Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Aortic insufficiency (AI) is common in patients with proximal aortic disease, but limited options exist to facilitate aortic valve repair (AVr) in this population. This study reports ‘real-world’ early results of AVr using newly FDA-approved trileaflet and bicuspid geometric annuloplasty rings for patients with AI undergoing proximal aortic repair (PAR) in a single referral centre.

METHODS

All patients undergoing AVr with a rigid internal geometric annuloplasty ring (n = 47) in conjunction with PAR (ascending +/− root +/− arch) were included. Thirty-six patients underwent AVr with a trileaflet ring, and 11 patients underwent AVr with a bicuspid ring. The rings were implanted in the subannular position, and concomitant leaflet repair was performed if required for cusp prolapse identified after ring placement.

RESULTS

The median age was 58 years [interquartile range (IQR) 46–70]. PAR included supracoronary ascending replacement in 26 (55%) patients and remodelling valve-sparing root replacement with selective sinus replacement in 20 (42%) patients. Arch replacement was performed in 38 (81%) patients, including hemi-arch in 34 patients and total arch in 4 patients. There was no 30-day/in-hospital mortality. Preoperative AI was 3–4+ in 37 (79%) patients. Forty-one (87%) patients had zero–trace AI on post-repair transoesophageal echocardiography, and 6 patients had 1+ AI. The median early post-repair mean gradient was 13 mmHg (IQR 5–20). Follow-up imaging was available in 32 (68%) patients at a median of 11 months (IQR 10–13) postsurgery. AI was ≤1+ in 97% of patients with 2+ AI in 1 patient. All patients were alive and free from aortic valve reintervention at last follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Early results with geometric rigid internal ring annuloplasty for AVr in patients undergoing PAR appear promising and allow a standardized approach to repair with annular diameter reduction and cusp plication when needed. Longer-term follow-up will be required to ensure the durability of the procedure.

Keywords: Aortic valve repair, Annuloplasty ring

INTRODUCTION

Surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) has long been the mainstay treatment of patients with severe aortic insufficiency (AI), improving both prognosis and quality of life. Prosthetic AVR, however, exposes patients to prosthesis-related complication rates as high as ∼50% at 10 years following AVR for AI [1]. Furthermore, mitral valve repair has been associated with improved survival compared to replacement, prompting focus on techniques to repair the aortic valve (AVr) over the past 15 years [2]. AVr has traditionally included subcommissural suture annuloplasty for annular diameter reduction, but suture annuloplasty provides only modest annular reduction and has been associated with late annular redilation and recurrent AI [3, 4]. Suture annuloplasty is further limited by an inability to recapitulate the elliptical geometry of the annulus, which could result in poor coaptation of leaflets and recurrent AI [4].

More recently, a rigid internal geometric annuloplasty ring has been developed that reduces annular diameter and restores elliptical geometry, thereby allowing a standardized annuloplasty and theoretically mitigating recurrent annular dilation as a mechanism for late AI [5]. The initial device designed for trileaflet valves (HAART 300; BioStable Science & Engineering, Inc., Austin, TX, USA) received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in the USA in March 2017, whereas the bicuspid device (HAART 200), which remodels the bicuspid annulus to a 50/50% circular geometry [6], was approved in August 2017. Early results from Europe of patients undergoing AVr including HAART geometric annuloplasty have demonstrated safety and efficacy, with few annuloplasty-related complications and high freedom from reintervention [6–10]. However, no data exist to date on postapproval use in the USA. In addition, aortic root disease is a more common cause of AI than primary valve disease in the modern era [11] and limited data exist on use of the device in patients with concomitant proximal aortic pathology [12]. Given this knowledge gap in the literature, the current study describes early experience using these newly FDA-approved geometric annuloplasty rings for trileaflet (TAV) and bicuspid (BAV) AVr in patients undergoing concomitant proximal aortic surgery in a single referral aortic centre in the USA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population and data collection

