Abstract

Objective: Psychiatric symptoms are frequently comorbid with Cushing’s syndrome (CS), a relatively rare condition that results from chronic hypercortisolism. Psychiatric manifestations might be present in the prodromal phase, during the course of the illness, and even after the resolution of CS. Our goals are to review the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in CS; to determine the impact of psychiatric symptoms on morbidity, functioning, and quality of life; and to analyze the impact of treatment of CS on psychiatric symptoms. Methods: A systematic search of the literature database was conducted according to predefined criteria. Two authors independently conducted a focused analysis of the full-text articles and reached a consensus on 17 articles to be included in this review. Results: Overall, studies suggested that psychiatric symptoms—including, most prominently, depression—were present in a significant proportion of patients with CS. They reported lower health-related quality of life, which persisted even following the resolution of hypercortisolism. Though treatment and cure of CS significantly improved psychiatric symptoms, some patients did not achieve complete resolution of psychiatric symptoms and required continued psychiatric treatment. Conclusion: The majority of the literature indicates that psychiatric manifestations are an important part of CS and overall lower health-related quality of life and psychiatric symptoms can persist even after the cure of CS. This emphasizes the significance of early diagnosis for psychiatric management and stresses the importance of monitoring the long-term effects of neurocognitive and psychiatric symptoms and its impact on the quality of life, even after hypercortisolism resolution.

Keywords: Cushing’s syndrome, hypercortisolism, depression, anxiety, quality of life

Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is a relatively rare but serious condition that results from chronic hypercortisolism.1 It causes significant morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular, metabolic, and psychiatric sequelae.2 In addition to the physical features of CS, such as weight gain, central obesity, facial plethora, hirsutism, muscle wasting, and weakness,3 psychiatric manifestations are also a significant part of the condition. A significant proportion of patients with CS experience psychiatric symptoms— largely depression and anxiety disorders— and, although treatment of the underlying hypercortisolism might improve psychiatric symptoms, complete remission of these symptoms might not always be achieved.1

Because psychiatric symptoms might precede, occur during, or remain after the duration of illness,4,5 it is particularly important to recognize that psychiatric manifestations might be the presenting symptom of CS, to monitor psychiatric symptoms throughout disease course, and to continue to follow up on symptom severity and quality of life measures even after resolution of hypercortisolemia. The aims of this study were to review the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms in CS; to determine the impact of psychiatric symptoms on morbidity, functioning, and quality of life; and to analyze the impact of treatment of CS on psychiatric symptoms.

METHODS

We adhered to recommendations in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement,6,7 including designing the analysis before performing the review. However, we did not perform a meta-analysis.

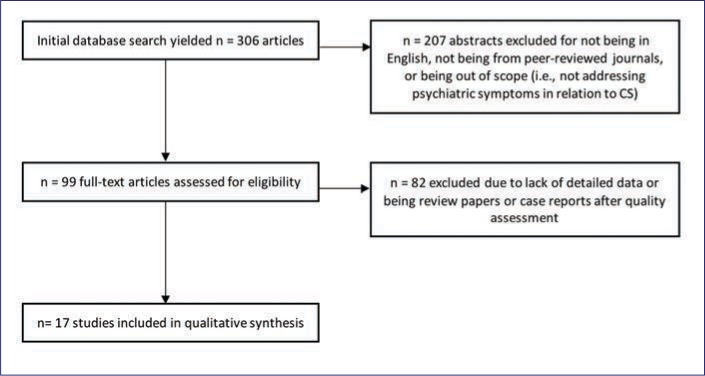

Study selection criteria and methodology. We searched the PubMed database for articles published until the time of search (March 2018). In PubMed, one search term string (“psych*” AND “Cushing*” AND “syndrome”) was used to capture studies of psychiatric symptoms in patients with CS. We included literature with no time limitation to encapsulate all the relevant studies about CS, a relatively rare condition. This initial search yielded 306 relevant articles. Two investigators independently reviewed the abstracts of these studies using the following criteria for inclusion: (1) articles written in English or with an available published English translation; (2) publication in a peer-reviewed journal; (3) studies of patients older than 18 years old; (4) studies that focused on psychiatric symptoms in CS. After eliminating duplicates and abstracts not suitable for inclusion, 99 articles met all these specific criteria. Both reviewers then independently conducted a focused review using the full text of these articles. The reviewers next reached a consensus on which studies to include in this review based on the article’s relevance to the stated goals of this review.

