The Bay Area Orders, which broke the floodgates on mandatory sheltering-in-place as a strategy for mitigating the spread of Covid-19 in the USA, originated in post-9/11 public health preparedness plans and long-standing relationships between public health scientists and lawyers.1 The powerful combination of public health science and law has prompted more than its fair share of legal and ethical controversy. From compulsory vaccination orders to sanitary cordons, from “Big Gulp bans” to prohibitions on the sale of tobacco products at pharmacies, public health laws have often put judges in the position of assessing the reasonableness of restrictions on individual and economic liberty. The standards of review judges have developed to guide this task, require political leaders to articulate not only the purpose of their actions but also the fit between their ends and the means they have adopted. Assessing the means-ends fit usually boils down to a discussion of scientific evidence and guidelines.

Although the law governing public health emergency orders is surprisingly unsettled, public health law experts widely agree that an assessment of the “necessity, effectiveness, and scientific rationale” for intrusive measures is a key feature of judicial review.2 In a crisis like the Covid-19 pandemic, the role of judges is first and foremost to adjudicate urgent requests for temporary restraining orders and preliminary injunctions. This means that judges hearing challenges to bans on gatherings, orders to stay at home except for essential work and needs, orders to close gun shops, orders to halt abortion care, and detention of civil immigration detainees in crowded and unsanitary conditions are issuing orders based largely on the parties’ pleadings alone. There is little time—yet—for the discovery, expert testimony, or amicus briefs from professional groups that typically inform assessments of science by judges.

This essay examines the role of public health scientific guidelines in the adjudication of legal challenges to mandatory orders adopted as part of the community mitigation strategy for the Covid-19 pandemic. This examination of judicial precedents arising out of emergency communicable disease control measures—prior to and during the Covid-19 pandemic—reveals that judges rely heavily on guidelines from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC). This may be cause for concern, given that federal guidelines for Covid-19 have been slow to respond to the reality of Covid-19’s rapid spread and rising death toll in the US.3 The White House has issued guidelines independently of CDC and both sets of guidelines have fallen short of endorsing the orders mandating all residents to stay at home that the majority of states and many local governments have imposed. The essay concludes by arguing that because guidelines issued by international and federal agencies play an important role in adjudication of conflicts between emergency communicable disease control orders and civil liberties, they should be held to a higher standard of transparency and accountability than their voluntary nature might otherwise suggest.

The Community Mitigation Strategy for Covid-19: Government Powers and Duties and Individual Rights Constraints

To mitigate the spread of Covid-19, federal, state, and local officials have exercised broad powers available to them under public health statutes and emergency declarations to close businesses and restrict the movement of individuals outside their homes.4 A widely cited report assumes that multi-layered non-pharmaceutical interventions, also known as community mitigation measures, will be necessary for at least 3 months to reduce peak impacts on health systems.5 While we wait for a safe and effective vaccine, some degree of community mitigation may be needed on an intermittent basis—in some places at some times—for the year or longer it takes to develop and widely distribute a safe and effective vaccine.6

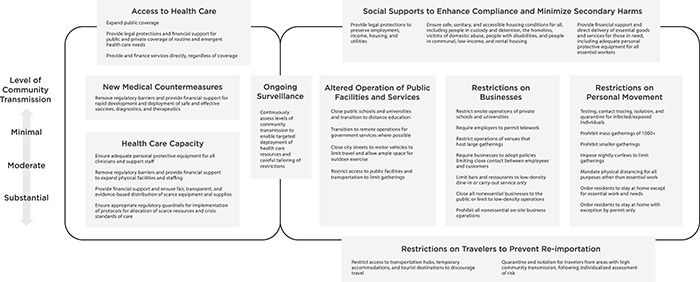

Past experience shows that community mitigation—through a combination of government supports, protections, and restrictions—is an important strategy to slow the spread of viral epidemics in addition to efforts to increase access to and the capacity of the health care system and the development and deployment of effective medical countermeasures such as vaccines and antivirals (see Figure 1). Early evidence suggests that spread of the virus by people whose infections are not detected may play a particularly important role in Covid-19,7 potentially making more targeted containment strategies—measures to test and isolate individuals known to be infected and trace and quarantine their known contacts—insufficient in the absence of broader community mitigation measures to reduce out-of-household contacts among the general population.

Figure 1.

Governmental powers and responsibilities in pandemic response. CDC recommendations define levels of community transmission as follows: None to Minimal: Evidence of isolated cases or limited community transmission, case investigations underway, no evidence of exposure in large communal setting, e.g., healthcare facility, school, mass gathering. Minimal to Moderate: Widespread and/or sustained transmission with high likelihood or confirmed exposure within communal settings with potential for rapid increase in suspected cases. Substantial: Large scale community transmission, healthcare staffing significantly impacted, multiple cases within communal settings like healthcare facilities, schools, mass gatherings etc. US Centers for Disease Control, Implementation of Mitigation Strategies for Communities with Local COVID-19 Transmission (Mar. 12, 2020), available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf (last visited Apr. 4, 2020). Figure adapted in part from Lawrence O. Gostin and Lindsay F. Wiley, JAMA (forthcoming April 2020, figure included in online edition only).

Due to the unprecedented nature of the Covid-19 crisis, the intrusive measures currently in force across many US jurisdictions are largely untested. Benefits are anticipated based on modeling and planning exercises developed in preparation for a novel influenza pandemic,8 and limited studies of measures implemented in mainland China, Hong Kong, and parts of Europe in response to Covid-19.9 Ongoing research and surveillance are needed to assess these measures in real time. Legal authority to impose restrictions on businesses, individuals, and travel may be inferred from the broad public health powers available to state governments and specific delegations of emergency powers to governors and mayors, but these measures are subject to individual rights constraints. By the end of March 2020, lawsuits challenging gathering bans and stay at home orders were pending in the New Hampshire state court system and the Eastern District of New York.10 Suits requesting injunctive relief for people in criminal custody and immigrant civil detention were pending in at least three federal jurisdictions. Several suits on behalf of legal practices, firearms retailers, abortion service providers were also pending in multiple jurisdictions. More court challenges are likely to come as restrictions remain in place for weeks and months.

Government Powers to Restrict Businesses

Modeling studies and CDC guidelines for pandemic influenza suggest that closing schools and other places where people gather, as every state has done to some extent in response to Covid-19, impedes the spread of epidemics. School closures have been deployed on a limited basis by individual districts in the USA to control the spread of novel influenza viruses, with encouraging results.11 Particularly when schools and workplaces close, it may be necessary to close other places where people would otherwise congregate.

