Abstract

A 67-year-old man with a prior heart failure presented with fever, cough and dyspnea for 4 days. Physical examination showed bilateral rales on the lung exam, yet no lower extremity edema. The combination of symptoms, elevated inflammatory markers, normal baseline pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 and positive swab suggested coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) rather than heart failure exacerbation. We discuss the challenges in management of ARDS in COVID-19 patients that may initially mimic as acute exacerbation of heart failure.

Keywords: COVID-19, Novel human coronavirus, ARDS, Heart failure

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. The rapidly evolving pandemic of COVID-19 affected a total of 395,011 patients with 12,754 deaths in the US as of early April 2020 [1]. COVID-19 can present as respiratory tract infection that can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [2]. The poor outcomes are reported in patients with underlying heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, malignancy and chronic kidney disease [3]. A high mortality rate of 11% is reported in patients with underlying heart failure [4]. Therefore, it is critical to stratify these high-risk patients and provide prompt management based on the severity. Here, we report clinical features, radiologic findings, and management of a case with COVID-19 ARDS that can mimic heart failure exacerbation.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man with a past medical history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, ischemic cardiomyopathy with left ventricular aneurysm and an ejection fraction of 15% presented to the emergency department (ED) with fever, cough and dyspnea for 4 days.

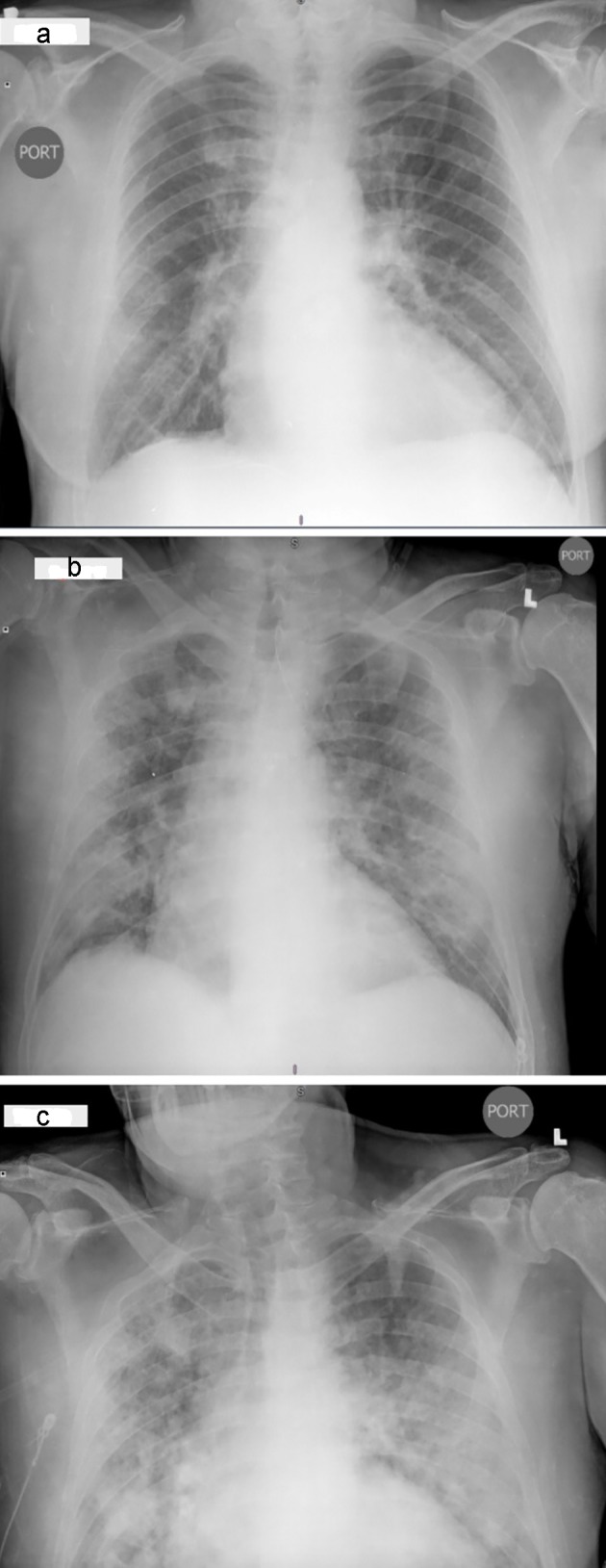

On presentation, he was febrile to 100.6 °F, hypertensive to 157/70 mm Hg and hypoxic with an oxygen saturation (SaO2) of 88% on ambient room air. His electrocardiogram (EKG) was unremarkable for any acute change. The chest X-ray revealed bilateral diffuse ground-glass opacities (GGOs) in lungs (Fig. 1). The pertinent laboratory findings are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Radiographic findings in a COVID-19 patient. Baseline chest X-ray (CXR) in posteroanterior (PA) view showing ground-glass opacities (GGOs) in bilateral lung bases and mid regions (a). CXR in PA view showing interval worsening of infiltrates (b). CXR in PA view showing severe worsening of GGOs involving apical, mid and lower lung fields (c).

Table 1. Laboratory Findings in a COVID-19 Patient.

| Analytes | Admission | Day 5 | Day 10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (cells/µL) | 5.58 | 4.6 | 10.4 |

| Lymphocyte (%) | 28 | 16 | 4 |

| AST (U/L) | 34 | 502 | 257 |

| ALT (U/L) | 34 | 233 | 187 |

| ALP (U/L) | 85 | 183 | 262 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.4 | 1.2 | 2.2 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 58 | - | - |

| pH | 7.45 | 7.54 | 7.52 |

| PCO2 (mm Hg) | 38 | 29 | 33 |

| HCO3 (mEq/L) | 36 | 24 | 27 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.2 | 1.8 | 2.2 |

| D-dimer (µg/L) | 154 | 245 | 7504 |

| High-sensitivity CRP (mg/L) | 155 | 262 | > 300 |

| LDH (U/L) | 263 | 1024 | 665 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 0.28 | 0.43 | 1.02 |

| Troponin (ng/mL) | Negative | - | - |

| Pro-BNP (pg/mL) | 300 | ||