A prospectively maintained institutional aortic surgery database from a single referral aortic centre (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA) was queried for all patients undergoing AVr with a rigid internal geometric annuloplasty ring (HAART 200 and 300) in conjunction with proximal aortic repair (PAR) following initial FDA approval in March 2017 through August 2019. PAR was defined as any procedure involving the supracoronary ascending aorta, with or without aortic root and/or aortic arch, performed via median sternotomy and using cardiopulmonary bypass with or without hypothermic circulatory arrest [13]. The primary indication for concomitant AVr was AI (≥2+) or annular stabilization in patients with lesser degrees of AI undergoing remodelling valve-sparing root replacement (VSRR). Demographics, procedural characteristics and postoperative events were stratified by BAV or TAV morphology. Comorbidities and patient characteristics were defined using Society of Thoracic Surgeons definitions [14]. All patients undergo lifelong follow-up at the Duke University Center for Aortic Disease including clinical assessment and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging or transthoracic echocardiographic analysis of cardiac and valve function performed 6–12 months postdischarge and then annually thereafter [15]. Data were collected through the last follow-up visit by the study termination date of August 2019. The study was approved by Duke University Institutional Review Board, and need for individual patient consent was waived.

Operative technique

All PAR operations were performed with intraoperative transoesophageal echocardiography monitoring as previously described [16–20]. Preoperative grading of AI was in accordance with ACC/AHA guidelines [21].

After cardioplegic arrest and mobilization of the proximal aorta, the valve leaflets were carefully inspected. Leaflets with more than mild calcification were excluded from repair, as were patients with type III AI due to cusp restriction given the known poor long-term outcomes for AVr in this scenario [22]. For BAV with excess fibrous raphe tissue, shaving of the raphe using an 11-blade scalpel while preserving the underlying cusp tissue was performed in select cases. The presence of stress fenestrations was not a contraindication to AVr, although valves with multiple large fenestrations were not chosen for preservation [22]. As the cases presented in this series lie within our institutional learning curve with this new device (the learning curve for AVr is generally recognized to be ∼40–60 cases [23]), we attempted to be conservative in our practice of valve preservation.

Once the decision was made to spare the valve, the native aortic annulus was measured using a Hegar dilator to obtain the prerepair diameter. For TAV, the cusp intercommissural free margin lengths were then measured using specially designed ball sizers specific to the HAART 300 device as previously described [9], and the ring size chosen based upon the smaller (if all intercommissural lengths not equal) length. For BAV, the sizer specific to the HAART 200 device was used to measure the intercommissural free margin length of the non-fused/reference cusp (most commonly the non-coronary cusp in Sievers type I valves) as previously described [6]. With regard to BAV repair with the HAART 200 ring, all patients in this series were type A (symmetrical) or type B (asymmetrical) BAV according to the newly proposed classification scheme from the Brussels and Homburg groups [24]. Although there were no patients with type C (very asymmetrical) BAV in this series, these patients are better treated with a HAART 300 ring to ‘tricuspidize’ the valve. Once ring size was chosen using this validated sizing strategy, the ring was implanted using previously described techniques [5–10, 12] (Fig. 1).

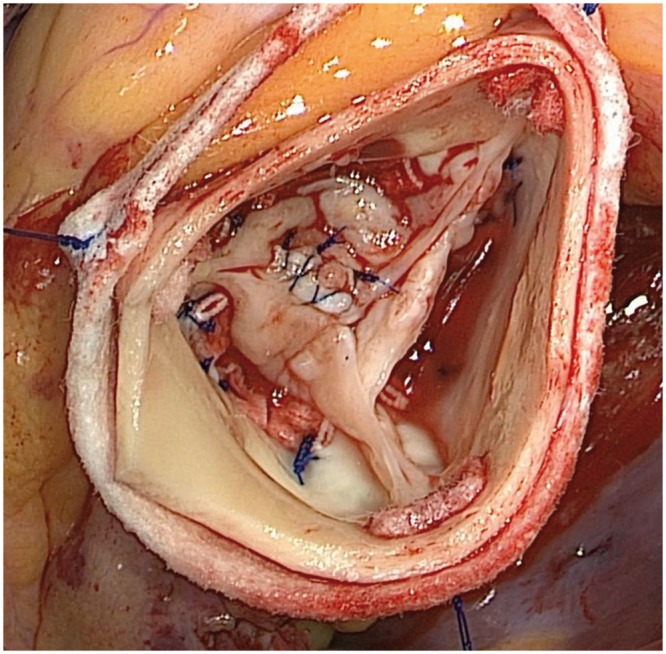

Figure 1:

Intraoperative photograph of postrepair trileaflet aortic valve using HAART 300 internal geometric annuloplasty ring. This patient did not require adjunctive cusp plication to restore valve competence.

