Abstract

Objectives

To explore the impact of the provision of care of forcibly displaced Syrian mental health professionals (MHPs) to Syrian clients in the community given shared experiences and backgrounds with clients.

Design

A qualitative study using thematic analysis of in-depth semistructured interviews to explore shared realities, self-disclosure and the impact of providing therapy.

Setting

Syrian MHPs operating in Gaziantep and Istanbul, Turkey, were interviewed.

Participants

Sixteen forcibly displaced Syrian MHPs (eight male, eight female) aged between 24 and 54 years (M=35, SD=8.3) who provided care to the displaced Syrian community in Turkey.

Results

All workers described having a shared reality with their clients as helpful in therapy and a smaller proportion described it as a vulnerability. All described their work with Syrian clients as fulfilling and most described it as distressing. Participants referred to self-care, supervision, peer-support and personal therapy as a means to cope.

Conclusions

This study provides the first insight into the shared experiences of the ongoing trauma, loss and violations resulting from the ongoing Syrian conflict from the perspective of Syrian MHPs, adding to the literature of the professional issues and ethical duty to protect health workers in conflict settings.

Keywords: quality in health care, medical education & training, mental health, qualitative research, adult psychiatry

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to explore the experiences of forcibly displaced Syrian mental health workers and the shared reality of Syrian mental health workers and their Syrian clients using in-depth semistructured interviews and thematic analysis.

The first author is an Arabic speaker and mental health professional who interviewed participants in their native Arabic language.

This is an exploratory study of a small sample of forcibly displaced mental health workers in Turkey.

Due to the limited literature on Syrian mental health workers, these findings have implications for the ethical duty to protect Syrian mental health workers through the provision of adequate support in conflict and post-conflict settings.

Background

The ongoing Syrian conflict, seen as the worst humanitarian crisis of our time,1 has led to the displacement of half of Syria’s population, with over 13.1 million Syrians in need of humanitarian assistance leading to an ongoing public health crisis.2 The Syrian healthcare community has been a target of the military strategy led by the Syrian government, with reports of 478 attacks on medical facilities with 830 medical personnel killed since the beginning of the conflict3 and ongoing systematic violations of international humanitarian law, including the use of missiles, sniper and chemical attacks on hospitals and ambulances and the torture of healthcare workers.4 5 The majority of published literature sheds light on the impact of medical personnel, yet to our knowledge no literature exists on the impact of the conflict on mental health workers.

Widely endorsed global mental health programmes and guidelines emphasise the importance of working with communities and influential community figures, and where specialist support is required, guidelines recommend referring clients for evidence-based trauma therapies such as eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) and trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy where trained and supervised therapists are available.6–8 Consequently, expatriate Syrian mental health professionals (MHPs), various Syrian non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and international NGOs (INGOs) have made initiatives to provide training and supervision for evidence-based therapies to displaced Syrians.9–11 While doing so mobilises resources, reduces language barriers and enhances cultural sensitivity, it also comes with challenges including high case loads with reduced opportunities for supervision given the lack of qualified supervisors relative to demand, with potential negative emotional consequences.

The term ‘shared traumatic reality’ refers to situations where both professional and client have been exposed to the same communal disaster, and ‘double exposure’ refers to health professionals’ exposure both as professionals providing a service and as members of the community.12 13 Most studies of a shared traumatic reality are based on quantitative enquiry. A qualitative meta-synthesis of studies of the impact of trauma work on trauma workers found themes related to emotional and somatic reactions to trauma work such as sadness, helplessness, nausea and despair, changes to schemas and behaviours such as questioning themselves and their lives and perceiving the world as unsafe.14 While much research focuses on the potential negative consequences, recent research is acknowledging the potential for shared resilience in a traumatic reality.15

Very little literature exists on Syrian MHPs warranting in-depth exploration to understand their context and experience. Despite intravariability and intervariability within Arab cultures, the influence of Syrian culture contributes to differential conceptualisations, processes and experiences such as kissing and hugging strangers in same-sex greetings, asking about family and offering food or drink given the deep-rooted values of family and hospitality in Arab culture16 17 likely influencing the MHP–client dyad. Given these Syrian-Arab cultural frameworks and the shared ongoing trauma reality of Syrian MHPs and clients, it is unclear what this reality looks like and it how differs (or not) from a context of Western mental healthcare.

