Abstract

Objective

To develop a multidimensional framework representing patients’ perspectives on comfort to guide practice and quality initiatives aimed at improving patients’ experiences of care.

Design

Two-stage qualitative descriptive study design. Findings from a previously published synthesis of 62 studies (stage 1) informed data collection and analysis of 25 semistructured interviews (stage 2) exploring patients’ perspectives of comfort in an acute care setting.

Setting

Cardiac surgical unit in New Zealand.

Participants

Culturally diverse patients in hospital undergoing heart surgery.

Main outcomes

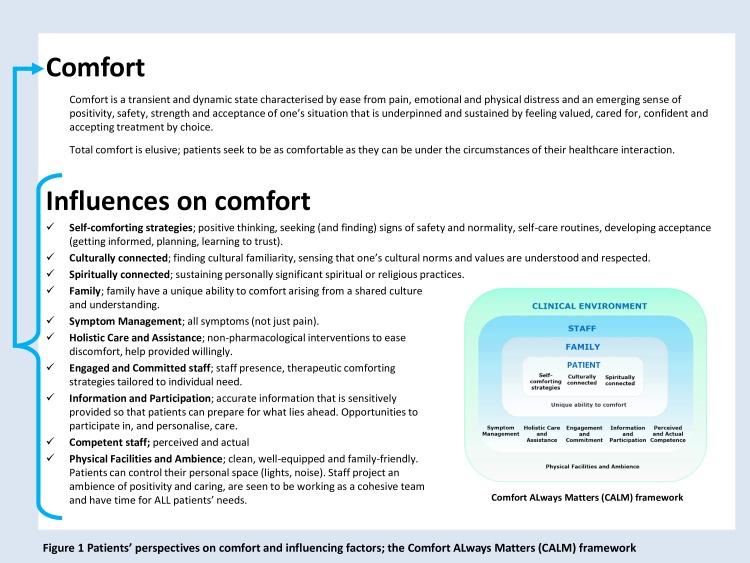

A definition of comfort. The Comfort ALways Matters (CALM) framework describing factors influencing comfort.

Results

Comfort is transient and multidimensional and, as defined by patients, incorporates more than the absence of pain. Factors influencing comfort were synthesised into 10 themes within four inter-related layers: patients’ personal (often private) strategies; the unique role of family; staff actions and behaviours; and factors within the clinical environment.

Conclusions

These findings provide new insights into what comfort means to patients, the care required to promote their comfort and the reasons for which doing so is important. We have developed a definition of comfort and the CALM framework, which can be used by healthcare leaders and clinicians to guide practice and quality initiatives aimed at maximising comfort and minimising distress. These findings appear applicable to a range of inpatient populations. A focus on comfort by individuals is crucial, but leadership will be essential for driving the changes needed to reduce unwarranted variability in care that affects comfort.

Keywords: comfort, patient experience, quality in health care, qualitative research, person and family centred care, compassion

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A comprehensive conceptual framework developed from an integrative review of 62 studies (14 theoretical and 48 qualitative) focused the exploration of patients’ perspectives on comfort in an acute care setting.

The definition of comfort (the state) and description of influencing factors (processes of care) were developed using qualitative methods aimed at understanding how comfort and comforting is perceived and experienced by patients.

The study reported on here is the first that has set out to explore a cultural dimension of comfort via purposive sampling of culturally diverse patients.

Peer debriefing, Māori and Pacific consultation, prolonged engagement, negative case analysis and triangulation promote credibility.

The two-stage approach enabled development (stage 1) and then refinement (stage 2) of themes and operational definitions that capture the broad influences on comfort in one unifying framework. However, identifying context-specific detail is required for application.

Introduction

Championing patients’ need for comfort was central to the origins of person-centred care organisations such as the Picker Institute1 and Planetree.2 Within the executive summary of the Institute of Medicine’s landmark report ‘To Err is Human’ is stated, ‘it is not acceptable for patients to be harmed by the health care system that is supposed to offer healing and comfort’ 3 (p. 3). Hippocrates’ quote ‘To cure sometimes, to relieve often, to comfort always’ is familiar to many. More recently, the 2012 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Patient Experience Guideline identified ‘comfort’ as one of seven outcomes of a good patient experience.4 Informed by the work of Gerteis and colleagues,5 promoting physical comfort became a core aspect of person-centred care frameworks.4 6 7 Comfort is also regarded as holistic and multidimensional,8–12 associated with concepts that are hallmarks of a caring and humane society such as dignity, empathy, kindness and compassion.13–15 This notion of comfort fits with evidence provided by patients and family during the Mid-Staffordshire Inquiry16 where good—and bad—care was described in terms of comfort, discomfort, comforting or feeling/looking uncomfortable. As such, comfort, or lack of it, is a defining aspect of patients’ experiences and an indication of the overall quality and safety of care. A service that fails to provide high-quality care that includes the promotion of comfort, or recognise avoidable suffering as a source of harm, means that patients and their family have been let down by those who are meant to care for them.3 16–22 Overall, reducing unwarranted variability in care important for comfort is a crucial aspect of quality person-centred care in contemporary healthcare settings.

But what is comfort, and what care matters to patients? Differing definitions8 10 11 23 and perspectives on comfort depicted in person-centred frameworks6 7 and concept analyses8–12 highlight that this concept is poorly defined for practice and quality improvement. In particular, the absence of a framework incorporating all that is relevant from patients’ perspectives24 risks provider-centric improvement that fails to deliver the care that matters. The purpose of this research was to develop a multidimensional framework representing patients’ perspectives on comfort that can be applied in a range of healthcare settings to guide practice and quality improvement initiatives aimed at improving patients’ experiences of care.

Method

A two-stage qualitative descriptive study design25 was used to explore patients’ perspectives on comfort and its influencing factors. This design is known for producing ‘findings closer to the data’25 (p. 78) and was considered appropriate for generating findings that could be translated into practice. In stage 1, data from 62 studies exploring the concept of comfort in healthcare settings were synthesised into a conceptual framework representing patients’ perspectives on comfort.24 Integrative review methods facilitated identification of multiple dimensions of comfort that appeared relevant. This framework informed the study reported here, which explored the concept of comfort in patients undergoing heart surgery. Heart surgery can be physically and emotionally distressing,26 therefore exploring patients’ perspectives on comfort and comforting care in a cardiac surgical setting was ideal. In summary, our two-stage approach enabled development (stage 1) and then refinement (stage 2) of a framework representing patients’ perspectives on factors influencing comfort.

Patient and public involvement

We used an exploratory method of data collection to better understand patients’ perspectives and experiences of care. Questions were informed by a conceptual framework developed from studies also exploring patients’ perspectives. Patients were not directly involved in the design of this research. However, cultural advisors provided advice that facilitated Māori and Pacific recruitment, led to refinements of the interview procedure and supported accurate representation of Māori and Pacific worldviews. The acceptability of the interview process and questions were tested in five pilot interviews involving patients of Māori, Pacific and New Zealand European (NZE) ethnicities. As part of the informed consent process, participating patients were offered the opportunity to review their interview transcript and feedback on its accuracy via a prepaid postage return of the hard copy or follow-up phone call. Presentations of the findings have been made in order for our results to benefit future patients and to guide research aimed at improving patient experience.

Site and setting

The study was conducted in a 47-bed cardiac surgical unit in a publicly funded hospital in Auckland, New Zealand.

Participant selection

Purposive sampling was used to access and invite participation from culturally diverse patients. Sampling aimed for one-third each of Māori (the tangata whenua or indigenous people of Aotearoa/New Zealand), NZE and Pacific people (people who migrated from, or who identify with, the Pacific Islands) to enable exploration of a cultural dimension of comfort. Inclusion criteria were: postoperative day 4 or 5 after operations classified as coronary artery bypass graft or valve replacement/repair; age 16 years or older; English speaking; transferred from the intensive care unit postoperative day 1; an expectation of discharge at or before eight postoperative days; sedation score of 0 (awake and alert) or 1 (mild sedation and easy to rouse); and ability to provide consent. Participants were identified in consultation with a senior nurse and then invited to participate by one researcher (CW) who emphasised her non-employee status. Informed consent was obtained. One experienced researcher (CW) conducted all interviews. Data saturation was sought regarding understanding how perspectives on comfort differed by ethnicity.