| Blood culture (CFU/mL) | NGTD | NGTD | NGTD |

| Novel COVID-19 nasopharyngeal PCR (+/-) | Positive | - | - |

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019; WBC: white blood cell; CFU: colony-forming units; AST: aspartate transaminase; ALT: alanine transaminase; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; LDL: low-density lipoprotein; PCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide; HCO3: bicarbonate; CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; PCT: procalcitonin; BNP: B-type natriuretic peptide.

The clinical symptoms, elevated inflammatory markers, PaO2/FiO2 < 300 and eventual positive nasal swab were consistent with COVID-19 pneumonia and mild ARDS. Patient was started on non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, with off-label tocilizumab 400 mg × 1, hydroxychloroquine 400 mg BID × day 1, then 400 mg for the next 4 days, and 400 mg azithromycin for 5 days. The patient was started on optimal home dose diuretic. The optimal heart regimen including valsartan-sacubitril 49 - 51 mg BID was held due to inconsistent reports of worsening of COVID-19 secondary to renin angiotensin aldosterone system medication. Initially statins were continued, but on day 4 were stopped given the worsening of primary transaminitis due to COVID-19 in the setting of statins. Despite management our patient died in the setting of COVID-19 ARDS causing respiratory failure.

Discussion

The COVID-19 with ARDS can mimic exacerbation of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) on imaging. The Berlin criteria can be used in differentiating ARDS and cardiac failure by assessing the timing of symptoms, bilateral opacities, volume overload, value of brain natriuretic peptide and echocardiography findings [5]. Based on euvolemia, baseline cardiac markers and ejection fraction, our patient had ARDS due to COVID-19 rather than acute HFrEF.

SARS CoV-2 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 (ACE-2) receptor using spike protein, and pH, or lipid mediated endocytosis. The acidic endosomal pH activates virion, causing its release into the cytoplasm. The free virion undergoes transcription and translation to form new virions that ultimately exported out of cells in a new vesicle [6]. ACE-2 receptors are predominantly found in vascular endothelial cells and type 2 pneumocytes. SARS CoV-2 downregulates ACE-2 receptors in the cardiopulmonary system, leading to accumulation of angiotensin-II. Furthermore, increased expression of ACE-2 due to chronic RAAS activation increases COVID-19 predisposition in the setting of prior heart failure [7]. Literature review showed that angiotensin-II plays a critical role in widespread tissue injury by igniting cytokine storm consisting of more than 150 inflammatory mediators. Major inflammatory responses cause intracellular apoptosis by reactive oxygen species (ROS), proteasomal degradation, lipolysis and caspase mediated cytotoxicity driven by increased NkB levels that ultimately increases tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) [8]. The intracellular apoptosis is also enhanced by dephosphorylation of Akt, decreased atrogin 1 and phosphorylation of FOXO-1, a transcription factor that causes apoptosis of cardiac and pulmonary endothelial tissues, a probable explanation of cytotoxicity seen in the pulmonary system causing ARDS due to COVID-19 in our patient.