In a typical Western therapeutic context, self-disclosure is used cautiously, occurs infrequently and often relates to MHPs’ professional background rather than personal details.18 Disasters, regardless of geographical location, often create boundary ambiguity between the personal and professional with the penetration of demands from neighbours, friends and acquaintances, which can lead to burnout and strong countertransference arousal responses.19 A shared traumatic reality creates a feeling of universality leading to increased MHP self-disclosure.20 Appropriate self-disclosure allows the MHPs, as the ‘wounded healer’,21 to show their resourcefulness and to instil hope in clients of healing and recovery22 23; at the same time, increased self-disclosure within a shared reality can increase MHPs’ vulnerability for distress.24 25

It is unclear how or whether MHPs’ self-disclosure, in any capacity, features within these therapeutic dyads. It is expected that a shared reality in the context of Syrian culture may lend itself to MHPs’ self-disclosure, particularly within Turkey where Syrians are living within a small city, and that there are very few MHPs relative to residents. Many Syrian MHPs are themselves forcibly displaced, have witnessed and experienced traumatic events and, given the ongoing nature of the conflict, have an ongoing sense of hopelessness and loss. The term ‘forcibly displaced’ is used throughout this paper to capture those who are seeking asylum as well as refugees. The Syrian MHP–client dyad creates a shared reality that, to the researchers’ knowledge, has not been explored. An investigation of this context is warranted, along with what allows Syrian MHPs to continue to function in their capacity as healers, and what coping consists of within a displaced Syrian context.

This research aims to generate knowledge carved directly from Syrian MHPs’ experiences of providing therapy within a shared Syrian culture and displacement context.

Methods

Semistructured interviews were conducted in Arabic by the first author (AH) with forcibly displaced Syrian MHPs across two cities in Turkey, Istanbul and Gaziantep, the latter being a city 97 km north of Aleppo, Syria, in August and November 2017. Turkey is home to the largest number of Syrian refugees and the majority live along the southern border, with around half a million Syrians living in Gaziantep, a city used as a hub for cross-border support, hosting Syrian and INGOs. Trauma Aid UK, an INGO who provide specialist trauma training for Syrian health professionals in Turkey, facilitated the recruitment of participants.

The interviewer, AH, is a female Iraqi British MHP with clinical experience of mental health and conflict, conducting research as part of her doctoral thesis. It is likely that her characteristics have influenced all levels of the research cycle. Through reflexivity, AH used her clinical experience and cultural background to place herself in a unique position to carry out this research using experiential knowledge to enhance understanding. Participants were open to discussion during interviews, and all expressed keenness to participate given the potential for this research to help others.

The study aimed to (1) investigate the nature and influence of the shared culture and experiences of forced displacement within the Syrian MHP−client dyad, (2) explore the nature and impact of MHPs’ disclosure of shared experiences and (3) examine the perceived impact of providing therapy on MHPs and the associated means of coping. Reporting adheres to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research recommendations.26

Participants

Participants consisted of a purposive sample of 16 forcibly displaced Syrian MHPs residing in Turkey working with Syrian clients, aged between 24 and 54 years (M=35, SD=8.3), 8 male and 8 female, 12 psychologists and 4 psychiatrists. Participants were recruited through Trauma Aid UK’s mailing list and word of mouth. All participants were given information sheets and consent forms (in Arabic). Participants were aware prior to interview that participation was entirely voluntary, the interviewer was not affiliated with Trauma Aid UK, and all information provided would be encrypted, stored securely and anonymised through the use of identification codes throughout analysis and dissemination. Permission for audio recording was sought and granted. Interviews were recorded using the Olympus DS-3500 recorder which protects against unintended access by a 128-bit real-time file encryption. Interviews were conducted either in Gaziantep (n=11), Istanbul (n=3) or via Skype (n=2) and lasted between 40 and 70 min. The sample size was determined by data saturation; the degree to which new data repeated what was expressed in previous data.27

Measurement and analysis

The interview schedule was guided by the research questions and structured in a way to encourage participants to tell their story using three basic narrative structures; a beginning (such as ‘In what way do you experience similarities between you and your clients?’), in which the setting was described, a middle which contains a series of obstacles and attempted solutions (eg, ‘Do you talk with your clients about your own experiences?’) and an ending or resolution (eg, ‘What resources do you draw on that help with the challenging aspects of doing therapy?’).28 Given that little is known in the literature about this sample, open-ended, exploratory questions were used29 as well as externalising questions derived from a narrative approach to encourage participants to feel more comfortable to have an open dialogue.30 The research aimed to be grounded in examples and these were elicited where relevant.31 There were no changes made to the interview schedule over the course of the research.