Data collection

Semistructured patient interviews explored: (1) what comfort meant to patients from which a definition of comfort was to be developed and (2) factors within the care setting that influenced comfort, that is, what care mattered to patients. Questions exploring influencing factors were informed by the conceptual framework24 (see online supplementary file 1, patient interview guide). Patients were not asked directly if the broad influences identified a priori were important for comfort. Pilot testing indicated this approach risked bias towards affirmative responses and less nuanced data. Rather, patients were asked about aspects of care related to conceptual framework themes, and responses were probed to determine the influences on comfort. Negative case analysis (searching for disconfirming evidence) was used throughout data collection and analysis.27 The final interview question gave participants the opportunity to describe influences on comfort that may have been missed. Interview settings were patients’ single rooms (n=7), a quiet room on the ward (n=13) or patients’ four-bedded room (n=5) the latter being participants’ preference. Interview durations were between 23 and 66 min (average 43 min) and similar between ethnicities (see online supplementary file 2, characteristics of patients). Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Participants were sent a copy of their interview transcript and given the opportunity to comment on accuracy and content.

bmjopen-2019-033336supp001.pdf (170KB, pdf)

Data analysis

Analysis was sequential. General inductive method28 was used to analyse data contributing to a definition of comfort. Inductive analysis gave some assurance that the definition of comfort was data derived and developed without undue researcher influence.28 29 Analysis involved: close reading of the transcribed text; creation of specific and then general (higher level) categories from patients’ description of comfort or derivatives of the word comfort (comforting, comfortable, uncomfortable and discomfort); and revision and refinement until four overall categories capturing the essence of what comfort feels like to patients were identified. Categories were summarised into a definition of comfort.

Thematic analysis29 and Framework method30 were used to analyse data related to influences on comfort using both deductive and inductive analysis. Deductive analysis tested the relevance of the conceptual framework to patients’ perspectives. Inductive analysis was important for enabling us to identify any new themes29 30 within patient interview data. The steps involved were:

Familiarisation with the transcribed texts. The definition of comfort was used to identify and begin coding patient interview data relevant to influences on comfort. Familiarisation involved careful consideration of the overall ‘fit’ of that data to the conceptual framework themes.24

Constructing an initial thematic framework from the conceptual framework headings24 building in themes and subthemes identified within the coded data. Some codes were derived from theme definitions developed a priori,24 while other codes were developed inductively from the data.

Indexing and sorting, in which data were systematically sorted into the thematic framework.

Reviewing data extracts, checking for coherence between codes and refining the thematic framework accordingly.

Data summary and display; matrices of distilled coded text were developed for each subtheme to enable data to be easily compared between participants and between ethnic groups.

Abstraction and interpretation of the data; multiple and inter-related factors influencing patient comfort were identified. A careful comparison between stage 124 and stage 2 findings was made to determine transferability beyond the cardiac surgical setting.31

Data were managed using NVivo Version 10 software. One researcher (CW) coded all data. Coding decisions were discussed at regularly scheduled meetings (MB, AM, CW). Peer debriefing27 occurred throughout all stages of data analysis. Discussion and refinement of themes and subthemes occurred until consensus was reached. Consultation with Māori and Pacific healthcare staff ensured that the recruitment process, interview procedure and data analysis promoted participation of Māori and Pacific patients and accurate representation of their worldview. We used the SRQR checklist when writing our report.32

Results

Twenty-five participants were interviewed on either day 4 (72%) or day 5 (28%) after surgery. Eight patients self-identified as Māori, 7 as Pacific people and 10 as NZE. Median age was 63 years (range 30–85) and 64% were men. Fourteen patients underwent coronary artery bypass graft, 10 underwent valve replacement/repair (n=10) and 1 patient underwent both (online supplementary file 2). Fifteen patients declined participation for reasons outlined in online supplementary file 3.

Comfort: a universal concept

Perspectives on comfort reported by patients in primary studies24 were similar to those held by patients undergoing heart surgery. As such, comfort is regarded as having universal relevance, and the findings presented here appear applicable to a range of inpatient populations.

Patients’ perspectives on comfort

Patients’ perspectives on comfort are summarised in the following definition:

Comfort is a transient and dynamic state characterised by ease from pain, emotional and physical distress and an emerging sense of positivity, safety, strength and acceptance of one’s situation that is underpinned and sustained by feeling valued, cared for, confident and accepting treatment by choice. Total comfort is elusive; rather, patients seek to be as comfortable as they can be under the circumstances of their healthcare interaction.

Underpinning our definition are the following four senses of comfort that were identified in the patient interview data:

‘Relief (ease) from pain, emotional and physical distress’.

‘Feeling positive, safe and stronger’.

‘Feeling confident, in control, accepting treatment and care by choice’.

‘Feeling cared for, valued; connecting positively to people and place’.

When is comforting care important?

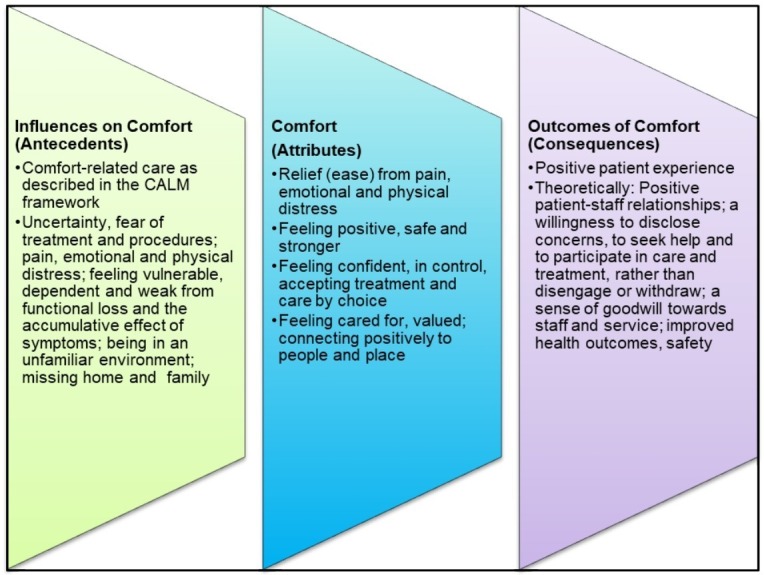

Patients’ need for comforting care varied between individuals and could occur at any stage of the healthcare interaction. Common triggers were: the uncertainty and fear of treatment and planned procedures; pain, emotional and physical distress; feeling vulnerable, dependent and weak from functional loss and the accumulative effect of multiple symptoms; being in an unfamiliar environment; and missing home and family.

Factors influencing patients’ comfort

Factors influencing comfort were complex but underpinned by 10 themes, as depicted in the conceptual framework that we had named the Comfort ALways Matters (CALM) framework24 (see figure 1). Themes occurred within four integrated layers: patients’ personal strategies; the role of family; staff actions and behaviours; and factors within the clinical environment. The broad themes identified in stage 1 were consistent with those identified by patients undergoing heart surgery. Most theme names were retained. However, patient interview data led to a deeper, more nuanced understanding of these themes. Accordingly, the theme definitions presented here have been refined to better reflect: (1) the care that matters to patients, (2) the integrated nature of that care and (3) aspects of culturally responsive care that had not been previously identified. The theme related to family influences was renamed to reflect important ethnocultural differences in the way family comfort. The essence of each theme and their unified influence on patients’ sense of comfort is portrayed in figure 1. Operational definitions, subthemes and illustrative quotes for all themes are provided in tables 1–4. Themes within each layer are now discussed.