Data extraction. This selection process yielded 17 studies that met the full criteria described above. Two investigators reviewed each full-text article to extract information related to study design, population, and outcomes regarding clinical results. The data on relevant clinical outcomes included psychiatric symptom prevalence, symptom severity, quality of life, and daily functioning. See Figure 1 for an illustration of the search strategy. Research methodology and key findings were derived from the full text and tables of the selected studies.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram of studies for inclusion

RESULTS

The results are depicted in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Results

| REFERENCE | CHARACTERISTICS | MEASURES | FINDINGS | STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly4 | Sample size: 209; age: 39.7 (mean); gender: 47 M, 162 F; psychiatric interview of patient | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Present State Examination | In total, 25 patients experienced psychiatric symptoms, mostly depressive, prior to any signs of CS manifesting. Overall, 120 patients were experiencing or had experienced psychiatric symptoms, mostly depressive, at diagnosis of CS. Diagnoses include anxiety in 26 patients, psychotic illness in 16 patients, mania or hypomania in 6 patients, and confusion in 3 patients. | Strengths: large sample size, four institutions involved; limitation: retrospective study |

| Haskett8 | Sample size: 30; age: 36.7±10.7 (mean±SD); gender: 6 M, 24 F; psychiatric interview of patient and relatives | SADS-L | In total, 25 patients experienced an episode of affective disorder during the course of their CS. Twenty patients experienced depression, 8 patients experienced mania or hypomania, and 2 patients experienced psychotic depression. There was 1 suicide attempt. Schizophrenic illness was not detected. Patients often tried to minimize or hide psychiatric symptoms. | Strength: long term follow-up, multiple sources of information |

| Hudson et al9 | Sample size: 16; age: 44.4±14.1 (mean±SD); gender: 3 M, 16 F; psychiatric interview of patient | Semi-structured diagnostic interview to determine lifetime psychiatric history according to DSM-III criteria | In total, 13 out of 16 patients with CS were diagnosed with major affective disorder in their lifetime according to DSM-III. Relative to patients with major depression, the rate of familial major affective disorder among these patients was found to be significantly lower. | Limitation: sample drawn from a single institution, use of family history method rather than family interview method for ascertaining psychiatric illness in relatives |

| Bolland et al10 | Sample size: 253; age: 39±15 (mean±SD); gender: 81 M, 192 F; retrospective survey | Clinical evaluation | After treatment of CS, the prevalence of mild (not requiring medication) psychiatric symptoms decreased. However, 10 to 20 percent of patients continued to experience psychiatric symptoms at final follow-up. | Strength: comparison group of rheumatoid arthritis patients |

| Sonino et al11 | Sample size: 66; age: 39.2±13.0 (mean±SD); gender: 12 M, 48 F; psychiatric interview of patient | Semi-structured interview based on Paykel’s clinical interview for depression | Overall, 27 percent of patients experienced depression prodromal to CS and 62 percent of patients experienced major depressive disorder during CS. About 70 percent of patients made a full recovery from depression, though there was no significant change in others, and even worsening of depression in two patients. | Limitations: use of semi-structured rather than fully structured psychiatric interviews, use of family history method rather than family interview method for ascertaining psychiatric illness in relatives, small sample size |

| Starkman et al12 | Sample size: 23; age range: 19 to 60; gender: 5 M, 18 F; psychiatric interview of patient | Semi-structured psychiatric interview; Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | Prior to treatment of CS, 18 of 23 patients reported depressed mood. Six patients reported suicidal thoughts and, of these, 2 had attempted suicide after diagnosis of CS. After treatment of CS, 9 of the 18 patients with depressed mood prior reported normal mood; 4 patients reported improvement in depressed mood. Improvement in mood was described as fewer days feeling depressed, shorter duration of depressed episodes, and a less “deep” or “all-encompassing” quality of depression; patients stopped experiencing depression apart from an external trigger. The mean modified Hamilton depression score was 10.8±5.8 at the initial visit but 5.5±4.8 at the last visit, which was a statistically significant difference. | Strengths: large sample size, nationwide survey between 1960 and 2005, included four institutions; limitation: retrospective review |

