Just a few weeks ago, more than half of the world's population was on lockdown to limit the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Scientists are racing against time to provide a proven treatment. Beyond the current outbreak, in the longer term, the development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and their global access are a priority to end the pandemic.1 However, the success of this strategy relies on people's acceptability of immunisation: what if people do not want the shot? This question is not rhetorical; many experts have warned against a worldwide decline in public trust in immunisation and the rise of vaccine hesitancy during the past decade, especially in whole Europe and in France.2, 3 Early results from a survey done in late March in France suggests that this distrust is likely to become an issue when the vaccine will be made available.

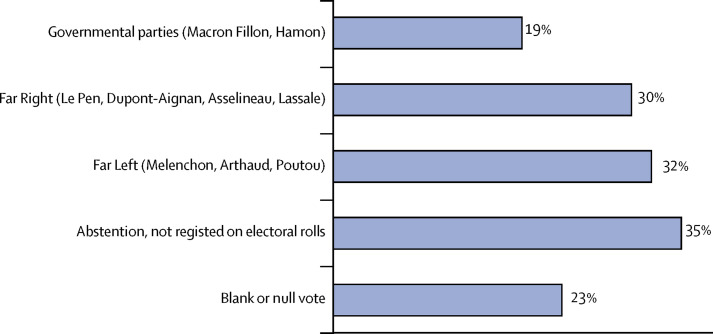

We did an online survey in a representative sample of the French population aged 18 years and older 10 days after the nationwide lockdown was introduced (March 27–29). We found that 26% of respondents stated that, if a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 becomes available, they would not use it. It might come as a surprise given the situation a few weeks ago: the whole population was confined as the outbreak had not yet reached its peak, and media were flooded with daily death tolls and the saturation of intensive care wards. The social profile of reluctant responders is even more worrying: this attitude was more prevalent among low-income people (37%), who are generally more exposed to infectious diseases,4 among young women (aged 18–35 years; 36%), who play a crucial role regarding childhood vaccination,5 and among people aged older than 75 years (22%), who are probably at an increased risk for severe illness from COVID-19. Our data also suggest that the political views of respondents play an important part in their attitude. Participants' acceptation of a vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 strongly depended on their vote at the first round of the 2017 presidential election (figure ): those who had voted for a far left or far right candidate were much more likely to state that they would refuse the vaccine, as well as those who abtained from voting.

Figure.

The French public's intention to refuse vaccination against COVID-19 according to their vote at the first round of the 2017 presidential election, March 27–29, COCONEL Survey (n=1012)

These early results are not entirely surprising. When this dimension has been studied, researchers have often found a connection between political beliefs and attitudes to vaccines.6 They highlight a crucial issue for public health interventions: how can we assure the public that recommendations reflect the state of scientific knowledge rather than political interests? This problem is exacerbated in times of crisis, during which there is considerable scientific uncertainty, available measures have a limited effect, and politicians—rather than experts—are the public face of crisis management. This is one of the lessons that can be drawn from the H1N1 influenza pandemic of 2009 in France. As the pandemic unfolded, the apparent national unity of the early phase broke apart. Criticism of the government's strategy was voiced by prominent members of nearly all of the opposition parties.7 A public debate around the safety of the vaccine arose, with prominent politicians and activists claiming that it had been produced too hastily and not been tested enough. This was crucial in the failure of the vaccination campaign (only 8% of the population was vaccinated).8 It also ushered in an era of perpetual debate over vaccination in France.9 One of the crucial mistakes made at the time by French authorities was to refuse to communicate early on the measures taken to ensure the safety of the vaccine for fear that the mere evocation of risk might provoke irrational reactions.10 This approach let critics set the agenda on this issue, condemning public authorities to a defensive position.

Public authorities are setting up fast-track approval processes for a putative vaccine against SARS-CoV-2.9 It is crucial to communicate early and transparently on these processes to avoid vaccines becoming part of political debates.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

The COCONEL Group:

Patrick Peretti-Watel, Valérie Seror, Sébastien Cortaredona, Odile Launay, Jocelyn Raude, Pierrea Verger, Lisa Fressard, François Beck, Stéphane Legleye, Olivier L'Haridon, Damien Léger, and Jeremy Keith Ward

References

- 1.Yamey G, Schäferhoff M, Hatchett R, Pate M, Zhao F, McDade KK. Ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines. Lancet. 2020;395:1405–1406. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30763-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shetty P. Experts concerned about vaccination backlash. Lancet. 2010;375:970–971. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60421-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z. The state of vaccine confidence 2016: global insights through a 67-country survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maertens de Noordhout C, Devleesschauwer B, Salomon JA. Disability weights for infectious diseases in four European countries: comparison between countries and across respondent characteristics. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28:124–133. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckx090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peretti-Watel P, Ward JK, Vergelys C, Bocquier A, Raude J, Verger P. ‘I think I made the right decision … I hope I'm not wrong’. Vaccine hesitancy, commitment and trust among parents of young children. Sociol Health Illn. 2019;41:1192–1206. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy J. Populist politics and vaccine hesitancy in Western Europe: an analysis of national-level data. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29:512–516. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward JK. Rethinking the antivaccine movement concept: a case study of public criticism of the swine flu vaccine's safety in France. Soc Sci Med. 2016;159:48–57. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raude J, Caille-Brillet A-L, Setbon M. The 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza vaccination in France: who accepted to receive the vaccine and why? PLoS Curr. 2010;2 doi: 10.1371/currents.RRN1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ward JK, Peretti-Watel P, Bocquier A, Seror V, Verger P. Vaccine hesitancy and coercion: all eyes on France. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:1257–1259. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0488-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ward JK. Les publics de l'action publique: gouvernement et résistances. Presses du Septentrion; Villeneuve-d'Ascq: 2016. Informer sans inquiéter: rationalité et irrationalité du public dans la communication sur la grippe A. [Google Scholar]