State and local restrictions on business operations under penalty of citations, fines, and loss of licenses have been ordered in nearly every US jurisdiction in response to Covid-19.12 Nearly all states and many local governments have ordered bars, restaurants, theaters, gyms, shopping malls, and other settings where people tend to gather to close or limit on-site occupancy.13 In a majority of jurisdictions, officials have gone further, closing all non-essential businesses to the public, with specified exceptions for health-care, food and agriculture, home repair, first responders, and a few other sectors deemed essential.14 Many have also prohibited elective medical procedures that are not time-sensitive, with a goal of promoting social distancing and preserving health care capacity. At the furthest end of the spectrum, several jurisdictions have prohibited all on-site operations of non-essential businesses, whether open to the public or not.15

In late April 2020, several jurisdictions indicated that they would begin to ease restrictions on businesses, but warned that limits may need to be re-tightened in response to disease trends. Even in times of low community transmission, officials indicated that restrictions on density (e.g., capping occupancy at 25 per cent of what is permitted under fire safety codes) and interactions among employees and customers (e.g., limiting non-essential retail to curbside pick-up) may be in place for long durations.

Public health authority to regulate businesses under the banner of public health is vast, but constitutional requirements of due process and equal protection of the law bar these powers from being wielded in an arbitrary or capricious manner. In addition, heightened standards of review may apply to restrictions that implicate fundamental rights, such as the right to bear arms or access family planning services. Businesses affected by closures could argue that mandated closure of uncrowded, but non-essential shops where customers and employees may maintain physical distance are arbitrary and not reasonably grounded in evidence about how novel coronavirus is transmitted. Though officials could defend these bans on the ground that enforcing physical distancing requirements within each facility would be too cumbersome.

The economic impacts of restrictions on businesses have already been devastating. If maintained for a long duration, the effects could be catastrophic, particularly for low-income families and small businesses. Congress, federal agencies, and state and local governments have begun to implement programs to provide financial assistance, direct delivery of food and other necessities, and legal protections from eviction and utility shut-offs. Yet more supportive measures will undoubtedly be needed as the crisis continues to unfold.

Government Powers to Restrict Individual Movement Outside the Home

Bans on large gatherings are a cornerstone of social distancing plans developed in pandemic preparedness exercises.16 In the USA, these restrictions have been tightened as evidence of novel coronavirus community transmission mounted, from bans on groups of 1000, to 250, to 50, to 10, and to groups of any size.17 At times when community transmission is low in any given area, bans could be eased, raising the limit on attendance while requiring physical distancing to be practiced by attendees. Physical distancing, particularly for long durations, can severely disrupt access to social and emotional supports. In another early court challenge to state social distancing measures, the plaintiff argued that New Hampshire’s ban on large gatherings violates their First Amendment rights to assembly and freedom of expression as well as Fourteenth Amendment right to due process.18 A suit filed in the Eastern District of New York raised a similar challenge to New York’s gathering ban and stay at home order.19

By the end of March 2020, more than half of states had gone further than banning gatherings by issuing mandates ordering residents to stay at home, with relatively broad exceptions for meeting essential needs and exercising outdoors, enforceable through criminal fines and jail time.20 While restrictions on gatherings are supported by public health emergency response guidelines, orders confining individuals to their homes are more controversial and have not been assessed as thoroughly in pandemic influenza planning. Due to logistical constraints, even mandatory orders to stay at home are dependent on widespread voluntary compliance to be successful. Compliance requires public acceptability and trust in government, which may be eroded if restrictions are harshly enforced or maintained for long durations.21

Restrictions on assembly and involuntary confinement of individuals to their homes are typically subjected to the heightened judicial scrutiny, but may be justified by balancing the curtailment of individual liberty against compelling government needs.22 In the USA, limited-duration curfews ordering individuals to stay indoors have occasionally been used by state and local officials to protect the public’s health and safety and prevent civil unrest in the event of natural disasters and other emergencies. Courts reviewing challenges to Covid-19 orders might also look to decisions upholding emergency orders restricting access to and movement within specified areas during limited periods of civil unrest. In 2005, for example, a federal appellate court upheld an emergency restricted zone to protect public safety during a meeting of the World Trade Organization in downtown Seattle.23 But long-term restrictions on activity outside the home by all residents without clear criteria or planning for when mandates might be eased or lifted are deeply problematic and require stronger justification that limited curfews or restricted zones.

Wholesale restrictions on personal movement do not allow for the individualized risk assessments courts have typically required to quarantine specific individuals infected or exposed to a communicable disease, as discussed below.24 Though some restrictions, such as requirements to maintain a distance of at least 6 feet from non-household members, might be permissible in theory in light of the best available scientific evidence regarding the spread of novel coronavirus, enforcement on the ground could be highly problematic. Even in the absence of prohibited discrimination based on race, ethnicity, or religion, a plaintiff could claim that spotty police enforcement was arbitrary and capricious. Given that some local police departments have indicated they will be pursuing more proactive enforcement, threatening large fines and the possibility of jail time, the limits of public health authority to confine individuals could be tested in the courts as the pandemic continues to impact our lives in the months and years to come.

Government Powers to Discourage or Restrict Travel

Some forms of travel restrictions and quarantine of individual travelers may be justified if they are truly necessary to protect people in areas with low-community transmission from exposure to people who have recently traveled from areas with high transmission. Guarded boundaries between or within USA states and territories would raise difficult constitutional questions.25 Bans on interstate travel imposed by state governments would have to navigate constitutional doctrines that constrain states from discriminating against non-residents26 and interfering with interstate commerce.27 The federal government has authority to close state borders pursuant to its authority to regulate interstate commerce, subject to individual rights constraints.28

Limited geographic quarantines were established by local governments in some parts of the USA more than a century ago to control bubonic plague. At least one lower federal court struck down a quarantine around a portion of San Francisco, partly on the grounds that it discriminated against Chinese Americans and partly on the grounds that it confined the infected and the uninfected together without preventing the spread of disease within the cordon.29 Reverse cordons with mandatory quarantine for all individuals permitted to enter from outside were established in some (mostly geographically isolated) local areas with low or no community transmission during the 1918 flu pandemic,30 and ad-hoc ‘shotgun quarantines’ were adopted by some localities during yellow fever outbreaks in the South beginning in the 1870s,31 but these measures do not appear to have been challenged in court.