| Dorn et al13 | Sample size: 33, age: 19 to 30; gender: 3 M, 14 F; psychiatric interviews of patients and questionnaires completed by patients | SADS-L, ADDS, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, POMS, SCL-90-R, STAI, STAS | In total, 67 percent of patients with CS reported psychiatric symptoms during illness. Of those, 50 percent reported major depression. Additionally, 52 percent of all patients enrolled in the study presented with atypical depression, the most common psychiatric manifestation. Of these patients, 47 percent also reported a comorbid psychiatric disorder. | Strength: comparison with Graves’ disease patients; limitation: sample drawn from a single institution |

| Jeffcoate et al14 | Sample size: 40; age: 43 (mean); gender: 12 M, 28 F; psychiatric interview of patient | Standardized psychiatric interview before and after treatment | Among the 40 patients enrolled, depression was the most common psychiatric symptom. In characterizing depression, 5 patients reported severe, 4 reported moderate, and 13 reported mild symptoms. Four patients experienced psychiatric symptoms unrelated to depression. Fourteen patients did not experience any psychiatric symptoms. After metyrapone treatment for hypercortisolism, 6 of the 13 patients who reported mild depression experienced improvement. | Strength: extensive qualitative description of psychiatric symptoms; limitation: small sample size |

| Loosen et al15 | Sample size: 20; age: 39.0±11.2 (mean±SD); gender: 1 M, 19 F; psychiatric interview of patient | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III, RDC, Family History RDC, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, Beck Depression Inventory | Generalized anxiety disorder was present in 79 percent of this cohort, the most common psychiatric diagnosis, while 68 percent of patients experienced major depressive disorder, 53 percent experienced panic disorder, and 63 percent experienced a combination of these 3 diagnoses. Psychiatric symptoms typically manifested at or after the occurrence of physical symptoms of CS, although the onset of panic disorder was associated with chronic stages of CS. These data reveal a syndrome of anxious depression in patients with CS. | Strength: used multiple questionnaires, patient group compared to matched controls; limitation: sample drawn from single institution |

| Langenecker et al16 | Sample size: 21; age: 34.4±14.9 (mean±SD); gender 4 M, 17 F; task administered to patient during fMRI | FEPT, fMRI | Patients with CS had more difficulty distinguishing facial expressions and had less activation in areas of the brain responsible for emotional processing. Hypercortisolism is associated with changes in brain structures related to emotional processing, perception, and regulation. | Strength: patients captured over a 10-year period; limitation: 65 percent formally interviewed |

| Bas-Hoogendam et al17 | Sample size: 21; age: 45.0±7.9 (mean ±SD); gender: 4 M, 17 F; questionnaires completed by patient, MRI scan | MADRS, Inventory of Depression Symptomatology, Beck Anxiety Inventory, Fear Questionnaire, Apathy Scale, Irritability Scale, Cognitive Failures Questionnaire, CS Severity Index, fMRI Faces task | Patients with CS experienced more depressive and anxious symptoms relative to healthy controls. Patients also scored higher on the Apathy Scale and noted higher levels of cognitive failure. Patients had decreased brain activation while processing facial emotions when compared with controls, even in patients who had achieved long-term remission of CS. | Strength: multiple measures used to assess symptom severity; limitation: small sample size |

| Alcalar et al18 | Sample size: 40; age: 39.6±10.6 (mean ±SD); gender: 9 M, 31 F; questionnaires completed by patient | Beck Depression Inventory, SF-36, MBSRQ | Patients reported a lower quality of life related to general health and body image in comparison with healthy controls. There were no differences in depression scores between the two groups. However, the mean Beck Depression Inventory depression score was higher in patients without remission than in patients with remission and healthy controls. On the SF-36, patients without remission scored lower on physical functioning, bodily pain, and general health when compared with patients with remission and healthy controls. Overall, patients with CS scored lower on quality of life measures, had worse body image perception, and had more severe depression compared to healthy controls, especially if surgery was not curative of illness. | Strength: comparison with matched healthy control group; limitation: small sample size |

| Heald et al19 | Sample size: 15; age: 18 to 75; gender: 5 M, 10 F; QOL questionnaires completed by patients, one questionnaire completed by informant | Psychological rating scales: HADS-UK, WHOQOL-BREF, GHQ-28, FACT, SAS1 and SAS2 | Patients with CS scored significantly worse on psychological well-being and psychosocial adjustment questionnaires compared to patients with all other types of pituitary tumors; scores for GHQ, HADS depression, and HADS anxiety were significantly higher. Treated patients with CS continued to perceive themselves as being more depressed, anxious, fatigued, and having poorer physical health and environmental and social adjustment relative to patients with treated other pituitary tumors. | Strength: multiple measures used to assess symptom severity; limitation: small sample size |