After ring placement for TAV, any cusp prolapse was corrected using plication sutures 7-0 polypropylene to equalize free-edge length and raise the effective cusp height to >8 mm as previously described [25]. For BAV, Schäfers’ leaflet reconstruction techniques were utilized [26]. Specifically, if the non-fused/reference cusp was elongated, the free margin was shortened with 7-0 polypropylene sutures to elevate the free margin to an effective height of >8 mm as described for TAV. Finally, the incomplete cleft/raphe of the conjoint cusp was closed with interrupted 5-0 polypropylene sutures to equalize the cusp length with the non-fused/reference cusp (Fig. 2).

Figure 2:

Intraoperative photograph of postrepair Sievers type I R/l congenital bicuspid aortic valve using HAART 200 internal geometric annuloplasty ring and cleft closure of conjoint cusp. This patient did not require free margin shortening/plication of the reference non-coronary cusp.

The root or supracoronary graft portion of the operation was performed after the annuloplasty ring had been sewn into place. For patients undergoing VSRR, the aortic root remodelling technique was used with the HAART ring providing annular stabilization. The pathological sinuses were excised leaving a 4-mm rim of native aortic wall attached to the annulus (Fig. 3); coronary buttons were fashioned when the left and/or right sinuses were replaced. A Valsalva graft (Terumo Aortic, Sunrise, FL, USA) 5 mm larger than the size of the implanted ring was utilized with individual scallops fashioned in the sinus portion of the graft. The graft was then sewn to the aortic annulus, incorporating the supra-annular pledgets of the anchoring sutures for the valve ring, using running 4-0 polypropylene sutures (Fig. 4). A modification of Urbanski’s technique of selective sinus replacement was utilized in patients without a connective tissue disorder and pathological dilation of only 1 or 2 sinuses [27]. In BAV patients, this frequently is the non-coronary sinus as has been previously noted by others [28], although patients with atherosclerotic disease may also have pathological involvement of only 1 or 2 sinuses.

Figure 3:

Intraoperative photograph of patient with Loeys–Dietz syndrome undergoing remodelling valve-sparing root replacement with replacement of all 3 sinuses given the diagnosis of a connective tissue disorder. The HAART 300 ring has been placed, and the pathological sinus tissue excised with coronary buttons fashioned.

Figure 4:

Intraoperative photographs of a patient with Marfan syndrome undergoing remodelling valve-sparing root replacement with replacement of all 3 sinuses given the diagnosis of a connective tissue disorder. (A) The sinus portion of the Valsalva graft has been fashioned to create 3 scallops, which are being sewn to the aortic annulus incorporating the supra-annular pledgets of the valve ring. (B) The completed right sinus portion of the graft prior to reimplantation of the right coronary button.

Outcomes and statistics

The primary outcome was degree of AI and transvalvular gradient on late follow-up imaging. Secondary outcomes included 30-day/in-hospital complications, need for reoperation for recurrent AI and New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies. Continuous variables are presented as median with interquartile range (IQR). All analyses were performed using R version 3.5.1 (Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Forty-seven patients met study inclusion criteria including 77% (n = 36/47) with TAV and 23% (n = 11/47) with BAV. All patients underwent PAR plus AVr between September 2017 and August 2019. Baseline patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median age of the study population was 58 years (IQR 46–70) with bicuspid patients being nearly 2 decades younger on average. Four patients had a connective tissue disorder confirmed by genetic testing [Marfan syndrome (n = 2), Loeys–Dietz type I (n = 1) and undefined (n = 1)]. The majority of patients were NYHA class I (55%, n = 26) or II (43%, n = 20) at baseline. Preoperative AI was ≥2+ in 37 (79%) patients; of the remaining 10 patients with <2+ baseline AI, internal ring annuloplasty was performed for annular stabilization as part of VSRR.