A thematic analysis was conducted by AH using an inductive approach following the six steps recommended by Braun and Clarke32 using NVivo V.11 software. AH and two bilingual British Syrian health professionals transcribed the interview from Arabic audio to English script, and each script was read and re-read and systematically coded, giving full and equal attention to each item. A peer researcher independently coded a randomly chosen transcript using the same procedure outlined above, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. AH used mind maps to construct a thematic structure while being mindful of personal biases and influences. These themes were reviewed with the research team (KS, AW) to discuss whether this was an accurate depiction; consequently, themes were renamed and reorganised. Data analysis took place between December 2017 and April 2018.

Patient and public involvement

No patients or members of the public were involved in the conduct of this research.

Results

Situating the context

Prior to presenting the main themes emerging from the interviews, the context in which the Syrian MHPs described working is presented here. Syrian MHPs spoke of a number of facilitators to mental health provision. All participants referred to a number of specific psychological tools such as receiving psychological therapy training sessions as well as non-specific tools such as adopting an empathic, non-judgmental stance. Flexible ways of working through Skype or WhatsApp and providing therapy in people’s homes also facilitated therapy. Participants spoke of the importance of psychosocial support including the use of psychological first aid and linking clients to activities and social centres.

The main thing is to provide people with their main needs, not only food and water but also their human rights. We tried to change the mentality of the psychologists and the psychological workers to be able to support the people affected by the crisis. (P5)

There were also a number of barriers. Participants reported feeling under pressure due to high workloads and consequently only being able to provide a limited number of sessions. Participants stated that clients were reluctant to talk about their mental health problems and traumatic experiences, especially sexual abuse, with a general stigma present within the Syrian community accompanied by a lack of awareness of psychology.

They always say: ‘Am I a crazy person?’ I face this word ‘crazy’ a lot. (P1)

Some expressed the need for more trained therapists, risk management staff and sensitive interpreters. Financial difficulties were described both as a barrier to the provision of adequate mental healthcare and training and to patients accessing services due to not being able to travel to sessions.

Main themes

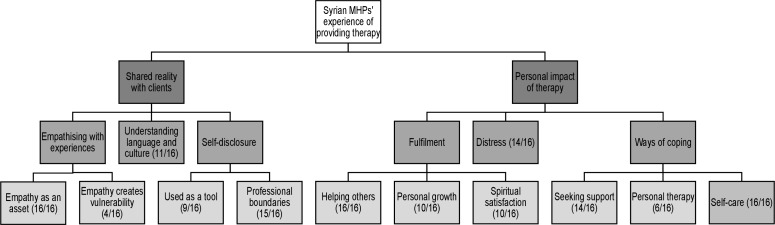

Analysis led to two overarching themes of shared characteristics and personal impact, with 6 themes and 10 subthemes; figure 1 illustrates these themes.

Figure 1.

Thematic map. Emergent overarching themes, themes and subthemes with participant endorsement.MHPs, mental health professionals.

Shared reality

Empathising with experiences

Syrian MHPs lived through war and were forcibly displaced themselves and directly and indirectly experienced traumatic events. This enabled them to empathise with clients’ experience. All referred to this as an asset creating better understanding and trust within therapy.

…they have family who has been detained and I have family who is detained. Some have family who they have not seen for a long time and I too have not seen my family for a long time, because of the war… It lets you be more empathic, sometimes you be may be able to relieve him more…it makes you have more motivation, it makes you feel how much he is literally suffering. (P3)

A smaller proportion of MHPs gave examples of how sharing a traumatic reality led to unpleasant reminders, some preferring not to go into too much detail to avoid over-identification and emotional harm.