| Starkman et al20 | Sample size: 35; age range: 19 to 59; gender: 7 M, 38 F; semi-structured psychiatric interview of patient | Hamilton Depression Scale, Research Diagnostic Criteria | Regarding the severity of psychiatric symptoms, 34 percent of patients with CS in this cohort were considered mild, 26 percent were moderate, 29 percent were severe, and 11 percent were very severe. There was a statistically significant relationship between overall neuropsychiatric disability and levels of cortisol and ACTH. | Strength: multiple measures used to assess symptom severity; limitation: sample drawn from single institution |

| Castinetti et al21 | Sample size: 20; age range: 20 to 63; gender: 7 M, 13 F; retrospective study | Clinical evaluation every 15 to 30 days after initiation of mifepristone treatment | Five out of 20 patients in this cohort experienced psychiatric symptoms. Of these, four patients showed improvement of symptoms within the first week of mifepristone treatment for hypercortisolism. Of four patients who exhibited signs of psychosis, symptoms subsided in three patients after a week of treatment. | Strength: comparison with patients with other types of pituitary tumor; multiple questionnaires administered; limitation: response rate of 62 percent |

| Kelly et al22 | Sample size: 26; age range: 18 to 70; gender: 7 M, 19 F | Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression | Depressive symptoms rated at three and 12 months after treatment were significantly improved relative to before treatment. At three months, 20 of 26 patients experienced improvement in depression. At 12 months, 25 patients experienced improvement. | Strength: studied association between psychiatric symptoms and hormone levels; limitation: relies on subjective reports by patient |

CS: Cushing’s syndrome; SADS-L: Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia, lifetime version; DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; fMNI: functional magnetic resonance imaging; SF-36: Short Form-36; SD: standard deviation; ADDS: Atypical Depression Diagnostic Scale; POMS: Profile of Mood States; SCL-90-R: Symptom Checklist 90-revised; STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory; STAS: State Trait Anger Scale; RDC: Research Diagnostic Criteria; FEPT: Facial Emotion Perception Task; MADRS: Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MBSRQ: Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire; HADS-UK: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – UK version; WHOQOL-BREF: World Health Organization Quality of Life - Brief version; GHQ-28: General Health Questionnaire-28; FACT: Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy; SAS1: Social Adjustment Scale-modified-completed by patient; SAS2: Social Adjustment Scale-modified-completed by another person who knows the patient well.

Psychiatric symptoms. Psychiatric symptoms were present in 20 to 83 percent of patients with CS.4,8–15 These psychiatric manifestations included depression (55–81%),4,8,9,11–15 anxiety (12%),4 mania or hypomania (3–27%),4,8 confusion (1%),4 psychosis (8%),4 and panic disorder (53%).15 These symptoms were present in the prodromal phase, during the course of the illness, and even persisted after resolution of CS.4 Research found that patients with CS made more errors in categorizing facial expressions and had less activation in emotion-processing centers of the brain due to cortisol dysregulation.16 This was true even in patients who had been cured of CS for many years.17

Quality of life. Studies showed that patients with CS had an overall lower health-related quality of life, with lower body image perception and higher levels of depression relative to health controls, particularly if the disease persisted despite surgery.18 In comparison with patients with other forms of pituitary tumors, patients with CS had higher scores for general health, depression, and anxiety questionnaires. They also continued to experience problems in multiple domains of life after cure and perceived themselves as more depressed, anxious, and fatigued as well as exhibiting poorer physical health and environmental and social adjustment.19 Regarding impact on functioning, one study found 34 percent of patients with mild, 26 percent with moderate, 29 percent with severe, and 11 percent with very severe psychiatric disability.20