Table 1:

Baseline patient characteristics stratified by native aortic valve morphology

| Variables | Total (n = 47) | Trileaflet aortic valve (n = 36) | Bicuspid aortic valve (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 58 (46–70) | 61 (47–70) | 43 (40–61) |

| Male gender, % (n) | 79 (37) | 81 (29) | 73 (8) |

| BMI (kg/m2), median (IQR) | 28 (26–31) | 29 (26–31) | 27 (25–30) |

| Caucasian, % (n) | 77 (36) | 74 (26) | 91 (10) |

| Connective tissue disorder,a % (n) | 9 (4) | 11 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 62 (29) | 67 (24) | 46 (5) |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % (n) | 34 (16) | 42 (15) | 9 (1) |

| Coronary artery disease, % (n) | 19 (9) | 25 (9) | 0 (0) |

| Diabetes, % (n) | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Prior stroke/TIA, % (n) | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic kidney disease (serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dl), % (n) | 9 (4) | 11 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Prior or current smoker, % (n) | 40 (19) | 53 (19) | 0 (0) |

| Prior aortic surgery, % (n) | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| ASA class, % (n) | |||

| 2 | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| 3 | 66 (31) | 56 (20) | 100 (11) |

| 4 | 32 (15) | 42 (15) | 0 (0) |

| Non-elective operation, % (n) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Baseline NYHA class, % (n) | |||

| I | 55 (26) | 53 (19) | 64 (7) |

| II | 43 (20) | 44 (16) | 36 (4) |

| III | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| IV | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Baseline EF (%), % (n) | |||

| <55 | 15 (7) | 19 (7) | 0 (0) |

| ≥55 | 85 (40) | 81 (29) | 100 (11) |

| Preoperative AI grade, % (n) | |||

| Noneb | 4 (2) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) |

| 1+b | 17 (8) | 19 (7) | 9 (1) |

| 2+ | 36 (17) | 36 (13) | 36 (4) |

| 3+ | 21 (10) | 19 (7) | 27 (3) |

| 4+ | 21 (10) | 19 (7) | 27 (3) |

| Median preoperative annular diameter (mm) (IQR) | 27 (25–29) | 27 (25–28) | 27 (25–29) |

| Median maximum aortic diameter (cm) (IQR) | 5.3 (5.1–5.9) | 5.3 (5.2–5.9) | 5.1 (4.9–5.3) |

| Sievers classification, % (n) | |||

| Type 1 R/L | 100 (11) | ||

Connective tissue disorder confirmed by genetic testing [Marfan syndrome (n = 2), Loeys–Dietz type I (n = 1) and undefined (n = 1)].

For 10 patients with <2+ preoperative AI, internal ring annuloplasty performed for annular stabilization as part of VSRR.

AI: aortic insufficiency; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; BMI: body mass index; EF: ejection fraction; IQR: interquartile range; NYHA: New York Heart Association; TIA: transient ischaemic attack; VSRR: valve-sparing root replacement.

Patient operative characteristics are presented in Table 2. The median baseline aortic annular diameter was 27 mm (IQR 25–28) and 27 mm (IQR 25–29) for trileaflet and bicuspid patients, respectively. The median ring size was 21 mm (IQR 21–23) for trileaflet patients and 21 mm (IQR 20–23) for bicuspid patients. Cusp plication was required in 22% undergoing trileaflet repair and 100% undergoing bicuspid repair. Proximal aortic procedures performed in addition to AVr included supracoronary ascending replacement in 26 (55%) patients and remodelling VSRR with or without selective sinus replacement in 20 (43%) patients. The number of sinuses replaced was 1 in 13, 2 in 3 and 3 (all connective tissue disorder patients) in 4. One patient underwent resection of a subaortic membrane in conjunction with valve repair. Concomitant arch replacement was performed in 38 (81%) patients, including hemi-arch in 34 patients and total arch in 4 patients. There was no 30-day/in-hospital mortality. Three patients experienced postoperative stroke. One patient with chronic kidney disease experienced new dialysis. One patient required permanent pacemaker. Forty-one (87%) patients had zero or trace AI on immediate post-repair transoesophageal echocardiography and 6 patients had 1+ AI. The median early post-repair mean gradient was 18 mmHg (IQR 4–21) and 7 mmHg (IQR 6–12) in trileaflet and bicuspid patients, respectively.