…a male patient, he was in prison and was subject to a lot of torture… I always heard about these things but I never thought I will see it in reality. It was hard for me because afterwards I thought that my brother [who was imprisoned and possibly killed in Syria] might have gone through the same things. (P1)

I do not go into a lot of details with [the client] about the problem, so as not to empathise to the extent that I feel that our problem is one. (P16)

Understanding language and culture

As well as having shared experiences, Syrian MHPs shared the language and culture of their clients. MHPs commented on how their nuanced understanding of Syrian dialects allows them to link a clients’ dialect to their cultural, religious, political and social contexts. Their understanding of cultural and religious norms and practices such as the male–female relationship in relation to disclosing emotional experiences, physical touch and using words of comfort appropriately according to a clients’ spiritual context was a useful tool.

We tried in our work to have females treat males but it did not work. This is in our culture, it is shameful for males to talk about his problems with females and this is why males prefer to talk with male doctor. So we started to refer males to males and females to us [females]. (P1)

So if [a client] says my son became a martyr, you don't just say ‘oh ok’ and write it down and then what… you make them feel that you heard them… and say oh Allah rest his soul, and Allah willing he's now in heaven and may his martyrdom be a reason for your redemption. (P3)

Self-disclosure

The majority of Syrian MHPs used self-disclosure as a tool in therapy with varied uses; to help clients see the MHP as an example of having overcome difficulties given their shared experience, or for political purposes to build the clients’ trust given the tensions and conflicts within in Syria, particularly if clients come from different areas. One MHP noted that:

…[most of my clients] are originally from rural Aleppo and they speak in a different accent as I come from Douma…Patients ask me where I am from. This question could come from the fear inside them that I have different political views or I might report them to the Syrian regime. In this case, I tell them that I am from Douma which they know that it has gone through the same experience as rural Aleppo. (P14)

All MHPs gave disclaimers regarding self-disclosure, either relating to professional boundaries, their psychological approach or their social context. MHPs were more likely to use disclosure to reduce perceived power imbalances:

…when he comes to see a therapist or doctor, he thinks that the therapist/doctor comes from another planet and doesn't know the struggle that he goes through. So we talk about general issues like there's a lot of traffic, public transport is expensive, rent is going up for us as Syrians, living in Turkey is expensive …he feels that you've experienced the same struggle… (P3)

MHPs spoke about the importance of the use of professional boundaries as a way to protect the client, themselves and the relationship using contracts, fixed hours of contact and placing responsibility onto clients.

Sometimes the relationship becomes unprofessional when I start to use the phone to call them and see how they are doing. When [I feel this] … I reduce the number of sessions and give her the responsibility to make her…life choices. (P10)

This is what made a difference - listening to stories made me stronger and now I was able to override this feeling [of being overwhelmed by traumatic stories] and have immunity and I put a separation between me and the client so that I don’t get affected. (P16)

Personal impact of therapy

Fulfilment

All MHPs spoke about how knowing that they have helped and relieved their clients was rewarding, and for some, this acted as a main motivator to help overcome the emotional difficulties of this work:

…the thing that protects me is to complete therapy [with a client] and see the improvement and change that happened. The person who came completely destroyed and began to love life… when you see the change…this is the biggest thing that pushes me through difficulties. (P16)

MHPs spoke about how their clients taught them things that enabled them to grow emotionally and that listening to difficult and traumatic stories over the years helped to make them more immune to distress as MHPs:

I used to tell my teacher I do not think I can treat people in the future because I lost my brother… she told me you will be able to do it because you are Syrian and you know Arabic and you will be a role model for those people who you will meet. Now [with time] I think this true because when I see Syrians who are struggling I can feel what they are going though. Jalaluddin Rumi said that the wound in your heart is the place where light enters you. (P1)

Most of the Syrian MHPs identified as Muslim and most also spoke about gaining spiritual satisfaction from helping others, with some saying that they felt their purpose was to be brought from the war to help others who are affected, and others saying they feel satisfied that God will reward them for their work.

Distress

As well as the fulfilling aspects of therapy, MHPs also spoke about the personal negative impact of clients’ traumatic stories, describing experiencing secondary traumatic stress and burnout:

At the beginning of my experience I was by myself with a lot of trauma cases I felt that I was burnt out…and that I was trapped. I was not happy, I started having nightmares because I was exposed to very big issues such as incest, physical and sexual assaults, losing body parts and suicide. (P1)

The other day I was working at the orphanage and I saw 11 people in one day…this is a big number and causes pressure, mental exhaustion and burnout. Sometimes you're tired and you need to take a day off…your capacity becomes less…and this is…we all…this is burnout. (P3)

To be honest, sometimes at the end of the day I feel that I am unable to speak anymore, around 5.30 when we finish our work. (P4)

MHPs also mentioned feeling shocked by the traumatic experiences that their clients endured. This shock often came with MHPs empathising and bearing witness to the reality that individuals experienced such atrocities, rather than seeing them as abstract events spoken about or reported in media outlets.

