese mineral, Gypsum Fibrosum (Shengshigao) | NA | |

| Chaihu Qingwen decoction (Kangguan No. 1 Recipe)(1) (for suspected COVID-19 cases, ordinary patients, and the prevention for people exposed to patients) | Bupleuri Radix (Chaihu), Scutellariae Radix (Huangqin), Pinelliae Rhizoma Praeparatum (Fabanxia), Cinnamomi Ramulus (Guizhi), Magnoliae Officinalis Flos (Houpohua), Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Xingren), Asteris Radix et Rhizoma (Ziwan), Isatidis Folium (Daqingye), Isatidis Radix (Banlangen), Taraxaci Herba (Pugongying), Lonicerae Japonicae Flos (Yinhua), Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao), Chrysanthemi Flos (Juhua), Lonicerae Japonicae Caulis (Rendongteng), Phragmitis Rhizoma (Lugen), Imperatae Rhizoma (Baimaogen), Viticis Fructus (Manjingzi), | NA | |

| Qingfei Jiebiao decoction (Kangguan No. 2 Recipe)(1) (for COVID-19 patients with accumulation of pathogenic heat in the lung pattern) | Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Kuxingren), Platycodonis Radix (Jiegeng), Pheretima (Dilong), Poria (Fuling), Saposhnikoviae Radix (Fangfeng), Ephedrae Herba Praeparata Cum Melle (Mimahuang), Setariae Fructus Germinatus (Guya), Peucedani Radix (Qianhu), Trichosanthis Pericarpium (Gualoupi), Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Gancao), Chrysanthemi Flos (Juhua), Fructus Forsythiae (Lianqiao), Fritillariae Thunbergii Bulbus (Zhebeimu), Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium (Chenpi), Mori Folium (Sangye), Medicated Leaven (Liushenqu), Hordei Fructus Germinatus (Maiya), Cynanchi Stauntonii Rhizoma et Radix (Baiqian) | NA | |

| Chibai Rougan decoction (Kangguan No. 3 Recipe) (1) (for COVID-19 patients with depressed liver-gallbladder heat pattern) | Poria (Fuling), Coicis Semen (Yiyiren), Corydalis Rhizoma (Yanhusuo), Paeoniae Radix Alba (Baishao), Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Chishao), Atractylodis Macrocephalae Rhizoma (Baizhu), Artemisiae Scopariae Herba (Yinchen), Platycladi Semen (Baiziren), Sepiae Endoconcha (Haipiaoxiao), Pseudostellariae Radix (Taizishen), Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma (Gancao), Amomi Fructus (Sharen), Curcumae Radix (Yujin), Angelicae Sinensis Radix (Danggui), Imperatae Rhizoma (Baimaogen), Pyrrosiae Folium (Shiwei), Galli Gigerii Endothelium Corneum (Jineijin), Puerariae Lobatae Radix (Gegen), Astragali Radix (Huangqi) | NA | |

| Self-made decoction(1) (for ordinary COVID-19 patients) | Atractylodis Rhizoma (Cangzhu), Magnoliae Officinalis Cortex (Houpo), Pogostemonis Herba (Huoxiang), (Caoguo), Ephedrae Herba (Mahuang), Cicadae Periostracum (Chantui), Rhizoma Zingiberis Recens (Shengjiang), Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Xingren), Polygoni Cuspidate Rhizome et Radix (Huzhang) | NA | |

| Self-made decoction(1) (for severe COVID-19 patients) | Ephedrae Herba (Mahung), Armeniacae Semen Amarum (Xingren), Eriobotryae Folium (Pipaye), Descurainae Semen Lepidii Semen (Tinglizi), Sinapis Semen (Baijiezi), Raphani Semen (Laifeuzi), Arecae Semen (Binglang), Rhei Radix et Rhizoma (Dahuang), Polygoni Cuspidate Rhizome et Radix (Huzhang), along with a traditional Chinese mineral, Gypsum Fibrosum (Shigao) | NA |

SR, systematic review and/or meta-analysis; NA, not available; CDDP, Compound Danshen dripping pill; CHD, coronary heart disease; RDNI, Reduning injection.