Table 2:

Procedural characteristics and 30-day/in-hospital outcomes stratified by native aortic valve morphology

| Variables | Total (n = 47) | Trileaflet aortic valve (n = 36) | Bicuspid aortic valve (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Redo sternotomy, % (n) | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Median CPB time (min) (IQR) | 159 (142–191) | 156 (140–200) | 161 (154–177) |

| Median aortic cross-clamp time (min) (IQR) | 128 (114–148) | 126 (112–153) | 131 (127–144) |

| Annuloplasty ring type, % (n) | |||

| HAART 200 | 23 (11) | 0 (0) | 100 (11) |

| HAART 300 | 77 (36) | 100 (36) | 0 (0) |

| Median ring size (mm) (IQR) | 21 (20–23) | 21 (21–23) | 21 (20–23) |

| Root repair, % (n) | |||

| Yacoub (full) | 9 (4) | 11 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Selective sinus replacement Yacoub | 34 (16) | 36 (13) | 27 (3) |

| Selective sinus replacement, % (n) | |||

| Non | 21 (10) | 19 (7) | 27 (3) |

| Right | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Non, right | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Cusp plication, % (n) | 40 (19) | 22 (8) | 100 (11) |

| Supracoronary ascending repair, % (n) | 55 (26) | 50 (18) | 73 (8) |

| Concomitant arch repair, % (n) | |||

| Total arch | 9 (4) | 13 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Hemi-arch | 72 (34) | 64 (23) | 100 (11) |

| Early postoperative AI grade on TEE, % (n) | |||

| None/trace | 87 (41) | 83 (30) | 100 (11) |

| 1+ | 13 (6) | 17 (6) | 0 (0) |

| ≥2+ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Median early postoperative mean AV gradient on TEE (mmHg) (IQR) | 13 (5–20) | 18 (4–21) | 7 (6–12) |

| Median postoperative days in ICU (IQR) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) |

| Median postoperative length of stay (days) (IQR) | 5 (4–7) | 5 (4–7) | 4 (4–5) |

| Postoperative stroke, % (n) | 6 (3) | 8 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative prolonged ventilation (>24 h), % (n) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Postoperative new dialysis, % (n) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| New permanent pacemaker placement, % (n) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| In-hospital/30-day mortality, % (n) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

AI: aortic insufficiency; AV: aortic valve; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; TEE: transoesophageal echocardiography.

Clinical follow-up was 100% complete (Table 3). Late follow-up imaging was available in 32 (68%) patients at a median of 11 months (IQR 10–13) postsurgery. AI was zero–trace in 47% with 1+ AI in 50% and 2+ AI in 3% (Fig. 5). For those patients with ≥2+ preoperative AI with follow-up imaging available (n = 23), AI was ≤1+ in 96% (n = 22). For those patients with <2+ AI in whom the ring was placed for annular stabilization as part of a VSRR procedure with follow-up imaging available (n = 8), none had AI >1+. Eighty-one percent (n = 38) of patients were NYHA class I at follow-up, and the median follow-up mean AV gradient was 11 mmHg (IQR 8–14). All patients were alive and free from aortic valve reintervention at last follow-up.

Table 3:

Follow-up data stratified by native aortic valve morphology

| Variables | Total (n = 47) | Trileaflet aortic valve (n = 36) | Bicuspid aortic valve (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up duration (months) (IQR) | 11 (4–13) | 11 (6–13) | 5 (3–11) |

| Reoperation for aortic valve dysfunction, % (n) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| NYHA class on most recent follow-up, % (n) | |||

| I | 80 (36) | 76 (26) | 91 (10) |

| II | 20 (9) | 24 (8) | 9 (1) |

| III and IV | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Median duration from surgery until most recent imaging, if available (months) (IQR) | 11 (10–13) | 11 (10–13) | 10 (2–11) |

| Follow-up AI grade,a % (n) | |||

| Late imaging not yet performed | 32 (15) | 28 (10) | 45 (5) |

| Zero–trace | 32 (15) | 28 (10) | 45 (5) |

| 1+ | 34 (16) | 42 (15) | 9 (1) |

| 2+ | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Median follow-up mean AV gradient (mmHg) (IQR)a | 11 (8–14) | 10 (7–14) | 12 (12–13) |

Echocardiography or cardiac MRI.

AI: aortic insufficiency; AV: aortic valve; IQR: interquartile range; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; NYHA: New York Heart Association.

Figure 5:

Mean ± standard error of the mean aortic insufficiency (A), New York Heart Association (NYHA) (B) and aortic valve gradient (C) data over the study period for patients with follow-up data available (aortic insufficiency: n = 32; NYHA: n = 45; gradient: n = 24).