These were things…I only heard about and did not expect that it existed in reality and that I will see it in the real word. (P1)

I was shocked by what [the children] went through… (P10)

I used to think it’s unbelievable all this pain happened to us, I can’t believe to this extent; really is it possible that this shelling happened, these things happened inside prisons? (P16)

Ways of coping

All Syrian MHPs had their individual ways of coping with the emotional impact of therapy. All spoke about the importance of seeking support and increasing their knowledge through supervision, resources or peer support:

Peer support is also important, your colleagues around you, it is not the same as supervision, but it helps. (P8)

You need to work with the skills and the responsibilities that you have, rather than trying to do things you’re not qualified for…[K]eeping up with literature, Cochrane reviews and so on…I try to keep up to date. (P9)

MHPs also spoke about the importance of having support through friends or family to talk about their own difficulties:

Sometimes when I have problems in my life or with my son, it is hard to always listen to all people, sometimes it is a very simple thing but you feel you need someone to ask about you…you just need to talk to someone. (P4)

Six participants spoke about using personal therapy to cope with difficulties so that they can provide better care to their clients, despite this being stigmatised within the community and that this was often not spoken about:

Personal therapy is useful. First, it allows me to put myself in my patients’ position, this makes me feel humble. Second, it gives me the chance to explore the perspectives of other therapists and how they see things. Third, when there is an issue that is overwhelming, personal therapy gives me the space to speak out about it. (PA)

On the social level, people still have stigma about psychology…we don’t tell each other that we need help but we still go and seek the help. We still have the stigma about psychology treatment. (PA)

All participants spoke about self-care, often as spending time either with loved ones or alone without thinking or speaking about work and being around nature:

Gaziantep has a lot of big and beautiful gardens where we go and spend time, sometimes we meet friends, but also sometimes you feel you just want to be on your own. (P4)

My wife has started to follow my cases and understand my work. She says to me ‘where is the self-care?! You train on self-care but we want you to do self-care with us!’ [laughter] she’s like ‘Let’s go to the ocean this year’, so we will go with the kids. (P9)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to shed light on the experiences of forcibly displaced Syrian MHPs providing services to Syrians affected by conflict. This was a qualitative exploration of challenges faced by Syrian MHPs among the shortages of mental health provision, high case loads and emotional vulnerability in light of shared traumatic experiences with clients, while illuminating the satisfaction gained from providing therapy using multiple means of coping. The shared reality of practitioner and client enhances empathy and understanding and overcomes language and cultural barriers often present in these settings where there is a gap between the demand and supply of mental health services.

Published literature, particularly using quantitative methodology, tends to conceptualise positive and negative impacts of therapy provision as separate and mutually exclusive entities. However, a qualitative exploration of Sri Lankan MHPs working with Sri Lankan survivors of trauma described “an accumulated negative emotional impact but also to simultaneously contain positive, growth-promoting and personally satisfying aspects”.33 Another qualitative study of trauma therapists showed positive changes co-occurred alongside negative emotional impacts.34 These mirror this study’s findings, where fulfilment and distress emerged as parallel themes relating to the overarching theme of the personal impact of therapy. There is a need to further investigate the coexistence and interaction of the positive and negative impacts of therapy provision, particularly where there is a shared reality. The concept of a shared resilience in a traumatic reality goes some way in understanding this, yet this concept has not been addressed sufficiently.15

Syrian MHPs spoke about the shock of the human rights abuses inflicted on their clients by the Syrian government, including torture and sexual abuse, particularly early on in their working lives. This fits with broader qualitative research capturing shock as a theme experienced by counsellors in Sydney working in child protection services35 and child trauma therapists in America.36 Similarly, time and experience were key moderators of the negative emotional impact in both studies; more time and experience led to less distress and overwhelming emotions.