Figure 1.

Patients’ perspectives on comfort and influencing factors; the comfort always matters (CALM) framework.

Table 1.

Patients’ personal (often private) strategies

| Influence | Operational definition | Subthemes and supporting evidence*† |

| Self-comforting strategies | During times of distress and uncertainty, patients work to maintain a sense of comfort using personal strategies that include positive thinking, looking for reassuring signs of safety and normality through surveillance of self and others, self-care routines, getting informed, planning and learning to trust. The success of these strategies is moderated by patient characteristics and influences from family, staff, other patients and the clinical environment. Some patients may use withdrawal (disengagement from staff and service) or at least thoughts of doing so, as a strategy to promote short-term but potentially self-harming relief from discomfort and distress. |

The operational definition for the theme ‘Self-comforting strategies’ was generated from data coded to four subthemes: ‘Maintaining positivity and strength’ Positive thinking helped patients stay positive and mentally strong when faced with fear and uncertainty of personally challenging treatment and care. Examples include celebrating small milestones during postoperative recovery and focusing on the benefits of surgery rather than the risks. ’I just kept on saying to myself I’m part of the majority [who survive], that kept me going because I was going to walk straight out’ (P5). ‘Safety through surveillance of self and others’ Patients sought to reassure themselves of their safety through surveillance of their own symptoms and surveillance of staff. Not being able to rationalise symptoms as ‘normal’ (NZE8) could cause significant distress. Conversely, patients drew comfort from the knowledge that symptoms or odd sensations were to be expected under the circumstances. ‘I just told myself it was something from the surgery you know I knew exactly what it was’ (NZE7). Observing that staff were watchful and checking on them ‘when they’re supposed to’ (NZE7) also provided reassurance of safety. ‘They’ll pop their head in when it’s not their time to see how you are. I know, I keep an eye on their schedules’ (M1). ‘Strategies to develop a sense of ease’ Distraction (watching TV, listening to music and seeking out people to chat with) eased emotional discomfort by helping patients take their mind off unpleasant or unsettling events. ‘I didn’t like being in a separate room, I didn’t like that … I felt quite isolated. I mean I’m a bit of a chatty person, not everybody likes to talk but you know you like to know the people around’ (NZE4). Self-care routines (mindfulness and meditation), pulling curtains for privacy, making the effort to connect with one’s roommates temporarily eased discomfort associated with disturbing factors within the hospital environment (such as noise and room sharing with strangers). ‘I’ll just go into the room and I tend to pull the curtains across, I’ve got an iPod there, I usually listen to a bit of music’ (NZE2). Some patients used withdrawal and disengagement to ease discomfort and distress. Examples included withdrawing from interactions with staff, with other patients, contemplating not going through with the surgery, or self (early) discharge after surgery. ‘I was a bit emotional before the operation … I was crying, I want to go home, I want to go home’ (NZE6). ‘They say oh I’ll be back in five min and they’re gone. And then ring the bell, ring the bell, that’s why I said to my daughter I’m ready to go home’ (P1). ’Strategies promoting acceptance’ Underpinning a sense of comfort was developing acceptance of one’s situation using strategies that included use of humour, getting informed (reading and asking questions), developing some sort of plan or way forward for situations causing concern and focusing on the necessity of unpleasant treatments, surgery, lifestyle changes and so forth. ‘[I was] quite chirpy and cheeky to the (theatre) nurses just to try and keep myself cool, you know, just to cool myself down and get ready to accept the inevitable, you know’ (M8). Patients also gained comfort by developing a sense of trust in either the process or the people around them. Trust was integral to feeling able to accept care and treatment by choice. ‘I don’t ask much because I haven’t been concerned about anything really. I trust them. My first operation really gave me the trust you know, people that trained years to be there, you’ve got to trust them’ (M7). |

| Culturally connected | Patients find it hard to be fully comfortable in hospital because they miss home, family and invariably encounter cultural norms, values and practices that may be different to their own. Comfort is enhanced in an environment that patients perceive to be welcoming to them and their family, culturally familiar and there is the sense that others (staff, other patients) understand and respect their cultural norms and values. These perceptions help patients develop a sense of comfort related to connecting positively with people and place without tension or the need to repress personally important values, beliefs and preferences for care. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Culturally connected’ was generated from data coded to three subthemes. The first two subthemes provide the context for a cultural dimension of comfort, the third indicates the importance of staff competence in culturally safe care. ‘Missing home and family - hospital as a culturally unfamiliar environment’ Patients described the discomfort of needing to live—although temporarily—in an environment patients variously described as ‘alien’, ‘foreign’ and very ‘different’ to home. Different things were missed by different people but, overall, unfamiliar routines, certain expectations of behaviour and missing home life exacerbated patients’ sense of unease associated with being in the healthcare setting. ‘… I’ve had my brother in law and his children come up and his kids are like my grandkids you know, full of life. The doctors say keep quiet, and I keep quiet and let them make the noise. I love the children …’ (M4). ‘…I just couldn’t go anywhere and feel that you were finally away in your own private little area that you could just chill out in with your family and things like that. So that’s pretty hard, you’re just trapped’ (NZE2). ‘I miss my kids and my husband and my grandchildren. It’s the love that you have at home. It’s your privacy your own privacy at home’ (P1). ‘Culturally important values and care preferences’ All patients held important values and care preferences related to, for example, meaning of family (who should visit and expected visitor behaviour); room sharing; communication styles and deference to hospital rules; attitudes around treatment regimens, putting up with pain and body modesty; expectations of caring (notion of service and being treated like family), food preferences and spiritual beliefs (use of prayer/karakia). Underlying tensions associated with cultural differences were evident. For example, perspectives may differ between patients, staff and other visiting families about who should visit and acceptable visitor behaviour. ‘It’s what Pacific Islanders do. We all have the same sort of morals…They [visitors] just come to show their support, respect and love, yeah’ (P7). ’Feeling welcome, connecting positively with others amidst cultural differences’ Crucial to comfort (feeling at ease, safe and positive connections) was patients’ sense of welcome and that others (staff and other patients) understood and accepted culturally important values and care preferences. Patients sought signs of welcome, of respect and of cultural acceptance. Examples include observing culturally diverse staff working as a team, the quality of communication between staff and other patients (‘no racism here’ M4), family being able to visit or share karakia outside of visiting hours, availability of cultural support staff and culturally diverse décor. ‘… [I]t was a lot easier within our room because we were Māori, we understood. Like one whanau [family] came in first and I said kei te pai (good, that’s fine) you fellows have your time … They felt like they were taking up too much space’ (M3). Attitudes, treatment regimens, rules and routines not congruent with one’s personal values (eg, differing interpretations of body modesty, expectations of service and care) or based on a stereotypical understanding of cultural preferences undermined patients’ sense of welcome and could distress. ‘[S]ometimes they leave you there naked (under a sheet) you know, and you can’t do anything’ (P1). |

| Spiritually connected | Some patients gain a sense of comfort from feeling connected to a higher power and sustaining that connection through personally significant spiritual or religious practices. Patients’ need for spiritual comfort may be intensely private and not always related to strongly held religious or spiritual beliefs. The need for spiritual comfort is dynamic, intensifying during times of distress or uncertainty. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Spiritually connected’ was generated from data summarised in two subthemes: ’In God’s Hands’ During times of uncertainty, some patients gained a sense of comfort (feeling safe, strengthened and at ease) through their trust in God, believing that ‘God would do the right thing’ (NZE6) and events were ‘part of God’s plan… no doubt, no fear’ (M4). ‘I pray for them [staff], when I went in to the operation and the nurses going to take care of me in there. …When you put your trust in the Lord He will come then, show them the way’ (P1). To those of no spiritual or religious affiliations, the idea of putting one’s faith in a higher power neither provided nor detracted from their comfort. ‘… I can understand people being of faith probably being comforted by the fact that they think someone’s out there looking after them but I’ve never gone with that… (NZE2). ’Sustaining spiritually important practices, connecting with God’ Staying connected to (sometimes re-establishing) one’s faith provided comfort during times of distress. ‘… [A]ll the time I feel pain God helped me…I am very close to God when I’m sick, when I’m okay I run around and do everything I want and I forgot. I only remember Him when I’m sick…’ (P4). Not being able to sustain important spiritual values and practice could be distressing, for example, if food options or treatment regimens conflicted with spiritual beliefs, or if there was no space for sharing prayer (karakia) with family. Family, Kaumātua (Māori elder held in high esteem) and chaplains helped sustain spiritually important connections. ‘I asked for a Kaumātua … could he say something (a karakia before surgery) for me. And I was happy. I was happy what he said to me, what he did to me. I’m happy about it’ (M6). |

* Patient interviews were coded by ethnicity and interview order, that is, M1 is the first Māori interview, P1 for the first Pacific interview and NZE1 is the first New Zealand European (NZE) interview.