Completely barring people from exiting an area severely affected by a disease outbreak, absent an assessment of the risks posed by individual travelers, would violate constitutional prohibitions against the deprivation of life and liberty without due process of law under almost every conceivable scenario. Barring entry into an area where community transmission is low would implicate individual rights to travel. Imposing a travelers’ quarantine, as more than a dozen states have ordered for Covid-19,32 requiring individuals entering the area to be separated from others for a reasonable incubation period, would provide a less restrictive alternative to completely closed borders.

Government Responsibilities for Supportive Measures to Increase Compliance and Minimize Secondary Harms

Mandatory restrictions in the absence of social supports to minimize secondary harms are deeply unjust. Moreover, social supports maximize compliance with guidance and help maintain the public’s trust, bolstering the effectiveness of public health measures.33

Upon initiation of school and workplace closures and guidance or orders to stay at home, governments should act immediately to ensure safe, sanitary, and accessible housing conditions for all. Governmental responsibility should be exercised immediately to secure the health and safety of people in custody, detention, and foster care. Wherever possible, people in custody should be released from crowded conditions and provided with supports for housing and other essential needs.34 People experiencing homelessness should be exempted from enforcement of mandatory orders to shelter in place (as most, but not all orders currently in effect have provided). Moreover, safe, sanitary, and uncrowded shelter that is physically accessible for people with disabilities should be offered to people who are unhoused, experiencing homelessness, or living in communal settings. People who are experiencing domestic abuse should be proactively protected at a time when they may be cut off from outside contact and supports.35 Safe and sanitary housing regulations should be proactively enforced to mitigate increased exposure to lead, mold, pest infestations, and other hazards, particularly for people living in low-income, federally-financed, or rental housing.

Federal, state, and local governments are acting to provide legal protections to preserve employment, income, housing, and utilities and financial assistance and direct delivery of essential goods and services for those in need. Many of these measures are short-term, however. Long-term measures may be required as the pandemic and our response to it unfolds in the coming months. Over time, as community transmission is assessed to be minimal in some areas at some times, protective measures and accommodations will be particularly crucial for people who are at the highest risk of severe complications and death from Covid-19, who may need to stay at home even as others are able to return to work.

Though a relatively small number of vocal protesters have garnered media attention, the reality is that compliance with Covid-19 community mitigation measures has been widespread and willing for the most part so far. Due to logistical, legal, and ethical constraints, restrictions that are mandatory in theory rely on widespread voluntary compliance in practice. As levels of community transmission are assessed to be minimal in some places at some times, mandatory restrictions should be lifted and replaced with voluntary guidelines, but restrictions may need to be re-tightened periodically to keep the curve of the epidemic within health care capacity. Throughout this crisis, sustained social supports to justify and enable safe compliance with restrictions and recommendations will be absolutely crucial to the success of the public health response to Covid-19.

Judicial Review of Emergency Communicable Disease Control Orders and the Role of Voluntary Guidelines

Long-term, state-wide orders to close nearly all business operations and shelter in place were untested in US courts prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. A small number of court precedents reviewing emergency communicable disease control measures and quarantines of individuals suspected of being exposed provide some guidance to courts reviewing challenges to Covid-19 orders. In these pre-Covid cases, judges evince a strong desire to defer to the scientific judgments of elected officials. In Jew Ho v. Williamson, for example, Judge William Morrow assured authorities that he would “give the widest discretion” to actions taken “in the presence of a great calamity.”36 But he also affirmed his grave constitutional responsibility to review government intrusions upon civil liberties. “Is the regulation in this case a reasonable one?” he asked. “Is it a proper regulation, directed to accomplish the purpose that appears to have been in view? That is a question for this court to determine.”37

Judicial Review of Emergency Communicable Disease Control Measures in the Pre-Civil Rights Era

Quarantines imposed on individuals, homes, and geographic districts were not an uncommon occurrence in the 18th and 19th centuries. Cases adjudicating legal issues arising from quarantine orders were almost exclusively handled by the state courts, however, and federal rights were not widely understood to be implicated.38 At the turn of the 20th century, federal courts began to hear challenges based on individual rights protected under the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of due process and equal protection. In Pre-Civil Rights Era communicable disease control cases, judges applied standards of review that were considerably more deferential than the strict scrutiny standard that Civil Rights Era precedents would later adopt for review of infringements upon fundamental rights and suspect classifications (such as those based on race, ethnicity, or religious affiliation).

In Jew Ho v. Williamson, a 1900 opinion from a federal district court in California, Judge Morrow relied heavily on the affidavit of a medical doctor and (apparently former) public health official, Dr. J. I. Stephen, who offered scientific expertise on how bubonic plague spreads from person to person and place to place and public health methods for combatting it.39 Dr. Stephen, who appears to have been invoked as an expert by the plaintiffs, averred.

that no proper or scientific precautions have been taken by [the San Francisco board of health] to prevent the spread of … disease. [They] have proceeded from erroneous theories to still more erroneous and unscientific practices and methods of dealing with the same; for, instead of quarantining the supposedly infected rooms or houses in which … deceased persons lived and died, and the persons who had been brought in contact with and been directly exposed to said disease, [the] defendants have quarantined, and are now maintaining a quarantine over, a large area of territory, and indiscriminately confining therein between 10 and 20,000 people, thereby exposing, and they are now exposing, to the infection of the said disease said large number of persons.

Informed by Dr. Stephen’s affidavit, Judge Morrow demonstrated a remarkably nuanced understanding of the distinction between individual quarantines confining individuals ‘afflicted’ with a highly communicable disease “to their own domiciles until they have so far recovered as not to be liable to communicate the disease to others” with “the object … to confine the disease to the smallest possible number of people” and geographic quarantine (also known as cordon sanitaire), whereby officials “place 10,000 persons in one territory, and confine them there,” at which point “the danger of such spread of disease is increased, sometimes in an alarming degree, because it is the constant communication of people that are so restrained or imprisoned that causes the spread of the disease.”40 Morrow also decried the discriminatory character of the sanitary cordon, which operated almost exclusively against people of Chinese descent. His order took a measured approach, lifting the general quarantine “thrown around the entire district” while affirming the authority of city officials “to maintain a quarantine around such places as it may have reason to believe are infected by contagious or infectious diseases.”41

Jacobson v. Massachusetts, the 1905 case which the US Supreme Court upheld a compulsory vaccination mandate adopted during a smallpox outbreak,42 adopted a far more deferential posture toward the judgement of the Massachusetts legislature and Cambridge board of health as to matters of science. Jacobson was also an emergency powers case, though it has been widely applied in non-emergency contexts, such as challenges to school vaccination mandates. The Cambridge Board of Health adopted an adult smallpox vaccination mandate following its declaration of a local smallpox outbreak. Thus, the Court framed the case in terms of “authority to determine for all what ought to be done in an emergency.”43