Previous research suggests that MHPs’ own difficult experiences may facilitate empathic connection with clients, and this may allow MHPs to be more aware of the thoughts and feelings that clients invoke within them, facilitating helpful reactions to client material.37 The shared reality of all Syrian MHPs facilitated empathy, enhancing their sense of compassion satisfaction and bonding, allowing them to feel more competent in helping their clients.20 This shared reality also enabled greater understanding of cultural nuances and language; an important strength given the lack of available sensitively trained interpreters and that matching MHPs to clients based on language similarities has been shown to predict better therapy outcomes.38

In some cases, clients’ war-related traumatic experiences reminded Syrian MHPs of their own experiences and some MHPs noted not going into too much detail about the clients’ distressing experiences to avoid overidentification. It is unclear whether or how this may affect the therapy process, particularly when processing or reliving trauma, as theoretical underpinnings of both EMDR and trauma focused cognitive behavioural therapy require clients to bring to mind and/or verbalise necessary detail. Shared realities led to challenges that this data may not have captured. Literature on ethnic minority therapists working with ethnic minority clients reveals challenges including therapist overidentification leading to assumptions and potential clashes in cultural values,39 the latter also likely challenges for Syrian MHPs working with Syrians residing in a Turkish majority country.

Syrian MHPs in this study reported using self-disclosure cautiously while maintaining professional boundaries, despite theory on shared trauma in a traumatic reality predicting greater self-disclosure, blurred boundaries and burnout.12 It is possible that adherence to professional boundaries, encouraged by training sessions that many Syrian MHPs received, contributed to protecting participants from the experience of burnout. Syrian MHPs in similar social and financial situations to their clients reported using disclosure as a way to gain common ground, in contrast to more privileged MHPs actively not disclosing. Previous research with cross-cultural dyads showed that therapist self-disclosure was only perceived as helpful when used as an ‘effective strategy for bridging perceived social and power distance’.40

Longitudinal research with INGO workers showed that social support was associated with lower levels of depression, burnout, lack of personal accomplishment and greater life satisfaction41; self-care among Syrian MHPs was often located in the context of social support. MHPs need to have insight into their feelings and the ability to differentiate between the needs of the self and of the client.42 A number of Syrian MHPs described personal therapy as a helpful means to do this and as a way to cope with emotional distress despite a stigma surrounding this. MHPs experience barriers to disclosure of undertaking personal therapy with negative consequences such as being seen as incompetent.23 Syrian MHPs seeking personal therapy are likely to experience double stigma given that mental health problems have been described among the Syrian community in this research as highly stigmatised, as well as within Arab communities overall.43

Syrian MHPs collectively experience the ongoing Syrian conflict on a daily basis through media outlets, while hearing first-hand accounts from clients, family and friends about the ongoing human rights violations committed in the context of the failure of the international community and law. This may damage their sense of hope, connection and faith in humanity. Maintaining optimism and hopefulness are essential aspects of being an effective trauma therapist.44 A number of Syrian MHPs’ strong sense of faith in God and their purpose was away to make sense of incomprehensive violations and to maintain hope. Spirituality also brought a sense of satisfaction to a number of participants and Syrian MHPs saw their work as a good deed towards a wider struggle and a wider cause.

The findings are subject to some limitations. Given that a large part of recruitment was through Trauma Aid’s channels, there may have been an unspoken message that the nature of their involvement would be linked to Trauma Aid, despite emphasis on the voluntary nature of their involvement and the separation of the interviewer and this research. Although a number of participants did discuss the challenges they faced, boundary violations and personal disclosure, this may have created more of a reluctance in openly discussing such topics. Furthermore, the information sheet and content of interviews may have led those who are struggling to understandably opt out, therefore creating a less representative sample and greater impression of coping. This research is a result of the interaction of a small research team, including a bilingual interviewer, with a specific group of displaced Syrian MHPs in the specific context of Turkey, and this should be considered regarding applicability of findings. However, the use of a transparent approach, credibility checks and emphasis on reflexivity throughout the process allows for replicability of the methodology with different groups and contexts. It would be worthwhile to extend this research to other contexts where Syrians are forcibly displaced, such as in Jordan, Lebanon, Germany and within Syria. Mental health provision is likely to differ in each of these contexts given the differences in the numbers of forcibly displaced Syrians, the majority language and culture of the country, the sociopolitical context and the available resources; further research could shed light on this.