Except for trials on therapeutic effect, Chinese medicine was also tested for the prevention and rehabilitation of coronavirus patients. For prevention, the tested herbal therapies included Jinhao Jiere granule, Gubiao Jiedu Ling, Jinye Baidu granule, Kangbingdu oral liquid, Compound Houttuyniae Herba, and moxibustion. For rehabilitation, Taichi was tested for pulmonary function and quality of life in COVID-19 patients at convalescent stage, and integrated exercises for lung function recovery were tested in survivors of COVID-19. Besides, emotional therapy of Chinese medicine was tested for COVID-19 patients and nurses.

3.5. Outcomes of the registered studies

In Table 4, only 17 RCTs, 2 controlled clinical trials, and 12 observational studies used mortality as a primary outcome. Other clinical important outcomes such as exacerbation rate/time and length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay were also seldom used as primary outcomes. Symptoms and signs, viral nucleic acid/viral loads, and imaging examinations (chest CT, X radiograph, etc.) were the most used in the primary outcomes. Similarly, symptoms and signs, common laboratory tests (blood, urine routine, biochemical, etc.), and viral nucleic acid/viral loads were the most used in the secondary outcomes, and mortality and safety outcomes were also frequently mentioned in secondary outcomes.

Table 4.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes Measured in the Registered studies on Therapeutic Effect Evaluation

| Outcomes | No. of studies indicated as primary outcomes (%) | No. of studies indicated as secondary outcomes (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 31 (11.7) | 67 (25.2) |

| Exacerbation rate/time | 26 (9.8) | 62 (23.3) |

| Length of stay in ICU | 2 (0.8) | 25 (9.4) |

| Length of hospital stay | 20 (7.5) | 58 (21.8) |

| Cure rate | 23 (8.7) | 17 (6.4) |

| Discharge rate | 6 (2.3) | 4 (1.5) |

| Lung function | 28 (10.5) | 30 (11.3) |

| Mechanical ventilation and oxygen inhalation time/rate | 12 (4.5) | 52 (19.6) |

| Imaging examinations (chest CT, X radiograph, etc.) | 47 (17.7) | 43 (16.2) |

| Oxygenation indicator | 29 (10.9) | 28 (10.5) |

| Symptoms and signs | 105 (39.5) | 125 (47.0) |

| Health status/mental state/quality of life | 9 (3.4) | 18 (6.8) |

| Viral nucleic acid/viral loads | 76 (28.6) | 86 (32.3) |

| Common laboratory tests (blood, urine routine, biochemicals, etc.) | 40 (15.0) | 109 (41.0) |

| Safety (adverse events/adverse drug reactions, etc.) | 18 (6.8) | 67 (25.2) |

| Complications | 4 (1.5) | 10 (3.8) |

| TCM Syndrome score | 11 (4.1) | 12 (4.5) |

| Other outcomes | 12 (4.5) | 17 (6.4) |

CT, computerized tomography; ICU, Intensive care unit; TCM, Traditional Chinese Medicine; Viral loads, changes of real-time reverse-transcriptase-polymerase-chain-reaction testing.

4. Discussion

This study systematically reviewed available registered studies for COVID-19 with the analyses of their distributions and characteristics. Three hundred and ninety-three studies were registered in eight registries, aiming at the prevention, treatment, diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19. Majority of the studies were randomized trials, followed by observational studies testing different interventions such as antiviral drugs, Chinese medicine, and integrated therapies. Except for 50 studies, clinical important outcomes such as mortality and exacerbation rate/time were not set as primary outcomes in majority trials. One hundred and seventy-nine studies had not started recruiting and would hardly be able to carry on in China due to insufficient patients.

As a new communicable disease, direct evidence for the prevention of COVID-19 is not available. We found insufficient evidence to support the rationale for tested Western medicines, while based on historical records and human evidence of SARS and H1N1 influenza prevention, Chinese herbal formula is considered as an alternative approach for prevention of COVID-19 in high-risk population.23 The therapeutic clinical studies made up the largest proportion of the registrations. Antivirals, the most promising category of Western medicine, accounted for 17.7% out of the therapeutic studies. In terms of Chinese medicines, 14 had clinical or laboratory evidence, showing the potential therapeutic effects on COVID-19 patients.