Impact of treatment. Overall, studies found that, though the treatment and cure of CS significantly improved psychiatric symptoms, 10 to 28 percent of patients did not achieve complete resolution of psychiatric symptoms.10,12 For patients who used mifepristone to control hypercortisolemia during the course of illness and prior to surgical cure, 80 percent of patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms reported improvement within the first week of mifepristone use.21 For depressive symptoms specifically, several studies used the Hamilton rating scale to assess depressed mood, and 72 to 96 percent of affected patients reported statistically significant improvements in their score after the treatment of CS.12,22 Improvements of depressed mood were characterized by a decrease in the frequency of days in which patient felt depressed, each episode lasting for a shorter period of time, and a change in the quality of depressive mood.12 Full recovery occurs in about 75 percent of depressed patients after the cure of CS.11 For patients who used metyrapone to treat hypercortisolemia, depressive symptoms resolved in all markedly/severely depressed, in 75 percent of moderately depressed, and in 50 percent of mildly depressed patients.14

DISCUSSION

The aims of these previous studies were to review the prevalence of psychiatric symptoms of CS; discuss various proper treatments for the patients affected by psychiatric symptoms due to hypercortisolism; emphasize the significance of early diagnosis for psychiatric management and necessary treatment administered in a timely manner for the resolution of hypercortisolism; and stress the importance of monitoring the long-term effects of neurocognitive symptoms, such as concentration and memory problems, in addition to psychiatric symptoms and its impact on the quality of life even after hypercortisolism resolution. In all of the studies reviewed on the psychiatric issues caused by CS, depression seemed to be the most prevalent and significant psychiatric disorder among patients with CS. As many as 90 percent of patients with CS suffer from depression due in part to exposure to excessive and extensive cortisol production from the adrenal glands or prolonged steroid drug use.23 Depression is related to the psychological impact of having an impairing and serious illness as well. Moreover, depression is associated with the effect of CS on self-esteem due to one’s self-degradation of body image because of the adverse physical symptoms of CS, such as weight gain around midsection, the development of a hump between the shoulders, facial plethora, hirsutism, muscle wasting, and weakness. CS leads to additional psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety (second most common), hypomania (third most common), psychosis, and mania.5 Clinicians should consider CS as a differential diagnosis when determining the diagnosis of a new-onset psychiatric illness or prolonged psychiatric symptoms. The reviewed studies show that the most important interventions are control of the cortisol level, lowering the high cortisol state, and the ultimate resolution of hypercortisolism to improve psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders, such as concentration and memory.5,23,24 However, it is important to note that, even after the resolution of hypercortisolism and the improvement of psychiatric and neurocognitive disorders, some patients still experience depression, anxiety, memory, and concentration problems due to residual effects of hypercortisolism on the brain.24 Psychiatric disorders— mainly depression as well as anxiety and mania—could become exacerbated after the resolution of hypercortisolism. The research studies show that psychiatric symptoms caused by CS have a detrimental impact on both physical and mental quality of life of patients with CS. Therefore, close and long-term monitoring of psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms should be standard procedure in the management of CS both in the active phase of the illness and after remission. Although antiglucocorticoids and antidepressants have been suggested as effective choices for the treatment of depressive symptoms, psychotherapy is seen as an important treatment that is proven to be beneficial for depression and anxiety. Inhibitors of corticosteroid production, such as ketoconazole, metyrapone, and aminoglutethimide are generally successful in relieving depressive symptoms, along with other disabling symptoms, and may be used to control symptoms prior to surgical treatment.25,26 However, due to long-standing effects of hypercortisolism on the body and brain, treatment might still be required, even after the resolution of hypercortisolism. In these situations, antidepressants, such as tricyclic agents (e.g., amitriptyline, nortriptyline) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., sertraline, fluoxetine, citalopram), in addition to cognitive behavioral therapies have been found to be particularly effective for depressive symptoms.25 In patients with severe anxiety, benzodiazepines, such as low-dose clonazepam, might be helpful.25