The findings from this snapshot of Syrian MHPs may suggest that training local Syrians with a mental health background to provide therapy to Syrians within the community is a helpful way to promote understanding and empathy while reducing cultural and language barriers, as suggested by best practice in mental health and psychosocial support service provision guidelines.6–8 It is also a sustainable model of mental healthcare provision, in line with the United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Sustainable Development Goals.45 46 Over time, Syrian MHPs gain enough experience to become supervisors themselves, increasing access and resources to mental healthcare within displaced, conflict-affected communities. Given the international refugee crisis as a result of the Syrian conflict, Syrian MHPs are very well placed to support and advise other MHPs who work with Syrians. It would be worthwhile for Syrian MHPs to provide seminars, lectures, workshops and consultations on the provision of culturally appropriate and sensitive support for Syrians.

This model also creates the potential for emotional vulnerability in Syrian MHPs. It is important, then, to ensure adequate supervision where necessary, even if through online means, to enable MHPs to discuss difficult cases. Peer-support should be promoted and encouraged in the workplace within this community; this has been found to help prevent and manage secondary traumatic stress.47 Personal therapy should also be made available within organisations. Given the stigma of accessing therapy within Syrian MHPs and the small and well-connected Syrian MHP community in Turkey, it would be helpful to introduce an Arabic-speaking therapist (even if virtually), who is not a displaced Syrian MHP within this circle, to ensure confidentiality. Despite high case loads and pressure given reduced resources, increased emphasis and awareness of self-care is important, including promoting a work–life balance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Syrian mental health professionals who dedicated their time and knowledge to make this research possible and we would like to acknowledge Trauma Aid UK for facilitating this research.

Footnotes

Contributors: AH, ACdCW and KS designed and conceptualised the study. AH coordinated and carried out the data collection. AH analysed and interpreted the data. AH led manuscript writing with contributions from ACdCW and KS. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the UCL Doctorate in Clinical Psychology, funded by Camden & Islington NHS Foundation Trust. It was also supported by a UCL Grand Challenges grant.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study met the University College London Research Ethics Committee approved criteria (0163/001).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Amnesty International The worst humanitarian crisis of our time. Syria: Amnesty International, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Humanitarian Needs Overview: Syrian Arab Republic, 2017, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Physicians for Human Rights Anatomy of crisis: a map of attacks in health care in Syria. Available: http://syriamap.phr.org/#/en [Accessed 9 Mar 2019].