Though two months have passed after the retrieving date (March 3rd) of our study, few trials released the results. Flaws in study design, such as the setting of the control and outcomes, and the lack of coordination were discovered from the registrations. Even in an outbreak, investigational products should be evaluated scientifically and ethically.24 Do no harm is always the first rule for all human studies. Methodologically, double-blind randomized, placebo controlled trials are considered to be the gold standard for therapeutic clinical trials.25 However, considering the emergency and the practical issues of ethics and informed consent, the implementation of RCT faces more challenges. In the context of COVID-19 pandemic, the control interventions should be supportive care.

As statistics shows, the mortality of COVID-19 was 4.3% in Wuhan, China, indicating severe life-threatening disease.26 New studies on clinical characteristics of COVID-19 also reported outcomes on exacerbation, such as the median time from first symptom to dyspnea, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), transfer to the ICU due to complications and death of multiple organ failure, 26, 27 and other symptoms and laboratory findings for example neutrophilia, organ and coagulation dysfunction, which were potential risk factors for ARDS and elevated d-dimer as risk factors for mortality.28, 29 On the contrary, clinical important outcomes such as mortality and exacerbation were only used as primary outcomes in 21.5% analyzed registrations, and the observational measures in clinical practice such as symptoms, signs, common laboratory tests and viral nucleic acid/viral load were used more frequently. Additionally, the most used primary and secondary outcomes were similar and clear measurements and time points were seldom available. The design of more than three primary outcomes in one trial may bring problems in the interpretation of research results.6

Although the number of registered trials is increasing, only carefully conducted trials can show which measures work.30 Without a coordination of the research teams in the whole country, potential participants could be scattered in numerous small studies, resulting in less powerful results or incomplete trials. There were only 3 international and 36 domestic collaboration studies, suggesting a low level of cooperation. The registrations showed that nearly half of the studies had not started recruiting by March 3rd, while the new cases in China were sharply reducing. Besides, a few of the sponsors had withdrawn their studies due to lack of patients. In fact, we could learn from the experience on study design of Ebola virus disease according to WHO documents.25, 31 For example, the adaptive trial designs were used in the Ebola epidemic, it has the capacity to yield meaningful and interpretable data quickly, while more complex to coordinate among different sites. The key points of study design in these documents may also helpful for the design and implementation of COVID-19 clinical trials.

There are several limitations in our research. First, the registrations provide limited information on the trials, and our analysis is based on the registered information but not the full protocols. Second, the required information of the registrations are not unique across different registries, and the information could be revised by sponsors after the search and analysis, so the results may not include the whole registered information of the COVID-19 studies. Third, the number of registered trials is escalating quickly, as for April 29th, 632 and 997 studies were registered in ChiCTR and Clinicaltrials.gov, it is hard to trace the details of these information up-to-date, and our study mainly reflect the overview of the registered clinical studies in the early time of COVID-19 outbreak. Besides, the retrieving date was before the announcement of the global pandemic, so the studies were mainly from China.

More international collaborations, rapid data sharing, and strengthened coordination are needed in the searching for effective therapy. As WHO suggested, enhancing global coordination of all relevant stakeholders, a clear and transparent global research and innovation priority setting and common platforms for standardized process are needed in the research during the outbreak.32 As reported, WHO and partners are launching SOLIDARITY trial and aims to generate robust data for the most effective treatment for COVID-19.3 Furthermore, rapid data sharing is warranted once they are adequately quality controlled for release.33 To response the outbreak of COVID-19, a quick upload of data is recommended when registered trials initiated so for immediate analysis and inform upcoming trials. In addition, the coordination of the trials are urgently needed. More rigorous regulations by the National Health Commission in China have been delivered for the clinical studies on COVID-19 recently, aim to strengthen overall coordination, promote data integration, and improve research efficiency.34 With the statistics of registered information, we will trace the trials for the update status regularly. Further research could be conducted to investigate the impact factors of a successful trial in the emergency of public events, and summarize valuable experience for the protocols of unexpected emergency events.