DISCUSSION

The current study reports the early, ‘real-world’, post-FDA approval experience for rigid internal geometric aortic ring annuloplasty in 47 patients, including both TAV and BAV, undergoing PAR. The addition of ring annuloplasty to PAR appeared safe with no perioperative mortality and no late annuloplasty-related complications at early median postoperative follow-up of 11 months. The median aortic cross-clamp time was 128 min and slightly longer in patients with BAV, consistent with the more complex repairs required in this population. Patients with preoperative AI ≥2+ experienced resolution of AI with AI grade ≤1+ in 96%. The only patient with late 2+ AI had Marfan syndrome with a 31-mm annulus, centrally thickened nodules of Aranti, multiple stress fenestrations, and multicusp prolapse requiring multiple cusp plications, and in retrospect likely should have undergone valve replacement rather than repair. Late transvalvular gradients were low with a median of 10–12 mmHg, and no patients required late AV-related reintervention. Given these early findings, the HAART geometric ring annuloplasty would appear to be a safe and effective adjunct to PAR. This would appear especially true given that aortic root disease is a more common cause of AI than primary valve disease in the modern era [11].

The early US results presented herein largely mirror those of prior studies examining the use of the HAART geometric rigid internal annuloplasty ring in clinical trials from Europe. Mazzitelli et al. [8] reported a 4-centre pilot trial of the HAART ring in 16 patients with BAV in 2015, encountering no early valve-related complications and postrepair mean systolic gradient of 11 mmHg 6 months following surgery. The largest series to date reported outcomes of 65 patients undergoing geometric ring annuloplasty for trileaflet AI [9]. At a mean follow-up of 2 years, the authors described a mean gradient of 9 mmHg and a 10.8% rate of late AVR, which was attributed mostly to technical complications including leaflet tears from long annular suture tails or untying of post sutures. Similarly, in a trial of 16 patients with BAV, the same group reported no residual AI after surgery; however, 2 patients required AVR within months of index surgery due to leaflet tears from suture tails [6]. Given the lack of observed leaflet complications in the current cohort, it would appear that the modified ‘lateral suture fixation technique’ [6], which directs the knot towers laterally away from leaflet contact, has corrected these early problems with suture-induced cusp injury.

Mazzitelli et al. [7] also reported the first results of ring annuloplasty in 6 patients with moderate–severe AI and root aneurysms. Annuloplasty was performed as part of a root remodelling operation, similar to the technique utilized in the current report, including leaflet reconstruction and complete replacement of the sinuses with a Valsalva graft. In that study, all patients had ≤1+ AI postsurgery, with a mean gradient of 13 mmHg. More recently, a multicentre trial from Europe with a patient population similar to the current report examined mid-term outcomes for internal geometric ring annuloplasty for the repair of trileaflet and bicuspid AI in patients undergoing concomitant PAR for ascending and/or aortic root aneurysms [12]. That study enrolled 47 patients (15% BAV), of whom 87% had ≥2+ AI, and found 94% freedom from valve-related complications or AVR at 2 years.

Given the favourable results to date, we are increasingly using geometric ring annuloplasty as part of PAR at our institution for patients with either ≥2+ AI or need for annular stabilization with VSRR due to several key benefits: (i) the ring allows recapitulation of AV geometry (elliptical for TAV and symmetric 50/50% circular for BAV) with durable annular downsizing, which promotes cusp coaptation by recruiting leaflets to the midline. This differs from reimplantation (David) VSRR-based techniques, which create a circular annulus with less rigid annular fixation; (ii) restoration of annular geometry by rigid ring annuloplasty more easily enables subsequent leaflet manipulations such as leaflet shaving and plication due to the aforementioned central leaflet recruitment; (iii) ring annuloplasty offers a standardized approach to decreasing annular diameter and restoring annular shape, which should promote wider adoption by surgeons. This lack of standardization for AVr techniques is frequently quoted as the major barrier against wider use of AVr for AI [22]; (iv) geometric ring annuloplasty facilitates selective sinus replacement since the rigid ring stabilizes the annulus, unlike the more widely utilized David reimplantation approaches to annular stabilization for AVr [22]. This shortens operative times and avoids the known risks of coronary button reimplantation in some patients [29, 30]. This is especially true given the known frequency of pathological involvement of only 1 or 2 coronary sinuses [27, 28], a finding which is especially common in the BAV aortopathy population [28]; and finally, (v) geometric ring annuloplasty still preserves the advantages of AVr over replacement and avoids prosthesis and anticoagulation-related complications associated with the latter.