†Examples are from stage 2 semistructured interviews of patients undergoing heart surgery.

NZE, New Zealand European.

Table 2.

Family influences on comfort

| Influence | Operational definition | Subthemes and supporting evidence*† |

| Family’s unique ability to comfort | Familiarity gives family the unique ability to comfort that complements care provided by staff. From most patients’ perspectives, having loved ones near, connecting with those who know them best and whom they trust, promotes positivity and acceptance of care and provides an important buffer to the unfamiliarity and uncertainty of the clinical environment. Family also comfort through the provision of holistic care and practical support. Patients do not readily relinquish their family role and responsibilities even when facing personal health challenges. Under these circumstances, family-friendly facilities and positive family–staff relationships offset patients’ sense of discomfort about the impact their situation may be having on others. These factors also facilitate family’s ability to comfort. Conflicting views between family and clinical staff can exacerbate doubt in treatment and care among those already feeling vulnerable or uncertain; the most comforting scenario for patients is that family and staff views align. How family is defined and the nature of comforting activities need to be seen in the context of what is culturally important for patients and their family. |

The operational definition for the theme ‘Unique ability to comfort’ was generated from data summarised in three subthemes: ‘You always want to see your family – comfort from someone who knows you’ The unique relationship between patient and family underpins family’s ability to comfort. Loved ones can be a buffer to the unfamiliar healthcare setting and a constant comforting presence during times of illness and uncertainty. Patients spoke of hospital life as ‘100% worse without your partner’ (NZE2), the comfort of having someone ‘hold my hand’ (NZE4) and someone ‘to touch’ (M7). ‘… it doesn’t matter how good the nurses, or the doctors are I always want to see my wife or my daughter…I know you give us a lot of helping hands but, in your mind, you always want to see your family.’ (P4). Family also help patients feel safer and more confident about treatment and care decisions. ‘My uncle came and just had a good word to me and sort of put me on track, he sort of made me feel better too you know …he was just more positive you know, like you’re going to be better, have a better life, you’re going to have a longer life … if I didn’t have no family I would have taken off’ (P7). ‘Comfort through practical support and care’ Family provide holistic and practical care that promoted comfort. Examples include back and shoulder rubs, bringing in culturally preferred food, helping with and advocating for care promoting physical comfort (position changes and pain relief). Family also provided practical support that eased patients’ concerns over impending discharge, lifestyle changes and how they would manage at home. ‘I’ve noticed the doctors and nurses take the time to explain things to her [wife] as well as to me which is good. They can probably see I look really spaced out its better to talk to her’ (NZE5). ‘Discomfort, unease related to family’ Even during personal distress, patients did not readily relinquish family roles and responsibilities (as grandmother, mother, father, partner, husband, daughter, family matriarch and so forth). Patients’ concern for their family’s safety and well-being, worry over being a ‘burden’ or ‘scaring’ family sometimes meant denying themselves the comfort of family visits. ‘… My daughter, she’s got her three little children and I don't want her to take them around, I don't want them to get in the car accident, it’s too far for them … I told them not to come back … I’d rather they were safe at home…’ (P2). Strained family relationships or family who did not understand patients’ needs added a layer of distress additional to that arising from their clinical condition. Similarly, differing views between family and staff could undermine patients’ confidence in treatment and care and may require them to make an uncomfortable choice between family and clinical staff recommendations. ‘I don't want to deal with her [wife]. I want to concentrate on the nurses and the doctors… ’ (P6). |

* Patient interviews were coded by ethnicity and interview order, that is, M1 is the first Māori interview, P1 for the first Pacific interview and NZE1 is the first New Zealand European (NZE) interview.

†Examples are from stage 2 semistructured interviews of patients undergoing heart surgery.

NZE, New Zealand European.

Table 3.

Staff influences on comfort

| Influence | Operational definition | Subthemes and supporting evidence*† |

| Symptom management |

Patients experience a range of distressing symptoms for which effective and sustained relief is crucial for their comfort. Symptom trajectories vary between patients; therefore, individualised assessment and treatment is essential. From patients’ perspectives, staff actions that promote effective symptom management include routinely asking about symptoms, taking patients’ symptoms seriously, pre-emptive or prompt treatment and working with patients to understand barriers to reporting symptoms and accepting treatment. When there are few effective pharmacological options, patient comfort becomes more dependent on other influencing factors such as holistic care and assistance. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Symptom Management’ summarises the findings from two underlying subthemes: ‘Variation in experience of common postoperative symptoms’ Patients’ symptom experience varied in terms of symptom presence, severity and trajectory. Physical and associated emotional discomfort commonly arose from pain. ‘I was in a lot of pain. I couldn’t move. I was really in agony. I couldn’t put my legs flat so I remember clearly having my legs up and if I got them up to a certain point it was just very slightly less painful than anywhere else. You know I remember just lying like that holding my knees because it was the best I could do’ (NZE5). Other distressing symptoms were postoperative nausea (‘… it’s killing me…’ (P2)), fatigue, inability to sleep, loss of appetite, shortness of breath, constipation, low mood, or depression, dreams, hallucinations and visual disturbance, taste disturbance, palpitations, and fluid retention. ‘It’s a very simple thing but it was upsetting, my fingers they were swollen twice the size …it was horrible’ (NZE4). ‘Complexity of effective symptom management’: Complex patient and contextual barriers to effective symptom management were identified. Barriers related to patients’ motivation for reporting symptoms, patients’ beliefs and preferences for treatment regimens, staff competence, underlying attitudes of staff and patients (such as to opioids and sleeping tablets), conflicting opinions on effective treatment, clinical jargon and the ability to personalise care. Patients emphasised the importance of participation in symptom management decisions and of feeling heard. Not feeling listened to or believed about the extent of symptom distress, prolonged physical distress and was emotionally upsetting. ‘I think because I’m big you know I don’t show the full soreness of my body …maybe they think I might be lying or something … I think they thought they were giving me too much painkillers … they were just saying we’re giving as much as we can … they were trying to find the best one for me but weren’t actually asking me which one was the best you know…’ (P7). Regular and competent symptom assessment followed by titrated symptom relief was essential for the duration of the admission. Pre-emptive symptom management and regularly offering analgesics were also important. Overall, symptom management depended on competent application of evidence-based symptom management protocols and on staff working with patients to understand and address barriers to reporting symptoms and accepting treatment (refer ‘Engagement and Commitment’ and ‘Information and Participation’). Other comforting actions become crucial when there were few effective strategies to combat distressing symptoms. These included support from family, empathetic and holistic care, reassurance about ‘normality’ and expected trajectory (refer family’s unique ability to comfort, holistic care and assistance, information and participation). |