In conclusion, from January 23rd to March 3rd 2020, 393 studies were registered for the prevention, treatment, diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19. The limitations of design, delayed recruitment, and insufficient numbers of new cases in China make studies difficult to complete. International collaborations are important to achieve efficient research on global pandemics, and robust and rapid data sharing is urgently needed. Research protocols for public health emergency will be warranted and priority trials could be defined in shorter time, avoiding the waste of resources and duplication of research efforts.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Dr. Junchao Chen for the retrieval of WHO Guidance and Dr. Fei Dong for her searching suggestions.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MY, YZ and JPL. Methodology: MY and JPL. Software: MY and YXS. Validation: ZYT, MX and YJ. Formal analysis: MY and YXS. Investigation: MX, YJ, Yao Zhang, YYZ, YXS, ZYT, XYJ and QBJ. Resources: YXS. Data curation: MY and YXS. Writing – original draft: CLL, ZYT and MY. Writing – review & editing: YZ, JPL and MW. Visualization: MY and YXS. Supervision: JPL. Project administration: JPL. Funding acquisition: JPL and YZ. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81830115) “Key techniques and outcome research for therapeutic effect of traditional Chinese medicine as complex intervention based on holistic system and pattern differentiation & prescription”, China.

Dr. Ying Zhang was partially supported by the Emergency Program for Serious Infectious Diseases (No. 2020-yjgg-14), School of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing University of Chinese Medicine.

Ethical statement

This research did not involve any human or animal experiment.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article.

The included trials were published on the open access website and databases.

Footnotes

Supplementary figures associated with this article can be found in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.imr.2020.100426.

Appendix I. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Figure S1.

Provincial location of participant recruitment from studies in mainland China.

Supplementary Figure S2.

Applicant's institutions of the registered studies.