Literature review of studies that agree and disagree with the above findings. Previous authors have also found that psychiatric symptoms might precede CS by months or even years and, across a multitude of studies, the most prevalent psychiatric comorbidity of CS is depression,27–30 though mania and anxiety disorders have also been reported.29,30 Some study cohorts of patients with active CS report a majority of depressive symptoms, without cases of mania or anxiety.28 Additionally, there are several case reports describing CS with an acute psychotic presentation,31,32 though this is much rarer than other psychiatric manifestations. Psychiatric symptoms were found to be caused by anatomical and functional anomalies in the brain areas involved in processing of emotion and cognition, which are only partially restored after the biochemical remission of the disease.33 Broadly, several classes of drugs, including glucocorticoid receptor antagonists, steroidogenesis inhibitors, and pituitary tumor-targeted drugs used for medical treatment of CS, are also effective in treating the accompanying psychiatric symptoms.33 More specifically, in the treatment of depressive symptoms during the active phase of illness, the reduction of glucocorticoid synthesis or action with metyrapone, ketoconazole, or mifepristone, rather than treatment with antidepressant medications, is generally found to be successful.30,34 Many studies have found that, though the resolution of hypercortisolism improves the overall prevalence of the psychiatric and neurocognitive symptoms, patients might still experience impaired cognitive function and memory due to persisting brain volume loss.27,29,30,35–38 Prior studies reported a strong association between elevated cortisol levels and depression, hippocampal atrophy, and cognitive impairment,39 supporting the findings in our review. It seems to be the consensus that patients do not completely return to their premorbid level of functioning and quality of life and cognitive function continue to be impaired despite long-term cure.29,30,33,40 Furthermore, long-standing hypercortisolism might confer a degree of irreversibility to the pathological processes,29 and studies have shown that chronically elevated levels of glucocorticoids have detrimental effects on cognition,37,40–42 though there is also evidence suggesting that changes to the hippocampal region caused by hypercortisolism are at least partly reversible.43,44

Limitations. Few research studies have focused on the neurocognitive symptoms, such as concentration and memory impairments, affected due to the impact of a high-cortisol state on the hippocampus. Other common symptoms of CS, such as insomnia and fatigue, are also understudied. Head-to-head comparisons of treatment interventions of depressive symptoms in CS are also lacking, leading to difficulties faced by clinicians in guiding treatment for patients who do not readily respond to conventional interventions.

CONCLUSION

Early diagnosis of hypercortisolism aids in the process of normalizing excessive cortisol levels, thus preventing or lessening the severity of psychiatric symptoms in CS patients, especially if psychiatric symptoms are commonly the presenting features of CS. Going forward, a timely diagnosis and treatment initiation using antiglucocorticoids, antidepressants, and psychotherapy, monitoring the psychiatric symptoms of patients with CS during illness and postresolution of hypercortisolism are imperative to achieve the best results in resolving the psychiatric characteristics of CS and improving their quality of life.