| Holistic care and assistance | Patients experience significant physical and emotional discomfort from the accumulative effect of symptoms, treatment side effects, unpleasant procedures and loss of functional ability. Holistic care involving multiple, non-pharmacological interventions for relieving physical and emotional discomfort is essential and complements efforts to promote comfort through pharmacological symptom management. Assistance provided willingly reduces the substantial emotional and physical impact of loss of function and is an essential aspect of comforting. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Holistic Care and Assistance’ summarises the findings from three underlying subthemes, the first of which provides context for this theme. ‘Physical and emotional discomfort and distress’ Adding to patients’ symptom distress was an accumulation of factors that included treatment side effects (such as dry mouth and itchy skin), unpleasant treatments and procedures (a ‘cocktail’ of pills, venepuncture, echocardiogram, intravenous lines, oxygen therapy and blood pressure monitoring) and restricted mobility (from surgery and from being attached to equipment). ‘I had two days of pure hell, I just felt like I’d been run over by a truck. But there was no pain from the actual surgery it was all of the drugs that they had pumped through me, yeah, I had no energy to get up, no life. There was no life to push to get up’ (M3). Patients had limited ability to self-care, needing assistance getting out of bed, to the toilet, with hygiene, after vomiting or if they ‘made a mess in the toilet’; even pouring a drink of water could not be done without help. ‘I’ve felt like, [I have] been being run over by a bus and then backed over again, I feel terrible. You can’t even take your hands off the table to butter some bread. You just are so out of it, it’s such an awful feeling’ (M2). Worry about finances, returning to work, managing after discharge also contributed to emotional distress. ‘Treating the whole person, not discrete symptoms’: Complementing pharmacological symptom management was holistic assessment and care. ‘[the nurse] asked me really nicely and politely how I was, was this happening or is this happening, have I got any of this … you felt that somebody cared for sure which was, the other guys were saying that too’ (NZE7). Holistic interventions specific to heart surgery included being taught to use a ‘cough pillow’ and providing larger patients with a chest binder to prevent strain on the chest wound. Other interventions were a cooling fan, ice to suck, swift removal of drains, urinary catheters and intravenous lines, shower for itchy skin and positioning. ‘… [W]hen the nurse came in I told her it was getting a bit sore around the back and shoulder blade and she says, get your bum back in that bed, she gets my pillow and straightens them up and, ‘lie there now’ so I lay back down and oh yeah she knows what she’s talking about alright. It felt a hell of a lot better’ (M8). ‘Getting the help needed’ Getting help with personal care and basic tasks was crucial for a sense of comfort (feeling cared for and safe). However, patients felt unprepared for how reliant they would be on nursing staff. Adjusting to dependency was difficult and some were reluctant to ask for help for reasons that included worry about being ‘demanding’ (NZE4) and feeling uncomfortable asking for help with ‘basic bodily things’ (NZE9). Observing staff readily and ‘graciously’ (NZE10) providing help relieved a sense of unease about asking for, and accepting, the help needed. ‘… I didn’t realise that we’d have to be dependent on the nurses as much. I think I thought I could just get up and go, no it was far from it … they’ve been tremendous you know … it’s an eye opener’ (NZE10). Overall, comfort from holistic care and assistance was enhanced when delivered by staff with comforting staff qualities (refer ‘Engagement and Commitment’). Experiencing such care sets the tone for positive patient–staff relationships and satisfaction with the service. ‘I trust them. That’s their work to give life back to people that’s their work. Very hard work, but they never turn their back they try to do their work thoroughly. That’s how I believe them’ (P4). ‘… [P]eople going to hospital, they always talk about the nurses and I basically said it was absolutely true. You know they’re the front-line staff and the ones you deal with every day and they’re all amazing’ (NZE2). Conversely, a failure of staff to appear caring, helpful and responsive to one’s needs harboured resentment and made patients wary of future engagement with that staff member. ‘She didn’t seem to be caring enough, yeah. I woke up having a bad dream and asked her to get me a flannel, which they don’t even ask, can I?, I didn’t have any bedclothes on because I was so hot but they don’t even ask if they can put bedclothes on you know and so it’s little things like that, you know. [How does that affect you]. I think it affects me in the way that when I ring the bell I hope she doesn’t come you know. She was on nights and I was thinking gosh I hope that lady don’t come again’ (M2). |

| Staff engagement and commitment | Knowing that staff (all roles) are watchful and available when needed is fundamental to a sense of comfort. Patients’ comfort is also enhanced when staff make an effort to connect (are welcoming and friendly), when they promote positivity through reassurance and encouragement, are considerate and responsive to patients’ needs and when they demonstrate understanding of patients’ discomfort (distress, uncertainty and vulnerability) using therapeutic strategies tailored to individual need. Strategies include empathetic listening, taking time to explain, comforting touch, careful use of humour/chit chat, maintaining privacy, dignity and a respectful and caring manner during interactions. Being cared for in this way is foundational to a positive patient experience and appears to have therapeutic importance by promoting positive patient–staff relationships and a willingness to engage with staff, the service and health promoting behaviour in general. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Engagement and Commitment’ summarises the findings from three underlying subthemes. ‘Comforting staff presence – layers of surveillance and availability’ Patients’ perceptions that staff are present and available to them promotes emotional comfort associated with feeling safe and cared for. A comforting staff presence consisted of three layers: perception of 24 hours nursing presence; contact with doctors via ward or pain rounds, even if brief; and knowing that staff were available should they be needed. ‘… [S]he [primary nurse] might be attending another person but if she is normally it’s – ‘can you wait?’ but you know they’re going to come’ (NZE8). ‘Comforting staff qualities’ Staff qualities described as comforting were summarised as:

‘Therapeutic comforting strategies tailored to patients’ individual needs’ Comforting staff were those who combined comforting qualities with individualised strategies in a way that was foundational to a positive patient experience and promoted goodwill towards the staff (and service) that has supported them through a physically and emotionally challenging time. ‘I think they have done all, their faces, smiling faces, that will do. There’s a good treatment, here’ (P4). Comforting staff behaviour also had therapeutic importance by promoting patients’ willingness to disclose concerns, participation in care and treatment, and positive patient–staff relationships. Conversely, patients disengaged from staff with whom they did not connect, some even considering (early) self-discharge when they felt uncared for or disregarded. Comforting strategies tailored to patient’s unique needs included:

|

| Information and Participation | Information promotes comfort by reducing the distress of uncertainty and enables patients to prepare for and accept what lies ahead. Information also comforts by promoting trust and confidence in staff and the care provided. However, informing patients is an art and science; to comfort (and not distress), information needs to be provided by staff knowledgeable in the topic and sensitive to patients’ situation and personal preference for detail. Individualised care is essential for patients’ emotional and physical comfort. Patients who are accurately informed about when, why and how to report symptoms, who feel comfortable with staff and perceive them to be concerned for their welfare are more inclined to seek help, report symptoms, ask for clarification and participate in care and treatment decisions. Feeling disempowered, or unable to participate in care decisions, can distress. |