The Jacobson Court grappled mightily with how to judge elected officials’ adoption of compulsory public health measures in the absence of perfect information about risks and benefits. Justice Harlan’s opinion quoted a lengthy passage from a New York state court decision upholding a school vaccination mandate to prevent smallpox outbreaks:

The appellant claims that vaccination does not tend to prevent smallpox, but tends to bring about other diseases, and that it does much harm, with no good….The common belief, however, is that it has a decided tendency to prevent the spread of this fearful disease, and to render it less dangerous to those who contract it…. The possibility that the belief may be wrong, and that science may yet show it to be wrong, is not conclusive; for the legislature has the right to pass laws which, according to the common belief of the people, are adapted to prevent the spread of contagious diseases…. While we do not decide, and cannot decide, that vaccination is a preventive of smallpox, we take judicial notice of the fact that this is the common belief of the people of the state, and, with this fact as a foundation, we hold that the statute in question is a health law, enacted in a reasonable and proper exercise of the police power.44

Jacobson upheld the compulsory vaccination mandate as consistent “with the liberty which the Constitution the United States secures to every person against deprivation by the State.”45 Justice Harlan recognized that individual liberty is not “an absolute right in each person to be, in all times and in all circumstances, wholly free from restraint.”46 Rather, “every well-ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may at times, under the pressure of great dangers, be subjected to such restraint, to be enforced by reasonable regulations, as the safety of the general public may demand.”47 Harlan upheld the emergency vaccination mandate on the grounds that the board of health reasonably believed “it was necessary for the public health or the public safety.”48 In closing, however, Harlan “observe[d]… that the police power of a state … may be exerted in such circumstances, or by regulations so arbitrary and oppressive in particular cases, as to justify the interference of the courts to prevent wrong and oppression.”49 The Court declined to “usurp the functions of another branch of government,” by “adjudg[ing], as matter of law, that the mode adopted under the sanction of the state, to protect the people at large was arbitrary, and not justified by the necessities of the case.”50 But its decision also recognized that the “acknowledged power of a local community to protect itself against an epidemic threatening the safety of all might be exercised in particular circumstances and in reference to particular persons in such an arbitrary, unreasonable manner, or might go so far beyond what was reasonably required for the safety of the public, as to authorize or compel the courts to interfere for the protection of such persons.”51

Surprisingly many courts have continued to employ Jacobson’s pre-Civil Rights Era standard of “non-arbitrary and justified by public health necessity” (with ‘necessity’ not being used in the strict sense of the word) to judge routine compulsory public health measures (especially school vaccination mandates) while declining to decide whether strict scrutiny applies.52

Judicial Review of Emergency Communicable Disease Control Orders During and After the Civil Rights Era

Lower federal court decisions on challenges to individual quarantine orders for smallpox and Ebola virus disease are also instructive for judges fielding Covid-19 constitutional challenges.53 Although these cases have been decided during and after the Civil Rights Era, in which courts recognized the importance of more searching judicial review to protect fundamental rights to liberty, their approach to scrutinizing emergency communicable disease control orders has been non-strict in ways that mirror Jacobson and Jew Ho (though without necessarily citing them).54

In 1963, the federal district court for the Eastern District of New York declined to release Ellen Siegel from a federal quarantine facility where she was being held after visiting Stockholm, Sweden at a time when it was designated a “small pox infected local area” by Swedish health authorities. 55 In US ex rel. Siegel v. Shinnick, Judge John Francis Dooling, Jr. carefully reviewed the International Sanitary Regulations adopted by the WHO, which deferred to the declarations of local health officials as to when a local area is “free of local infection.”56 He also noted WHO guidelines indicating that declaration of local infection could be safely terminated “twenty-eight days after the last reported case of small pox dies, recovers or is isolated.”57Siegel argued that the designation of Stockholm as affected by smallpox at the time of her visit was in error because (as both parties agreed) the most recently reported case had later been determined to be a false positive. Dooling could have done the math himself and determined that, following WHO guidelines, Stockholm could have been designated safe from smallpox prior to Siegel’s arrival. But instead he deferred to Swedish health authorities:

It does not appear that others are legally competent to (as they would be hopelessly handicapped in seeking to) make a determination on such a question as whether or not Stockholm can now be regarded as not an infected local area on the basis that the last reported case went into isolation [more than 28 days prior to Siegel’s arrival]; responsibility for applying that standard rests with the territorial health administration and depends on whether, also, all measures of prophylaxis have been taken and maintained to prevent recurrence of the disease. It is idle and dangerous to suggest that private judgment or judicial ipse dixit can, acting on the one datum of the date June 22 as the last identified and reported case, undertake to supercede [sic] the continuing declaration of the interested territorial health administration that Stockholm is still a small pox infected local area.58

Although he deferred to Swedish health authorities’ designation of Stockholm as an affected area, Judge Dooling carefully reviewed the actions of the federal Public Health Service, which ordered Siegel’s quarantine upon her return to the USA. In upholding the quarantine order, Dooling pointed to the importance of an individualized risk assessment, “taking into account previous vaccinations and the possibilities of her exposure to infection.”59 Siegel was initially asked to present a certificate of vaccination against smallpox, but she had failed to produce detectable antibodies following a series of vaccination attempts and could not be certified as successfully vaccinated. Dooling noted that federal health officials had not detailed Siegel’s husband, who apparently had been successfully vaccinated prior to the trip to Stockholm.60 The judge also emphasized the need to adopt less restrictive alternatives, where available. He urged “caution[] against light use of isolation,” which “is not to be substituted for surveillance unless the health authority considers the risk of transmission of the infection by the suspect to be exceptionally serious.”61

The order in Siegel was, however, highly deferential to federal health officials’ scientific risk assessment based on the best available evidence and relying on the precautionary principle. Dooling noted that “the judgment required is that of a public health officer and not of a lawyer used to insist[ing] on positive evidence to support action; their task is to measure risk to the public and to seek for what can reassure and, not finding it, to proceed reasonably to make the public health secure. They deal in a terrible context and the consequences of mistaken indulgence can be irretrievably tragic. To supercede [sic] their judgment there must be a reliable showing of error.”62

Dooling did not identify the level of scrutiny he applied in Siegel, nor did he cite Jacobson or any other case in denying the plaintiff’s habeas petition. He described the ‘medical men’ who testified on behalf of the federal defendants as “shar[ing] a concern that was evident and real and reasoned.”63 In a footnote, Dooling noted that the procedure followed by health officials was not directly constrained by federal or international regulations, but “remains a function of the gravity of the situation as measured by their expert judgments dispassionately formed.”64 His description of the defendant’s ‘expert’ and “dispassionate[]} determinations as not only reasoned but “evident and real” appears to be consistent with the “non-arbitrary and justified by the necessities of the case” standard applied by the Jacobson Court.