Limitations

The current study has several limitations. As a retrospective analysis, the study is limited by selection bias and lack of control group undergoing AVR, suture or external ring annuloplasty or reimplantation VSRR; as such, we cannot understand the comparative effectiveness of these approaches. Furthermore, the data are limited to patients undergoing ring annuloplasty with concomitant PAR for largely chronic aortic disease; as a result, the findings cannot be generalized to patients undergoing isolated aortic valve procedures or surgery for acute AI, although 2 patients in the series underwent rigid ring annuloplasty as part of repair of subacute type A dissection. The study is also limited by small cohort size, which may minimize or mask complications that might be found in a larger experience, as well as the fact that only 68% of patients have reached the 1-year postoperative mark at which we typically obtain follow-up imaging. However, the current findings largely mirror those of prior clinical trials, suggesting external validity. Given the short time since FDA approval, the study only reports early outcomes of internal ring annuloplasty and longer-term data are needed to delineate the late failure rate and other potential late complications of the procedure. As such, the current study should be viewed as a descriptive analysis of early postapproval experience using geometric ring annuloplasty for AVr in conjunction with PAR in a single referral academic centre in the USA.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, early results with a newly FDA-approved geometric rigid annuloplasty ring for AVr in patients undergoing PAR appear promising, similar to prior clinical trial results. The device allows a standardized approach to AVr with stable annular diameter reduction and facilitates cusp plication when needed. Longer-term follow-up and additional prospective data will be required to ensure the safety and durability of the procedure and firmly establish rigid internal ring annuloplasty as an integral part of the surgeon’s armamentarium for AVr.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [5T32HL069749 to O.K.J. and FT32CA093245 to V.R.].

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Author contributions

Oliver Kayden Jawitz: Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Software; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Vignesh Raman: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Jatin Anand: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Muath Bishawi: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Soraya L. Voigt: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Julie Doberne: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Andrew M. Vekstein: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. E. Hope Weissler: Data curation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. Joseph W. Turek: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Supervision; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing. G. Chad Hughes: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Writing—original draft; Writing—review & editing.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AI

Aortic insufficiency

- AVR

Aortic valve replacement

- BAV

Bicuspid aortic valve

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IQR

Interquartile range

- PAR

Proximal aortic repair

- TAV

Trileaflet aortic valve

- VSRR

Valve-sparing root replacement

Presented at the 33rd Annual Meeting of the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Lisbon, Portugal, 3–5 October 2019.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hammermeister K, Sethi GK, Henderson WG, Grover FL, Oprian C, Rahimtoola SH.. Outcomes 15 years after valve replacement with a mechanical versus a bioprosthetic valve: final report of the Veterans Affairs randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:1152–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boodhwani M, de Kerchove L, Glineur D, Poncelet A, Rubay J, Astarci P. et al. Repair-oriented classification of aortic insufficiency: impact on surgical techniques and clinical outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cosgrove DM, Rosenkranz ER, Hendren WG, Bartlett JC, Stewart WJ.. Valvuloplasty for aortic insufficiency. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;102:571–6; discussion 6–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aicher D, Fries R, Rodionycheva S, Schmidt K, Langer F, Schafers HJ.. Aortic valve repair leads to a low incidence of valve-related complications. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rankin JS, Beavan LA, Cohn WE.. Technique for aortic valve annuloplasty using an intra-annular “hemispherical” frame. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;142:933–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mazzitelli D, Pfeiffer S, Rankin JS, Fischlein T, Choi YH, Wahlers T. et al. A regulated trial of bicuspid aortic valve repair supported by geometric ring annuloplasty. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:2010–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mazzitelli D, Nobauer C, Rankin JS, Badiu CC, Dorfmeister M, Crooke PS. et al. Early results of a novel technique for ring-reinforced aortic valve and root restoration. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazzitelli D, Stamm C, Rankin JS, Nobauer C, Pirk J, Meuris B. et al. Hemodynamic outcomes of geometric ring annuloplasty for aortic valve repair: a 4-center pilot trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazzitelli D, Fischlein T, Rankin JS, Choi YH, Stamm C, Pfeiffer S. et al. Geometric ring annuloplasty as an adjunct to aortic valve repair: clinical investigation of the HAART 300 device. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;49:987–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mazzitelli D, Nobauer C, Rankin JS, Badiu CC, Krane M, Crooke PS. et al. Early results after implantation of a new geometric annuloplasty ring for aortic valve repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:94–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Roberts WC, Ko JM, Moore TR, Jones WH 3rd. Causes of pure aortic regurgitation in patients having isolated aortic valve replacement at a single US tertiary hospital (1993 to 2005). Circulation 2006;114:422–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rankin JS, Mazzitelli D, Fischlein T, Choi YH, Pirk J, Pfeiffer S. et al. Geometric ring annuloplasty for aortic valve repair during aortic aneurysm surgery: two-year clinical trial results. Innovations 2018;13:248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ganapathi AM, Englum BR, Hanna JM, Schechter MA, Gaca JG, Hurwitz LM. et al. Frailty and risk in proximal aortic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;147:186–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Adult Cardiac Surgery Database Data Collection. 2019. https://www.sts.org/registries-research-center/sts-national-database/adult-cardiac-surgery-database/data-collection (15 March 2019, date last accessed).