The operational definition for the theme ‘Information and Participation’ summarises the findings from three underlying subthemes: ‘Importance of personalised care, personalised information’ Underpinning the operational definition of this theme is the importance of personalising symptom management and holistic care. As such, patients needed to feel empowered to initiate non-standardised care and participate in treatment decisions. ‘I had a bit of nausea but as soon as I mentioned it people tried to help me with it’ (M4). Similarly, the right ‘dose’ of information was crucial to patients’ sense of comfort because information could either comfort or frighten and distress. Patients’ information needs were variable and personal. ‘I came to see the anaesthetist and the only question I asked him was you just make sure I wake up … that’s the only thing that really frightened me’ (M2). ‘When delivered well, information underpins comfort (feeling prepared, reassured, accepting; can personalised care)’ Patients gained a sense of comfort from understanding what is currently happening and what is likely to happen. This information helps them prepare for and accept what lies ahead. ‘… the surgeon has been very comforting. He came along and explained, nice warm eyes you know’ (M2). Information about what, when and how to report symptoms or other causes of discomfort supported patient’s ability to personalise care, including safe self-triage, which was common. ‘I never ring the bell straightaway. No, I just hang on [and think] whether why this pain comes in, why the pain, why I got a pain? …I try to play fair and square’ (P4). Information was also important for addressing attitudinal barriers to symptom management. ‘[T]hey did say, however little your pain is it’s good to let them know. Don’t be a tough boy and handle the pain you know which is what I would probably do’ (M8). Information also comforted by reassuring patients their symptoms and side effects they were experiencing was normal and likely to pass. However, sometimes information does not (and indeed cannot) comfort. Under these circumstances, staff experienced in the art and science of informing are pivotal. Balancing information about risk with positivity was important, as was being believable. For one patient, this meant staff being ‘confident but not cocky’ (NZE5). ‘[T]here was one nurse [who] was just very, very good at just calming me down in general and just saying the right things to make me just feel a little bit more comfortable. Others have been very good at explaining the technical side of things…’ (NZE5). ‘Feeling comfortable with staff – the subtle factor influencing personalised care, patient participation’ Feeling comfortable with staff underpinned patients’ willingness and ability to personalise care. For example, patients could be reluctant to ask questions, disclose concerns or use the call bell between times of staff-initiated contact for reasons that included expectations of an unfavourable reaction from staff, not wanting to ‘annoy’ staff, a reluctance to question the ‘experts’ or take up valuable time. ‘I just sort of you know let them do what they’ve got to do. I just want them to do their job yep. And just say nothing to them like I’m alright’ (M6). Staff who demonstrated comforting qualities (refer Engagement and Commitment) helped to minimise these barriers. ‘They’ll show you, there’s the buzzer if you need me, when you need me, just push the buzzer don’t be worried about what time it is’ (M1). However, patients’ preferences for participation varied, and there was a level of comfort to be gained from having confidence in staff to step back from decision making. Patients tended to seek greater involvement when symptoms were poorly controlled, when they were anxious to avoid complications or worried about their safety. At these times, feeling unable to participate in care decisions placed patients in an uncomfortable situation of reluctant (rather than willing) acceptance of care and treatment. This was emotionally distressing and delayed effective symptom management. As such, comfort and participation are inextricably linked. ‘[Discussing pain management] It could be better I think but who am I you know? These guys are professionals. They know what they’re talking about…’ (P5). |

| Perceived and actual competence | The perception of clinical competency promotes a sense of comfort (safety and ease) because patients feel confident in the care provided. However, all staff—clinical and ancillary—have the potential to be comforting by being competent in their role while mindful of patients’ comfort needs. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Perceived and Actual Competence’ summarises the findings from two underlying subthemes: ‘Perception of competence’ Perceiving that staff were competent was comforting in the sense that patients felt at ease and confident in the care provided. ‘… [T]he doctors and the nurses they’re very confident in how they attend you.(How does that make you feel?) Relaxed. And in good care’ (M7). ‘Actual competence – expert comforters’ Staff competence related to each influence is essential. Staff whom patients particularly remembered for their comforting qualities were those that seemed to blend competence and commitment with comforting qualities. In some cases, care was not protocol driven; indeed, some staff had deviated from protocols to make a difference, such as ancillary staff enabling family to visit outside of visiting times, or a nurse letting a sleep-deprived patient sleep in a spare room. Other examples were the surgeon who expertly managed a patients’ pain, the sonographer who described to one patient how well her new heart valve was working and the kaumātua who had knowledge of tikanga Māori (Māori protocols and practices). ‘… [H]e said to me oh you from [place]? I said yeah. And he’s been up there too and that’s where I’m from. That’s my marae. … I identified with him for being from the same place as he is, somebody from home … being Māori and him coming to talk to me it’s good, made a big difference … [It was] uplifting…’ (M5). |

* Patient interviews were coded by ethnicity and interview order, that is, M1 is the first Māori interview, P1 for the first Pacific interview and NZE1 is the first New Zealand European (NZE) interview.

†Examples are from Stage 2 two semi-structured interviews of patients undergoing heart surgery.

NZE, New Zealand European.

Table 4.

Influences on comfort within the clinical environment

| Influence | Operational definition | Subthemes and supporting evidence*† |

| Physical facilities and ambience | Patients feel comfortable (at ease, positive and safe) in a clinical environment in which staff are positive, helpful, have time for all patients’ needs and work as a cohesive team (all roles and all ethnicities) to relieve discomfort and distress. Being away from home, feeling confined and sharing personal space can be difficult therefore supporting patients’ personal preferences for privacy, companionship, quiet and sleep is crucial. Additionally, facilities should be clean, well equipped, physically comfortable (temperature, beds, chairs and fresh air) and support self-comforting strategies such as faith-based activity, distraction (TV and Wi-Fi) and a sense that one’s culture is respected. Family’s unique comforting role is facilitated by staff who acknowledge, welcome and keep family informed; family-friendly space and flexible visiting times are essential. | The operational definition for the theme ‘Physical Facilities and Ambience’ summarises the findings from four underlying subthemes: ‘I’ve never once felt I didn’t want to be here’ Contributing to comfort was an ambience of caring, positivity (staff are friendly and encouraging) and support, irrespective of who was on duty. ‘[What makes you feel cared for]… It’s quite subtle, [but] you soon pick it up… really caring you know. I feel comfortable here type of thing… I’ve never once felt I didn’t want to be here, if I had to be somewhere doing what I’m doing you know this will do me’ (NZE7). ‘Even the people that are bringing breakfast for us and the cleaners, they’re all good, good people’ (M5). Being able to rest/sleep without constant interruptions or disturbance from lights and noise was crucial. Also important was observing staff working as a cohesive team. Perceiving that there were enough staff to meet all patients’ care needs (not just their own) was important. Patients did not like seeing busy, overworked staff, or other patients not getting prompt attention. ‘… I get a bit stressed because I think the nurse in there now she’s amazing …[but] she’s the only one and she’s doing the best job she can … I find it a bit hard because everyone’s demanding things off her … she hasn’t had her break and everybody else you know gets on top of her. I find that really hard to watch’ (NZE6). ‘Facilitating family’s comforting role’ Important here was that family felt welcome, supported and able to be involved through staff actions and behaviour that included making an effort to connect with family, acknowledging and validating family’s situation, supporting advocacy, keeping them informed and through flexible visiting hours. ‘… [M]y husband’s come in every day and that’s been good and hard for him. I’ll be pleased to get home to make it easier for him to be quite honest. He’s a bit naughty he sort of sits there beside me over the hour (when ward is closed to visitors)but then he doesn’t talk. He just sits there and holds my hand’ (NZE4). ‘Physical facilities are clean, well equipped and facilitate all other influences on comfort’ Physical facilities that were important for comfort include those that support privacy, rest and sleep (quiet, comfortable beds), are clean and essential equipment is readily available. ‘… [T]he top-up of the hand gloves, the towel, it’s very good. You know they don’t wait until they run out …(How does that make you feel when you see that?) I feel comfortable, yes. Yeah I feel comfortable you know…I get used to seeing the nurses wear the gloves, so I always feel good. That’s hygienic to me wearing the gloves’ (P6). Also important are family-friendly facilities, family space and an environment that sustains spiritual connectedness (place for prayer/ karakia) and cultural connectedness (such as culturally diverse décor). For example, this is what a tapa cloth wall hanging signified to one Pacific patient: ‘… [O]ur island is respected by here, our culture and everything like that’ (P4). ‘Control over personal space’ The inability to control one’s personal space with respect to lights, noise disturbances, roommates and other patients’ visitors could be very distressing. ‘… [W]hen you want to go to sleep their lights are on and they won’t turn the lights off and that’s happened here all this week, which is 100% worse when you’re feeling awful … I like everything to be right and you can’t have it right when you’re in hospital. This is not your place; you’re a guest here. So my tendency is to not sleep because of that’ (NZE2) Patients appreciated staff-initiated efforts to reduce environmental stressors as they were reluctant to ask roommates, family or staff to curtail activities. |

*Patient interviews were coded by ethnicity and interview order, that is, M1 is the first Māori interview, P1 for the first Pacific interview and NZE1 is the first New Zealand European (NZE) interview.