More recently, state and federal courts fielded two lawsuits involving Kaci Hickox, a nurse who, upon her return from treating Ebola patients in Sierra Leone, was briefly detained by federal health authorities for a health screening at Newark International Airport, then handed over to New Jersey officials who held her under a state quarantine order, then released to her partner’s home state of Maine where the governor ordered state troopers to guard her home and follow her movements while health officers from the state’s Center for Disease Control monitored her temperature and symptoms daily. First, a state trial judge in Maine was asked to impose a court-ordered home quarantine,65 which Hickox resisted on the grounds that it was not based on a reasonable assessment of the risk she posed to others.66 Hickox later filed a suit for damages in the federal district court in New Jersey.67

In Hickox v. Mayhew, Maine state trial court judge Charles LaVerdiere, followed his predecessors in looking to guidelines from health agencies. In the press, Hickox argued that because that she did not have any symptoms and the best available evidence demonstrated that transmission by asymptomatic individuals was not a concern, an involuntary quarantine was inappropriate.68 Judge LaVerdiere ultimately determined that Hickox could properly be subjected to an order mandating direct active monitoring (with direct observation by state health authorities at least once per day to review symptoms and monitor temperature with a second daily follow-up by phone), a less restrictive limitation on her liberty than the home quarantine restrictions the state had requested. In reaching this result, the judge noted that “the only information that the Court has before it regarding the dangers of infection posed by” Hickox, was from the affidavit of “Shiela Pinette, D.O., Director of the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, together with the attachments from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.”69 In particular, both parties agreed that Hickox was “asymptomatic (no fever or other symptoms consistent with Ebola), as of the last check pursuant to her direct active monitoring.”70 Judge LaVerdiere followed Dr. Pinette’s conclusion that the imposition of direct active monitoring was functionally dictated by CDC’s (voluntary) guidelines: “Therefore the guidance issued by U.S. CDC states that she is subject to Direct Active Monitoring. Health care workers in the “some risk” category require direct active monitoring for the 21-day incubation period.”71 In his concluding ‘observations,’ LaVerdiere noted that he was “fully aware of the misconceptions, misinformation, bad science and bad information being spread from shore to shore … with respect to Ebola” and “that people are acting out of fear and that this fear is not entirely rational. However, whether that fear is rational or not, it is present and it is real.” The judge chided Hickox to ensure that her “actions at this point, as a health care professional, need to demonstrate her full understanding of human nature and the real fear that exists” and “guide herself accordingly.”

In a subsequent suit arising out of her initial quarantine in New Jersey, Hickox’s constitutional arguments were rejected, but she eventually reached a settlement on state law grounds that included new protections for people quarantined in New Jersey.72 In Hickox v. Christie, federal district court judge Kevin McNulty had the benefits of time and hindsight. He fielded the suit for damages several months after the quarantine on Hickox had been lifted, when it was clear that she never contracted Ebola virus and Ebola panic among Americans had passed. Still, Judge McNulty relied on CDC guidance to justify the state’s quarantine. Noting that he did “not need to make any finding as to its accuracy,” he “simply note[d] that the authorities could reasonably have relied on it” at the time they detained Hickox.73 Unlike LaVerdiere, McNulty took a somewhat more skeptical stance toward CDC guidance, which adopted a less cautious approach toward exposed but asymptomatic individuals than New Jersey officials applied. McNulty pointed out that CDC guidance did not automatically dictate how Hickox should have been handled, because the guidance “contain[ed] recommendations, and it note[d] the importance of public health officials’ exercise of their judgment.”74

McNulty declined to formally endorse requirements of individualized risk assessments and the least restrictive means, which public health law experts have urged are constitutionally required for mandatory quarantines of individuals believed to pose a risk of transmitting communicable disease. He “assume[d] without deciding that the… ‘individualized assessment’ of the individual’s illness and ability or willingness to abide by treatment can, mutatis mutandis, be adapted to the situation of a temporary detention for observation based on a risk of infection.”75 Ultimately, he concluded that “an erroneous application of CDC guidelines does not correspond to a constitutional cause of action.”76

Official (but Voluntary) Community Mitigation Guidelines Issued During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Federal guidelines have struggled to keep pace with the restrictions imposed by governments in response to the spread of SARS-COV-2. With respect to community mitigation and non-pharmaceutical interventions, on March 12, CDC quietly posted a document titled “Implementation of Mitigation Strategies for Communities with Local COVID-19 Transmission.”77 Described as “a framework for actions which local and state health departments can recommend in their community to both prepare for and mitigate community transmission of COVID-19,” this document recommended that “these actions should be guided by the local characteristics of disease transmission, demographics, and public health and healthcare system capacity.” 78 In places with ‘substantial’ community transmission, defined as occurring when there is “[l]arge scale community transmission,” with “healthcare staffing significantly impacted, multiple cases within communal settings like healthcare facilities, schools, mass gatherings etc.,”79 the framework recommended that “[a]ll individuals should limit community movement and adapt to disruptions in routine activities (e.g., school and/or work closures) according to guidance from local officials.”80 The framework additionally recommended that in periods of substantial community transmission, organizations should “cancel community and faith-based gatherings of any size.”81

Separately, CDC issued guidelines for large community events and mass gatherings recommending cancelation of “gatherings of more than 10 people for organizations that serve higher-risk populations.”82 Notably, even as nearly every state issued mandatory orders restricting the operation of commercial businesses, CDC’s only guidance for “keeping commercial establishments safe” recommended disinfection of surfaces, steps to stagger customer flow and frequent hand washing,83 while the CDC website suggested businesses “[c]onsider establishing policies and practices for social distancing … if recommended by state and local health authorities.”84

In mid-March, CDC also issued a series of specific guidance documents for specific localities and states, including the cities of Santa Clara, Seattle, and New Rochelle, and the states of Florida and Massachusetts. Notably the CDC guidance for Santa Clara recommended ‘laser focused’ and less restrictive interventions that were inconsistent with the county-wide shelter-in-place order the Santa Clara Health Officer issued a day earlier.85 CDC guidance for other locations similarly recommended less stringent measures than state and local authorities had already adopted.