- 4.Footer KHA, Clouse E, Rayes D, et al. Qualitative accounts from Syrian health professionals regarding violations of the right to health, including the use of chemical weapons, in opposition-held Syria. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021096. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fouad FM, Sparrow A, Tarakji A, et al. Health workers and the weaponisation of health care in Syria: a preliminary inquiry for the Lancet-American University of Beirut Commission on Syria. Lancet 2017;390:2516–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30741-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization mhGAP humanitarian intervention guide (mhGAP-HIG): clinical management of mental neurological and substance use conditions in humanitarian emergencies. World Health Organization, 2015. https://www.who.int/mental_health/publications/mhgap_hig/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization,, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees . Assessment and management of conditions specifically related to stress: mhGAP intervention guide module. World Health Organization, 2013. https://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/mhgap_module_management_stress/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inter-Agency Standing Committee IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. IASC, 2007. Available: https://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/9781424334445/en/ [Accessed 10 Apr 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.El-Khani A, Cartwright K, Ang C, et al. Testing the feasibility of delivering and evaluating a child mental health recovery program enhanced with additional parenting sessions for families displaced by the Syrian conflict: a pilot study. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 2018;24:188–200. 10.1037/pac0000287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almoshmosh N, Mobayed M, Aljendi M. Mental health and psychosocial needs of Syrian refugees and the role of Syrian non-governmental organisations. BJPsych Int 2016;13:81–3. 10.1192/S2056474000001380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaghrout-Hodali M. Humanitarian work using EMDR in Palestine and the Arab world. J EMDR Prac Res 2014;8:248–51. 10.1891/1933-3196.8.4.248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baum N. Shared traumatic reality in communal disasters: toward a conceptualization. Psychotherapy 2010;47:249–59. 10.1037/a0019784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuttman-Shwartz O, Dekel R. Training students for a shared traumatic reality. Soc Work 2008;53:279–81. 10.1093/sw/53.3.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen K, Collens P. The impact of trauma work on trauma workers: a metasynthesis on vicarious trauma and vicarious posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2013;5:570–80. 10.1037/a0030388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuttman-Shwartz O. Shared resilience in a traumatic reality: a new concept for trauma workers exposed personally and professionally to collective disaster. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 2015;16:466–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harb C. The Arab region: cultures, values, and identities. in Handbook of Arab American psychology. Routledge, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan G, Ventevogel P, Jefee-Bahloul H, et al. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2016;25:129–41. 10.1017/S2045796016000044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill CE, Knox S. Self-Disclosure. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 2001;38:413–7. 10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baum N. Secondary traumatization in mental health professionals: a systematic review of gender findings. Trauma Violence Abuse 2016;17:221–35. 10.1177/1524838015584357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tosone C, Lee M, Bialkin L, et al. Shared trauma: group reflections on the September 11th disaster. Psychoanal. Soc Work 2003;10:57–77. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirmayer LJ. Asklepian dreams: the ethos of the wounded-healer in the clinical encounter. Transcult Psychiatry 2003;40:248–77. 10.1177/1363461503402007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller GD, Baldwin DC. The implications of the wounded healer paradigm for the use of self in therapy : Baldwin M, The use of self in therapy. 2nd ed New York: Haworth Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zerubavel N, Wright Margaret O'Dougherty. The dilemma of the wounded healer. Psychotherapy 2012;49:482–91. 10.1037/a0027824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saakvitne KW. Shared trauma: the therapist's increased vulnerability. Psychoanal Dialogues 2002;12:443–9. 10.1080/10481881209348678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tosone C, Nuttman-Shwartz O, Stephens T. Shared trauma: when the professional is personal. Clin Soc Work J 2012;40:231–9. 10.1007/s10615-012-0395-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018;52:1893–907. 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLeod J. Narrative and psychotherapy. Sage, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barker NC, Pistrang N, Elliott R. Foundations of qualitative methods. research methods in clinical psychology: an introduction for students and practitioners. Wiley, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.White M, White MK, Wijaya M, et al. Narrative means to therapeutic ends. WW Norton & Company, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elliott R, Fischer CT, Rennie DL. Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Br J Clin Psychol 1999;38:215–29. 10.1348/014466599162782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satkunanayagam K, Tunariu A, Tribe R. A qualitative exploration of mental health professionals' experience of working with survivors of trauma in Sri Lanka. Int J Cult Ment Health 2010;3:43–51. 10.1080/17542861003593336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrison RL, Westwood MJ. Preventing vicarious traumatization of mental health therapists: identifying protective practices. Psychotherapy 2009;46:203–19. 10.1037/a0016081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter SV, Schofield MJ. How counsellors cope with traumatized clients: personal, professional and organizational strategies. Int J Adv Counselling 2006;28:121–38. 10.1007/s10447-005-9003-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lonergan BA, O'Halloran MS, Crane SCM. The development of the trauma therapist: a qualitative study of the child therapist's perspectives and experiences. Brief Treat Crisis Interv 2004;4:353–66. 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gelso CJ, Hayes J. Countertransference and the therapist's inner experience: perils and possibilities. Routledge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu LT, et al. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. J Consult Clin Psychol 1991;59:533–40. 10.1037/0022-006X.59.4.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sue DW. Counseling the culturally different: theory and practice. John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang DF, Berk A. Making cross-racial therapy work: a phenomenological study of clients' experiences of cross-racial therapy. J Couns Psychol 2009;56:521–36. 10.1037/a0016905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopes Cardozo B, Gotway Crawford C, Eriksson C, et al. Psychological distress, depression, anxiety, and burnout among international humanitarian aid workers: a longitudinal study. PLoS One 2012;7:e44948. 10.1371/journal.pone.0044948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller L. Our own medicine: traumatized psychotherapists and the stresses of doing therapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 1998;35:137–46. 10.1037/h0087708 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aloud N, Rathur A. Factors affecting attitudes toward seeking and using formal mental health and psychological services among Arab Muslim populations. J Muslim Ment Health 2009;4:79–103. 10.1080/15564900802487675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearlman LA, Saakvitne KW. Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. WW Norton & Co, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.United Nations Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Izutsu T, Tsutsumi A, Minas H, et al. Mental health and wellbeing in the sustainable development goals. Lancet Psychiatry 2015;2:1052–4. 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00457-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rourke MT. Compassion fatigue in pediatric palliative care providers. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54:631–44. 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.