REFERENCES

- Santos A, Resmini E, Pascual JC et al. Psychiatric symptoms in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: prevalence, diagnosis and management. Drugs. 2017;77(8):829–842. doi: 10.1007/s40265-017-0735-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson AB et al. Diagnosis and complications of Cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593–5602. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome: update on signs, symptoms and biochemical screening. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(4):M33–M38. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WF. Psychiatric aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. QJM. 1996;89(7):543–551. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/89.7.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang A, O’Sullivan AJ, Diamond T et al. Psychiatric symptoms as a clinical presentation of Cushing’s syndrome. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-12-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskett RF. Diagnostic categorization of psychiatric disturbance in Cushing’s syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(8):911–916. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.8.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hudson MS, Griffing GT et al. Phenomenology and family history of affective disorder in Cushing’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144(7):951–953. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.7.951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolland MJ, Holdaway IM, Berkeley JE et al. Mortality and morbidity in Cushing’s syndrome in New Zealand. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75(4):436–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonino N, Fava GA, Belluardo P et al. Course of depression in Cushing’s syndrome: response to treatment and comparison with Graves’ disease. Horm Res. 1993;39(5–6):202–206. doi: 10.1159/000182736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkman MN, Schteingart DE, Schork MA. Cushing’s syndrome after treatment: changes in cortisol and ACTH levels, and amelioration of the depressive syndrome. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Burgess ES, Dubbert B et al. Psychopathology in patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome: ‘atypical’ or melancholic features. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1995;43(4):433–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1995.tb02614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoate WJ, Silverstone JT, Edwards CRW, Besser GM. Psychiatric manifestations of cushing’s syndrome: response to lowering of plasma cortisol. QJM. 1979;48(191):465–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loosen P, Chambliss B, DeBold C et al. Psychiatric phenomenology in Cushing’s disease. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1992;25(4):192–198. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langenecker SA, Weisenbach SL, Giordani B et al. Impact of chronic hypercortisolemia on affective processing. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62(1):217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bas-Hoogendam JM, Andela CD, van der Werff SJ et al. Altered neural processing of emotional faces in remitted Cushing’s disease. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;59:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcalar N, Ozkan S, Kadioglu P et al. Evaluation of depression, quality of life and body image in patients with Cushing’s disease. Pituitary. 2013;16(3):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s11102-012-0425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heald AH, Ghosh S, Bray S et al. Long-term negative impact on quality of life in patients with successfully treated Cushing’s disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;61(4):458–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkman MN, Schteingart DE. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of patients with Cushing’s syndrome. Relationship to cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141(2):215–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castinetti F, Fassnacht M, Johanssen S et al. Merits and pitfalls of mifepristone in Cushing’s syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160(6):1003–1010. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WF, Checkley SA, Bender DA, Mashiter K. Cushing’s syndrome and depression—a prospective study of 26 patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;142:16–19. doi: 10.1192/bjp.142.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleman D. Psychiatric issues of Cushing’s patients. https://csrf.net/coping-with-cushings/psychiatric-issues-of-cushings-patients/ Accessed March 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pivonello R, Simeoli C, De Martino MC et al. Neuropsychiatric disorders in Cushing’s syndrome. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:129. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonino N, Fava GA. Psychiatric disorders associated with Cushing’s syndrome. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2001;15(5):361–73. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200115050-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obinata D, Yamaguchi K, Hirano D et al. Preoperative management of Cushing’s syndrome with metyrapone for severe psychiatric disturbances. Int J Urol. 2008;15(4):361–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratek A, Kozmin-Burzynska A, Gorniak E, Krysta K. Psychiatric disorders associated with Cushing’s syndrome. Psychiatr Danub. 2015;27:S339–S343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly WF, Kelly MJ, Faragher BA. A prospective study of psychiatric and psychological aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1996;45(6):715–720. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.8690878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonino N, Fallo F, Fava GA. Psychosomatic aspects of Cushing’s syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11(2):95–104. doi: 10.1007/s11154-009-9123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AM, Tiemensma J, Romijn JA. Neuropsychiatric disorders in Cushing’s syndrome. Neuroendocrinology. 2010;92(1):65–70. doi: 10.1159/000314317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch D, Orr G, Kantarovich V et al. Cushing’s syndrome presenting as a schizophrenia-like psychotic state. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2000;37(1):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Chen J, Ma Y, Chen Z. Case report of Cushing’s syndrome with an acute psychotic presentation. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016;28(3):169–172. doi: 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernini G, Tricò D. Cushing’s Syndrome and steroid dementia. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2016;10(1):50–55. doi: 10.2174/1872214810666160809113021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolkowitz OM, Reus VI, Manfredi F et al. Antiglucocorticoid strategies in hypercortisolemic states. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1992;28(3):247–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt T, Ludecke D, Spies L et al. Hippocampal and cerebellar atrophy in patients with Cushing’s disease. Neurosurg Focus. 2015;39(5):E5. doi: 10.3171/2015.8.FOCUS15324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivonello R, De Martino MC, De Leo M et al. Cushing’s syndrome: aftermath of the cure. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51(8):1381–1391. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000800025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkman MN, Gebarski SS, Berent S, Schteingart DE. Hippocampal formation volume, memory dysfunction, and cortisol levels in patients with Cushing’s syndrome. Biol Psychiatry. 1992;32(9):756–765. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(92)90079-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YF, Li YF, Chen X, Sun QF. Neuropsychiatric disorders and cognitive dysfunction in patients with Cushing’s disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126(16):3156–3160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, Varghese F, McEwen B. Association of depression with medical illness: does cortisol play a role? Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00473-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resmini E, Santos A, Webb SM. Cortisol excess and the brain. Front Horm Res. 2016;46:74–86. doi: 10.1159/000443868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkman MN, Giordani B, Berent S et al. Elevated cortisol levels in Cushing’s disease are associated with cognitive decrements. Psychosom Med. 2001;63(6):985–993. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200111000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiemensma J, Kokshoorn NE, Biermasz NR et al. Subtle cognitive impairments in patients with long-term cure of Cushing’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2699–2714. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starkman MN, Giordani B, Gebarski SS et al. Decrease in cortisol reverses human hippocampal atrophy following treatment of Cushing’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46(12):1595–1602. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JN, Giordani B, Schteingart DE et al. Patterns of cognitive change over time and relationship to age following successful treatment of Cushing’s disease. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2007;13(1):21–29. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]