The use of ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in congestive cardiac failure with COVID-19 has conflicting results. ACE-2 inhibits angiotensin-II. RAAS inhibitors blockers can upregulate the ACE-2 receptors enhancing viral invasion [9]. Based on these recommendations, we stopped the initial regimen of valsartan-sacubitril in our patient. Some studies reported that RAAS inhibitors can limit cytotoxicity by inhibiting the angiotensin-II through indirect upregulation of ACE-2 [10]. Taking both RAAS blockers and statins into consideration, both drugs work by reducing endothelial dysfunction through decreasing ACE-2/Ang (1-7)/MAS axis and FOXO phosphorylation mediated apoptosis [11]. We reconciled the home dose statin in our patient that potentially worsened the transaminitis of COVID-19 as an adverse effect.

Given the patient’s elevated inflammatory markers, chest radiographic findings of bilateral diffuse ground-glass (GG) infiltrates and positive nasopharyngeal swab for COVID-19, the patient was treated for COVID-19 with non-invasive ventilation for ARDS. Gautret et al reported that azithromycin in combination with hydroxychloroquine has shown significant viral eradication (P < 0.001) [12]. In our case, we administered a combined regimen of off-label tocilizumab single dose, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for 5 days. Despite the management directed toward COVID-19 infection, and maintaining cardiopulmonary function, our patient died of cardiopulmonary failure.

Learning points

COVID-19 ARDS can mimic heart failure on imaging, therefore volume status and laboratory markers should be evaluated for clinical exacerbation of heart failure.

ACE inhibitors/ARBs reconciliation in COVID-19 is ongoing debate, and likely can be safely restarted in COVID-19 patients, but the effect can be controversial either helpful, detrimental, or both. Large population studies are needed to fully evaluate the outcomes of ACE inhibitors in COVID-19.

Statins have an anti-inflammatory effect in COVID-19, and can be restarted with an added benefit, but liver function test can likely be done as a follow-up to see any worsening of transaminitis. Further larger trials are needed to confirm this effect.

COVID-19 can have high mortality in patients with underlying heart failure.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was received. None of the authors have disclosures relevant to this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Informed Consent

We have provided the informed consent with this manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed in the preparation and editing of manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

- 1. CDC: Cases in US: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html.

- 2.Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) Indian J Pediatr. 2020;87(4):281–286. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guan WJ, Liang WH, Zhao Y, Liang HR, Chen ZS, Li YM, Liu XQ. et al. Comorbidity and its impact on 1590 patients with Covid-19 in China: A Nationwide Analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00547-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Team TNCPERE. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) China CDC Weekly. 2020;2(8):1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferguson ND, Fan E, Camporota L, Antonelli M, Anzueto A, Beale R, Brochard L. et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rationale, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(10):1573–1582. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2682-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Yang P, Liu K, Guo F, Zhang Y, Zhang G, Jiang C. SARS coronavirus entry into host cells through a novel clathrin- and caveolae-independent endocytic pathway. Cell Res. 2008;18(2):290–301. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, Bi Z. et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109(5):531–538. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang R, Alam G, Zagariya A, Gidea C, Pinillos H, Lalude O, Choudhary G. et al. Apoptosis of lung epithelial cells in response to TNF-alpha requires angiotensin II generation de novo. J Cell Physiol. 2000;185(2):253–259. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200011)185:2<253::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, Chuich T, Laracy J, Bondi-Zoccai G, Brown TS. et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrario CM, Jessup J, Chappell MC, Averill DB, Brosnihan KB, Tallant EA, Diz DI. et al. Effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockers on cardiac angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. Circulation. 2005;111(20):2605–2610. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.510461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedson DS. Treating the host response to emerging virus diseases: lessons learned from sepsis, pneumonia, influenza and Ebola. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(21):421. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.11.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, Doudier B. et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020:105949. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.