- 15. Iribarne A, Keenan J, Benrashid E, Wang H, Meza JM, Ganapathi A. et al. Imaging surveillance after proximal aortic operations: is it necessary? Ann Thorac Surg 2017;103:734–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lima B, Williams JB, Bhattacharya SD, Shah AA, Andersen N, Wang A. et al. Individualized thoracic aortic replacement for the aortopathy of biscuspid aortic valve disease. J Heart Valve Dis 2011;20:387–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ganapathi AM, Hanna JM, Schechter MA, Englum BR, Castleberry AW, Gaca JG. et al. Antegrade versus retrograde cerebral perfusion for hemiarch replacement with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest: does it matter? A propensity-matched analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:2896–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Keenan JE, Wang H, Gulack BC, Ganapathi AM, Andersen ND, Englum BR. et al. Does moderate hypothermia really carry less bleeding risk than deep hypothermia for circulatory arrest? A propensity-matched comparison in hemiarch replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;152:1559–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keenan JE, Wang H, Ganapathi AM, Englum BR, Kale E, Mathew JP. et al. Electroencephalography during hemiarch replacement with moderate hypothermic circulatory arrest. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:631–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ranney DN, Yerokun BA, Benrashid E, Bishawi M, Williams A, McCann RL. et al. Outcomes of planned two-stage hybrid aortic repair with dacron-replaced proximal landing zone. Ann Thorac Surg 2018;106:1136–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD. et al. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2008;118:e523–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Al-Atassi T, Boodhwani M.. Aortic valve insufficiency in aortic root aneurysms: consider every valve for repair. J Vis Surg 2018;4:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Malas T, Saczkowski R, Sohmer B, Ruel M, Mesana T, de Kerchove L. et al. Is aortic valve repair reproducible? Analysis of the learning curve for aortic valve repair. Can J Cardiol 2015;31:1497.e15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. de Kerchove L, Mastrobuoni S, Froede L, Tamer S, Boodhwani M, van Dyck M. et al. Variability of repairable bicuspid aortic valve phenotypes: towards an anatomical and repair-oriented classification. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019; doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezz033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mazzitelli D, Stamm C, Rankin JS, Pfeiffer S, Fischlein T, Pirk J. et al. Leaflet reconstructive techniques for aortic valve repair. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:2053–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schafers HJ, Aicher D, Langer F, Lausberg HF.. Preservation of the bicuspid aortic valve. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:S740–5; discussion S85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Urbanski PP, Jankulowski A, Morka A, Irimie V, Zhan X, Zacher M. et al. Patient-tailored aortic root repair in adult marfanoid patients: surgical considerations and outcomes. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:43–51.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ugur M, Schaff HV, Suri RM, Dearani JA, Joyce LD, Greason KL. et al. Late outcome of noncoronary sinus replacement in patients with bicuspid aortic valves and aortopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:1242–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kincaid EH, Cordell AR, Hammon JW, Adair SM, Kon ND.. Coronary insufficiency after stentless aortic root replacement: risk factors and solutions. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:964–8; discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patel MD, Hyde J.. Percutaneous management of coronary button kinking after emergency aortic root replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 2020;109:e1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]