†Examples are from stage 2 semistructured interviews of patients undergoing heart surgery.

NZE, New Zealand European.

Patients’ personal strategies

The first (inner) layer of the CALM framework relates to patients’ use of personal (often private) strategies to promote comfort and ease distress (see table 1). Three themes were identified within this layer, the first describes patients use of ‘Self-comforting strategies’ during times of distress and uncertainty. Strategies were categorised under four subthemes, which were maintaining positivity; looking for reassuring signs of safety through surveillance of self and others; easing distress using distraction or self-care routines; and developing acceptance of one’s situation by, for example, getting informed, planning and learning to trust (see table 1, self-comforting strategies). The second theme was about comfort arising from feeling ‘Culturally connected’, which related to seeking cultural familiarity, and feeling that one’s cultural norms and values were understood and respected by others (see table 1, culturally connected). The third theme described comfort gained from feeling ‘Spiritually connected’. For some patients, connecting to a higher power through personally significant spiritual or religious practices was comforting (see table 1, spiritually connected). In all three themes, actions and behaviour of family, staff, and factors within the clinical environment moderated the success of these strategies.

Influence of Family

The second layer of the CALM framework related to the theme ‘Family’s unique ability to comfort’ (see table 2, family’s unique ability to comfort). Exploring family comforting in a culturally diverse sample identified that family’s unique connection with patients was pivotal to their ability to comfort. Differences in the way families comforted (whether by shared prayer/karakia, bringing food in and encouraging trust) and who comforted (immediate or extended family) were identified between ethnicities. A shared culture and understanding appeared to underpin the differences in family-initiated comforting observed.

Overall, family were an important buffer to the unfamiliar clinical environment. Additionally, for most patients, having loved ones near and connecting with those who know them best and whom they trust promoted positivity and acceptance of care. Family-initiated comforting activities also included providing holistic care and practical support. However, family could also distress. Patients expressed concern for the safety and well-being of family members and worried about being a burden. Conflict between staff and family could undermine patients’ confidence in treatment decisions. Positive family–staff relationships and family-friendly facilities are the most comforting scenario for patients. These examples demonstrate the integration between family—staff—clinical environment layers that was better understood through stage 2 patient enquiry.

Staff Actions and Behaviour

The third layer of the CALM framework relates to the way staff actions and behaviour influence comfort. Five distinct but integrated themes were identified (see table 3). The first staff-related theme was effective ‘Symptom Management’, which was essential for all symptoms including but not limited to pain. Distressing symptoms varied considerably even in a relatively homogeneous group of patients; therefore, individualised management was important (see table 3, symptom management).

The second staff-related theme, ‘Holistic Care and Assistance’ acknowledges the significant physical and emotional discomfort that can arise from the accumulative effect of symptoms, treatment side effects, unpleasant procedures and loss of functional ability. Holistic care involving multiple, non-pharmacological interventions was essential and complemented pharmacological symptom management. Help with personal care and basic tasks was crucial for a sense of comfort related to feeling cared for and safe (see table 3, holistic care and assistance).

Comfort from holistic care and assistance was enhanced when delivered by staff with qualities described in the third theme, ‘Engagement and Commitment’. This theme relates to a sense of comfort arising from patients’ perceptions that staff were engaged in, and committed to, their welfare. Staff presence was important, which encompassed: the perception of 24 hours nursing presence; contact with doctors via ward rounds; and knowing that staff were available should they be needed. Comforting staff qualities included making an effort to connect, providing reassurance, encouragement and responding to patients’ discomfort or distress using therapeutic strategies tailored to individual need (see table 3, engagement and commitment).

The fourth theme related to staff influence was ‘Information and Participation’, which influenced comfort in complex ways. When delivered well, information influenced comfort by enabling patients to feel prepared, reassured or, at least, accept the need for treatment and care. In addition, information and participation opportunities moderated patients’ ability to personalise many aspects of care important for their comfort. For example, patients were more likely to seek help, disclose concerns or report symptoms when clearly informed about when, why and how to do so. Personalising care in this way also seemed more likely when patients felt comfortable with staff (refer to ‘Engagement and Commitment’). Preferences for participation varied but feeling overlooked, or unable to participate in care decisions could distress (see table 3, information and participation).

The fifth staff-related theme was ‘Perceived and Actual Competence’. Perception of staff competence was comforting in the sense that patients felt at ease and confident in the care provided. Actual competence in all influences was crucial. Interview data indicated that all staff can influence comfort by being competent in their role while mindful that patients’ need for comfort is individual and may occur at any stage of their healthcare experience (see table 3, perceived and actual competence).

Factors within the clinical environment

The outer layer of the CALM framework relates to the theme ‘Physical Facilities and Ambience’, which summarises factors within the clinical environment that influence comfort (see table 4, physical facilities and ambience). Among the factors important here were an ambience of caring and positivity, observing that staff had time for all patients’ needs, having control over one’s personal space (lights and noise) and facilities that were clean, well-equipped and family-friendly.

Discussion

Through a two-stage process commencing with an integrative review involving 62 studies24 followed by semistructured patient interviews, we have: (1) defined patients’ perspectives on comfort and (2) developed a multidimensional framework representing patients’ perspectives on important comfort-related care. Operational definitions for each theme reflect the essence of care that matters to patients and the integrated nature of this care.

Our definition of comfort broadly aligns with others8 10 11 in the sense that comfort is defined as a dynamic and multidimensional state. Similarly, nurse theorists,8 33–37 multiple qualitative studies24 and concept analyses9 10 12 23 38–40 have consistently described the holistic dimensions of comfort and the art of comforting that we believe are captured in our findings. However, the CALM framework differs from most comfort frameworks/models21 41–48 in that patients’ perspectives of all influencing factors are captured in one unifying framework. Differentiating the definition of comfort (the state) from the process of comforting (influencing factors) meant that findings are presented as a more ‘tangible product’ considered essential for implementing qualitative findings into practice49 (p. 765). Operational definitions are generated from rich, in-depth data using methods explicitly exploring patients’ perspectives. We suggest these definitions provide a clearer direction for practice and quality improvement than other published frameworks.21 41–48 50

Implications for practice and quality improvement

Improving patients’ experiences of care is core to healthcare quality. Patient experience is defined as ‘the sum of all interactions, shaped by an organization’s culture, that influence patient perceptions across the continuum of care’51 (p. 10). Improving patient experience, therefore, requires an understanding of what matters to patients during their interactions with healthcare staff. Work in this area has resulted in a range of frameworks and guiding principles.6 52 53 Comfort-related care incorporates many factors considered important for patient experience54 including compassionate care55 56; compassion most simply described as ‘the recognition of and response to the distress and suffering of others’56 (p. 310).

One could assume that initiatives aimed at improving patient experience will also improve comfort. However, all patients interviewed had experienced distressing events even though patient experience indicators at the research site suggested a high-level of person-centred care. Similarly, examples of missed nursing care described in the literature (also known as errors of omission or care rationing)19 22 57–60 relate to care patients described as important for comfort, such as position changes, patient surveillance, comforting/talking with patients, pain management, patient teaching and feeling prepared for discharge. These similarities highlight the inextricable link between care promoting comfort and that inherent in high-quality, safe care.

However, improvement targeting causes of missed nursing care is not the only consideration when aiming to maximise patients’ comfort. First, important care is not specific to the actions of any discipline or indeed clinical staff. Second, staff (any role) may not be able to provide the care they wish to provide because of factors beyond their control (eg, lack of equipment, unsupportive ward culture and absence of evidence-based symptom protocols). Therefore, the breadth and depth of all that matters indicate that maximising patients’ comfort requires an informed and systematic approach aimed at supporting staff to provide the person-centred care they most likely wish to provide. We therefore ask that healthcare leaders consider how the CALM framework may be used to drive a culture of care that maximises patient comfort, beginning with the message that comfort-related care is essential work19 57–61 encompassing a caring, compassionate response to human distress54–56 for which healthcare leaders have accountability to promote, monitor and address omissions.