The White House issued competing guidance on March 16. The “15 Days to Stop the Spread” guidelines, later amended to ‘30 Days,’ recommended that certain groups—people who feel ill, people who test positive for coronavirus and their family members, and people who are older or who have serious underlying health conditions that put them at increased risk—should stay at home. It also recommended that everyone should “avoid social gatherings in groups of more than 10 people,” “eating or drinking at bars, restaurants, and food courts,” and “discretionary travel, shopping trips, and social visits.”86 With respect to closures, the guidelines noted that “[g]overnors in states with evidence of community transmission should close schools in affected and surrounding areas” and “[i]n states with evidence of community transmission, bars, restaurants, food courts, gyms, and other indoor and outdoor venues where groups of people congregate should be closed.”87 This guidance adopted a far less cautious stance toward mitigating the spread of novel coronavirus than the mandatory stay-at-home and non-essential business closure orders in effect in the majority of states at the time the White House guidelines were released.

Subsequently, on April 16, the White House released new “Guidelines for Opening Up America Again,” which set forth a phased approach to resuming social gatherings, resuming elective medical procedures, and reopening schools and the types of businesses that the previous White House guidelines had recommended for closure (including bars, restaurants, gyms, and venues where groups of people gather)..88 The guidelines established ‘gating’ criteria for reopening ‘large venues’ and gyms after a sustained downward trajectory in the number of syndromic and reported cases for 14 days and at a point when hospitals are able to treat patients without resorting to crisis standards of care and to test health care workers exposed to novel coronavirus. If the same gating criteria are met following the reopening of gathering places in phase one, states were advised to proceed to phase two, in which schools, bars, and other higher-risk settings are reopened.

Judicial Review of Emergency Orders During the Covid-19 Pandemic

The few courts that have reviewed early Covid-19 civil liberties challenges to date have followed pre-Covid precedents in relying on voluntary guidelines from international and federal authorities, but that may prove more challenging as restrictions imposed by state and local governments exceed what CDC has endorsed, particularly given that the White House is offering guidelines that conflict with CDC’s.

In Binford v. Sununu, a New Hampshire state trial court upheld the state’s ban on gatherings of 50 or more people (New Hampshire later lowered the limit for groups) and prohibition of dine-in service at bars and restaurants, rejecting the plaintiffs’ argument that these restrictions impermissibly infringed upon his rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments.89 In an opinion issued on March 25, 9 days after the White House’s “15 Days to Stop the Spread” guidance went into effect, Judge John C. Kissinger noted that these restrictions were “clearly supported by the recommendations put forth by the White House and CDC” without specifying which recommendations were applicable.90

Judge Kissinger undoubtedly reached the right result in upholding the ban on gatherings of 50 or more people, but he based his holding on troubling reasoning. Adopting the position that the governor has “authority to suspend civil liberties” in an emergency, the court applied a “good faith/some factual basis” test to uphold the restrictions. This test, which comes from an 11th Circuit case upholding a nightly curfew in Miami-Dade County in the aftermath of Hurricane Andrew,91 eschews the courts’ constitutional responsibility to determine whether the state has adopted “a proper regulation, directed to accomplish the purpose that appears to have been in view?” in the words of Judge Morrow in Jew Ho.

The lack of clear guidelines from CDC supporting the state’s reasonable measure may have played a role in Judge Kissinger’s decision to resort to the extreme of adopting a suspension rule. In its objection to the plaintiff’s complaint, the state did not argue for suspension. It cited the 11th circuit hurricane case, but without specifically referring to or endorsing the suspension rule. The state also cited specific CDC and White House guidelines, which it described as recommending cancelation of planned gatherings of 10 or more people,92 but (as noted above) the CDC’s guidance was limited to organizations “that serve higher risk populations” and neither guideline specifically endorsed mandatory limits on bar and restaurant service. In a situation where conflicting guidelines have been issued, a court applying a rational basis test or Jacobson’s standard should defer to the choice of a political branch to follow the more cautious guidelines. In challenges based on civil liberties, this will typically result in upholding restrictions. But at the time Binford was decided, no federal guidelines recommended bans on gatherings for the general population, leaving the state with little cover to defend its ban.

In a higher profile case, the Fifth Circuit upheld application of the Texas emergency order prohibiting elective medical care to all abortions, partially on the grounds that CDC had recommended preserving face masks and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services had recommended limiting unnecessary medical procedures to reduce opportunities for disease transmission.93In re Abbott relied on a warped characterization of Jacobson as establishing “the controlling standards, established by the Supreme Court over a century ago, for adjudging the validity of emergency measures.”94 The majority set aside the heightened review typically applied to restrictions on abortion in favor of a rule that “the scope of judicial authority to review rights-claims” during “a public health crisis” is limited to cases where “a statute purporting to have been enacted to protect the public health, the public morals, or the public safety, has no real or substantial relation to those objects, or is, beyond all question, a plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law.”95 Moreover, the Fifth Circuit suggested that in a crisis, this minimal level of scrutiny applies equally to “one’s right to peaceably assemble, to publicly worship, to travel, and even to leave one’s home.”96 Although not explicitly endorsing a suspension principle, In re Abbott’s manipulation of Jacobson achieves essentially the same result: applying an exceedingly low standard of review in times of crisis.

Conclusion: A Call for Greater Transparency and Accountability for Voluntary Guidelines

As Robert Gatter argued in his critique of Ebola quarantine cases, judges’ “responsibility to assure [relevant scientific] facts are discovered and accounted for … is inherent in even the most deferential standard of judicial review. A court asked to address whether a public health agency has acted reasonably and without abusing its discretion need not simply defer to the expertise of the agency without requiring that the agency to identify and explain the logic the agency deployed to reach its conclusion that quarantine was appropriate.”97 The same is true of officials charged with developing emergency communicable disease control guidelines that, while technically voluntary, are likely to be relied on to enforce involuntary—and highly intrusive—measures by state and local governments.