References

- 1.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q., Guan X., Wu P., Wang X., Zhou L., Tong Y. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jan 29] N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) events as they happen. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/events-as-they-happen. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Worldometer . 2020. Coronavirus update (live) Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus. Accessed April 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.2020. The State Council, the People's Republic of China Premier Li Keqiang presided over a meeting of the Central Leading Group for New Coronary Pneumonia Epidemic Situation, deployed further classification, effective prevention and control, required optimization of diagnosis and treatment, and accelerated scientific research on drug control. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/premier/2020-02/13/content_5478410.htm. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei X., Zhao M., Zhao C., Zhang X., Qiu R., Lin Y. The global registry of COVID-19 clinical trials: indicating the design of traditional Chinese medicine clinical trials. TMR Mod Herb Med. 2020 doi: 10.12032/TMRmhm202003068. online. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . 2020. Prevention and control of new coronavirus pneumonia. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/xxgzbd/gzbd_index.shtml. Accessed March 26, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li R., Hou Y., Huang J., Pan W., Ma Q., Shi Y. Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 20] Pharmacol Res. 2020:104761. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yao Y., He Z., Liu X., He Y., Lei Y., Zhang S. Potential material basis of Kangbingdu Keli for the treatment of coronavirus pneumonia 2019 (COVID-19) based on network pharmacology and molecular docking technology. Chinese Trad Herb Drugs. 2020;51:1386–1396. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin J., Lv J., Wang Z., Xie Y., Sun M. Effectiveness and safety of Ganke Shuangqing capsule for acute upper respiratory tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Chinese Med. 2020;15:24–29. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao R., Sun J., Shi Y., Bao L., Geng Z., Guo S. Intervening effect of promoting lung and resolving phlegm method on a mouse model combining disease and syndrome of human coronavirus pneumonia with cold-dampness pestilence attacking lung. Chinese J Exp Trad Med Form. 2020:1–7. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang Y., Wang Z., Huo C., Guo X., Yang G., Wang M. Antiviral effects of Shuanghuanglian injection powder against influenza A virus H5N1 in vitro and in vivo. Microb Pathog. 2018;121:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo J., Song W., Yang G., Xu H., Chen K. Compound Danshen (Salvia miltiorrhiza) dripping pill for coronary heart disease: an overview of systematic reviews. Am J Chin Med. 2015;43:25–43. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X15500020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song Y., Yao C., Yao Y., Han H., Zhao X., Yu K. XueBiJing injection versus placebo for critically ill patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2019;47:e735–e743. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang P., Liao X., Xie Y.M., Chai Y., Li L.H. Tanreqing injection for acute bronchitis disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Complement Ther Med. 2016;25:143–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Y., Mu W., Xiao W., Wei B., Wang L., Liu X. Efficacy and safety of Re-Du-Ning injection in the treatment of seasonal influenza: results from a randomized, double-blinded, multicenter, oseltamivir-controlled trial. Oncotarget. 2017;8:55176–55186. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Z., Zhang H., Xie Y., Miao Q., Sun Z., Wang R. Expert consensus statement on Xiyanping Injection for respiratory system infectious diseases in clinical practice (adults) China J Chinese Mater Med. 2019;44:5282–5286. doi: 10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20191105.502. [In Chinese, English abstract] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lv S.J., Lai D.P., Wei X., Yan Q., Xia J.M. The protective effect of Shenfu injection against elderly severe pneumonia. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2017;43:711–715. doi: 10.1007/s00068-016-0713-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou Z., Li X., Liu J., Dong L., Chen Q., Liu J. Honeysuckle-encoded atypical microRNA2911 directly targets influenza A viruses. Cell Res. 2015;25:39–49. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C., Cao B., Liu Q., Zou Z., Liang Z., Gu L. Oseltamivir compared with the Chinese traditional therapy maxingshigan-yinqiaosan in the treatment of H1N1 influenza: a randomized trial [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jan 3;156(1 Pt 1):71] Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:217–225. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-4-201108160-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.China Association of Acupuncture-Moxibustion . 2020. Guidance on acupuncture intervention for COVID-19 by China Association of Acupuncture-Moxibustion. Available from: http://www.caam.cn/article/2183. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu X., Liu L., Lu Y., Feng L., Zhao F., Wu X. Guidance and suggestions on rehabilitation training of integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine for functional recovery of patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Shanghai J Trad Chinese Med. 2020;54:9–13. [In Chinese, English abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luo H., Tang Q.L., Shang Y.X., Liang S.B., Yang M., Robinson N. Can Chinese medicine be used for prevention of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19)?. A review of historical classics, research evidence and current prevention programs [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 17] Chin J Integr Med. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11655-020-3192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fauci A.S., Lane H.C., Redfield R.R. Covid-19-navigating the uncharted [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 28] N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2002387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . 2014. Ethical issues related to study design for trials on therapeutics for Ebola virus disease. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/ethical-evd-therapeutics/en. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 7] JAMA. 2020:e201585. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang D., Lin M., Wei L., Xie L., Zhu G., Dela Cruz C.S. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Feb 7] JAMA. 2020;323:1092–1093. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 13] JAMA Intern Med. 2020:e200994. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 11] [published correction appears in Lancet] Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maxmen A. Slew of trials launch to test coronavirus treatments in China. Nature. 2020;578:347–348. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00444-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization . 2018. Consultation on clinical trial design for ebola virus disease. Available from: https://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/ebola/consultation-clinical-trial-design-ebola/en. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization . 2020. 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): strategic preparedness and response plan for the new coronavirus. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/strategic-preparedness-and-response-plan-for-the-new-coronavirus. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization . 2016. Guidance for managing ethical issues in infectious disease outbreaks. Available from: https://www.who.int/ethics/publications/infectious-disease-outbreaks/en. Accessed March 26, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ministry of Science, Technology of the People's Republic of China . 2020. Letter of the joint prevention and control mechanism of the State Council on notice on standardizing medical institutions to carry out clinical research on new coronavirus pneumonia drug treatment. Available from: http://www.most.gov.cn/tztg/202004/t20200403_152882.htm. Accessed April 6, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this article.

The included trials were published on the open access website and databases.