Three principles underpin application of the CALM framework. The first is appreciating the context-specific nature of comfort, meaning that the detail of care underlying each of the broad influences may differ by condition, ethnicity and age. For example, effective symptom management is crucial for comfort, but distressing symptoms may fluctuate by type and stage of a condition. Similarly, family influenced the comfort of patients of all ethnicities but how patients define family and comforting activities differs by ethnicity, age and stage of condition.31 The second is that individualised care underpins all operational definitions. Efforts to reduce unwarranted variability through standardised care must not be at the expense of the intuitive art of comforting. The third is that all staff can comfort (or distress). Therefore, consider actions of clinical and ancillary staff when applying the framework. Operational definitions can be used to guide conversations with patients, family and staff about their perception of important care for each influence, with identified gaps providing a basis for improvement work.

Transferability

Triggers for the need for comforting care identfed in stage 2 were consistent with those identified in other inpatient settings.24 31 Similarly, the definition of comfort and the CALM framework appear applicable to a range of inpatient populations. Transferability is suggested on the basis that patients of different clinical conditions, age, ethnicity and from a range of inpatient settings within 15 countries24 held similar perspectives on the meaning of comfort and the care that influenced it.

Strengths and limitations

A comprehensive conceptual framework24 focused the exploration of patients’ perspectives in a clinical setting. Definitions are data derived and represent patients’ perspectives. Our method enabled categorisation of concept characteristics in a way that promotes translation into practice; upwards of 60 attributes of comfort and comforting have been previously identified.10 This is the first study that has set out to explore a cultural dimension of comfort. Findings collectively represent perspectives held by Māori, Pacific and NZE participants, suggesting that the CALM framework encompasses culturally responsive care. Importantly, within the CALM framework, the patient determines the extent to which culturally safe care is being provided through their sense of feeling ‘Culturally connected’, that is, they and their family feel welcome; actions and behaviours of others indicate understanding and respect for one’s cultural norms and values. This emphasis is consistent with the notion of unsafe cultural practice as ‘any action which diminishes, demeans or disempowers the cultural identity and well being of an individual’.62

Recruitment stopped when we reached an understanding of how perspectives on comfort broadly differ by ethnicity. However, more can be learnt of the underlying detail for each influencing factor, such as preferences for comforting staff behaviour, attitudes to pain management or body modesty. In accordance with Morse’s view,63 data saturation on all possible context-specific or individual details was not our intent. Peer debriefing by experienced qualitative researchers throughout all stages of the analysis, Māori and Pacific consultation, prolonged engagement (1082 min of interview), negative case analysis and triangulation methods27 promote credibility of the findings. Triangulation—using multiple data sources to produce understanding—was used in both stages of this research. Stage 1 compared findings generated from theoretical and qualitative research (methods triangulation) and involving people from a range of healthcare settings, ages and ethnicities spanning decades of healthcare (triangulation of sources).27 Further triangulation occurred in stage 2 when patient interview data were contrasted with findings from the integrative review and included studies.31 Concept clarification was sought during all interviews.27 However, a limitation is that participants were not asked to comment on the findings.

Implications for research

Replication of this research may lead to further refinements of operational definitions, evaluate claims of transferability and build an evidence base of context-specific care. Exploring staff perspectives on comfort and determinants of comfort-related care in healthcare settings will inform implementation strategies. Research is also required to identify how the art of comforting can be taught and modelled in clinical practice and educational curricula.

The influence of comfort on patients’ outcomes may go beyond patients’ experiences of care (see figure 2). Our interview data indicate that a sense of comfort during one’s healthcare interaction is associated with positive patient–staff relationships, a willingness to disclose concerns, to seek help and to participate in care and treatment, rather than disengage or withdraw. Other qualitative studies exploring comfort have proposed similar outcomes.24 64 An informed, systematic approach to maximising patients’ comfort may, therefore, improve not only patients’ experiences but also population health, particularly in vulnerable sections of the population. These potential benefits warrant further evaluation. Clinically relevant metrics for quantifying comfort and monitoring important aspects of care are also needed.

Figure 2.

Influences, attributes and outcomes of comfort. CALM, Comfort ALways Matters.

Conclusion

This research provides new insights into what comfort means to patients, the care required to promote their comfort and the reasons for which doing so is important. We have developed a definition of comfort and the CALM framework, which can be used by healthcare leaders and clinicians to guide practice and quality initiatives aimed at maximising comfort and minimising distress in a range of inpatient populations. A focus on comfort by individuals is crucial, but leadership will be essential for driving the changes needed to reduce unwarranted variability in care that affects comfort.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all staff in the Cardiac Surgical Unit, Auckland City Hospital, He Kamaka Waiora, Māori Health and Pacific Health, Auckland City Hospital, Auckland New Zealand, for supporting this research. The authors would also like to thank the patients who generously agreed to participate in interviews and share their experiences of care, without whom this research would not have been possible.

Footnotes

Twitter: @brown_acre

Contributors: CW contributed to conceptualisation of the project, research design, undertook data collection, analysis, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and coordinated its multiple revisions. MB contributed to conceptualisation of the project, research design, analysis and interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript. AM contributed to research design, analysis and interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript. AFM contributed to conceptualisation of the project, research design, interpretation of stage 1 data and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award (to CW) and a Deakin University Postgraduate Research Scholarship, Australia (to CW).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was gained from Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (2013–180), the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee (13/CEN/95) and the institution at which recruitment and interviewing occurred (A+5824).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Consistent with our institution’s ethics approval, no additional data generated in this study can be made available.

References

- 1.Picker Institute Europe About Us: Our history & impact. Available: https://www.picker.org/about-us/our-history-impact/ [Accessed Nov 2019].

- 2.Charmel PA, Frampton SB. Building the business case for patient-centered care. Healthc Financ Manage 2008;62:80–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS, To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Patient experience in adult NHS services: improving the experience of care for people using adult NHS services clinical guidance, 2012. Available: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg138/evidence/full-guideline-pdf-185142637 [Accessed Nov 2019]. [PubMed]

- 5.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J. Through the patient's eyes: understanding and promoting patient-centered care, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Picker Institute Europe Principles of patient centred care 2017, 2017. Available: http://www.picker.org/about-us/principles-of-patient-centred-care/ [Accessed May 2017].

- 7.Institute of Medicine, Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolcaba K. Comfort theory and practice. New York: Springer Publishing company, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lowe LM, Cutcliffe JR. A concept analysis of comfort : Cutliffe JR, McKenna HP, The essential concepts of nursing: building blocks for practice. London: Elsevier, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siefert ML. Concept analysis of comfort. Nurs Forum 2002;37:16–23. 10.1111/j.1744-6198.2002.tb01288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morse JM. Comfort: the refocusing of nursing care. Clin Nurs Res 1992;1:91–106. 10.1177/105477389200100110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tutton E, Seers K. An exploration of the concept of comfort. J Clin Nurs 2003;12:689–96. 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00775.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Y-P, Watson R, Tsai Y-F. Dignity in care in the clinical setting: a narrative review. Nurs Ethics 2013;20:168–77. 10.1177/0969733012458609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baillie L. Patient dignity in an acute hospital setting: a case study. Int J Nurs Stud 2009;46:23–37. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray A, Cox J. The roots of compassion and empathy: implementing the Francis report and the search for new models of health care. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc 2015;3:122–30. 10.5750/ejpch.v3i1.962 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Inquiry Independent inquiry into care provided by mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation trust; 2010. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-inquiry-into-care-provided-by-mid-staffordshire-nhs-foundation-trust-january-2001-to-march-2009

- 17.Bauer A. First, do no harm: the patient's experience of avoidable suffering as harm. Patient Exp J 2018;5:13–15. 10.35680/2372-0247.1280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]