Clear guidelines developed by CDC through transparent processes that include publication of peer reviewed analyses and literature reviews give states important cover for defending emergency orders in the face of civil liberties challenges. In the absence of an ‘easy’ route to defending state and local restrictions as consistent with evidence-based guidelines, judges who wish to uphold emergency orders may resort to less searching forms of review. Though the result—upholding the restrictions—may be the right one in most cases, a knee-jerk approach that endorses a governor’s authority to suspend the civil liberties protected by the federal constitution will not be helpful to developing a sustainable long-term strategy for mitigating the current pandemic or for future public health law preparedness efforts. As the Fifth Circuit’s coronavirus abortion decisions demonstrate, when courts abandon the ordinary levels of review applicable to fundamental rights, they may permit government over-reach and opportunism.

Even if conflicting guidelines are released—as has been the case with separate sets of Covid-19 guidelines coming from the White House and the CDC—courts following Jacobson’s standard of review should defer to elected officials’ choice as to which guidelines they adopt. A cautious set of guidelines may provide adequate cover to states to enforce some forms of community mitigation even if alternative, less cautious guidelines are available. And if a higher standard of review applies, as is the case for abortion restrictions, then the availability of a less restrictive alternative can and should lead courts to question the necessity of harsh limits.

Governments must earn the public’s trust by acting transparently, fairly, and effectively and communicating their plans and guidance clearly. The way we respond to the Covid-19 crisis—how state and local governments wield authoritarian powers necessary to combat the spread of disease and how we protect the people who are most vulnerable to the disease itself and the secondary harms that will arise out of our efforts to combat it—will shape public health law and the society we live in for generations to come.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

See Julia Prodis Sulek, Meet the Doctor Who Ordered the Bay Area’s Coronavirus Lockdown, the First in the U.S., Mercury News (Mar. 29, 2020), https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/03/29/she-shut-down-the-bay-area-to-slow-the-deadly-coronavirus-none-of-us-really-believed-we-would-do-it/.

Mark A. Rothstein, From SARS to Ebola: Legal and Ethical Considerations for Modern Quarantine, 12 Ind. Health L. Rev. 227, 246 (2015); see also Wendy K. Mariner, George J. Annas, and Wendy E. Parmet, Pandemic Preparedness: A Return to the Rule of Law, 1 Drexel L. Rev. 341 (2009); Lawrence O. Gostin and Lindsay F. Wiley, Public Health Law: Power, Duty, Restraint (3d. ed. 2016).

See Rebecca L. Haffajee and Michelle M. Mello, Thinking Globally, Acting Locally—The U.S. Response to Covid-19, NEJM.org (Apr. 2, 2020), https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2006740.

State Actions to Mitigate the Spread of COVID-19, KFF.org, https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/#socialdistancing (last visited Apr. 22, 2020).

Neil M. Ferguson et al., Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team Report 9: Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID-19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand (Mar. 16, 2020),https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf.

Id.

Ruiyun Li et al., Substantial Undocumented Infection Facilitates the Rapid Dissemination of Novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV2), Science (Mar. 16, 2020), at https://science.sciencemag.org/content/early/2020/03/24/science.abb3221.long.

Robert J. Glass et al., Targeted Social Distancing Designs for Pandemic Influenza, 12, Emerging Infectious Diseases 1671 (2006); Noreen Qualls et al., Community Mitigation Guidelines to Prevent Pandemic Influenza—United States, 2017, 66 Mortality & Morbidity Weekly Rprt. 1 (2017).

Kylie E C Ainslie et al., Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team Report 11: Evidence of Initial Success for China Exiting COVID-19 Social Distancing Policy After Achieving Containment (Mar. 24, 2020), https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-Exiting-Social-Distancing-24-03-2020.pdf; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Rapid Expert Consultation on Social Distancing for the COVID-19 Pandemic, https://www.nap.edu/read/25753/chapter/1 (Mar. 19, 2020).

Binford v. Sununu, No. 217–2020-CV-00152 (N.H. Super. Ct. Mar. 25, 2020) (mem.); Nigen v. New York, No. 20-CV-1576 (E.D.N.Y Mar. 29, 2020).

Community Preventive Services Task Force, Emergency Preparedness and Response: School Dismissals to Reduce Transmission of Pandemic Influenza (August 2012) (recommending school closures for pandemic influenza after surveying studies supporting the effectiveness of school closures for influenza control).

KFF.org, supra note 4.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Qualls et al., supra note 8.

KFF.org, supra note 4.

Binford v. Sununu, supra note 10.

Nigen v. New York, supra note 10.

KFF.org, supra note 4.

See Mariner et al., supra note 2.

See Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507, 531 (2004) (“We reaffirm today the fundamental nature of a citizen’s right to be free from involuntary confinement by his own government without due process of law, and we weigh the opposing governmental interests against the curtailment of liberty that such confinement entails.”).

Menotti v. Seattle, 409 F.3d 1113 (2005).

Mayhew v. Hickox, No. CV-2014-36, Maine Trial Court Order (Oct. 31, 2014).

Anthony Michael Kreis, Contagion and the Right to Travel , https://blog.harvardlawreview.org/contagion-and-the-right-to-travel/ (Mar. 27, 2020).

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 (1941).

Compagnie Francaise de Navigation a Vapeur v. Louisiana State Board of Health, 186 U.S. 380 (1902).

Kreis, supra note 25.

Jew Ho v. Williamson, 103 F. 10 (N.D. Ca. 1900).

Howard Markel et al., Nonpharmaceutical Influenza Mitigation Strategies, US Communities, 1918–1920 Pandemic, 12 Emerging Infectious Diseases 1961 (2006).

Polly Price, Epidemics, Outsiders, and Local Protection: Federalism Theater in the Era of the Shotgun Quarantine, 19 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 369 (2016).

KFF.org, supra note 4.

Emily A. Benfer and Lindsay F. Wiley, Health Justice Strategies to Combat COVID-19: Protecting Vulnerable Communities During A Pandemic, Health Affairs Blog, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200319.757883/full/ (Mar. 19, 2020).

Oluwadamilola T. Oladeru, Adam Beckman & Gregg Gonsalves, What COVID-19 Means For America’s Incarcerated Population—And How To Ensure It’s Not Left Behind, Health Affairs Blog, https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200310.290180/full/ (Mar. 10, 2020).

Alisha Haridasani Gupta and Aviva Stahl, For Abused Women, a Pandemic Lockdown Holds Dangers of Its Own. N.Y. Times,https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/us/coronavirus-lockdown-domestic-violence.html (Mar. 24, 2020).

Jew Ho, 103 F. at 21. Another case reviewing a geographic quarantine reached the U.S. Supreme Court two years later. In Compagnie Francaise de Navigation a Vapeur v. Louisiana State Board of Health, “[p]erhaps because the case was brought by [a] steamship company (seeking to recover the cost of caring for the passengers during the quarantine) and not the passengers, neither the majority nor the dissent addressed possible violations of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in applying [a quarantine applicable to anyone attempting to leave or enter seven parishes] only to immigrants on one ship.” Rothstein, supra note 2, at 246.

Jew Ho, 103 F., at 21.

Rothstein, supra note 2, at 246–249 (2015) (surveying state case law).

Id. at 22. Dr. Stephen described himself as having “held various official positions, such as surgeon to the police, medical officer of health, parish medical officer, and public vaccinator,” and having, “for the past thirteen years in the state of California,” “given much time and study to the literature of the bubonic plague.” He also noted that he was “the regularly appointed physician of the Chines [sic] Empire Reform Association, which numbers several thousand Chinese residents in the state of California.” Id. at 24.

Id.

Id. at 26.

197 U.S. 11 (1905).

Id. at 27.

Id. at 35 (quoting Viemeister v. White 179 N. Y. 235 (1904)).

Id. at 25.

Id.

Id. at 29.

Id. at 26.

Id. at 29.

Id. at 28.

Id.

See, eg, Phillips v. City of New York, 775 F.3d 538 (2d. Cir. 2015); Workman v. Mingo County Bd. of Educ., 419 Fed.Appx. 348 (4th Cir. 2011).

See Wendy E. Parmet and Michael S. Sinha, Covid-19—The Law and Limits of Quarantine, NEJM.org, https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2004211 (Apr. 9, 2020). Throughout the 20th century, states have continued to use similar orders to isolate patients infected with tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections. See Wendy E. Parmet, Quarantining the Law of Quarantine: Why Quarantine Law Does Not Reflect Modern Constitutional Law, 9 Wake Forest J. L. & Pol’y 1 (2018–19). But these orders do not trigger the same degree of deference from courts that emergency orders adopted under conditions that limit the feasibility of rigorous scientific risk assessments and so I do not address them here, given limits on space.

Id.

219 F.Supp. 789, 790 (E.D.N.Y. 1963).

Id. (citing the International Sanitary Regulations of 1951).

Id.

Id. at 790–91.

Id. at 791.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id.

Maine’s quarantine law provided for judicially imposed quarantine orders. 22 M.R.S. Section 811(3) (2014).

Mayhew v. Hickox, No. CV-2014-36, Maine Trial Court Order (Oct. 31, 2014).

Hickox v. Christie, 205 F.Supp.3d 579 (D. N.J. 2016); see also Liberian Cmty. Ass’n of Conn. v. Malloy, No. 3:16-cv-00201, 2017 WL 4897048 (D. Conn. Mar. 30, 2017) (dismissing suit for damages by class of individuals quarantined under state orders in Connecticut based on travel in Ebola-affected countries).

Sydney Lupkin and Aaron Katersky, Nurse Says She Won’t Have Officials Violate ‘My Civil Rights,’ ABC News, https://abcnews.go.com/Health/ebola-america-nurse-maine-health-officials-violate-civil/story?id=26542668 (Oct. 29, 2014).

Mayhew v. Hickox, supra note 66.

Id.

Id.

Marc Santora, New Jersey Accepts Rights for People in Quarantine to End Ebola Suit, N.Y. Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/27/nyregion/new-jersey-accepts-rights-for-people-in-quarantine-to-end-ebola-suit.html (July 27, 2017).

For a critical assessment of CDC’s Ebola guidance and its effect on related court decisions, see Robert Gatter, Ebola, Quarantine, and Flawed CDC Policy, 23 U. Miami Bus. L. Rev. 375 (2015); see also Robert Gatter, Three Lost Ebola Facts and Public Health Legal Preparedness, 12 St. Louis U. J. Health L. & Pol’y 191, 200 (2018).

Hickox v. Christie, 205 F.Supp.3d at n.10.

Id. at 598.

Id. at 599.

CDC, Implementation of Mitigation Strategies for Communities, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/community-mitigation-strategy.pdf (Mar. 12, 2020, last visited Apr. 4, 2020).

Id. at 1.

Id. at 9.

Id. at 7.

Id.

CDC, Resources for Large Community Events & Mass Gatherings, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/large-events/mass-gatherings-ready-for-covid-19.html (last updated Mar. 15, 2020).

CDC, What Every American and Community Can Do Now to Decrease the Spread of the Coronavirus, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/workplace-school-and-home-guidance.pdf (last visited Apr. 4, 2020).

CDC, Interim Guidance for Businesses and Employers to Plan and Respond to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/guidance-business-response.html (last updated Mar. 21, 2020).

CDC, CDC’s Recommendations for 30 Day Mitigation Strategies for Santa Clara County, California, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/Santa-Clara_Community_Mitigation.pdf (last visited Apr. 4, 2020).

Whitehouse.gov, 15 Days to Slow the Spread, https://www.whitehouse.gov/articles/15-days-slow-spread/ (Mar. 16, 2020, last accessed Apr. 4, 2020). 15 Days to Slow the Spread was later revised and replaced with 30 Days to Slow the Spread, The President’s Coronavirus Guidelines for America (Mar. 30, 2020), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/03.16.20_coronavirus-guidance_8.5x11_315PM.pdf.

Id. at 2.

Whitehouse.gov, President Donald J. Trump Announces Guidelines for Opening Up America Again, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/president-donald-j-trump-announces-guidelines-opening-america/ (press release, Apr. 16, 2020); Whitehouse.gov, Guidelines: Opening Up American Again, https://www.whitehouse.gov/openingamerica/ (Apr. 16, 2020).

Binford v. Sununu, supra note 10.

Id. at 14.

Smith v. Avino, 91 F.3d 105, 109 (11th Cir. 1996) (“In an emergency situation, fundamental rights such as the right of travel and free speech may be temporarily limited or suspended.” (citing Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964); Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)).

Binford v. Sununu, Objection to Emergency Motion for Preliminary Injunction and Permanent Injunction, https://www.courts.state.nh.us/caseinfo/pdf/civil/Sununu/031920Sununu-obj.pdf (Mar. 19, 2020).

In re Abbott, No. 20–50264, 2020 WL 1685929 (5th Cir. Apr. 7, 2020) (citing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Strategies for Optimizing the Supply of Facemasks, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/face-masks.html; CMS Adult Elective Surgery and Procedures Recommendations, https://www.cms.gov/files/document/31820-cms-adult-elective-surgery-and-procedures-recommendations.pdf).

Id.

Id.

Id.

Gatter, Three Lost Ebola Facts, supra note 73, at 211.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.